4 GATHER

Finding What You Need

There are many types of information sources. Knowing the differences in sources helps to make research less confusing. Additionally, understanding the information included in citations and works cited can help identify additional sources to help in gathering information.

The PIO 101 learning outcome that aligns with GATHER is:

Students will recognize primary, secondary, and tertiary sources;

peer-reviewed sources.

In this chapter:

- GATHER: Understanding and Skills

- The Information Cycle and The Internet

- Primary, Secondary , and Tertiary Sources

- Newspaper Articles

- Scholarly Journal Articles

- Books

- Citations, Works Cited, and References

- MLA Style Basics

- MLA Citation and Works Cited

- Citation and Works Cited Examples

- Printed Books

- Academic Journal Articles

- Webpages

- Websites

- Conclusion

- Learning Activities & Resources

Real-life Scenario

Harry Dosital is feeling overwhelmed by one of his class assignments. Harry would have been happy if the assignment was to write a traditional research paper but his professor has asked the class to solve a real life problem. The professor has asked the class to imagine a small city undergoing a natural disaster such as a flood or a tornado. Each group in the class is required to plan a hypothetical information command center for this city. The professor explains that the government needs to obtain accurate, up-to-date information on the scope of the damage and injuries sustained due to the disaster. This information is vital for the city to be able to provide adequate emergency and medical assistance to its citizens. Harry can see that this is an important function for any city in the midst of a crisis but he is not sure about where to get reliable information to help him construct a plan for the city.

Harry and his classmates do some brainstorming and decide to approach this assignment as if they were actually producing a research paper. Their first step will be to research recent disasters. They reason that this will provide some information about the way some cities have gathered information during disasters. If an information gathering strategy worked for other cities, it will work for their hypothetical city. There certainly have been a lot of natural disasters recently, so it shouldn’t be too hard to find some information. Super Storm Sandy in 2012 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 are two events that i come to mind. The group starts to research Super Storm Sandy with Google and Wikipedia.

Harry and his classmates are engaging in the GATHER pillar of the Seven Pillars of Information Literacy model. Just as municipalities needed to gather reliable information in order to provide vital services to their citizens, Harry and his group members need to gather information that will help them complete this assignment.

GATHER: Understanding and Skills

These information needs are components of the GATHER pillar, which states that the information literate individual understands:

- How information and data are organized,

- How libraries provide access to resources,

- The different elements of a citation,

- The use of abstracts,

- The difference between free and paid resources.

They are able to

- Use a range of retrieval tools and resources effectively,

- Access full text information, both print and digital,

- Find personal, expert help.

The Information Cycle and the Internet

Traditionally, information has been organized in different formats, usually as a result of the time it took to gather and publish the information. For example, the purpose of news reporting is to inform the public about the basic facts of an event. This information needs to be disseminated quickly, so it is published daily in print, online, on broadcast television, and radio media. More in-depth treatment of information takes longer to research, write, and publish and traditionally was published in scholarly journals and books.

Today, information is still published in traditional formats as well as on the Internet. These information sources can include electronic journals, books, news websites, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and location postings. The coexistence of all of these information formats is messy and chaotic. The process for finding relevant information is not always clear.

One way to make some sense out of the current information universe is to thoroughly understand traditional information formats. We can then understand the concepts inherent in the information formats found online. There are some direct correlations such as books and journal articles, but there are also some newer formats like tweets that didn’t exist twenty years ago.

Let’s look at the news industry. Many traditional newspapers are shutting down and those that remain are retrenching. While there are many reasons for this, one of the major trends has been the rise of the Internet. In 2021 more than 86 per cent of the US population read the news online (Shearer).

Indeed, online news sites provide a different and, some might argue, a more relevant experience for the reader. They offer video and sound, up-to-the-minute updates on breaking news, and the ability to interact with the content by posting comments. Another important feature of online news is that search engines can deliver content from the site in response to a query. In other words, readers don’t have to visit a site such as the New York Times to read its content.

This has both positive and negative consequences. The positive consequence is that readers can quickly and conveniently obtain information from a variety of sources on a topic or event. The negative consequence is that it is more difficult to evaluate the credibility of the sources. The EVALUATE chapter in this book provides some good strategies for evaluating information sources.

For Harry and his group, all of this means they will have to research many kinds of information resources to create an effective information command center. The group finds there are several types of sources that present information from different perspectives.

Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources

When searching for information on a topic, it is important to understand the value of primary, secondary, and tertiary sources. Primary sources allow researchers to get as close as possible to original ideas, events, and empirical research as possible, while Secondary sources analyze, review, or summarize information in primary resources or other secondary resources. Tertiary sources provide overviews of topics by synthesizing information gathered from other resources.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Examples of primary sources include autobiographies, personal correspondence (e.g., diary entries, letters), government documents, works of art and literature, statistics and data, and newspaper articles written by reporters close to the source. Today, even some social media posts are considered primary sources, because they are firsthand accounts of information.

A member of Harry’s group recalled that he had cousins in New York City who experienced Super Storm Sandy firsthand. He offered to interview his cousins about their experiences during the storm. This type of first-person information is known as a primary information or source.

Primary sources can be found in a variety of locations and formats. There are many online sites that have created digitized collections of copies of diaries and letters from historical events. It is important to remember that primary sources are not limited to a single format. You may find them in books, journals, newspapers, email, websites, and artwork. You can quiz yourself on primary sources in a learning activity at the end of this chapter.

KEY TAKEAWAY

A primary source is a firsthand or eyewitness account of information by an individual who experienced the event or period being considered or a source containing raw original information that is not interpreted, condensed, or evaluated.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Examples of secondary sources include histories, biographies, interpretation of statistics and data, literary criticism, textbooks, and anything written after an historical event or analyzing something that already happened (e.g., examining a work of art from 100 years ago).

KEY TAKEAWAY

A secondary source is a second-hand account by people not experiencing the event or period, containing interpretation, analysis, and/or criticism of the information.

TERTIARY SOURCES

Tertiary sources can be a good place to look up facts or get a general overview of a subject, but they rarely contain original material. Examples include dictionaries and encyclopedias, almanacs, guidebooks, directories, indexes, bibliographies, catalogs, and search engines.

Depending on your research, you may need more primary or secondary sources. For example, if you wanted to trace the history of whale sightings off the coast of Alaska, you would probably need to find some historical documents that provide firsthand information on whale sightings from a few hundred years ago. However, if you wanted to look at how boating has changed whale migration patterns, you would probably rely on some secondary sources that interpret data and statistics.

KEY TAKEAWAY

A tertiary source presents summaries or condensed versions of materials, usually with references back to the primary and/or secondary sources.

Defining a source as primary, secondary, or tertiary can also depend on how you are using the material. For example, a magazine article may be either primary and secondary.

-

- A magazine article reporting on recent studies linking the reduction of energy consumption to the compact fluorescent light bulb would be a secondary source.

- A research article or study proving such a link would be a primary source.

- However, if you were studying how compact fluorescent light bulbs are presented in the popular media, the magazine article could be considered a primary source.

The distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources also can be confusing because different discipline areas may view documents differently and . For example, an indiviual document may be a primary source in one context and a secondary source in another. (Primary)

In the Humanities and Social Sciences

In the humanities and social sciences, primary sources are the direct evidence or first-hand accounts of events without secondary analysis or interpretation. In contrast, secondary sources analyze or interpret historical events or creative works.

PRIMARY SOURCES |

SECONDARY SOSURCES

|

TERTIARY SOURCE |

| A primary source is an original document containing firsthand information about a topic. Different fields of study may use different types of primary sources, such as diaries, interviews, letters, original works of art, photographs, speeches, or works of literature. | A secondary source contains commentary on or discussion about a primary source. The most important feature of secondary sources is that they offer an interpretation of information gathered from primary sources: biographies, dissertations, indexes, abstracts, journals, articles, or monographs. | A tertiary source presents summaries or condensed versions of materials, usually with references back to the primary and/or secondary sources. They can be a good place to look up facts or get a general overview of a subject, but they rarely contain original material: dictionaries, ncyclopedias, or handbooks. |

EXAMPLES

| Subject | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

| Art | Painting | Critical review of the painting |

Encyclopedia article on the artist |

| History | Civil War diary | Book on a Civil War battle |

List of battle sites |

| Literature | Novel or poem | Essay about themes in the work |

Biography of the author |

In the Sciences

In the sciences, primary sources are documents that provide full descriptions of the original research. For example, a primary source would be a journal article where scientists describe their research on the genetics of tobacco plants. A secondary source would be an article commenting on, or analyzing the scientists’ research on tobacco.

