3 PLAN

Developing Research Strategies

Even when a person knows their information need and knows what is available, they have to be able to locate information and data to fill those needs. A person who is information literate in the PLAN pillar can construct strategies for locating information and data.

The PIO 101 learning outcome that aligns with PLAN is:

Students will be able to develop strategies for accessing needed information.

In this chapter:

- PLAN: Understanding and Skills

- Selecting Search Tools

- So, how do you identify the best search tools?

- What to Search

- Database Research at Your Academic Library

- A Side Note About Library Catalogs and Discovery Interfaces

- Searching Databases

- Metadata

- Controlled Vocabulary

- Database Research at Your Academic Library

- How to Search

- Determining Search Concepts and Keywords

- Putting it All Together

- Learning Activities & Resources

PLAN: Understanding and Skills

Being information literate in PLAN includes:

- Understanding a range of searching techniques,

- Understanding the various tools and how they differ,

- Knowing how to create effective search strategies,

- Being open to searching out the most appropriate tools,

- Understanding that revising your search as you proceed is important,

- Recognizing that subject terms are of value.

There are also things you need to be able to do:

- Clearly phrase your search question,

- Develop an appropriate search strategy, using key techniques,

- Selecting good search tools, including specialized ones,

- Use the terms and techniques that are best suited to your search.

Real-life Scenario

Natalie is concerned about water pollution in Minnesota. As a member of the Fond du Lac Band of Ojibwe and a Minneapolis resident, she has spent most of her life around different bodies of water in the state. She wants to write a research paper about water pollution in Minnesota, but is having a difficult time figuring out what to focus on. She is concerned about copper nickel mining in northern watersheds, wild rice cultivation, protecting the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, global warming and lakes in Minnesota and walleye harvests on Mille Lacs. Natalie feels that all of these issues are related to each other, but is wondering if she will be able to tie it all together. Natalie has developed a set of research questions for her topic:

-

- How are Ojibwe people affected by water pollution in Minnesota?

- What can Ojibwe people in Minnesota do to protect water resources in Minnesota?

- How do tribal governments affect change at state legislatures, especially in relation to treaties and environmental protection of natural resources?

Natalie knows that she needs government information to fully understand her topic. She also needs to find academic books and scholarly journal articles because that is required by her professor. She is interested in tribal activism and wants to find a way to highlight some of the important work of protestors and activists in her community.

Selecting Search Tools

Part of planning to conduct research is determining which search tools will be the best ones to use. This applies whether you are doing scholarly research or trying to answer a question in your everyday life, such as what would be the best place to go on vacation. “Search tools” might be a bit misleading, since a person might be the source of information you need.

Students often automatically search Google first, regardless of what they are looking for. Choosing the wrong search tool may waste your time and provide mediocre information, whereas other tools might provide spot-on information and quickly, too. In some cases, a carefully constructed search on Google, particularly using the advanced search option, will provide the necessary information, but other times it will not. This is true of all tools: make an informed choice about which ones to use for a specific need.

So, how do you identify the best search tools?

For academic research, talking with a librarian or professor is a great start. They can direct you to specialized tools that provide access to what you need. This chapter will cover generic search strategies and techniques that work in many search tools; however, a librarian can show you specialized techniques in different search tools to focus your search and retrieve the most relevant results.

If neither your professor nor a librarian is available when you need help, check your school’s library website to see what guidance is provided. There will often be research guides or subject guides to assist researchers. There should also be an A-Z list of the databases the library subscribes to, including important information about the subjects and formats these databases cover. Take advantage of the expertise of librarians by using such guides. Novice researchers do not usually look for this type of help, and, as a consequence, often waste time.

The Marietta College Library website (https://library.marietta.edu), has subject guides, course guides and access to over 200 research databases on a huge variety of research topics. The reference librarians are happy to show you how to effectively and productively search any of these tools.

