7 PRESENT

Sharing What You’ve Learned

In earlier chapters we discussed how to identify a research topic and how to focus in on specific questions that we hoped to answer. Then we discussed ways to search for, organize, and evaluate information that would help to answer those questions. Now it’s time to think about the best way (or ways) to present the information.

Academic research can be difficult, but you’re not alone! Research is a conversation between many different “voices” that each contribute a unique perspective on a topic. There are many ways that you can use that conversation to help improve your understanding of a topic and discover what you have to say about it and how to participate in the conversation. Watch the video nform Your Thinking: Episode 1 – Research is a Conversation as you consider the many ways in which information is presented.

OKStateLibrary (2016) Inform Your Thinking: Episode 1

The PIO 101 learning outcome that aligns with PRESENT is:

Students will recognize the diversity of our world and demonstrate their ability to engage in thoughtful, respectful, ethical academic-level discussions that contribute to campus and community

In this chapter:

- PRESENT: Understanding and Skills

- Processing What You Find

- Summarizing

- Writing a Thesis Statement

- Creating an Outline

- Choosing How to Share Your Information

- Audience

- Written Ways to Share What You’ve Learne

- Traditional Paper

- Thesis/Dissertation

- Scholarly Journal Article

- Blog/Tweet/Other Social Media

- Spoken Ways to Share What You’ve Learned

- Class Presentation/Speech

- Conference Presentation or Poster Session

- Audiovisual Ways to Share What You’ve Learned

- PowerPoint/Prezi/Other Presentation Software

- Images

- Song

- Video

- Your Role in Creating and Sharing Information

- Wider Connections

- Learning Activities & Resources

During the research process, at times it can feel as if you are just collecting what others have written or said, and that your presentation is just going to repeat what is already known on the topic. While this may be true for introductory-level papers, once you know a little more about your topic, you can begin putting different pieces of information together—this is called synthesizing what you’ve discovered. As you gain new knowledge, you can begin to draw your own conclusions about the topic you are studying. Once you share these conclusions you will have created new information.

Before the advent of online tools, publishing your new information was difficult and often expensive. It was hard to reach a large audience because of the physical limitations of producing and distributing paper copies of publications. Now anyone can publish anything and make it available to the entire Internet-connected world in a matter of seconds. This means that you have a great opportunity to share your ideas and to communicate with people around the world who are interested in similar topics. It also means that you have to carefully consider what you publish because anyone, even an unintended audience, can find what you’ve published.

In addition to being able to share information freely, you also have access to tools to create and edit audio and video materials that were prohibitively expensive to create or adapt not too long ago. You can now share more interactive and engaging material with a wider audience than ever before. This is a great opportunity and a great responsibility— use it wisely!

PRESENT: Understanding and Skills

Individuals adept in the PRESENT pillar can apply the knowledge they have gained. They can present the results of their research, synthesize new and old information and data to create new knowledge, and disseminate their work in a variety of ways.

They understand:

- The difference between summarizing and synthesizing,

- That different forms of writing/presentation style can be used to present information to different communities,

- That data can be presented in different ways,

- Their personal responsibility to store and share information and data,

- Their personal responsibility to disseminate information & knowledge,

- How their work will be evaluated,

- The processes of publication,

- The concept of attribution,

- That individuals can take an active part in the creation of information through traditional publishing and digital technologies (e.g. blogs, wikis)

They are able to:

- Use the information and data found to address the original question,

- Summarize documents and reports verbally and in writing,

- Incorporate new information into the context of existing knowledge,

- Analyze and present data appropriately,

- Synthesize and appraise new and complex information from different sources,

- Communicate effectively using appropriate writing styles in a variety of formats,

- Communicate effectively verbally,

- Select appropriate publications and dissemination outlets in which to publish if appropriate.

Real-life Scenario — Revisit

Remember Hunter from the IIDENTIFY chapter? He is a a gamer who plays Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games (MMORPGs) and has done a lot of work since the last time we saw him. His research supports his thesis statement and he’s got something to say. Now he needs to figure out how to say it.

