5 EVALUATE

Assessing Your Research Process and Findings

Most students struggle to find time to do everything. Researching an academic paper could be the kind of time-consuming process that pushes them over the edge. Professors have high standards for the kinds of resources they want students to use and they expect students to cite information and use information in the right context.

We all do research, but how do you decide who to trust or what information to accept or leave behind? Context, authorship, and evidence help you determine authority, trust, and reliability. This chapter covers two important, but sometimes time consuming, steps in the research process: evaluation and analysis.Here are some ways to ensure that you are getting the best information possible when researching. Before we get into some way to do that, watch the video Inform Your Thinking: Episode 2 – Who Do You Trust and Why?

OKStateLibrary (2016) Inform Your Thinking: Episode 2

Evaluating and analyzing resources matter when you need information to make important decisions or evidence-based conclusions. These skills help you judge the reliability of resources and put those resources into action. While these skills are emphasized in academic research, they are equally useful to students making important personal decisions.

There are shortcuts to evaluation and analysis, which can save you time and effort. One big time saver is to use the academic library. The resources you find in databases and on shelves have been placed there by a librarian, so these resources have already been evaluated to a certain extent. Using academic resources can also save time when you start reading and analyzing the text. Traditional academic publishing required standard formatting that has carried through to the digital age. You can use this formatting to your advantage.

This chapter will explain the concepts behind evaluating and analyzing resources. It will also outline processes and guiding questions you can use to do evaluation or analysis effectively.

The PIO 101 learning outcome that aligns with EVALUATE is:

Students will be able to evaluate sources for credibility, relevance, and accuracy.

In this chapter:

- EVALUATE: Understanding and Skills

- Distinguishing Between Information Resources

- Social Media

- News Articles

- Magazine Articles

- Scholarly Articles

- Books

- STEP 1: Choosing Materials

- Quzlity

- Acuracy

- Relevance

- Bias

- Reputation

- Credibility

- Evaluating your source’s source

- STEP 2: Identifying Key Points and Arguments

- Table of Contents

- Reading a scholarly article

- STEP 3: Analyzing Information Resources

- Knowing When to Stop

- Applying Theory to Practice

- Conclusion

- Learning Activities & Resources

EVALUATE: Understanding and Skills

The EVALUATE pillar states that individuals are able to review the research process and compare and evaluate information and data. It encompasses important knowledge and abilities.

The information literate person in the EVALUATE pillar understands:

- The information and data landscape of their learning/research context,

- Issues of quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility relating to information and data sources,

- How information is evaluated and published, to help inform their personal evaluation process,

- The importance of consistency in data collection,

- The importance of citation in their learning/research context.

They are able to

- Distinguish between different information resources and the information they provide,

- Choose suitable material on their search topic, using appropriate criteria,

- Assess the quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation and credibility of the information resources found,

- Assess the credibility of the data gathered,

- Read critically, identifying key points and arguments,

- Relate the information found to the original search strategy,

- Critically appraise and evaluate their own findings and those of others,

- Know when to stop.

Real-life Scenario

Emilio has resolved to eat healthier and work out more. He just finished his first year of college and is not ready for the summer soccer season. As a nursing student, Emilio took a required nutrition course and he thinks he has the basics down. However, he feels his course work did not fully address diets for athletes with performance goals. In addition, he wants to develop a workout routine that he can maintain during the school year.

While writing a paper for the required nutrition course, Emilio learned about the health and science databases in his college library. He knows there are a lot of fad diets and “get pumped quickly” workouts on the web and he does not want to waste his time on gimmicks. He has been collecting interesting nutrition articles shared through his social media networks and he is following several fitness instructors on Instagram. Emilio is a bit intimidated, but he is going to take his research to the next level. He is going to see if the articles he found through social media are using evidence-based practice. He is going to start building his nutrition and workout plan today.

Distinguishing Between Information Resources

Information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations when it comes to evaluation. Consider the following formats.

