16

Dr. Andreas Petzold; Valerie Spanswick; Christine M. Bolli; Dr. Elisa Foster; Dr. Shannon Pritchard; and Dr. Diane Reilly

In this chapter

A beginner’s guide to Romanesque art

The first international style since antiquity

The term “Romanesque,” meaning in the manner of the Romans, was first coined in the early nineteenth century. Today it is used to refer to the period of European art from the second half of the eleventh century throughout the twelfth (with the exception of the region around Paris where the Gothic style emerged in the mid-twelfth century). In certain regions, such as central Italy, the Romanesque continued to survive into the thirteenth century. The Romanesque is the first international style in Western Europe since antiquity—extending across the Mediterranean and as far north as Scandinavia. The transmission of ideas was facilitated by increased travel along the pilgrimage routes to shrines such as Santiago de Compostela in Spain (a pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place) or as a consequence of the crusades which passed through the territories of the Byzantine empire. There are, however, distinctive regional variants—Tuscan Romanesque art (in Italy) for example is very different from that produced in northern Europe.

Painting + sculpture + architecture

The relation of art to architecture—especially church architecture—is fundamental in this period. For example, wall-paintings may follow the curvature of the apse of a church as in the apse wall-painting from the church of San Clemente in Taüll, and the most important art form to emerge at this period was architectural sculpture—with sculpture used to decorate churches built of stone.

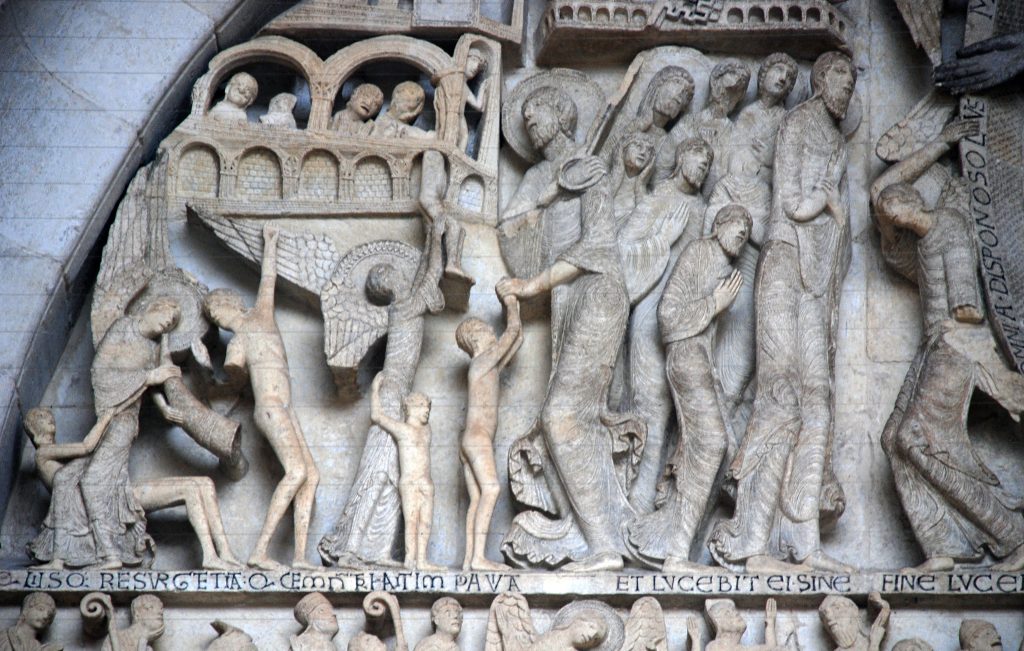

Many sculptors may have begun their career as stone masons, and there is a remarkable coherence between architecture and sculpture in churches at this period. The two most important sculptural forms to emerge at this time were the tympanum (the lunette-shaped space above the entrance to a church), and the historiated capital (a capital incorporating a narrative element usually an episode from the Bible or the life of a saint). One of the most famous tympanums is on the west entrance to Autun Cathedral (below) which represents—appropriately for this part of the church—the Last Judgment. An inscription (Gislebertus hoc fecit” “Gislebertus made me”), at the base of the giant immobile figure of Christ at the center, records the name of the artist or head of the workshop which produced it, though it has been suggested that it may refer to the original patron who was responsible for bringing the relics of Lazurus to Autun in the Carolingian period.

The influence of ancient Rome

One influence on the Romanesque is, as the name implies, ancient Roman art—especially sculpture—which survived in large quantities particularly in southern Europe. This can be seen, for example, in a marble relief representing the calling of St. Peter and St. Andrew from the front frieze of the abbey church of Sant Pere de Rodes on the Catalonian coast. The imprint of the antique can be seen in the deep undercutting in the drapery folds, an effect achieved by the Roman device of the drill, and the individualization of the faces.

Classical influence was also frequently mediated through an intermediary—most importantly Byzantine art (especially textiles and painting), but also through earlier medieval styles which had absorbed elements of the classical tradition such as Ottonian art.

The illustrations in the Bury Bible have, for example, been convincingly compared to Byzantine wall-paintings in a church at Asinou in Cyprus which suggests that its artist—a certain Master Hugo (having the name of the artist is unusual during this period) had seen them or a similar source. Monasteries such as that of Bury St. Edmunds in East Anglia in England (where the Bury Bible was made) were important centers of production—especially for the writing and decorating of manuscripts. The Bury Bible is a good example of the remarkable achievements of monastic scriptoria in the Romanesque period.

Monasteries were not the only centers of production. Romanesque art is also associated with towns that were revived and expanded during this period—for the first time since the fall of the Roman empire—a consequence of broad economic expansion (examples include Assisi in Umbria with its Romanesque cathedral or the newly founded town of Puente La Reina in northern Spain on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela).

Romanesque art is for the most part religious in its imagery, but this is partly a matter of what has survived, and there are examples of secular art from the period. Unusual is a casket in The British Museum, a product of Limoges craftsmanship, which is made of wood with champlevé enamels attached to it (produced by heating powdered glass set into groves hollowed out of bronze plate). This is decorated with scenes to do with courtly love inspired by troubadour poets from Provence.

Metalwork

The distinction between the fine and decorative arts is one that emerges only in the Renaissance and does not apply at this earlier period. If anything the most highly valued works of art during the Romanesque period were objects of metalwork made from precious metals that were frequently produced to house relics (characteristically the body part of a saint, or—in the case of Christ who, the faithful believe ascended to heaven—objects associated with him such as fragments of the so-called true cross on which Christ was thought to have been crucified).

An example of this is the reliquary known as the Stavelot Triptych. It consists of a central panel flanked by side wings that can be closed, a design format derived from Byzantine art but made at the Benedictine monastery of Stavelot in the Mosan region in present day Belgium in the mid-twelfth century. The triptych was commissioned by the abbot, a man called Wibald, whom we know travelled extensively and who acquired, during a trip to Constantinople, the two Byzantine enamel plaques incorporated into the center of the triptych that contain what were believed to be fragments of the true cross.

A wall painting from San Clemente in Catalonia

The apse wall-painting from the church of San Clemente is a good example of the Romanesque style. The church is situated in a remote valley in northern Catalonia (north-east Spain today) and is typical of the handsome stone-built churches which sprung up in this region in the Romanesque period. The painting would have been painted onto fresh plaster applied to the walls of the church (it was transferred for safekeeping to the Museum of Catalan Art in Barcelona early in the twentieth century). The painting is dominated by the giant figure of Christ in a mandorla (a halo around the body of a sacred person), represented as he will appear at the end of time as described in the Book of Revelation.

