21

Peter Collingridge (@gunzalis) is co-founder of Enhanced Editions and MD of Apt Studio. He recently joined Safari Books Online.

IT’S ALL IN THE DATA…

At least, that’s what we realized a year into our first startup. It was in early 2010 when we looked into the analytics from our enhanced ebook apps, and recognized we had stumbled upon a goldmine—a voyeuristic peek into the habits of when and how a reader reads.

In 2008, I had co-founded a company called Enhanced Editions, with the humble goal of making the ebook that the iPhone deserved. By mid 2010, it was clear that we weren’t going to make it as a business, and we changed course, hard, to capturing as much data about readers as possible. It wasn’t a random pivot, but a change of direction absolutely informed by our failure to sell enough apps.

Our first app (Bunny Munro, by Nick Cave) had succeeded in capturing the imagination of readers, publishers, authors, and journalists around the world. It earned us enough downloads, sales, and column-inches to make us actually believe that we had invented the first truly digital book.

However, try as hard as we might, this initial hubris gradually wore off as we conclusively failed to convert our initial success into a sustainable business.

Bunny reimagined the ebook as a multimedia experience: we synchronized the audiobook (read by its rock-star author) to the ebook, which was itself designed with the utmost typographical care that the iPhone allowed. We included 13 videos of Nick Cave reading, carefully filmed against projected backdrops. We produced a live news feed of exclusive material, and the audiobook included a soundtrack written and performed by Nick, timed to key points in the narrative.

Possibly my favorite piece of coverage described the app as “the moment digital publishing came of age.” Unfortunately, we realized (too late) that one of the major drawbacks of the business was that it didn’t solve a burning problem for our customers. This is something any VC (and at least some MBAs) will tell you is vital to a startup’s success.

In fact, it was unclear to us who our customers were—publishers, authors, or readers. We aimed first at readers. Unfortunately, none of them was waking up screaming in the middle of the night, “I need audiobooks synchronized to text and the ability to watch videos of my favorite author alongside beautiful typography.”

Any technical or user experience achievements we had made were in stark contrast to our commercial achievements, which were in turn out of sync with what our multiple data points were telling us.

Our failure to sell enough of the apps didn’t line up with what our analytics were telling us from within the apps. People spent a huge amount of time reading and listening. The audio sync was by far our most popular feature (with video surprisingly low on people’s priorities), and people were using the app between 50 and 200 times per month, for around an hour each time.

So if the apps weren’t in themselves lame, this suggested a failure elsewhere–in marketing and promotion. And as we dug deeper it became clear that connecting digital products to their target audiences required a whole new set of capabilities that publishers simply don’t have.

Here was a real problem: what does good, successful promotion look like as publishing changes from print to digital and from B2B to B2C? This seemed like a real problem that we could sink our teeth into. It also had a steady supply of very well-defined customers (publishers! agents-turned-publishers! authors! self-published authors!).

Now that anyone can create and distribute a book to a global audience of millions in a matter of seconds, successful marketing is the single activity that will define institutional publishing. Indeed, it will provide the differentiation publishers need to justify their place in the food chain in the 21st century.

However, book marketing is broken. It is not evolving at the rapid speed of other parts of the industry. Shockingly, many campaigns look identical to those planned ten or more years ago, relying on PR and big-budget poster campaigns.

Why do campaigns stick so rigidly to this formula? There is not—nor has there ever been—any empirical understanding of which combination of marketing strategy and tactics works. Currently, publishers might spend between 5 and 10 percent of their revenues on merely hopeful marketing, with little idea of what works and what doesn’t. There is very little after-the-fact analysis.

“It’s difficult to determine what marketing strategies helped, hurt or were just a waste of time.” –WIRED author David Wolman, quoted in Nieman Report Winter 2011, on promoting his Kindle Single.

At Enhanced Editions, we firmly believe the answer to this problem lies in what we call “little data”—the methodical analysis of campaigns, in combination with more agile marketing techniques. By focusing on “little data,” publishing can dramatically improve its return on marketing investment.

