Main Body

The Rise and Fall of WorldCom

The rapid rise and even faster crash of WorldCom contrasts the successes and failures of capitalism, detailed by poor management and greed followed by moral courage. It is a story of how one person can change the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, for better and for worse.

Industry Background

The market forces that enabled WorldCom were rooted a century earlier, with Alexander Graham  Bell’s invention of the telephone in 1875. Bell then founded the Bell Telephone Company in 1877. Within a decade, over 150,000 people in the United States owned a telephone. The population at that time was just over 50 million, so the market still had great opportunity to grow. Bell Telephone grew to operate local phone systems throughout the United States. In 1885 the company created a subsidiary known as the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (later known as AT&T), with the intent of creating a long distance network. Bell Telephone became the monopoly provider of both local and long distance phone service and in 1908 introduced the slogan “One System, One Policy, Universal Service.”

Bell’s invention of the telephone in 1875. Bell then founded the Bell Telephone Company in 1877. Within a decade, over 150,000 people in the United States owned a telephone. The population at that time was just over 50 million, so the market still had great opportunity to grow. Bell Telephone grew to operate local phone systems throughout the United States. In 1885 the company created a subsidiary known as the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (later known as AT&T), with the intent of creating a long distance network. Bell Telephone became the monopoly provider of both local and long distance phone service and in 1908 introduced the slogan “One System, One Policy, Universal Service.”

The recognition of the company’s monopoly came in 1913 when AT&T settled a federal anti-trust lawsuit. The result of this lawsuit was that AT&T was officially approved by the U.S. government as a monopoly. From 1915 to 1947 the company went on to create important technologies in radio, television, science, broadband, mobile telephones, and electronics, earning several researchers the Nobel Prize in Physics. In 1949, the United States Justice Department filed an anti-trust suit attacking AT&T’s monopoly position in local and long distance phone service. In the 1956 settlement agreement, AT&T agreed to not pursue other lines if business and to limit its business other than activities to local and long distance phone service, as well as contracted projects for the U.S. government.

After almost a century of AT&T’s monopoly power over telephone service, in 1974 the federal government brought another anti-trust action against AT&T. In 1982, the settlement required AT&T to divest itself of all local phone service, creating seven Regional Bell Operating Companies (RBOCs) in 1984:

- Ameritech

- Bell Atlantic (which became Verizon in 2000)

- BellSouth

- NYNEX

- Pacific Telesis

- Southwestern Bell

- US West

The result was the largest breakup of a monopoly in U.S. history. The divestiture of the RBOCs in 1984 left AT&T solely in the business of long distance service, but the settlement agreement with the federal government lifted the restrictions in the 1956 settlement, allowing AT&T to pursue other business ventures, including cell phone service. Through a series of mergers, four of the seven RBOCs would later become part of AT&T once again.

The 1984 breakup of AT&T, along with its monopoly position, opened the door for many new competitors in the telephone industry, including WorldCom.

The Napkin Birth of WorldCom

In 1982, after hearing of the AT&T settlement and the effective deregulation of the telephone industry, two local entrepreneurs in Hattiesburg, Mississippi explored the business opportunities. Murray Waldron and William Rector checked their local chamber of commerce and found no long-distance competitors to AT&T in their local community. They met at a coffee shop in Hattiesburg to discuss the business possibilities. They asked a waitress if she had a suggestion for a business name. After a few minutes she returned with the suggestion Long Distance Discount Calling (LDDC). They modified the name to become Long Distance Discount Service (LDDS). To fund their new venture, Waldron and Rector found Bernie Ebbers, a successful local businessman. None of the three men knew anything about the long-distance business, but they saw an opportunity.

Who is Bernard J. Ebbers?

Bernard “Bernie” Ebbers was born in Edmonton, Canada. In his early years, the family moved to California and New Mexico, where he spent five years in a Navajo boarding school. In his teenage years, Bernie’s family returned to Edmonton, where he finished high school. After high school, he attended University of Alberta for just one year due to poor grades. Ebbers was a poor student, but he was an excellent basketball player and had ambitions to succeed.

In his 20’s, Bernie worked a variety of odd jobs including loading bread trucks, delivering milk, and working as a bouncer at a local bar. He then landed a job teaching high school basketball. His basketball skills earned him a basketball scholarship to Mississippi College, a Baptist college in Clinton, Mississippi. At age 25 he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in physical education. After graduation, he worked in a garment factory in Brookhaven, Mississippi, where he learned the importance of tightly managing business expenses.

In 1974, Ebbers bought a motel in Columbia, Mississippi. He and his wife lived in a trailer in the motel parking lot. Bernie used his on-the-job knowledge of cost management in the garment factory to tightly manage the expenses of his motel. He also owned a KOA campground. He then founded a company to manage hotels and motels for investors who were attempting to find new owners for their properties. Ebbers was successful in business and was able to accumulate some modest wealth. This wealth enabled him to be the financial investor for LDDS.

