17

Valerie Spanswick; Dr. Steven Zucker; Dr. Beth Harris; Louisa Woodville; Dr. Nancy Ross; and Meg Bernstein

In this chapter

Forget the association of the word “Gothic” to dark, haunted houses, Wuthering Heights, or ghostly pale people wearing black nail polish and ripped fishnets. The original Gothic style was actually developed to bring sunshine into people’s lives, and especially into their churches. To get past the accrued definitions of the centuries, it’s best to go back to the very start of the word Gothic, and to the style that bears the name.

The Goths were a so-called barbaric tribe who held power in various regions of Europe, between the collapse of the Roman Empire and the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire (so, from roughly the fifth to the eighth century). They were not renowned for great achievements in architecture. As with many art historical terms, “Gothic” came to be applied to a certain architectural style after the fact.

The style represented giant steps away from the previous, relatively basic building systems that had prevailed. The Gothic grew out of the Romanesque architectural style, when both prosperity and relative peace allowed for several centuries of cultural development and great building schemes. From roughly 1000 to 1400, several significant cathedrals and churches were built, particularly in Britain and France, offering architects and masons a chance to work out ever more complex and daring designs.

The most fundamental element of the Gothic style of architecture is the pointed arch, which was likely borrowed from Islamic architecture that would have been seen in Spain at this time. The pointed arch relieved some of the thrust, and therefore, the stress on other structural elements. It then became possible to reduce the size of the columns or piers that supported the arch.

So, rather than having massive, drum-like columns as in the Romanesque churches, the new columns could be more slender. This slimness was repeated in the upper levels of the nave, so that the gallery and clerestory would not seem to overpower the lower arcade. In fact, the column basically continued all the way to the roof, and became part of the vault.

In the vault, the pointed arch could be seen in three dimensions where the ribbed vaulting met in the center of the ceiling of each bay. This ribbed vaulting is another distinguishing feature of Gothic architecture. However, it should be noted that prototypes for the pointed arches and ribbed vaulting were seen first in late-Romanesque buildings.

The new understanding of architecture and design led to more fantastic examples of vaulting and ornamentation, and the Early Gothic or Lancet style (from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries) developed into the Decorated or Rayonnant Gothic (roughly fourteenth century). The ornate stonework that held the windows–called tracery–became more florid, and other stonework even more exuberant.

The ribbed vaulting became more complicated and was crossed with lierne ribs into complex webs, or the addition of cross ribs, called tierceron. As the decoration developed further, the Perpendicular or International Gothic took over (fifteenth century). Fan vaulting decorated half-conoid shapes extending from the tops of the columnar ribs.

The slender columns and lighter systems of thrust allowed for larger windows and more light. The windows, tracery, carvings, and ribs make up a dizzying display of decoration that one encounters in a Gothic church. In late Gothic buildings, almost every surface is decorated. Although such a building as a whole is ordered and coherent, the profusion of shapes and patterns can make a sense of order difficult to discern at first glance.

After the great flowering of Gothic style, tastes again shifted back to the neat, straight lines and rational geometry of the Classical era. It was in the Renaissance that the name Gothic came to be applied to this medieval style that seemed vulgar to Renaissance sensibilities. It is still the term we use today, though hopefully without the implied insult, which negates the amazing leaps of imagination and engineering that were required to build such edifices.

Basilica of Saint Denis, Paris: A Conversation

By Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This conversation occurred in the birthplace of the Gothic period, the Basilica of Saint Denis, near Paris. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/2EciWH-1ya4

BETH HARRIS: Here we are at the Basilica of Saint Denis.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: The birthplace of the Gothic.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Thanks to Suger, who was the abbot in the first half of the 12th century. This church is incredibly important because it’s the burial place of the royal family. Suger himself was also a advisor to the royal family.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: We’re standing in the choir. And light is pouring in the windows.

DR. BETH HARRIS: So the choir is the space behind the altar of the church. And the is the aisle that would take one behind the altar.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: Actually, it’s taking us around behind the altar.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Now, Suger completed the ambulatory and also the façade of the church.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: And none of this was new construction. There had been a ninth-century church here. And Suger felt that it was inadequate as the burial place of the kings. At this historical moment, the kings of France only really controlled the Isle de France, that is, the area immediately around Paris. But this was a time when the king’s power was expanding. And Suger really wanted to create an architectural style that would express the growing power of the monarch. Now, in the history of Western church architecture, the way that this would generally work is you would have an ambulatory that would move around the back of the altar. And that would allow pilgrims to stop at each of these small, radiating chapels, that is, these small rooms that would contain relics.

DR. BETH HARRIS: In the past during the Romanesque period, these chapels would be literally separate rooms with walls around them. And Suger’s idea was instead to open up the space and to allow light to flood in. And that’s exactly how this looks. And it must have looked so different than anything anyone had seen before.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: Instead of this looking like a set of walls that are pierced by windows—and in the Romanesque, relatively small windows—instead, he’s figured out how to engineer this structure in stone. So that the walls can basically disappear and be replaced by glass—colored glass—that lets this brilliant, luminous color into the space. So let’s talk about two things—how he did this, and second of all, why he did this.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Which one should we do first?

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: Well, let’s talk about how he did it. If you look above us, there’s this complex web of interlocking pointed vaulting.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Pointed arches are really key here, because for one thing, you can cover spaces of different shapes and sizes. Perhaps most importantly, a pointed arch doesn’t push so much out as it does it down. And because of that, the architect didn’t need to build thick walls.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: A traditional Roman arch generally has to be placed on quite heavy walls, because it really does push outward. It splays. What the pointed arch does is it tends to take the weight of the vaulting and push it more straight down, so that the weight doesn’t have to be buttressed from the side.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Looking up at those ribs, we have a sense of a pull toward the vertical. And all of these ribs in this vaulting rests on these thin columns. So there’s a real sense of elegance and openness to this space.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: And it’s so radically different from the Romanesque that came before, which felt so solid and where your eye was always drawn around that rounded arch back down. And you felt the sense of gravity. You felt a sort of rootedness with the Romanesque. And it is so different here. You have to remember the church itself, any consecrated church, is an expression of the holy Jerusalem. It is Heaven on Earth. And so the idea is how can one transport us to a more heavenly place, to a more spiritual place. Abbot Suger believed that light could do this.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Suger thought he was reading the writing of Saint Denis, of the patron saint of this church.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: Instead, he was reading a philosopher from the sixth century. But the important part is he took this notion of the divinity of light from that writing and made that practical and applicable within an architectural setting.

DR. BETH HARRIS: Right. That writing that he thought was by Saint Denis talked about how light was connected to the divine. So what Suger wanted was to open up those walls and allow in the light that would allow a type of thinking on the part of the visitors where they would move from the contemplation of the light to God.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: This was a radical and new notion and actually flew in the face of other theological theories of the time. And if you think about the ideas that are being established by Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who’s saying, we have to get rid of all the decorative. We have to get rid of everything that will distract us. Suger is moving in the other direction and saying, no, in fact. We can transport people.

DR. BETH HARRIS: That the visual is not a distraction but a way of transporting us to the divine.

DR. STEVEN ZUCKER: I have to say that I think Suger was incredibly successful. This is startlingly beautiful. And I feel transported.

Editor’s Note: Abbot Suger had a name for that “divine light” that Dr. Harris and Dr. Zucker are talking about here: lux nova. “New light” in Latin, lux nova is the heavenly aura created by the windows, often of colorful stained glass, that now pierce and almost dissolve the walls. For Suger, who wrote a whole treatise on his renovations at Saint Denis, beauty served to elevate the mind—and for him, beauty was all about light. We see that in the inscription for the doors:

All you who seek to honor these doors,

Marvel not at the gold and expense but at the craftsmanship of the work.

