11

Lumen Learning; Dr. Beth Harris; Dr. Nancy Ross; Dr. Steven Zucker; Dr. Evan Freeman; and Dr. Diane Reilly

In this chapter

Early Jewish and Christian Art

The Second Commandment and Its Interpretations

The Second Commandment, as noted in the Old Testament, warns all followers of the Hebrew god Yahweh, “Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.” As most Rabbinical authorities interpreted this commandment as the prohibition of visual art, Jewish artists were relatively rare until they lived in assimilated European communities beginning in the late eighteenth century.

Although no single biblical passage contains a complete definition of idolatry, the subject is addressed in numerous passages, so that idolatry may be summarized as the worship of idols or images; the worship of polytheistic gods by use of idols or images; the worship of trees, rocks, animals, astronomical bodies, or another human being; and the use of idols in the worship of God.

In Judaism, God chooses to reveal his identity, not as an idol or image, but by his words, by his actions in history, and by his working in and through humankind. By the time the Talmud was written, the acceptance or rejection of idolatry was a litmus test for Jewish identity. An entire tractate, the Avodah Zarah (strange worship) details practical guidelines for interacting with surrounding peoples so as to avoid practicing or even indirectly supporting such worship.

Attitudes towards the interpretation of the Second Commandment changed through the centuries. Jewish sacred art is recorded in the Tanakh and extends throughout Jewish Antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Tabernacle and the two Temples in Jerusalem form the first known examples of Jewish art.

Although first-century rabbis in Judea objected violently to the depiction of human figures and the placement of statues in temples, third-century Babylonian Jews had different views. While no figural art from first-century Roman Judea exists, the art on the Dura-Europos synagogue (Jewish house of worship) walls developed with no objection from the rabbis.

Illuminated Manuscripts and Mosaics

The Jewish tradition of illuminated manuscripts during Late Antiquity can be deduced from borrowings in Early Medieval Christian art. Middle Age Rabbinical and Kabbalistic literature also contain textual and graphic art, most famously the illuminated Haggadahs like the Sarajevo Haggadah, and manuscripts like the Nuremberg Mahzor. Some of these were illustrated by Jewish artists and some by Christians. Equally, some Jewish artists and craftsmen in various media worked on Christian commissions.

Byzantine synagogues also frequently featured elaborate mosaic floor tiles. The remains of a sixth-century synagogue were uncovered in Sepphoris, an important center of Jewish culture between the third and seventh centuries. The mosaic reflects an interesting fusion of Jewish and pagan beliefs.

In the center of the floor the zodiac wheel was depicted. The sun god Helios sits in the middle in his chariot, and each zodiac is matched with a Jewish month. Along the sides of the mosaic are strips that depict the binding of Isaac and other Biblical scenes.

The floor of the Beth: Alpha synagogue, built during the reign of Justinian I (518–527 CE), also features elaborate nave mosaics. Each of its three panels depicts a different scene: the Holy Ark, the zodiac and the story Isaac’s sacrifice. Once again, Helios stands in the center of the zodiac. The four women in the corners of the mosaic represent the four seasons.

As interpretations of the Second Commandment liberalized, any perceived ban on figurative depiction was not taken very seriously by the Jews living in Byzantine Gaza. In 1966, remains of a synagogue were found in the region’s ancient harbor area. Its mosaic floor depicts a syncretic image of King David as Orpheus, identified by his name in Hebrew letters. Near him are lion cubs, a giraffe and a snake listening to him playing a lyre.

A further portion of the floor was divided by medallions formed by vine leaves, each of which contains an animal: a lioness suckling her cub, a giraffe, peacocks, panthers, bears, a zebra, and so on. The floor was completed between 508 and 509 CE.

Dura-Europos

Dura-Europos, a border city between the Romans and the Parthians, was the site of an early Jewish synagogue dated by an Aramaic inscription to 244 CE. It is also the site of Christian churches and mithraea, this city’s location between empires made it an optimal spot for cultural and religious diversity.

The synagogue is the best preserved of the many imperial Roman-era synagogues that have been uncovered by archaeologists. It contains a forecourt and house of assembly with frescoed walls depicting people and animals, as well as a Torah shrine in the western wall facing Jerusalem.

The synagogue paintings, the earliest continuous surviving biblical narrative cycle, are conserved at Damascus, together with the complete Roman horse armor. Because of the paintings adorning the walls, the synagogue was at first mistaken for a Greek temple. The synagogue was preserved, ironically, when it was filled with earth to strengthen the city’s fortifications against a Sassanian assault in 256 CE.

The preserved frescoes include scenes such as the Sacrifice of Isaac and other Genesis stories, Moses receiving the Tablets of the Law, Moses leading the Hebrews out of Egypt, scenes from the Book of Esther, and many others. The Hand of God motif is used to represent divine intervention or approval in several paintings. Scholars cannot agree on the subjects of some scenes, because of damage, or the lack of comparative examples; some think the paintings were used as an instructional display to educate and teach the history and laws of the religion.

Others think that this synagogue was painted in order to compete with the many other religions being practiced in Dura-Europos. The new (and considerably smaller) Christian church (Dura-Europos church) appears to have opened shortly before the surviving paintings were begun in the synagogue. The discovery of the synagogue helps to dispel narrow interpretations of Judaism’s historical prohibition of visual images.

Early Christianity

By the early years of Christianity (first century), Judaism had been legalized through a compromise with the Roman state over two centuries. Christians were initially identified with the monotheistic Jewish religion by the Romans, but as they became more distinct, Christianity became a problem for polytheistic Roman rulers. Around the year 98, Nerva decreed that Christians did not have to pay the annual tax upon the Jews, effectively recognizing them as a distinct religion. This opened the way to the persecutions of Christians for disobedience to the emperor, as they refused to worship the state pantheon. The oppression of Christians was only periodic until the middle of the first century. However, large-scale persecutions began in the year 64 when Nero blamed them for the Great Fire of Rome earlier that year. Early Christians continued to suffer sporadic persecutions. Because of their refusal to honor the Roman pantheon, which many believed brought misfortune upon the community, the local pagan populations put pressure on the imperial authorities to take action against their Christians neighbors. The last and most severe persecution organized by the imperial authorities was the Diocletianic Persecution from 303 to 311. Many Christians were even killed. Those killed for their beliefs, regardless of the faith tradition, are known as martyrs.