Processing What You Find

In many or even most cases, during the process of finding a variety of information sources, you’ll begin to develop an answer to your research question. Even if you feel that you’ve already found the proof you need to support your thesis, it is still important to review the information and data you have to be sure you’re clear about what it is (and isn’t) telling you. Be careful not to let your own opinion lead you into a misinterpretation of your sources.

One useful way to consolidate the information you’ve found is to summarize what you think it says, and then find a definite source for each specific item in your summary. In the IDENTIFY chapter you were presented with an exercise that included four questions:

- What do you already know about your topic?

- What do you want to know about your topic?

- How will you find information on your topic?

- What have you learned about your topic?

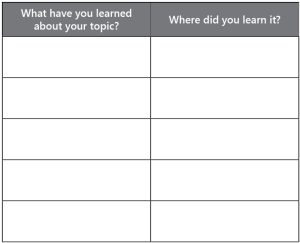

Now you can answer the fourth question—what you’ve learned about your topic. And you should ask yourself another question: Where did I learn the information I found? Make a list of all the sources you used and think about which ones you find to be the most reliable or useful. Depending on where and how you present your findings, you may be called upon to defend your sources, so it pays to be prepared for this. and this list will also prove useful when you need to cite a specific bit of information in your works cited page.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 7A provides one way to help you organize what you have learned about your topic and where you learned it.

Summarizing

Another way to organize and share your information is to summarize it in paragraph form. Summaries are shorter than the original text and provide a broad overview, not specific details. Summarizing your information provides an added benefit–what you write in the summary can often become part of your final product.

Summarizing involves putting the main idea(s) into your own words. To summarize information, first read the information, then ask yourself: What is this text about?

Write a short answer in full sentences – not in one or two words. Your summary should cover the main point and key ideas. USE YOUR OWN WORDS! Don’t look back to “borrow” words from the original text.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 7B provides practice summarizing.

Orally summarizing your findings (saying them out loud) to a friend, classmate, or teacher is an excellent way to confirm your mastery of the topic. While the means of summarizing can vary, the key at this point is to make sure you understand what you’ve found and how it relates to your topic and research question.

Writing a Thesis Statement

In the IDENTIFY chapter, you were introduced to the idea of a thesis–a potential answer to your main research question. The information you have gathered for your research topic should hopefully answer your research questions and you can now form a proper thesis statement. A good thesis statement not only introduces your reader to the topic, but also helps you to focus your argument or position.

Your thesis statement should be no more than three to five sentences in length, but is made of 3 parts:

- First part: Describe the main issue of your broader topic upon which you will focus (*1)

- Second part: Make a statement, claim or argument (take a position on your topic) (*2)

- Third part: Propose a solution or a call to action (*3)

Using Hunter’s research example from the IDENTIFY chapter, let’s create a thesis statement to support his argument that MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games) are good for American Society:

MMORPGs have been demonized in American society as a waste of time and childish.(*1) Online games are more sophisticated than critics acknowledge and online gamer communities provide supportive social networks.(*2) MMORPGS have been shown to increase creativity, enhance social connections and are a productive use of gamers’ time. American society needs to re-examine their stance on MMORPGs.n(*3)

Things to remember about thesis statements:

- A thesis statement is a tentative answer to your research question.

- Thesis statements must make a claim or state an argument.

- The thesis should be debatable (must be something that people could reasonably have differing opinions about).

- The thesis statement should be narrow and specific.

- Thesis statements are not statements of fact, nor are they simply statements of opinion. They are a blend of both—opinion backed up by supporting facts.

- The key difference between an opinion statement and thesis statement is that a thesis statement expresses to the reader that the claim being offered has been thoroughly explored and is defendable by evidence.

- It’s a good idea to think about what the other side of the argument is when you are constructing your thesis statement.

Creating an Outline

Once you have come up with your thesis statement, you can further focus your thoughts by creating a research topic outline. Creating an outline allows us to organize all of the research we have conducted into a logical and informative structure. Outlines can help you figure out how to connect all of the ideas found during your research, and whether or not you have enough evidence to support the main points you want to make.

