12

Travis Alber is co-founder and president of ReadSocial (a service that adds a social layer inside books and websites). Previously she founded BookGlutton.com. You can find her on Twitter at: @screenkapture.

Aaron Miller is co-founder at ReadSocial and BookGlutton, Director of Technology, Chief Engineer at NetGalley, Senior Developer at Firebrand Technologies. You can find Aaron on Twitter at: @vaporbook.

Introduction

People have always connected through books. As books enter an era in which they too can become connected, we must ask new questions about the nature of reading. We must be free to experiment with the new changing forms of books, the ways that people connect through them, and new modes of interaction. Most importantly—in a many-to-many future, where everything will be connected to everything else—we must look at the ways readers identify with each other, and how they organize meaningfully across the arbitrary divisions created by market forces. Groups of readers and their preferences are, in many ways, more relevant than any single reader out there. Often a single reader is simply a consumer, a passive audience member, whereas a grouping of consumers can be something much more powerful: a community.

Networks of Readers

Where books go, reading follows—this will always be dependable wisdom in the publishing industry. Put books in hands, and the reading will take care of itself. Publishing is not an industry that contemplates the purpose or potential of acts of communication; it is a system of production, distribution, and promotion that attempts to capitalize on latent and unpredictable demands. At its very noblest, it is a tradition of providing the very best of human thought and creativity in distilled, bespoke form. But even then, the mandate is clear: get content, package it, get it in the hands of the people you want to read it. Get them to talk about it, hopefully in favorable terms, but in the end, sell the books, just sell them so they can be read.

It’s a lofty publisher who tries to look above the bottom line to ask the question: but how should books be read? And not only to ask that question, but to understand that it’s not merely a question of hardback or paperback, or Kindle vs. Nook. It’s not merely about whether a book will be an app, or whether it will be available in foreign territories simultaneous with its U.S. release. It’s not about Garamond vs. Bembo either, or the colophon or dedication, or who you can get to write the introduction. It’s not an experiential question at all; it’s entirely metaphysical, and it might even be better to start with the question: why do people read books?

We think there is a very simple but profound answer to that question: people read books to make connections. This can be considered at a cognitive level, through simple, repetitive pattern recognition, or at a conceptual, spiritual level. Either way, the basic work of the reader’s mind is to make connections, and the basic mode of higher thought is to exist both in and out of the physical world for a bit, drawing lines between the two.

In any written work, there is a cognitive process of connection-making that makes up the act of reading itself: glyphs form letters, letters connect into words, words into phrases and sentences, sentences into paragraphs, paragraphs into a sense of semantic completion. As we read, we progress through linear rhythms of pattern recognition even as we gain higher understanding of an author’s argument, a character’s motivation, or an historical event. By connecting very small patterns together into larger ones, we connect concepts back to the real world around us, to real people and places.

The pattern-recognition part can be thought of as a linear progression, necessary grunt-work for the brain to get at the concepts. However, the tangential connections we make are the ones that matter to us—and they’re the reward that is so hard to get to for those who have trouble with the mechanical work of processing the words and sentences. We may even make many unintended connections along the way, and sometimes it’s those surprises that keep us going. From a description of a road on a summer day, we might recall a bike ride from our youth. From a listing of facts about milk, we might be startled by a sudden craving for ice cream. Perhaps during an introspective passage about spirituality, we look up from the page to see our future spouse for the first time.

A book and its patterns, and the place we sit reading it, and the person we fall in love with, can become forever tied together. It is at this level that reading interests and addicts us. We think of it as a solitary act, but it’s often the connections we make back to the real world that make it so rewarding. These connections are sometimes even more interesting when made across larger gulfs. Fake worlds, or extinct ones, can interest us more than the one we live in. We’re fascinated by fictional characters when they mimic or reflect real personalities. Even the most outlandish science fiction[1] can be interesting in this way, because of the allegory, or the grand sense of scale that crisply dramatizes contemporary issues, or the parallels we can make between even the most alien worlds and our own. It’s these very large, meaningful connections that are the ultimate goal of reading. It’s the understanding we gain, or at least feel we gain, about the world we live in, and the people we share it with, that are the deepest connections we make when we read. In that sense, it is entirely social.

Understanding this, then, what does it mean to go back and consider the question: how should books be read? And not only that, but how should they be read, given the context they’re moving into?