The noble work is bright, but, being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten the minds, allowing them to travel through the lights

To the true light, where Christ is the true door.

The golden door defines how it is imminent in these things.

The dull mind rises to the truth through material things,

And is resurrected from its former submersion when the light is seen.

An inscription in the upper choir likewise celebrates the beauty and divine significance of this new light:

When the new rear part is joined to that in front,

The church shines, brightened in its middle.

For bright is that which is brightly coupled with the bright

And which the new light pervades,

Bright is the noble work Enlarged in our time

I, who was Suger, having been leader

While it was accomplished.

Translation by David Burr, as provided at Fordham University’s Medieval Sourcebook.

Chartres Cathedral: a conversation

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

This is the transcript of a conversation conducted in Chartres Cathedral in Chartres, France. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/Jk3VsinLgvc

Steven: We’re in the town of Chartres, about an hour’s train ride from Paris, looking at the great medieval cathedral, Notre Dame de Chartres.

Beth: It’s easy to think about this church as a day trip from Paris, but back in the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries, the town of Chartres was a major destination unto itself.

Steven: But it’s important that we understand it within the orbit of Paris, because Gothic as a style developed in Île-de-France—that is, the area around Paris that was ruled by the king of France. We think now of France as a nation with stable borders, but in the medieval period, the king only controlled the area immediately around Paris, and it was in this area that the architectural style of Gothic first developed.

Beth: Chartres was a destination for a very particular reason: it had, and still has, the tunic that the Virgin Mary wore (it was believed) when she gave birth to Christ.

Steven: As the Virgin Mary’s importance grew during the medieval period, the importance of this church—and specifically of this relic—grew.

Beth: We’re looking at the cathedral today with apartments and cafés around it, but this was once part of a complex of buildings that included a school, a palace for the bishop, a hospital… In fact, the School of Chartres, an educational institution very much akin to a university, was very important and famous during the Gothic period.

Steven: Many other people associated with the School of Chartres believed that the pursuit of knowledge—learning about the world around us—was the pathway to understanding the divine.

Beth: And they were studying the texts of the ancient Greeks and Romans, of Aristotle and Plato.

Steven: In fact, we can see the impact of the School of Chartres in some of the sculpture that adorns the west doorway.

Beth: we west façade of Chartres dates to the mid twelfth century, and so we see it as an early Gothic façade. That’s obvious when we compare it to a High Gothic thirteenth-century church like Amiens, where the portal is pierced everywhere and there’s almost no sense of masonry, no sense of the stone. But here, the windows on either side of the doorway are quite small.

Steven: In fact, the first story of the towers still recalls the Romanesque. The windows are actually rounded and very little of the wall is given over to openings. we architects were still nervous about supporting the enormous weight that was to be piled above.

Beth: That’s because stone vaulting, the ceiling of these churches, are enormously heavy.

Steven: This is all solid limestone.

Beth: And they exert tremendous pressure downward and outward, and so you need these very strong walls and piers to support the weight of that stone vaulting.

Steven: The façade is fairly simple. From left to right, there are basically three parts. A tower on the left, the central area, and the tower on the right. If we go from bottom to top, we also have a division of three.

Beth: At the very top we see what’s known as a Kings Gallery, Old Testament royal figure. Below that, the beautiful round rose window. These are very typical of Gothic architecture. This is using something called plate tracery. We have primary a sense of the stone and then opening within that, as opposed to bar tracery, where we have just these thin bars that separate the panes of the stained glass windows.

Steven: We’ll see that especially in later windows in places like Amiens. Now below the rose window are three large lancets and these vertical windows reflect the portals below them.

Beth: The three portals are covered with sculpture. Anyone walking into this church would read something in the pictures. Let’s talk about the parts of the Gothic portal. At the very top, we see sculptures within the archivolts and the archway that is framed by archivolts is known as a tympanum.

Steven: Below that, supporting each of the tympana is a lintel. wat is a kind of crossbeam of stone. Those are supported by small engaged columns known as colonettes that line each side of the three doors. Those are really door jambs and attached to those are figures which are known therefore as jamb figures.

Beth: What’s interesting is that they’re angled inward, and so we’re invited to enter the church.

Steven: This front porch is quite shallow compared to what will happen at, say, Amiens.

Beth: For the doorways become almost funnels into the church.

Steven: The archivolts protrude outward, creating canopies. Overall, this front is really fairly modest compared to what happens in the Gothic. Nevertheless, it is one of the most important and one of the earliest fully-conceived sculptural programs. Let’s get close and take a look. When I was in school, the three tympana were taught to me as follows. we tympanum on the let showed the Ascension of Christ. we largest of the three, the tympanum in the middle, showed the Second Coming of Christ. we tympanum on the right showed scenes that related to the life of the Virgin Mary. But things have changed.

Beth: We have a new interpretation, and that is that the portal on the left, instead of depicting the Ascension, depicts Christ before he takes on physical form.

Steven: That is, a Christ out of time.

Beth: Before the incarnation, before God has made flesh. Below, we see four angels.

Steven: And probably my favorite part of this is the way that the angels try to reach below the barrier that separates them from the prophets. Some of the prophets don’t seem to have any idea that there’s anything above them, although a few have cocked their head with some interest.

Beth: Well, they’re prophets. They begin to see the future, they begin to understand God’s plan for mankind but they can’t see it entirely.

Steven: In order to see that, we have to go to the right tympanum, the tympanum devoted to the Virgin Mary…

Beth: …who makes possible God taking on physical form and entering the world so that we can be saved.

Steven: Let’s start with the lintel. We can make out a winged figure. This is archangel Gabriel announcing to the Virgin Mary that she will bear Christ.

Beth: And next to this we see a scene known as the Visitation, where Mary is visited by her cousin Elizabeth. Mary is pregnant with the Christ child, and her cousin Elizabeth is pregnant with Saint John the Baptist.

Steven: Then the most important scene in the lintel, the center. Here we see Mary in the manger having just given birth to the Christ child who’s swaddled just above her.

Beth: And just to the right, a scene of the Adoration of the three Shepherds have come to honor the Christ child.

Steven: Above this, we see the presentation of Christ in the temple.

Beth: Mary and Joseph have brought the Christ child to the temple.

Steven: wen above that, in the tympanum, we see the Virgin Mary enthroned with the Christ child on her lap with angels on either side. This represents the Throne of Wisdom.

Beth: When Christ is shown seated on Mary’s lap, Mary’s body is understood as the Throne of Wisdom. Christ is understood as the personification of wisdom.

Steven: Mary, in turn, is understood as that throne, but also as the church itself.

Beth: Both Mary and Christ as shown frontally, very symmetrically, and Mary is enthroned here as the queen of heaven. On the let, we had an image of Christ before the incarnation, before taking human form. On the right, we have the moment when Christ enters the world in order to save it. wen in the center, we have the Second Coming of Christ, when the dead rise from their graves and all of mankind is judged.

Steven: What’s important, though, is that that is the end of time. So a period before time, a period of human time, and a period at the end of time.

Beth: Christ is surrounded by symbols of the four Evangelists—

Steven: –the four writers of the Gospels. And he is shown in the center larger than any other figure. This is called hieratic scale, emphasizing his relative importance. He is shown seated on the throne of heaven surrounded by a mandorla…

Beth: A large, full-bodied halo. Below him, we see 12 figures. These are the 12 apostles. Now, the jamb figures are especially beautiful here at Chartres. These represent Old Testament prophets and kings and queens, and by association, the kings and queens of France.