The Growth Years

LDDS starting selling long distance service in January, 1984. It was easy to find business customers, but LDDS was poorly managed and lost approximately $300,000 in 1984 due to poor cost management. Some of the founding partners felt that the business would soon fail. Bernie Ebbers then assumed management control of LDDS. He applied his experience with expense management and turned the company around. Due to Ebbers’ cost cutting and detail-oriented management, LDDS turned around quickly and became profitable. Murray Waldron, one of the founding partners, said Bernie was “just as tight as old Scrooge when it came to spending money.”

but LDDS was poorly managed and lost approximately $300,000 in 1984 due to poor cost management. Some of the founding partners felt that the business would soon fail. Bernie Ebbers then assumed management control of LDDS. He applied his experience with expense management and turned the company around. Due to Ebbers’ cost cutting and detail-oriented management, LDDS turned around quickly and became profitable. Murray Waldron, one of the founding partners, said Bernie was “just as tight as old Scrooge when it came to spending money.”

With the company now profitable, Bernie began to acquire other small long-distance companies. Within four years, the company had operations in four states. Bernie’s management style also was changing from detail-oriented to paying little attention to the detail with a significant focus on acquisitions. The primary goal in the first few years was to build the company and then sell to a larger competitor. That goal changed because the acquisition strategy was working well. In 1989, LDDS became a publicly-traded company. In just four years, LDDS grew from a near-failing company to going public. This public offering would provide LDDS with yet another tool for expansion – using its own stock as currency for acquisitions. Some of the most important acquisitions included:

1992 – LDDS merges with Advanced Telecommunications Corporation (ATC), paying the entire purchase price with LDDS stock. One of the ATC employees, Scott Sullivan, would become the Chief Financial Officer at LDDS in two years. Sullivan would play a major role in the WorldCom fraud that followed in later years.

1993 – LDDS acquired two other companies in an all-stock purchase. The acquisitions of Resurgens Communications Group Inc. and Metromedia Communications Corp. would result in LDDS becoming the fourth largest long-distance provider.

1994 – With the $900 million all-stock purchase of IDB Communications Group Inc., LDDS obtained a significant foothold in the international long-distance business.

1995 – LDDS acquired Williams Telecommunications Group Inc. (WilTel) for $2.5 billion in cash. The acquisition of WilTel gave LDDS, for the first time, its own network of fiber-optic local communication lines. Prior to the WilTel acquisition, LDDS only leased communication lines from larger carriers. With this acquisition, WorldCom became the fourth largest long distance provider, ranked as follows:

| Company | Market Share |

| AT&T | 59% |

| MCI | 19% |

| Sprint | 10% |

| LDDS | 5% |

Shortly after the WilTel merger, LDDS changed its name to WorldCom.

1996 – WorldCom merged with MFS Communications, allowing WorldCom to acquire UUNet, a major internet service provider. The acquisition price of $12 billion was paid for entirely with  WorldCom stock. With this acquisition, WorldCom now had a presence in the long-distance market, the local market, and internet service, allowing WorldCom to be a “one-stop shop” for communications services.

WorldCom stock. With this acquisition, WorldCom now had a presence in the long-distance market, the local market, and internet service, allowing WorldCom to be a “one-stop shop” for communications services.

By the end of 1996, WorldCom had grown to a significant competitor with 19,000 miles of fiber-optic fiber lines and business in 50 countries.

1998 – British Telecom offered to buy MCI for $19 billion. Within weeks, WorldCom announced that it had beaten British Telecom and would be acquiring MCI for $37 billion, nearly double what British Telecom had offered. The acquisition was the largest corporate merger in history, but gave WorldCom a strong presence in the consumer telephone market. MCI was much larger than WorldCom, making this an unusual acquisition with the small fish swallowing the big fish. The Economic Policy Institute labeled this as the “bad deal of the century.” The U.S. Justice Department approved the merger, but told Bernie Ebbers that any further acquisitions would be more difficult to get Justice Department approval.

After the MCI merger, WorldCom changed its name to MCI WorldCom, although the company continued to be colloquially known as WorldCom.

1999 – The Wall Street Journal reported on October 5, 1999 that MCI WorldCom and Sprint had agreed to merge in a deal that would require MCI WorldCom to pay $115 billion in stock for Sprint. The deal would result MCI WorldCom having 30 million long distance customers (a 30% market share) and a significant presence in the wireless cell phone market. The U.S. Justice Department filed an anti-trust lawsuit in opposition of the merger. European regulators were planning on filing a similar anti-trust case, but in July, 2000, MCI WorldCom and Sprint announced they were cancelling their merger under pressure from U.S. and European regulatory authorities.

The cancelling of the Sprint acquisition in 2000 effectively ended MCI WorldCom’s long strategy of growth through acquisitions. MCI WorldCom’s 1998 annual report indicated total liabilities of over $37 billion, incurred mostly due to the MCI acquisition.

Indigestion of Acquisitions

Corporate history has many cases of acquisitions and mergers. Some are done well, and some are not. But acquisitions are almost always difficult. Brining two companies together requires integrating different cultures, products, technologies, management, employee teams and financial reporting. WorldCom was particularly challenged because there were so many mergers and in later years those mergers were very large. MCI was much bigger than WorldCom. At that time this was the largest corporate merger in history. By 1999 the company had completed over 70 acquisitions, including 65 acquisitions in the most recent six years, but had not integrated them well. There were problems with sales, customer service, and other areas.