It’s not simply that books have become “digital.” We find ourselves reading in a new context that is not just about carrying our entire personal libraries with us or about realizing a dictionary just works better being part of every book. It’s not just about the constellation of tweets, videos, podcasts, blog posts, discussion threads, and YouTube videos that now surround a publication, or about how we read our books in whatever situation we want—possibly on the same device that maps the nearest freeway entrance, possibly while texting each other about dinner.

It’s about the context of a new medium, the Web, which is inheriting books. It’s a medium, it seems, that better embodies the idea of making connections between things, places, people, and events than any other medium that has preceded it. In its meteoric growth, it seems to have captured our interest with this very quality. On the Web, we call connections links,[2] of course, but they are not much different conceptually from the kinds of links we make in our own minds while we read. What does it mean that books are moving into this medium, where connections are part of its very fabric?

Getting books along that path is the business of web designers and developers who are creating the next generation of books and book interfaces, and of the entrepreneurs who are building the next wave of distribution and communication channels for them. Perhaps books will always be called “books,” but what they actually are might change, so that they could also be called “web bindings,” a new kind of web page collection. In any case, they will all necessarily be linked to each other in various ways, just as most everything on the Web is.

But before that can happen, we have to solve a problem. When people read digital books today, they are engaging in an activity that is all about connections, on a device that can potentially make those connections, but they’re being prevented from making them. So again, instead of looking at the question of how people should be reading, we’ve so far only addressed the question of how to get books to them. Unfortunately, instead of delivering those books in silos of disconnected paper, we’ve delivered them in disconnected mechanical devices. Instead of going directly to the Web, we’re taking a roundabout way, and the interests of readers, and the future of reading itself, suffer terribly.

That books are inherently social is not an undisputed point. In most cases when it’s conceded, it’s still argued that the act of reading them is still not in any way social. This line of argument claims first that reading is a solitary activity. It is done alone, has always been, and if the future holds something different, it is so far away that we should not distract ourselves with thinking about it.

This argument is reductive in three destructive ways: books, social, and reading are each oversimplifications of what we actually refer to with those words. They are dangerous to combine in any argument or theory. In fact, reading may be solitary, sometimes, but it’s not necessarily solitary. When it’s done in solitude, meaning without the help of others, or in physical and social isolation, it is often done so for the purpose of understanding or entertainment. To understand something, our brains must concentrate, and exclusion is necessary for that. And to enjoy something, we must allow it to captivate our imagination and senses, and this is a solipsistic activity. So in both of those cases, reading must be solitary.

But we all know, if we’ve ever learned to read with the help of a parent, or learned to analyze literature with a professor and group of peers, or discussed the latest Twilight book in a fan group, that much understanding and fun can occur around a book after we’ve had that first solitary connection to it. And in fact, the varieties of fun and understanding out there are far more diverse than the solitary ways in which we initially engage with our favorite books. Thus, much of the value in books lies in discovering that they are shared experiences, and seeing the spectrum of individual connections to them.

It’s in that spectrum that the Web offers so much for the medium of the book. As a network of people and communities, it is also a network of voracious readers. As an extremely versatile and evolving visual medium for the consumption of content, it can nurture the solitary, experiential nature of reading. And as a network for other kinds of media, for social interaction, and for sharing, it can enhance the communal, educational, and analytical aspects of our experiences with books.

We Are All Book Gluttons

In 2005, despite the rise of social networking, digital books on the Web were limited to free editions of public domain works, loaded as a single, scrolling text file. The reading interface usually consisted of the browser’s own scroll bars, the ability to share the URL of the book, and the customary contextual controls (right click for a menu of things you could do with the page or a range of text). As an experience, reading these books online was, in all cases, limited to what the browser itself offered.

There was no way to discuss the book in context, meaning as you looked at its pages. To us, it appeared as if all the people who cared about books online had casually flung them there in their rawest state. A few projects attempted to present them with sophistication, but by and large, it seemed none of the projects had put the kind of thought into creating those online forms that a web designer, developer, or information architect would have developed. And meanwhile, the rest of the Web, including other forms of older media like audio and video, was benefiting from the careful attention of a decade of thought about reflowable layout, digital typography, visual design, and user experience.

