12

Authors: Brian Majszak and Troy Richard

Author Biographies:

Good day to you my fellow Social Workers! My name is Brian Majszak, and I co-authored this chapter. Specifically, I wrote the Introduction and Disclaimer, as well as sections II, IV, and VI.

We authors felt it appropriate to detail why we chose to write our particular chapter. For me, working with Veterans is my dream. It has been ever since I got out of the military.

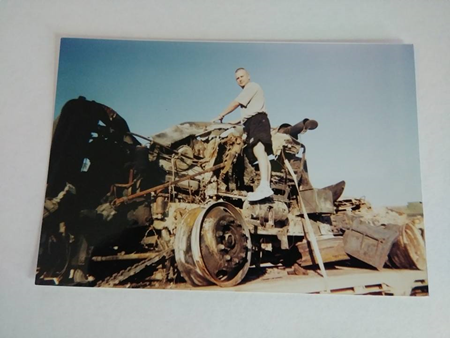

The picture above is of myself (left) along with my supervisor and closest Army friend, Sergeant Moore. During the latter parts of High School, I decided to enlist. I served eight years in the Army: four years in Active Duty (over a year of that in Iraq), two years in the Army National Guard, and two years in the Army Reserves. I’d always joked that it would be just my luck that World War III would break out as soon as I joined. Unfortunately for us all, I wasn’t too far off. I was in Basic Combat Training on 9/11. I recall our Drill Sergeants telling us cryptically that 90% of us were going to war (without telling us specifically what happened that day, or detailing the specifics of the attack). I completed all my training and was stationed in Fort Polk, LA. I wasn’t there for very long though. Just a couple of years later and my Drill Sergeants’ prophecy came true: I, along with the rest of the 1st Squadron, 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, were patrolling the streets of Baghdad, Iraq by April 2004. All in all, after we cleaned up the damage the invasion had wrought, trained up police and Iraqi Civil Defense Corps, and squashed an uprising or two, we were home after a short 16 months.

After that experience, I was done with the military. The war in Iraq was so politically divisive that I had no desire to continue being a part of it. I decided to get out, but the allure of the military has a far-reaching grasp. I miss it. I will always miss it. I decided that I still wanted to help former service members out if I could. I went back to school and discovered social work. During that time, I learned that the emotional rollercoaster of my life since getting back from Iraq was attributed to my struggles with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, which only solidified my desire to work with Veterans. The rest is history.

I am very passionate about providing service and assistance to my fellow brothers- and sisters-in-arms. In fact, when I first began social work, I did not want to work with any other population. Shortly after completing my BSW, I was very fortunate at landing a job at the local Community Action Agency and was the Lead Case Manager and Supervisor of the Supportive Services for Veteran Families grant for around three years. I’d also worked at the Veterans Office at Northwestern Michigan College setting up VA education benefits. Overall, I have around six years of experience as a professional working with veterans. Who better to assist them on the long road of life than one who is familiar with their daily struggles?

My name is Troy Richard. I am one of the co-authors of this chapter titled Service members and Social Work. I wrote sections I, III, and V. I am going to give you a glimpse into my history and what qualifies me to take on such a task. I am a veteran with 23 years of service, which 11.5 of those years I spent on active duty. My career has been a wild ride, but it has also been fulfilling and has made me into the man I am today. I first joined the United States Navy in 1988, straight out of high school. I was a part of the USS Vincennes CG-49. This is a Ticonderoga-class Guided Missile Cruiser outfitted with the Aegis combat system that was in service with the United States Navy from July 1985 to June 2005.

I began my time as a Deck Seaman. After a significant process that involved studying and testing, I elevated my rating to SK, or Storekeeper. I made E4 (Specialist) before I switched branches to the Army. I participated in the ritual for crossing the equator called pollywog or shellback.

In 1991, I left the Navy and joined the Army National Guard. I served with the 125th Infantry unit which is a regiment under the U.S. Army Regimental System out of Saginaw, Michigan. The regiment currently consists of the 1st Battalion, 125th Infantry, and Infantry in the 37th Infantry Brigade Combat Team. I spent 2.5 years training at Fort Custer Training Center in Battle Creek, Michigan. During that time, I was transitioning from enlisted to officer, however, I resigned my commission and remained an enlisted member as an E-6 (SSgt). In 2002, I joined the Army Reserves as an instructor with the 100th Training Division for 88M (Transportation). This was an exciting time in my life because I got to give back to many soldiers regarding combat, tactical driving, and leadership.

My combat dates are as follows:

1990-1992 In support of both Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm.

1993-1994 I participated in the “War on Drugs,”

2003-2005 OIF (Operation Iraqi Freedom).

After 2007, I joined the 127th Air National Guard. I remained in the Air Guard until I retired as an E7 (Sergeant First Class). I am a father of five boys and currently reside in Bay City, MI. I have been diagnosed with aspects of the mental health struggles detailed throughout the chapter. I hope and pray that this chapter does justice for all member who have served in our military. To my fellow veterans and former Service Members, and to those seeking to make a positive difference, I salute you! Thank you for reading and I hope it was eye opening and educational.

Introduction

You will likely find veterans in just about every facet of the social work profession. For example, veterans are young and old, and come from very diverse backgrounds. Veterans have families, spouses, and children. They struggle with poverty and experience homelessness. They seek aid from state and federal assistance programs, and struggle with mental and physical health disorders, both military-related and non. Veterans pursue employment, and often struggle to bridge the gap between military and civilian life, battle addictions, and are part of the criminal justice system. Though military core values stress excellence and a “never lose” mentality, veterans are no strangers to defeat. Regardless of whether you set out to work with veterans or not, it is very likely that you will interface with them at some point or another. Throughout this chapter, general background information on cultural aspects of veterans, as well as common benefits and services available to former members of the armed forces will be discussed. Specific to this section of the chapter, the question of “what is a veteran?” will be reviewed, and will include some key characteristics of military life, rank, and pay. Some insight on basic military organization and structure, core values and some common misconceptions, will also be addressed, along with the differences between Active Duty and Part-time components. Additionally, common military language and how it might impact services will also be provided. Hopefully better prepare you for the day a veteran knocks on your office door seeking aid.

With all that in mind, it’s important to stress that when talking about any cultural information, it is impossible to avoid generalizations. We, the authors, as veterans ourselves, feel safe talking for some, but not for all. This is basic information, after all. We have a chapter to define what could easily take volumes to adequately articulate. With that in mind, the views and opinions shared from this point forward are that of our own, and were peer-reviewed by members of academia and by those currently working in and/or are a part of the veteran community.