When you are looking for non-academic materials, consider who cares about this type of information. Who works with it? Who produces it or help guides for it? Some sources are really obvious, and you are already using them—for example, if you need information about the weather in Marietta three days from now, you might check Weather.com instead of going to a library (in person or online), and you wouldn’t need to do database search. For other information you need, think the same way. Are you looking for anecdotal information on old railroads? Find out if there is an organization of railroad buffs. Librarians can point you to tools like these to help you find information, even if it isn’t for an academic paper or assignment.

What to Search

Database Research at your Academic Library

Databases are research interfaces that libraries either lease or develop for various physical and digital collections. In the day-to-day manner of speaking, when someone says “go search in a database” they mean go to a search interface for a particular collection of resources.

A Side Note about Library Catalogs and Discovery Interfaces

A library catalog is a database that contains bibliographic records of all of the items physically located in a library as well as select digital collections. Some academic libraries place every digital collection they subscribe to in their library catalog search, others make selections based on their campus community. The library catalog does not search the full text of an item, rather it searches the bibliographic record or description of an item. Many academic libraries place their library catalog in a discovery interface or search. These search interfaces might have branding like Onesearch or they might just look like a Google search box located on the library’s homepage. Discovery interfaces blend full text searching with bibliographic record searching, so some collections just have bibliographic records (like the circulating books) and other collections have full text availability (like a collection of scholarly journals). Discovery interfaces can be a great place to conduct research because they combine so many different formats and collections into one search. They can also be aggravating for expert researchers who know how to use the sophisticated features of databases for particular collections.

Searching Databases

Databases have interfaces that help researchers conduct simple searches and advanced searches. Advanced searching allows you to refine your search query and prompts you for ways to do this. Consider the basic Google.com search box. It is minimalistic, but that minimalism is deceptive. It gives the impression that searching is easy and encourages you to just enter your topic, without much thought, to get results. You certainly get many results. But are they good results? Simple search boxes sometimes do researchers a disfavor.

Advanced search screens show you the options available to you to refine your search, which should get you manageable numbers of relevant items. Many databases and web search engines include advanced search screens. Advanced search screens will vary from collection to collection, but they often let you refine your search in these ways:

- Implied Boolean operators (for example, the “all the words” option is the same as using the Boolean operator and)

- Limiters for date, domain (.edu, for example), type of resource (scholarly journal articles, e-books, patents), language, full text availability

- Field (a field is a standard element, such as title of publication, an author’s name or a subject heading)

- Phrase (rather than entering quotation marks around multiple words)

In most library databases, the search results page will have facets that allow you to apply advanced search refinements to your initial simple search. Commons sorts include: by date, alphabetical by author, and alphabetical by publication. Common refinements include: date ranges, full text availability, subjects or topics, publications, collections, format, and call number ranges. There is usually an option to add more terminology with Boolean operators.

Going back to the real-life scenario, if Natalie enters the simple search terms water and Minnesota into her library catalog, the results page will include suggestions for subject refinements including: environmental policy, causes and theories of causation, and conservationists. Natalie can click on any of these suggested refinements to add this subject to her initial simple search and get a set of more focused results.

Metadata

A bibliographic record is a descriptive record created by a cataloger or other metadata expert that describes an item in a collection. The description of items is called metadata, and this metadata is usually divided out into fields like: author, title, publication date and subject. Some important descriptive metadata you find in bibliographic records are: title, author, date of publication, table of contents, abstract or summary and subject/topical headings. A bibliographic record is made up of fields populated by metadata created by professionals. Subject heading searching can be a powerful way to find items in these sorts of collections. Also, starting with simple keyword searches is advisable, then you can apply refinements once you get to the search results page.

Controlled Vocabulary

If you search by subject in a library catalog you can take advantage of the controlled vocabulary created by the Library of Congress. Controlled vocabulary consists of terms or phrases that have been selected to describe a concept. For example, the Library of Congress has selected the phrase Environmental Law to represent laws and regulations governing the environment. So, if you are looking for books about American laws that impact our environment, you could enter the term Environmental Law into the subject search. Controlled vocabulary is important because it helps pull together all of the items about one topic. In this example, you would not have to conduct individual searches for environmental law, then environmental regulation, then environmental legal framework; you could just search once for Environmental Law and retrieve all the items about the laws and regulations governing the environment. Subject headings are particularly useful when you are researching something new to you or if English is not your first language. You can use this suggested terminology from databases to generate better searches and learn more about how others discuss your research topic. Once you start conducting subject searches, you will have access to the same refinements as a keyword search in your search results.