Early Christian Art

Early Christian, or Paleochristian, art was produced by Christians or under Christian patronage from the earliest period of Christianity to, depending on the definition used, between 260 and 525. In practice, identifiably Christian art only survives from the second century onwards. After 550, Christian art is classified as Byzantine (see Chapter 12), or of some other regional type.

It is difficult to know when distinctly Christian art began. Prior to 100, Christians may have been constrained by their position as a persecuted group from producing durable works of art. Since Christianity was largely a religion of the lower classes in this period, the lack of surviving art may reflect a lack of funds for patronage or a small numbers of followers.

The Old Testament restrictions against the production of graven images (an idol or fetish carved in wood or stone) might have also constrained Christians from producing art. Christians could have made or purchased art with pagan iconography but given it Christian meanings. If this happened, “Christian” art would not be immediately recognizable as such.

Early Christians used the same artistic media as the surrounding pagan culture. These media included frescos, mosaics, sculptures, and illuminated manuscripts.

Early Christian art not only used Roman forms, it also used Roman styles. Late Classical art included a proportional portrayal of the human body and impressionistic presentation of space. The Late Classical style is seen in early Christian frescos, such as those in the Catacombs of Rome, which include most examples of the earliest Christian art.

Early Christian art is generally divided into two periods by scholars: before and after the Edict of Milan of 313, which legalized Christianity in the Roman Empire. The end of the period of Early Christian art, which is typically defined by art historians as being in the fifth through seventh centuries, is thus a good deal later than the end of the period of Early Christianity as typically defined by theologians and church historians, which is more often considered to end under Constantine, between 313 and 325.

Early Christian Painting

In a move of strategic syncretism, the Early Christians adapted Roman motifs and gave new meanings to what had been pagan symbols. Among the motifs adopted were the peacock, grapevines, and the “Good Shepherd.” Early Christians also developed their own iconography.

Such symbols as the fish (ikhthus), were not borrowed from pagan iconography. During the persecution of Christians under the Roman Empire, Christian art was necessarily and deliberately furtive and ambiguous, using imagery that was shared with pagan culture but had a special meaning for Christians. The earliest surviving Christian art comes from the late second to early fourth centuries on the walls of Christian tombs in the catacombs of Rome. From literary evidence, there might have been panel icons which have disappeared.

Depictions of Jesus

Initially, Jesus was represented indirectly by pictogram symbols such as the ichthys, the peacock, the Lamb of God, or an anchor. Later, personified symbols were used, including Daniel in the lion’s den, Orpheus charming the animals, or Jonah, whose three days in the belly of the whale prefigured the interval between the death and resurrection of Jesus. However, the depiction of Jesus was well-developed by the end of the pre-Constantinian period. He was typically shown in narrative scenes, with a preference for New Testament miracles, and few of scenes from his Passion. A variety of different types of appearance were used, including the thin, long-faced figure with long, centrally-parted hair that was later to become the norm. But in the earliest images as many show a stocky and short-haired beardless figure in a short tunic, who can only be identified by his context. In many images of miracles Jesus carries a stick or wand, which he points at the subject of the miracle rather like a modern stage magician (though the wand is significantly larger).

The image of The Good Shepherd, a beardless youth in pastoral scenes collecting sheep, was the most common of these images and was probably not understood as a portrait of the historical Jesus. These images bear some resemblance to depictions of kouroi figures in Greco-Roman art.

The almost total absence from Christian paintings during the persecution period of the cross, except in the disguised form of the anchor, is notable. The cross, symbolizing Jesus’s crucifixion, was not represented explicitly for several centuries, possibly because crucifixion was a punishment meted out to common criminals, but also because literary sources noted that it was a symbol recognized as specifically Christian, as the sign of the cross was made by Christians from the earliest days of the religion.

House Church at Dura-Europos

The house church at Dura-Europos is the oldest known house church. One of the walls within the structure was inscribed with a date that was interpreted as 231. It was preserved when it was filled with earth to strengthen the city’s fortifications against an attack by the Sassanians in 256 CE.

Despite the larger atmosphere of persecution, the artifacts found in the house church provide evidence of localized Roman tolerance for a Christian presence. This location housed frescos of biblical scenes including a figure of Jesus healing the sick.

When Christianity emerged in the Late Antique world, Christian ceremony and worship were secretive. Before Christianity was legalized in the fourth century, Christians suffered intermittent periods of persecution at the hands of the Romans. Therefore, Christian worship was purposefully kept as inconspicuous as possible. Rather than building prominent new structures for express religious use, Christians in the Late Antique world took advantage of pre-existing, private structures—houses.

The house church in general was known as the domus ecclesiae, Latin for house and assembly. Domi ecclesiae emerged in third-century Rome and are closely tied to domestic Roman architecture of this period, specifically to the peristyle house in which the rooms were arranged around a central courtyard.

These rooms were often adjoined to create a larger gathering space that could accommodate small crowds of around fifty people. Other rooms were used for different religious and ceremonial purpose, including education, the celebration of the Eucharist, the baptism of Christian converts, storage of charitable items, and private prayer and mass. The plan of the house church at Dura-Europos illustrates how house churches elsewhere were designed.

When Christianity was legalized in the fourth century, Christians were no longer forced to use pre-existing homes for their churches and meeting houses. Instead, they began to build churches of their own. Even then, Christian churches often purposefully featured unassuming—even plain—exteriors. They tended to be much larger as the rise in the popularity of the Christian faith meant that churches needed to accommodate an increasing volume of people.

Architecture of the Early Christian Church

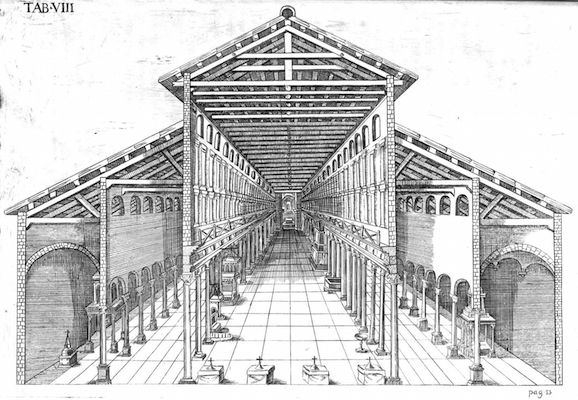

After their persecution ended in the fourth century, Christians began to erect buildings that were larger and more elaborate than the house churches where they used to worship. However, what emerged was an architectural style distinct from classical pagan forms. Architectural formulas for temples were deemed unsuitable. This was not simply for their pagan associations, but because pagan cult and sacrifices occurred outdoors under the open sky in the sight of the gods. The temple, housing the cult figures and the treasury, served as a backdrop. Therefore, Christians began using the model of the basilica, which had a central nave with one aisle at each side and an apse at one end.