Section I. Components of the Military

Army

The United States Army serves as the land-based branch of the U.S. Armed Forces. The U.S. Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) defines the Army in Section 3062 of Title 10, U.S. Code of Military Justice. It’s mission is to preserve the peace and security, provide a defense for the United States and the Commonwealths and possessions and any areas occupied by the United States. It supports the national policies implementing the national objectives overcoming any nations responsible for aggressive acts that imperil the peace and security of the United States.

Navy

The mission of the United States Navy is to protect and defend the right of the United States and our allies to move freely on the oceans and to protect our country against her enemies. UCMJ defines the Navy in Section 3062 of Title 10, U.S. Code of Military Justice.

Marines

The United States Marine Corps (USMC) is a branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for providing power projection, using the mobility of the US Navy to deliver rapidly, combined-arms task forces on land, at sea, and in the air.

Air Force

According to the National Security Act of 1947 (61 Stat. 502), which created the USAF: §8062 of Title 10 US Code defines the purpose of the USAF to preserve the peace and security, and provide for the defense, of the United States, the Territories, Commonwealths, and possessions, and any areas occupied by the United States. The stated mission of the USAF today is to “fly, fight, and win in air, space, and cyberspace.”

U.S. Coast Guard

The Coast Guard is one of our nation’s five military services. It’s core values—honor, respect, and devotion to duty – are the guiding principles used to defend and preserve the United States of America. The Coast Guard protects the personal safety and security of our people; the marine transportation system and infrastructure; our natural and economic resources; and the territorial integrity of our nation–from both internal and external threats, natural and man-made. We protect these interests in U.S. ports, inland waterways, along the coasts, and on international waters.

Each branch of service has their own traditions, trademarks, flags, uniforms, requirements, boot camp, and way of training; however, combined they stand together for the protection of freedom, equality, and rights govern to us by us. The men and women who serve the United States are regular people but when they join the military service a higher standard of personal conduct, integrity, respect, honor, and sacrifice is expected.

Section II. Military Culture

Military culture is comprised of the environment veterans have been a part of, and has had a major impact on the lives lead since exiting the military. It is important for those that have never served in the military to be familiar with some fundamentals of military service. Before moving on to specific information, there are a few key terms and characteristics that help describe some common threads that make up the backbone of military culture. These components include Camaraderie, Pride and Esprit de Corps, Tradition, and The Mission.

Camaraderie

The first term, camaraderie, is arguably the largest component of military culture. The relationship dynamics that arise out of a group of individuals whose success or failures dictates the groups’ fate is a hint of the camaraderie experienced in the military. The companionship that comes out of that type of environment is lifelong.

To further reinforce this point, refer to the following quote from an article from the newspaper that focuses and reports on matters concerning the armed forces, Stars and Stripes:

“It’s an unbreakable trust and kinship forged as men push their brains and bodies to the limits each day, together, in an environment that won’t forgive them should one man mess up. One guy keeps the next guy going, to keep all the brothers from falling.”

(Ziezulewicz, 2009)

This TED talk by Sebastian Junger entitled Why Veterans Miss War might help describe the strong sense of camaraderie a little better. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGZMSmcuiXM

Pride and Esprit de Corps

Pride is undoubtedly a term you are familiar with. To a member of the military, pride (which could also be called Military Bearing) is a driving force behind much of our actions. The uniforms and the way they are worn, the walk, the talk: it is very explicit, strenuously orchestrated, and delivered with the highest possible standards of excellence. It’s meant to present an imposing force that inspires faith in our allies, and fear in our enemies. It stirs competition between service members, especially with those in different branches of the military (Sion, 2016). It boosts confidence to the point of thinking and feeling invincible. Pride is understandably a huge driving force in the actions of all those who don the uniform (Schumm, 2003, p.837). All of this is magnified by what the military refers to as esprit de corps.

Esprit de corps is essentially the glue that keeps a group of military men and women united; the common spirit that invokes enthusiasm, devotion, and pride in the unit a service member is part of. With hope and aspirations of being the best, they strive to bring honor to those serving with them and to those that served before them in the same unit. A phenomenal example of this can be found in the following video, Marine Corps Silent Drill Platoon Stun a Packed Arena. On the surface, this is a spectacle aimed to entertain. Under the surface, the preparation, precision, and delivery are all aspects of pride. Pride in themselves, pride in their brothers and sisters they serve with, pride in their unit (esprit de corps), and meant to invoke pride in the country’s military. The next component, tradition, has its roots in pride and esprit de corps.

Tradition

Any group of Soldiers, Marines, Airmen, or Seamen are organized into various-sized groups commonly referred to as units. (More on military organization will be detailed further in this chapter.) Each unit has its own traditions and each military member is part of those traditions, carrying on a tradition of honor, pride, ability, courage, and competence. The things service members do while assigned to that unit echo throughout time and bring honor or shame to those the individual is serving with, and those that served before him or her. In the HBO series Band of Brothers, the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division was glorified for their valor, courage, and bravery during various operations of World War II. Such a fine example can be tarnished and that reputation dwarfed by just a few poor decisions of an overzealous service member.

The Mission

The last term is potentially the most important one, and potentially the most ambiguous. The mission is any task that a service member or group is focused on at any given moment. And that task becomes the embodiment of their being until the task is completed. That task can be small or large and may require individual effort or a group approach. Furthermore, each specific unit within the military carries on its own specific mission, regardless of the size of the unit. Within the military, the Mission, especially when in combat, always comes first. It is placed in higher priority than hopes, dreams, health, and safety.

What is a Veteran?

So now that you have a basic understanding of what it is like to serve in the United States military, the next topic to be addressed is the term Veteran. What is a Veteran? This may seem a simple question at first, but in actuality it is a very murky subject. This is evident by conducting a quick online search for “what is a veteran.” Search results yield a new definition for practically every different site you go to. Quite frequently, the various sites contradict one another, as well. While most declare that anybody who has served in the military is a veteran, regardless of any other details, some sources include more specific categories, such as total time served in the military, if they served at times of conflict or war, or type of discharge character. To make matters worse, there is confusion among former service members as to what a veteran is, as well.

The safest answer can be gathered from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). The following exert helps to clear some of the fog: “Title 38 of the Code of Federal Regulations defines a veteran as a person who served in the active military, naval, or air service and who was discharged or released under conditions other than dishonorable (Veterans Authority, 2017).”

