2 SCOPE

Knowing What is Available

In addition to knowing that you are missing essential information, another component of information literacy is understanding that the information you seek may be available in different formats such as books, journal articles, government documents, blog postings, and news items. Each format has a unique value and understanding those differences helps to guide your search.

The PIO 101 learning outcome that aligns with SCOPE is:

Students will be able to recognize types of sources (conference proceedings, newspaper articles, journal articles, books, anthologies, etc.) and be able to identify sources by category: primary, secondary, tertiary, and peer-reviewed sources.

(also see CH 4)

In this chapter:

- SCOPE: Understanding and Skills

- How is your Information Created?

- The Information Cycle

- Where Can You Find Information?

- Web Searches: Free Market Information and Filter Bubbles

- Access – is free really free?

- Filter bubbles – who determines what you find?

- Academic Libraries

- Reference Information

- Books

- Newspaper and Magazine Articles

- Scholarly Articles

- Government Information

- Library Catalogs

- Locating Resources in the Library

- Web Searches: Free Market Information and Filter Bubbles

- Where Can Your Find Help?

- How to Be a Strategic Researcher

- Learning Activities & Resources

SCOPE: Understanding and Skills

A person who is information literate in the SCOPE pillar is able to assess current knowledge and identify gaps. They understand:

- What types of information are available,

- The characteristics of the different types of information sources available and how the format of the source—such as digital or print– may affected them,

- How the publication process is related to how current a source is,

- Why individuals publish information,

- Issues of accessibility,

- What services are available to help and how to access those services.

They are able to:

- “Know what you don’t know” to identify any information gaps,

- Identify which types of information will best meet the specific need,

- Identify the available search tools, such as general and subject specific resources at different levels,

- Identify different formats in which information may be provided,

- Demonstrate the ability to use new tools as they become available.

Real-life Scenario

Mohamed is active in his Mosque and a student group for Muslims on campus. He was born into a Muslim family and lives in a community with Muslims from all over the Middle East and Africa. He is interested in how greater American society perceives the Muslim faith and to what extent it welcomes faithful Muslims into everyday life. He knows that there are kind and welcoming non-Muslims in his community and on campus, but he also sees tensions and conflicts between people of different faiths or backgrounds. Mohamed wants to put together a research paper about this topic for his Writing course, but is nervous about the directive from his professor to use academic books and scholarly journals about this topic.

How Is Your Information Created?

Information is literally everywhere. We have the ability to create and share information in a split-second and send it out to the world. That information can be shaped and packaged in different ways based on how the information was created. What can the package, or format, tell us about how the information was created in the first place? Before reading more about how where to find information, watch this 3:46 minute video about how information is created.

OKStateLibrary (2016) Inform Your Thinking: Episode 5

The Information Lifecycle

The information lifecycle is the progression of media coverage of a particular newsworthy event. Understanding the information cycle will help you to better know what information is available on your topic and better evaluate information sources covering that topic.

Most professors do not want a simple account of the world, they want a deeper examination. When college professors ask students to use academic books and scholarly journal articles, they are asking students to seek out information that examines, analyzes, synthesizes, scrutinizes and frames issues using scholarly perspectives, theories and research methods. To help us better understand how information is created and disseminated, the graphic below represents a common process of information dissemination, known as The Information Cycle. (Illinois)

The graphic demonstrates the Information Cycle process during a period of time.

- When an event happens, we usually hear about it quickly from social networks and news sources first. Information on the day of the event:

- Includes the who, what, why, and where of the event are reported.

- Is quick, but not detailed; it is regularly updated.

- Is authored by journalists, bloggers, social media participants.

- Is intended for general audiences.

- Within a few days after the initial news of an event, more details and analysis of the event is communicated, often by newspapers.

- Explanations and timelines of the event begin to appear.

- More factual information may include statistics, quotes, photographs, and editorial coverage.

- Authors are journalists.

- Is intended for general audiences.

- Six Months or More After an Event, the event has been studied in more depth and articles, often peer reviewed, are disseminated through academic, scholarly journals. These articles are:

- Focused, detailed analysis and theoretical, empirical research,

- Peer-reviewed, ensuring high credibility and accuracy,

- Authored by scholars, researchers, and professionals,

- Intended for an audience of scholars, researchers, and university students.