“When it comes to the really important decisions, data trumps intuition every time.” –Jeff Bezos, CEO Amazon

Publishing houses still make their marketing decisions based largely on gut feel rather than on data. New entrants to the publishing ecosystem—Amazon, Apple, and Google among them—all employ data-driven decision-making approaches. In the same way that you wouldn’t consider launching a website without analytics, the same should be true of a digital book: ebooks are, in effect, just websites.

Making a significant change in how publishers make marketing decisions will not be easy. The data that is currently available to publishers is becoming increasingly irrelevant to an ever more digital marketplace.

In the United Kingdom, where Enhanced Editions is based, Nielsen sales data is provided weekly, and gives no insight into ebook sales. It does not break down sales by day or by hour or by location. The absence of specific data on sales makes it impossible to separate the impact of one activity from another in the course of the week’s sales.

At the same time, Amazon rankings have become an industry standard proxy for performance. When we researched the market, we heard many stories of publishers obsessively refreshing their product page during a day to help drive telling variations in sales rank. Telling into what was less clear. The ranking itself was seen as a goal, rather than one measured against a particular activity or tactic.

So we started with a belief that a data-driven understanding of consumer behavior is fundamental to the future of the publishing industry. After researching how publishers were quantifying the new world (answer: barely more than the refresh button on a browser), we decided to stop making apps, focusing instead on building Bookseer, a market-intelligence service for books.

Bookseer currently captures the “little data” that are a by-product of other activities. The real-time data “exhaust” of the Web, combined with details of promotional activities provided by the publisher, lets Bookseer build a systematic picture of the variations in performance across thousands of titles.

Bookseer collects as much information as possible about these books. The data it captures can include:

- price on Amazon

- hourly sales rank

- print and ebook sales data (uploaded by the publisher)

- what is being said about a book or an author in the media, across social media and on the wider Web

- marketing promotions

- the makeup of bestseller charts and so on

We collect this data in a variety of ways, and we do it all in real-time. As long as we can identify significant events—media coverage, a tweet, a price change, a review—at a specific moment in time, we can measure the effect of that event on sales. In doing this, we can clearly show the individual activities that are directly influencing sales, and of course, the ones that are not.

To share a couple of examples: The first is a big-budget marketing campaign from the UK.

