Main Body

The Chainsaw Al Massacre at Sunbeam Corporation

Pre-Massacre History

The roots of Sunbeam Corporation begin in 1897 when John K. Stewart and Thomas Clark incorporated the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company, which made sheep shears and horse trimmers. The company began their line of electric household appliances in 1910, using the brand name “Sunbeam.” Throughout the twentieth century the company continued to grow by creating and manufacturing new products and by strategic acquisitions of other companies. By 1955, Sunbeam was ranked by Fortune Magazine as the 317th largest corporation in America. The company continued to grow until being acquired by Allegheny International in 1981.

Sunbeam remained a division of Allegheny International until 1990, when Japonica Partners acquired the assets of Allegheny Corporation in Bankruptcy. Over the following several years, Japonica made incremental improvements in Sunbeam. By 1996, Japonica was ready to recoup their investment by selling Sunbeam stock to the public in an Initial Public Offering (IPO). However, before the IPO, Japonica wanted to create the most value possible in order to sell Sunbeam at the highest possible price.

In July of 1996, Japonica hired turnaround expert Albert Dunlap as the CEO of Sunbeam Corporation in hopes that Al could quickly increase the value of Sunbeam Corporation in preparation for the IPO. Unfortunately, Japonica failed to fully investigate Dunlap’s history.

Dunlap Before Sunbeam

Dunlap had a reputation as a turnaround expert. However, in each of his prior turnaround efforts he used the same slash and burn techniques, leaving greatly weakened companies with a demoralized workforce.

Dunlap became CEO of Crown-Zellerbach in 1986. He employed similar techniques, by firing 20% of the workforce and reducing the pay of the remaining employees.In 1983 Al was hired as the CEO of Lily-Tulip, a paper cup manufacturer that is today known as the Solo Cup Company. On Dunlap’s first day as CEO he fired 11 of 13 top executives. This was followed by eliminating 50% of managers and 20% of rank-and-file employees. He also ended contracts with 40% of suppliers to Lily-Tulip. The drastic cost cutting returned the company to profitability and Lily-Tulip was sold to the Sweetheart Cup Company in 1986. After the sale to Sweetheart, company sales declined dramatically.

In 1991 Dunlap began a brief stint at Australian Consolidated Press Holdings where he again reduced labor costs, sold off assets, and took the company public in 1992. After leaving ACP there were unconfirmed allegations from management that Al had manipulated the financial reports, using the same techniques he would later use at Sunbeam.

Scott Paper hired Dunlap in 1994 to turn around the company after a net loss of $280 million in 1993. Al immediately fired 11,000 workers. He then sold off most of the company’s assets before selling what little was left of the company to Kimberly Clark in 1995.

With the well-established nickname “Chainsaw Al” it was clear how Dunlap would approach his challenge at Sunbeam when he began in July 1996.

Setting the Stage for Fraud

After several years of lagging sales and profits, the primary equity holder in Sunbeam (Japonica Partners) hired Albert Dunlap as CEO of Sunbeam in July, 1996. Japonica’s intended goal was a quick turnaround and corresponding increase in stock price in order to sell the company for a greater profit. Dunlap seemed to be the person to do just that. His reputation as “Chainsaw Al” had been earned through quick turnarounds, just as Japonica was hoping for. The price of Sunbeam stock increased by 50% the day after Dunlap was hired. Clearly investors were hopeful. It should have been no surprise to anyone that Al followed a similar pattern to those at prior companies.

Al’s first day on the job was July 22, 1996. According to reports from the existing board members, Dunlap met with the board and announced that “the old Sunbeam is over” and then spent the rest of the day yelling at them. But the board members owned significant stock, so they tolerated the berating and were hopeful of further increases in the value of their stock.

Dunlap very quickly fired most of the executives, replacing them with a new management team that supported Dunlap’s approach. Of key importance, Al brought in Russell A. Kersh as the Chief Financial Officer. Kersh had been CFO for Dunlap at Lily-Tulip and Scott Paper. From experience, Dunlap knew he could rely on Kersh to make the numbers with what Al referred to as Kersh’s “ditty bag.”

With his new management team installed, Dunlap awarded 250 to 300 of the top executives, managers, and officers with significant stock options. The options had a three-year vesting period. This gave the management team a significant interest in (1) staying with the company for three years, (2) tolerating Dunlap’s abusive behavior, and (3) aiding in a rapid increase in stock price. Any manager that could meet these three criteria would gain millions of dollars through the increase in value of their stock options. If they could successfully re-position the company and take it public, they stood to make a fortune.