Each acquired company had a separate sales force. When a potential customer was considering buying communications services, several different WorldCom sales representatives might compete against each other. Essentially, the company was competing against itself to offer the lowest price.

Some customers used WorldCom for multiple services, such as long distance, local service, or internet service. If a customer called about an issue on their internet service, the WorldCom representative would tell the customer that there was no record of them being a customer. After a few questions, the WorldCom employee would advise the caller that they were a customer of another WorldCom unit and would tell the customer to call the other customer service department.

CEO Bernie Ebbers was focused on new acquisitions and did not devote his attention or adequate effort toward integrating prior acquisitions. With so many poorly integrated acquisitions, by the late 1990’s WorldCom was out of control.

Internet Growth is good, But Not That Good

The late 1990’s was a time of explosive growth in the internet, and WorldCom was well positioned to participate in that growth. The term “internet” was used as a label in 1984 and the World Wide Web that we see in URLs for websites as www emerged in 1989. The era of e-commerce started in 1995. WorldCom‘s 1996 buyout of MFS Communications and UUNet, a major internet service provider, established WorldCom as a major industry competitor.

In 1997, a WorldCom capacity planner named Tom Stluka developed an Excel spreadsheet that could be used to forecast growth in internet sales. Like any good spreadsheet, Stluka allowed for the assumptions to be changed to test various scenarios. One critical assumption in a scenario was the rate at which internet use was growing. On one iteration, he used the assumption that internet would double every 100 days. There was no basis in fact or history for this assumption. It was merely a best-case scenario simulation, which would greatly benefit the companies who carried the internet traffic, including WorldCom. Unbeknownst to Stluka, that “what-if” scenario was to become acknowledged as an accepted fact. Approximately one year after Stluka tested the scenario, he heard analysts publicly repeat the growth projection. The assumption was accepted by other companies, by the government, and by a presidential candidate. The assumption of the internet doubling every 100 days, or 1,000% per year, even appeared in WorldCom’s 1998 annual report. Stluka attempted to tell WorldCom executives that the assumption was not realistic, but they did not accept his warning. According to Stluka, that is when he started saying “the emperor has no clothes, because nobody wanted to look at the truth.”

The general acceptance of the assumption that internet traffic would double every 100 days caused WorldCom and other competitors to expand fiber optic networks rapidly. According to C. Michael Armstrong, the then-CEO at AT&T, they were laying 2,200 miles of fiber-optic cable every hour to meet the demand that was based on the false assumption of astronomical internet growth. While this was great business for the manufacturers and installation contractors, the result was an overbuilt capacity that would far exceed the demand for internet traffic.

The Dotcom Crash

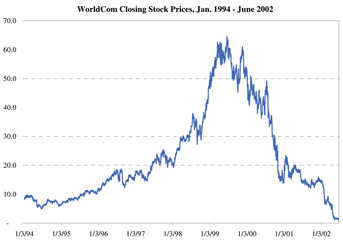

There is an analogy that says during the California gold rush, the true profit was made by the merchants that sold picks and shovels to the miners, but most miners made little money. This analogy  applied well to the internet boom of the late 1990’s. Some companies were new “dotcom” companies that lost vast amounts of money every year, with no hope of ever making a profit. But the purveyors of cable, routers, switches, etc. earned huge profits and had a more sustainable business model. WorldCom had one of the more sustainable business models. Any company associated with the internet or technology experienced rapid increases in stock price. Those stock prices were well beyond any reasonable historic stock prices. The result was the dotcom crash of 1999-2000. WorldCom was affected by the dotcom crash as well, with the stock price falling by 30% from just under $26 per share in February, 1999 to $18 per share in April, 2000.

applied well to the internet boom of the late 1990’s. Some companies were new “dotcom” companies that lost vast amounts of money every year, with no hope of ever making a profit. But the purveyors of cable, routers, switches, etc. earned huge profits and had a more sustainable business model. WorldCom had one of the more sustainable business models. Any company associated with the internet or technology experienced rapid increases in stock price. Those stock prices were well beyond any reasonable historic stock prices. The result was the dotcom crash of 1999-2000. WorldCom was affected by the dotcom crash as well, with the stock price falling by 30% from just under $26 per share in February, 1999 to $18 per share in April, 2000.

Bernie Ebbers Pay, Spending, and Debt

As with many CEOs, Bernie Ebbers was well paid but much of his compensation came from stock-based compensation. In 2000, Ebbers received over $34 million in total compensation (even though it was a tough year for WorldCom). In 1999, Forbes listed him as one of the 200 wealthiest Americans with an estimated net worth of $1.4 billion. These were the fruits of building a Fortune 500 company from nothing in just five years. Almost all of his wealth was in WorldCom stock.

Ebbers liked to spend his wealth on real estate including 540,000 acres of timber, a Louisiana rice and soybean farm with 21,000 acres, and a 500,000 acre ranch in British Columbia with 20,000 cattle and a resort. With most of his wealth tied up in WorldCom stock, Ebbers needed to borrow money to finance these purchases. Like WorldCom’s extensive use of debt, Ebbers incurred substantial debt in his personal life. To finance the real estate, he borrowed as much as possible with mortgages and then used his WorldCom stock as collateral for even more loans.