Social Media

Social media is prominent in the landscape of information gathering. Facebook updates, Instagram posts, tweets, wikis, Tik Toks, YouTube, and blogs have made information creators of us all. These platforms have a strong influence on the way we gather and disseminate information. Social media is often the first place we learn about current events or discover new items of interest. Anyone can create or contribute to social media, and there are no gatekeepers to fact check for accuracy or censor slanderous or hateful speech.

Information Scientists might use social media for the aggregate data that is collected from users to gain insights, but this requires special training. Most other academics use social media as primary source accounts of the human experience around historic events or social phenomena. You might look for the social media posts of the politically powerful, intellectually important or socially influential to gain their insights. Eyewitness accounts and reactions may also be important sources of information for context.

News Articles

These days, social media platforms are the first place many people get information about a big news story. News media often post to social media as they learn new facts and insights. Longer form news articles and reports are generated quickly as the story progresses. News articles are written by journalists who report on an event they have witnessed firsthand, or after they make contact with those more directly involved. Journalists focus on information that is of immediate interest to the public and they write so that a general audience can understand the content.

In research, news articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event.

Magazine Articles

While news articles and social media tend to concentrate on what happened, how it happened, who it happened to, and where it happened, magazine articles tend to explore why something happened, usually with the benefit of a little hindsight. Writers of magazine articles also fall into the journalist category and rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Fact-checking in magazine articles tends to be more accurate because magazines publish less frequently than news media, so they have more time to get the facts right. Depending on the focus of the magazine, articles may cover current events or just items of general interest to the intended audience. The language may be more emotional or dramatic than the factual tone of news articles, but the articles are written at a similar reading level to appeal to the widest audience possible. Magazines can be a more accessible resource to explore why something happened.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts in an academic field of study. They typically describe formal research studies or experiments conducted to provide new insight on a topic rather than reporting current events or items of general interest. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. Peer reviewed articles undergo a review process carried out by professional researchers, academics and industry experts. This group checks the accuracy of the information presented in a scholarly article and the validity of the research methods used to conduct the research behind the findings.

Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is meant for an expert audience. They provide the framework for researchers and scholars to build new original research projects. Scholarly articles carry a lot of weight in academic research and professors often require their use in undergraduate assignments.

Books

Books have been a staple of academic research since Gutenberg invented the printing press. A research topic can be covered more deeply in a book than most other information sources. Also, the conventional wisdom for books is that anyone can write one, but only the best ones get published. This is becoming less true as books are published in a wider variety of formats, which is something to be aware of when using a book for research purposes. Research in the humanities, which include academic disciplines such as literature and history, is primarily published in this format.

STEP 1: Choosing Materials

When choosing a source for your research, what criteria do you usually use? Gauging whether the source relates to your topic at all is probably one. How high up it appears on the results list when you search may be another. Beyond that, you may base your decision at least partly on how easy it is to access.

While these may be important criteria, there are other criteria you should keep in mind when deciding if a source will be useful to your research.

Quality

Clues to a source’s level of quality are closely related to thinking about how the source was produced, including what format it was published in and whether it is likely to have gone through a formal editing process prior to publication.

Scholarly journals and books are traditionally considered to be higher quality information sources because they have gone through a more thorough editing process that ensures the quality of their content. Generally, you also pay more to access these sources or may have to rely on a library or university to pay for access for you.

Accuracy

A source is accurate if the information it contains is correct. Sometimes it’s easy to tell when a piece of information is simply wrong, especially if you have some prior knowledge of the subject. But if you’re less familiar with the subject, inaccuracies can be harder to detect, especially when they come in subtler forms such as exaggerations or inconsistencies.

To determine whether a source is accurate, you need to look more deeply at the content of the source, including where the information in the source comes from and what evidence the author uses to support their views and conclusions. It also helps to compare your source against another source.

Relevance

Does the source relate to your topic and, if it does, how closely does it relate? Some sources may be an exact match; for others, you may need to consider a particular angle or context before you can tell whether the source applies to your topic. When searching for relevant sources, you should keep an open mind—but not too open. Don’t pick something that’s not really related just because it’s on the first page or two of results or because it sounds good.