| PRIMARY | SECONDARY | TERTIARY |

| These are where the results of original esearch are usually first published in the sciences. This makes them the best source of information on cutting edge topics. This includes conference proceedings, interviews, journals, lab notebooks, patents, preprints, technical reports, or theses and dissertations. | These tend to summarize the existing state of knowledge in a field at the time of publication. Secondary sources are good to find comparisons of different ideas and theories and to see how they may have changed over time: books, reviews, textbooks, or treatises. | These types of sources present condensed material, generally with references back to the primary and/or secondary literature. They can be a good place to look up data or to get an overview of a subject, but they rarely contain original material. Tertiary sources include compilations, dictionaries, encyclopedias, handbooks, or tables |

EXAMPLES

| Subject | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary |

| Agriculture | Conference paper on tobacco genetics | Review article on the current state of tobacco research | Encyclopedia article on tobacco |

| Chemistry | Chemical patent | Book on chemical reactions | Table of related reactions |

| Physics | Einstein’s diary | Biography on Einstein | Dictionary of relativity |

Newspaper Articles

One of the members of Harry’s group suggested they should consult a newspaper to see what role the newspaper played to help the city understand the destruction caused by the storm. The group chose the New York Times. The New York Times can be accessed online through Factiva, one of the library’s databases. Few articles from the day of the storm were found. The group found that more useful information was published in the New York Times in the days after the storm. Looking for information that was published days, weeks, or months after the storm took place was a good strategy.

Other newspapers can be accessed online or at the library through databases such as Factiva and a few others.

Scholarly Journal Articles

The results of the research that Harry and his group have done are useful, but Harry is concerned that there might be too much focus on Super Storm Sandy. He wants to find more information on crisis and disaster management in general. Harry thinks that there might be general standards or practices that should be incorporated into his group’s plan. Journal articles and books might provide this information.

Harry starts his search for journal articles by using a multidisciplinary database because he is not sure which specific disciplines will cover the information he seeks. He constructs and executes a search query and finds that the abstracts included in the results help him choose several peer-reviewed, or scholarly, articles to read.

Scholarly journal articles usually include an abstract at the beginning of the article. An abstract summarizes the contents of the article. In an abstract, key points as well as conclusions are briefly described. Abstracts are often included in the database record. Researchers find this information helpful when deciding whether or not to retrieve the whole article.

Most of the articles that Harry chooses are available in PDF format from the database, but there are a few articles that look very relevant that don’t have links to a PDF. Harry really wants to read these articles so he decides to try to find out if there is another way to obtain the full text. He consults a librarian who instructs him to look for the title of the journal (not the article) in the online catalog. The catalog record will provide information on whether the journal is available online from another database or if it is available in print in the library. It will also provide information about whether the journal is peer-reviewed, which is a consideration when evaluating sources. (see the EVALUATE chapter for more information)

Libraries have entered into agreements to share their journal and book collections with other libraries. If you are affiliated with a library as a student, staff, or faculty member, you have access to many other libraries’ resources, through a service called interlibrary loan. Do not pay the large sums required to purchase access to articles unless you do not have another way to obtain the material, and you are unable to find a substitute resource that provides the information you need.

Books

Next, Harry’s group looks for books on the topic. They search the library’s online catalog using search terms that were successful in their database searches. They find some great titles and head to the library stacks to retrieve them.

Most academic libraries use the Library of Congress classification system to organize their books and other resources. The Library of Congress classification systems divides a library’s collection into 21 classes or categories. A specific letter of the alphabet is assigned to each class. More detailed divisions are accomplished with two and three letter combinations. Bookshelves in most academic libraries are marked with a Library of Congress letter-number combination to correspond to the Library of Congress letter-number combination on the spines of library materials. This is often referred to as a call number and it is noted in the catalog record of every physical item on the library shelves.

Harry uses the call numbers to locate some books that he found in the catalog. He is happily surprised to find that there are also some really useful books sitting on the shelf right next to the books he previously identified. This is a handy way to find additional information resources on a topic. It is more efficient to first search the online catalog to locate relevant resources and then search the shelves.