Christ is represented characteristically out of scale to the other figures to indicate his status. His head is distorted, elongated and highly geometric, and he has piercing hypnotic eyes. To either side of him are written the Greek letters “alpha” and “omega” (the beginning and the end), and with one hand he gestures in blessing, while the other holds an open book with the words Ego sum lux mundi (I am the light of the world) inscribed on it. Below him is an equally elongated and distorted figure of the Virgin Mary who holds a chalice with Christ’s blood, a representation of the Holy Grail which predates the earliest written description of the subject. Her presence in the scheme is symptomatic of the growing cult of the Virgin Mary at this period.

It would be just as much a mistake to regard the lack of naturalism found in this painting as indicating lack of artistic competence as it would be in a work by Picasso. Rather it indicates that its artist (whose real name we do not know) is not interested in replicating external appearances but rather in conveying a sense of the sacred and communicating the religious teachings of the church. Picasso (who was brought up in Barcelona) greatly admired Catalonian Romanesque, and it is significant that later in his life he kept a poster of this painting in his studio in southern France. We live in a world saturated with images but in the Romanesque period people would rarely encounter them and an image such as this would have made an immense impression.

A beginner’s guide to Romanesque architecture

The name gives it away–Romanesque architecture is based on Roman architectural elements. It is the rounded Roman arch that is the literal basis for structures built in this style.

Ancient Roman ruins (with arches)

All through the regions that were part of the ancient Roman Empire are ruins of Roman aqueducts and buildings, most of them exhibiting arches as part of the architecture (you may make the etymological leap that the two words—arch and architecture—are related, but the Oxford English Dictionary shows arch as coming from Latin arcus, which defines the shape, while arch—as in architect, archbishop and archenemy—comes from Greek arkhos, meaning chief and ekton means builder).

When Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 C.E., Europe began to take its first steps out of the “Dark Ages” since the fall of Rome in the fifth century. The remains of Roman civilization were seen all over the continent, and legends of the great empire would have been passed down through generations. So when Charlemagne wanted to unite his empire and validate his reign, he began building churches in the Roman style–particularly the style of Christian Rome in the days of Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor.

After a gap of around two hundred years with no large building projects, the architects of Charlemagne’s day looked to the arched, or arcaded, system seen in Christian Roman edifices as a model. It is a logical system of stresses and buttressing, which was fairly easily engineered for large structures, and it began to be used in gatehouses, chapels, and churches in Europe.

These early examples may be referred to as pre-Romanesque because, after a brief spurt of growth, the development of architecture again lapsed. As a body of knowledge was eventually re-developed, buildings became larger and more imposing. Examples of Romanesque cathedrals from the early Middle Ages (roughly 1000-1200) are solid, massive, impressive churches that are often still the largest structure in many towns.

In Britain, the Romanesque style became known as “Norman” because the major building scheme in the 11th and 12th centuries was instigated by William the Conqueror, who invaded Britain in 1066 from Normandy in northern France. (The Normans were the descendants of Vikings—Norse, or north men—who had invaded this area over a century earlier.) Durham and Gloucester Cathedrals and Southwell Minster are excellent examples of churches in the Norman, or Romanesque style.

The arches that define the naves of these churches are well modulated and geometrically logical—with one look you can see the repeating shapes, and proportions that make sense for an immense and weighty structure. There is a large arcade on the ground level made up of bulky piers or columns. The piers may have been filled with rubble rather than being solid, carved stone. Above this arcade is a second level of smaller arches, often in pairs with a column between the two. The next higher level was again proportionately smaller, creating a rational diminution of structural elements as the mass of the building is reduced.

The decoration is often quite simple, using geometric shapes rather than floral or curvilinear patterns. Common shapes used include diapers—squares or lozenges—and chevrons, which were zigzag patterns and shapes. Plain circles were also used, which echoed the half-circle shape of the ubiquitous arches.

Early Romanesque ceilings and roofs were often made of wood, as if the architects had not quite understood how to span the two sides of the building using stone, which created outward thrust and stresses on the side walls. This development, of course, didn’t take long to manifest, and led from barrel vaulting (simple, semicircular roof vaults) to cross vaulting, which became ever more adventurous and ornate in the Gothic.

Pilgrimage routes and the cult of the relic

The end of the world

Y2K. The Rapture. 2012. For over a decade, speculation about the end of the world has run rampant—all in conjunction with the arrival of the new millennium. The same was true for our religious European counterparts who, prior to the year 1000, believed the Second Coming of Christ was imminent, and the end was nigh.

When the apocalypse failed to materialize in 1000, it was decided that the correct year must be 1033, a thousand years from the death of Jesus Christ, but then that year also passed without any cataclysmic event.

Just how extreme the millennial panic was, remains debated. It is certain that from the year 950 onwards, there was a significant increase in building activity, particularly of religious structures. There were many reasons for this construction boom beside millennial panic, and the building of monumental religious structures continued even as fears of the immediate end of time faded.

Not surprisingly, this period also witnessed a surge in the popularity of the religious pilgrimage. A pilgrimage is a journey to a sacred place. These are acts of piety and may have been undertaken in gratitude for the fact that doomsday had not arrived, and to ensure salvation, whenever the end did come.

The pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela

For the average European in the 12th Century, a pilgrimage to the Holy Land of Jerusalem was out of the question—travel to the Middle East was too far, too dangerous and too expensive. Santiago de Compostela in Spain offered a much more convenient option.

To this day, hundreds of thousands of faithful travel the “Way of Saint James” to the Spanish city of Santiago de Compostela. They go on foot across Europe to a holy shrine where bones, believed to belong to Saint James, were unearthed. The Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela now stands on this site.

The pious of the Middle Ages wanted to pay homage to holy relics, and pilgrimage churches sprang up along the route to Spain. Pilgrims commonly walked barefoot and wore a scalloped shell, the symbol of Saint James (the shell’s grooves symbolize the many roads of the pilgrimage).

In France alone there were four main routes toward Spain. Le Puy, Arles, Paris and Vézelay are the cities on these roads and each contains a church that was an important pilgrimage site in its own right.

Why make a pilgrimage?

A pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela was an expression of Christian devotion and it was believed that it could purify the soul and perhaps even produce miraculous healing benefits. A criminal could travel the “Way of Saint James” as an act penance. For the everyday person, a pilgrimage was also one of the only opportunities to travel and see some of the world. It was a chance to meet people, perhaps even those outside one’s own class. The purpose of pilgrimage may not have been entirely devotional.

The cult of the relic

Pilgrimage churches can be seen in part as popular desinations, a spiritual tourism of sorts for medieval travelers. Guidebooks, badges and various souvenirs were sold. Pilgrims, though traveling light, would spend money in the towns that possessed important sacred relics.

The cult of relic was at its peak during the Romanesque period (c. 1000 – 1200). Relics are religious objects generally connected to a saint, or some other venerated person. A relic might be a body part, a saint’s finger, a cloth worn by the Virgin Mary, or a piece of the True Cross.