The different branches of the military, differences between Active Duty and the part-time components, as well as the different discharge characters will be detailed later in this chapter. For now, the above definition suggests that if they served at all in any branch of the military and were not dishonorably discharged, they are classified as a veteran. This same definition will be utilized for the purposes of this chapter. However, the initial question of what is a veteran is not entirely answered yet.

As a social worker, rarely will you yourself have to award veteran status to any individual. If and when you do, the program you are working with will have its own detailed and specific criteria to establish veteran status. For example, when this author (Brian) administered the Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) grant, a veterans-exclusive, VA-funded grant with aims of ending homelessness among veterans, the criteria stated that a veteran was an individual who had served at least one day on active duty outside of initial training, and also received any discharge character other than dishonorable (Department of Veterans, 2016).

Other veteran benefits awarded through the VA have their own eligibility criteria. This means a veteran may be eligible for some benefits, such as healthcare, and be ineligible for others, such as education benefits or small business loans. This may help in explaining why some veterans are not fans of the VA. Likely due to a lack of consistent definition, there are many former service members who do not view themselves as veterans. Some may even get defensive or react with guilt or shame when asked, “are you a veteran?” The most important take away from this portion of the text is that the term veteran is foggy at best. If you need to know if an individual was formerly affiliated with the military for whatever reason, you may find the best approach is to simply ask if they ever served in the military. This removes “veteran” from the equation entirely, and may assist in developing rapport with the individual as well (Conard, Allen, & Armstrong, 2015).

Rank Structure and Pay

All individuals affiliated with the military are given a rank in some form or another. Even civilian contractors that are affiliated with the military often have a rank structure that, according to some, has corresponding weight and gravitas as military rankings. Each different military branch has its own unique rank structure. Very specific information regarding the various rank structures can be found at Military.com via the following link: http://www.military.com/join-armed-forces/military-ranks-insignias.html)

To provide a very basic overview, each branch of the military has essentially two separate rank structures: enlisted and officers.

Enlisted: Enlisted service members are those who were recruited into the military via a recruiter and do not have a military commission. This category can be additionally separated into three categories: lower-enlisted, non-commissioned officers, and Senior non-commissioned officers.

Beginning with the lower-enlisted, these men and women are typically either new to the military, or as a result of disciplinary action have been demoted. In all branches of the military, ranks E-1 through E-4 would fit into this category. They are typically new, have little responsibility outside of taking care of themselves and their assigned equipment, and have the lowest level of pay.

Non-commissioned Officers (ranks E-5 through E-6), also referred to as NCOs, are enlisted personnel that have been awarded their rank through a designated promotion board, have a wide range of knowledge regarding their assigned specialty and of various military regulations and doctrine, and can also be found leading small- to medium-sized groups of service members.

Senior NCOs includes ranks E-7 through E-9, have an abundance of experience and training, having served in their respective branches for at least 15 years or more, are the highest trained enlisted service members. They typically have mastery over multiple specialties and can be found leading medium- to large-sized groups (Military.com, n.d.a).

Officers: Officers are traditionally the leaders within the military and are responsible for strategy. An officer might command what to do, and it typically falls to a lower-ranked officer or (more likely) an NCO to figure out how to do it. There are significantly fewer officers in the military than enlisted personnel, and all officers are higher ranked than any enlisted service member. In other words, an O1 brand new to the military technically outranks an E9 with 35 years of experience. A subsection of officers exists which are Warrant Officers. Warrant Officers do not have quite as much authority as standard officers, per se; however, Warrant Officers are often experts of their given specialty, and their knowledge and experience affords them just as much (though usually more) respect as their officer kin (Military.com, n.d.a).

As for pay, a chart of all paygrades, which are equivalent to the individual’s rank, can be found at the below link. It must be noted that this is a basic pay scale, and does not include information regarding the various additional funds an individual can receive, such as Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH), Basic Allowance for Sustenance (BAS), Hazardous Fire Pay, and Family Separation Pay. http://militarybenefits.info/2017-military-pay-charts/

General Organization

If you’ve ever heard such phrases as Platoon, Company, Battalion, Squadron, Wing, or Regiment, these are words that describe the size of the unit, which command the unit belongs to, and a general description of its capabilities and potential purpose. A ton of information is available about all the specific words, acronyms, and annotations, but the specifics are not necessarily important here. Suffice it to say, the military is organized in an incredibly intricate manner, and has accompanying policy that dictates precisely how much personnel and equipment it needs to accomplish its unique mission. Very basic information pertaining to military structure can be found here (Vetfriends.org, n.d.).

As a social worker, the takeaway from this section is this: the unit each individual veteran has served in is often at the core of the pride he or she has for his or her time in the military. These units are incredibly important to veterans. It may be greatly beneficial for you to look into some background history of your client’s unit, as nearly every unit within the military has its own website detailing its history and traditions. This could be a very quick and easy way to gain a lot of rapport with your client.

Active Duty and Part-Time Components

Each branch of the military is comprised of those on Active Duty, and those as part of either the Reserve or National Guard components. The differences between them are fairly obvious: Active duty is serving in the military full-time, while National Guard or Reservists typically serve in the military one weekend each month, with an additional two-week training event each year. It is important to note that while Active Duty and Reserve members are federally funded and monitored, National Guard members are state-funded and report to the Governor of whichever state they originate from. National Guard units are the modern equivalent of state militias (National Center for PTSD, 2012).

Beyond how often the various components don the uniform and serve, or who signs their paychecks, there is a very explicit difference in the benefits and prestige of each component as well. Refer back to the section where what a veteran is was discussed. As far as the majority of federal VA benefits are concerned, National Guard members or Reservists are not viewed as veterans unless they have served on Active Duty in support of either a local or state emergency or combat operation. For example, National Guard members and Reservists deployed to assist the areas struck by Hurricane Katrina were likely placed on Active Duty (effectively making them Active Duty members, albeit temporarily) and henceforth qualified for a variety of benefits they were otherwise ineligible for. Meanwhile, those that honorably completed their weekend duties and two-week training exercises per year with no other periods of service likely found themselves with little to show for it after their military contracts expire, aside from the memories and experiences, and a pension if they served long enough (Veterans Authority, 2017).

