6 Focus Area 6: Store and Maintain

The activities in this section of the Toolkit will help put your organization in a position to manage your digital content over time, across generations of technology, so that the files you create or collect today can be opened and used 5, 10, or 50 years from now.

STORE AND MAINTAIN: BRONZE LEVEL

| Key Activities |

|---|

| - Establish an inventory to document existing and incoming born-digital collections. |

| - Establish an inventory to document existing and incoming reformatted analog collections. |

| - Develop a plan for storage locations of unmodified primary files and related metadata, both on-site and off-site. |

| - Develop a plan for checking and refreshing storage media on a regular schedule. |

Documenting Digital Collections

Use a collection-level log to document your existing digital collections and any new collections you create or acquire. Creating a list and updating it regularly will give you a big-picture view of the digital collections your organization is responsible for storing and maintaining. This log is not the same as the item-level inventory you may have created in the Plan and Prioritize section; instead, it’s a way to keep track of what you have digitized or acquired in digital form and where you’re storing those files. We’ve included a template for a collection level log in Appendix B.

This information will be useful for creating item-level metadata, estimating the amount of storage space needed for digital collections, budgeting, and future planning. Collection-level descriptions might also be shared with users in finding aids, as part of a catalog record, or on a website providing context for the collection.

Keep in mind that this log is a collection-level snapshot; don’t use it to describe individual items. Oftentimes, digital content doesn’t align into neatly defined collections. If that’s the case, just think in broad categories. You might determine groups based on format or topic (a map collection, a yearbooks collection, an oral history collection) or the source of the content (materials from a donor, a student intern project, photos scanned for researchers).

Types of digital collections to document in your log might include:

- Scanning projects

- Oral history interview projects

- Born-digital collections donated by a community member

- Born-digital materials created by your organization, such as event photos or newsletters

- Materials digitized for exhibits, outreach, or educational activities

- Materials digitized to fill reference requests

Basic information to record in a collection-level log includes:

- A name for the digital collection

- Total number of files in the collection

- Total size of all files in the collection

- File format(s)

- Storage location(s)

- Date of digitization

You may want to include information in your log indicating the current status of the collection, such as Digitization Done, Metadata Done, and/or Ready For Upload. This can be a helpful way of tracking which steps are completed and what needs to be done next. It is especially useful if different people are responsible for different parts of the project.

Digital Storage Plans

What Makes Storage Preservation-Level?

Digital preservation-level storage requires intentional planning, documentation, and long-term care. The primary qualities that distinguish preservation-level storage are:

Must-haves:

- Redundancy.

- Content migration plan.

- Designated storage managers.

Nice-to-haves:

- Integrity checks.

- Security / access control.

- Organization system to manage storage media and stored objects.

- Distinct geographic locations for duplicate preservation files.

Redundancy means that you have more than one complete copy of all of your digital files. Three complete copies of your data is ideal, but two copies is sufficient as you begin your storage planning. One of the biggest issues with digital storage is that it is possible to lose all your data in an action as simple as dropping a hard drive. Having multiple copies protects you from total data loss: if one copy is lost or corrupted, another complete copy exists that can be used to make additional copies. Redundancy should be factored into all digital storage planning – for instance, if you have 2 TB of files to preserve, plan for 4 TB – or, ideally, 6 TB – of storage space.

A documented content migration plan is key to the longevity of digital collections. Storage media has a finite lifespan and ages over time, while technology changes and improves. Content can’t stay in one location forever: as storage media ages, content needs to be transferred to new storage media. Plan to migrate digital collections to new storage devices every 3-5 years – or immediately if there is a problem. Anticipate storage capacity needs (including backup). Don’t wait until you run out! Research storage media types and brands before purchasing. Research and test workflows for moving content in and out of storage.

Designated storage managers are individuals who are the stewards for your digital storage. The storage manager is in charge of tasks like fixity checks, as well as knowing how storage is set up, accessed, and migrated over time. It is critical for a designated person to be in charge of digital storage: otherwise, your storage is at risk for loss due to neglect and human error.

Integrity checks are methods of confirming that your data stays the same over time. Factors like poor physical storage of hard drives or not migrating data on a schedule can lead to data corruption and loss; integrity checks are designed to identify those issues so you can address them. Integrity checks are completed by creating checksums for files, and then verifying those checksums at regular intervals (for example, once a year). More information about checksums can be found in the Gold Level of the Store and Maintain section of this Toolkit. While checksums are easy to create, they do require some technical expertise. As such, consider them a priority, but not a requirement for your storage implementation.