OhioLINK

In the scenario, Natalie performs a simple keyword search in the library catalog: water and minnesota. She finds several good resources on her topic and has her pick of books, e-books and streaming films. While the films look entertaining, Natalie decides to check out two print books for her research project. After writing down the call numbers, Natalie tries a different keyword search: Ojibwe and activism and Minnesota. This search brings up zero items in her library catalog, but she notices that she can expand her search to other academic libraries in Ohio. After she expands the search, she sees some interesting results including more books, a radio show recording, and some government documents. The government document records link to free reports on the Department of Natural Resources website. The books and recording are available as OhioLINK requests. After consulting with a librarian, Natalie learns that she can request the books from another library and have them delivered to her campus within a few days. She decides to order these books because they are at the heart of her research interests.

Full Text

Databases sometimes contain the full text of reference articles, scholarly journal articles, magazine articles, newspaper articles and e-books. Full text searching of resources lets researchers create searches that query the full text of resources in the database. Full text availability means that researchers have instant access to the resources of the database, no need to walk to a shelf at the library or make an OhioLINK request. When a database does not have full text searching, you are searching bibliographic records or descriptions of the various resources.

How to Search

Determining Search Concepts and Keywords

Keyword searching is our typical approach to using search boxes. You start by coming up with logical keywords or phrases and then put this terminology into a search box. You let the computer find these terms in bibliographic records or the full text of items, and then these items populate a search result.

When deciding what terms to use in a search, break down your topic into its main concepts. Don’t enter an entire sentence, or a full question. Different databases and search engines process such queries in different ways, but many look for the entire phrase you enter as a complete unit, rather than the component words. While some will focus on just the important words, the results are often still unsatisfactory. The best thing to do is to use the key concepts involved with your topic. In addition, think of synonyms or related terms for each concept. If you do this, you will have more flexibility when searching in case your first search term doesn’t produce any or enough results.

This may sound strange, since if you are looking for information using a Web search engine, you almost always get too many results. Databases, however, contain fewer items, and having alternative search terms may lead you to useful sources. Even in a search engine like Google, having terms you can combine thoughtfully will yield better results.

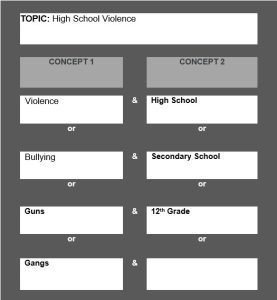

The following worksheet is an example of a process you can use to come up with search terms. It illustrates how you might think about the topic of violence in high schools. Notice that this exact phrase is not what will be used for the search. Rather, it is a starting point for identifying the terms that will eventually be used. You can find a blank copy of the worksheet at the end of this chapter for your use.

Boolean logic is a better way to construct searches. This is the form of mathematics that governs the behavior of search boxes. Boolean logic or search logic helps clarify what you mean when you search more than one term in a search box.

Before we get into search logic, it is helpful to start with terminology, the words you use to describe your research topic. In the scenario above, Natalie has well developed thinking on her research topic, so she can easily generate a list of important keywords and phrases that describe the information she is seeking in databases:

- “water pollution”

- Minnesota

- “Fond du Lac Band of Ojibwe”

- water

- “copper nickel mining”

- “northern watershed”

- “wild rice cultivation”

- “Boundary Waters Canoe Area”

- “global warming”

- lakes

- “walleye harvest”

- “Mille Lacs”

- “tribal government”

- “state legislature”

- treaties

- “environmental protection”

- “nature resource”

- activism

This list is not exhaustive, but it is starting to get at the main ideas of Natalie’s research topic. Some of this terminology singularly describes a concept, like: water, lakes, and activism. Some of this terminology requires more than one word to describe a concept, like: Boundary Waters Canoe Area, copper nickel mining and global warming.