You can assess the relevance of a source by comparing it against your research topic or research question. Keep in mind that the source may not need to match on all points, but it should match on enough points to be usable for your research beyond simply satisfying a requirement for an assignment.

Bias

An example of bias is when someone expresses a view that is one-sided without much consideration for information that might negate what they believe. Bias is most prevalent in sources that cover controversial issues where the author may attempt to persuade their readers to one side of the issue without giving fair consideration to the other side of things. If the research topic you are using has ever been the cause of heated debate, you will need to be especially watchful for any bias in the sources you find.

Bias can be difficult to detect, particularly when we are looking at persuasive sources that we want to agree with. If you want to believe something is true, chances are you’ll side with your own internal bias without consideration for whether a source exhibits bias. When deciding whether there is bias in a source, look for dramatic language and images, poorly supported evidence against an opposing viewpoint, or a strong leaning in one direction.

Reputation

What is the reputation of the author and the publication in which the source appears? Is the author a professor? A blogger? If the author is a professor, are they respected in their field or is their work heavily challenged?

Digging a little deeper to find out what you can about the reputation of both the author and the publication can go a long way toward deciding whether a source is valuable.

You can investigate the reputation of an author by looking at any biographical information that is available as part of the source. Looking to see what else the author has published and whether this information has positive reviews is also important in establishing whether the author has a good reputation. The reputation of a publication can also be investigated through reviews, word-of-mouth by professionals in the field, or online databases that keep track of statistics related to a journal’s credibility.

Credibility

Is the source believable or trustworthy based on the evidence such as information about the author, the reputation of the publication, how well “put together” the source is – these factors all contribute to whether a source has credibility. How likely would you be to use a source that was written by someone with no expertise on a topic or a source that appeared in a publication that was known for featuring low quality information? What if the source was riddled with spelling and formatting errors? Looking at sources like these should inspire more caution.

Objectively, credibility can be determined by taking into account all of the other criteria discussed for evaluating a source. Knowing that some types of sources, such as scholarly journals, are generally considered more credible than others, such as self-published websites, may also help. Subjectively, deciding whether a source is credible may come down to a gut feeling. If something about a source doesn’t sit well with you, you may decide to pass it over.

Evaluating your source’s sources

Evaluating the sources you use for quality, accuracy, relevance, bias, reputation, and credibility is a good first step, but have you ever thought about evaluating the sources used by your own sources? This takes extra time, but looking at the reference list, bibliography, or notes section of any source you use to gauge the quality of the research done by the author of that source can be an important extra step.

STEP 2: Identifying Key Points and Arguments

Evaluating information about the source from its title, author, and summary information is only the first step. The process continues when you begin to read the source in more detail and make decisions about how (or whether) you will ultimately use it for your own research.

Many academic sources of information are created with standard formatting guidelines that make it easier for users to browse and understand quickly. When you begin analyzing your resource, pay close attention to the following features of a book or article. Quickly scanning these parts of the resource can help you determine if the resource is worth pursuing further.

Introductions, Forwards, Prefaces, Abstracts

The purpose of the introduction to any piece that has one is to give information about what the reader can expect from the source as a whole. They hint at what the author is trying to accomplish with their book or article. Abstracts in particular will detail research methods used and ultimate conclusions in a scholarly article. Introductory sections can include information on why the topic was chosen, the author’s interest in the topic, why the topic is important, or the lens through which the topic will be explored. Knowing this information before diving in to the article or book will help you understand the author’s approach to the topic and how it might relate to the approach you are taking in your own research. These sections might also help you evaluate the author.

Table of Contents / Menu

Most of the time, if your source is a book or an entire website, it will be divided into sections that each cover a particular aspect of the overall topic. It may be necessary to read through all of these sections in order to get a “big picture” understanding of the information being discussed or it may be better to concentrate only on the areas that relate most closely to your own research. Looking over the table of contents or menu will help you decide whether you need the whole source or only pieces of it.