- A Year to Years After an Event, in-depth coverage and analysis is published in books and/or reports..

BOOKS

- In-depth coverage ranging from scholarly in-depth analysis to popular books

- Authors range from scholars to professionals to journalists

- Include reference books which provide factual information, overviews, and summaries

GOVERNMENT REPORTS

- Reports from federal, state, and local governments

- Authors include governmental panels, organizations, and committees

- Often focused on public policy, legislation, and statistical analysis

LEARNINGACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Exercise 2A can help you think about how the Information Cycle can guide you in beginning your information search for different topics.

Referring back to the scenario at the opening of the chapter, as Mohamed seeks out scholarly information for his college research paper, he should think about how the specific topic he is interested in exploring fits into larger social problems, scientific theories, legislative solutions or academic disciplines.

Mohamed might explore what scholars have to say about the assimilation of Muslim immigrants into American society, or how Muslims and Christians coexist in American society over time or how recent events in the Middle East have affected Muslims in America. Simple web searches do not typically lead to information that addresses this degree of complexity. There are scholarly journal articles, extensive government reports, in depth journalistic pieces and documentaries on the web; however, you have to know where to look.

Where Can You Find Information?

Thinking about where Mohamed may find the information sources needed for his research paper, consider the following possibilities.

Web Searches: Free Market Information and Filter Bubbles

Because The Information Cycle begins with an event that is disseminated across social networks or news sources, it is tempting to think this is where you should start a research project. Many of us are introduced to new events, ideas, organizations, people and places in our social networks or trusted news sources. We might even have an important news article, blog post, personal experience or podcast that inspires the research project we are interested in exploring for a class. Taking your inspiration from real life events or personal experiences is a great idea, but doing research in your preferred digital ecosystem is not advisable.

There are two problems with conducting research through our social networks and in web browsers:

- most of us lack access to high quality information, and

- when we interact with the internet most of us are subject to algorithmic intervention—where a computer follows step-by-step instructions to perform a task (an algorithm) that makes inferences about data that includes things such as identity, demographic attributes, preferences, past behavior, and likely future behavior to automate decisions about what you are looking for and determine what search results may be provided.

Let’s look at each of theses issues more closely.

Access – is free really free?

When you are conducting research for a college level course, most professors require the use of peer reviewed journals or scholarly publications. These high quality information resources are not typically given away for free. If you pay for access to every article or book you want to read for a research paper, you will quickly find research to be an expensive endeavor. Two examples:

Google Scholar: Many scholarly articles can be found in a Google Scholar (or other preferred browser) search; however, when you go to the website to access the article you are given a free abstract of the article but then may be asked to pay for the full text. But, if you are on Marietta College’s campus you can access the scholarly articles via Google Scholar.

Scholarly books: The same can be true of scholarly books; you can get a free preview but have to pay for a full text view of the book online. Scholarly information is valuable and can command high prices in the free market. But, if you are using the Marietta College library databases, such as OhioLINK Electronic Book Center, you have free access to many scholarly ebooks, as well.

The Legacy Library is a resource that provides you with access to a wealth of sources and services. Your tuition helps pay for this information and it has been vetted by librarians, so you know it will be appropriate for college level research.

Filter Bubbles – who determines what you find?

The more subtle problem with research across social networks and through web browsers is algorithmic intervention. Companies that provide web-based services, like social media platforms or web browsers, have powerful incentives to keep you engaged with their platform or application: advertising revenue and personal data collection. Facebook, Twitter, Google and other web-based service providers keep your business and increase your participation on their platforms by presenting you with content that entertains or resonates with you. They employ sophisticated algorithms to make sure you enjoy connecting with people, events, ideas, organizations and advertising on their platforms. These companies also collect as much personal information about you as they can to tailor your experience and perhaps sell this data to other companies.

If you use a web-based platform enough you will find yourself in a Filter Bubble, a place that presents you with agreeable and entertaining information at the expense of challenging or disagreeable information. The vast majority of free web-based services or applications rely on personal data collection and advertising revenue to get and keep your business. Conducting research in this kind of environment will limit your ability to find multiple perspectives, especially perspectives that differ from your own view of the world.