Old St. Peter’s and the Western Basilicaapse

The basilica model was adopted in the construction of Old St. Peter’s church in Rome. What stands today is New St. Peter’s church, which replaced the original during the Italian Renaissance. Whereas the original Roman basilica was rectangular with at least one apse, usually facing North, the Christian builders made several symbolic modifications. Between the nave and the apse, they added a transept, which ran perpendicular to the nave. This addition gave the building a cruciform shape to memorialize the Crucifixion. The apse, which held the altar and the Eucharist, now faced East, in the direction of the rising sun. However, the apse of Old St. Peter’s faced West to commemorate the church’s namesake, who, according to the popular narrative, was crucified upside down.

A Christian basilica of the fourth or fifth century stood behind its entirely enclosed forecourt. It was ringed with a colonnade or arcade, like the stoa or peristyle that was its ancestor, or like the cloister that was its descendant. This forecourt was entered from outside through a range of buildings along the public street.

In basilicas of the former Western Roman Empire, the central nave is taller than the aisles and forms a row of windows called a clerestory. In the Eastern Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire, which continued until the fifteenth century), churches were centrally planned. The Church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy (discussed in the next chapter) is prime example of an Eastern church.

Christianity, an introduction

by Dr. Beth Harris, Dr. Nancy Ross and Dr. Steven Zucker

How little we know

Almost nothing is known about Jesus beyond biblical accounts, although we do know quite a bit more about the cultural and political context in which he lived—for example, Jerusalem in the first century. What follows is an introductory historical summary of Christianity. It hardly needs stating that there are many interpretations and disagreements among historians.

Jesus v. Rome

The biblical Jesus, described in the Gospels as the son of a carpenter, was a Jew and a champion of the underdog. He rebelled against the occupying Roman government in what was then Palestine (at this point the Roman Empire stretched across the Mediterranean). He was crucified for upsetting the social order and challenging the authority of the Romans and their local Jewish leaders. The Romans crucified Jesus, a typical method of execution—especially for those accused of crimes against the government.

Jesus’ followers claim that after three days he rose from the grave and later ascended into heaven. His original followers, known as disciples or apostles, traveled great distances and spread Jesus’ message. His life is recorded in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which are found in the New Testament. “Christ” means messiah or savior (this belief in a savior is a traditional part of Jewish theology).

Old and New Testaments

Early on, there were many ways that Christianity was practiced and understood, and it wasn’t until the 2nd century that Christianity began to be understood as a religion distinct from Judaism (it’s helpful to remember that Judaism itself had many different sects). Christians were sometimes severely persecuted by the Romans. In the early 4th century, the Roman Emperor Constantine experienced a miraculous conversion and made it legally acceptable to be a Christian. Less than a hundred years later, the Roman Emperor Theodosius made Christianity the official state religion.

The first Christians were Jews (whose bible we refer to as the Old Testament or the Hebrew Bible). But soon pagans too converted to this new religion. Christians saw the predictions of the prophets in the Hebrew Bible come to fulfillment in the life of Jesus Christ—hence the “Bible” of the Christians includes both the Hebrew Bible (or the Old Testament) and the New Testament.

In addition to the fulfillment of prophecy, Christians saw parallels between the events of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. These parallels, or foreshadowings, are called typology. One example would be Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son, Isaac, and the later sacrifice of Christ on the cross. We often see these comparisons in Christian art offered as a revelation of God’s plan for the salvation of mankind.

Different Christianities

Unlike Greek and Roman religions (there was both an official “state” religion as well as other cults), Christianity emphasized belief and a personal relationship with God. The doctrines, or main teachings, of Christianity were determined in a series of councils in the early Christian period, such as the Council of Nicea in 325. This resulted in a common statement of belief known as the Nicene Creed, which is still used by some churches today.

Nevertheless, there is great diversity in Christian belief and practice. This was true even in the early days of Christianity, when, for example, Arians (who believed that the three parts of the Holy Trinity were not equal) and Donatists (who held that priests who had renounced their Christian faith during periods of persecution could not administer the sacraments), were considered heretics (someone who goes against official teaching). Today there are approximately 2.2 billion Christians who belong to a multitude of sects.

The two dominant early branches of Christianity were the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, rooted in Western and Eastern Europe respectively. Protestantism (and its different forms) emerged only later, at the beginning of the sixteenth century. Before that there was essentially just one church in Western Europe—what we would call the Roman Catholic church today (to differentiate it from other forms of Christianity in the West such as Lutheranism, Methodism etc.). Christianity spread throughout the world. In the 16th century, the Jesuits (a Catholic order), sent missionaries to Asia, North and South America, and Africa often in concert with Europe’s colonial expansion.

Doctrines

Christianity holds that God has a three-part nature—that God is a trinity (God the father, the Holy Spirit, and Jesus Christ)* and that it was Jesus’s death on the cross—his sacrifice—that allowed for human beings to have the possibility of eternal life in heaven. In Christian theology, Christ is seen as the second Adam, and Mary (Jesus’s mother) is seen as the second Eve. The idea here is that where Adam and Eve caused original sin, and were expelled from paradise (the Garden of Eden), Mary and Christ made it possible for human beings to have eternal life in paradise (heaven), through Christ’s sacrifice on the cross.

Christian practice centers on the sacrament of the Eucharist, which is sometimes referred to as Communion. Christians eat bread and drink wine to remember Christ’s sacrifice for the sins of humankind. Christ himself initiated this practice at the Last Supper. Catholics and Eastern Orthodox believe that the bread and wine literally transform into the body and blood of Christ, whereas Protestants and other Christians see the Eucharist as symbolic reminder and re-enactment of Christ’s sacrifice.

Christians demonstrate their faith by engaging in good (charitable) works (works of art—like the frescoes by Giotto in the Arena Chapel—were often created as good works). They often engage in rituals (sacraments) such as partaking of the Eucharist or being baptized. Traditional Christian churches have a hierarchical structure of clergy. Devout men and women sometimes become nuns or monks and may separate themselves from the world and live a cloistered life devoted to prayer in a monastery.

*There are also nontrinitian Christians.

The Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Art

by Dr. Nancy Ross and Dr. Evan Freeman

Episodes from the life of Christ (many of which also include his mother, the Virgin Mary) were among the most common subjects depicted in Medieval and Renaissance art. But where do these stories come from? And what exactly do these images represent?

Most of these stories come from the Christian New Testament (the second part of the Christian Bible), and especially from the Gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, which record the life and teachings of Jesus. Some episodes are also associated with legends or non-biblical texts (texts that were not in the Bible, but were nevertheless read by Christians).

Some images of Christ’s life originated in the early centuries of the Church, including representations of Christ’s birth, which date to the fourth and fifth centuries. Many such images closely parallel the arts of the Eastern Roman “Byzantine” Empire. Other images developed later, such as Christ emerging from his tomb at the Resurrection, which appears in the eleventh century.

Medieval and Renaissance images of Christ’s life appear in a wide range of artistic media, on different scales, and in various public and private devotional settings. While these images vary based on the period, region, and circumstances of their production, this essay introduces common elements in scenes from the life of Christ, which had an enduring influence on the history of western art.

As usual, click on the images to view larger versions.

The Annunciation

The angel Gabriel visits the Virgin Mary to announce to her that she will be the mother of God. At this moment, Jesus Christ is miraculously conceived, and God becomes flesh and blood. The Annunciation is described in Luke 1:26–38 and pictured here in a fresco by Fra Angelico at the Convent of San Marco in Florence.

The Visitation

Mary and Elizabeth, who are cousins, meet, as shown in this fifteenth-century manuscript illumination. Mary (left) is pregnant with Jesus and Elizabeth (right) is pregnant with St. John the Baptist. Elizabeth (and her son in her womb) recognize the miracle of Christ in Mary’s womb. The Visitation is recorded in Luke 1:39-56. An angel sometimes stands near the Virgin, as in this miniature, although no angels are mentioned in the biblical account.

The Nativity

Matthew 1:18–2:12 and Luke 2:1–20 describe the Nativity of Christ. Mary gives birth to Christ in a stable while the animals watch. In Duccio’s Nativity, Joseph peers into the stable from the left side of the composition, while some other artworks show him sleeping (his minimized role in the scene emphasizes Mary’s virginity). The star that guides the Magi from the east shines overhead. A host of angels appear above the scene and announce Christ’s birth to shepherds. Midwives wash the newborn Christ child in the bottom left. View annotated image.

Adoration of the Magi

Three Magi (by tradition, kings from the East), follow a miraculous star that leads them to Christ, who has just been born in a stable (Matthew 2:1-12). The Magi offer gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh (frankincense and myrrh are aromatic tree resins), and worship the infant Christ. View annotated image.

Read about European depictions of Balthazar—one of the Magi—as an African king.

The Presentation

Mary and Joseph present Christ in the temple at Jerusalem as described in Luke 2:22–38. They encounter Simeon—who was told by the Holy Spirit that he would not die until he had seen the messiah—shown in Lorenzetti’s painting holding Christ into his arms. The prophetess Anna stands near Simeon, identifying Jesus as the Messiah with a pointing finger. View annotated image.

The Baptism of Christ

The Baptism of Christ is recounted in Matthew 3:13–17, Mark 1:9–11, and Luke 3:21–22 and appears here in the twelfth-century Psalter of Eleanor of Aquitaine. John the Baptist stands on the left, baptizing Christ in the Jordan River. A ministering angel stands on Christ’s other side, preparing to dress him when he emerges from the water. The Holy Spirit descends on Christ from above in the form of a dove. View annotated image.

The Temptation

Following Christ’s baptism, the Holy Spirit leads Christ into the wilderness to fast for forty days, during which time he is tempted by Satan (Matthew 4:1–11; Mark 1:12–13; Luke 4:1–12). Duccio’s painting depicts the third and final temptation: “The devil took him to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world…and he said to him, ‘All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.’ Jesus said to him, ‘Away with you, Satan! for it is written, “Worship the Lord your God, and serve only him.”‘ Then the devil left him, and suddenly angels came and waited on him.” (Matthew 4:8-11). View annotated image.

The Raising of Lazarus

The Raising of Lazarus, described in John 11:38–44, was one of the many miracles of Christ recorded in the Gospels. Christ was friends with Mary, Martha, and Lazarus, who were siblings. Lazarus becomes ill and his sisters send to Christ for help. Lazarus dies and is in the grave for four days before Christ raises him from the dead by calling him out of his tomb, shown on the right side of this fresco. View annotated image.

Entry into Jerusalem

Christ rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, where he is greeted by crowds of people (Matthew 21:1–11, Mark 11:1–10, Luke 19:29–40, and John 12:12–19). These crowds welcome him into Jerusalem by waving palm branches and laying down their cloaks for him. View annotated image.

Take a guided virtual tour of the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padova, Italy.

The Last Supper

Christ eats dinner with his apostles and encourages them to eat bread and drink wine in remembrance of him (Matthew 26:20–29; Mark 14:17–25; Luke 22:14–23; I Corinthians 11:23–26), as shown in this painting by Ugolino da Siena. He also tells the apostles that one of them will betray him. View annotated image.

Agony in the Garden

After the Last Supper, Christ goes to pray in the Garden of Gethsemane with his apostles (Matthew 26:36–46; Mark 14:32–42; Luke 22:39–46). He asks them to wait and pray with him, but they fall asleep. Anticipating his crucifixion, Jesus prays: “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me; yet, not my will but yours be done” (Luke 22:42). Artists often visualized Christ’s “cup” as a Eucharistic chalice, as in this miniature at the Getty Museum. In Luke’s Gospel, Christ’s anguish causes him to sweat blood, and an angel comes from heaven to strengthen Christ, two details that are sometimes also included in this scene. View annotated image.

Kiss of Judas

Judas, who has been paid 30 pieces of silver to betray Christ’s whereabouts to the Roman authorities, leads soldiers to Jesus and identifies him with a kiss, as shown here in Giotto’s fresco. Christ is arrested and led away. The episode is recorded in Matthew 26:47–56, Mark 14:–52, Luke 22:47–54, and John 18:1–11. View annotated image

Take a guided virtual tour of the Scrovegni (Arena) Chapel in Padova, Italy.

Christ before Pilate

Roman soldiers take Christ to Pilate, the Roman prefect (Matthew 27:11–26, Mark 15:1–15, Luke 23:1–25, John 18:28–19:16). Pilate tries Jesus, but does not find him guilty. Pilate tells the angry crowd that he will release one prisoner, but they do not choose Jesus. As in many artworks, Schongauer illustrates a moment from Matthew’s Gospel: “When Pilate saw that he could do nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took some water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood’” (Matthew 27.24). Pilate orders Christ to be whipped and crucified. View annotated image.