Security/Access control: Keep archival content separate from work space. Limit access / permissions to archival content to select individuals.

Organization system within storage: Agree on where different types of files should be placed, and label files and folders consistently (as outlined in the Describe section of this Toolkit).

| Bronze Level: Resources and Tools |

|---|

| “Digital Preservation Webinar Series: Identify.” Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Illinois (CARLI), 2014. |

| Nelson, Tom. “Do HDDs Or SSDs Need ‘exercise’? The Rocket Yard Investigates.” Rocket Yard, 2018. |

| “Backblaze Hard Drive Data and Stats.” Backblaze, 2023. |

STORE AND MAINTAIN: SILVER LEVEL

| Key Activities |

|---|

| - Move copies of files to their on-site and off-site storage locations. |

| - Implement a plan for checking and refreshing storage media on a regular schedule. |

| - Develop a plan for checking file integrity (fixity). |

Digital Storage is Not a Backup

The type of storage we’re talking about here is NOT the same as a backup system. A backup is a snapshot of your computer at a certain moment in time[1]. Backups enable quick restoration after accidental data loss, system crashes or other errors. Backups are typically saved for 30-90 days. Digital archival storage provides an environment where the content you aim to retain over many years — your primary files and related metadata — can be kept safe and unchanged. Digital storage requires continued management to ensure that hardware remains operational and that digital files do not succumb to bit rot, misplacement, or erasure.

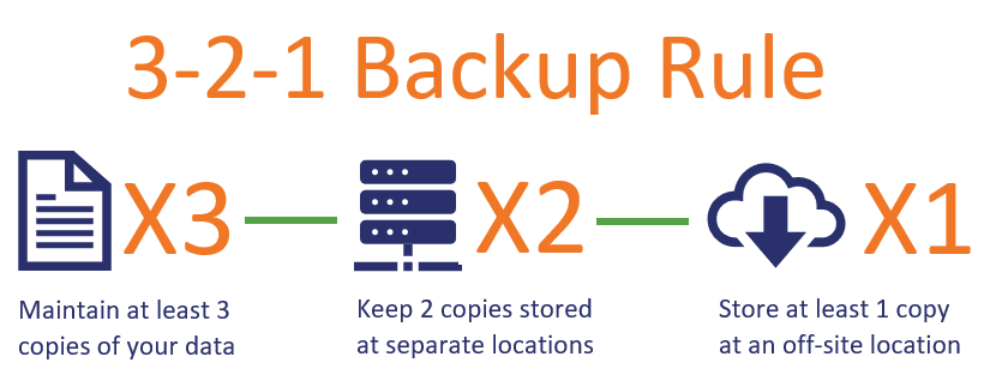

The 3-2-1 Rule

The 3-2-1 Rule is mentioned frequently in relation to digital storage[2]. It means:

- 3 – Make three copies of your digital files. That way you always have a copy you can recover if one storage location fails. This is the LOCKSS principle: Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe.

- 2 – Use two different storage media. Don’t rely on one form of technology. Make at least one of your copies in another storage format.

- 1 – Store one copy in an offsite location. In case of disaster, like a flood or tornado, keep one copy of your files in a different geographic location, such as with a partner in another county or state, or with a cloud storage provider.

Selecting Storage Solutions

Regardless of which storage solutions you choose, consider them “cold storage” for your unmodified primary files and their related metadata. To avoid accidentally deleting, moving, or modifying those primary files (aka archival files or preservation files), keep them stored separately from any access copies. Refer to the Digitize section of this Toolkit for more on the difference between primary files and access copies.

Network Attached Storage (local server) is a strong storage option if that is available to you, either on-site in your own building, or with a local partner such as your city or county government. To avoid the chance of files getting accidentally moved or deleted, limit the number of people who have access to your storage on the network drive – don’t use a shared or public drive (often labeled as C:, D:, or S:).