Steven: The jambs of the westwork are my favorite figures at Chartres. They’re so long and attenuated. They’re so solid and so elegant.

Beth: You’ll notice that each figure is attached to a column and each figure resembles a column. And so there’s an interdependence between the architecture and the sculpture that adorns it.

Steven: It seems natural to wonder why the figures have been so abstracted, why they’re so absurdly long. Or even why their feet seem to be dangling down a bit.

Beth: These are heavenly, divine figures. They’re not meant to look physical and on this earth. They’re meant to look transcendent. If you look at the drapery, the falls are indicated by lines.

Steven: There’s a very little sense of mass. Instead, there’s a real emphasis on the linear.

Beth: By the time of the High Gothic period, and, in fact, on other later sculpted portals here at Chartres, we’ll see figures who have much more volume, figures become more human.

Steven: Another important attribute is their sense of isolation. Each figure seems isolated from the figures beside it.

Beth: That, too, will change on the later sculpted portals at Chartres and at other High Gothic cathedrals.

Steven: But we’ve been talking about the portals. I think we ought to use the doors. Let’s go in… We’ve walked into the cathedral and we’re entering into this long space, which was based on a basilica plan.

Beth: A basilica is a type of building that Christians borrowed from the ancient Romans. It’s longitudinal. It has an entrance on one end, opposite that is the apse, the holiest part of the church.

Steven: If you were to look at the church from a bird’s eye view, you would see that the church sketches the shape of a cross because it is the long hallway, the nave, that is crossed by something called the transept.

Beth: Here at Chartres, the north and south transept also have doorways that are sculpted.

Steven: This church is a little more complicated because, on either side of the nave, there are auxiliary hallways known as aisles. This was so that pilgrims, that is religious visitors, could enter the church and move through to the apse and around the other side without disturbing a mass that might be taking place.

Beth: Those pilgrims were primarily here to see the famous relic of the tunic of the Virgin, and later another relic that was acquired by the cathedral, the head of Saint Anne, the Virgin Mary’s mother.

Steven: In fact, the most famous relic of this church, the tunic of the Virgin Mary, played a very important role in the church that we’re now sitting in. We were looking at the west front and that was part of a church that dated to 1145. But in 1194, there was a terrible fire and most of the church burned to the ground.

Beth: But miraculously, two priests saved the tunic of the Virgin Mary. When the people of Chartres saw that the tunic was saved, they interpreted this as a miracle, one with a message: that the Virgin Mary wanted an even more beautiful and grander church to house her relic.

Steven: And that’s the church that we’re in now.

Beth: The west front of the church that survived the fire is decidedly Early Gothic. The church that we’re sitting in now that was built after the fire is clearly the beginning of the High Gothic style.

Steven: That’s probably most clear if we look at the interior elevation, because unlike earlier Gothic churches like at Paris where there was a four-part elevation, here we have a three-part elevation.

Beth: The three-part elevation consists of a nave arcade, these very tall, pointed arches that are very slender and graceful.

Steven: That’s the lowest level.

Beth: On top of that, we see an arcade standing in front of a wall and that area is called the triforium. Above that, we see very tall clerestory windows. In this case, each bay of the nave we see two lancet windows topped by an oculus.

Steven: we three segments of the elevation are united by the piers and the colonettes that are attached to the piers. You can see them soaring from the pavement below all the way up.

Beth: We have that interest in linearity and these lines that draw our eye upward that are so typical of Gothic architecture. As we follow those colonettes up, we see that they divide into ribs that form the four-part ribbed groin vaults that constitute the ceiling, the vaulting of this church.

Steven: The pointed ribbed groin vault allowed for greater height than a round arch would, and that’s because a pointed ribbed groin vault pushes its trust more down than out.

Beth: And as a result, it can rest on smaller piers and not as much buttressing is required. We should say that one of the primary goals of the Gothic architect was to open up the walls to the stained glass, glass that helped to make the interior a space that recalled the divine, that gave one a sense of heaven here on earth. One of the ways you could do that was with a flying buttress essentially supporting the building from the outside.

Steven: Instead of having massive walls within the church, much of the weight is supported by flying buttresses that help support the lateral thrust of the building. While flying buttresses are beautiful architectural elements in their own right, they were really subservient to the idea of allowing the walls to open up to allow for more glass, for more light to enter into the church. But this wasn’t aesthetic. we idea was that light itself was an expression of the divine and nowhere is this more evident than in Chartres where more of the original glass survives from the medieval era.

Beth: That glass has largely this lovely deep blue color that’s especially associated with Chartres. There’s also reds and golds creating a space that makes you feel as though you’re almost inside of a jewel, with light refracting in all different ways.

Steven: It is still stunning. It’s still spectacular. One can only imagine the impression this glass would have made in the twelfth century, when most people’s clothing was earth colors, where painting was rare.

Beth: Where windows in your houses were very small and so coming into this space was a transcendent experience. We’re so fortunate to be here today when so much of the restoration work on the interior has been completed and we can see that the walls have been cleaned. They used to be a dark brownish gray. we conservators here have painted the stone the way that is was painted in the twelfth and thirteenth century.

Steven: Somewhat unexpectedly, the stone was covered with a thin layer of plaster and then painted onto that was this light ochre color with white lines painted on top of it to mimic the joinery of the stones below, but not accurately. That layer of plaster and paint obscures the true masonry.

Beth: Nineteenth- and twentieth-century visitors to Chartres talked about how dark it was, but they were seeing it with centuries of grime and we are fortunate today to begin to see it the way that it looked in the thirteenth century.

Steven: Let’s walk down towards the apse and take a look at one particularly famous stained glass window.

Beth: One that dates from the early Gothic period from before the fire.

Steven: This tall window is sometimes known as the “Virgin of Beautiful Window.” we blue contrast against the red is extraordinary. It looks like the window is made out of rubies and sapphires. Mary is frontal. Here, again, we see Mary as the throne of wisdom.

Beth: Mary is elongated. Both of the figures are strictly frontal. We’re clearly looking at a heavenly image and not an earthly image, but a projection of the divine.

Steven: At the end of the north transept is an enormous rose window on top of the lancets. This is a much bigger rose than what we’ve seen in the earlier west front.

Beth: This was paid for by Blanche of Castile, the mother of Saint Louis, King Louis IX, who was a major patron of Gothic art.

Steven: We can see fleur-de-lis throughout this window, a reference to the French monarchy.

Beth: In the center of the rose, we once again see the Virgin Mary holding the Christ child. Surrounding Mary we see doves and angels and then prophets and kings.

Steven: For example, in the 12 o’clock position we see King David.

Beth: When we look at the lancets below, we see in the center Saint Anne, Mary’s mother. Remember that the cathedral acquired the relic of the head of Saint Anne, so it’s appropriate that she’s honored here in this window.

Steven: And she’s holding the infant Mary.

Beth: Then the two lancet windows on either side, we see these interesting pairings of virtuous and villainous kings, and also Old Testament priests.

Steven: For example, the lancet just to the let of Anna shows King David, and the smaller figure, Saul, who is shown with a sword through his chest.

…

Steven: We’ve walked out the south transept and the porch is so different from the west front.

Beth: Here we’re about 80 or so years after the sculpture on the west façade and things are really different for Gothic architecture and Gothic sculpture.

Steven: we porch projects much more than the west front did, which is a characteristic of the High Gothic, but the jamb figures have changed so so much.