The Crucifixion

Christ is crucified at Golgotha as his mother Mary and John the Evangelist watch. Mary is sometimes accompanied by other women who were followers of Christ, as in this fourteenth-century painting at the Metropolitan. Jesus is offered vinegar (or sour wine) to drink from a sponge, and soon dies. He is stabbed in his side with a lance after his death. The Crucifixion is described in Matthew 27:32–56, Mark 15:21–41, Luke 23:26–49, and John 19:16–37. View annotated image.

Descent from the Cross (also known as The Deposition)

Pilate gives Joseph of Arimathea permission to remove Christ from the cross and bury his body (Matthew 27:57-61, Mark 15:42-47, Luke 23:50-56, John 19:38-42). Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, another follower of Christ, take Christ down from the cross. They bring a shroud for the body. Other figures often included in this scene are the Virgin Mary, St. John the Evangelist, and the three Marys (three women mentioned in the Gospels as followers of Christ, all named Mary but not including the Virgin Mary, Jesus’ mother).

The Marys at the Tomb

The Gospels describe women who followed Jesus as the first witnesses of Christ’s resurrection from the dead: Matthew 28:1–10, Mark 16:1–8, Luke 23:55–24:12, John 20:1–18. Tradition identified them as the three Marys: Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Mary Salome; a later tradition identified them as the three daughters of St. Anne. The Marys go to the tomb to wash and anoint the body of Christ, but when they arrive, the large stone is rolled away from the door. An angel tells the Marys that Christ is not there. The Getty miniature includes the soldiers that Pilate posted to guard Christ’s tomb, described in Matthew’s Gospel: “An angel of the Lord came down from heaven and, going to the tomb, rolled back the stone and sat on it. His appearance was like lightning, and his clothes were white as snow. The guards were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men” (Matthew 28:2-4). View annotated image.

The Resurrection

Christ emerges triumphant from the tomb and carries the banner of the resurrection, often a white flag with a red cross. This scene is not explicitly described in the Gospels and appears as early as the eleventh century.

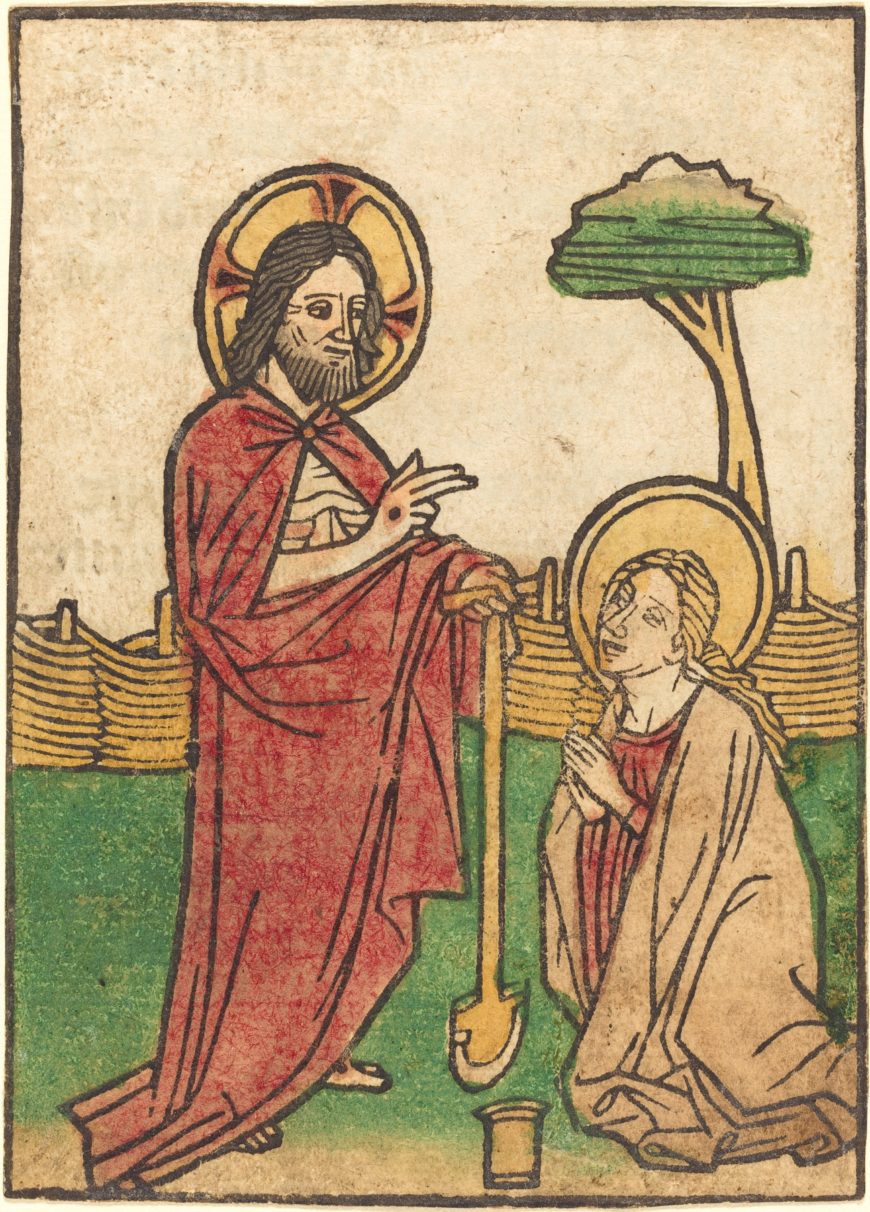

Noli me Tangere

Mary Magdalene goes to the tomb to mourn Christ (John 20:11-18). She finds Christ, but initially mistakes him for the gardener. Sometimes, as in this woodcut by Ludwig of Ulm, Christ appears with gardening tools (in this case a spade). When Mary realizes that he is Christ, he says “Touch me not” or “noli me tangere” in Latin.

The Ascension

After forty days with his disciples following his resurrection from the dead, Christ ascends into heaven (Luke 24:50–53, Acts 1:9–12). Sometimes, Christ is surrounded by a mandorla (an almond-shaped aureole of light). In other works, such as this English miniature, only Christ’s feet are visible as he ascends into the clouds above. The Virgin and Apostles stand below, gazing upward after Christ.

