25

Ian Barker is the Founder of Symtext and a proud contributor to this book. You can follow him on Twitter @irbarker. Symtext’s Liquid Textbook platform is used by schools, educators, and publishers to provide educator-curated learning materials to students.

As a member of the educational technology community and as an entrepreneur, I view Clay Shirky’s 2009 blog post, “Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable”,[1] as required reading for those of us in the publishing industry. The post deals with the implosion of newspaper revenue and the utter lack of clarity on what is to become of newspapers both online and print, potential business models, even the future of journalism itself.

Shirky likens our age to that of Gutenberg, when the advent of the printing press sparked an overwhelming wave of societal change. That upheaval fundamentally undermined existing power structures and changed ways of thinking and behaving for people in the 1500s. Shirky effectively argues that—lucky us!—we are living through a time of equal transformation and uncertainty. He neatly captures the angst of an entire industry, offering scant solace:

“In Craigslist’s gradual shift from ‘interesting if minor’ to ‘essential and transformative,’ there is one possible answer to the question, ‘If the old model is broken, what will work in its place?’ The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might. (Emphasis mine.) Now is the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments, each of which will seem as minor at launch as Craigslist did, as Wikipedia did, as octavo volumes did.”

I love this: “Nothing will work, but everything might.” If ever there was a clarion call to people who want to change the game, this is it. And, much like the newspaper industry before it, book publishing across all sectors is facing tremendous pressure and uncertainty. Our much beloved Internet offers ubiquity, abundance, and immediacy. Devices and social tools have fueled an onrushing, demanding, attention-challenged digital generation that sits at the proverbial front door of educational publishers and educational institutions. We know the statistics, we see the effect on prices,[2] and we see the influence of digital book retailers.[3] It’s a new world, but few if any of us are clear about where it’s all leading.

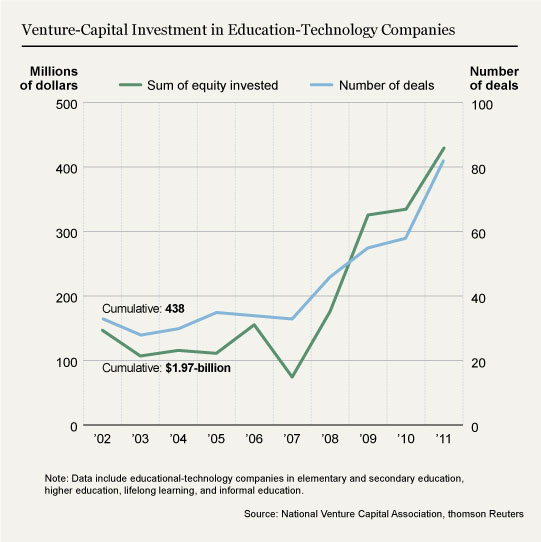

Another indicator that educational publishing is in the throes of great change: venture capitalists, who once eschewed education as stolid, resistant to change, and a slow market to develop, are suddenly alert to an immense marketplace[4] in which two of the three things we most closely associate with education—schools and books—are both changing. Investment is flooding into educational technology, much of it aimed at speeding the reinvention of learning materials and education itself.

Burgeoning demand and high levels of investment create a new reality in which the pace and probability of radical change are increasing. It’s impossible to believe that iPads, myriad competing tablets, social media platforms like Facebook, and technology developments yet to come won’t thoroughly disrupt learning materials publishing in the coming years. So, what to do?

For starters, it helps to look at this from Shirky’s point of view—nothing will work, but everything might. In a time of constrained budgets and threatened revenue, uncovering something in a large set of possibilities that might work is far from easy. But, if we don’t try, we don’t learn; if we don’t experiment, logically and scientifically, we gain no data and have no sound basis upon which to act. We can learn from observing others, but watching and doing remain latitudes apart. Now is indeed “the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments.”

“What you do is what matters, not what you think or say or plan.” From REWORK: a better, easier way to succeed in business,[5] a 37signals Manifesto

Let it not be said that we don’t follow our own advice. At Symtext, we have been experimenting for years with business model variations, target market refinements, go-to-market strategies and product development. This makes for business common sense—as a business meets the market, it learns and adjusts to make progress. We have made some pretty significant errors, but we have also learned an immense amount about what customers want in the educational marketplace.

Symtext is a collaborative social learning platform used by schools, educators, and publishers to provide “Educator Curated Learning Materials” to students. We call the platform within which these curated materials are delivered to students “Liquid Textbooks.” Materials within a Liquid Textbook may be fee-based or open, text or multi-media, educator-authored or obtained from a major publishing house. All are fully rights managed for delivery online, offline, to specific devices as well as print-on-demand platforms.