Core Values

Much as Social Workers follow the NASW Code of Ethics, each branch of the military has its own unique set of values that all members adhere to. Those values are as follows:

Army – Loyalty, Duty, Respect, Selfless Service, Honor, Integrity, Personal Courage

Navy, Marine Corps – Honor, Courage, Commitment

Air Force – Integrity first, Service before self, and excellence in all we do

Whilst serving in the military, the above core values become each individual’s creed while they serve, and each veteran likely still follows those values well after their terms of service ends. As some of you may have noticed, the one common value in all of them is honor. With that in mind, as you work with veterans in the future, if you establish yourself as an honorable person you will likely earn the respect and trust of your client. Adversely, if you do not display honorable qualities, you will lose that respect and trust and will likely not get it back. Consistency and honesty is the key. In our experience, veterans are typically apprehensive to work with civilians, and some may be actively looking for a reason not to trust you. Make it hard for them to not trust you. Earn respect, and you will likely be awarded with an intense loyalty (Department of Defense of Core Values, 2009).

Communication

Within the military, clear, concise communication is a requirement. Lives depend on it. The military often utilizes a phonetic alphabet to aid in this. This means that while civilians would say A, B, C, a veteran would likely say Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, etc. It isn’t necessarily to learn the phonetic alphabet (though it couldn’t hurt and might create some common ground with you and your client), but being clear on your communication is paramount. Veterans are trained to pay close attention to the words others say, and will likely let you know that your message was received and understood (Roger, Lima Charlie/Loud and Clear, Wilco/Will Comply, ring any bells?). Veterans will cling to the words you use, and will likely follow them like it’s their mission. Help them out and be very clear.

For example: I will see you next Thursday, June 15th, at 2:15 pm in my office. Bring documents 1, 2, and 3. You’ll need a pen and a pad of paper to write on. Not See you Thursday around 2 with the stuff we talked about. Talking in ambiguities will likely cause anxiety for a veteran, and could potentially impact your relationship. Furthermore, for those of you soft-spoken social workers out there: those veterans with hearing disturbances notwithstanding, speaking softly or quietly to the point you can barely be heard or understood is likely to frustrate the veteran, not to mention cause undue stress at not fully receiving or understanding your message.

Common Misconceptions

Before this section comes to a close a few common misconceptions exist, and might cloud perspective on veterans. Some of these are warranted. Others are not. For those that are not, it is necessary to shine some light on them and hopefully readjust potentially faulty thinking. It is hoped that clearing up some of these issues that may be skewing your understanding of service members may make it easier for you to work with veterans.

All-Volunteer Military: Though there is still the Selective Service, which actively identifies individuals for the Draft should the need arise, there are no “draftees” currently serving in the military. The Draft has been out of commission since 1973. All current US Military members enlisted at their own free will, conquering the arduous enlistment process and clearing all the rigorous specifications (USA.gov, 2017).

Political Mono-Partisan: It seems that many view members of the military as being a part of the conservative or Republican party. This is not necessarily true. Though research acknowledges that military members and veterans slightly favor conservative beliefs, there is still a large percentage of veterans that maintain progressive or liberal views, as well. Veterans belong to an incredibly diverse array of demographics and backgrounds, and have a variety of political affiliations (Newport, 2009).

Humans, not robots: Ingenuity, thinking out of the box, following instincts is highly encouraged within the military, and development of such skills begins during the initial training, and continues throughout the military experience. Veterans do not just blindly follow orders. Veterans prepare, coordinate, assess, complete, and when necessary, question. However, veterans also recognize a purpose greater than themselves, and will do whatever is necessary. And as always, the mission comes first.

Not stupid: The complex initial testing to enlist in the military aside, veterans strive to make themselves better and more capable. This is done for individual value and sense of worth, but also for the betterment of the unit and to increase its abilities to assist those we are fighting with (Military.com, 2014).

War is missed, but not enjoyed: War is part of the job. In fact, one could easily argue that it is the job. When service members are not in combat, they are preparing for it. Though combat can bring about thrills, adrenaline, and excitement unlike any other (potentially on a manic level), there isn’t a veteran out there who hasn’t experienced fear at the thought of going to war (Davis, 2012).

Veterans are not violent: They are capable and ready for violence, true. But that is not to say all veterans are prone to violence. For the most part, those in the military do not wish to harm others. War is hell, and can create extremely stressful and chaotic circumstances. The result is typical of the environment they are in. It is human nature to ensure one’s own continued survival. When in combat, situations might necessitate action. Those same actions are not glamorized or romanticized. Rather, they are typically the material that makes up the veteran’s nightmares and regrets and that is carried throughout the veteran’s life. Though it is easy to pass judgement, please remember that there is a world of difference between being there and watching it on television (Davis, 2012).

Section III. Uniform Code of Military Justice

The Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), is the foundation of military law in the United States. It was established by the United States Congress in accordance with the authority given by the United States Constitution in Article I, Section 8, which provides that “The Congress shall have Power… To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval forces (UCMJ, 2008).” http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/ucmj.htm

UCMJ exists separate from the Unites States (US) Constitution. Military members “rights” are not as extensive as civil rights because members of the armed services are bound by discipline and duty. UCMJ is the only form of “constitutional law” where individuals, whom serve in the armed forces, are subjected to “double” jeopardy which means individuals can be convicted by “civilian law” and “military law” for the same offense.

Discharges

There are seven types of discharge and two categories of due process: administrative and punitive. Administrative covers such military discharge as honorable, general, other than honorable (OTH), and entry level separation (ELS). Punitive covers bad conduct (BCD), officer discharge (dismissal), and dishonorable discharge.

Honorable Discharge: When a military member receives good or excellent rating for their service time.

General Discharge: When a military member receives a satisfactory rating and does not meet all expectation of conduct.

Other than Honorable: The most severe type of administrative due process. Examples include: security violations, misuse of violence, conviction by a civilian court system, or being found guilty of adultery.

Entry Level Separation: If an individual leaves the military prior to completing 180 days of service. These individuals are not recognized by their state or federal government as “veterans.”

Bad Conduct Discharge: Only passed on to enlisted military member and is processed through court martial. This due process often comes with military prison time.

Officer Discharge: Because commissioned officers cannot receive a BCD or dishonorable discharge nor can they be reduced in rank, they receive a dismissal notice. This notice equates to a dishonorable.

Dishonorable Discharge: When a service member’s actions are considered reprehensible. Examples are murder, sexual assault (adult or minor), and child abuse or maltreatment. Individual’s whom receive such punitive action are not allowed under Federal law to own or possess a firearm and forfeit all military and veteran benefits.

The UCMJ was enacted by Congress in 1950. The purpose of the UCMJ was to establish a set of standards that outline procedure, substantive criminal law, and procedural safeguards. Prior to the UCMJ each system of military (Navy, Airforce, Army, and Marine Corps) established their own form of law known as Articles of War. The UCMJ united all systems of law developed by individual entities to ensure that military members accused of violating a “law” were subject to the same administrative or punitive charges and procedural rule(s) (UCMJ, 2008).

