1 IDENTIFY

Understanding Your Information Need

In this chapter, you will learn about the first of seven pillars of information literacy. While the pillars are normally presented in a certain order, it is important to remember that they are not intended to be a step-by-step guide or followed in a strict order. In most research projects, you will find that you move back and forth between the different pillars as you discover more information and come up with more questions about your topic. In this chapter you will learn how to identify your information need so that you can begin your research.

The PIO 101 learning outcome that aligns with IDENTIFY is:

Students will be able to pose appropriate questions that will help

them and others develop deeper understanding of course content.

In this chapter:

- IDENTIFY: Understanding and Skills

- Understanding Context of an Information Need

- Defining Information Needs

- Make a Chart to Take Stock of What You already Know

- Make a KWHL Chart to Keep Track of What You Know and Learn

- Conduct a Preliminary Investigation

- Creating Research Questions and Thesis Statements

- A Wider View

- Learning Activites & Resources

IDENTIFY: Understanding and Skills

A person proficient in the IDENTIFY pillar is expected to be able to identify a personal need for information.

They understand:

- new information and data is constantly being produced and that there is always more to learn,

- being information literate involves developing a learning habit so new information is being actively sought all the time,

- ideas and opportunities are created by investigating/seeking information,

- the scale of the world of published and unpublished information and data.

They are able to:

- Identify a lack of knowledge in a subject area,

- Identify a search topic/question and define it using simple terminology,

- Articulate current knowledge on a topic,

- Recognize a need for information and data to achieve a specific end and define limits to the information need,

- Use background information to underpin the search,

- Take personal responsibility for an information search,

- Manage time effectively to complete a search.

Real-life Scenario

Hunter is a gamer and spends most of his free time playing Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Games (MMORPGs). When his Information Studies professor assigned a paper about the impact of the Internet on American Society, Hunter thought it was going to be an easy A, because he could write about gaming. Unfortunately, the paper has not been going well. Hunter is only coming up with the negative impacts of gaming for his paper. He knows that MMORPGs are fun to play and that all his best friends are gamers. However, most of the other people in his life tell him that MMORPGs are a massive waste of time, highly addictive and definitely nerdy. Hunter does not have strong arguments for why MOORPGs are good for American Society and he is quickly losing interest in writing the paper.

Understanding Context of an Information Need

Information need describes the desire to locate and obtain information that is relevant in relation to successfully satisfying a given task.

That task may be an assignment to write a paper or to prepare for a discussion or presentation in class. The task may be for personal development, such as knowing how to participate in a job interview or deciding what career you may want to pursue. Or, it may be a driving interest to study a topic that you’ve been wanting to learn more about and not related to a school assignment at all.

Regardless of the reason you have a need for information, one of the first things to do when beginning a research project is to acknowledge that you likely do not already know enough to proceed. School and professional assignments, and even personal improvement, are best accomplished by researching to find relevant information that is complete, non-biased, and current. By assuming we already know enough, we usually end up wasting valuable time working with incomplete, biased or outdated information that will be inadequate or unacceptable for best results in completing the task.

When you develop a topic, it is important that you explore the existing information landscape to find out what is already out there. You need to think broadly about the information environment in which you are operating. For instance, any topic you need information about is constantly evolving as new information is discovered and added. Trained experts, informed amateurs, and opinionated laypeople are publishing in traditional and emerging formats; there is always something new to find out. Part of becoming information literate is developing habits of mind and of practice that enable you to continually seek new information and to adapt your understanding of topics according to what you find. While you are busy searching for information on your current topic, be sure to keep your mind open to new topics or arguments you have not considered. Often the information you find for your initial need will change the way you think about or frame a topic.

Undergraduate students are often assigned papers and projects that require informational research. This type of research differs from scientific research in a few important ways.

- Informational research involves interpretation and discovery of information that is already produced.

- Scientific research involves experimental design and produces something tangible that can be reproduced.

- Another important feature of informational research is that it can be reexamined and reinterpreted at a later date because our information landscape is always changing.

- Informational research can be used to create an argument, analyze different facets of a topic, or introduce a body of literature.

When you understand the information environment where your information needs are situated, you can begin to define the topic more clearly and understand where your research fits in with related work that precedes it.

Defining Information Needs

In the real-life scenario, Hunter was abruptly confronted by his lack of knowledge when he realized that he had mostly negative things to write about MMORPGs. At this point, he has to decide whether to do some research or abandon his topic. While the path of least resistance is appealing, doing research into something important to you can be rewarding. If Hunter finds positive arguments for MMORPGs, he can use them in his paper and in real life.

Your own lack of knowledge may become apparent in other ways. When reading an article or textbook, you may notice that something the author refers to is completely new to you. You might realize while out walking that you can’t identify any of the trees around your house. You may be assigned a topic you have never heard of.