We source, assemble, and distribute what would otherwise be “unbundled” learning materials: chapters, cases, presentations, videos, and self-authored materials. Compared with complete, generic works, our custom publishing solution generates higher rates of student purchase, gives publishers new commercialization opportunities, and offers schools a means to recapture income and data generated by learning materials.

For publishers, we parse materials and attach agreed-upon pricing and permissions (e.g., defining permissible markets and related processes, such as print enabled/disabled). We support multiple price/permission conditions per object, so that, for example, publishers can commercialize materials in one market while sharing them in another.

This customization also operates at the level of the individual. The Symtext platform can deliver a specific price/permission condition to a specific student. In addition to billing and royalty management, we manage student access via the learning management system (LMS) in place at an institution. Symtext can “white label” our platform while providing publishers and institutions with detailed metrics. Because we source broadly, we have also made sure that our platform can render poor quality digital files into searchable, highlightable (i.e., useful) content. These features are all part of solving the challenge of distributing world-class content to highly demanding and digitally literate schools, faculty, and students.

Students access and use remixed materials within Liquid Textbook, device-neutral, cloud-based, HTML5 compliant readers that support social interaction. Students can consume their learning materials, “hand-picked” by their professor, on whatever device they happen to be using. Using our platform, students can add notes or highlights that may be made available in real time to fellow students in their class or section. We see this native web, integrated, multi-platform approach as vital to providing a truly interactive and social learning experience.

Although some of these features have already been made available through things like annotatable PDFs, simply delivering these fixed objects is inadequate. Students are rejecting the notion that learning materials and the learning experience are in some way islands unto themselves, separate and distinct from their other activities.

Here’s another way to look at it: Edmodo, which launched in 2007 as a sort of a Facebook for schools, reports a user base of over 6.5 million students. Their growth provides an indication that millions of students are already embracing social services. The point is less about what Edmodo does[6] (though it does directly affect publishers), but rather that students engage with educational platforms in ways that are consistent with their existing online behaviors.

Delivering PDFs isn’t consistent, regardless of how fancy the wrap is. Collectively, we have to realize that the social web, the advent of brilliantly advanced devices, abundance replacing scarcity,[7] and the rise of curation fundamentally alter the demand side of the learning materials market. Students, schools, and professors want much more than what they are getting.

This is becoming more acutely the case, as seen in the rise of asynchronous learning, blended learning, team/group collaborative learning, green consumption patterns, cost concerns (value for money), and of course our insatiable craving for understanding, via the vast amounts of data produced by online systems. None of these trends support continuation of the textbook form. They do provide proof that where we are today is nothing compared to what tomorrow holds.

Suppliers of learning materials and providers of platforms to deliver these materials must together embrace these trends and capitalize upon them. Waiting—doing nothing—only deepens the future hole from which one must escape. Now is the time for experimentation.

There are negatives to online delivery and custom digital publishing, specifically. Based upon exit surveys, some students still prefer print. When it comes to designing a custom content package, a decent proportion of educators ironically describe themselves as “lazy”: a clear impediment to wider adoption. Let’s be charitable and call those reluctant educators “focused.” We could interpret this feedback as an impenetrable attachment to the textbook form. The textbook is, after all, in some respects an almost perfect expression of the print artifact.

At Symtext, we argue the opposite. Online presentation of learning materials is improving exponentially. As usability improves, resistance to electronic content is diminishing rapidly. We can’t escape the trend:

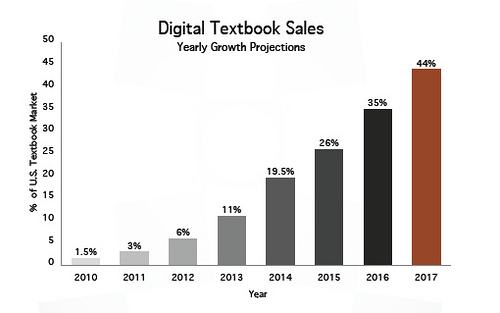

Over the next 5 years, digital textbook sales in the United States will surpass 25%[8] of combined new textbook sales for the Higher Education and Career Education markets.

We have found that professors are over-burdened with teaching, research, and administrative tasks. In response, we have partnered with publishers and schools’ on-campus staff to help with Liquid Textbook assembly and delivery. Professors do no more than provide reading lists and add annotations.