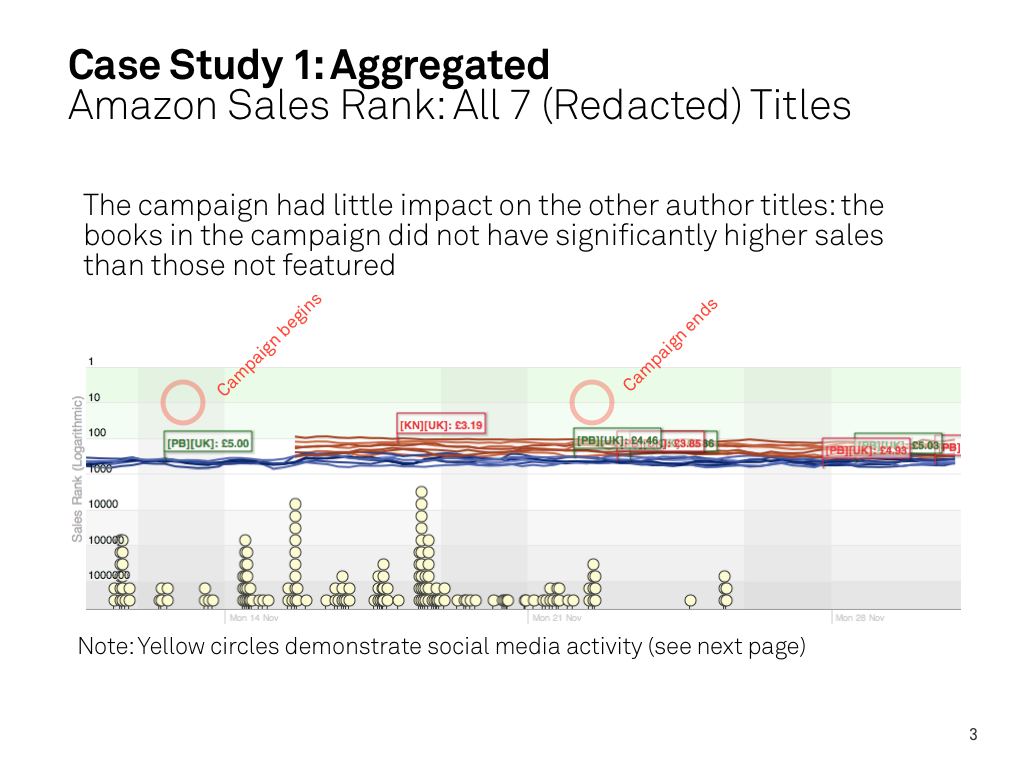

We tracked all even titles written by a well-known author, in digital and print format, in advance of a nationwide poster campaign (with a social media component) that promoted three of the seven titles. The remaining four titles were tracked as a “control” to measure baseline performance on the non-promoted titles. We also tracked mentions of the author name and the social media keyword promoted on the posters. Given their prime locations, these posters probably cost between of £75–£100,000.

We tried to close many of the open loops in publishing data. As well as tracking Amazon sales rank, price changes, and social media activity, we included Nielsen sales so we could see how closely Amazon sales rank and actual sales are correlated. This approach helped frame all the activity in hard commercial numbers.

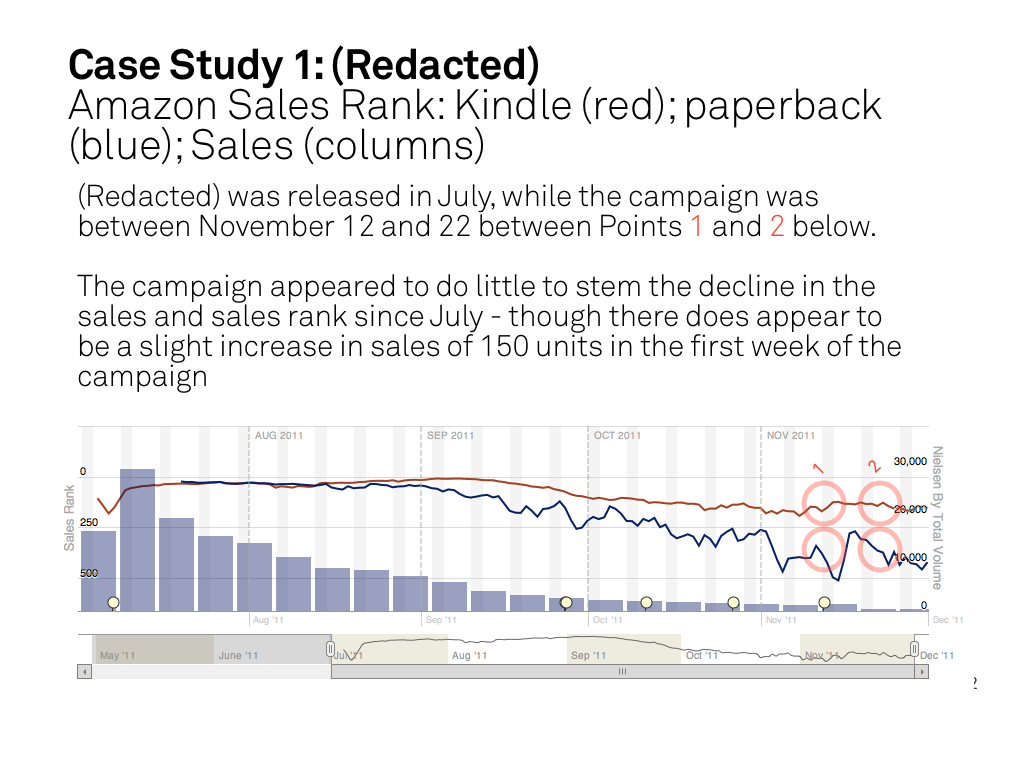

On the above chart, the navy blue lines at the top represent the hourly sales rank of the paperback. Because it is incrementally harder to get higher up the chart, the scale is logarithmic, with the top section reflecting the rankings between 1 and 10. Kindle and print charts have their own rankings. The blue bars are the actual paperback sales through Nielsen, and the red lines are the Kindle sales rank.