Conventions of the Research Topic Outline:

-

-

- Identify your Research Topic

- Outline the Main Headings of your argument

- Create Sub Headings as needed

- Include relevant Evidencefrom you research portfolio analyses to strengthen your argument

-

Start your outline by brainstorming and listing all of the ideas you want to include in your research paper. Next, start to organize all of those ideas by grouping related ideas together, arranging your ideas into main sections. Then express general ideas and subsections within each main section, try to get down to expressing specific ideas. Finally, include specific examples from your research to support your main and/or subpoints.

Now that you’re confident in your knowledge of your topic, you can formally answer your original research question when you present what you’ve found. Did your original thesis/hypothesis turn out to be true? If so, say so! If not, why not? Be sure you’re able to state specifics that prove or disprove your projections. Was anything a surprise? Do any of your findings suggest future research possibilities?

One of the most satisfying parts of doing research is having something to add to a topic’s base of knowledge. Think about what you found in relation to your original research question and compare it to all of the sources you examined on your topic. Did you discover something new? If your research involved experiments, you may have new results or data sets that others can use. Even if you didn’t generate new data, maybe you saw new connections between existing sources that no one has written about before. Think about this as you begin to put together the presentation of your findings, you may have something to share!

Choosing How to Share Your Information

The way you finally present your research findings is largely dependent on your original goals. If you were researching for a class project, it’s likely that the teacher provided you with fairly specific requirements and it would obviously be a good idea to stick to them.

Even if you did initially do the research for a class project though, you may find yourself in a situation similar to Hunter in the scenario below, wanting to share your work more widely. You’ve already done the work, so why not get all the benefit you can?

Some of the more common ways of presenting information are discussed below, but the descriptions of them are not exhaustive and remember that these are not nearly all of the options. In addition, you can often combine more than one method of presentation to highlight different elements of your findings or to reach multiple audiences.

Real-life Scenario Update

Back to Hunter. He has done a lot of work. His research supports his thesis statement and he’s got something to say. Now he needs to figure out how to say it. Hunter writes a 10-page paper starting with his thesis statement, followed by some facts from his research, and then briefly concludes that he has proved his point. He hands it in to his teacher and he’s finished. Except that he starts to feel like he just did an awful lot of work for an audience of one person. Who else might be interested and how might he reach them? How can he communicate his message in ways other than a straightforward paper? How can he get the most out of his effort?

Audience

Who you plan to share the information with affects how, when, and what you will present. If you’re presenting your findings in a paper that only your teacher will ever see, you will focus exclusively on what that teacher has asked for. When you’re presenting for a less well-defined audience however, you must imagine what they may already know (or not) about your topic, as well as what might interest them and what forms of presentation might be most appealing to them.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 7C can help you plan for your audience.

Consider how different audiences affect what you might or might not include in your presentation about your topic? How do they affect the ways you might choose to present the information?

Many times you will present to an audience composed of various groups or unknown groups (particularly if you’re posting the presentation online). If you’ve considered a number of different audiences and chosen the content and methods most likely to appeal to most of them, your chances of success will be higher than if you only include what is most interesting to you.

Written Ways to Share What You’ve Learned

Writing is the most established way to share your research findings. Benefits of writing include the ability to proofread, edit, and rewrite to get your presentation exactly right. Done skillfully, writing can hold your audience’s attention and effectively deliver information. Done poorly, it can confuse or bore your audience to the point that they stop reading. To avoid this second possibility, if at all possible, have someone read your writing before you give it to the final audience. Take constructive criticism to heart, so that your voice is clearly heard.

Traditional Paper

One of the most common ways to present research findings, especially for students, is in a short paper written as a class assignment. The way this type of paper is formatted is determined by the teacher, and is fairly straightforward. The goal is usually to demonstrate to the teacher that you have understood the topic and can draw some conclusions from what you’ve learned.

Thesis/Dissertation

At higher levels of education, you may be called upon to write a thesis paper or even a dissertation. At this point, you are entering the realm of high level professional or scholarly expertise, and will be expected to produce original ideas and the necessary supporting research to contribute to your field. The type of writing in theses and dissertations varies depending on the subject area, but generally these manuscripts are longer and more detailed than a traditional class paper. They also use more discipline-specific language, and can take several years to complete.