References, Bibliographies, Works Cited, Footnotes and Endnotes

If the resource you are using is research-based, it should list out the sources of information. Sources of information can be found within the work, these are typically footnotes, endnotes, in-text citations or references. Academic books and scholarly journal articles usually have bibliographies or works cited pages at the end of the work, where all the sources of information used in the work can be found. This large list of sources can give you a big picture view of the research the author engaged in. Some academic books list out the sources in bibliographies or works cited pages at the end of each chapter.

Newspaper and magazine articles typically mention their sources of information in the narrative of their work. That makes it a little more difficult to track down exact reports, studies or research referenced. If the newspaper or magazine article is web based, hyperlinking is a newer approach to creating in-text references for the readers to look into. If you really like what an author has to say in their book or article, the references can lead you to other relevant articles, books, reports or people to look into. This is called mining the bibliography.

Reading a scholarly article

Academic (and in particular, scientific) writing is not like other types of writing you may have encountered in the past. Academic writing tends to be information-dense, and therefore effective academic reading is hard work. This is due in part to the fact that when scholars write for an academic audience, they can assume a different level of preparation on the part of their readers than someone who is writing a book or article for more general consumption.

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

To help you identify key points and arguments in an academic paper, review the resource “How to Read a Paper”

STEP 3: Analyzing Information Resources

Once you have identified relevant articles, books, websites and sections of books, you need to do a more in-depth analysis of your resources. Analysis can help you find answers to your research questions, solutions to your problems, and logical arguments to organize your thoughts. This examination of specific resources is the most time-consuming part of your research process because it requires careful reading of your resources. Often this examination is done while you are developing your final research project. To do this effectively, you need to take time to read and examine resources.

Knowing When to Stop

For some researchers, the process of searching for and evaluating sources is a highly enjoyable, rewarding part of doing research. For others, it’s a necessary evil on the way to constructing their own ideas and sharing their own conclusions. Whichever end of the spectrum you most closely identify with, here are a few ideas about the ever-important skill of knowing when to stop.

- You’ve satisfied the requirements for the assignment and/or your curiosity on the topic.

- If you’re doing research as part of a course assignment, chances are you’ve been given a required number of sources. Novice researchers may find this number useful to understand how much research is considered appropriate for a particular topic. However, a common mistake is to focus more on the number of sources than on the quality of those sources. Meeting that magic number is great, but not if the sources used are low quality or otherwise inappropriate for the level of research being done.

- You have a deadline looming.

- Nothing better inspires forward motion in a research project than having to meet a deadline, whether it’s set by a professor, an advisor, a publisher, or yourself. Time management skills are especially useful, but since research is a cyclical process that sometimes circles back on itself when you discover new knowledge or change direction, planning things out in minute detail may not work. Leaving yourself enough time to follow the twists and turns of the research and writing process goes a long way toward getting your work in when it’s expected.

- You need to change your topic.

- You’ve been searching for information on your topic for a while now. Every search seems to come up empty or full of irrelevant information. You’ve brought your case to a research expert, like a librarian, who has given advice on how to adjust your search or how to find potential sources you may have previously dismissed. Still nothing. It could be that your topic is too specific or that it covers something that’s too new, like a current event that hasn’t made it far enough in the information cycle yet. Whatever the reason, if you’ve exhausted every available avenue and there truly is no information on your topic of interest, this may be a sign that you need to stop what you’re doing and change your topic. If you are working on an assignment for class, you should discuss a change of topic with your professor.

- You’re getting overwhelmed.

- The opposite of not finding enough information on your topic is finding too much. You want to collect it all, read through it all, and evaluate it all to make sure you have exactly what you need. But now you’re running out of room on your flash drive, your Dropbox account is getting full, and you don’t know how you’re going to sort through it all and look for more. The solution: stop looking. Go through what you have. If you find what you need in what you already have, great! If not, you can always keep looking. You don’t need to find everything in the first pass. There is plenty of opportunity to do more if more is needed!

Applying Theory to Practice

Evaluation is arriving at a conclusion of the quality of something (whatever research you’re using).