The UCMJ provides three levels of court systems known as court-martials (general, special, and summary). General court martial handles the more serious offenses and is similar to civilian trial courts. Special court martial handles intermediate level offenses. Special court martial impose such sentences like: six months of confinement (an individual is restricted to barracks, ship, or base movement only and for a certain amount of time allowed for personal reasons), forfeiture of pay, reduction in rank, and bad-conduct discharge. A summary court martial is issued by a commanding officer who handles minor offenses. The maximum penalties include confinement for one month, forfeiture of two-thirds of a month’s pay, and reduction in rank.

Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) hear all cases involving death, punitive discharge (bad conduct, dismissal, or dishonorable), or imprisonment for a term of one year or more. Each branch of service has their own CCA judges and a CCA typically involves a panel review of three judges. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces (USCAAF) is the highest civilian court which is responsible for reviewing the decision of all military courts. Any case(s) where the death penalty is imposed are forwarded by the judge advocate to the USCAAF.

Additional information can be found at the below links.

- https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/Military_Law/pdf/background-UCMJ.pdf

- https://www.jagcnet.army.mil/Sites/jagc.nsf/0/EE26CE7A9678A67A85257E1300563559/$File/Commanders%20Legal%20HB%202015%20C1.pdf

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZrapxpNMwhQ

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6zFbTihfEk

- >https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7NDiigSOI2A

Key Words

Uniform Code of Military Justice, court martial, court of appeals, dishonorable, honorable, other than honorable, entry level separation, bad conduct, general, officer discharge

Section IV: Family Life

Throughout this chapter, the intricacies of military culture, the military’s own unique judicial system, and the differences between the various military branches has been discussed. A closer look at the day-to-day events and family life is appropriate. Though it may be hard to believe, day to day life within the military is not too different from civilian life. There’s a job to be done, a daily routine to follow, and outside responsibilities that need attention. Bills, expenses, debt, school, professional development, and goal-setting are part of the life as well. Service members have hopes, dreams, and desires much like anybody else. They also have families. This section will review some more specific information regarding the family life of service members and veterans.

Family life within the military can be successful and rewarding. Extra levels of support and protection are in place to ensure family life stays as consistent as possible and every opportunity of success is offered. Alternatively, it can also be a very precarious environment. We’ve been at war for a generation now; the young men and women currently fighting overseas could be as young as two or three years old when airplanes collided with the World Trade Center nearly 16 years ago. It’s understandably hard to maintain stability within a relationship when the knowledge that your wife or husband, the father or mother of your children, could be called upon to go overseas and potentially never come home. That knowledge is something that lingers overhead like the worst of storm clouds, and adds tension to relationships that already come with their own intrinsic difficulties. Relationships are tough. Even more so when added stressors are brought to the forefront by the daily challenges and risks that being part of the military can bring.

Military Spouses and Dependents

Spouses and Dependents of service members are an integral part of military life. It is certainly within the realm of possibility to have both service members with spouses and children, or with families with multiple service members. In fact, if you’d reviewed the pay scales previously noted in this chapter, you might have noticed that service members are awarded additions to their paycheck for each dependent they have. These funds are increased by a fair amount when on deployment in support of combat operations overseas (Military Benefits, 2017).

It’s important to remind you that the mission always comes first. Always. Men and women who wear the uniform are called upon to serve their country wherever necessary, and under any circumstances (within reason). When that call goes out, it’s answered. However, it’s important to note that the military is not in the habit of leaving dependents without their beneficiaries, at least without a plan. Each branch of the military has supportive elements in place for service members and their dependents. The military understands an individual cannot perform to their full potential whilst being concerned with what is happening with their wife, husband, or children at home. With that said, service members are required to have a plan in place for their dependents should that call be made. Who is going to take care of your dependents? For how long? How are the finances being taken care of? What happens when crises occur? These are just basic questions that need to be answered for the plan to be accepted. And once the plan is made, it can rarely be deviated from (Duttweiler, n.d.).

These plans are crucial. In fact, service members with dependents might be deemed as “non-deployable” without such plan in place, and may be blocked from participating in deployments. Though this may seem a quick and easy way to avoid heading to combat, it’s not quite that simple and could result in UCMJ disciplinary action up to and including discharge from the military. To conclude this matter, a service member cannot deploy with his brothers- and sisters-in-arms unless a plan is in place for his dependents, and to not be deployable is essentially a taboo within the military and can be punishable by discharge. This rule applies in households with one service member involved. In families when both spouses are service members, this rule applies doubly so: each service member must come up with a plan as mentioned earlier, and must also include the scenario of both service members being deployed at the same time. The mission does come first, but that does not mean the military is disinterested in the safety and well being of its members’ spouses and children (Duttweiler, n.d.).

Deployment Cycles

As already mentioned, the United States has been at war for quite some time. The military has adjusted its own tactics and most units within the military are on a specific deployment cycle. Before the specifics of such cycle is covered, it should be noted that there are several supportive-based units within the military that are not necessarily part of this cycle. Not all service members are responsible for conducting combat operations. Some, in fact, are exempt from these rotations, and are strictly devoted to other tasks.

A variety of units within each branch of the military are devoted to training; their overall mission is to train the next generation of soldiers, sailors, marines, or airmen. In a rotation that runs consistently throughout the year, new service members hoping to earn the right to serve in the military are cycled in and out, and either successfully join the ranks of their respective branches, or do not and either fail, quit, or are rejected.

Additionally, some units within the military are tasked with operating designated training zones and their mission is to prepare units by conducting combat-related training prior to deployment. Fort Polk, Louisiana’s Joint Readiness Training Center (JRTC), and Fort Irwin, California’s National Training Center (NTC) and a variety of others, for example, host year-round wargames (for lack of a better term) with a variety of different units from all branches of the military to ensure they are as ready as can be for any scenario they might face whilst in combat (U.S. Army, 2014).

Another example are the various support units that keep the military running. It takes a large host of men and women to keep these efforts in line and working smoothly. The military, believe it or not, is an incredibly well-oiled machine. This is not achieved by accident. Many service members and civilian contractors are in place to keep things running smoothly.

The rest of the men and women serving in the military who are not part of the above examples typically operate as part of a deployment cycle. These units train independently, with other units, at the training facilities such as NTC or JRTC mentioned above, and even with other militaries from allied nations. This occurs for a set amount of time, and concludes with a deployment in support of combat operations overseas. These deployment cycles vary in length between units and branches of the military. And while some units within the military have advanced training and can be deployed to combat zones in as little as 72 hours, such deployments are typically scheduled months or years in advance. This means that, for the most part, current deployments are usually not a surprise. They obviously are in the event a new conflict occurs. This is why readiness is such a crucial aspect of military life (Pincus, House, & Adler, n.d.).