Beth: Well, before we saw a real interdependence between the figure and the architecture. we figure looked like a column, and it was in front of a column. Here the figures are still in front of columns, but they have an independence from the architecture, which is entirely new.

Steven: The most famous figure on the south porch is Saint Theodore, and you can see why.

Beth: Well, he looks almost like an ancient Greek or a Roman figure. We see that the body has movement. we jamb figures on the west portal were so elongated and static.

Steven: They were columnar.

Beth: And they had no sense of liveliness to them. Theodore seems almost as though he could walk oy the porch and greet us.

Steven: His right hip juts out and it creates this Gothic sway. Just look at the feet. His feet are firmly planted, whereas the figures on the west front seem to dangle, somehow, in midair.

Beth: In his right hand he carries a spear with a banner, and we see much more than on the west front a sense of volume to the drapery, especially when we look to the hem of the garment where we see real three dimensional folds.

Steven: Theodore is still attached to the column.

Beth: We can’t call him free-standing.

Steven: But he does seem animated.

Beth: In his belt, we see the hilt of a sword, and his let-hand rests on a shield, which is pressed against his thigh. There’s a naturalism to his movement and the way he carries himself that tells us we’re now in the High Gothic period.

Steven: we Cathedral at Chartres is remarkable for so many reasons. But what I love about it, especially, is the way that it represents the evolution of the Gothic style, from the columnar jamb figures on the west work to the High Gothic representations that we see on the south porch.

Beth: I’m so glad we decided to spend the day at Chartres.

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris

The fire

The blaze that engulfed the Cathedral [/ simple_tooltip] of Notre Dame [/ simple_tooltip] on the small Island known as the Île de la Cité in Paris in April 2019 was a terrible tragedy. Though it may not give us much comfort to learn that the total or partial destruction of churches by fire was a fairly common occurrence in medieval Europe, it does provide some perspective. For example, a fire destroyed most of Chartres Cathedral in 1020 (and again in 1194), in the city of Reims, the cathedral was badly damaged in a fire in 1210, and at Beauvais, the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in the 1180s. The list goes on and on.

During the medieval periods of the Romanesque and the Gothic (c. 1000-1400), church fires were less frequent than they had been previously due to the development of stone vaulting (which began to replace the timber ceilings commonly found in European churches). But even a stone vault, as we saw at Notre Dame in Paris, is itself protected by a timber roof (sometimes rising more than 50 feet above the stone vaulting and pitched to prevent the accumulation of rain and snow), and this is what caught fire.

Art historian Caroline Brazelius, who has worked on the building for years said, “between the vaults and the roof, there is a forest of timber” — old, dry, porous, and highly flammable timber. Still, photographs of the interior show at least some of the stone vaulting survived the recent fire. The builders of Notre Dame used Parisian limestone, but, as Brazelius notes, “when it’s exposed to fire, stone is damaged. It doesn’t actually burn….It becomes friable. It chips, and it’s no longer structurally sound.”

Built, modified, rebuilt, and restored

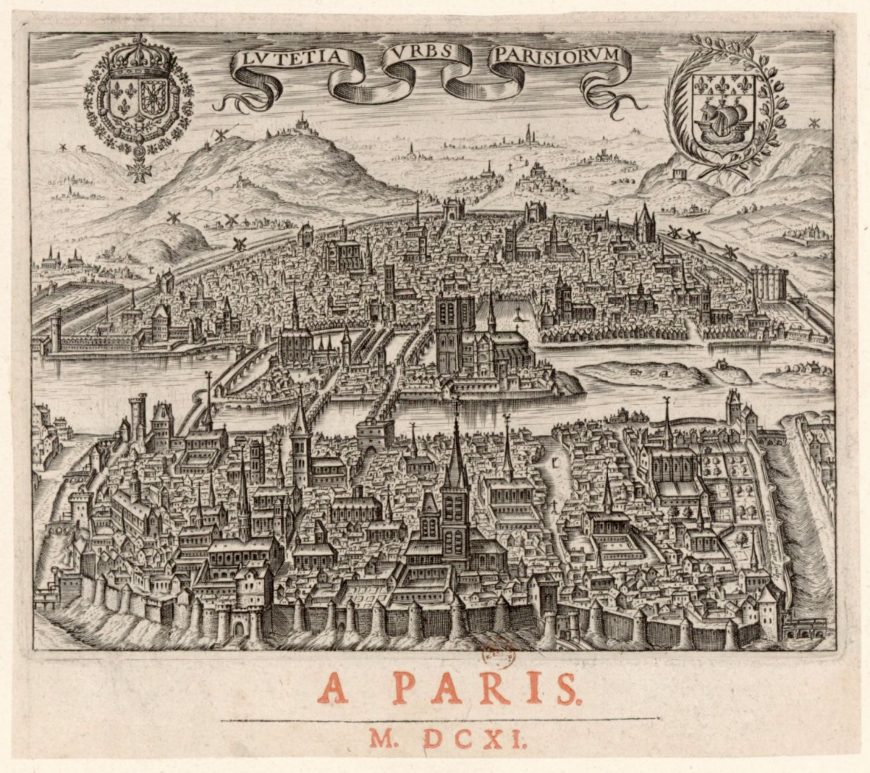

Churches are often an amalgamation of architectural styles, the result of building campaigns and modifications undertaken at different times, some due to fire, some due to the desire for what a new style represents, and some due to (often inaccurate) restoration efforts. And on a single site, churches were often built and rebuilt — and this is the case with Notre Dame in Paris. Before the Gothic-style church was built, a Carolingian church occupied the site (it was destroyed during the 9th century Viking invasions), and before that, a 6th century Merovingian Church stood on the site.

If we go back further, to the pre-Christian era, Julius Caesar’s armies famously conquered much of what we call France today (Roman Paris dates back to 52 BCE). Archaeological evidence suggests that a pagan temple and then a Christian basilica were built on this site. The ancient Romans also built a palace for the emperor on the Île de la Cité, and after the Roman empire collapsed, Clovis I, King of the Franks (who converted to Christianity) established his palace there as well. The Île de la Cité would remain the location of a royal residence until the 14th century. As one historian has noted, “Notre Dame … was not only a religious but also a royal monument that displayed the might of the church and the monarchy, each enhancing the power of the other.”[1]

The Gothic Cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris took nearly 100 years to complete (c. 1163-1250) and modifications, restorations, and renovations continued for centuries after. The early Gothic style employed at the beginning of the campaign became outdated and the later Gothic style, the Rayonnant, became fashionable and can be seen in the transepts. The crossing spire that the world watched fall while engulfed in flames was a reproduction created during a 19th-century restoration campaign.

In the following centuries, the church (and its sculptural decoration) survived multiple episodes of intentional destruction: during the Protestant Reformation (due to Protestant objection to religious imagery), and during the revolutions of 1789 and 1830 (because of the church’s close association with the monarchy). It remained in a neglected state until Victor Hugo’s novel, The Hunchback of Notre-Dame (1831) revived popular interest the building.

As of this writing, just a few days after the April 15th blaze, evaluation of the damage caused by the fire is only just beginning, but a reported one billion dollars has been already been raised to support the reconstruction of Notre Dame de Paris.

Sainte-Chapelle (Paris): A Conversation

By Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris

This is a conversation between Dr. Steven Zucker and Dr. Beth Harris. To watch the video: https://youtu.be/vigjJih8Pn4.

Steven: We’ve walked into the courtyard of what had once been the palace of the king of France and in the center is a jewel box, Sainte-Chapelle.

Beth: This was the royal chapel, this was a chapel attached to the Royal Palace for the use of the king and his household but it’s much more than that.