There were very few online reading options for books then, and those that existed weren’t benefiting at all from being on the Web. To us, it seemed that the Web offered endless possibilities for a new kind of reading experience, something that was not possible offline, and not possible with printed books, but truly native to the way people already used the Web. An idea emerged, over the proverbial cocktail napkin and a round of bourbon, at a local spot in Champaign, Illinois. The basic concept was a web-based reading system that could connect people anywhere and let them discuss parts of a book as they looked at its pages together. It would preserve many things we loved about books, such as the importance of page layout, margins, readable type, but it would add what we liked about the Web: connections to other readers, a sense of communal experience, a window into other people’s reactions, the chance to respond or add our own thoughts.

Being web developers, we did what web developers do when something doesn’t exist and they have some time: we built it. In October of 2006, we began wireframing what would come to be called BookGlutton, a site that aggregated books and allowed unlimited consumption of them, with others, all in the browser. At the time, the social web that we know today was just taking hold. MySpace was the dominant social network, with Orkut and Friendster following. Facebook had opened to non-students[3] in September 2006, and Twitter had been founded just two months earlier, in July 2006.

In January of 2008, we launched the first public version of BookGlutton.com.[4] At the time, no other website, service, or device combined access to book people with access to book content. Sites like LibraryThing, Goodreads, and Shelfari were focused squarely on giving people ways to share and discover book metadata, not book content. Each of these sites appealed to a different type of user: LibraryThing had a number of specific ways to track metadata, especially by edition; Goodreads was focused on short book reviews created by its users; and Shelfari, which was purchased by Amazon within six months of launching, was working towards a slick interface and a focus on finding other people who had read the same book. Many serious readers belonged to all three sites at some point (membership was free), but there was considerable overlap, and users generally picked one site that focused on a preferred trait. These sites had plenty of social components, but no content.

On the content side, Project Gutenberg, Manybooks, Feedbooks, and Amazon were all about downloading books to read offline. Gutenberg was the oldest way to get books and had always been free; Manybooks focused on providing as many formats as possible; while Feedbooks provided high-quality editions for the new mobile devices popping up everywhere. You could jump off from many of these sites to buy content, but much of what you could buy was still printed material. The ebook world was showing signs that powerful forces were about to make it grow fast, but it was still in its infancy in terms of what was available. The iPhone was the unexpected success in terms of providing a reading experience. An app called Stanza had managed to aggregate free books from the Web and allow users to flip through pages by swiping them back and forth; the high resolution of the screen made up for its small size, and the combined result was a very tactile, reflowable reading experience with plenty of content choices. On the dedicated device side, the first Kindle arrived in November 2007 and, along with the Sony Reader, set the standard for e-ink devices.

In the midst of the content distributors, the device makers, and the social book networks, BookGlutton sparked an interest in the notion of social reading: the act of reading while connected to other people, or the philosophy of reading as a connected activity, not an isolated one. It was a space that no product or service had entered yet, and it revealed something often overlooked or forgotten about books—that they have always been social objects. They have always provoked reaction, social change, conversation, dogma. They exist as educational tools, as propaganda, as centerpieces to entire religions. They are passed down in families, passed along as vehicles of knowledge, human history, scientific thought, and philosophy. They have provoked wars, helped broker peace, and been burned out of fear of their social influence. They contain our imaginations and our histories. They spark debates and influence law; they entertain audiences and inspire them to create new entertainments. Many books come down to us through long histories of oral tradition; others have been compiled meticulously over time through processes of committees and organizations. Books are vehicles for something much older than their containers, and that legacy is undeniably the larger society’s record of its own interactions.

We think that an important shift is happening now, in the way that we think of books, which is to say that the Web is beginning to unlock some of the latent potential of them, potential that has been locked not just by their physical nature, but by their long history of commodification in physical form. The Web is quickly antiquating the notion that a book is a physical object you buy, read in solitude, and never think of again. A book is now an image on your profile, connecting you to anyone else with that image. It’s an organizing topic for a virtual group or a badge on your blog, a vessel for topical conversation, a record of your education. It’s now tweetable from a dozen different virtual places. Now, as books not only go digital, but move online, the natural dialog that already exists around them (and always has) can be amplified in ways we could never before imagine.

You can see evidence of this potential even in their commodification. The educational textbook market in the U.S. last year was $10 billion. That is a fair amount of trade happening on books that are intended for a shared, social context (classrooms and universities), with an explicit social ideal as a goal (furthering the knowledge of our young and preparing them to give back to society).