The first circle (1) shows when the campaign started, and the second circle (2) shows when it ended. The poster campaign made very little impact on sales, which were already declining. If one was generous, one could attribute a slight increase in actual Nielsen sales (of around 150 copies), and a slight stemming of the downward trend of Amazon sales rank during the campaign, but the impact isn’t exactly jumping off the chart.

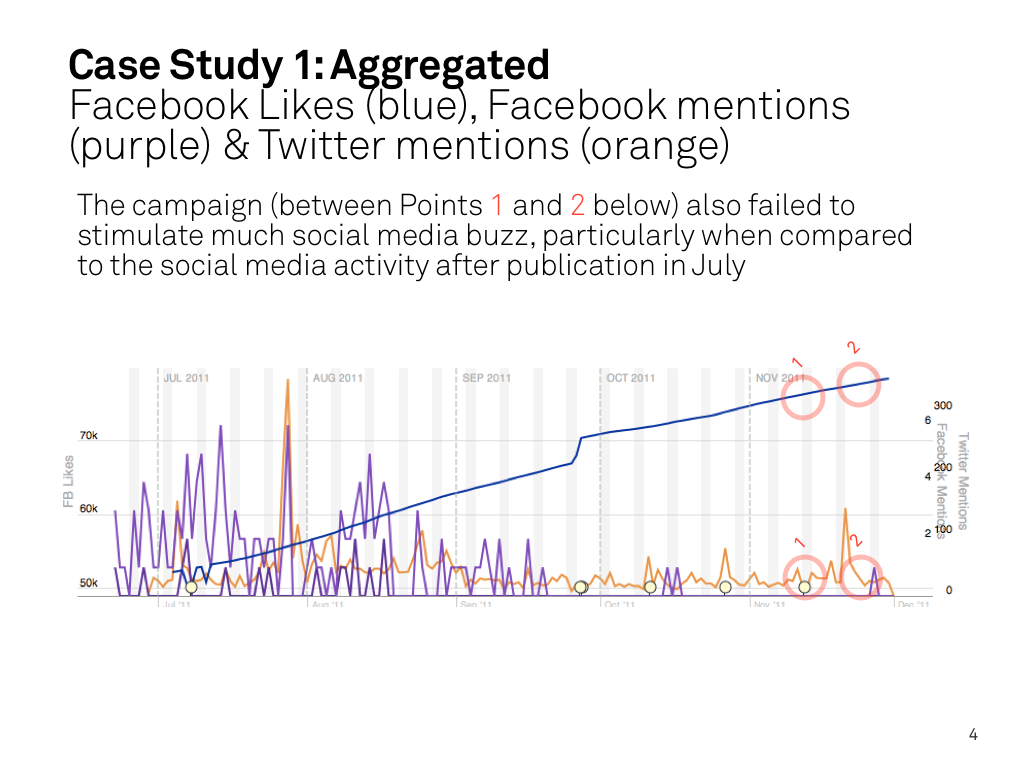

This second chart shows the social media metrics. Here, the blue line is the number of Facebook “fans” for the author, which is steadily climbing, but which remains unaffected by the campaign, again shown between point 1 and point 2. There is a spike in the instances of the Twitter hashtag promoted on the posters, although the total number of tweets generated was 37. You can make up your own mind as to whether this poster campaign was worth the spend.