Loans against stock are known as “margin loans.” The problem with a margin loan is that it cannot exceed 50% of the value of the stock. If the stock price declines, the borrower must pay cash to reduce the loan. For example, a person could borrow $500 against stock worth $1,000. But if the stock value fell to from $1,000 to $600, the loan could not exceed half of the new value, or $300. The earlier loan of $500 would no longer be permissible, and the borrower would have to pay cash of $200 to reduce the loan to the new limit of $300. If this is not done promptly, the stock must be sold to generate the cash needed to reduce the loan. This is known as a “margin call.” As WorldCom’s stock declined in price, Bernie’s stock valuation was no longer sufficient to support the loans. He was faced with the need to sell stock in order to generate cash to pay down the margin loans.

The WorldCom board of directors did not want Ebbers to sell his stock, fearing that large sales of stock would drive the stock price down. Also, it would send a message to the stock market that the CEO no longer believed in the company. This would cause other investors to sell their stock as well, further driving down the stock price. To avoid the need for Ebbers to sell his stock, the Board of Directors lent him $341 million, with an interest rate of just over 2%. This was the largest loan ever from a public company to its CEO.

The Perfect Storm

By the year 2000, everything seemed to be going wrong at WorldCom.

- The growth through acquisition strategy could not continue

- Acquisitions were poorly integrated

- The company had acquired substantial debt

- The stock price was declining

- Some accounting gimmicks that were easily used and covered up were no longer available

- The company needed to meet analyst projections of growing profits to keep the market happy, but the company was actually losing money.

- CEO Bernie Ebbers was in personal financial trouble

The only choices available to the company were:

(1) accept the reality of their changed financial situation

(2) find new ways to grow

(3) use financial statement fraud to fool the market

Aggressive Accounting and Fraud Methods

WorldCom had been using some aggressive accounting techniques before the tough times of 2000. These may have started company executives down the slippery slope to what would eventually become financial statement fraud. One of the principles of accounting is conservatism, which requires that estimates be applied conservatively so as to not mislead a user of the financial statements. WorldCom violated the principle of conservatism, but even went further into fraud.

Big bath

One aggressive accounting technique the company used was taking a “big bath” after acquiring another company. There are always costs of merging two companies and these are expenses in the year of the merger. This is acceptable accounting. Investors typically don’t care very much about these one-time costs, but are more concerned with future profits. The result is that the stock price does not typically fall very much, as investors don’t react to the one-time-only cost and sell their stock. WorldCom would use this opportunity to move expenses from future years into the current year to write off future expenses as a current one-time cost.

Taking the “big bath” would overstate expenses of the acquisition year and decrease expenses of future years. The result would be lower net income in the acquisition year and higher net income in future years. This would give the illusion of growing profits.

Cookie jar reserve

Similar to the big bath, WorldCom would reclassify some assets as research and development, which would be expensed in the current year. This technique would be used when profits exceeded analysts’ expectations, lowering profits of the current year. This may seem like an odd objective, but this overstated estimate would create a “cookie jar” reserve. In future years the costs could be revised downward, thus increasing profits in future years if profits should fall below expectations.

MCI Assets

During most acquisitions, the price paid by the acquiring company is higher than the value of the tangible assets of the company being purchased. This excess amount is basically paying for brand value, expected future profits, intellectual property, etc. The excess amount is known as “goodwill.” While the tangible assets and goodwill are both assets, they are accounted for differently. Tangible assets are expensed over their useful life through depreciation expense. Goodwill is expensed differently. Prior to 2001, goodwill was expensed over a period of up to 40 years. After 2001, goodwill no longer needs to be expensed at all. The expensing of the tangible assets and goodwill basically results in lower expenses for goodwill. WorldCom abused this difference to their advantage.

After acquiring MCI, WorldCom needed to allocate the total cost of MCI between tangible assets and goodwill. Both would be assets on the balance sheet, but the part allocated to goodwill would have lower future expenses. WorldCom deliberately allocated too much of the purchase price to goodwill and too little to tangible assets. This would have the effect of understating reported expenses in future years, thus overstating reported net income.

Understating uncollectible accounts

When the Sprint merger was denied, WorldCom lost the ability to use acquisitions as a way to hide expenses through “big bath” or “cookie jar” techniques, so they turned to other methods which were clearly fraudulent. Sometimes customers do not pay their accounts receivable as hoped. Some of these accounts would never be collected and needed to be written off. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles require that companies estimate how much of their accounts receivable will not be collected. These uncollectible accounts are recorded as:

- An “allowance for uncollectible accounts” which is basically a reduction in the net amount of the asset accounts receivable, thus reducing assets with a corresponding increase in equity on the balance sheet, and

- A “bad debt expense” that increases expenses and reduces net income on the income statement.

The amount to be recorded is an estimate, which must be based in reasonable assumptions. However, because it is just an estimate it can be abused by overstating or understating the amount of the estimate. If the estimate is overstated, in future years it can be adjusted downward to a more accurate level.