You can see it even when looking at the blockbuster titles from big publishing houses. Top sellers are often celebrities, politicians, or other individuals with strong social influence. The social network effects of such titles can be measured in terms of fan groups, website memberships and activity, Facebook likes, Twitter followers, etc. And it’s not just that books have suddenly become social—they’ve always been social—it’s that we’re seeing a revolution in what the Web can do for anything that’s already inherently social. The notion of gluttony—a concept that almost never has any positive social connotations—bears exception when it is applied to lovers of books, who proudly proclaim themselves avid devourers of these social viands. The Web itself is a glut of things, books included, and we are all social consumers of that abundance. Not only does it never end—it always grows in size. Even an infinity of gluttony won’t consume it all. We are all destined to be book gluttons, in the most positive sense of the term.

Group Reading in a Browser

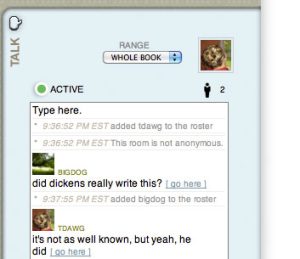

BookGlutton[5] is a destination, a reading system, a free catalog of books, and a community. It allows people to form groups and connections just as many social networks do. What distinguishes it is that books are read while on the site, right in the browser. Users create a group around a book, invite their friends, and comment on each paragraph. They can also see and respond to comments that have been left by others. The comments are asynchronous and grow over time, creating an additional layer of annotation content on top of the book. Readers can also join a chat room for the book, discussing it chapter by chapter.

We have always believed the web browser to be a better tool for reading digital text than any other application or device. This is a matter of heated debate, and is more or less defensible by degrees for different kinds of content, on different sites, at different times in recent history, but overall, we have believed in and encouraged the trend toward the browser eventually becoming the perfect reading environment for any digital content, on any platform. Recent advances have shown this trend to be accelerating, especially with the proliferation of tablets, where the browsing experience is more central. Traditional drawbacks to browser-based reading are all being addressed in rapid fashion on many fronts, faster than we’ve seen previously. The bigger historical complaints—poor typography, no offline capability, no paginated views and too many distractions—have been, or are being, addressed, via combinations of new standards and open source efforts, and most browsers now allow offline reading, third-party font support, and pagination. Services like Readability and Instapaper are aimed at reducing clutter, ads, and other distractions to reading content on the Web, and now there are many browser-based reading systems for books that focus on good typography and ease-of-use, whereas in 2006, there were none.

It would be easy to say now that it was a foregone conclusion that books would wind up in browsers. But at the time that BookGlutton was released, there was much skepticism around the idea, mainly for the historical complaints mentioned above. But it was not long before a viable path became clear, and that it was not only viable but probable. As Amazon’s Kindle strategy[6] was revealed to be a multi-device, multi-platform strategy, and as Apple entered the race, not only with a tablet, but with a competing ebook application, and as Google released their own e-book store, built entirely around a browser-based reading system, and Amazon followed that with their own browser-based Kindle application, it became painfully evident for smaller players in the space that the browser would definitely be playing a central role in our future consumption of digital books.[7] Furthering that, and perhaps stoking for an inferno, Amazon launched the Kindle Fire, a tablet clearly meant to rival the iPad more in its potential for media sales than its novelty as a device. Finally, as if to hammer home the idea of books becoming native web citizens, the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF[8]) in 2011 released their specification for EPUB 3, and by doing so confirmed a very close alignment with HTML 5,[9] the bleeding edge version of the markup language that makes up most documents on the Web.

Despite the stiff competition for readers, BookGlutton has gathered over 30,000 members and over 4,000 groups, of which some 300 are classrooms studying public domain classics. Anyone can add EPUB books to their group, and any book may be shared with any other user in the network. The core catalog, about 700 books at the outset, has since expanded to about 5,000. One of the draws is still the unique combination of virtual book groups with an in-browser reading experience. It is the living example of what has become known as “social reading.”

Our goal in building a reading system was to address two modes of reading: the solitary mode, which required focus, concentration, and lack of distractions, and the social mode, in which interactions with the text and with other people are key requirements. In both, we wanted the book itself to be a central, dominant component. Initially we floated the social features on top of the page in a dialog that the user could drag around. This allowed for a narrower screen, but it also obscured the content (Figure 1). At the time it seemed unforgivable, but has since become an acceptable inconvenience on most mobile devices. By launch we had redesigned for a laptop screen and added two horizontal sliding bars that opened and closed, to hide and show social content (Figure 2).