Academic Libraries

Academic libraries are an important place for students to conduct research. They are not interested in collecting personal data from students or optimizing search so that students only find agreeable or entertaining content. Academic library collections are developed with students and faculty in mind. They are tailored to the academic programs, assignments and research needs of the campus. Students who become familiar with the organization and collections of an academic library will save themselves time and effort when conducting research for college classes. Academic libraries primarily collect scholarly information in a variety of formats; however you will also find information from journalists and government officials. In this way, academic libraries mirror the classroom. Professors are primarily concerned with scholarship and academic ways of thinking about the world, but they are keenly aware of how this relates to greater society.

Mohamed knows he needs to use academic books and scholarly journal articles for his paper, but it is important to understand how these required resources relate to other formats in an academic library collection. Scholarly information is published in a variety of formats, each with its own special considerations in regard to conducting research. The formats described below can be found on physical shelves and in digital searches of databases or catalogs.

Librarians are available in Legacy Library to help you navigate the library and advise you on your information search.

LEARNINGACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Resources: Take a video tour of Legacy Library.

You might use the following formats as you conduct research at your academic library.

Reference Information

In an academic library, reference information is synonymous with background information. It is the source information you use to understand the basic elements of your topic, the terminology scholars use when discussing a topic and how it fits into a larger context. Academic encyclopedias and dictionaries form the backbone of a reference collection, but you might use other primary sources or commentary collected by your academic library to learn more about your research topic. Reference collections tend to be separated from other collections physically and digitally. They are intended to be used like Wikipedia, for understanding a topic, but not necessarily as the final destination for inquiry. Unlike Wikipedia, most professors are fine with students quoting and citing academic reference resources. This is because reference resources are written or edited by academics, scholars, scientists, researchers and other experts. However, students should not stay in a reference collection if they want to go deeper into a research topic.

Books

Books have been a staple of academic research since Gutenberg invented the printing press. Most academic books come out of traditional publishers with clear editorial review policies. Research in the humanities and social sciences, which include academic disciplines such as anthropology, literature and history, are primarily published in this format. A book can cover a research topic deeper than most other information sources. Books will give you a full picture of the topic, event or controversy you are researching. They can give you the context of a research topic, detailing the history and current situation we find ourselves in. Books tend to be the culmination of long term research and investigation, so you can mine a book’s bibliography or works cited pages for scholarly journal articles, research studies, government reports, experts in the field or other books. Also, academic books give you clear connections to disciplinary thinking on a topic, giving you insight into the important academic theories, scholars, research experiments or foundational knowledge of which you should be aware.

Newspaper and Magazine Articles

Magazine and newspaper articles are typically written by journalists who report on an event they have witnessed firsthand or after they make contact with those more directly involved. Journalists focus on information that is of immediate interest to the public and they write so that a general audience can understand the content. In research, newspaper articles are often best treated as primary sources, especially if they were published immediately after a current event. (See the GATHER chapter for more information about primary sources.) Magazine articles and longer investigative newspaper articles tend to explore why something happened, usually with the benefit of a little hindsight. Writers of these long form articles rely heavily on investigation and interviews for research. Journalists tend to be equal opportunity consumers of academic, government and popular information resources. This blending of resources makes their work more accessible for students exploring a topic or looking for a direction to take their research. Newspaper and magazine articles are considered popular resources rather than scholarly resources, which gives them less weight in academic work.

Scholarly Articles

Scholarly articles are written by and for experts in an academic field of study. They typically describe original research conducted to provide new insight to an academic field of study. You may have heard the term “peer review” in relation to scholarly articles. Peer reviewed articles undergo a review process carried out by professional researchers, academics and industry experts. This group checks the accuracy of the information presented in a scholarly article and the validity of the research methods used to conduct the research behind the findings. This peer review process adds a level of credibility to scholarly articles that you would not find in a magazine or news article. Scholarly articles tend to be long and feature specialized language that is meant for an expert audience. They provide the framework for researchers and scholars to build new original research projects. Scholarly articles carry a lot of weight in scholarship and professors often require their use in undergraduate assignments.