The overstatement would have the effect of reducing net income in the first year, but allowing a cookie jar reserve that could be tapped in later years. WorldCom chose instead to understate the estimate, thus making current year expenses lower and net income higher. This technique was fraudulently used by MCI prior to being acquired by WorldCom, and was continued at WorldCom until the year 2000. For more information, read the WebQuest link to the June 10, 2002 article “Ring of Thieves” in Forbes Magazine.

Line costs

LDDS, and later WorldCom, sold long distance service but did not own the telephone lines that would be used to carry the calls. Instead, the company would pay fees to other carriers for the use of their  phone lines. The cost of the fees was a normal operating expense and should have been recorded on the income statement in the year the lines were used. Instead, WorldCom categorized the line costs as “pre-paid capacity,” an asset. This moved the cost from the income statement to the balance sheet. On the income statement, expenses were lower and net income was higher. The balance sheet would have higher assets and owners’ equity. This was fraudulent financial reporting.

phone lines. The cost of the fees was a normal operating expense and should have been recorded on the income statement in the year the lines were used. Instead, WorldCom categorized the line costs as “pre-paid capacity,” an asset. This moved the cost from the income statement to the balance sheet. On the income statement, expenses were lower and net income was higher. The balance sheet would have higher assets and owners’ equity. This was fraudulent financial reporting.

Even though it made the first year look much better, the line cost asset on the balance sheet needed to be expensed in future years, thus lowering future profits. According the the SEC’s June 2002 complaint against WorldCom, in 2001, the company misclassified $3.06 billion of line costs in order to make it appear that the company made a 2001 profit of $2.393 billion. But, if accounted for correctly, WorldCom actually lost $662 million. This same technique was used in the first quarter of 2002 to make it appear that quarterly profit was $240 million, but they actually lost $557 million.

How the Fraud was Uncovered

The discovery of the fraud by WorldCom’s internal audit department is a story in ethical determination and moral courage, in the face of threats, obstacles, and adverse outcomes for the auditors. The most common way frauds are detected is through employee tips. In this case there were four key players in detecting the fraud:

- Kim Emigh, WorldCom Financial Analyst

- Mark Abide, WorldCom Director of Property Accounting

- Glyn Smith, WorldCom Director of Internal Audit

- Cynthia Cooper, WorldCom Vice President of Internal Audit

Kim Emigh

Kim Emigh worked in the networking engineering department for WorldCom in Richardson, Texas. Even prior to 2001, Emigh had repeatedly questioned WorldCom’s accounting practices and raised the issue of potential overcharging or kickback schemes involving WorldCom vendors. In 2002, he was directed by WorldCom management to reclassify $3.5 million in expenses to better match the department’s budget. After raising objections, Emigh was fired from WorldCom.

Mark Abide

At the criminal trial against CEO Bernie Ebbers, Mark Abide testified that in April 2002 he had been ordered by his supervisor to make fraudulent journal entries in WorldCom’s accounting records that would reclassify line costs from an operating expense as a capital asset. Other accounting department staff apparently had been making similar entries for over a year. Abide testified “I kind of went off and said no way was I going to start booking that entry. I had asked all the way up, and I didn’t get any support or any backup, and I wasn’t going to start booking it,” He went on to testify that his colleagues and supervisor “were silent for a minute, and then they said they understood.”

A few weeks after Abide refused to make fraudulent entries, he read a May 21 article in the Fort Worth Weekly that detailed Kim Emigh’s allegations of expense reclassifications in the Richardson office. On that same day, Abide sent an e-mail to internal auditor Glyn Smith suggesting that Emigh’s allegations might be worth looking into. Abide did not mention the request he himself had received to make fraudulent journal entries, but instead hoped the internal auditors would do an expanded audit of WorldCom’s capital expenditures and then find the fraudulent entries in Abide’s own department.

Glyn Smith

Glyn Smith, a Director of Internal Audit reviewed the e-mail and article he received from Mark Abide. He then took it to Cynthia Copper, the Vice President of Internal Audit. The internal audit department was scheduled to examine capital expenditures later in the year and they decided to get an early start on that project.

Cynthia Cooper

In the early stages of the audit, one of the internal auditors ran a report where they could only see the balance sheet side of the journal entries.

Unbeknownst to the auditors at the time, one of the controllers had secretly restricted the auditors’ access to the IT accounting system. The missing entries caused the auditors to look further. During their review, the controller who was responsible for the journal entries in question told Cynthia Cooper she was wasting her time and should focus on other areas on the company. The audit committee chair told Cynthia to not investigate the journal entries and told her that CFO Scott Sullivan would be calling her.

Cynthia Cooper received an unusual call from Scott Sullivan, asking Cooper to meet him in his office in ten minutes. During that meeting, Sullivan told Cooper to delay the audit of capital expenditures. He also said that he was holding up all promotions in the internal audit department until he understood what they were doing. He also said that one member of the audit committee who was from the Board of Directors had been removed from the audit committee. This effectively eliminated Cooper’s direct access to the Board. Cooper said she felt that meeting was non- consistent with Sullivan’s character, raising more concerns and questions.