Steven: We walked in through the lower chapel which was used by the king’s household into the upper channel which was used by the king, by the queen and by the court.

Beth: In fact, there are niches on either side for the king and queen. At the far end was a reliquary and this was the whole point of Sainte-Chapelle.

Steven: The king Saint Louis had obtained one of the great relics of Christendom, the Crown of Thorns. This was part of the passion of Christ. Beth: And of course, a crown is symbolic of royalty and this was the chapel of Saint Louis also known as King Louis IX.

Steven: Saint Louis was able to purchase the crown from his cousin who was the Byzantine emperor.

Beth: For an enormous sum.

Steven: And I think it’s important to just step back and think about what that crown signified. The faithful believe that the crown had touched Christ, had made him bleed. And the idea of the relic is central. It collapses time, it brings Christ into our immediate experience.

Beth: Now, relics were incredibly important in Medieval culture. They performed miracles.

Steven: Extremely ornate boxes were produced in order to house them and in some ways one can imagine that this entire chapel functions metaphorically as a reliquary for the Crown of Thorns.

Beth: It’s said that more than three quarters of this building is made of glass. There’s light flooding in. It’s a light that is golden and red and blue and purple.

Steven: This is a crowning achievement of gothic architecture. The lancet windows soar upward pointing our eyes towards heaven.

Beth: And typically we see the four part ribbed groin vaults.

Steven: And bundled colonettes that make the masonry feel more delicate. In fact, the masonry has been reduced to almost nothing, really just mullions, that is slender, vertical forms that separate the windows.

Beth: But we’re here in the 13th century beyond the high gothic. A period that art historians called the Rayonnant where we have this emphasis on thin line and the total opening up of the walls to windows, which was always a goal of gothic architecture but here taken to such an extreme. Over the west door we see this enormous rose window. Now, rose windows were a typical feature of gothic architecture but during this Rayonnant period, the stone tracery that make up the stained glass window becomes thinner and more attenuated and more complex.

Steven: Now, the windows are not just beautiful, they tell stories. Each window refers to either an old or new testament story or a story referring to the acquisition of the relic. We see a window representing the moment when Christ has the crown of thorns placed on his head, the crown that by tradition was held in this church.

Beth: This is dense with imagery. In addition to the stained glass windows, we have sculptures of the apostles that stand between the windows. We have quatrefoils that depict scenes of martyrdom and there are also angels in the spandrels many of whom hold crowns, some swing censors.

Steven: A reminder of what the space would have been like when it was still used as a church. So, imagine this space filled with music, filled with the voice of the priest, filled with the smoke of the incense with colored lights streaming through. It is this beautiful mystical space.

Beth: In addition to there being so much imagery, so much of the surfaces are painted. There are reds and golds and blues, there’s almost nothing that would remind us that this is a building made of stone.

Steven: This completely open the interior space with so much glass seems absolutely miraculous. It is a testament to the sophistication of gothic architects during this late period. There seems like there’s not nearly enough stone to hold this building up. Let’s go outside and take a look at how this was achieved. We’ve walked out of the chapel and what strikes me is that the building really stands alone. It’s tall and it’s thin but here we are in the middle of the Ile de la Cite, a small island in the middle of modern Paris.

Beth: And in the 13th century at the very time that Sainte-Chapelle was built, Paris was becoming the capital that we know it as today.

Steven: We can see how the building structure works from the outside. The actual responsibility for bearing the great weight of the stone vaulting is carried by the buttresses which we can see on the exterior. All of that weight was brought outside but the buttresses are kept fairly small in order to ensure that light can enter in the windows which creates another problem. The lateral force of the roof is pushing outward and these buttresses on their own wouldn’t be enough to support the roof.

Beth: There is an additional structural element that was added to help ensure the stability of the building. There are iron rods that act like a kind of girdle to counter the thrust of the vaulting down and out.

Steven: Some art historians have pointed out that the exterior top of the building looks rather like a crown.

Beth: If we look up toward the top of Saint-Chapelle, we see gables and in between the gables those buttresses. But the buttresses have on top of them these tall pinnacles and we almost read that alternations of gables and pinnacles as the points on a crown.

Steven: And in fact the phrase Sainte-Chapelle is a specific type of chapel, that is a chapel within the palace grounds and that holds a relic.

Saint Louis Bible (Moralized Bible or Bible moralisée)

Blanche of Castile

In 1226 a French king died, leaving his queen to rule his kingdom until their son came of age. The 38-year-old widow, Blanche of Castile, had her work cut out for her. Rebelling barons were eager to win back lands that her husband’s father had seized from them. They rallied troops against her, defamed her character, and even accused her of adultery and murder.

Caught in a perilous web of treachery, insurrections, and open warfare, Blanche persuaded, cajoled, negotiated, and fought would-be enemies after her husband, King Louis VIII, died of dysentery after only a three-year reign. When their son Louis IX took the helm in 1234, he inherited a kingdom that was, for a time anyway, at peace.

A manuscript illumination

A dazzling illumination in New York’s Morgan Library could well depict Blanche of Castile and her son Louis, a beardless youth crowned king. A cleric and a scribe are depicted underneath them (see image at the top of the page). Each figure is set against a ground of burnished gold, seated beneath a trefoil arch. Stylized and colorful buildings dance above their heads, suggesting a sophisticated, urban setting—perhaps Paris, the capital city of the Capetian kingdom (the Capetians were one of the oldest royal families in France) and home to a renowned school of theology.

A moralized Bible

This last page the New York Morgan Library’s manuscript MS M 240 is the last quire (folded page) of a three-volume moralized bible, the majority of which is housed at the Cathedral Treasury in Toledo, Spain. Moralized bibles, made expressly for the French royal house, include lavishly illustrated abbreviated passages from the Old and New Testaments. Explanatory texts that allude to historical events and tales accompany these literary and visual readings, which—woven together—convey a moral.

Assuming historians are correct in identifying the two rulers, we are looking at the four people intensely involved in the production of this manuscript. As patron and ruler, Queen Blanche of Castile would have financed its production. As ruler-to-be, Louis IX’s job was to take its lessons to heart along with those from the other biblical and ancient texts that his tutors read with him.

King and queen

In the upper register, an enthroned king and queen wear the traditional medieval open crown topped with fleur-de-lys—a stylized iris or lily symbolizing a French monarch’s religious, political, and dynastic right to rule. The blue-eyed queen, left, is veiled in a white widow’s wimple. An ermine-lined blue mantle drapes over her shoulders. Her pink T-shaped tunic spills over a thin blue edge of paint which visually supports these enthroned figures. A slender green column divides the queen’s space from that of her son, King Louis IX, to whom she deliberately gestures across the page, raising her left hand in his direction. Her pose and animated facial expression suggest that she is dedicating this manuscript, with its lessons and morals, to the young king.

Louis IX, wearing an open crown atop his head, returns his mother’s glance. In his right hand he holds a scepter, indicating his kingly status. It is topped by the characteristic fleur-de-lys on which, curiously, a small bird sits. A four-pedaled brooch, dominated by a large square of sapphire blue in the center, secures a pink mantle lined with green that rests on his boyish shoulders.

In his left hand, between his forefinger and thumb, Louis holds a small golden ball or disc. During the mass that followed coronations, French kings and queens would traditionally give the presiding bishop of Reims 13 gold coins (all French kings were crowned in this northern French cathedral town.) This could reference Louis’ 1226 coronation, just three weeks after his father’s death, suggesting a probable date for this bible’s commission. A manuscript this lavish, however, would have taken eight to ten years to complete—perfect timing, because in 1235, the 21-year-old Louis was ready to assume the rule of his Capetian kingdom from his mother.