We also specifically adopted the “universality” approach: in a custom assembly model, it’s more important to be able to deliver anything an educator specifies over materials that are highly engineered. We have provided a means by which a wider universe of learning materials is available to educators, so they may in turn provide their learners with a superior educational experience at a minimum of fuss and expense. Although surveys show that students enjoy the highly engineered content available via platforms like Inkling, the vast majority of content available from educational publishers was not created in a way that can be used on such platforms, and much of it won’t be created that way in the future.

At Symtext, we work to provide a platform that:

- enables professors to deliver superior learning materials

- allows publishers to strategically target elements of their repertoire

- supports a variety of commercialization techniques

- can successfully intersect with the larger, social web

Publishers with world-class content can use the Symtext platform to reach students on an unprecedented scale and at a substantially lower cost of acquisition. Given that we are all in the business of improving education, this approach provides all participants with an enormous win.

Apart from the overall move to digital learning materials, the Symtext approach is consistent with several trends. In other contexts we are all trained that we can get just what we need—tracks from iTunes, specific podcasts, articles from newspaper sites. While we have not yet seen the same concept break out in higher education, improvements in the user experience (UX) coupled with solutions to the problems of the over-burdened professor, should propel us faster in that direction.

This does not mean that demand for readily remixable learning objects—the unbundled textbook—will eradicate the textbook. People and markets are complex; nothing happens in a straight line. We hypothesize that a decline in print textbook sales presages the end of the textbook edition cycle and the arrival of versioning, in which chapters can be rapidly (perhaps even instantly, following proper review processes) be updated for end users. We also see the rise of curated selections of recommended chapters, subject to an ongoing process of review and improvement.

There are some fairly profound consequences for the learning materials market should versioning replace the textbook edition cycle. For starters, what of textbook rentals? Without an inventory of used textbooks, renting one would seem difficult! If we think of chapters and the ebooks we can easily create from them, what of the generic textbook? What new business models will emerge?

In a world where the production of learning materials can immediately respond to demand, how is pricing affected? Perhaps we can more easily move to blended pricing, “renting” learning materials we don’t intend to keep and purchasing, in perpetuity, those we want to keep? From an admittedly biased perspective, the need for device-neutral platforms that enable seamless remixing across sources and support a social experience can only increase in size and importance.

Working with a variety of constituents in the education marketplace, we have yet to meet the professor, campus store manager, or head of IT who is interested in managing multiple publisher-specific platforms. In a similar way, we have yet to run into anyone who doesn’t think that delivering content into the classroom won’t become increasingly complex and increasingly custom in nature.

For publishers, it is increasingly impractical to be all things to all people. While there are exceptions, it is truly difficult to envision publishers becoming as skilled at developing software as they are at producing the reading materials upon which we all depend. But publishers must respond in some meaningful way.

As other chapters[9] of this book note, the production techniques publishers may adopt in response to this barrage of change are evolving quickly. At Symtext, our approach focuses more upon distribution. If we accept the premise that there are many delivery systems and business models from which to choose, but that waiting until The Answer manifests itself is just asking for trouble, then part of the answer must lie in drawing from Shirky’s advice and conducting lots of experiments. While a complete answer may yet elude us, the gauntlet has been thrown down. Here’s Shirky on publishing[10] from April, 2012:

Publishing is not evolving. Publishing is going away. Because the word “publishing” means a cadre of professionals who are taking on the incredible difficulty and complexity and expense of making something public. That’s not a job anymore. That’s a button. There’s a button that says “publish,” and when you press it, it’s done.

Words to provoke. Tools that trigger a deluge of “content” aren’t analogous to the full suite of traditional publisher activities. In some respects, it makes these core activities even more valuable (e.g., curation). But the threat level is increasing. Understanding that what is most important is doing, conducting business model and technology experiments should be done quickly, iteratively, and with minimum risk. In an unpredictable and fast-changing environment, part of what publishers need to do is manage risk through the strategic deployment of capital. Lowering risk may include transferring development costs of new technologies to partners. Let new technologies emerge on someone else’s dime.

Mitigating investment costs in new technology also means more capital left over for core publisher activities. Freed-up capital lets publishers place more markers in more places. Over time, expanding the breadth of experiments increases the probability that publishers will find the set of distribution activities that maximizes revenue. It also increases a publisher’s ability to reach readers while reducing the likelihood that it will find itself playing catch-up. That’s an experiment worth trying.

Give the author feedback & add your comments about this chapter on the web: https://book.pressbooks.com/chapter/symtext-ian-barker