In her book, Extraordinary Circumstances: The Journey of a Corporate Whistleblower (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2007), Cooper states that she remembered at a young age her mother telling her not to be intimidated. The audit pressed forward in defiance of Sullivan’s order. The audit team worked nights and weekends to avoid suspicion. They ran data queries on the IT system that were so extensive they crashed the system. In the end, they discovered the fraudulent journal entries, done by accountants reporting to CFO Sullivan. Cooper then brought her findings to the attention of Melvn Dick, the Arthur Andersen partner in charge of the external audit of WorldCom’s financial statements. The partner stated that the over and under amounts in various accounts throughout the company tended to balance each other out. He dismissed her concerns. When she raised the issue with Scott Sullivan, he said the same thing the Andersen partner said, that everything companywide balanced out. Cooper was more concerned with Sullivan’s demeanor in this meeting, which she described as aggressive and hostile. Sullivan also verbally reprimanded her for discussing the issue with the Andersen partner.

In spite of the road blocks from Andersen and Sullivan, Copper persisted in pressing the findings. The internal audit department requested and received Andersen’s work papers on the accounts in question. The internal audit review of Andersen’s work revealed that the over and under amounts did not balance out companywide. Sullivan and the Andersen partner were incorrect.

Within one month, the internal auditors finished their work and were ready to present it. They attended a meeting of the audit committee in Washington D.C. and presented their findings on June 20, 2002. The chair of the audit committee challenged Scott Sullivan for an explanation and gave him several days to justify the journal entries. A few days later, Sullivan provided a written justification for the journal entries, but the board was not persuaded. On June 24, 2002, the audit committee told CFO Scott Sullivan and controller David Meyers that they could either resign immediately or they would be fired. David Meyers resigned, but Scott Sullivan refused to resign and was fired. On June 25th, WorldCom announced publicly that profits from January 2001 to March 2002 had been overstated by $3.8 billion. Ultimately, the fraud would be found to be much larger.

Further Investigation

Once the fraud was uncovered, a thorough examination was required to determine the total fraud plus any other aggressive accounting. Prior years needed to be reviewed and previously issued financial statements had to be revised and reissued.

any other aggressive accounting. Prior years needed to be reviewed and previously issued financial statements had to be revised and reissued.

On March 11, 2002, before the fraud was discovered, the SEC opened an inquiry into WorldCom’s accounting practices and loans to officers. The next day the Wall Street Journal reported

“WorldCom said the SEC has asked for information about a broad range of items. These include: disputed bills and the sales commissions attached to them; a charge the company took in 2000 related to wholesale customers; key merger-related accounting policies; loans the company made to Chief Executive Bernard Ebbers; the company’s tracking of Wall Street earnings expectations; any other federal or state investigations; and the integration of WorldCom’s computers with those of the former MCI Communications Corp., which WorldCom acquired.

Some of the matters covered by the SEC request have been the subject of a WorldCom internal probe focusing on whether salespeople routinely double-booked sales in an effort to boost their own commissions. The internal audit, reported by The Wall Street Journal last month, already has led to the departures of three star employees, including two sales managers and one of its highest-grossing sales representatives, who WorldCom says claimed as much as $4 million in unauthorized commissions for sales that already had been booked by other divisions of the company.

Now, the SEC has asked WorldCom for any documents since January 1999 relating to “complaints by customers about overbilling,” “disputed sales commissions,” “inflated sales commissions” and “overbooking of sales.”[1]

On June 26, 2002, after the fraud was discovered, the SEC announced that it was expanding its investigation. The next day they filed civil fraud charges against WorldCom, even though the full amount if the fraud was yet to be determined. The SEC amended its fraud case on November 6, 2002, alleging fraud of more than $9 billion dating back to 1999.

With the discovery of the fraud and a new CEO and CFO at the helm, WorldCom began its own investigation of accounting practices. Outside help was needed and two experts were hired from AlixPartners, LLC to oversee the effort. Within a few months, the internal auditors quickly found an additional $3.8 billion, doubling their earlier estimate of accounting irregularities. The effort to audit the accounting irregularities was a massive effort requiring almost two years to complete, requiring up to 1,600 people and costing $365 million. The internal investigation revealed that the reported profit of $7.6 billion for 2000 and 2001 was really a loss of $73.7 billion.

In the end, the fraud was estimated at $11 billion, with the remainder in aggressive accounting assumptions.

The Effect on Key Individuals

Bernard Ebbers resigned as WorldCom’s CEO April 30, 2002, supposedly to manage the sale of his real estate holdings. Unlike prior fraud cases, the WorldCom perpetrators were given substantial prison time.

CFO Scott Sullivan and Controller David Meyers were arrested in August 2002. Meyers plead guilty immediately to conspiracy, securities fraud, and false regulatory filings. He agreed to serve as a cooperating witness against the other criminal defendants. Scott Sullivan was facing 25 years in prison, but vowed to fight the charges vigorously. However, on March 2, 2004, shortly before his trial, he also plead guilty and promised to testify against Bernie Ebbers. Both men were to receive lesser sentences in exchange for their cooperation. Sentencing for both Meyers and Sullivan was delayed until after the other cases were resolved.