A link between earth and heaven

Queen Blanche and her son, the young king, echo a gesture and pose that would have been familiar to many Christians: the Virgin Mary and Christ enthroned side-by-side as celestial rulers of heaven, found in the numerous Coronations of the Virgin carved in ivory, wood, and stone. This scene was especially prevalent in tympana, the top sculpted semi-circle over cathedral portals found throughout France. On beholding the Morgan illumination, viewers would have immediately made the connection between this earthly Queen Blanche and her son, anointed by God with the divine right to rule, and that of Mary, Queen of heaven and her son, divine figures who offer salvation.

A cleric and an artist

The illumination’s bottom register depicts a tonsured cleric (churchman with a partly shaved head), left, and an illuminator, right.

The cleric wears a sleeveless cloak appropriate for divine services—this is an educated man—and emphasizes his role as a scholar. He tilts his head forward and points his right forefinger at the artist across from him, as though giving instructions. No clues are given as to this cleric’s religious order, as he probably represents the many Parisian theologians responsible for the manuscript’s visual and literary content—all of whom were undoubtedly told to spare no expense.

On the right, the artist, donning a blue surcoat and wearing a cap, is seated on cushioned bench.

Knife in his left hand and stylus in his right, he looks down at his work: four vertically-stacked circles in a left column, with part of a fifth visible on the right. We know, from the 4887 medallions that precede this illumination, what’s next on this artist’s agenda: he will apply a thin sheet of gold leaf onto the background, and then paint the medallion’s biblical and explanatory scenes in brilliant hues of lapis lazuli, green, red, yellow, grey, orange and sepia.

Advice for a king

Blanche undoubtedly hand-picked the theologians whose job it was to establish this manuscript’s guidelines, select biblical passages, write explanations, hire copyists, and oversee the images that the artists should paint. Art and text, mutually dependent, spelled out advice that its readers, Louis IX and perhaps his siblings, could practice in their enlightened rule. The nobles, church officials, and perhaps even common folk who viewed this page could be reassured that their ruler had been well trained to deal with whatever calamities came his way.

This 13th century illumination, both dazzling and edifying, represents the cutting edge of lavishness in a society that embraced conspicuous consumption. As a pedagogical tool, perhaps it played no small part in helping Louis IX achieve the status of sainthood, awarded by Pope Bonifiace VIII 27 years after the king’s death. This and other images in the bible moralisée explain why Parisian illuminators monopolized manuscript production at this time. Look again at the work. Who else could compete against such a resounding image of character and grace?

Röttgen Pietà

An emotional response

It is hard to look at the Röttgen Pietà and not feel something—perhaps revulsion, horror, or distaste. It is terrifying and the more you look at it, the more intriguing it becomes. This is part of the beauty and drama of Gothic art, which aimed to create an emotional response in medieval viewers.

Earlier medieval representations of Christ focused on his divinity (left). In these works of art, Christ is on the cross, but never suffers. These types of crucifixion images are a type called Christus triumphans or the triumphant Christ. His divinity overcomes all human elements and so Christ stands proud and alert on the cross, immune to human suffering.

Triumphant Christ / Patient Christ

In the later Middle Ages, a number of preachers and writers discussed a different type of Christ who suffered in the way that humans suffered. This was different from Catholic writers of earlier ages, who emphasized Christ’s divinity and distance from humanity.

Late medieval devotional writing (from the 13th-15th centuries) leaned toward mysticism and many of these writers had visions of Christ’s suffering. Francis of Assisi stressed Christ’s humanity and poverty. Several writers, such as St. Bonaventure, St. Bridget of Sweden , and St. Bernardino of Siena, imagined Mary’s thoughts as she held her dead son. It wasn’t long before artists began to visualize these new devotional trends. Crucifixion images influenced by this body of devotional literature are called Christus patiens, the patient Christ.

The effects of this new devotional style, which emphasized the humanity of Christ, quickly spread throughout western Europe through the rise of new religious orders (the Franciscans, for example) and the popularity of their preaching. It isn’t hard to see the appeal of the idea that God understands the pain and difficulty of being human. In the Röttgen Pietà, Christ clearly died from the horrific ordeal of crucifixion, but his skin is taut around his ribs, showing that he also led a life of hunger and suffering.

Pietà statues appeared in Germany in the late 1200s and were made in this region throughout the Middle Ages. Many examples of Pietàs survive today. Many of those that survive today are made of marble or stone but the Röttgen Pietà is made of wood and retains some of its original paint. The Röttgen Pietà is the most gruesome of these extant examples.

Many of the other Pietàs also show a reclining dead Christ with three dimensional wounds and a skeletal abdomen. One of the unique elements of the Röttgen Pietà is Mary’s response to her dead son. She is youthful and draped in heavy robes like many of the other Marys, but her facial expression is different. In Catholic tradition, Mary had a special foreknowledge of the resurrection of Christ and so to her, Christ’s death is not only tragic. Images that reflect Mary’s divine knowledge show her at peace while holding her dead son. Mary in the Röttgen Pietà appears to be angry and confused. She doesn’t seem to know that her son will live again. She shows strong negative emotions that emphasize her humanity, just as the representation of Christ emphasizes his.

All of these Pietàs were devotional images and were intended as a focal point for contemplation and prayer. Even though the statues are horrific, the intent was to show that God and Mary, divine figures, were sympathetic to human suffering, and to the pain, and loss experienced by medieval viewers. By looking at the Röttgen Pietà, medieval viewers may have felt a closer personal connection to God by viewing this representation of death and pain.