Divorce Rates

There was a time when divorce rates were significantly higher in the military. A fairly large spike in divorce rates occurred in the early 2000’s shortly after the war on terrorism saw hundreds of thousands of service members deploy in support of combat operations overseas. A study posted in the Huffington Post found that of the 462,444 military marriages that occurred between 1999 and 2008, those that occurred prior to the attacks on September 11, 2001 “were 28 percent more likely to divorce within three years of marriage if one or both spouses experienced a deployment to Afghanistan or Iraq that lasted at least one year” (Military divorce risk, 2013, para. 2).

As mentioned earlier, it seems this would not remain consistent. The same article suggested that those who married after 9/11/2001 had a lower divorce rate, suggesting that perhaps they knew what they were getting into and expected frequent stints of being away from one another. This decline in divorce rates amongst service members continues according to this article on Military.com, and further suggests that not only have military families grown accustomed to frequent deployments and stints of separation, but have also weathered the storm, as deployments are not happening in quite as rapid succession. In fact, divorce rates have nearly returned to their pre-9/11 rates (Philpott, 2012).

Section V. Health Related Concerns

In 2008, The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) introduced a new mental health handbook that provides guidelines for VA hospitals and clinics across the US. The new handbook specifies exactly what mental health services VA hospitals and clinics are required, by federal law, to offer all veterans and their families (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2014).

These guidelines include the following mental health requirements:

- Focus on Recovery: This approach requires the focus on individual strengths, a strength base approach.

- Coordinated Care for the Whole Person: VA workers collaborate to provide health care for each veteran to give safe and effective treatment.

- Mental Health Treatment in Primary Care: Each VA clinics uses Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs) manage the Veteran’s healthcare. A PACT is a medical team that includes mental health experts.

- Mental Health Treatment Coordinator: Mental Health Treatment Coordinator (MHTC) provide specialty mental health. The MHTC is goal oriented, providing individual or group care.

- Around-the-Clock Service: Mental health care is to provide seven days a week, 24 hours a day. If a VA facility does not offer such service, they are required to provide service through non- VA medical clinics.

- Care that is Sensitive to Gender & Cultural Issues: VA requires each PACT team to receive training regarding military culture, gender differences, and ethnicity.

- Care Close to Home: More VA clinics are opening in rural areas. Mobile clinics are becoming available. The VA is collaborating with community services to provide a larger scope of health services.

- Evidence-Based Treatment: Evidence-based treatments (EBT) are interventions backed by research to provide effective care for multiple health concerns. Each mental health team receives training on current EBT’s to ensure the best updated care is being offered.

- Family & Couple Services: In many cases veterans and their families/guardians also require treatment(s): family therapy, marriage counseling, grief counseling, drug addiction, anger management, etc.

Research provided by the VA (2014) suggests, the following mental health concerns rank the highest among veterans; posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, substance abuse, traumatic brain injury (TBI), suicide, chronic pain, and sexual assault. Social workers that work with military members and/or families should be familiar with each issue listed.

The VA (2014) defines these mental health concerns as follows:

- PTSD occurs after an individual has experienced, witnessed, or viewed a traumatic event. Symptoms may include relieving the event, avoiding places or things associated with the event, an increase of negative thoughts and emotions, feeling numb, and/or tense (hyperarousal) (Litz, 2009).

- Depression disorder interferes with one’s personal life, daily routine, and normal functioning. These symptoms do not pass over a short period of time (Lapierre, 2007).

- Substance use disorder (SUD) is identified as the tolerance to drink greater amounts of alcohol over time, inability to stop drinking or use of drugs, and withdrawal (feeling sick when trying to stop drinking or using drugs) (Bennett, 2014).

- Traumatic Brain Injury occurs when a person experiences a blow to the head or a joggling of the brain. People who experience TBI often experience a change in consciousness, disorientation, loss of memory, and confusion. Most TBI’s occur during “combat” conditions (Hoge, McGurk, Thomas, et al., 2008).

- Suicide is behavior which actively seeks self-destruction. Such behaviors are often provoked by the feeling/emotion(s) of loss or hopelessness (Jakupcak, Cook, Imel, et al., 2009).

- Chronic pain is pain that last for six or more months and limits daily activities (work, depressed mood or increase anger, sleep disturbance, withdrawal from family or friends, or hard to participate in physical activities). Chronic pain is different from acute pain because it last beyond the healing of an injury (Brandt, Goulet, Haskell, et al., 2012).

- Sexual assault is intentional sexual contact utilizing force, physical threats, abuse of authority, acts of adultery, acts that violate the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), or when a person is unable to consent to sexual activity (Burns, Grindlay, Grossman, et al., 2004).

Social workers who work within the VA follow a mission statement that maximizes health and well-being of all military members, families, and communities through the use of EBT. Their vision is leading by example, setting high standards, and establishing innovative psychosocial care and treatment.

“The values established by the VA and UCMJ suggest, that all social workers who serve military members, veterans, military communities, and their families must advocate for optimal health care by respecting the dignity and worth of the individual, understanding military socio-cultural environments, empower veteran’s as the primary member of their PACT, respect the individual role and expertise of the veteran, focus on the needs of at-risk-population within military communities/families, promote learning (fostering knowledge, enhances clinical social work practice, advances leadership, and focuses on administrative excellence), exemplifies and models professional and ethical practice, and promotes conscientious stewardship amongst organizational member(s) and within community services” (VA, 2014).

The Veterans Bureau General Order (1926) was the first to establish a social work program inside the VA. This program allowed 14 social workers who were predominately highered to work on psychiatric and tuberculosis victims. From 1926 to 1946, Irene Grant Dalymple, pioneered the social work medical environment into the current mental health settings seen in today’s VA. Her involvement set the stage for the current social work programs that were instrumental in establishing health care systems adapted by the VA after World War I. Prior to WWI, social work services were contracted outside the VA to non-military service type facilities. Due to her contributions, the VA now provides services of health care, mental health, group and family care plans, vocational and psychosocial rehabilitation, and programs to assist with adjustment/coping skills to be reunited back into civilian society.

Today, social workers working in the VA have evolved into a professional service responsible for the treatment of military members, military communities, and family members. These responsibilities include but are not limited to treatment approaches which address individual social problems, acute/chronic conditions, terminal patients, and bereavement. “VA social workers ensure continuity of care through the admission process, evaluation procedure, treatment, and follow-up treatment” (VA, 2017, July 24, para. 8). All continuity of care must include discharge planning and providing case management services.