Scholarly Journal Article

Articles published in scholarly journals undergo a peer-review process (see the EVALUATE chapter) to ensure that they are reliable and significant additions to the literature on a topic. If you get to a point in your research where you feel you have a contribution that others could use, investigate the possibility of submitting an article for publication, especially if your research is relevant to your intended career. It can be difficult to determine which journal to submit your article to, so don’t hesitate to ask teachers, colleagues, or even the editor of the journal if your article’s content is appropriate.

Blog/Tweet/Other Social Media

A relatively new option for getting your information out to a wide audience is to use social media tools. If you have your own blog or website you can easily publish your findings for the entire world to see (getting people to actually look at it is another issue, with many possible solutions). You can also use Facebook, Twitter or other tools to let people know what you’re working on and to direct them to more detailed information that you’ve posted elsewhere online. While this may seem unusual, it is becoming more and more popular for researchers to share work online as it progresses, so that other interested parties can contribute and ask questions, making the final product more robust, whatever form it ends up taking.

Spoken Ways to Share What You’ve Learned

Presenting information orally might seem easier than writing or terrifying, depending on your experience and personality. Ideally you will be thoroughly prepared and able to clearly explain your findings, while also being able to respond effectively to unanticipated questions. It takes practice and a deep knowledge of your topic to do this—even the best speakers get flustered once in a while. Don’t be afraid to say you don’t know the answer and always offer to follow up on a question.

Class Presentation/Speech

As with the class paper, a class presentation is one of the first experiences most students will have with orally presenting their research. One great benefit of this type of presentation is that you will most likely receive detailed feedback on how well it was received and perhaps even get some suggestions on how to improve your delivery. Your fellow students will also be faced with the same task and can even provide this type of feedback before the actual presentation takes place.

Conference Presentation or Poster Session

As your expertise on a topic grows, you may want to reach a wider audience. You will also want to reach an audience that is interested in your topic. An excellent place to find this audience is at a professional conference in your field. Aside from the many other benefits of attending professional conferences, presenting at a conference will help you begin to make yourself known to other researchers in similar subject areas. Responding to audience questions will give you the chance to prove that you really know your material or, alternately, can point out gaps in your knowledge that may lead to new research opportunities. Poster sessions are a great way to get your feet wet, as your poster will be available for you to refer to and the atmosphere is not quite as overwhelming as standing in front of a full audience for a presentation.

Audiovisual Ways to Share What You’ve Learned

Visual images can have an immediate impact on how your audience reacts to and understands your presentation. Choose them wisely and use them at appropriate times!

PowerPoint/Prezi/Other Presentation Software

PowerPoint has been around long enough that most everyone knows it. For many purposes a slideshow that you speak over, or even a slideshow that is posted online for individual viewing, can succinctly get your point across. Newer presentation tools such as Prezi (prezi.com) use a similar underlying idea but enable you to create more dynamic presentations directly online. Keep in mind that in most cases, tools such as these are meant to accompany a speaker and to use them effectively takes forethought and practice.

Images

Images can be powerful tools to grab attention, condense information, and tell your story. Different types of images can be useful in different contexts. In an art class you may use reproductions of famous paintings or drawings, or images you’ve created on your own. In a business class, graphs and charts may be more appropriate. Just make sure the images you choose actually make your presentation more effective rather than distracting attention from your main point. If you are using other peoples’ images, be sure you are doing so ethically, including providing citations to the source of the images.

Song

Keeping your audience in mind, don’t be afraid to present your material in an unusual manner. If you can create a song (as one example), you may make your audience curious enough to stay around for more detailed information later!

Video

With the tools available now, it is possible to create a quality video product to present your information without extensive training or a lot of money. New online tools are constantly being introduced (and retired, unfortunately) which enable you to enter your content (words, images, video, etc.) and have it processed into a completed video in a short amount of time.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 7D can help you to think about different formats for your information.

When you finally do present/publish the results of your research, there are some things to think about in terms of what happens next.

What will you do with the information now that you’re finished with it? If you’ve written a paper for a class there may be only one copy. Do you save it and the associated notes you’ve made in case you need them later or do you throw it away once you get the grade? It can be difficult to project what may be useful in the future.