BookGlutton’s reading system tracks each user’s location inside a book, relative to each other and the content points of the book, as a social map, the way you might want to know the locations of your friends at a party. The left side chat bar featured a “proximity factor” to provide a measure of the relevance of each instant message to the current user’s reading location: for context-specific conversations and for avoiding spoilers.

Although BookGlutton offers multiple types of communication, asynchronous is more popular. To attach comments to a paragraph, the user clicks on a paragraph to select it. The commenting bar slides open, and the user can type in a note. Comments may be public to the group or private. Some readers make private comments that are strictly word definitions, while others use the public comments to ask questions or react to passages. All comments also have a reply button. Responses are non-nested, for the sake of simplicity.

Reading a comment is easy—activity on a paragraph is denoted by a small red asterisk in the margin of the book.

Readers can manually slide open the Comment Bar and see where the comments in the book have been placed (clicking on one jumps users to that page of the book). There could be thousands of comments on a paragraph at any one time, but only those relevant to a particular group appear. Moreover, any paragraph can have multiple comments attached to it, with multiple replies to each one, which can lead to a lot of data living on top of a book.

One of the salient truths that has arisen from operating and studying BookGlutton as a website and community is one that seems to be gaining importance all across the social web: the importance of groups in fostering social interaction, especially groups that have real-world grounding.

Groups form all the time on social websites, of course, but they can be divided into two key types. The first is an assortment of strangers who simply gather around something—a topic, a meme, a product, a celebrity, a favorite food, a news article. The bond between these people is usually weak. When one invites another to take some action, the likelihood of that action happening is fairly slim.

The second type of group is a group of people who know each other in real life. The likelihood of one member inciting another to take some action is fairly high. In the early days of the BookGlutton site, when a member of a group invited another to join the group, it was usually because they knew them in some physical setting, and the conversion rate was nearly 80 percent for those kinds of invitations. The stronger the real-world bonds across virtual groups, the better the interaction and engagement will be.

It would seem to be self-evident, when stated this way, but early efforts at social networking online largely ignored the importance of groups. The exception was the network with the most velocity on its growth rates. The initial viral growth of Facebook owed a lot to the method of deployment: one college campus at a time. Since every student on a campus could be verified by virtue of owning an email address with that institution’s .edu domain, there was a strong parity between the real world bonds and the virtual ones. This created extremely high conversion rates, and high-velocity growth.

Reading, as a social activity, is no different from any other social activity in this regard. The interactions between readers of a book, the engagement with the book itself, and the bond among group members are all significantly enhanced by some grounding in a real-world group unit, whether it’s a classroom, a college, a family, or a church.

With BookGlutton, we did not initially realize that the expectations for a book-related site were geared powerfully toward searching for a title, finding it, downloading it, and reading it somewhere else. Those users quickly became disappointed, because that was not the system that we had built. We had built a group reading system, meant for shared experiences of a text, group annotation, and a sense of community around the act of reading and annotation. It was ideal for people who knew that learning about a book is best done in a group setting, or for people long distances from each other who wanted to let reading the same book draw them closer together. We realized that we were not emphasizing the group aspect of it enough. We were seeing many users come and stay, and invariably they were the users who had come seeking that group experience around a book.

Now, when a user registers on BookGlutton, a group is automatically created for him or her. Each group has an associated reading list. It is then up to the user to invite friends to the group or add more content to the reading list. Users can have many groups, the core of which are personal connections. Many are still based around a book or a concept, although we still see the most successful groups having a corollary offline.

The center of group activity is the Group Page. Users can jump into the current book from this page, message all users in the group, or leave a message on the group wall. Any user can also change the current book for the group’s reading list. Multiple methods of communication meet different needs.

Content on BookGlutton comes from a variety of sources: free public domain titles, free books from Feedbooks and Girlebooks, excerpts from Random House and McGraw-Hill, original publications by BookGlutton, and for-sale books from O’Reilly and Holarts Books. BookGlutton also offers an HTML to EPUB converter for writers who need to get their content into the EPUB format for discussion on BookGlutton.

Much activity on BookGlutton centered around excerpts, lower-cost and free content. Major authors added comments to some of their book excerpts, and readers responded. New fiction writers uploaded their work and got feedback. English as a Second Language (ESL) groups used it to learn context and vocabulary. Around three-hundred school systems and universities began to use it as an online component of their classrooms.