Pentecost

Pentecost depicts the descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles in the form of tongues of fire, as described in Acts 2. The Holy Spirit enables the Apostles to preach about the crucified and risen Christ in many languages so that people gathered in Jerusalem from many nations can understand. In this miniature, the Holy Spirit is also pictured as a dove, although this detail is not included in the biblical account.

Last Judgment

References to the Last Judgment appear in the Gospels and elsewhere in the Christian New Testament, and Christ is often represented in art as judge at the end of time. These scenes often show Christ enthroned in heaven surrounded by saints and angels, who help him judge the souls of humankind, as shown in the center panel of this triptych. Angels call forth the dead from their tombs to be judged, pictured in the bottom of the center panel. The righteous enter the Kingdom of Heaven, a beautiful orderly place (left panel), and the damned go to hell where they are tormented by demons (right panel). View annotated image.

Early Christian art

The beginnings of an identifiable Christian art can be traced to the end of the second century and the beginning of the third century. Considering the Old Testament prohibitions against graven images, it is important to consider why Christian art developed in the first place. The use of images will be a continuing issue in the history of Christianity. The best explanation for the emergence of Christian art in the early church is due to the important role images played in Greco-Roman culture.

As Christianity gained converts, these new Christians had been brought up on the value of images in their previous cultural experience and they wanted to continue this in their Christian experience. For example, there was a change in burial practices in the Roman world away from cremation to inhumation. Outside the city walls of Rome, adjacent to major roads, catacombs were dug into the ground to bury the dead. Families would have chambers or cubicula dug to bury their members. Wealthy Romans would also have sarcophagi or marble tombs carved for their burial. The Christian converts wanted the same things. Christian catacombs were dug frequently adjacent to non-Christian ones, and sarcophagi with Christian imagery were apparently popular with the richer Christians.

Junius Bassus, a Roman praefectus urbi or high ranking government administrator, died in 359 C.E. Scholars believe that he converted to Christianity shortly before his death accounting for the inclusion of Christ and scenes from the Bible. (Photograph above shows a plaster cast of the original.)

Themes of death and resurrection

A striking aspect of the Christian art of the third century is the absence of the imagery that will dominate later Christian art. We do not find in this early period images of the Nativity, Crucifixion, or Resurrection of Christ, for example. This absence of direct images of the life of Christ is best explained by the status of Christianity as a mystery religion. The story of the Crucifixion and Resurrection would be part of the secrets of the cult.

While not directly representing these central Christian images, the theme of death and resurrection was represented through a series of images, many of which were derived from the Old Testament that echoed the themes. For example, the story of Jonah—being swallowed by a great fish and then after spending three days and three nights in the belly of the beast is vomited out on dry ground—was seen by early Christians as an anticipation or prefiguration of the story of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Images of Jonah, along with those of Daniel in the Lion’s Den, the Three Hebrews in the Firey Furnace, Moses Striking the Rock, among others, are widely popular in the Christian art of the third century, both in paintings and on sarcophagi.

All of these can be seen to allegorically allude to the principal narratives of the life of Christ. The common subject of salvation echoes the major emphasis in the mystery religions on personal salvation. The appearance of these subjects frequently adjacent to each other in the catacombs and sarcophagi can be read as a visual litany: save me Lord as you have saved Jonah from the belly of the great fish, save me Lord as you have saved the Hebrews in the desert, save me Lord as you have saved Daniel in the Lion’s den, etc.

One can imagine that early Christians—who were rallying around the nascent religious authority of the Church against the regular threats of persecution by imperial authority—would find great meaning in the story of Moses of striking the rock to provide water for the Israelites fleeing the authority of the Pharaoh on their exodus to the Promised Land.

Christianity’s canonical texts and the New Testament

One of the major differences between Christianity and the public cults was the central role faith plays in Christianity and the importance of orthodox beliefs. The history of the early Church is marked by the struggle to establish a canonical set of texts and the establishment of orthodox doctrine.

Questions about the nature of the Trinity and Christ would continue to challenge religious authority. Within the civic cults there were no central texts and there were no orthodox doctrinal positions. The emphasis was on maintaining customary traditions. One accepted the existence of the gods, but there was no emphasis on belief in the gods.

The Christian emphasis on orthodox doctrine has its closest parallels in the Greek and Roman world to the role of philosophy. Schools of philosophy centered around the teachings or doctrines of a particular teacher. The schools of philosophy proposed specific conceptions of reality. Ancient philosophy was influential in the formation of Christian theology. For example, the opening of the Gospel of John: “In the beginning was the word and the word was with God…,” is unmistakably based on the idea of the “logos” going back to the philosophy of Heraclitus (ca. 535 – 475 BCE). Christian apologists like Justin Martyr writing in the second century understood Christ as the Logos or the Word of God who served as an intermediary between God and the World.

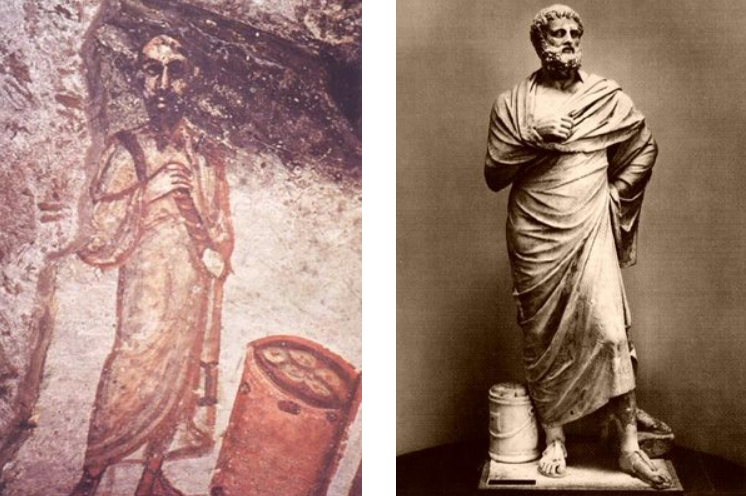

Early representations of Christ and the apostles

An early representation of Christ found in the Catacomb of Domitilla shows the figure of Christ flanked by a group of his disciples or students. Those experienced with later Christian imagery might mistake this for an image of the Last Supper, but instead this image does not tell any story. It conveys rather the idea that Christ is the true teacher.