In the world of search, any time you have more than one word in a search box, you should have search logic to clarify what you mean to the computer. Quotation marks tell a search box that you have a phrase, or a set of words that belong together in a specific order. You can see all the phrases in Natalie’s list have quotation marks. Phrase is the first type of search logic you are going to learn in this chapter.

Logical Operators

Once you have the concepts and terminology you want to search, you need to think about how you will enter them into the search box. Any time you have more than one word in a search box, you should clarify what you mean with Boolean search logic, expressed as logical operators. Sometimes using quotation marks and creating phrases is enough, often we have to go even further. There are several logical operators that work across databases: AND, OR, NOT, Truncation, Wildcard and Nesting. We’ll explore each of these operators in depth.

Boolean Operators: AND – OR – NOT

AND, OR and NOT are the most commonly used logical operators. They search concepts in three different ways. They do not have to be capitalized in a search box, they are capitalized here only for clarity.

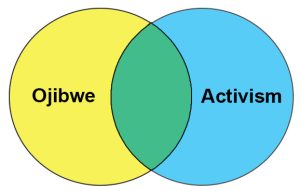

AND links concepts that are very different from one another. Natalie’s search of the library catalog is a good example: Ojibwe AND activism.

These concepts do not make up a phrase and you would not want a search to link these concepts together as a phrase. Using the AND operator, we make sure that the database knows to find items with both concepts in the bibliographic record or full text of a potential item. We can visualize this; imagine two circles that encompass all the items in a collection for each concept, the only items from these circles you will see in your search result are found in the intersection where the circles overlap (green area).

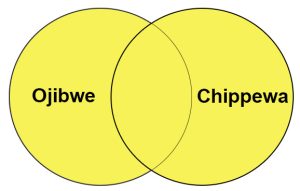

You can think of OR as an “either or” search. OR searches concepts that have similar meanings. Ojibwe is one name for the group of people that Natalie is part of, but this group has other names that get applied to them like Chippewa. If Natalie wanted to make sure she found all the items in a database about her people, she might need to type both of these terms into the search. OR would be a logical way to way to accomplish the ask: Ojibwe OR Chippewa. We can visualize this search; imagine two circles that encompass all the items in a collection for each concept, with the OR operator you will see every item in these circles show up in a search result.

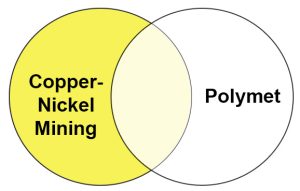

NOT is a filter, you use this operator to take a concept out of your search result. Let us imagine that Natalie has been looking into newspaper articles about copper nickel mining in Minnesota. She might find that a recent event, like the proposed opening of a new copper nickel mine in Hoyt Lakes Minnesota by the PolyMet mining company is over represented in her search results. To filter this out, she might try using the NOT operator like this: copper nickel mining NOT PolyMet. We can visualize this search, imagine two circles that encompass all the items in a collection for each concept, the only items from these two circles you will see in your search result are found in the first before you have overlap from the second.

Truncation and Wildcard

Truncation and wildcard are logical operators that help you find multiple variant forms of a word. The most common reason for needing variant forms of word is when you want the singular and plural version of a concept. Another reason you may need variant forms is that you have a root concept that gets expressed with slightly different endings or changes to letters in the middle. You use truncation when you need multiple letters to be different in the variant forms of a word. You use wildcard when you only need one letter to be different. In order to use truncation or wildcard, you need a root word to get started. The following sets of terms have a root word that we can truncate or wildcard.