Relics are often housed in a protective container called a reliquary. Reliquarys are often quite opulent and can be encrusted with precious metals and gemstones given by the faithful. An example is the Reliquary of Saint Foy, located at Conques abbey on the pilgrimage route. It is said to hold a piece of the child martyr’s skull. A large pilgrimage church might be home to one major relic, and dozens of lesser-known relics. Because of their sacred and economic value, every church wanted an important relic and a black market boomed with fake and stolen goods.

Accommodating crowds

Pilgrimage churches were constructed with some special features to make them particularly accessible to visitors. The goal was to get large numbers of people to the relics and out again without disturbing the Mass in the center of the church. A large portal that could accommodate the pious throngs was a prerequisite. Generally, these portals would also have an elaborate sculptural program, often portraying the Second Coming—a good way to remind the weary pilgrim why they made the trip!

A pilgrimage church generally consisted of a double aisle on either side of the nave (the wide hall that runs down the center of a church). In this way, the visitor could move easily around the outer edges of the church until reaching the smaller apsidioles or radiating chapels. These are small rooms generally located off the back of the church behind the altar where relics were often displayed. The faithful would move from chapel to chapel venerating each relic in turn.

Thick walls, small windows

Romanesque churches were dark. This was in large part because of the use of stone barrel-vault construction. This system provided excellent acoustics and reduced fire danger. However, a barrel vault exerts continuous lateral (outward pressure) all along the walls that support the vault.

This meant the outer walls of the church had to be extra thick. It also meant that windows had to be small and few. When builders dared to pierce walls with additional or larger windows they risked structural failure. Churches did collapse.

Later, the masons of the Gothic period replaced the barrel vault with the groin vault which carries weight down to its four corners, concentrating the pressure of the vaulting, and allowing for much larger windows.

Church and Reliquary of Sainte-Foy, France

On the road

Imagine you pack up your belongings in a sack, tie on your cloak, and start off on a months-long journey through treacherous mountains, unpredictable weather and unknown lands. For the medieval pilgrim, life was a spiritual journey. Why did people in the Middle Ages take pilgrimages? There are many reasons, but visiting a holy site meant being closer to God. And if you were closer to God in this life, you would also be closer to God in the next.

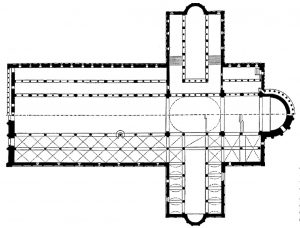

A Romanesque pilgrimage church: Saint-Foy, Conques

Located in Conques, the Church of Saint-Foy (Saint Faith) is an important pilgrimage church on the route to Santiago de Compostela in Northern Spain. It is also an abbey, meaning that the church was part of a monastery where monks lived, prayed and worked. Only small parts of the monastery have survived but the church remains largely intact. Although smaller churches stood on the site from the seventh century, the Church of Saint-Foy was begun in the eleventh century and completed in the mid-twelfth century. As a Romanesque church, it has a barrel-vaulted nave lined with arches on the interior.

It is known as a pilgrimage church because many of the large churches along the route to Santiago de Compostela took a similar shape. The main feature of these churches was the cruciform plan. Not only did this plan take the symbolic form of the cross but it also helped control the crowds of pilgrims. In most cases, pilgrims could enter the western portal and then circulate around the church towards the apse at the eastern end. The apse usually contained smaller chapels, known as radiating chapels, where pilgrims could visit saint’s shrines, especially the sanctuary of Saint Foy. They could then circulate around the ambulatory and out the transept, or crossing. This design helped to regulate the flow of traffic throughout the church although the intention and effective use of this design has been debated.

A warning in stone: The tympanum of the Last Judgment

When a pilgrim arrived at Conques, they would probably head for the church to receive blessing. Yet before they got inside, an important message awaited them on the portals: the Last Judgment. This scene is depicted on the tympanum, the central semi-circular relief carving above the central portal.

In the center sits Christ as Judge, and he means business! He sits enthroned with his right hand pointing upwards to the saved while his left hand gestures down to the damned. This scene would have served as a reminder to those entering the Church of Saint-Foy about the joys of heaven and torments of hell. Immediately on Christ’s right are Mary, Peter and possibly the founder of the monastery as well as an entourage of other saints.

Below these saints, a small arcade is covered by a pediment, meant to represent the House of Paradise. These are the blessed, those have been saved by Christ and who will remain in Paradise with him for eternity. At the center, we find Abraham and above him notice the outstretched hand of God, who beckons a kneeling Saint Faith (see image below).

On the other side of the pediment, a row of angels opens the graves of the dead. As the dead rise from their tombs, their souls will be weighed and they will be admitted to heaven or hell. This is the scene that we see right under Christ’s feet—you can see the clear division between a large doorway leading to Paradise and a terrifying mouth that leads the way to Hell.

Inside Hell, things aren’t looking very good. It is a chaotic, disorderly scene—notice how different it looks from the right-hand side of the tympanum. There is also a small pediment in the lower register of Hell, where the Devil, just opposite to Abraham, reigns over his terrifying kingdom.

The devil, like Christ, is also an enthroned judge, determining the punishments that await the damned according to the severity of their sins. In particular, to the devil’s left is a hanged man. This man is a reference to Judas, who hanged himself after betraying Christ. Just beyond Judas, a knight is tossed into the fires of Hell and above him, a gluttonous man is hung by his legs for his sins. Each of these sinners represents a type of sin to avoid, from adultery, to arrogance, even to the misuse of church offices. Indeed, this portal was not only a warning for pilgrims, but for the clergy who lived in Conques as well.

The reliquary

Pilgrims arriving in Conques had one thing on their mind: the reliquary of Saint Foy. This reliquary, or container holding the remains of a saint or holy person, was one of the most famous in all of Europe. So famous that it was originally located in a monastery in Agen but the monks at Conques plotted to steal it in order to attract more wealth and visitors. The reliquary at Conques held the remains of Saint Foy, a young Christian convert living in Roman-occupied France during the second century. At the age of twelve, she was condemned to die for her refusal to sacrifice to pagan gods, she is therefore revered as a martyr, as someone who dies for their faith. Saint Foy was a very popular saint in Southern France and her relic was extremely important to the church; bringing pilgrims and wealth to the small, isolated town of Conques.

Although the date of the reliquary is unknown, Bernard of Angers first spoke it about in 1010. At first, Bernard was frightened that the statue was too beautiful stating, “Brother, what do you think of this idol? Would Jupiter or Mars consider himself unworthy of such a statue?” He was concerned about idolatry—that pilgrims would begin to worship the jewel-encrusted reliquary rather than what that reliquary contained and represented, the holy figure of Saint Foy. Indeed, the gold and gem encrusted statue would been quite a sight for the pilgrims. Over time, travelers paid homage to Saint Foy by donating gemstones for the reliquary so that her dress is covered with agates, amethysts, crystals, carnelians, emeralds, garnets, hematite, jade, onyx, opals, pearls, rubies, sapphires, topazes, antique cameos and intaglios. Her face, which stares boldly at the viewer, is thought to have originally been the head of a Roman statue of a child. The reuse of older materials in new forms of art is known as spolia. Using spolia was not only practical but it made the object more important by associating it with the past riches of the Roman Empire.

The Church of Saint Foy at Conques provides an excellent example of Romanesque art and architecture. Although the monastery no longer survives, the church and treasury stand as a reminder of the rituals of medieval faith, especially for pilgrims. Even today, people make the long trek to Conques to pay respect to Saint Foy. Every October, a great celebration and procession is held for Saint Foy, continuing a medieval tradition into present day devotion.