These uses taught us some valuable information about how groups interact and how offline and online associations influenced each other. At one time 79% of all group invites were accepted, and 20% of new users started their own additional group. We were seeing things we hadn’t expected and would have never predicted. But the biggest realization came after a full year of having a book store. We were running three separate businesses: distributing content, promoting content, and making content social. It was this last business that interested us. No one seemed to think it was even a business, and we weren’t sure yet either, but we did know it would be a big aspect of what books became.

The Read Social Mantra

By observing BookGlutton over a four-year period and experimenting with other, smaller proof-of-concepts, we came to several realizations about how we should try to move things forward. The first was that the content network, the reading platform, and the social layer are three distinct businesses. Each of the three specializations requires its own technical considerations, strategy, and business development plan. A small company or group of people cannot handle all of the challenges of each of those businesses combined. Even large companies falter when they attempt to reach outside their realm of expertise in one of those domains.

Secondly, the social layer, which we call the group layer, is new, and as such it requires dedicated thought, experimentation, and collaboration. To create experiences that “just work,” every user interface consideration makes a difference: from the steps involved in posting a public comment, to how groups are defined, to how comments are managed long term. Moreover, as the user base becomes more comfortable with social networking and how it’s integrated into systems, expectations change. It is extremely difficult to get it right the first time. Iteration is key. This is especially difficult for large companies with a close eye on profitability, as it might take several iterations to increase conversion rates.

Another thing we noticed: while many people might be casually interested in browsing a stranger’s comments on a book, very few will want to engage with those comments. In a group, on the other hand, there is often some top-down structure, or an assignment or other group goal. This makes interaction important and connections trusted. Trusted connections facilitate more open communication and engagement with the book.

We learned that for books, asynchronous is better than synchronous. This was contrary to what we expected. The Web has become more “real time,” and we had assumed people would want to announce each time they’ve opened a book. In fact, we used Twitter to allow people to do just that, but it wasn’t what they really wanted. Instead we found that while a rapid-fire, real time discussion is occasionally valuable, books are different. Most books are a longer-term commitment than other media and are consumed at a slower pace. People dip in and out of them. They are grazed on, ruminated on. Some require great study and thought before their messages are clear to us. They are, in many ways, asynchronous. As a result, it’s rare that readers will meet at the same point at the same time. Our conclusion: the 24 hour, global nature of the Internet makes asynchronous communication the preferred mode for long form media.

Based on these realizations, we built a new system, ReadSocial, which focuses exclusively on how to connect people across reading systems. Instead of offering a destination (like a website), with content (like an ebook), ReadSocial offers all content owners a way to add group-based, asynchronous commenting to what they’ve already built. From ReadSocial.net any content owner (blog owners, small ebook publishers, iPad magazine apps, ebook reading systems) can choose a usage tier and get a bit of code that ties into the ReadSocial system. This will allow their users to create groups, attach comments, images, and links, and respond to comments by others.

ReadSocial uses open groups, tracked via hashtags (for example #janeaustin or #peoria_readers or #mrs_james_hour2). Anyone can read posts to any group (if they know the group tag). Users are identified via OAuth, which is the mechanism used by Twitter and many other social networks. It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s one widely used solution to the problem of accurately identifying users across systems. It encourages the use of aliases—the same user might be able to OAuth themselves from a different network each time, but the network they use is seen as an authority on who they are. In this way, other users can at least have some reassurance that the joe_schmoe they know on Twitter is really validated by Twitter, even though he’s posting on ReadSocial.

They may also see a joe_schmoe from Wordnik and know that it’s the same Joe Schmoe they know, but if they see a joe_schmoe from evilnet.unknowndomain.com, they can steer clear. It’s not the solution everyone is looking for, but it’s working for many services now, and it solves one problem that ReadSocial must solve: how to ensure that offline bonds are driving online interaction. Offline users might not all know each other from Twitter, and that’s fine for ReadSocial. Likewise, they might not all buy books from Amazon and read them on Kindles, and that’s fine too. A person can read and post with the same group tag on any system that uses ReadSocial, with any content, using any OAuthority as their identity network.

Using open groups and group tags, an individual can read the same paragraph or article and “group surf,” getting different commentary with every change in group context. Moreover, any reading system can pull in new and changing content immediately. For example, the #ows group wants to comment on news. Members can go to any site, iPad app, blog, or other content channel with ReadSocial installed. If the same article is syndicated across all of these places, then #ows comments will appear in the margin. A user may read or respond to a comment or post their own.