-

- teen* = teen, teens, teenager

- wom?n = woman, woman, womin, womyn (these last two variants of woman are sometimes used in feminist literature)

- entrepreneur* = entrepreneur, entrepreneurship

- govern* = govern, governing, governor, governance, government

- cat? = cat, cats

- g??se = goose, geese

In sets of terms above, three stand out as straight forward truncations with a root word: teen*, entrepreneur* and govern*. You might also think cat, as in the feline animal that many of us have as pets, is another straightforward truncation. That would not work because cat* is a root word for lots of other words:

cat* = cat, cats, cathode, catastrophe, catapult, caterpillar, and so forth…

You might have noticed that wildcard operators can work in the middle of words, wom?n and g??se are good examples of this. Goose might behave a little strangely in a search. As stated g??se could also bring up the term guise, which is not at all related to goose and geese. In most databases, you can have up to three wildcard operators in a row.

Truncation and wildcard are powerful logical operators, but you should test them for weirdness. The way you test any logical operator is to try the search without the operator and then with the operator.

Nesting

Nesting is a way to prioritize the search when you are using multiple Boolean operators.

Every time you create a search with AND, OR or NOT, you are creating a search statement. If you have more than one search statement in a search box, each statement is read and executed from left to right. Without parentheses, this left to right execution can get confusing. Since Natalie has such a nice list of search terminology, we can take her words and combine them into Boolean searches with nesting.

- “Boundary Waters Canoe Area” AND (PolyMet OR “copper nickel mining”)

- (Ojibwe OR Chippewa OR Anishinaabe) AND (activism OR conservationism OR environmentalism) AND (Minnesota OR Wisconsin)

- water AND pollution AND Minnesota

- (Ojibwe OR Chippewa OR Anishinaabe) AND water

- pollution AND (water OR watershed? OR lake? or river?) NOT “storm water”

- “wild rice cultivation” AND “copper nickel mining”

- “global warming” AND (water OR watershed? OR lake? or river?)

- “copper nickel mining” AND (water OR watershed? OR lake? or river?) AND pollution

- (“walleye harvest” OR spearfishing) AND “Mille Lacs”

- (“water right?” OR “land use right?”) AND (“tribal government” OR “Fond du Lac”)

- (activis? OR conservationis? OR environmentalis?) AND water AND Minnesota

- “copper nickel mining” AND leach* NOT PolyMet

As you look over the list, you might see some patterns:

- OR search statements are typically placed in parentheses

- NOT search statements are typically placed at the end of a search string

- AND search statements can be placed everywhere

We can look at a nested statement to see how the parenthesis keep search statements behaving properly. Let’s look at this complex search string:

(Ojibwe OR Chippewa OR Anishinaabe)

AND (activis? OR conservationis? OR environmentalis?)

AND (Minnesota OR Wisconsin)

The parentheses force all the synonyms or words with similar meaning together. These OR searches become comprehensive search statements that get combined in many different ways. You basically get items with one word from

search statement 1, one word from search

statement 2 and 1 word from search statement 3.

Another example is this search string:

pollution

AND (water OR watershed? OR lake? or river?)

NOT stormwater

In this example, the parenthesis pulls all the synonyms or words with similar meaning together. The order of the search statements gets read left to rights, so pollution AND (water OR watershed? OR lake? or river?) are searched and combined as:

- pollution + water

- pollution + watershed?

- pollution + lake?

- pollution + river?

Finally, any item with the term stormwater is filtered out of the search result. Filtering out articles about stormwater should get rid of articles that talk about urban and suburban stormwater runoff problems, which Natalie may see as environmental water problems outside the influence of tribes in Minnesota.

In general, nesting can be a power logical operator when we use multiple Boolean operators in a search string. When organizing search statements:

- place AND and OR search statements before NOT search statements,

- place all OR statements in parentheses, to keep synonyms or like terminology together,

- read your search statements left to right and see if things make sense.

Putting It All Together

Databases are the primary way researchers access information in an academic library. It is important to understand the features of advanced search interfaces, to help construct advanced searches or refine simple searches within these environments. It is also important to create searches that computers understand, with correct logical operators and relevant terminology to your research topic. Generating a list of relevant terminology for your topic often means you need to do some preliminary research or have some personal experience with the topic you select, both of which helped Natalie create searches and find relevant resources. It is always advisable to do topic development before diving deep into research.

Learning Activities & Resources

Search Terms Worksheet