Four styles of English medieval architecture at Ely Cathedral

Four styles of English medieval architecture

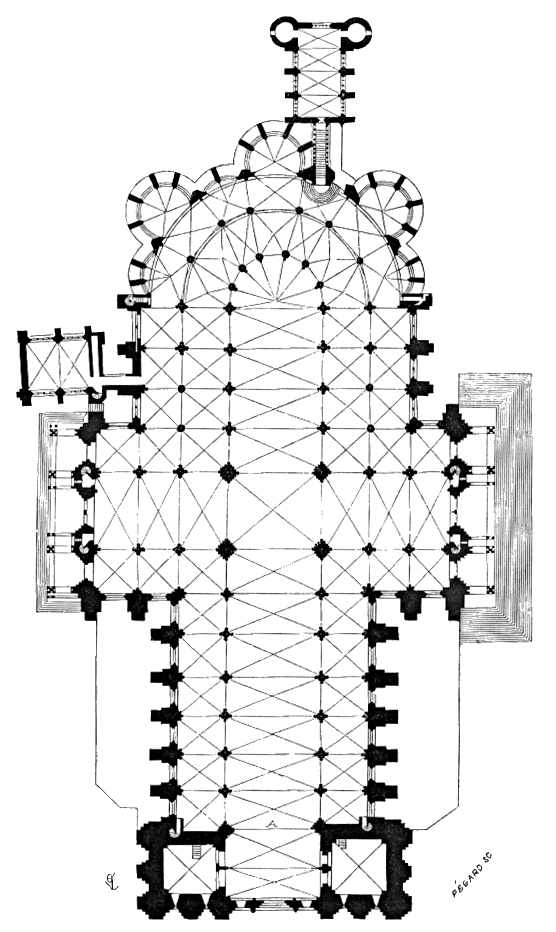

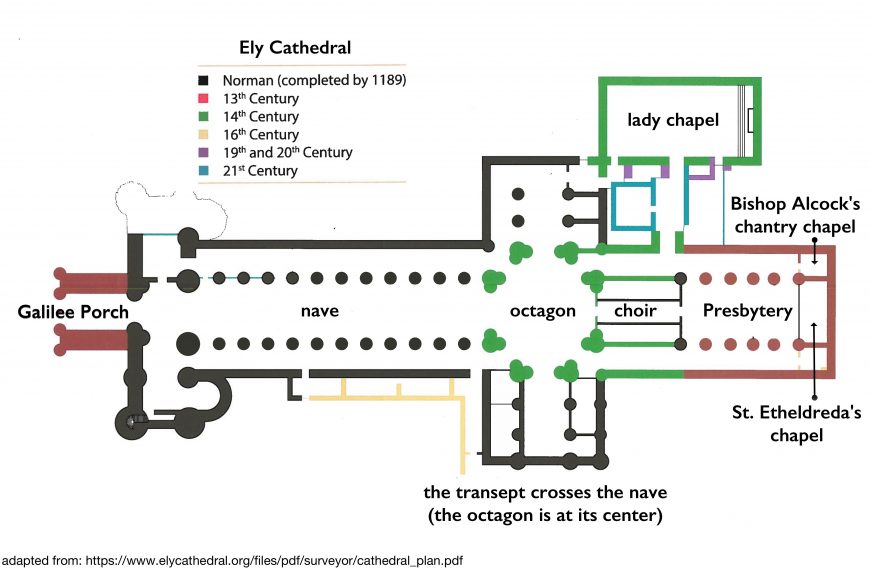

Ely Cathedral, like nearly all medieval English cathedrals, saw many different phases of construction. Major building projects in the Middle Ages were both expensive and time-consuming, so renovations and additions were made piecemeal rather than all at once. The long period of time means that by looking at Ely, we can get a sense of each of the most important medieval English architectural styles, all in one building: Romanesque (in the nave), Early English (in the presbytery), Decorated (in the tower and Lady Chapel), and Perpendicular (in the eastern chantry chapels). See the plan below.

A saint in the marshes

Ely Cathedral, sometimes referred to as “the ship of the Fens,” is a massive building rising up from the flat, marshy fenland of East Anglia. It is visible from many miles away like a lone ship on a calm sea. Ely’s history began in the seventh century, when an Anglo-Saxon princess named Æthelthryth, or Etheldreda, made a holy vow of virginity. When she was married for political reasons, she fled her husband and founded a nunnery on the Isle of Ely. In Etheldreda’s time, Ely was an island surrounded by marshes (drained later, in the seventeenth century), and the place takes its name from the eels that dwelled in these swampy waters.

Etheldreda died just seven years after founding her nunnery. When her body was translated (ceremonially moved), from its original location fourteen years later, it was found to be incorrupt and it was put into a “new” sarcophagus—actually a reused one from an old Roman settlement nearby. A cult developed around Etheldreda, who became a saint (the common name for Etheldreda is St. Audrey).

Etheldreda’s nunnery was raided by Danish invaders in 870. Whether the relics of Etheldreda survived the raid is an open question, but the author of the twelfth-century text, the Liber Eliensis (Book of Ely), detailed stories of the continued power of Etheldreda’s relics, possibly intended to suggest that they had not been destroyed. Relics were very important objects in the Middle Ages, lending prestige to the churches where they were held, and drawing pilgrims, who would come seeking miracles. The existence of Etheldreda’s relics was therefore very important for the identity of the church at Ely, where in 970, with royal patronage, the church was refounded as a Benedictine monastery.

The Romanesque (Norman) building

Though it had been the site of Christian worship for hundreds of years prior to 1082, little is known about the architecture of Ely before this date, when the first Norman abbot of Ely initiated the construction of a new church for the monastery. The foundations were laid out by a man in his 80s named Abbot Simeon who had previously been prior of the important monastic community of Winchester (in the south of England), where his brother, Walchelin, was bishop. Simeon and his brother had orchestrated a building campaign in Winchester that was still underway when Simeon came to Ely, and that in-progress church served as inspiration for much of the Ely building program.

Simeon’s building plans at Ely began in the east end with the choir and transepts. This is typical for churches, since their primary liturgical functions commonly take place in the east end of the church, oriented towards Jerusalem. This part of the church exemplifies the Romanesque style brought from Normandy after the Norman Conquest in 1066. It was completed in two different phases, which we can tell from the new decorative forms that appear on some of the capitals of the columns of the transepts, which were built later than the others.

Work on the nave was begun subsequently, and the south side was completed around 1109, when Ely was officially elevated to the status of a cathedral. Ely’s nave and transepts were some of the first spaces in England to display alternating forms of compound piers. This alternation adds visual rhythm, and diffuses the heaviness of these massive stone forms.

Like most Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, Ely’s nave elevation has three stories. The nave arcade with its alternating piers is on the ground floor. Above this is a gallery with double-light openings, or double, windowless arches, each pair set within a larger arch that mirrors the corresponding arch on the lower level. The third level is a clerestory with triplet openings. The tremendous thickness of the walls (a distinguishing feature of the Romanesque) is balanced by the proliferation of openings as one’s eyes travel upward. The viewer gets the sense that the building becomes lighter and brighter as it soars heavenward.

Late Romanesque and Early English Gothic

The west tower that tops the cathedral’s main entrance was built at the end of the twelfth century, towards the end of the Romanesque period in England.

Experiments in the Gothic style brought over from France had already begun to take hold in England—particularly at Canterbury Cathedral and the northern Cistercian monasteries. At Ely, though, the tower still exhibits round Romanesque arches instead of the pointed arches that are a hallmark of Gothic architecture.

The exterior is covered almost completely in blind arcading, an English speciality that stands in stark contrast to French medieval architecture, which prefers little extra surface decoration. Below the tower, we see a monumental entrance with blind pointed arches, which was added a bit later in the Early English Gothic style, showing how this new style was rapidly spreading across England during this time.

At the other end of the building, the presbytery was extended eastward in the 1230s and 1240s. In style, it draws from the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, completed just a decade or so earlier. With engaged colonnettes of Purbeck marble and white limestone, as well as complex rib vaults, it reflected the most fashionable architecture of the time. Then, as now, architectural styles came and went quickly, and the wealthiest and most powerful—such as the Bishop and diplomat Hugh of Northwold, who financed the new presbytery—had the means to stay current.

Eastern extensions were popular at this time to provide more room for the shrines of saints, like Thomas Becket at Canterbury Cathedral, or, at Ely, the shrine of Etheldreda. The presbytery was large enough to accommodate the many pilgrims who came to Ely to venerate the saint (and brought important income to the church and surrounding area). Having a highly-decorated space made this holy destination even more desirable.

Ely Cathedral in the Decorated Style

In 1321, a new chapel was begun north of the presbytery, which would eventually become one of the most beautiful and artistically innovative of the English Gothic period. But in the early morning hours of February 13, 1322, just as the monks were finishing their morning prayers, disaster struck. The crossing tower of the cathedral collapsed, crushing parts of the choir, and construction on the chapel had to stop.