Cost Cutting at Sunbeam

Dunlap turned to Donald Burnett, a senior partner at the international accounting firm of Coopers & Lybrand (C&L) for help in identifying potential cost cuts. With the help of over 20 C&L consultants, Burnett proposed a restructuring plan that included eliminating 87% of Sunbeam’s products and 6,000 employees. In the end, 12,000 employees had been fired. Many departments and functions were reduced to staffing levels that made it impossible to accomplish their goals. For example, almost all of the Sunbeam information technology staff was fired and the IT functions were outsourced. The company then upgraded their IT systems, but during the upgrade the systems failed and were down for months. According to Donald Uzzi, Sunbeam’s executive vice president for worldwide consumer products, “we couldn’t bill our customers. We couldn’t keep track of our shipments. We didn’t know what we were shipping. We had customers calling day and night, asking where their orders were. Some had three orders instead of one. Others had the wrong order. Our customers were irate.” In order to get the systems running again, Sunbeam had to hire independent contractors costing much more than the laid off workers. Some of those independent contractors were the laid off Sunbeam IT workers who now had to be paid much more as independent contractors.

In another example of extreme cost-cutting, the Human Resources department was reduced from 75 employees to 17. This left Sunbeam with one-third of the HR staff of similar-sized companies.

Many factories were shut down. In some cases, retailers had ordered Sunbeam products that could no longer be manufactured, requiring that sales orders go unfilled. Some of the factories that remained open could not make product due to a shortage of components.

The Fraud Triangle

As discussed in chapter 7, the three elements of the fraud triangle are

- Incentives and pressure

- Rationalization

- Opportunity

The pressure at Sunbeam was immense. Managers were given an unreasonable target for revenues and profits, yet they were threatened if they failed to make their targets. Dixon Thayer, executive in charge of international sales was quoted as saying ”they would say, ‘I don’t care what your plan was. I don’t care what you delivered last month. We are going to task you to this number.’ Russ [Kersh] would give you a revenue and profit number and say, ‘We don’t want any bullshit. Your life depends on hitting that number.’ These numbers got to be so outrageous they were ridiculous.”

With millions of dollars at stake in stock options, managers also had great incentive for fraud.

Many managers were not aware of the fraud, but the top executives involved in the fraud had rationalized it. Based on past experience with success and rewards, Dunlap and Kersh believed their actions were acceptable. They had been hired by Sunbeam’s largest stockholder to do exactly what they had done on previous companies.

Executives and managers found opportunities for the fraud. Most of the techniques used by top executives had been used in the past by them or other executives. Yet these inappropriate activities did not go unnoticed. One of Sunbeam’s internal auditors was aware of the fraud. She attempted to address the fraud, but ultimately resigned in frustration. A stock analyst from Paine Webber named Andrew Shore noticed high inventory and accounts receivable on Sunbeam’s SEC filings. The external auditors, Arthur Andersen, in at least one case, noticed a fraud technique but dismissed it as immaterial.

Companies create systems of internal control to eliminate opportunities for fraud. However, top management typically can bypass internal controls. Also, any internal control is vulnerable to collusion, where two or more employees work together to bypass internal controls. The attitudes and culture at Sunbeam not only created the opportunity for fraud, but encouraged fraud.

The 1996 “Cookie Jar” Reserve

A “cookie jar reserve” is a technique where a company uses accounting timing techniques to shift profits from one year into a future year. This can be done by overstating liabilities and expenses, understating assets and revenues, or other techniques. Cookie jar reserves are not a valid accounting technique, are intended to mislead investors, and are not allowable by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC will fine and even pursue criminal charges against companies that use cookie jar accounting.

technique, are intended to mislead investors, and are not allowable by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The SEC will fine and even pursue criminal charges against companies that use cookie jar accounting.

Dunlap and Kersh arrived at Sunbeam in July, 1996. Using the adage to “blame your predecessor,” Sunbeam reported restructuring costs in the 1996 financial statements of $337.6 million. It is acceptable and appropriate for companies to expense restructuring costs when they occur. However, parts of the restructuring costs were inappropriate cookie jar reserves. The intent was to take what is referred to as a “big bath” to make 1996 profit appear lower than it really was, to create a cookie jar reserve, and to use that cookie jar reserve to overstate 1997 profit. At least $35 million of the total restructuring costs were improper cookie jar reserves.

By artificially lowering 1996 reported net income and inflating 1997 net income, it would appear that company profit had grown dramatically. This alone could drive up the stock price, accomplishing Dunlap’s assigned goal of turning around the company and driving up the value of stock options for insiders. However, this would be only a short-term solution. With the cookie jar reserves fully used in 1997, these reserves could not be used to inflate earnings for later years. This would cause Dunlap and Kersh much trouble later, in 1998 when the unavailability of this gimmick would actually cause profits to fall.