On the same day Sullivan plead guilty, March 2, 2004, Bernie Ebbers was indicted. One year later, on March 15. 2005, Ebbers was convicted on all counts of conspiracy, securities fraud, and false regulatory filings. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. At age 63, this would effectively be a life sentence. In credit to Ebbers, he never sold any of his WorldCom stock. Some analysts speculate this was a sign that he was truly unaware of the fraud and the true state of WorldCom. As his stock collapsed, his assets were less than his debts. He is currently serving his term in the Oakdale Federal Correctional Complex in Louisiana.

After the Ebbers trial, Meyers and Sullivan received their sentences on August 10th.

Meyers was sentenced to one year and a day in prison. The extra day made him eligible for early release based on good behavior. He served nine months. After serving his time, he worked on private equity transactions and stared a consulting business. In 2010 he co-founded Ways, LLC, a home health agency with the help of federally-guaranteed loans of $74.5 million. He also has been a speaker on ethics at various colleges and universities. One of his presentations is called “The Slippery Slope: Learning from Someone Else’s Mistakes,”

Scott Sullivan received a sentence of five years in prison. He served four years at the Federal Correctional Institution in Jessup, Georgia.

Other convictions include Buford Yates, Betty Vinson, and Try Normand. Buford Yates, WorldCom’s director of general accounting, plead guilty to fraud and was sentenced to one year and a day in federal prison. Betty Vinson, a mid-level WorldCom accountant claimed she was pressured into making the entries. As another cooperating witness against Ebbers, she received a sentence of just five months in prison followed by five months of house arrest. Troy Normand, described by the prosecutor as the least culpable of the six convictions, was ordered three years of probation after he plead guilty to two counts of conspiracy and securities fraud.

For her efforts as a whistleblower, Cynthia Copper shared the cover of Time Magazine as persons of  the year for 2002 with Sherron Watkins of Enron and Coleen Rowley of the FBI. She stayed on at the company for another two years to help with the internal review and restatement of WorldCom’s prior financial statements. She then left the company to write her book mentioned earlier. In her book, Cooper describes the roller coaster of emotions she felt during the investigation as well as the history, process, and her suggestions for a more ethical corporate culture.

the year for 2002 with Sherron Watkins of Enron and Coleen Rowley of the FBI. She stayed on at the company for another two years to help with the internal review and restatement of WorldCom’s prior financial statements. She then left the company to write her book mentioned earlier. In her book, Cooper describes the roller coaster of emotions she felt during the investigation as well as the history, process, and her suggestions for a more ethical corporate culture.

WorldCom after the Fraud

The company was riding high on June 18, 1999 when the stock price hit $63.50. The stock price declined through the dotcom crash and then fell rapidly when the fraud was announced. WorldCom filed for bankruptcy protection on July 21, 2002. WorldCom settled investor suits on May 19, 2003 for $500 million, a small fraction of the losses the investors incurred. Six weeks later, on July 7, 2003, the bankruptcy court approved a $750 million settlement with federal regulators. On August 6, 2003 the court also approved an additional $750 million with the SEC to settle the civil fraud charges.

When the company emerged from bankruptcy on April 20, 2004, all of the common stock had been declared worthless, most of the debt had been dismissed by the bankruptcy court, and the company was renamed MCI.

On February 14, 2005, Verizon Communications Inc. announced its offer to acquire MCI. After beating Qwest Communications in bidding war for MCI, Verizon ultimately acquired MCI for $8.44 billion, a fraction of the company’s value prior to the fraud.

Related Settlements

Board of Directors

On January 8, 2005, ten WorldCom directors entered into a landmark settlement agreement against them individually for $54 million. For many years investors had complained that directors escaped liability for their poor governance of corporations. Prior cases against directors were paid by the company itself or by insurance that was paid for by the company. For the first time, this agreement required that the directors pay part of the settlement, $18 million, out of their own pockets.

Citigroup

There were allegations early on that Citigroup had encouraged investors to buy WorldCom stock, while simultaneously having a very close business relationship with WorldCom. The underlying allegation was that Citigroup should have known about the fraud. In early May, 2004, Citigroup wrapped up a lawsuit by stockholders and creditors by agreeing to pay $2.5 billion. At the time, this was the largest settlement ever paid by a financial firm or auditor to settle an investor lawsuit where such a conflict of interest was present. Later it would be discovered that the CEO of Citigroup collected $2 million as one of shareholder victims.

J.P. Morgan Chase

When WorldCom issued bonds in the two years prior to their bankruptcy, J.P. Morgan was a significant underwriter, helping WorldCom sell the bonds to investors. The plaintiffs in a class action suit against the bank alleged that J.P. Morgan Chase should have discovered the fraud during their due diligence in support of the bond offerings. In March, 2005, J.P. Morgan Chase agreed to settle this case for $2 billion.

Bank of America

Also in March, 2005, Bank of America settled a WorldCom investor lawsuit for $460 million. The allegations against Bank of America were the same as the allegations against Citigroup, that this underwriting bank promoted and sold WorldCom securities when they should have known that the company’s financial statements were fraudulent.