For example: You can’t explain why your coat repels water. You know that it’s plastic, and that it’s designed to repel water, but can’t explain why this happens. You need to find out what kind of plastic the coat is made of, the chemistry of that plastic, and the physics that makes the water run off instead of soaking through. Keep in mind that the terminology in your first explanation will get more sophisticated once you do some research.

LEARNINGACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 1A can help you identify what you don’t know about a topic, and what you need to know.

All of us lack knowledge in countless areas and this is not a bad thing. Once we acknowledge that we don’t know something, it opens up the possibility that we can find out all sorts of interesting new things.

Taking your lack of knowledge and turning it into a topic or research question starts with being able to identify the knowledge you lack. We rarely start a research project from absolute zero. Most of the time you have heard something about the topic, even if it is just a brief reference in a lecture or reading. Taking stock of what you already know can help you to identify assumptions you are making based on incomplete or biased information. If you think you know something, make sure you find at least a couple of reliable sources to confirm that knowledge before taking it for granted. Use the following exercise to learn what needs to be supported with background research.

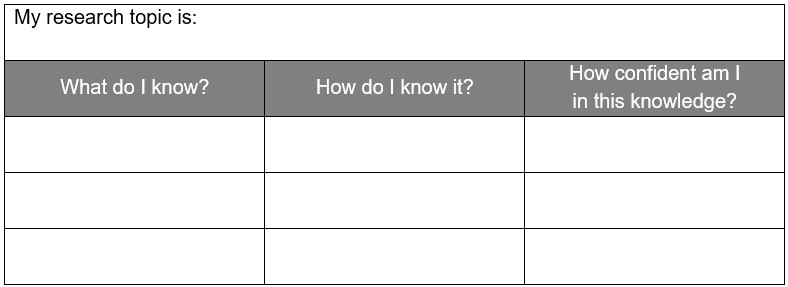

Make a Chart to Take Stock of What You Already Know

As discussed above, part of identifying your own information need is giving yourself credit for what you already know about your topic. Before you begin research take time to write down a list of what you already know about the topic.

An easy way to do so is to construct a chart similar to the one below, adding a many lines as needed.

- Write your research topic at the top.

- In the first column, list what you know about your topic.

- In the second column, briefly explain how you know this (from the professor, read it in the textbook, saw it on a blog, etc.).

- In the last column, rate your confidence in that knowledge. Are you 100% sure of this bit of knowledge, or did you just hear it somewhere and assume it was right?

Now that you have written down everything you know about the topic, step back and look at the whole chart. You may be surprised at how little or how much you know, either way you will be more aware of your own background knowledge on the topic. This exercise should give you a starting point and may help you identify specific gaps in your knowledge.

After you have clearly stated what you know, it should be easier to state what you don’t know. Keep in mind that you are not attempting to state everything you don’t know. You are letting your current information need guide this exercise. This is where you define the limits of what you are searching for. These limits enable you to meet both size requirements and time deadlines for a research project. If you have a clear goal in mind, you can keep yourself on track as you proceed with your research.

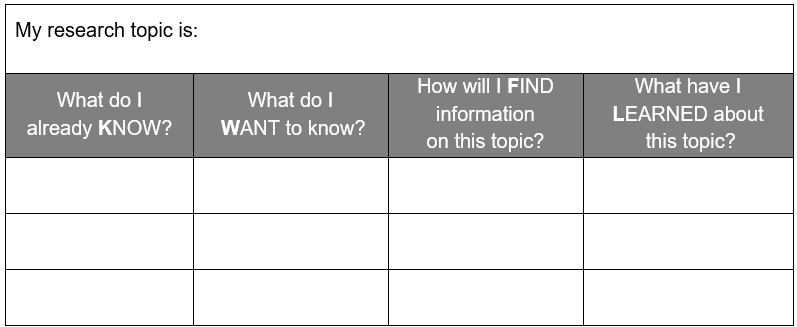

Make a KWFL Chart to Keep Track of What You Know and Learn

A useful way to keep your research on track is to construct a chart similar to the one below so you can write down what you already know and what you want to know. Later you will use this chart to include how you will find information you need and what you have learned about the topic.

Start by making four columns.

- In the left KNOW column list the things from your earlier chart that you already know about the topic.

- In the WANT column, write down what you want to know. For example, if you listed that you already know something about the topic but your were only 60% confident in your knowledge being accurate, write down that you want to check that piece of information from another source. If you don’t know anything about some facet of the topic, write down what you would like to know about it. You can add as many lines to the chart as needed.

- When you have everything written down, you can look at how you FIND each bit of information you have noted in the WANT column. (refer to the PLAN chapter)

- When you have completed the planned research, list your new knowledge in the LEARNED column.

It can be useful to revisit this chart as you work on your research project to see how far you’ve progressed or to double check that you haven’t forgotten an area of weakness.