Other storage solutions include the many flavors of cloud storage (see below) and external hard drives. The Digital Preservation Outreach and Education Network (DPOE-N) recommends hard disk drives that support RAID, which stands for Redundant Array of Independent Disks. In a RAID system, if one hard drive fails, the second one will keep the data intact[3]. Be aware that external hard drives have short lifespans! Every three to five years, you’ll need to copy your files to a new external hard drive and retire the old one. (This is what “refreshing” your storage media means.)

Removable optical media, specifically gold “archival” DVDs or M-discs, may be an appropriate choice for small organizations with limited budgets, as long as these are not the only type of storage you use. Do not use USB flash drives, CDs, or rewritable DVDs for long-term storage. Flash drives (aka thumb drives or memory sticks) can easily be overwritten or damaged, and their small size makes them easy to misplace. Optical drives to read CDs and DVDs are no longer standard in computers; neither are earlier generations of USB ports[4]. If you have files on these types of media that you want to keep, copy those files to a more stable storage location as soon as you can.

Caring for Storage Media

External and internal hard drives require care similar to other audiovisual carriers. The basic components of storage media care include:

- Store in a cool, dry environment.

- Exercise / activate drives at least every 4-6 months.

- Plan to refresh storage every 3-5 years.

- Diversify storage media.

Store in cool, dry, environment: This gold standard applies not only to film and magnetic audiovisual media, but all digital storage media as well. When hard drives are stored in a cool, dry environment, they are able to operate at their optimal ability with minimal media degradation. This provides a stable environment for your data. Extremely high or extremely low temperatures (below 40F or above 120F), fluctuating temperatures, and high humidity can negatively impact these devices.

Exercise / activate drives: When drives are powered on regularly, at a minimum of every 4-6 months, it helps to reduce the risk of magnetic field corruption and ensure that the drive’s hardware (platters and spindles) are operating properly. (Note: When you’re exercising a drive, that’s also a great time to perform fixity checks on files.)

Plan to refresh storage every 3-5 years: Even with proper care, hard drives have documented increased failure rates as they age. Purchasing hard drives every 3-5 years ensures that your storage media are running properly and compatible with new technology. When purchasing new drives, consider the digital environment in which they will operate. Is your workstation a Mac or a PC? What operating system are you running? What kinds of connectors does your workstation support? Take note of reviews related to issues such as consistent drive failures and difficulty extracting content due to proprietary software.

Diversify storage media: When upgrading your storage system 3-5 years from now, it’s worth considering buying different brands of hard drives. This is done in the interest of avoiding data loss due to common media issues. If you store identical copies of your data on the same types of hard drives, there is a slim possibility that an issue common to that type of hard drive will lead to data loss. If you store identical copies of your data on different media (G-Tech and Seagate brands, for example), an issue with one model may not affect the other.

How much storage space do I need?

When making decisions about where to store your digital content, it helps to know how much content you need to store. As you’re doing that math, keep in mind the 3-2-1 Rule and be sure to plan for enough storage space for all three of your copies.

A quick formula for getting a rough estimate of how much storage space you need for scanned photographs or other images is:

Total number of files x Average file size, in MB x 3 copies = _______ MB

Then add on another 10% to that number, to account for access copies, metadata, and any other supplementary files you’ll need to store. Estimating storage for audio and video files is a little trickier. Not only are they huge, but the file size can vary significantly depending on the total length of the recording and other factors.

Off-Site Storage

Off-site storage refers to a data storage facility that is physically located away from your organization. Using off-site storage can mean placing a hard drive with a community partner across town; it can mean a copy is stored on the county server a few hours away; it can mean cloud storage in a secure location across the country. Your needs and available resources will dictate which option is best for your organization, but the idea is that, in the unlikely event that a flood, tornado, or other disaster hits one storage location, you’ll know that you have another copy stored safely far away.

Cloud storage is a widely-available option for off-site storage. Storing data “in the cloud” really just means putting it on someone else’s servers. You upload your digital objects to a third-party storage provider, and they maintain their own data storage facilities and conduct their own backups of the data. Cloud storage options such as Google Drive, iCloud, OneDrive, Dropbox, Backblaze and Carbonite generally have limited storage space available in a free tier, with the option to purchase additional space.