Populations of veterans needing services are: homeless, the aged, HIV/AIDS patients, spinal cord injury, Ex-Prisoners Of War, Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans, Vietnam and Persian Gulf Veterans, WWI and WWII Veterans, Korean War Veterans, Active/Inactive/Reserve/National Guard members, and their families.

Social workers help coordinate program such as:

- Community Residential Care (CRC)

- Financial or housing assistance

- Getting help from such agencies as Meals on Wheels

- Applying for benefits (health care, vision, optical, mental health, dental, financial, educational, and more)

- Ensuring that members of the PACT know your concerns and decisions

- Arranging for respite care

- Marriage or family counseling

- Moving into an assisted living or nursing home

- Bereavement

- Substance Use Disorder prevention or treatment

- Abuse, mistreatment, being taken advantage of, maltreatment, or need of a guardianship

- Parents who feel overwhelmed with child care

- Parents or spouses dealing with failing health concerns

- Mental health or medical needs

- Need direction of services or other unspecified needs

How can Social Workers help Veterans with problems and concern?

VA social workers have experience in assessment, crisis intervention, high-risk screening, discharge planning, case management, advocacy, education, and psychotherapy. Social workers help with all types of services, plus many more. The VA social workers motto: “If you have a problem or a question, you can ask a social worker. We’re here to help you!” (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017, July 24, para. 13).

Key Words

Uniform Code of Military Justice, Veteran Administration (VA), Evidence-based treatment (EBT), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), traumatic brain disorder (TBI)

Section VI: Resources for Veterans

It could easily be argued that as long as our nation is involved in conflicts overseas, there will continue to be great efforts to ensure the men and women involved in those conflicts are well taken care of when they return home, and even more so when they retire their uniform and exit the military. There are many available services for veterans, yet access can be challenging. Veteran services are largely area-specific. Web links to state and federal programs will be included in each of the following subsections, but to learn about all the services available will require some searching on your part.

The Department of Veterans Affairs

This is the largest source of support for veterans. The Department of Veterans Affairs is a federal agency within the United States government whose purpose is to fulfill President Lincoln’s promise “[t]o care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan” by serving and honoring the men and women who are America’s veterans” (United States Department of Veterans Affairs, (2015). When it comes to providing services to veterans, the race starts here. This agency has the incredible burden of assisting with millions of pensions, service-related disability claims, education benefits, life insurance claims, healthcare benefits, and much, much more. If you’ve been paying attention to the news over the past several years, it’s no surprise to hear they are struggling to meet the ever-growing needs of service members and veterans. Regardless, the VA is the primary service provider for veterans. For a generalized look at what this organization can provide, check out their website’s benefits section here. Additionally, for a look at state-funded veteran services, take a look here.

County VA offices and VSOs

Like the federal Department of Veterans Affairs, there are also County Veteran Affairs offices. While they are directly linked to the federal VA, they are funded by the local county and usually employ Veteran Service Officers (VSOs). These VSOs assist veterans in completing the rigorous paperwork involved in applying for benefits. And since they are typically locally funded, they likely have access or knowledge of local programs, grants, and services that are not directly administered by the VA. A listing of VSOs can be found here.

Mental Health

In addition to Department of VA offices and County VA offices, many larger cities often have Community-Based Outpatient Clinics (CBOCs). Though these CBOCs are often primarily utilized to provide veteran health care, they are typically staffed by one or more Licensed Masters level Social Worker (LMSW), Licensed Professional Counselor (LPC), or Psychologists. Vet Centers are also available in select cities. Vet Centers are connected with the VA, but typically operate independently with the sole purpose of providing individual- and group-therapy to veterans in their identified catchment area or area of responsibility. For smaller communities that may not have a CBOC or Vet Center, the VA likely has an agreement or contract setup with a local private agency, though this is not always the case. It’s a safe bet that the smaller the city, the more likely a veteran will have to travel to get access to veteran-specific services. Utilizing the Hospital Locator here is a quick and effective way at finding local VA mental health services. Take a look!

Veteran Suicide

One last section is necessary when talking about veterans and mental health struggles. Sadly, veteran suicide rates are high. According to a report posted in the Military Times, roughly twenty veterans commit suicide every day, and despite making up only 9% of the population, represent 18% of all American suicides.

References

Branches of Service:

United States Air Force. http://www.af.mil/

United States Army. https://www.army.mil/

United States Coast Guard. https://www.uscg.mil/

United States Marines. http://www.marines.mil/

United States Navy. http://www.navy.mil/

Adams, R. S., Larson, M. J., Merrick, E. L., & Wooten, N. R. (2012). Military combat deployments and substance use: Review and future directions. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 12(1), 6-27.

Belmont, J. P., Burks, R., Knox, J., Orchowski, J., Owens, D. B., & Scher, L. D. (2011). The incidence of low back pain in active duty United States military service members. Journal Global Research and Reviews, 36(18), 1492-1500.

Bennett, A. S., & Golub, A. (2014). Substance use over military-veterans life course: An analysis of a sample of OEF/OIF veterans returning to low-income predominately minority communities. Addictive Behaviors, 39(2), 1-13. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3849200/pdf/nihms503658.pdf

Brandt, C., Goulet, J., Haskell, G. S., Kerns, R., Mattocks, K., & Ning, Y. (2012). Prevalence of painful musculoskeletal conditions in female and male veterans in 7 years after returning from deployment in operation enduring freedom/operation Iraqi freedom. Clinical Journal of Pain, 28(2), 163-167.

Bray, R. M., Hourani, L. L., Lane, M. E., & Williams, J. (2012). Prevalence of perceived stress and mental health indicators among reserve-components and active-duty military personnel. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1213-1220.

Burns, B., Grindlay, K., Grossman, D., Holt, K., & Manski, R. (2004). Military sexual trauma among U.S. service women during deployment: A qualitative study. American Journal of Public Health, 104(2), 345-349.

Bushatz, A. (2016, April 22). Military divorce rate continues slow but steady decline. Military.com. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/daily-news/2016/04/22/military-divorce-rate-continues-slow-but-steady-decline.html

Cernal, S. (2015). Sexual assault and rape in the military: The invisible vctims of international gender crimes at the front lines. Michigan Journal of Gender and Law, 22(1), 207-241. Retrieved from http://repository.law.umich.edu/mjgl/vol22/iss1/5/

Conard, P. L., Allen, P. E., & Armstrong, M. M. (2015). Preparing staff to care for veterans in a way they need and deserve. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 46(3), 109-118.