Saint-Pierre, Moissac

The church of Ste. Pierre (St. Peter) in Moissac, France, dating from 1115-30, has one of the most impressive and elaborate Romanesque portals of the twelfth century. Carved images occupy the walls of the extended porch leading to the door, the door itself, and even the space over the door.

Pilgrimage routes

The church of Ste. Pierre was on one of the pilgrimage roads through France that led to Santiago de Campostela, in Spain. As it was home to the remains of St. James Major, that Spanish church was one of the most important pilgrimage sites in Western Europe. Ste. Pierre in Moissac was a popular stop for those making the long and arduous journey to Spain.

In order to understand what is depicted on the main areas surrounding the portal that leads into the church, let’s break it down into its constituent parts. The term portal refers to a doorway or entry into a building, and Romanesque portals have distinct architectural elements which were oftentimes carved with a variety of ornament and subject matter.

In the case of Ste. Pierre, the portal is divided in half vertically by the trumeau, which is decorated on three of its four sides. On the front, the viewer is faced with three pairs of intertwined lions and lionesses who are there to symbolically guard the entry into the sacred space of the church. Such symbolism comes from Early Christian imagery where the doors to Christ’s tomb are often shown with lion’s heads on them. On the east side of the trumeau is a representation of the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah (some scholars suggest it is Isaiah), who holds a scroll in his hands. On the west side is a figure identified as St. Paul, from the New Testament.

The placement of these two figures on the sides of the trumeau was no doubt deliberate as they face two other figures on the door jambs (the outer walls of the portal where the doors are attached). Across from St. Paul is a representation of St. Peter, also a New Testament saint (and the namesake of the church), and across from Jeremiah, is the Old Testament prophet Isaiah. The pairing of Old and New Testament figures was common during this period as a means of suggesting the fulfillment of Mosaic law (the law coming Moses) in the new Christian law under Christ.

The trumeau has more than just a decorative function though as it is also supports the horizontal beam of stone above called the lintel. The lintel is decorated with ten rosettes that are bound together by a carved rope and have a repeated floral pattern at both the upper and lower spaces between each rosette. Notice that on both the left and right ends of the lintel, the rope and rosette design is coming from the mouth of a fantastical animal of some sort (image, above)! Details such as these, with imaginative, hybrid animals are a common characteristic in Romanesque art from illuminated manuscripts to sculpture.

Just above the lintel is the lunette-shaped (semi-circular) tympanum, which has the majority of the sculpted decoration (and this is true in most Romanesque and Gothic portals). In this case, the tympanum is surrounded by three decorative archivolts (arches), which have various foliate patterns carved into the individual blocks of stone, known as the voussoirs, which make them up.

During the Romanesque and Gothic periods, there were two subjects which were popular for tympanum decoration. One was the subject of the Last Judgment, when Christ sits as judge over those who will be divided into the Saved and the Damned. An example of this can be seen at Autun.

The other oft-represented subject is known as the Maiestas Domini (Christ in Majesty), and here at Moissac we are presented with a very literal depiction of a passage from the Book of Revelation (4:2–7), which reads:

And immediately I was in the Spirit, and behold a throne was set in heaven, and one sat on the throne…And round the throne were four and twenty seats; and upon the seats I saw four and twenty elders sitting, clothed in white raiment; and they had on their heads crowns of gold…And before the throne there was a sea of glass like unto a crystal; and in the midst of the throne, and round about the throne, were four beasts…And the first beast was like a lion, and the second beast like a calf, and third beast had a face as a man, and the fourth beast was like a flying eagle.

The moment described in this passage, and represented here, is not a narrative in the sense that the Last Judgment is, but it is rather a more esoteric concept of the Second Coming of Christ and the End of Time.

In the very center of the composition is the figure of Christ, seated on a throne, with his right hand raised in gesture of blessing. In his left hand he balances a book on his knee, perhaps a reference to the Book of Revelation. His circular halo is inscribed with a cross (known as a cruciform halo), and we can just make out the suggestion of a larger, almond-shaped body halo (called a mandorla after the Italian word for almond) just visible as the pointed arch behind Christ’s haloed head.

Immediately to the left and right of the seated figure of Christ are the Evangelical Beasts, three animals and one human figure, who represent the four Evangelists who wrote the New Testament Gospels. Matthew, in the upper left, is represented by the winged man, Mark just below is shown as the lion, Luke on the bottom right is seen as the ox, and John the Evangelist is represented as the eagle. The representation of the four Evangelists as a tetramorph was common in sculpture, painting, and illuminated manuscripts.

On either side of the Evangelical Beasts are two tall, elegant angels holding scrolls, as well as the twenty-four elders mentioned in the text from Revelations. They are arranged on three levels, two of which are divided by wavy lines, reminding us of the “sea of glass.” Each elder holds a small musical instrument in one hand and a chalice in the other (some of these have broken off over time). Very clearly all of the figures—man and beast—are turned toward the central figure of Christ, who stares serenely out toward the viewer. The twenty-four elders crane their necks and twist their bodies as do the Evangelical beasts. Even the lines of the drapery seem to be directing our attention toward the center.

A brief comparison between the style of the sculptures in this tympanum and that employed on the Early Gothic portal of Chartres Cathedral (above), which is also a Maiestas Domini, clearly illustrates the very lively, almost agitated sense of the figures at Moissac. At Chartres, the twenty-four elders are now the voussoirs in the archivolts and the figure of Christ, seated frontally and surrounded by the mandorla, is flanked by the four evangelical beasts. Here, however, is a sense of clarity and three-dimensionality that is markedly different from the style seen at Moissac.

And as the road weary pilgrims would have approached the portal of the church Saint-Pierre, they were met with spectacular imagery that warned against sin, and reminded them of Christ’s sacrifice and his final coming. The portal at Moissac would have been a veritable feast for the Romanesque viewer’s eyes and souls.

Last Judgment, Tympanum, Cathedral of St. Lazare, Autun (France)

by Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

In this conversation, Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris discuss the Last Judgment Tympanum, Central Portal on west facade of the Cathedral of St. Lazare in Autun, from c. 1130-46. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/PATkTJhAUhM

Dr. Zucker: The prospect of spending an eternity in Hell is terrifying even in the abstract, but to be confronted with images that depict this must have really scared the medieval mind.

Dr. Harris: We’re looking up at the doorway of the Cathedral of Autun which represents, I think, the most terrifying image of The Last Judgement, of the damned in Hell that exists in art history.

Dr. Zucker: Of course it also includes Heaven, but I think people were, probably, spending much more time looking and fearing Hell. This is a sculpture that is one of the first monumental sculptures to be made in the Medieval period. There had been, of course, monumental sculpture in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome but after the 5th Century or so, monumental sculpture really fell away and this has been part because of the economic and political chaos of the Medieval Period. It’s at this time, around 1000 or just after that things begin to stabilize.

Dr. Harris: There’s an enormous building boom of churches in Europe during this time and we begin to see monumental sculpture on the doorways of churches and inside the churches on the capitals.

Dr. Zucker: We have this magnificent new cathedral at Autun and it’s important to remember that this was because of the relics that were here.

Dr. Harris: Pilgrims were traveling all over Europe during this period to visit the relics, the parts of saints. In this case, here at Autun, the bones of St. Lazarus. Each church had relics.