Christ draped in classical garb holds a scroll in his left hand while his right hand is outstretched in the so-called ad locutio gesture, or the gesture of the orator. The dress, scroll, and gesture all establish the authority of Christ, who is placed in the center of his disciples. Christ is thus treated like the philosopher surrounded by his students or disciples.

Early Christian art and architecture after Constantine

By the beginning of the fourth century Christianity was a growing mystery religion in the cities of the Roman world. It was attracting converts from different social levels. Christian theology and art was enriched through the cultural interaction with the Greco-Roman world. But Christianity would be radically transformed through the actions of a single man.

Rome becomes Christian and Constantine builds churches

In 312, the Emperor Constantine defeated his principal rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Accounts of the battle describe how Constantine saw a sign in the heavens portending his victory. Eusebius, Constantine’s principal biographer, describes the sign as the Chi Rho, the first two letters in the Greek spelling of the name Christos.

After that victory Constantine became the principal patron of Christianity. In 313 he issued the Edict of Milan which granted religious toleration. Although Christianity would not become the official religion of Rome until the end of the fourth century, Constantine’s imperial sanction of Christianity transformed its status and nature. Neither imperial Rome or Christianity would be the same after this moment. Rome would become Christian, and Christianity would take on the aura of imperial Rome.

The transformation of Christianity is dramatically evident in a comparison between the architecture of the pre-Constantinian church and that of the Constantinian and post-Constantinian church. During the pre-Constantinian period, there was not much that distinguished the Christian churches from typical domestic architecture. A striking example of this is presented by a Christian community house, from the Syrian town of Dura-Europos. Here a typical home has been adapted to the needs of the congregation. A wall was taken down to combine two rooms: this was undoubtedly the room for services. It is significant that the most elaborate aspect of the house is the room designed as a baptistry. This reflects the importance of the sacrament of Baptism to initiate new members into the mysteries of the faith. Otherwise this building would not stand out from the other houses. This domestic architecture obviously would not meet the needs of Constantine’s architects.

Emperors for centuries had been responsible for the construction of temples throughout the Roman Empire. We have already observed the role of the public cults in defining one’s civic identity, and Emperors understood the construction of temples as testament to their pietas, or respect for the customary religious practices and traditions. So it was natural for Constantine to want to construct edifices in honor of Christianity. He built churches in Rome including the Church of St. Peter, he built churches in the Holy Land, most notably the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, and he built churches in his newly-constructed capital of Constantinople.

The basilica

In creating these churches, Constantine and his architects confronted a major challenge: what should be the physical form of the church? Clearly the traditional form of the Roman temple would be inappropriate both from associations with pagan cults but also from the difference in function. Temples served as treasuries and dwellings for the cult; sacrifices occurred on outdoor altars with the temple as a backdrop. This meant that Roman temple architecture was largely an architecture of the exterior. Since Christianity was a mystery religion that demanded initiation to participate in religious practices, Christian architecture put greater emphasis on the interior. The Christian churches needed large interior spaces to house the growing congregations and to mark the clear separation of the faithful from the unfaithful. At the same time, the new Christian churches needed to be visually meaningful. The buildings needed to convey the new authority of Christianity. These factors were instrumental in the formulation during the Constantinian period of an architectural form that would become the core of Christian architecture to our own time: the Christian Basilica.

The basilica was not a new architectural form. The Romans had been building basilicas in their cities and as part of palace complexes for centuries. A particularly lavish one was the so-called Basilica Ulpia constructed as part of the Forum of the Emperor Trajan in the early second century. Basilicas had diverse functions but essentially they served as formal public meeting places. One of the major functions of the basilicas was as a site for law courts. These were housed in an architectural form known as the apse. In the Basilica Ulpia, these semi-circular forms project from either end of the building, but in some cases, the apses would project off of the length of the building. The magistrate who served as the representative of the authority of the Emperor would sit in a formal throne in the apse and issue his judgments. This function gave an aura of political authority to the basilicas.

The basilica at Trier (Aula Palatina)

Basilicas also served as audience halls as a part of imperial palaces. A well-preserved example is found in the northern German town of Trier. Constantine built a basilica as part of a palace complex in Trier which served as his northern capital. Although a fairly simple architectural form and now stripped of its original interior decoration, the basilica must have been an imposing stage for the emperor. Imagine the emperor dressed in imperial regalia marching up the central axis as he makes his dramatic adventus or entrance along with other members of his court. This space would have humbled an emissary who approached the enthroned emperor seated in the apse.

Editor’s Note: The wide central aisle is called a nave, from the Latin word for ship. Indeed, the rafters of a ceiling like Old St. Peter’s, as shown above, would look like the ribs of an inverted ship hull. Both Old St. Peter’s Basilica and the Aula Palatina have a longitudinal plan, meaning they’re arranged along a single central axis, here culminating at the altar. This is intentionally different from the central plan of pagan temples like the Pantheon.

Classicism and the Early Middle Ages

by Dr. Diana Reilly

In 1942 a farmer plowing a field in the East of England unearthed a substantial hoard of Roman silver dating from the fourth century, C.E. This became known as the “Mildenhall Treasure,” named for the nearby town. Its original owner may have buried his collection of banqueting vessels when the Roman administration left England in 410 C.E., hoping that he could later retrieve it. Among the spoons, bowls, dishes, and ladles is a two-foot wide silver platter weighing almost eighteen pounds, with classical motifs borrowed from antiquity (ancient Greece and Rome). However, though the platter depicts the gods Neptune and Bacchus, the owner was likely a follower of Christianity—a newly-sanctioned religion that was not yet the dominant belief system in Europe. This confluence of classical and Christian concepts is typical of the early middle ages. Because of the political and social upheavals happening in Europe at this time, the art of this period comprises a wide range of styles and themes that often blend classical elements with new and different ones.

A “decline”?

The transition between antiquity and the Middle Ages is often perceived as having been marked by a sharp break in beliefs and artistic style. This change was, in the past, characterized by scholars as a “decline.” According to this narrative, the chaotic and unstable atmosphere of the Roman Empire in the later third century led many of its inhabitants to embrace new, minority religions imported from the empire’s edges. Some of these were messianic religions that promised members an afterlife more pleasant than their current, increasingly difficult existences. At the same time, the economic struggles of the Late Roman Empire undermined investment in the artists’ workshops where the naturalism of classical Roman art had been taught to generations of artists. Lacking the traditional training, means, and patrons who valued classicism, artists during this period often worked in a more static, two-dimensional style that emphasized ideas and symbols over naturalistic illusionism. The abandonment of naturalistic style also coincided, it seemed, with the rise of a new majority religion, Christianity, that rejected materiality and traditional forms of beauty in favor of simplicity and self-denial.