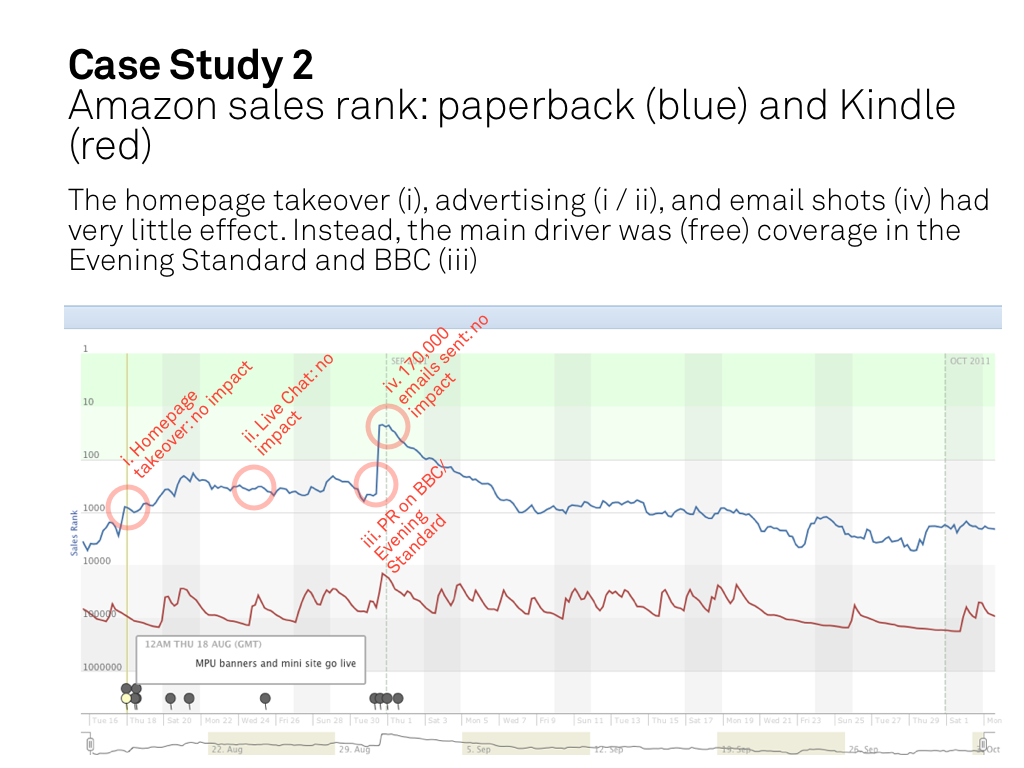

A second case study also highlights the risks of big-budget print marketing as a vehicle to drive book sales. This data collected for a “chick-lit” title published in the UK, with a heavily digital launch spend focus. Ads were placed on YouTube, and a high-traffic community website (with a strong demographic crossover with the book) was targeted. All advertising space on the website was bought, pointing to the Amazon product page.

Furthermore, an author livechat and two direct emails to site subscribers—over 350,000 of them—were secured. Estimates are that this required an investment between £30,000 and £50,000.

On Bookseer we can see when:

- Advertising goes live on site

- Live chat takes place

- The author appeared on BBC Breakfast TV and was interviewed in the Evening Standard