While scholarly journal articles are typically required for students doing college level research projects, they are not a great place to start your research. By their nature, scholarly journal articles are narrowly focused on one particular study or research project. It takes several studies to start drawing conclusions about a social phenomenon, scientific theory, law of nature or other piece of the academic cannon. As a novice to a field of study, an undergraduate student should start formulating their research question, research topic, and narrow research focus before they dive into scholarly journal articles.

When searching databases for scholarly journal articles, it is a good idea to have a few different arguments or points you want to make about your topic. Having more than one argument or line of reasoning ensures that you can use different studies for different points you want to make. It also forces you to find scholarly articles that come to slightly different conclusions or design their experiments in slightly different ways.

Government Information

Some academic libraries are depository libraries for the Federal Depository Library Program and collect specific documents or publications from different government agencies; most are not. All academic libraries collect or curate government information, in print or digital formats, that is useful to their campus communities.

Government information consists of any information produced by local, state, national or international governments and is usually available at no cost. However, it can be reproduced by a commercial entity with added value and cost. To use free government information, look for websites that are created by official government entities such as the US Department of the Interior, UNESCO, the State of Ohio or the Library of Congress. You can typically conduct searches of the official websites or use databases and tools developed by a government agency to search different kinds of information. For example, the United States Congress has a searchable database of legislation and proposed bills. The US Census Bureau has a searchable database to help you explore census data. Another way to access free government information is to use web portals developed by official government agencies. Web portals are websites that bring together information of many different formats into one uniform search. USA.gov is a large federally developed web portal that brings together information and services from many different government agencies across the United States. Many academic libraries have research guides or links to relevant government information, databases, tools and portals.

Government information can help students understand the history, policies, legislation, programs, regulations, or agencies involved in a research topic. Sometimes the government is a key player in our research interests. In this case, government information can be treated as primary source information. Many government agencies conduct original research, this can be published as government reports or scholarly journal articles. In this case, government information can be used as evidence to prove or disprove a theory or hypothesis. Many government officials have demonstrated expertise and first-hand experience with our research topic. In this case, government information can lend us credible expert opinion or commentary on our research topic. Government information is useful and vast, students should approach government information with a clear research topic or research question in mind to avoid overload.

Library Catalogs

A library catalog is a database that contains all of the items located in a library as well as all of the items to which the library has access. It allows you to search for items by title, author, subject, and keyword. A keyword is a word that is found anywhere within the record of an item in the catalog. A catalog record displays information that is pertinent to one item, which could be a book, a journal, a government document, or a video or audio recording.

If you search by subject in an academic library catalog, you can take advantage of the controlled vocabulary created by the Library of Congress. Controlled vocabulary consists of terms or phrases that have been selected to describe a concept. For example, the Library of Congress has selected the phrase “Motion Picture” to represent films and movies. So, if you are looking for books about movies, you would enter the phrase “Motion Picture” into the search box. Controlled vocabulary is important because it helps pull together all of the items about one topic. In this example, you would not have to conduct individual searches for movies, then motion pictures, then film; you could just search once for motion pictures and retrieve all the items on movies and film. You can discover subject terms in item catalog records.

Many libraries provide catalog discovery interfaces that provide cues to help refine a search. This makes it easier to find items on specific topics. For example, if a student enters the search terms “Hydraulic Fracturing” into a catalog with a discovery interface, the results page will include suggestions for refinements including several different aspects of the topic. The student can click on any of these suggested refinements to focus their search.

Locating resources in the library

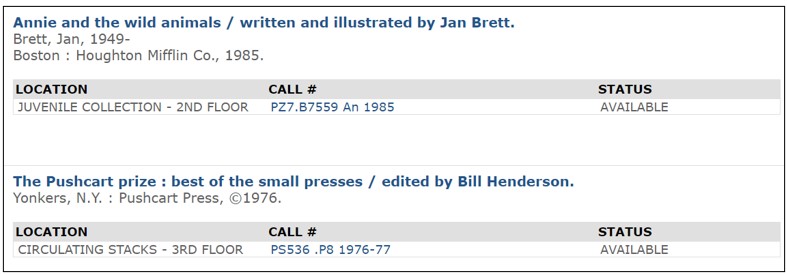

Using the library catalog, you may find several good resources on your topic, then you need to locate those resources. The catalog will provide you with information about the location of a resource. For example, the image below shows the Legacy Library catalog record with the location and the call number for the resource.