Library of Congress Classification

- A General Works — includes encyclopedias, almanacs, indexes

- B-BJ Philosophy, Psychology

- BL-BX Religion

- C History — includes archaeology, genealogy, biography

- D History — general and eastern hemisphere

- E-F History — America(western hemisphere)

- G Geography, Maps, Anthropology, Recreation

- H Social Science

- J Political Science

- K Law (general)

- KD Law of the United Kingdom and Ireland

- KE Law of Canada

- KF Law of the United States

- L Education

- M Music

- N Fine Arts — includes architecture, sculpture, painting, drawing

- P-PA General Philosophy and Linguistics, Classical Languages, and Literature

- PB-PH Modern European Languages

- PG Russian Literature

- PJ-PM Languages and Literature of Asia, Africa, Oceania, American Indian

Languages, Artificial Languages - PN-PZ General Literature, English and American Literature, Fiction in English, Juvenile Literature

- PQ French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese Literature

- PT German, Dutch, and Scandinavian Literature

- Q Science — includes physical and biological sciences, math, computers

- R Medicine — includes health and human sexuality

- S Agriculture

- T Technology — includes engineering, auto mechanics, photography, home economics

- U Military Science

- V Naval Science

- Z Bibliography, Library Science

Citations, Works Cited, and References

As Harry’s group starts to read and digest all of the information they have gathered, they notice that many articles and books contain references to other articles and books. Even Wikipedia entries contain references. These consist of citations to resources that authors have quoted or paraphrased in their work or have used to research for their publications. Some of these citations look like they would provide great information. But the group is confused. They don’t know if the citation is to a book or an article or something else.

Understanding the basic parts of citations and works cited / references is important during the GATHER pillar, as you search the work of others to help identify and locate their sources. Knowledge about citations will also be important in the EVALUATE, MANAGE, and PRESENT pillars as you record your research sources and present them in your writing and presentations.

Citations and references can be confusing. In-text citations appear in the body of the text and their purpose is to point to additional information at the end of the text.

Works cited/references are added toward the end of the main text as a list. In MLA style this list is called a Works Cited list; in APA style it is called References. The purpose of a works cited/references lists is to supply additional information about sources cited in the work.

The structure and content for citations is different than the structure and content for works cited/references and to make things more confusing, there are many different citation formatting styles that have slightly different rules about the structure of the citation or reference. Plus, there are not many hard and fast rules about when to use a particular style.

PIO 101 and PIO 102 classes will use MLA style for class assignments.

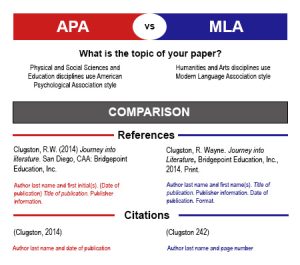

Your professors in other classes may indicate which citation style you should use. If not, the general rule of thumb is:

- Physical and Social Sciences and Education disciplines use APA (American Psychological Association) citation style

- Humanities and Arts disciplines use MLA (Modern Language Association) or the Chicago style.

It is helpful to know that all citation styles have some things in common, most notably that they contain certain information about a source.

Common elements of a work cited/reference, in all styles, include:

- The author(s) name(s)

- The date of dissemination (printing, posting to a website, presentation given, etc.)

- The title of the work (title of a paper or presentation, webpage title, etc.)

- The title of the distribution channel, such as the title of the academic journal, website, podcast, video, or other way in which the work was distributed

- Often the company or organization that published or disseminated the source is named, as well

A citation (in the body of the academic paper or other source) is a shortened version of the reference and “refers” to the longer reference information that’s listed above. A citation includes:

- The author(s) name(s)

- OR, If there is no author’s name, a shortened version of the title of the work

- In some styles, the date of dissemination (publication or posting of the work)

- In some styles, the page number where the information is found

This image compares an MLA reference to an APA reference, looking at the same source formatted in both styles.

Why even bother?

Two easy answers: credibility and honesty.

Credibility. When you acknowledge others’ work, you build your own credibility as an informed person. By correctly citing someone else’s work, you strengthen your own work by building your ideas, conclusions, and findings on the work of other scholars. When you review the citations of information you find in other people’s work during your research, you also expect them to be credible and use this as one test of whether the information you have found is reliable—more about that in the EVALUATE chapter.

Academic Honesty. Using the work or idea of another person without acknowledging the work belongs to that person—and thereby representing it as your own work–is plagiarism. Plagiarism is a form of theft, since it involves taking the words, ideas, or artwork of others and passing them off as your own. As such, it’s academically dishonest and can have serious consequences for students, as well as later, when you are a career professional.