Analysis is the in-depth study of the material to better understand the information being presented. Evaluation is subjective; analysis is objective.

Now that you know more about the theory, it’s time to apply the theory.

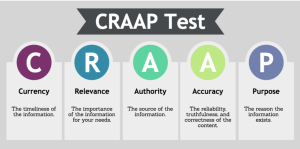

The following section will help you put source evaluation into perspective using something called the CRAAP Test. The CRAAP Test is a list of questions to help you evaluate the information you find. Not all criteria apply equally to all articles but will give you confidence that your sources meet the expectations of your assignment. (Evaluating)

The CRAAP test is a series of common evaluative elements you can use. The test was developed by librarians at California State University at Chico and it gives you a good, overall set of elements to look for when evaluating a resource. Let’s consider what each of these evaluative elements means.

CURRENCY: Assessing currency means understanding the importance of timely information

Certain topics require you to pay special attention to how current your resource is—because they are time sensitive, because they have evolved so much over the years, or because new research comes out on the topic so frequently.

-

-

-

-

- When was the information published or posted?

- Has the information been revised or updated?

- Does your topic require current information, or will older sources work as well?

- WEB SOURCE: Are the links functional?

-

-

-

RELEVANCE: The importance of the information for your specific needs.

Understanding what resources are most applicable to your subject and why they are applicable can help you focus and refine your thesis. Many topics are broad and searching for information on them produces a wide range of resources. Narrowing your topic and focusing on resources specific to your needs can help reduce the piles of information and help you focus in on what is truly important to read and reference.

-

-

-

-

- Does the information relate to your topic or answer your question?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Is the information at an appropriate level (i.e. not too elementary or advanced for your needs)?

- Have you looked at a variety of sources before determining if this is one you will use?

- Would you be comfortable citing this source in your research paper?

-

-

-

AUTHORITY: Authority is the source of the information—the author’s purpose and what their credentials and/or affiliations are.

Understanding more about your information’s source helps you determine when, how, and where to use that information. Is your author an expert on the subject? Do they have some personal stake in the argument they are making? What is the author or information producer’s background?

-

-

-

-

- Who is the author / publisher / source / sponsor?

- What are the author’s credentials or organizational affiliations?

- What qualifies the author to write about this topic?

- What affiliations does the author or organizational affiliate have? Could these affiliations affect their position?

- What organization or body published the information? Is it authoritative? Does it have an explicit position or bias?

- WEB SOURCE: Does the URL reveal anything about the author or source? examples: .com .edu .gov .org .net

-

-

-

ACCURACY: Accuracy is the reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content.

Determining where information comes from, if evidence supports the information, and if the information has been reviewed or refereed can help you decide how and whether to use a source.

-

-

-

-

- Where does the information come from?

- Is the information supported by evidence? Is the source well-documented? Does it include footnotes, citations or a bibliography?

- Can you verify any of the information from another source or from personal knowledge?

- Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

- Does the language or tone seem unbiased and free of emotion?

- Is the information written clearly and free of typographical and grammatical mistakes?

- Does the source look to be edited before publication?

- WEB SOURCE: Is the information crowd sourced or vulnerable to changes by other authors, i.e. Wikipedia or other public wiki?

-

-

-

PURPOSE: Purpose is the reason the information exists—determine if the information has clear intentions or purpose and if the information is fact, opinion, or propaganda.

-

-

-

-

- What is the author’s purpose? Is it to inform, teach, sell, persuade, or entertain?

- Do the authors / sponsors make their intentions or purpose clear?

- Is the information fact, opinion, or propaganda?

- Is the article presented from multiple points of view?

- Are there political, ideological, cultural, religious, institutional or personal biases?

- Is the information clearly supported by evidence?

-

-

-

LEARNING ACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

-

Exercises 5A-5E can help you practice using CRAAP.

-

CRAAP Test Evaluation Rubric: When you search for sources for a project, you’re going to find a lot of information…but is it credible and reliable? Use this guide to help you determine this for yourself.