Anyone can build a client interface for the ReadSocial service. If a company wants a completely branded experience with additional features (such as recommended groups or book recommendations), it can build on top of the API. For companies that just want to get going right out of the box there are the open source client libraries for web and iPad (which include the visual components for the interface that that users need to create groups and manage comments).

Conclusion

We’re now at least six years into a new age of social reading. Community interaction is a natural extension of the Web, and we will continue to see more sophisticated integration of features that have their roots in the Internet. The Web will be our guide. In working through the design and development of BookGlutton and ReadSocial, we made some key discoveries about social reading:

- Groups are not necessarily groups of people, but topical filters for conversation. It’s not necessary to think about a group made up of people accepting invitations; it can also be made up of concepts and ideas. A group can use a topic as an organizing force. We see hash tags used this way on Twitter.

- Groups are often related to real-world communities, events, and networks. The more off-line interaction a group has, the stronger the ties; offline user groups transcend siloed technology purchases. The strongest web-based products have a connection to the real world. ReadSocial respects those bonds, not the ones between vendor and consumer, by enabling open notes that cross silos.

- People are used to commenting publicly on things that are public, moreover some things are inherently public (i.e., an untweeted tweet is not a tweet at all). As long as the user is aware of the context, an open system works. Closed systems and systems with complex levels of authentication and privileges are desirable too, but at this point in time, it may be better to start in earnest on solving the problems that we’re ready to solve.

- Location/passage identification is going to be up to reading systems, standards groups, and content publishers.

- Interfaces and systems for storage, sorting, searching, and grouping of shared items will be the expertise of the social layer. To create trust with your users, it is important to be straightforward and clear about who owns comments, where they go, and who can see them. Like web search, entire businesses will be built around these simple concepts of filtering and interfacing with social reading data.

- Getting network effects is a dedicated task (a.k.a. building good social networks is really hard). ReadSocial doesn’t invent its own network, it builds on top of existing ones.

- The conversation layer is where publishers and providers of reading systems tend to get lost, as it’s often at cross-purposes for them. Specializing in the overlay interface creates distinct value.

Even in Web-based systems there will be many approaches. One would be to offer a fully integrated solution of reading system, book, and community from a single source. BookGlutton gives us insight into benefits and drawbacks of this type of system. If a company owns the content and has the technical savvy to run the reading system and group management, it can be a powerful experience. It is more in-line with traditional group invites (users invite others via email), and the level of control of the group and reading system can offer a heavily personalized experience. Systems like this are great for gaining metrics, and they offer a wide-range of possibilities for customized activities. Of course, drawbacks stem from the same level of control. Successfully managing a system is more complex—and the focus on community is often lost in the quest for a flexible reading system and adequate content.

ReadSocial offers a different approach—the API. It offers the ability to quickly add a social interface and share content with other systems. The ability for networks to pull in content from other networks (and push it out) can be powerful. The system works best with the greatest network effects; like most social systems it gains value the more it is used. The open group tag allows for content-based groups as well as people-based groups, and it works easily with an offline component, which we’ve found is a major driving force.

We know that some of this is guesswork. OK, a lot of it is guesswork. But the important thing is not to dismiss what’s actually going on right now. People are reading differently already. It’s the readers who are determining the future, not the large corporations we think are dictating the way people read. Give them tools to read the way they want to, and watch how they do it, and learn from what you observe. Iterate on that. And keep it simple while you do. If a system looks too hard to use or seems too hard to understand, no one will try, and you won’t learn anything. The most exciting part of what’s happening now is that there are a thousand possibilities. We might not have a fraction of the time to do them all, but there are millions of other people out there getting interested in this future. Let’s share ideas and make the future happen sooner.

Give the author feedback & add your comments about this chapter on the web: https://book.pressbooks.com/chapter/above-the-silos-travis-alber-aaron-miller

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Foundation_series ↵

- http://www.wordnik.com/words/hyperlink ↵

- http://tcrn.ch/9n4WR8 ↵

- http://www.bookglutton.com ↵

- http://www.bookglutton.com ↵

- http://www.teleread.com/uncategorized/amazons-long-play/ ↵

- http://bit.ly/MDncyL ↵

- http://idpf.org/ ↵

- http://www.w3.org/TR/html5/" target="_blank ↵