Davis, J. K. (2012, June 15). How do military veterans feel when they return home from combat? Forbes.com. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2012/06/15/how-do-military-veterans-feel-when-they-return-home-from-combat/#350800923e1e

Department of Defense Core Values. (2009). Military Leadership Diversity Commission , 1-2. Retrieved from http://diversity.defense.gov/Portals/51/Documents/ResourcescCommission/docs/Issue^20Papers/Paper%2006%20-%20DOD%20Core%20Values.pdf

Department of Veterans Affairs Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) Program. (2016, October 1). Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/ssvf/docs/SSVF_ProgramGuideOctober2016_Final.pdf

Duttweiler, R. (n.d.). What the heck is an FRG? Military.com. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/spouse/military-life/military-resources/what-the-heck-is-an-frg-family-readiness-group.html

Golden, C. (Ed.). (2011). 2d Stryker Cavalry Regiment: “Second Dragoons”. Newton, MA: 2d Cavalry Association.

Hoge, C. W., McGurk, D., Thomas, J. L., Cox, A. L., Engel, C. C., & Castro, C. A. (2008). Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. New England Journal of Medicine, 358, 453-463. Retrieved from http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa072972

Jakupcak, M., Cook, J., Imel, Z., Rosenheck, R., & McFall, M. (2009). PTSD as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(4), 303-306. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/144c/5037d6315c0a0e4449a9c6e26ffb07af8b21.pdf

Junger, S. (2014, May 23). Why veterans miss war [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGZMSmcuiXM

Lapierre, C. B., Schwegler, A. F., & LaBauve, B. J. (2007). Post-traumatic stress and depression symptoms in soldiers returning from combat operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 933-943. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/132d/bc8d3189c61aad88ba08466aadcd02be9e1e.pdf

Ledoux, M. (2014, October 27). Marine Corps silent drill platoon stun a packed arena [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1a5qbzpWTcY

Lifeline for Vets.com. (2017). Veteran service officers. Retrieved from https://nvf.org/veteran-service-officers/

Litz, T. B., & Schlenger, E. W. (2009 Winter). PTSD in service members and new veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars: A bibliography and critique. National Center for PTSD, 20(1), 1-8. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/newsletters/research-quarterly/v20n1.pdf

Military Benefits. (2017). 2017 Military Pay Charts. Retrieved from http://militarybenefits.info/2017-military-pay-charts/

Miltary.com. (n.d.)a. Deployment: An overview. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/Deployment/deployment-overview.html

Miltary.com. (n.d.)b. Military ranks and insignia at a glance. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/join-armed-forces/military-ranks-insignias.htm

Military.com. (n.d.)c. State veteran’s benefits. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/benefits/Veteran-state-benefits-state-veterans-benefits-directory.html

Military.com. (2014, May 14). 80% of military recruitments turned down. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/join-armed-forces/2014/05/14/80-of-military-recruitments-turned-down.html

Military divorce risk increases with lengthy deployments. (2013, September 03). Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/09/03/military-divorce_n_3861441.html

National Center for PTSD, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2012, April 6). Active duty vs. reserve or National Guard. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/Vetsinworkplace/docs/em_activeReserve.html

Newport, F. (2009, May 25). Military veterans of all ages tend to be more Republican. Gallup.com. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/118684/military-veterans-ages-tend-republican.aspx

Philpott, T. (2012, April 12). Military marriages show a surprising level of resilience. Stars and Stripes. Retrieved from https://www.stripes.com/news/military-marriages-show-a-surprising-level-of-resilience-1.174275#.WWvN7YQrKM9

Pincus, S. H., House, R., Christenson, J., & Adler, L. E. (n.d.). The emotional cycle of deployment: Military family perspective. Military.com. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/spouse/military-deployment/dealing-with-deployment/emotional-cycle-of-deployment-military-family.html

Quora. (2013, July 15). Top 50 military slang words and phrases. Military1.com. Retrieved from https://www.military1.com/army/article/403808-top-50-military-slang-words-and-phrases/

Schumm, W. R., Gade, P. A., & Bell, D. B. (2003). Dimensionality of military professional values items: An exploratory factor analysis of data from the Spring 1996 Sample Survey of Military Personnel. Psychological Reports, 92(3), 831-841.

Shane , L., III, & Kime, P. (2016, July 7). New VA study finds 20 veterans commit suicide each day. Military Time. Retrieved from http://www.militarytimes.com/story/veterans/2016/07/07/va-suicide-20-daily-research/86788332/

Sion, L. (2016). Ethnic minorities and brothers in arms: competition and homophily in the military. Ethnic & Racial Studies, 39(14), 2489-2507. doi:10.1080/01419870.2016.1160138

Air University (AU). (n.d.). Uniform Code of Military Justice. http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/ucmj.htm

United States Army, Combined Arms Center. (2014, July 8). Combat Training Center Directorate (CTCD). Retrieved from http://usacac.Army.mil/organizations/cact/ctcd

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (n.d.). Explore benefits that help veterans thrive. Retrieved from https://explore.va.gov/

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015, August 20). About VA. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/ABOUT_VA/index.asp

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2016, November 4). Suicide prevention. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/Suicide_prevention/

United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017, July 19). Mental health. Retrieved from https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/

United States Department of Veteran Affairs. (2017, July 24). What VA social workers do. Retrieved from https://www.socialwork.va.gov/socialworkers.asp

USA.gov. (2017, August 8). Selective service. Retrieved from https://www.usa.gov/selective-service

Veterans Authority. (2017). What is a veteran? The legal definition. Retrieved from http://va.org/what-is-a-veteran-the-legal-definition/

Vetfriends.com. (n.d.). Military structure. Retrieved from https://www.vetfriends.com/military_structure/

Wolfe, T. (2012). Military camaraderie in the civilian world? Military.com. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/military-transition/employment-and-career-planning/military-camaraderie-on-civilian-job.html

Zarembo, A. (2015, October 7). Study: tool can identify soldiers most likely to commit violent crimes. Military.com. Retrieved from http://www.military.com/daily-news/2015/10/07/new-tool-can-identify-soldiers-most-likely-commit-violent-crimes.html

Ziezulewicz, G. (2009, June 12). Unique camaraderie forged by troops downrange lasts far beyond deployment. Stars and Stripes. Retrieved from https://www.stripes.com/news/unique-camaraderie-forged-by-troops-downrange-lasts-far-beyond-deployment-1.92442#.WWvTTYQrKM9