Dr. Zucker: The relics were extremely important. It was believed that they could heal the sick, that could offer blessings that might even shorten one’s time in [pb_glossary id=”996″]purgatory [/pb_glossary]if you came and paid homage to them, if you prayed to them.

Dr. Harris: Often churches were refurbished or special reliquaries were made to house those relics, but in the case of Autun, this church was built specifically to house the relics of St. Lazarus. They built a whole church for their relics.

Dr. Zucker: Of course there’s the spiritual dimension, but there’s also an economic dimension; these relics were economic engines for a community because you had these pilgrims come in, they needed to stay in inns, they needed to eat, there was a real economic prosperity that surrounded important relics. That’s certainly the case here. If you think about Lazarus, the person whose bones are within the church, this is the brother of Mary who Christ brought back to life, according to the New Testament. This is about rebirth, about a kind of hope after death. Of course, that is the subject of The Last Judgement.

Dr. Harris: So we imagine the faithful looking up at this doorway reading the “sermon in stone,” as Bernard of Clairvaux said, the story of The Last Judgement, people were illiterate, this was how they learned these stories.

Dr. Zucker: The images really were text and we are meant to read them, so let’s go ahead and do exactly that.

Dr. Harris: So, we have the most obvious figure, Christ, in the center. He’s bigger than everybody else.

Dr. Zucker: This is a kind of organization, the most important figure is largest by far. He’s so flat, he’s so linear, and there’s no concern with the proportions of his body.

Dr. Harris: He’s elongated and we see lines that are carved into the stones to indicate these repeated folds of drapery.

Dr. Zucker: There’s real concern with the decorative.

Dr. Harris: He’s frontal, he’s symmetrical, he’s this divine figure who stares out in judgement.

Dr. Zucker: He stares out past us as if he’s on a plan that is completely different from ours. He sits on a throne that is the city of Heaven and you can make out the little arched windows both below his feet and as if it was actually the furniture that he sits upon. Of course that’s a literal reading and this is meant to be metaphoric. His hands and his halo and his feet break the mandorla. This almond shape that completely encloses his body and is meant to function as almost a kind of a full body halo, a representation of his divinity.

Dr. Harris: There are four angels that surround him that seem to be ushering him forward.

Dr. Zucker: They also are literally holding up the mandorla as if this divine light that surrounds Christ has weight.

Dr. Harris: And like Christ, those angels are also elongated, their bodies move and twist in these wonderful ways.

Dr. Zucker: There is this incredible expressiveness.

Dr. Harris: We read images of The Last Judgement thinking about Christ’s left and Christ’s right. On Christ’s left are the damned, going to Hell and on his right are the blessed who’ve been selected for Heaven.

Dr. Zucker: On Christ’s right, at the top, we see the Virgin Mary who’s enthroned in Heaven. There’s an angel next to her.

Dr. Harris: Blowing a trumpet to awaken the dead and to announce the coming of Christ.

Dr. Zucker: We can see the architecture of Heaven itself with some blessed souls within it. We can see angels, as well, assisting the blessed into Heaven. It’s interesting to note that souls are represented as nude figures.

Dr. Harris: One of the most famous parts of this Tympanum is the figure of St. Michael who is weighing souls, a demon seems to be trying to tip the scales in favor of those who have sinned so they can get more souls for Hell.

Dr. Zucker: It’s so interesting to think about this literal representation of the weighing of souls, that morality has gravity in some way.

Dr. Harris: Look at that figure who hides in the drapery, those curling, lovely swirls of drapery of St. Michael. That figure is so different from the figures to the right who are being pulled up by hooks, by a demon, into the fires of Hell who have realized that they’re going to spend eternity being tortured.

Dr. Zucker: It’s pretty bad.

Dr. Harris: It’s terrifying.

Dr. Zucker: I find the demons much more interesting. Their mouths are gaping open, they look just ravenous as if they’re ready to eat those souls. They’ve got claws, there’s a three headed serpent wrapping around the legs of one of the devils. There really are images of horror here.

Dr. Harris: There’s an inscription right below the figures that make this point exactly. It reads, “May this terror terrify those whom earthly error bind, for the horror of these images here in this manner truly depicts what will be.” In the Medieval mind there is no doubt this will happen and where will you be when this happens?

Dr. Zucker: And don’t look to Christ because Christ is looking past us, it’s too late. So, let’s move down then to the area that’s closest to us that speaks to this issue of which side will we be on. The tympanum itself is that lunette, it’s that half circle, but it’s supported by a long cross beam which is called a lintel. This is the moment when the dead are lifted out of their graves, are resurrected to be judged. This is kind of a line, waiting, for the judgement.

Dr. Harris: They’re literally, at this moment, emerging from their tombs.

Dr. Zucker: You can see the sarcophagi at their feet. I see an angel that is clearly helping one soul, but on either side there are two other souls who seem to desperately clutch at that angel hoping that he’ll bring them along as well. As we move to the center, things almost seem to become a little less certain. You can see two people’s purses, one with a cross, one with a scalloped shell. This would be a reference to pilgrims who had perhaps gone to Jerusalem, who had perhaps gone to Spain trying to visit important relics so that they might be among the blessed.

Dr. Harris: Right, to improve their chances of getting into Heaven.

Dr. Zucker: And if you didn’t, things would not always work out well.

Dr. Harris: And so we see exactly that. Directly below Christ we see an angel wielding a sword toward a terrified figure, who, with his eyes bulging, seems to try to move away from the angel.

Dr. Zucker: And in fact everybody who’s in front of the angel looks absolutely terrified. Look at the figure that is kneeling, clutching the sides of his head, almost as if he’s saying, “How could this be true? How can it “have come to this?”

Dr. Harris: If you continue to bring your eye toward the right we see figures who are contorted in this recognition of their fate in Hell. They bend their knees, they form angular shapes with their bodies, compressed as though they’re being crushed into Hell. It’s incredibly expressive in their bodies.

Dr. Zucker: Dramatic, absolutely, but probably nothing is more dramatic than the realization on the face of the soul who’s head is being clutched by two enormous claws—the hands, presumably, of a devil who’s being plucked up into Hell.

Dr. Harris: You can see that the sculptor carved the eyes deeply, carved the open mouth deeply so that we get a sense of his, almost, primal scream. Our historians have interpreted an inscription on the doorway which reads, “,” Gislebertus made this, as being an inscription referring

to the sculptor himself.

Dr. Zucker: That would be extremely unusual. In the modern era we associate artwork with the genius of the individual, but in the Medieval Period artists were craftsman, artists were not seen as individual geniuses. So these objects were not signed.

Dr. Harris: But it was so nice to imagine that we knew the name of the artist who did this.

Dr. Zucker: There has been some new scholarship that suggests that perhaps we have been misled and that Gislebertus is not actually the name of the artist.

Dr. Harris: The recent scholarship suggests that Gislebertus is actually the name of a Duke who was associated with bringing the bones of St. Lazarus to Autun, so in a way, legitimizing this church as the rightful place for the bones of Lazarus.

Dr. Zucker: But even if we don’t know the name of the artist, we do know the power of his work.