Where Can You Find Help?

The librarians at Legacy Library are there to help you when you have questions about searching for a source. Although single libraries can’t hope to collect all of the resources available on a topic, fortunately, libraries are happy to share their resources and they do this through OhioLink and interlibrary loan.

OhioLINK member libraries from across Ohio share books, periodicals, electronic resources and other items. You can find these in the Legacy Library OhioLINK catalog. You can view and/or check out these resources directly through the Legacy Library site.

LEARNINGACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Resources: Watch the video, “Intro to OhioLINK” to learn more about this service

Interlibrary loan (ILL) allows you to borrow books and other information resources from other libraries that are not necessarily part of OhioLINK. If you know that a book exists, ask your library to request it through their interlibrary loan program and have it delivered to the Legacy Library for your use. To learn more about Interlibrary Loan, email ill@marietta.edu. ILL service is available at both academic and most public libraries.

LEARNINGACTIVITIES & RESOURCES at the end of this chapter

Resources:To learn more about Interlibrary Loan, visit Legacy Library’s ILL FAQs and Tutorials webpage.

There is a wealth of knowledge contained in the resources of academic and public libraries throughout the United States.

How to Be a Strategic Researcher

It is a good idea to run your research topic by a professor or librarian to get recommendations about scholars, experiments, literature reviews, ethnographies, or scientific studies that might be important to your understanding of the topic.

In the scenario above, Mohamed also has been learning about how information is created and disseminated across American society and what academic libraries collect. This knowledge should help him find academic books and scholarly journal articles on his research topic. More importantly, this information should help him be strategic about what to collect and when. He has learned:

- The first thing he should do is gather background information and develop a research question. You can review Chapter 1: Identify if you need help with topic development.

Once he is focused, he has to make decisions about where to look for information on his research topic.

- He might immerse himself in popular magazines and newspapers to understand what the conversation about Muslims in America looks like to everyday people. He may look for an academic book that deeply explores this topic, sets up a framework for understanding this topic and maybe even points to relevant scholars or research on this topic.

- Mohamed will definitely need to find scholarly journal articles, but he should do that when he has several answers to his research question that he wants to verify or find evidence to support.

- Government information may or may not be important to his research; fortunately, he does not have to make that decision right away.

Additional chapters in this guide discuss important knowledge, techniques and skills needed to navigate the physical and digital collections in an academic library.

Learning Activities & Resources

Exercise 2A: Using the Information Cycle as a Guide

For each event listed in the left column in the table below, refer to the Information Cycle to determine where might be the best place(s) to begin looing for information. Check each box that applies.

| EVENT | SOCIAL MEDIA, TV, the WEB | NEWSPAPERS or POPULAR MAGAZINES | SCHOLARLY JOURNALS, | BOOKS, GOVERNMENT PUBLICATION |

| Yesterday’s fire in Chicago | ||||

| World War II | ||||

| The latest mass school shooting | ||||

| The outbreak of the war in Ukraine | ||||

| Last week’s political news | ||||

| Queen Elizabeth’s death in Sept. 2022 |

Resources

For more about The Information Cycle, watch the YouTube video “The Information Cycle,” by USC libraries. (https://youtu.be/xQxUHCDHEv4)

Take a Video tour of Legacy Library. Watch the video “Legacy Library Video Tour.”

(https://library.marietta.edu/c.php?g=836257&p=5972111)

For more Information about OhioLINK, watch the video “Intro to OhioLINK,” by Marietta’s Legacy Library.

(https://library.marietta.edu/c.php?g=836257&p=7674259)

To learn more About Interlibrary Loan, visit Legacy Library’s ILL FAQs and Tutorials webpage.

(https://library.marietta.edu/ill-help)