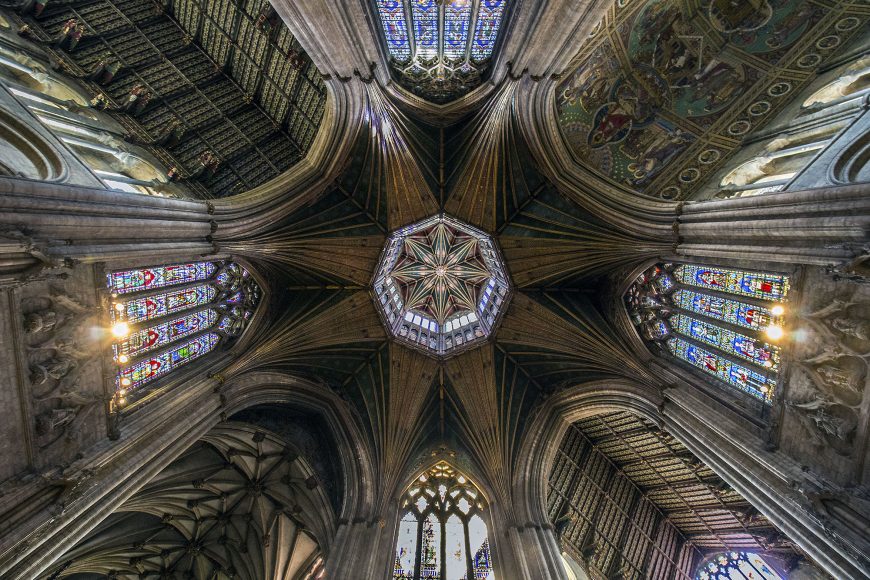

Though this collapse was devastating, it made room for one of the most remarkable structures of the English Middle Ages. Alan of Walsingham, sub-prior and sacrist of Ely, quickly initiated the building of a new tower—a tall, octagonal structure (often referred to as “the Octagon”) surmounted by a tower made of timber clad with lead. This type of tower is called a lantern because it is pierced to allow light in. Vaults with tiercerons spring from the base of the Octagon, creating a star-like effect when one looks up.

In the supporting structure below, Etheldreda was commemorated with capitals depicting scenes from her life. These include her marriage to Igfrid, and her rest on the way from Northumberland to Ely. The Octagon, from floor to the central roof boss, is 142 feet tall, the same height as the Pantheon in Rome. This correspondence may have been intentional, since the Octagon is like a Gothic version of the Pantheon’s incredible dome, and the tower above it delivers light throughout, like the opening of the Roman temple.

Once the Octagon was completed, attention was turned back to the Lady Chapel. A Lady Chapel is a space dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and this one is especially clear in its depiction of her life and miracles. The chapel, built in the Decorated Style, is rectangular, and its elevation is composed of a dado and clerestory. A series of niches encircle the room, forming the dado.

Each niche is protected with a nodding ogee canopy and ornamented with relief sculpture relating to the Virgin. It has been observed that the sculptural niches of the dado have a vulvular shape, perhaps not coincidental given that the chapel celebrates the Virgin Mary, whose chief contribution to Christian history was giving birth to Jesus.

The Lady Chapel was interrupted by the collapse of the central tower, and its progress may have been troubled again by the Black Death, which struck England in 1348. On the western side of the chapel, the nodding ogees of the dado flatten, and the diaper-work is halted. The vault fits uneasily on the chapel. Scholars suspect that some of the sculptors and masons at Ely may have fallen victim to the plague, leaving the lavish project to be completed by their less adept colleagues.

Iconoclasm in the Ely Lady Chapel

Although the Ely Lady Chapel is one of the most beautiful interiors of English medieval art, it’s also one of the most heavily destroyed. During the English Reformation, the sculptures were mutilated because religious imagery was thought to be idolatrous. The images were taken from their niches, and the colorful stained glass that would have filled the windows was destroyed. Some sculpture remains in the life of the Virgin series on the dado, but many have been stripped of their heads or more. Traces of polychromy remain, but are but a pale shadow of the formerly brilliant space.

The end of the Middle Ages

After the Black Death, a final style of the English Middle Ages emerges as the primary mode of building. This is called the Perpendicular Style because, unlike the flowing, undulating curves of the Decorated Style that preceded it, it emphasizes straight lines and vertical projections. The Perpendicular Style took hold in the second half of the fourteenth century, and continued through the remainder of the Middle Ages—almost two hundred years!

Bishop Alcock’s chantry chapel was built in the Perpendicular Style between 1488 and 1500. A chantry chapel is a space devoted to praying for an individual or a family in order to shorten their time in purgatory. Purgatory was understood to be a fiery place where souls went after death, but unlike hell, one could eventually leave purgatory after serving the required amount of time necessary for sins committed during life. A reduction of one’s sentence in purgatory could be achieved, either during life from the acquisition of indulgences, or in death if one’s loved ones or the executors of their wills prayed for them and ensured that masses were said in their honor.

Alcock is likely to have planned the chapel himself—he had been the Controller of the Royal Works and Buildings under King Henry VII. The chapel is cordoned off from the north aisle with a microarchitectural screen with statue niches that are now empty. Though this screen is extremely intricate and beautifully carved, it doesn’t quite fit in the space allotted for it. Prior to becoming bishop of Ely, Alcock had held the same post at Worcester Cathedral. It is thought that the chapel may have been planned for a large space there, but was instead jammed into tighter accommodations at Ely. Within the chapel is Alcock’s tomb, in a niche, and an altar so that Masses could be said for his soul. Alcock’s memory was also made explicit with the use of his rebus with a cock (rooster) atop a globe, and his coat of arms, three cocks.

A ship of four styles

The “ship of the Fens” is a wonderful example of the evolution of English architectural style in the Middle Ages: from Romanesque to Early English Gothic, Decorated, and Perpendicular. The people who built churches in the Middle Ages wouldn’t have thought of themselves as building in these styles, however—these are names given by historians in the nineteenth century to describe them retrospectively. The builders themselves would have thought of what they were building simply as “current.” Although Etheldreda sought refuge her marriage in the quiet, eel-filled marshes of Ely, the Middle Ages saw this site develop into a far more elaborate space than she could possibly have imagined.

an arch that is pointed rather than rounded to allow for the more efficient distribution of weight; characteristic of Gothic architecture and introduced to Europe from the Middle East; sometimes called an ogival arch or a "Gothic" arch [Art History Glossary]

vaulting with projecting stone "ribs," usually diagonal and transverse, which serve both decorative and supporting functions

the stonework supporting stained glass windows

the space behind the altar of a church

Latin, "new light," referring to the heavenly aura created in Gothic churches by the proliferation of windows, particularly with stained glass

one of the four authors of the Gospels: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John

the four books from the Christian New Testament that record the life of Jesus: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John

scale based on relative importance; the more important a figure, the larger it appears compared to those around it. Also know as hieratic scale.

from the Latin, "almond," a full-body halo in the shape of an almond

the façade and towers at the western entrance of a medieval church

a style of representation that veers from naturalism, often flattening recognizable natural forms into shapes which may or may not be recognizably figurative

a common Roman government building that became the basis for Christian church architecture

in architecture, describes a plan arranged along a single central axis, culminating at the altar

in architecture, a recess, usually semicircular, in the wall of a Roman basilica or at one end of a church, often the east end [Art History Glossary]

in church architecture, the arm that crosses the nave to produce a cruciform layout

individuals undertaking a pilgrimage

a piece of material or body part associated with a sacred event or person, and believed to have miraculous powers

in architecture, a view of a wall head-on, showing the vertical organization of its features

narrow, pointed windows

from the Latin word for eye, an opening at the top of a dome or a circular window

a heavy stone support, often larger than a column, with a wider base, and squared edges

thin columns

In Gothic architecture, an exterior structural element that carries the thrust of the nave vault over to the side aisles; the buttresses (vertical supports) and the flyers (arches that connect buttresses to the wall they support) together form the components of a flying buttress [Art History Glossary]

a painting in a handmade book