Citations and works cited/references are tools you use to give credit and to avoid dishonesty. They can be helpful in your research, as well, because they can lead you to additional information about your topic that may not have appeared in your initial searches.

When are citations not needed?

Information that is “common knowledge” does not require citation. Common knowledge is information that is accepted and known widely. Generally, if you can find information undocumented in at least five credible sources it would be considered common knowledge. For example, “writing is difficult,” is considered common knowledge in the field of composition studies because at least five credible sources can back the claim up.

Use common sense and ethics when deciding if you need to document sources. You do not need to give sources for familiar proverbs, well-known quotations, or common knowledge. (For example, it is expected that U.S. citizens know that George Washington was the first President.)

Where to find help with citations and works cited/references

Next, we will review formatting basics for MLA style, but there are several sources of help if you need detailed information about how to format a citation or reference in any of these styles. One helpful website, Purdue OWL, is available online at https://owl.purdue.edu. There are several other authoritative sites available, and you can also obtain guidance on formatting citations at the Marietta College Writing Center or help from the reference librarians at Legacy Library, who can guide you to the most recent copy of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers, the latest Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, for APA citations, or the current Chicago Manual of Style.

MLA Style Basics

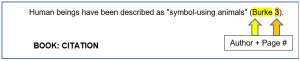

Because your PIO 101 and 102 classes, as well as WRIT 101 and 102, will expect you to use MLA, this section will focus on common uses of MLA style. In MLA Style, referring to the works of others in your text is done using parenthetical citations. This method involves providing relevant source information in parentheses whenever a sentence uses a quotation or paraphrase. Any source information that you provide in-text must correspond to the source information on the Works Cited page.

The most common formats that you will encounter are books, journal articles, and websites, so an example of each will be shown below as a reference and an in-text citation.

MLA Citations & Works Cited

CITATION FORMAT:

For printed material, like books or journal articles, the author’s last name and the page number(s) from which the quotation or paraphrase is taken must appear in the citation, in parentheses before the end of sentence punctuation. A complete reference for the source should appear on your Works Cited page.

Romantic poetry is characterized by the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” (Wordsworth 263).

If the author’s name appears in the sentence itself, it does not need to be included in parentheses, but the page number(s) should always appear in the parentheses, not in the text of your sentence.

Wordsworth extensively explored the role of emotion in the creative process (263).

For other types of sources, the citation may include other information. For example, a webpage source would not have page numbers, and the author’s name may not be known. In that case you should include the first item that appears in the Works Cited entry that corresponds to the citation (e.g. author name, article name, website name, film name).

Below are examples of citations for some different types of sources you may encounter. When you find a source that is not included here, refer to the sources listed above for help.

WORKS CITED FORMAT:

If readers want more information about a source cited in the text, as above, they can turn to the Works Cited page, where further information about the source is included. What information is included and the format depends on the type of source.

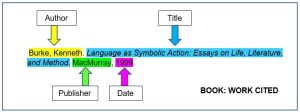

For a book, a reference would include:

Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication Date.

Wordsworth, William. Lyrical Ballads. Oxford UP, 1967.

*Note: the City of Publication should be included before the Publisher only if the book was published before 1900, if the publisher has offices in more than one country, or if the publisher is unknown in North America.

MLA Citation and Works Cited Examples

In this section examples of the parenthetical citation and the corresponding work cited are included for some commonly used sources.

Printed Books

When citing information from a printed book include the author and the page number where the information was found. In the corresponding work cited, include the author’s name, the title of the book in italics, the name of the publisher (which can be found in the front pages of the book) and the date it was published.

In-text, parenthetical citation

Corresponding Works Cited reference

Variations

- When a book has two authors, order the authors in the same way they are presented in the book. (Example: Gillespie, Paula, and Neal Lerner.)

- If there are three or more authors, list only the first author followed by the phrase et al. (Example: Wysocki, Anne Frances, et al. )

If the book is electronic, indicate that the book is an e-book by putting the term “e-book” before the publisher, separated by a comma. Example:

Silva, Paul J. How to Write a Lot: A Practical Guide to Productive Academic Writing. E-book, American Psychological Association, 2007.