Dr. Harris: There’s no doubt about that

The Romanesque churches of Tuscany: San Miniato in Florence and Pisa Cathedral

Before the Italian peninsula was unified into a single nation in the nineteenth century, it was divided into numerous separate countries, papal-controlled territories, and city states with constantly shifting boundaries. Unlike regions north of the Alps, in Italy the durable old Roman roads that snaked down the length of the peninsula were preserved by mild weather and continuous use. The former Roman cities along these roads became hubs of trade. These included Florence on the Via Cassia between Rome and the old central Italian heartland, and Pisa, on the Via Aurelia between Rome and what was known as “Roman Gaul” (today France and Belgium).

Roman walls, aqueducts, monuments, and buildings dotted the landscape, and this Roman heritage profoundly impacted the appearance of the region’s churches. During the middle ages, residents of the cities of Tuscany valued their Roman past, particularly as it was associated with the origins of institutional Christianity. Although Tuscany was a duchy and controlled by the Canossa family, in reality the cities of Tuscany soon established their own governments and civic identities.

Florence and Pisa are wonderful examples of this. During the eleventh century, each city’s Roman heritage was still visible in the form of roads and bridges, walls and cemeteries, but each city also took on its own character based on the preferences of its inhabitants and the sources of their economic strength. The architecture of San Miniato in Florence and the Cathedral of Pisa visibly express both their unique regional and civic qualities, as well as links to the Roman past.

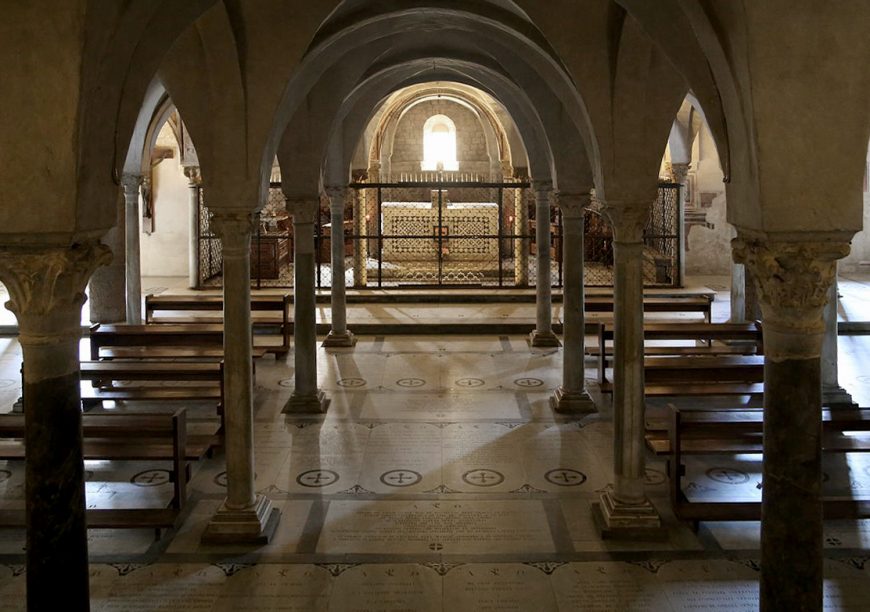

A monastery on a hill

The church of the Benedictine monastery of San Miniato al Monte (above) lies outside the early medieval walls and across the Arno from Florence. It hovers over the city on the crest of a hill, or “monte,” where Florentines believed the cell of Saint Minias, an Armenian Christian hermit who was allegedly martyred by the Roman Emperor Decius in the third century, once stood. By 1018, the bishop of Florence had ordered the construction of a church and installed a community of Benedictine monks there, following a familiar medieval pattern of locating monasteries outside, but within a short distance of, a city so that the monks could minister to the spiritual needs of the city’s inhabitants.

A synthesis of forms

The builders cleverly designed the church so that it could accommodate visitors to the tomb of Minias. Adapting a basilica-style structure with its single apse and a trussed timber roof, the builders incorporated an innovative raised chancel. Central stairways allow visitors to see and visit the crypt housing Minias’s relics, while flanking stairways lead to an elevated platform holding the altar and choir used by the monks.

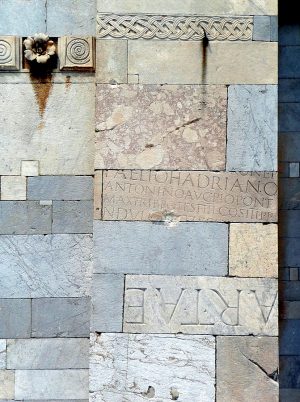

A similar synthesis of ancient, Early Christian, and medieval forms is visible in the church’s walls. An arcade of polished stone columns supporting Corinthian capitals march down the nave, above which colorful stone inlay brightens the surface—all reminiscent of Early Christian basilicas like Santa Sabina in Rome. Many of the capitals are Roman spolia, noticeable because they are much narrower than the columns they crown.

The roots of Florentine style

Yet onto this traditional framework the builders grafted imposing diaphragm arches that divide the nave into three massive bays, marked on the walls with attached columns and compound piers. The green and white stone inlay familiar from some Early Christian interiors clads the surfaces of the façade and the interior (though in some places, after money ran out, artists imitated the decorative stone in paint). This style of construction, joining modified basilican architecture with colorful, two-dimensional stone inlay, would become typical of the Florentine region.

The façade also references the Roman past. Although the component parts are flattened and rendered in pink, green and white stone, we can still identify an orderly row of columns topped by Corinthian capitals, crowned by a set of four Corinthian pilasters holding a triangular pediment that recalls a Roman temple front. In the fifteenth century, the Renaissance architect Leon Battista Alberti, would use many of the same elements in crafting the typically Tuscan façade of Santa Maria Novella, across town.

Pisa and its “Leaning Tower”

The Arno, the river that flows through Florence, eventually reaches the city of Pisa on its way to the Mediterranean Sea. In the Middle Ages, before the river’s silt deposits pushed the sea away, Pisa was located very near the coast. It was an important port city from Roman times onwards, and by the eleventh century it became a maritime republic (a city-state whose economic base was maritime trade), competing with the other Italian naval powerhouses like Genoa, Venice, and Amalfi to dominate Mediterranean trade. Pisa warred constantly with rival maritime powers in Corsica, Sicily, North Africa and on the Italian mainland. The cathedral for which it is now famous was built starting in 1063, in the wake of, and using booty from, Pisa’s naval victory over Palermo.

Like most cathedrals on the Italian peninsula, Pisa’s was built as an assemblage of freestanding buildings, including a baptistery and bell tower (campanile) in addition to the church. The Pisa cathedral complex was unusual, however, in that it was situated well outside the city walls in a grassy precinct that incorporated an ancient cemetery. Surrounded by the marshes of the Arno, the precinct’s damp soil contributed to unstable ground under the complex’s key structures, most noticeable in the campanile, which began to lean even while it was still being built in the twelfth century.

Old meets new

Pisa Cathedral, like San Miniato, borrows heavily from the architectural past. It has a basilica footprint with double aisles separated from the nave by colossal Corinthian columns, a trussed timber roof, and a single semicircular apse, all perhaps intended to recall Old St. Peter’s in Rome. Each of the arms of the transept repeats this basic formula on a smaller scale, with single aisles flanking a central space that leads to a smaller apse, creating a four-armed ground plan. This and the substantial galleries below clerestory windows recall the basilicas of the early Byzantine east.

The builders also added new features. Above the arcade and galleries and between the clerestory windows one finds expanses of cream and green striped wall. Although the pattern here is different from that found on the walls of San Miniato in Florence, both share the same complexity and conspicuous display of expensive materials.