If you’ve published more widely, there are likely to be more copies, either physical or digital. Who is responsible for maintaining those copies? In a more formal situation such as a scholarly journal, the article will be maintained as part of the archives of that journal. (However, there are some questions about online-only journals. What happens if the journal goes out of business? Some journals have contingency plans for this, but not all.) If you’ve given a speech, do you keep the notes? If you’ve published on a blog, are you archiving the blog, or will it disappear once you stop using it? Even if you decide to save absolutely everything, unless you have a plan for organizing it, you may not be able to find a specific item when you need it.

Another consideration about what happens after your work is shared is what the reaction to it might be. This depends on the audience, but if you’ve created something really interesting or important, you may find that there is follow-up to be done. You might just be responding to comments on a blog posting or you could find yourself presenting your findings at conferences and continuing to develop your research on the topic. There may be negative feedback as well, and this is where thinking ahead about how you can support each of your arguments is important. Online, of course, there may be everything from kudos to spam and you’ll have to decide how seriously to take all of that feedback. As time goes by, you may find that your work is being cited by other researchers, which is a wonderful validation of your efforts.

Wider Connections

When you begin to share your own work, you gain insight into the processes of producing and publishing information, which will help you the next time you need to find sources for a research project. Now that you know what it took for you to produce information in a given format, you know what other creators had to do to produce their work. This can help you decide which sources will be most reliable and valuable for your own research.

Presenting your information is usually considered the final step in the research process. You tell the audience what you’ve found out and you go home. However, as we’ve seen, sometimes in the process of presenting or preparing to present, you uncover new questions and need to Identify that new information need. Or you may discover that what you thought was a reliable source was not so reliable and you need to Evaluate a little more. The research process is not linear, but a continuous cycle with various entry and exit points that change depending on your goals, topic, and methods. Ideally, for those who enjoy it, it never ends!

Learning Activities & Resources

Exercise 7A: What did you learn and where did you learn it?

In the left column, list what you have learned, bit by bit. In the right column, list where you found it. If it was found in more than one source, list them all and think about which one you find to be the most reliable or useful.

Exercise 7B: Practice Summarizing

First, read the following paragraph.

A penny for your thoughts? If it’s a 1943 copper penny, it could be worth as much as fifty thousand dollars. In 1943, most pennies were made out of steel since copper was needed for World War II, so, the 1943 penny is ultra-rare. Another rarity is 1955 double die penny. These pennies were mistakenly double stamped, so they have overlapping dates and letters. If it’s uncirculated, it’d easily fetch $25,000 at an auction. Now that’s a pretty penny. (Morton)

- What is the main point of the paragraph?

- What key ideas are important to understand the significance of the paragraph?

- Now, write one or two sentences that captures the main point and any other key ideas.

EXAMPLES—How does your summary compare?

- The text is about pennies. Does this include all of the key points necessary to understand the paragraph? This example is too short and is missing main kdeas.

- The 1943 copper penny is worth a lot of money. Copper was hard to get during the war so there aren’t many of them. The 1955 double die penny is worth a lot too. These pennies were stamped twice on accident. Is all of the information that is included needed to understand the original paragraph’s significance? There is too much unnecessary stuff, and the main idea is not clear.

- This text is about two very rare and valuable pennies: the 1943 copper penny and the 1955 double die penny. This example includes key information, doesn’t include unnecessary information, and is a complete sentence.

Exercise 7C: Plan for your audience

| AUDIENCE | WHAT MIGHT THEY KNOW? | WHAT PRESENTATION METHOD MIGHT MOST APPEAL? |

| Teacher of the class | ||

| Fellow Students | ||

| Experts at a conference | ||

| Your family at a holiday gathering | ||

| A group of elementary school students | ||

| A news reporter interviewing you | ||

| ADD YOUR OWN: | ||

| ADD YOUR OWN: |

Exercise 7D: think about different formats for your information

Take what you’ve learned about your topic and express it in the following formats.

- As a written paragraph, a 280 character tweet,

- As a Prezi.

- Try to draw a picture that clearly explains your findings.

Which of these seems most complete? Which seems most effective? Which seems most attention grabbing? Which was the hardest to do? Attempting this exercise might help you to make your decision about which format to use, although there are other things to consider first, particularly your intended audience.