Conduct a Preliminary Investigation

Defining a research question can be difficult. Your initial questions may be too broad or too narrow. You may not be familiar with specialized terminology used in the field you are researching. You may not know if your question is worth investigating at all. These problems can often be solved by a preliminary investigation of existing published information on the topic. In academic research, it is important to look for experts who have laid the groundwork for you to build upon. On a more practical note, gathering background information can provide you with commonly used terminology and arguments. Having the right background knowledge can help you create thoughtful research questions and construct more precise searches.

Creating Research Questions and Thesis Statements

Now that you have identified your knowledge gaps, conducted a preliminary investigation on the topic and set limits on your research based on your current information need. You are ready to write out your research question or thesis statement. Research questions and thesis statements can be understood as two sides of the same coin. You can start with a research question and restate it as a thesis statement, or vice versa. The characteristics of a good research question can be used to create a good thesis statement. A good research question has several characteristics.

-

- The answer to a research question should not be immediately obvious.

A good research question encourages exploration. It should force you to seek out new and varied information, not just one fact or figure. The research question should not be answered with a simple yes or no. It should require that you analyze several sources of information to get a complete answer.

-

- A research question should help you feel focused.

A good research question helps you focus on a specific context. This context could be a specific time period, human population, geographic area or set of circumstances. You have a clear sense of who or what you are researching. It does not require you seek out information indefinitely.

-

- A research question should address an issue or controversy, or seek to solve a problem.

Whenever possible, you should articulate the controversy or issues concerning your research topic. A typical research assignment seeks to answer a question, find a solution or convince your audience of a stance. If you need a strong set of arguments or solutions, then you should ask questions that address the issue or controversy explicitly.

-

- A research question is hopeful.

Sometimes a controversy or issue seems overwhelming. You may feel like the answer is impractical or improbable for humans to execute. Try not to despair, and do not frame your research questions in exaggerated or apocalyptic language. Also, avoid creating open ended questions that reflect your feelings about human frailty. Accept that humans are not perfect and find the workable solutions.

-

- An informational research question is not theoretical or revisionist.

It is fun to think about alternative realities, theoretical possibilities or revised histories. If you are assigned a research project, you will find the whole endeavor more productive if you stick to what is known about the world. When scholars, academics, researchers or scientists explore the unknown they use disciplinary research methods to make new discoveries. If you go far enough in your academic journey, you will learn how to conduct original research or set up scientific experiments.

-

- Informational research requires a body of information to explore.

Do not worry about perfection. You should revise your research question or thesis statement several times during the course of a research project. As you become more and more knowledgeable about the topic, you will be able to state your ideas more clearly and precisely, until they almost perfectly reflect the information you have found.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 1B can help you to get a better grasp of exactly what you are trying to find out, and to identify some initial search terms to get you started.

A Wider View

While IDENTIFY is presented as the first step in a research process, you may find yourself circling back to topic development many times during a research process. It is impossible to keep up with an evolving information landscape and we often start out with incorrect assumptions or outdated information. Other chapters in this book deal with evaluating, managing and presenting information during a research process. You may revisit your initial ideas about your topic in response to what you’re doing with what that information later on.

Students often think that their lived experience is not relevant to or researched in scholarly circles. Hunter was carrying baggage about Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Games when he started writing about it for a class. A little preliminary research and topic development will go a long way to assuage your fears about finding scholarly sources of information. Professors, researchers, scientists and practitioners study all sorts of real world phenomena and draw interesting conclusions about what they observe.

Learning Activities & Resources

Exercise 1A: Identifying What You Don’t Know

- Wherever you are, look around you. Find one thing in your immediate field of view that you can’t explain.

- What is it that you don’t understand about that thing?

- What is it that you need to find out so that you can understand it?

- How can you express what you need to find out?

Exercise 1B: Research Question/Thesis Statement/Search Terms

Since this chapter is all about determining and expressing your information need, let’s follow up on thinking about that with a practical exercise. Follow these steps:

- Whatever project you are currently working on, there should be some question you are trying to answer. Write your current version of that question here.

QUESTION: - Now write your proposed answer to your question. This may be the first draft of your thesis statement which you will attempt to support with your research, or in some cases, the first draft of a hypothesis that you will go on to test experimentally. It doesn’t have to be perfect at this point, but based on your current understanding of your topic and what you expect or hope to find is the answer to the question you asked.

DRAFT THESIS: - Look at your question and your thesis/hypothesis, and make a list of the terms common to both lists (excluding “the,” “and,” “a,” etc.). These common terms are likely the important concepts that you will need to research to support your thesis/hypothesis. They may be the most useful search terms overall or they may only be a starting point.

COMMON TERMS:

If none of the terms from your question and thesis/hypothesis lists overlap at all, you might want to take a closer look and see if your thesis/hypothesis really answers your research question. If not, you may have arrived at your first opportunity for revision. Does your question really ask what you’re trying to find out? Does your proposed answer really answer that question? You may find that you need to change one or both, or to add something to one or both to really get at what you’re interested in. This is part of the process, and you will likely discover that as you gather more information about your topic, you will find other ways that you want to change your question or thesis to align with the facts, even if they are different from what you hoped.