Chapter 10: Intercultural and International Business Communication

Business Communication – Writing across cultures

Learning Objectives

- Describe considerations for writing to international audiences.

- Understand the differences between high context and low context culture.

Strategies for effective business communication – writing across cultures

To be certain your written cross-cultural communication meets the needs and expectations of the readers, professionals must first determine their audience and adjust their writing methods accordingly. To effectively assemble a message that is appropriate, it is crucial to understand the cultural norms of the intended audience. Implementing a series of strategies when writing to international audiences will assist in constructing an effective document.

To begin, avoid stereotypes and building generalizations. Study the target culture, or meet and interact with people from that culture. Consider clarifying acceptable topics with colleagues possessing cultural experience and knowledge. For most cultures it is advisable to buffer negative messages, and be more indirect when making requests. Don’t just assume all deliverable documents are formatted similarly. Investigate culture specific memo and letter forms. Pay attention to the date format and style preferences. Avoid using the vernacular or slang, jargon and euphemisms as they will likely be misinterpreted. Finally, consider recruiting a cultural experienced colleague to preview your document and provide suggestions or edits.

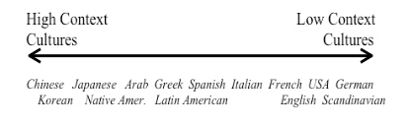

High Context vs. Low Context Communication

Ironically, language differences cause fewer problems than contextual cultural differences. With this knowledge, when writing across cultures it is imperative to reference and follow the prevailing context of that culture. In high context cultures, indirect methods of communication are vulnerable to communication breakdowns. High context cultures rely heavily on oral discourse and assume a great deal of commonality of views and knowledge. These assumptions lead to less explicit descriptions and a reliance on implicit communication delivered in indirect ways. High context cultures also place emphasis on a personal contact and establishing relationships while placing value on the collective over the individual. In low context cultures, most communication is fully and concisely composed. Written text is contractual and explicit with considerable dependence placed on the actual text. Personal relationships are less important than tending to business and the individual is valued above the collective.

According to Rutledge (2011), the implication on cross-cultural business communications is obvious. Interactions between high and low context cultures can be challenging.

- Japanese can find Westerners to be offensively blunt. Westerners can find Japanese to be secretive, devious and bafflingly unforthcoming with information.

- French can feel that Germans insult their intelligence by explaining the obvious, while Germans can feel that French managers provide no direction.

Cultural Contrast in Written Persuasive and Motivation

Another consideration in writing across cultures includes the normative layout of the communication including the opening, persuasive argument, style, closing and values projected. For example, in the United States an opening statement can request an action or grab the reader’s attention. But it Japan the opening should offer thanks or apologize. In contrast, Arab countries expect a personal greeting. When constructing a persuasive text, cultural mindfulness should dominate the message.

Consider the written persuasive contrast between the United States and Arab Countries. In the USA, persuasion offers immediate gain or loss of opportunity while in Arab Countries persuasion occurs through personal connections and potential future opportunities. Intentional and knowledgeable considerations should also be given to the style, closing and intrinsic values. Motivation is another aspect to be considered when assembling a written communication as cultures place differing ideals on the emotional appeal, recognition, material rewards, threats and values. See the tables below for more descriptions.

| USA | Japan | Arab Countries | |

| Opening | Request action or get reader’s attention | Offer thanks, apologize | Offer personal greeting |

| Way to persuade | Immediate gain or loss of opportunity | Waiting | Personal connections, future oppor. |

| Style | Short, concise sentences | Modesty, minimize own standing | Elaborate expressions; |

| Closing | Specific request | Desire to maintain harmony | Future relationship, personal greeting |

| Values | Efficiency; directness; action | Politeness; indirectness; relationship | Status; continuation |

Contrast in Motivation

| USA | Japan | Arab Countries | |

| Emotional appeal | Opportunity | Group participation | Religion; nationalism |

| Recognition based on | Individual achievement | Group achievement | Individual status; status of society |

| Material rewards | Salary; bonus; profit sharing | Annual bonus; social services; job security | Gifts for self, family; salary |

| Threats | Loss of job | Loss of group membership | Demotion; loss of “face” |

| Values | Competition; risk taking; freedom | Group harmony; belonging | Reputation; family standing; religion |

Key Takeaway

To establish and maintain a successful international business relationship, consider appropriate writing strategies to avoid preventable mistakes that may lead to costly errors.

Exercises

- Summarize effective business communication strategies for a culture of your choosing. First consider whether it’s a high or low context culture.

- Research memo and/or letter formats for a culture of your choosing.

References

Cardon, P. (2018) Business Communication: Developing Leaders for a networked world. New York, NY: McGraw Hill 2018, p.100-129.

Davis, A. S., Leas, P. A., & Dobelman, J. A. (2009). Did you get my E-mail? an exploratory look at intercultural business communication by E-mail. Multinational Business Review, 17(1), 73-98. doi:10.1108/1525383X200900004

Schaub, M. (2017) SWS Business Communication, Grand Valley State University. Powerpoint Slides: Intercultural Business Communication, Cultural Patterns and Taxonomies.