An unusual dome

Although they probably originally planned a simpler wooden covering for the crossing, by the end of the eleventh century the builders had begun to construct a dome, perhaps to keep pace with contemporary domes built north of Tuscany in Lombardy, or even by Pisa’s economic rival, Venice. The unusual and complicated elliptical shape was dictated by the rectangular outline of the crossing created by the meeting of the nave, choir and transepts. The builders bridged the corners of this opening under the dome’s base with Byzantine-inspired squinches that resemble those built at Hosios Loukas in Greece just a few years before. Above the squinches, subtlely incised blind arcades can be seen. The colorful fresco depicting the Assumption of the Virgin was added in the 17th century.

A virtual Holy Land

Most impressive to medieval visitors would have been the exterior. The simple geometry of the façade immediately recalls San Miniato’s stack of rectangles and triangles, all resting on a shallow arcade with Corinthian capitals that frame three doors. At Pisa, though, above the ground floor, the façade becomes dramatically three-dimensional, with open arcades that screen a wall decorated with grey and white stripes.

On the church’s sides, transept, and apse, the grey and white stone has been embellished with blind arcades and colonnades (rows of columns). Lozenges, roundels, and rectangles of multicolored stone inlay dot the exterior.

Reused stones covered with inscriptions and sarcophagi imported from Rome are inserted seemingly at random: a testimony to the builders’ desire to invent an ancient heritage for the building and demonstrate the wealth and power of Pisa.

The other buildings in the complex, built starting in the twelfth century after the Pisan navy participated in the First Crusade, complete this sumptuous display. The centrally-planned, domed baptistery may have been intended to imitate the church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. It and the leaning campanile are completely encased in stacked arcades, mirroring those on the cathedral. The “Camposanto,” an enclosed cemetery, was filled with earth imported from the Holy Land in the holds of Pisan ships. Pisans may have imagined this collection of buildings, with its many references to ancient Christian sites, as a virtual Holy Land, a site they were then trying to reconquer.

Each a product of its particular region, San Miniato and Pisa Cathedral speak to the ways that medieval builders sought to express their cities’ unique identities through both ancient allusions and innovative forms.

The Bayeux Tapestry

Measuring twenty inches high and almost 230 feet in length, the Bayeux Tapestry commemorates a struggle for the throne of England between William, the Duke of Normandy, and Harold, the Earl of Wessex (Normandy is a region in northern France). The year was 1066—William invaded and successfully conquered England, becoming the first Norman King of England (he was also known as William the Conqueror).

The Bayeux Tapestry consists of seventy-five scenes with Latin inscriptions (tituli) depicting the events leading up to the Norman conquest and culminating in the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The textile’s end is now missing, but it most probably showed the coronation of William as King of England.

Although it is called the Bayeux Tapestry, this commemorative work is not a true tapestry as the images are not woven into the cloth; instead, the imagery and inscriptions are embroidered using wool yarn sewed onto linen cloth.

The tapestry is sometimes viewed as a type of chronicle. However, the inclusion of episodes that do not relate to the historic events of the Norman Conquest complicate this categorization. Nevertheless, it presents a rich representation of a particular historic moment as well as providing an important visual source for eleventh-century textiles that have not survived into the twenty-first century.

The Bayeux Tapestry was probably made in Canterbury around 1070. Because the tapestry was made within a generation of the Norman defeat of the Anglo-Saxons, it is considered to be a somewhat accurate representation of events. Based on a few key pieces of evidence, art historians believe the patron was Odo, Bishop of Bayeux. Odo was the half-brother of William, Duke of Normandy. Furthermore, the tapestry favorably depicts the Normans in the events leading up to the battle of Hastings, thus presenting a Norman point of view. Most importantly, Odo appears in several scenes in the tapestry with the inscription ODO EPISCOPUS (abbreviated “EPS” in the image below), although he is only mentioned briefly in textual sources. By the late Middle Ages, the tapestry was displayed at Bayeux Cathedral, which was build by Odo and dedicated in 1077, but its size and secular subject matter suggest that it may have been intended to be a secular hanging, perhaps in Odo’s hall.

We do not know the identity of the artists who produced the tapestry. The high quality of the needlework suggests that Anglo-Saxon embroiderers produced the tapestry. At the time, Anglo-Saxon needlework was prized throughout Europe. This theory is supported by stylistic analysis of the depicted scenes, which draw from Anglo-Saxon drawing techniques. Many of the scenes are believed to have been adapted from images in manuscripts illuminated at Canterbury.

The artists skillfully organized the composition of the tapestry to lead the viewer’s eye from one scene to the next and divided the compositional space into three horizontal zones. The main events of the story are contained within the larger middle zone. The upper and lower zones contain images of animals and people, scenes from Aesop’s Fables, and scenes of husbandry and hunting. At times the images in the borders interact with and draw attention to key moments in the narrative (as in the image above of the battle).

The seventy-five episodes depicted present a continuous narrative of the events leading up to the Battle of Hastings and the battle itself. A continuous narrative presents multiple scenes of a narrative within a single frame and draws from manuscript traditions such as the scroll form. The subject matter of the tapestry, however, has more in common with ancient monumental decoration such as Trajan’s Column, which typically focused on mythic and historical references.

The embroiderers’ attention to specific details provides important sources for scenes of eleventh-century life as well as objects that no longer survive. In one scene of the Normans’ first meal after reaching the shores of England, we see dining practices. We also see examples of armor used in the period and battle preparations. To the left of the dining scene, servants prepare food over a fire and bake bread in an outdoor oven (above). Servants serve the food as the tapestry’s assumed patron, Bishop Odo, blesses the meal (below).

Immediately after dining, William and his half-brothers Odo and Robert meet for a war council. Preparations for battle flank both sides of the first meal episode. Here we see visual evidence of eleventh-century battle gear and the construction of a motte-and-bailey to protect the Normans’ position. A motte-and-bailey is a fortification with a keep (tower) situated on a raised earthwork (motte), surrounded by an enclosed courtyard (bailey). Images of battle horns, shields, and arrows as crucial ammunition shed light on military provisions and tactics for the time period.

William’s tactical use of cavalry is displayed in the “Cavalry” scene. The cavalry could advance quickly and easily retreat, which would scatter an opponent’s defenses allowing the infantry to invade. It was a strong tactic that was flexible and intimidating. Although foot soldiers are included in the tapestry, the cavalry commands the scene, thus presenting the impression that the Normans were a cavalry-dominant army.

In addition to depicting military tactics used in the Norman Conquest, the scene also provides visual evidence for eleventh-century battle gear. Cavalrymen are shown wearing conical steel helmets with a protective nose plate, mail shirts, and carrying shields and spears whereas the foot soldiers are seen carrying spears and axes. Representations of the cavalry show that the soldiers were armored but the horses were not. The brutality of war is evident in the battle scenes. Figures of mortally wounded men and horses are strewn along the tapestry’s lower zone as well as within the main central zone.

The Bayeux Tapestry provides an excellent example of Anglo-Norman art. It serves as a medieval artifact that operates as art, chronicle, political propaganda, and visual evidence of eleventh-century mundane objects, all at a monumental scale. This astounding work continues to fascinate.