Two stone reliefs installed on the Arch of Constantine demonstrate this supposed “decline.” The reused roundel with a sacrifice to Apollo (left) originally carved for a monument to the Emperor Trajan between 117 and 138 (when the Roman empire was more stable), displays many key characteristics of classicism: varied depth of relief, carefully delineated drapery folds, and figures shifting in space. By contrast, in the panel depicting the emperor distributing largesse (right), commissioned in the Late Empire between 312 and 315, the figures seem almost comically disproportionate, with enormous heads and hands, and draperies indicated by drilled lines.

The problem with the idea of a “decline” is that it ignores the many, often contradictory, currents of art and experience that existed in the late antique world. Romans had long sought to incorporate newly conquered and colonized populations by appropriating local religious beliefs and artistic traditions, in the process creating new, localized versions of Roman art that were sometimes less naturalistic. Even artists working in the capital, Rome, could choose to employ either naturalism or a more symbolic visual shorthand, depending on who made the art and who consumed it—as in the Amiternum Tomb (above), which was made during the first century, when classicism was the most prominent style. Instead of displaying a classical attention to composition, the artist has arrayed stocky figures of a variety of sizes in a seemingly haphazard way—going against the current artistic trends of the day.

Classicism survives

If works like the Amiternum Tomb help complicate the idea of an artistic decline, do they perhaps simply demonstrate variances in artists’ and patrons’ tastes? Some have argued that Emperor Constantine (who decriminalized Christianity in Rome in the early fourth century), and by extension the increasingly Christian populace, were, because of their beliefs, drawn to a non-classical style that denied naturalism in favor of a more symbolic set of forms. But surviving artworks commissioned by wealthy Romans show that, like their pagan peers, many Christians often still preferred a classicizing style—even if the subjects portrayed were new. For instance, in the middle of the fourth century the body of Junius Bassus, a Roman prefect (high official), was buried in an elaborate marble sarcophagus.

Since he was a Christian convert, Junius’s sarcophagus was covered with narrative and symbolic scenes from the Christian bible, all rendered in a classicizing style. The standing apostles are wrapped in Roman togas and the youthful Christ sits on a sella curulis, the animal-headed and -footed chair of the governing classes. Unlike most classical works, here the hands and heads of the figures are a little too large, but the artist was clearly attempting to employ the stylistic language of classicism to transmit Christian content.

These aesthetic departures from strict classicism were not limited to Christian-sponsored art: the same tendencies are apparent in objects that were commissioned by avowed pagans around the same time. This ivory panel was commissioned to celebrate a marriage between members of two Roman patrician (noble) families, the Nicomachi and Symmachi. A female figure with an oversized head and hands stands next to an altar, while a comparatively tiny servant stands behind it. The woman’s back leg projects in front of the surrounding frame, while her front leg, counterintuitively, stands on the ground within it, breaking the rules of naturalism. Based on the artworks that survive, we know that both pagan and Christian patrons found these kinds of contradictions in space and proportion acceptable.

A hoard of silver

There were also a diversity of themes preferred amongst patrons of different religions. Artworks from this time sometimes combine overtly pagan content with classicizing style, but for use by Christians. The so-called “Great Dish” found in the Mildenhall treasure is a shining example of such artistic combinations. Concentric rings of repoussé and engraved decoration celebrate the classical themes of the ocean and Bacchic revelry. The hair and beard of the Roman god Neptune in the center of the dish radiate dolphins and seaweed. Around him nymphs ride sea creatures.

In the outer band Bacchus (the god of wine), Hercules, Pan and throngs of satyrs and maenads holding Bacchic thistle-headed staffs and a shepherd’s crook twist and turn, draperies swirling, dancing with wine-induced abandon.

While this dish’s classicizing style and subject matter are undeniable, we known that its owner was likely Christian, as spoons from his dinnerware set (below) include the Christian symbols of the Chi-Rho and Alpha and Omega. Despite his Christianity, the owner likely felt perfectly comfortable displaying the platter with its exuberant dancing nudes on his sideboard for the admiration of his guests.

Rather than demonstrating a “decline” or a sharp break in artistic themes and styles, Roman artworks of the early middle ages display as much diversity and blending as the empire itself.

the holy text of Judaism

characterized by a belief in one god

those killed for their beliefs; often with religious connotations

decree issued by Constantine in 313 CE which legalized Christianity

[From Greek eikon meaning "image" + glúphō meaning "to carve" or "to write"] The visual images and symbols used in a work of art or the study or interpretation of these [Art History Glossary]

from the Latin word for ship, the long central aisle of a basilica or cathedral

a straight passageway. In a Christian basilica, side aisles flank a main central aisle (see nave)

in architecture, a recess, usually semicircular, in the wall of a Roman basilica or at one end of a church, often the east end [Art History Glossary]

having the shape of the cross; a common layout for early and later Christian churches

one of the rites of the Christian church, it is based on Biblical scripture that quotes Jesus at the Last Supper telling His apostles to remember Him with a ritual of eating bread--"It is my body"--and drinking wine--"It is my blood"; also known as "Holy Communion" or "The Lord's Supper" [Art History Glossary]

a row of evenly-placed columns

a row of arches placed side by side

the four books from the Christian New Testament that record the life of Jesus: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John

the original followers of Jesus, also known as apostles

a book containing the Psalms from the Hebrew Bible

the sacred vessel that holds the wine, believed to be transformed into the blood of Christ, in the Catholic Mass

one of the four authors of the Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John

a story or symbol from the Jewish Bible that is seen to prefigure, or predict, an event in the life of Christ

stone coffin, from the Greek word for limestone ("sarkophagos"), from sark (flesh) + phage (eat)

a symbol of Christianity formed by overlapping the first three letters in the Greek spelling of the name Christos (Christ)

in architecture, describes a plan arranged along a single central axis, culminating at the altar

in architecture, the arrangement of the structural elements around a central point, often in a circle or octagon (compare to longitudinal plan)

religions that include a messiah figure who is promised to save believers

a style of representation that seeks to recreate the visible world or nature

relating to the style and values of ancient Greek and Roman art

sculpture that, unlike free-standing or in-the-round sculpture, doesn't detach entirely from its background. High-relief sculpture projects far from the background, whereas low-relief, or bas-relief sculpture is relatively shallow.