Conclusion

Emilio has a clear goal for his research and a good understanding of the information environment he lives in. He is willing to accept that information from his personal social networks should be verified by academic experts. Emilio is capable of developing an excellent nutrition and workout plan. However, a lot depends on his willingness to engage in evaluating and analyzing his resources.

Learning Activities & Resources

Exercise 5A: Assess Currency

Imagine you are writing a paper for a Political Science class on Japan’s environmental policy since the Kyoto Treaty. Identify one resource that you would find helpful in your research, and one resource that you would find less helpful. Write one sentence explaining why you would or would not use each resource, paying special attention to the currency of each item.

Exercise 5B: Find Relevant Sources

You are researching a paper where you argue that vaccinations have no connection to autism. Which of these resources would you consider relevant? Why or why not?

Hviid, Anders, Michael Stellfield, Jan Wohlfart, and Mads Melbye. “Association Between Thimerosal-Containing Vaccine and Autism.” Journal of the American Medical Association 290, no. 13 (October 1, 2003): 1763–1766. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=197365

Chepkemoi Maina, Lillian, Simon Karanja, and Janeth Kombich. “Immunization Coverage and Its Determinants among Children Aged 12–23 Months in a Peri-Urban Area of Kenya.” Pan-African Medical Journal 14, no.3 (February 1, 2013). http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/14/3/full/

Exercise 5C: Identify Authoritative Sources

The following items are all related to a research paper on women in the workplace. Write two sentences for each resource explaining why the author or authors might or might not be considered authoritative in this field:

Carvajal, Doreen. “The Codes That Need to Be Broken.” New York Times, January 26, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/27/world/27iht-rules27.html?_r=0

Sheffield, Rachel. “Breadwinner Mothers: The Rest of the Story.” The Foundry Conservative Policy News Blog, June 3, 2013. http://blog.heritage.org/2013/06/03/breadwinner-mothers-the-rest-of-the-story

Baker, Katie J.M. “Your Guide to the Very Important Paycheck Fairness Act.” Jezebel (blog), January 31, 2013, http://jezebel.com/5980513/your-handy-guide-to-the-very-important-paycheck-fairness-act

Exercise 5D: Find Accurate Sources

Which of the following articles are peer reviewed? How do you know? How did you find out? Were you able to access the articles to examine them?

-

-

- Coleman, Isobel. “The Global Glass Ceiling.” Current 524 (2010): 3–6.

- Lang, Ilene H. “Have Women Shattered the Glass Ceiling?” Editorial, USA Today, April 14, 2010, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/opinion/forum/2010-04-15-column15_ST1_N.htm?csp=34

- Townsend, Bickley. “Breaking Through: The Glass Ceiling Revisited.” Equal Opportunities International 16, no. 5 (1997): 4–13.

-

Exercise 5E: Identify Information Purpose

Take a look at the following sources. Why do you think this information was created? Who is the creator?

-

-

- http://www.chevron.com/globalissues/climatechange/

- http://www.beefnutrition.org/

- Fahrenheit 911—Movie. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0361596/

- Lydall, Wendy. Raising a Vaccine Free Child. Inkwazi Press, 2009

- http://www.nwf.org/What-We-Do/Protect-Habitat/Gulf-Restoration/Oil-Spill/Effects-on-Wildlife.aspx

- http://zapatopi.net/treeoctopus/

- Owen, Mark and Kevin Maurer. No Easy Day: The Firsthand Account of the Mission That Killed Osama Bin Laden. New York: Penguin, 2012.

-

Find the following resources in the Supplementary Material chapter.

Find the following resources in the Supplementary Material chapter.

How to Read a Paper: A guide to reading academic papers.

What is a Scholarly Article? Ways to determine if your article is scholarly and/or peer reviewed.

CRAAP Test Evaluation Rubric: When you search for sources for a project, you’re going to find a lot of information…but is it credible and reliable? Use this guide to help you determine this for yourself. Give the source a score based on this point system. Is it credible and reliable or a bunch of …?