Arthur Andersen

As the outside auditor of WorldCom’s financial statements, Arthur Andersen was in a position of trust. Investors relied on Andersen’s clean opinion on the financial statements. It was alleged that Andersen failed to uncover the fraud. Andersen’s defense was that they followed auditing standards and had been misled by WorldCom management. In April, 2005 the audit form of Arthur Andersen agreed to pay $65 million to settle an investor lawsuit. In addition, Andersen agreed to give these investors 20% of any capital remaining after the Andersen liquidation. In October, 2012, that 20% supplemental payment was determined to be an additional $38 million.

Andersen Partners

On April 14, 2008, the SEC sanctioned two audit partners of Arthur Andersen, Melvin Dick and Kenneth M. Avery for improper professional conduct in their failure to follow Generally Accepted Auditing Standards. Both partners were prohibited from doing any work related to the SEC, including audits of public companies. Dick was banned for four years and Avery for three years. No other fines or penalties were assessed, and the partners did not admit any guilt or wrongdoing.

The above settlements were some of the more significant, but there were other class action cases and settlements as well. These cases totaled hundreds of millions of dollars.

Thousands or Workers Lose Their Jobs…and Investments

There were 88,000 employees at the peak of WorldCom’s success. Many workers were laid off after the company declined and entered bankruptcy. At the end of WorldCom’s bankruptcy there were just 55,000 workers. The 33,000 workers who lost their jobs, and their families, were devastated by the fraud. Not only did they lose their jobs, but any investment they had in company stock became worthless. On March 18, 2005, ABC News gave an example of one employee, Stephen Teel, who worked for MCI and then WorldCom for 23 years. At one point his WorldCom stock was valued at approximately $1,000,000, but after the collapse he garnered just $1,000.

WorldCom’s fraud and overly ambitious growth expectations for internet growth caused the entire telecom industry to expand far beyond the demand, resulting in an eventual collapse. In the telecom industry, 300,000 employees lost their jobs.

Investors Lose Everything – Almost

WorldCom’s stock price fell from over $60 in 1999 to zero after the bankruptcy. [2] Time magazine estimated in July 2002 that this fall cost investors approximately $175 billion.[3] Creditors to WorldCom lost an estimated $35 billion. The legal settlements provide fractional relief for investors. Altogether the settlements provide $6.1 billion of reimbursement to investors. The settlement would pay investors less than $1 per share, a very small recovery.

The Damage and Repair of the Capital Markets

The string of financial statement frauds hat included Sunbeam, Waste Management, Tyco, Global Crossing, Enron, WorldCom, etc. damaged investors’ faith on the capital markets. The capital markets are an essential fuel in the growth of a market-based system. Companies need to raise cash from issuing stocks and bonds. This cash is used to reinvest in new research, products, expansions, and the related hiring in all of these functions. If investors don’t have faith in a fair system, they will avoid the capital markets. Corporations will find it difficult to raise cash for expansion. The result would be a damaged economy and a lower standard of living for everyone. The high profile failures at WorldCom and Enron, preceded by other financial statement frauds, could have a devastating effect on the economy. To avoid loss of investor confidence, Congress adopted the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. This new law attempted to address the underlying causes of the major corporate scandals.

Internal Control to the Main Stage

One of the more significant sections of Sarbanes-Oxley is Section 404. This section requires management to include a certification with the financial report that:

- Affirms that management is responsible for establishing and maintaining internal control over financial reporting, and

- Contains management’s assessment of those internal controls.

The independent auditors are required to examine and attest to the accuracy of management’s assessment of internal control. Essentially, management must evaluate internal controls and the auditors must audit the management assessment. In many cases, companies hire a second CPA firm to perform management’s assessment of internal control and this is then audited by the CPA firm that gives an opinion on the financial statements.

The legislation that would become Sarbanes-Oxley was in process before the WorldCom fraud was fully known. Section 404 was added to Sarbanes-Oxley as a direct result of the failures at WorldCom.

Questions for Research and Discussion

1. What factors in the WorldCom case support the conclusion that CEO Bernie Ebbers knew about the financial statement fraud?

- What factors support his defense that he did not know about the fraud?

2. If the fraud had not been detected when it was, how long do you think it might have continued and how would it have ultimately been revealed?

3. Give suggestions on how the fraud at WorldCom could have been prevented? Think about what people at the company did, the company culture, and any roles others played in the fraud.

4. Which one person do you think is most responsible for the fraud being uncovered?

- Please explain your reasoning.

5. Six WorldCom employees were convicted in the case.

- Which of these do you believe is the most responsible for the fraud?

- Why?

6. If Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 had been in place before the fraud occurred, to what extent do you believe it would have prevented or reduced the fraud?

7. Compare and contrast the degree of moral courage exhibited by internal auditors Cynthia Cooper at WorldCom and Deidre DenDanto at Sunbeam.

8. The audit form of Arthur Andersen claimed they followed Generally Accepted Auditing Standards and were misled by WorldCom executives, yet they settled the investor lawsuits and two partners were sanctioned.

- What audit test do you believe Andersen could have performed to detect the fraud?

- Why did you choose those tests (use examples from the case)?

To report more than you actually have.