- Two emails were sent to groups of 175,000 subscribers

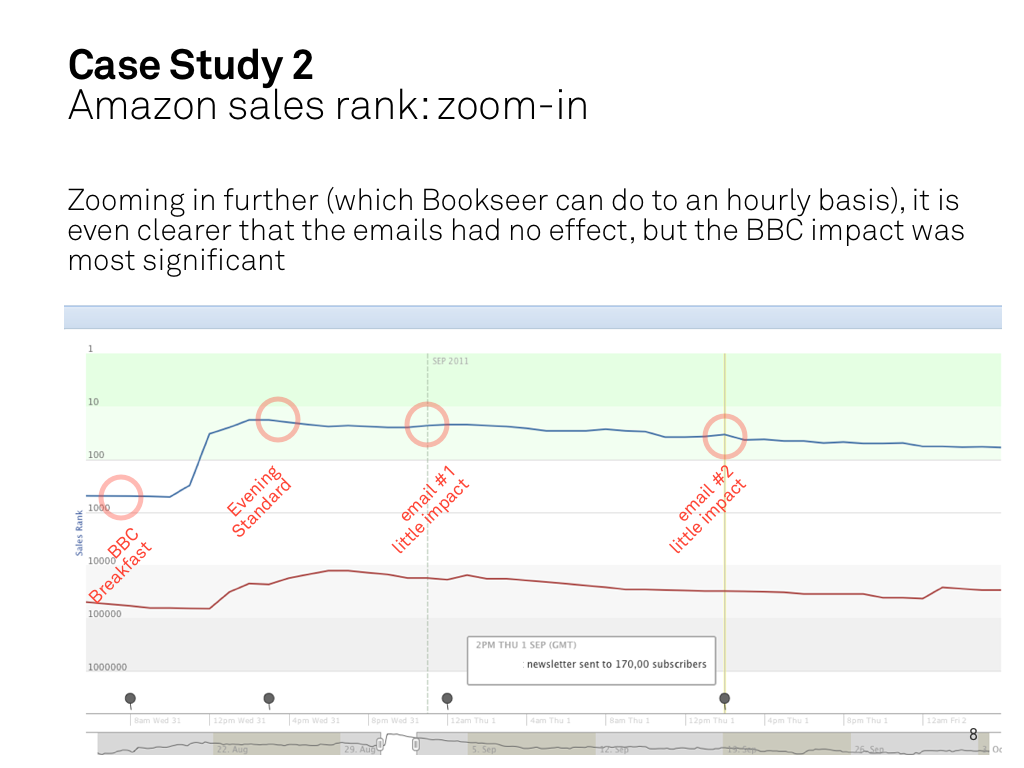

This next chart zooms in on the data on an hourly basis to show exactly when the emails were sent (1) and (2), and when the BBC and Evening Standard pieces went live. While the BBC had much more effect than the Standard, in combination they both delivered great returns—much greater than the emails.

As to effectiveness, you can make up your own minds. We have other case studies that we think overwhelmingly demonstrate the need for an entirely new approach to book marketing. The question we want people to ask is, “With this data, would I spend my money in the same way again? How would my campaign differ?”

Such an approach is one that (obviously) captures and analyzes data. More fundamentally, it is more agile in response to the data. Avinash Kaushik, analytics evangelist at Google, describes modern marketing as a “portfolio” approach planned and executed in tandem with real-time tracking and optimization. Kaushik also says that businesses should spend at least 10 percent of their marketing spend on (measured) experimentation. At Enhanced Editions, we couldn’t agree more.

Smart marketing spreads its bets wisely rather than believing that expensive media space booked months in advance is the best marketing tool. Smart marketing monitors and hones multiple activities on a daily basis to find the right mix of PR, social media advertising, search engine advertising, and direct mail. It looks at broad ranges of data in real time to see which activities work, and it tweaks and refines through split A/B testing and audience segmentation. After each campaign, it adopts its learnings into future marketing efforts, rather than repeating the same campaigns over and over again.

By being hands-on (as opposed to just throwing money at the problem) publishers can monitor and turn a failing campaign into one that sells more books and delivers a much improved return on investment (ROI).

Bookseer is designed to demonstrate the impact of any digital or print marketing approach, and to quantify it against the most tangible metrics in publishing: sales. Given the massive amount of time spent on social media, we also display Twitter and Facebook “buzz” in comparison to the other activities, so publishers can measure the ROI for this as well. Unfortunately, it’s not simple as just looking at some graphs…publishers need to change the core ways they think of marketing.

“We need to develop new skills in data analytics, listen to our readers, and understand what they want and what they will pay for.” –John Makinson, CEO Penguin

Simply measuring isn’t enough. This new marketing approach undoubtedly calls for significant training and investment in skills, skills that publishing does not currently have, yet which are fundamental to delivering the consumer-centric vision of the major houses around the world.

“[Random House must…] change from being a B2B company to being a B2C company.” –Markus Dohle, CEO Random House

In the short term, a data-centric approach allows publishers to be much more reactive to an individual campaign. They can tailor their activity to the bits that are working and stop those that aren’t. It allows them to compare the impact of PR against marketing spend and measure the outcome of a price change. They can see what worked on a competitor’s title, and they can learn from it for their own.

But, more excitingly, in the medium- to long-term, one can build up an incredibly large corpus of data that can then be mined algorithmically to run predictive scenarios for books you will publish, using data from those that have already been published.

We believe that this “big data” approach can inform future publishing strategies, answering questions like: what is the optimum price, format, and time of year to publish? Who will be the most successful retailer for a given title? Who are the top five journalists or reviewers who have the best track record of driving sales in this genre? Who are the most influential social media people to reach out to? What will the sales be, and therefore, what is the right advance to pay?

These questions have always been fundamental to bringing books to market, and it is time that real-world data played its part in answering them.

Give the author feedback & add your comments about this chapter on the web: https://book.pressbooks.com/chapter/bookseer-peter-collingridge