| Silver Level: Resources and Tools |

|---|

| Norton-Wisla, Lotus. "Getting Started with Digital Preservation in a Small Institution Webinar." Sustainable Heritage Network, 2021. |

| How long will digital storage media last? Library of Congress, n.d. |

| Reliable Storage Media for Electronic Records. Illinois Secretary of State, 2023. |

| Van Malssen, Kara. Cloud Storage Vendor Profiles. AVP, 2017. |

STORE AND MAINTAIN: GOLD LEVEL

| Key Activities |

|---|

| - Document your storage decisions. Where is it? Who can access it? How? |

| - Implement plan for checking file integrity (fixity). |

| - Document procedures used for any file checking tools and perform checks on a regular schedule. |

Storage Management

Your work’s not done after you’ve moved your files into storage — they need active management. Use a Storage Log like the example below to document where files are stored, when they were moved to storage, how often you will check the storage (audit schedule), and how often you will need to update the storage (hardware replacement schedule), if applicable.

Storage information to document for ongoing management:

- Network Attached Storage/local server: Find out what the backup protocols are for your server. If it is networked, someone is managing it and likely has a schedule of backups they follow. How often? To what media?

- Cloud storage: Who in your organization has access? Where are the username, password, or other needed authentication stored? What is the viability of this service provider over the next 1-3 years?

- External hard drives or other removable media: When was it purchased? What brand? Where is the physical drive stored? When will it need to be replaced? (external hard drives should be replaced every 3-5 years).

Sample storage log

| Storage format and location | Date implemented | Audit schedule | Hardware replacement schedule | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location 1 | 1 TB Western Digital hard drive, in director’s office | January 2020 | Every six months (Jan. and July each year) | Every three years. Next replacement date: January 2023 |

| Location 2 | Carbonite Safe, installed on curator’s desktop computer | January 2020 | Every six months (Jan. and July each year) | N/A |

| Location 3 | Dedicated folder on the server managed by public library. | June 2020 | Annually | Refer to partnership agreement with library. |

Checking File Integrity (Fixity)

The term fixity is used to describe the stability of a digital object. The goal of digital archival storage is that your files remain unchanged over time. The challenge is that digital files can degrade or change, and those changes are often invisible to the human eye. Whenever a digital collection is moved, processed, or altered, things can go wrong. Your network connection drops out while you’re moving files, a disk gets full and subsequent data copied there is lost, a software bug or crash leads to unexpected results, or human error leads to unintentional deletions or changes.

A simple way to catch some of these kinds of potential errors is to keep an eye on your total file counts and sizes. For example, if you’re copying a folder from an external hard drive to a cloud storage location, check the total number of files and total folder size before and after the move to make sure nothing got dropped along the way.

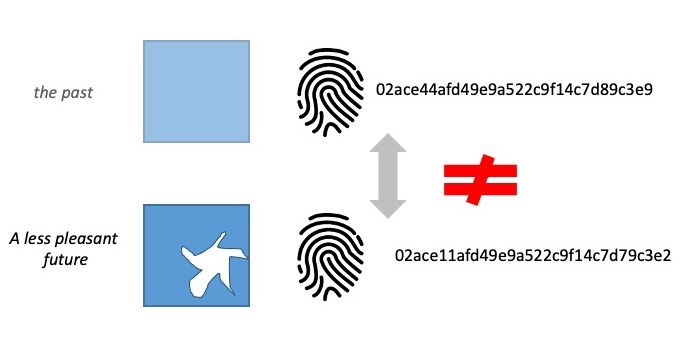

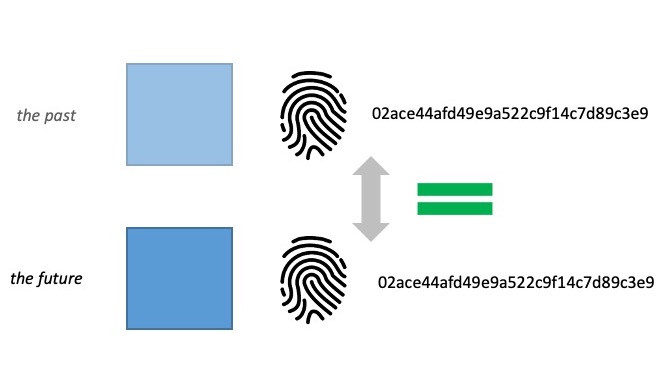

The most reliable way to tell if your digital files have changed is by using software tools to generate and monitor checksums. A checksum is a mathematical algorithm run on a file and its resulting value. You can think of this as a digital fingerprint. If a file has remained authentic and stable, with no changes, its fingerprint (checksum) will also stay the same. If a file becomes corrupted, degraded, or is otherwise changed in some way, its fingerprint (checksum) will change.