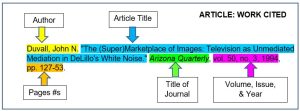

Academic Journal Articles

Cite the author and page number as you would for a book. Then, in the work cited, put the title of the article followed by the title of the journal in italics. Include the volume number (“vol.”) and issue number (“no.”) when possible, separated by commas. Finally, add the year and page numbers on which the articles appears.

In-text, parenthetical citation

Corresponding Work Cited Reference

Variations:

- If the journal you are citing appears in an online format, indicate the URL or other location information (DOI) AND the date you accessed the online version. Example:

Dolby, Nadine. “Research in Youth Culture and Policy: Current Conditions and Future Directions.” Social Work and Society: The International Online-Only Journal, vol. 6, no. 2, 2008, www.socwork.net/sws/article/view/60/362. Accessed 20 May 2009.

*If it is available both online and in print, include page range.

- If the article is from an online database include the source (e.g. LexisNexis, ProQuest, JSTOR, ScienceDirect) Example:

Langhamer, Claire. “Love and Courtship in Mid-Twentieth-Century England.” Historical Journal, vol. 50, no. 1, 2007, pp. 173-96. ProQuest, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X06005966. Accessed 27 May 2009.

Webpages

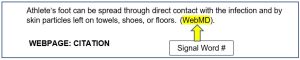

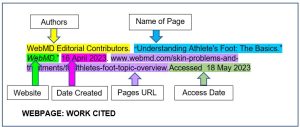

For an individual page or a website, list the author or alias if known, followed by an indication of the specific page or article being referenced. Usually, the title of the page or article appears in a header at the top of the page. In the citation you can use a “signal word” that identifies the corresponding work cited in a shorter form.

In-text, parenthetical citation

Corresponding Work Cited Reference

Variations:

- If the author isn’t known, begin with the name of the page.

- If a DOI is available, precede it with “https://doi.org/”, otherwise use a URL (without the https://) or permalink.

- The title of the webpage or article title is laced in quotation marks and the name of the website is in italics.

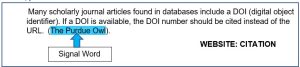

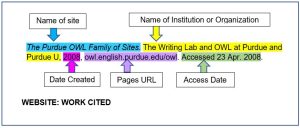

Website

When citing an entire website, include the website name and a compiler or author name if available.

In-text, parenthetical citation

Corresponding Work Cited Reference

Variations:

- If the compiler isn’t known, begin with the name of the site.

- Online newspapers and magazines sometimes include a “permalink,” which is a shortened, stable version of a URL. Look for a “share” or “cite this” button to see if a source includes a permalink. If you can find a permalink, use that instead of a URL.

- The title of the webpage or article title is placed in quotation marks and the name of the website in italics.

CONCLUSION

Harry and his classmates have spent time gathering information to help them create a realistic and accurate crisis command center. They used online newspapers and online journal articles. They even gathered some very useful hard copy books. During this process, the students learned about different ways that information is organized, including the Library of Congress classification system. Harry was amazed at the wealth of quality information he was able to gather. It took him a while and the process was more complicated than just searching the web, but Harry now feels more confident about acing the assignment. He also feels that he learned more than how to set up a command center. He learned how to engage in academic research!

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES

Quiz: Primary Sources

1, Where would you find a speech by Franklin Delano Roosevelt in which he said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”?

A. Web site of Presidential Speeches

B. Newspaper article dated Oct. 29, 1941

C. A print publication titled “Vital Speeches of the Day,” which has been published since 1934

D. All of the above

2, Which of the following sources is the most likely to contain an interview with Steven Spielberg about his film “Lincoln,” produced in 2012?

A, Article from a news magazine dated November 23, 2012

B. A blog written by a fan of Steven Spielberg

C. IMDb –A large online database of movie and television information

D. All of the above

3. Which source would have the original copy of a diary written a woman who lived in Tennessee during the Civil War?

A. The Library of Congress American Memory Project web site

B. The Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

C. Local public library’s collection

D. All of the above

4. Which of the following is a primary source?

A. A review of the film “Lincoln” by Steven Spielberg

B. A nonfiction book about the Civil War titled The Fall of the House of Dixie : The Civil War and the Social Revolution that transformed the South

C. The Facebook privacy policy

D. A reporter’s article about an event that happened yesterday, written from information gathered from bystanders