Durham Cathedral: A Conversation

by Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

This conversation took place in Durham Cathedral (Durham, England), begun c. 1093. Speakers: Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris. The transcription has been abbreviated; watch the full video here: https://youtu.be/wlQCKsXEWS4

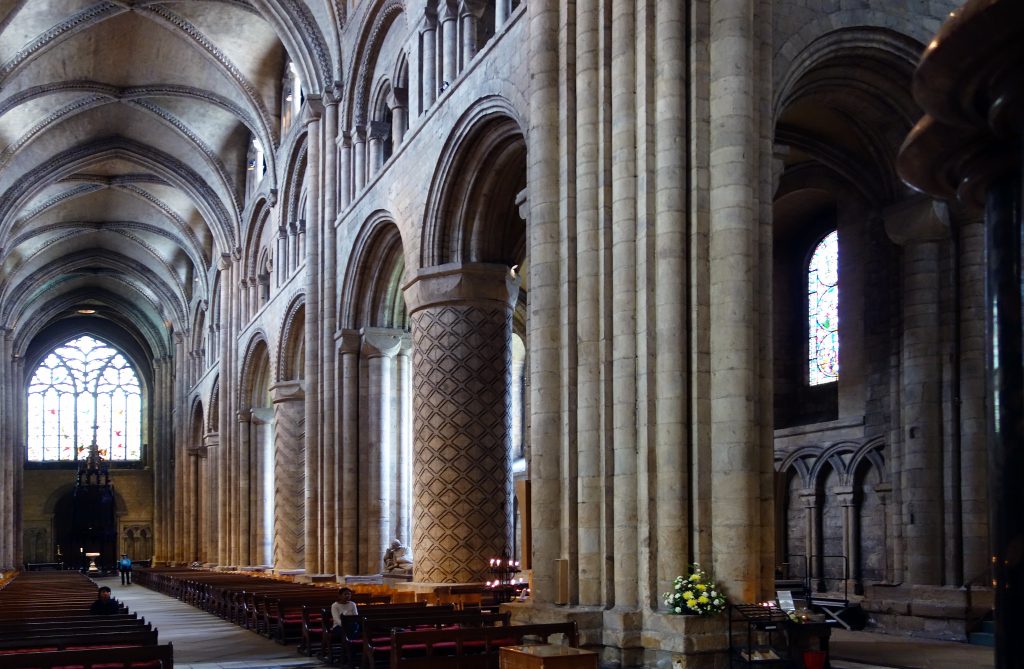

Steven: We’re in Durham Cathedral at the top of a hill in north eastern England. This is one of the great early cathedrals.

Beth: And it’s built less than three decades after the Norman Conquest, that is, after William the Conqueror crossed the channel with his army and invaded and took over England in a rather brutal invasion and replaced the old order of Anglo-Saxon England for this new Norman order, and built many churches, among the first of which is Durham Cathedral.…

Steven: English history is complicated. We have native peoples here that were conquered by the Romans who then left in the early fifth century. The political vacuum was then filled by invaders from what is now southern Denmark and northern Germany, peoples that we call the Angles and the Saxons, or the Anglo-Saxons.

Beth: And then Anglo-Saxon England is supplanted by Norman England and this is one of the first Anglo-Norman churches, and we feel the ancientness of this building. It is heavy, it feels fortified, and in that way we know that we’re standing in a Romanesque church.

Steven: This was some of the earliest large-scale architecture to take place since the Romans had left, and we call it Romanesque because this architecture was dependent on the technology that the Romans had originally used, that is the round arch.

Beth: One of the things that one notices immediately was how decorative the surfaces are, that is a key feature of Anglo-Norman Romanesque that differentiates it from what was going on on the French continent.

Steven: We’re standing in the nave and we’re surrounded by these massive piers that hold up the heavy vaulting above us, and there are basically two types of piers that alternate. One is a simple cylindrical pier, and the other is a more complex and larger compound pier that has attached columns.

Beth: And the cylindrical piers are the ones that carry this amazing linear decoration. When we walk in from the west and we see fluted columns. As we make our way east towards the holiest end of the church we see cylindrical piers decorated with chevrons, these zig-zag shapes. And then we come upon lozenge shapes, and in each case really deeply cut creating dark shadows that were likely originally painted.

Steven: And if you look closely you’ll notice that ingeniously the stonemasons created a kind of mass production, each stone is identical to another and yet when they fit together they create these continuous patterns.

Beth: And this is a testament to the increasing skill of stonemasons during the Romanesque period.…

Steven: The inter-elevation is three-part. Above the nave arcade is this broad, heavy .

Beth: I’m struck by the depth of the archway and the rolls of molding that lead our eye up to that gallery and we can see that in some cases that molding is decorated with that chevron zig-zag pattern in these wonderfully complex ways.

Steven: And we see that chevron zig-zag everywhere in this church. It creates the most lively pattern that activates the surfaces of stones.

Beth: Now the church is relatively dark as most Romanesque churches are. We can see a clerestory which is rather small and interestingly those windows are slightly inset, again we have a sense of the depth of the wall.

Steven: There is in fact a narrow walkway that moves just in front of those windows.

Beth: So this idea of emphasizing the depth of the wall, this interesting decorative carving, these are all things that art historians sees carrying through after the Romanesque into the English Gothic.

Steven: And one of my favorite decorative aspects of the church can be seen in the aisles. We see these doubled attached columns with these interlacing arches just above. It’s almost musical.

Beth: We have to imagine these painted in reds and greens and yellows so they would have really stood out. Art historians believe that these might be influenced by the art of Islamic Spain.

Steven: For example, in the great mosque at Cordoba we see interlacing similar to this. An aspect of this church that fascinates art historians is the vaulting, because here we see the precocious early use of ribbed vaulting.

Beth: Ribbed vaulting does in some form go back to the ancient Romans, but its use here is very important because we know what’s going to follow in the Gothic. Before stone vaulting, churches had been covered with wood, sometimes even flat wood ceilings. And so not only was stone vaulting more fireproof, it allowed for a shaping of space that was far more decorative.

Beth: If we follow the lines of the vault, we notice that it leads our eye down a shaft which is attached to the compound pier, and so you have this unifying of the nave from the ground all the way up through and across the transverse arch that takes to the other side of the nave. This unification of space is something that will become very important in the Gothic era….

from the Greek tympanon, drum, the space above the entrance to a church

an often-elaborate container for a relic

an artwork consisting of three pieces, often two wings flanking a central panel

from the Latin, "almond," a full-body halo in the shape of an almond

a marker of holiness, often in the form of a circle around an individual's head

a style of representation that seeks to recreate the visible world or nature

a channel for carrying water into Roman cities, often positioned atop an arcade

a true arch is a strong structural element in the shape of an inverted U, comprised of wedge-shaped blocks called voussoirs and held in place with a keystone. For a corbeled arch, see corbelling.

a tunnel comprised of arches, which may be simple (barrel vault), crossed (groin vault), or even stacked and pierced with windows (fenestrated groin vault)

an often remote, self-sufficient community of the faithful (monks) who have committed themselves to a life of religious devotion

a journey undertaken for spiritual purposes, including the answer to a prayer, forgiveness for a sin, or healing for oneself or another

individuals undertaking a pilgrimage

architectural and decorative elements removed from one monument for use on another

the wedge-shaped blocks used to construct a true arch

symbols of the four Gospel writers

in church architecture, the space between two columns in a nave arcade; an orderly division of the interior space

the element at the top of a column or pilaster

architectural elements similar to engaged columns, but flat rather than rounded

a textile with imagery woven directly into the cloth