There are software tools available to perform these fixity checks. A checksum-monitoring utility may be built into your collections management system. Or you can use a free or low-cost checksum utility such as Fixity Pro, MD5 Summer, or FastSum.

Checksums do not prevent file corruption or degradation from happening, but they let you know there’s a problem so you can address it. If a file is discovered to be altered, you can replace it with an unaltered copy from one of your other storage locations. If lots of files have changed, that’s a symptom of a bigger problem – you may need to update your storage media or revisit your file transfer procedures.

When to check file fixity (by comparing file counts, total file size, and/or checksums):

- When files are first created or acquired

- Before files are moved to a new location

- After files are moved to a new location

- On a regular schedule, i.e. every three, six, or twelve months

| Gold Level: Resources and Tools |

|---|

| “How-To Guide: Fixity.” Outagamie Waupaca Library System, 2018. |

| What is Fixity, and When Should I be Checking It? National Digital Stewardship Alliance, 2014. |

| Boyd, Doug. “The Checksum and the Preservation of Digital Oral History.” . 2012. |

- “Digital Preservation,” University of California San Diego Library. https://library.ucsd.edu/lpw-staging/research-and-collections/data-curation/digital-preservation/index.html ↵

- Adapted from Steve Whitmer, “Digital Archiving,” University of Michigan Library. https://guides.lib.umich.edu/c.php?g=992751&p=7183005 ↵

- “Emergency Hardware Support,” Digital Preservation Outreach and Education Network. https://www.dpoe.network/emergency-hardware-support/ ↵

- Steve Whitmer, “Digital Archiving,” University of Michigan Library. https://guides.lib.umich.edu/c.php?g=992751&p=7183005 ↵

- Illustration of unchanged and changed checksums. Adapted from POWRR Professional Development Institutes for Digital Preservation slides developed in partnership with the Digital Preservation Coalition. “Bit preservation - getting started.” https://powrr-wiki.lib.niu.edu/index.php/File:Bit_preservation_-_getting_started_v05.pptx ↵

The term digital preservation encompasses all of the activities, policies, strategies, and actions required to ensure that the digital content designated for long-term preservation in maintained in usable formats, for as long as access to that content is needed or desired, and can be made available in meaningful ways to current and future users, for as long as necessary regardless of the challenges of media failure and technological change. Digital preservation goals include ensuring enduring usability, authenticity, discoverability, and accessibility of content over the very long term.

Redundancy refers to the creation and retention of multiple near-identical copies of the same data, stored in different digital locations.

A checksum is a unique numerical signature derived from a file. checksums are used in fixity checking in order to compare copies.

Digital storage refers to a digital method of keeping data, electronic documents, images, etc. in a digital storage location, usually a hard drive or in cloud-based storage. Archival digital storage is not the same as a backup ー archival storage keeps content accessible for future users and computers, while backups keep your computer files working safely and securely.

The 3-2-1 rule informs digital preservation and storage strategies. Maintain three copies of your digital files on two different storage media with at least one copy stored off site.

Digital preservation principle that Lots Of Copies Keep Stuff Safe.

Disaster risk zones show the likelihood of various natural disasters affecting a particular geographic area. It is advisable to have digital storage options in various disaster risk zones different from your own; for instance, if your area is prone to earthquakes, choose cloud-based backups in an area not prone to earthquakes (and ideally not prone to natural disasters at all).

A dark archive is a repository that stores archival resources for future use but is accessible only to its custodian. A dark archive does not grant public access and only preserves the information it contains. The information can be released for viewing depending on its donor and organizational restrictions, at which time it is no longer considered "dark."

Cloud storage is a way to save data securely online so that it can be accessed anytime from any location and easily shared with those who are granted permission. Cloud storage also offers a way to back up data to facilitate recovery off-site. Cloud storage services include Google Drive, Dropbox, Box, etc.

Hard disk drives are a form of magnetic media that have magnetic platters read by spinning arms.

Fixity refers to the “unchangedness” of data, usually evidenced by identical and persistent checksums generated from the same file over time. Fixity refers to the stability of a digital object over time.