1997 Fraud Techniques

Although cookie jar reserves overstated the 1997 reported net income, the company wanted even higher reported profits. They engaged in additional fraudulent techniques to overstate sales and net income, including:

- Channel stuffing

- Recording supplier rebates in the wrong account

- Recording supplier rebates in the wrong accounting period

Channel stuffing

This fraud technique encourages or requires customers to buy more product than they need, which accelerated revenues for Sunbeam. This has only a short-term effect as sales are shifted to the current year from the following year. Customers will order less in future period as they use the large inventories acquired during the channel stuffing period. The channel stuffing techniques Sunbeam used included (1) early-buy incentives, (2) contingent sales, and (3) bill and hold.

Early-buy incentives

During the first quarter of 1997, Sunbeam offered customers deep discounts in order to encourage those customers to accelerate their purchases, essentially to “stock up.” This caused larger sales in the first quarter, but at the loss of sales from later periods. While inflating the first quarter’s sales and profits, in reality it only shifted those sales and profits from future quarters. This is a legal technique, but it must be disclosed to investors in the company’s financial reports. If not fully disclosed, it gives current and future investors a false impression of increasing sales. Sunbeam failed to disclose these deep discounts and accelerated sales, thereby misleading investors. Channel stuffing accelerated first quarter sales by $19.6 million but lowered sales of later quarters by a similar amount.

Contingent sales

In March of 1997, Sunbeam entered into an arrangement with a wholesale customer to create a fraudulent sale of $1.5 million. Sunbeam would ship barbecues to the customer before the quarter ended. The customer would hold the barbecues until after the quarter ended and then return them to Sunbeam. Sunbeam paid all of the shipping and storage costs. There never was a sale, only the appearance of a sale. This allowed Sunbeam to fraudulently report increased sales in the first quarter of $1.5 million and to reduce its inventory by the same amount.

Bill and Hold

During the second quarter of 1997, Sunbeam employed a “bill and hold” strategy where customers would order products before they needed them. Sunbeam would hold the products until the customer wanted delivery. This might be considered similar to a consumer “layaway” arrangement sometimes used by retailers during the holiday season, except that in Sunbeam’s case there was no up-front money required from the customer. These sales should not have been recorded until delivery to the customer. This had the effect of fraudulently boosting Sunbeam’s sales in the second quarter of 1997. In November of 1997 Sunbeam used this same strategy to sell $62 million of barbecues that would not be needed by the wholesalers and retailers until the following summer.

During the second and third quarters of 1997, Sunbeam incorrectly accounted for rebates from suppliers. It is an acceptable business practice for suppliers to offer customers rebates. Some of Sunbeam’s suppliers offered rebates to Sunbeam. The correct accounting for rebates is to recognize the rebate as a reduction of the cost of the product, essentially decreasing the expense for cost of goods sold. However, Sunbeam instead recorded the rebates as sales revenue. This had the effect of overstating revenues. Furthermore, Sunbeam recorded these transactions in the incorrect quarter. Rebates of $2.75 million which should have been recorded in later periods were inappropriately recorded in the second quarter of 1997, thus overstating revenues and net income by $2.75 million. The company used a similar technique to overstate third quarter revenues and profits by $1.9 million.

In the only inappropriate transaction detected by Arthur Andersen, Sunbeam entered into an unusual sale of parts to a company that normally serviced Sunbeam products. Andersen determined that the revenue recognition was incorrect. Sunbeam recorded revenues of $11 million from the transaction, resulting in $5 million of increased profits. Sunbeam agreed with Andersen to establish a $3 million reserve, but refused to reverse and correctly account for the transaction. Andersen was not content with this solution, but they considered transaction to be immaterial to the financial statements and still issued a “clean” unqualified opinion on the financial statements.

During the fourth quarter of 1997, Sunbeam reduced its reserve for customer returns from $6 million to $2.5 million. Reserves for returns are an offset against revenues, so reductions in reserves will increase revenues and net income. Reserves should be realistic, but Sunbeam’s were not. The reserve reductions were intended solely to fraudulently affect sales and profits. One month later, at the end of January 1998, Sunbeam further reduced the reserves to $1 million. In reality, there would soon be approximately $18 million of actual customer returns.

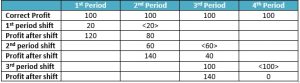

The Internal Unraveling

Time is the greatest enemy of financial statement fraud. For example, assume that a company consistently has a profit of $100 for each accounting period. In order to inflate the profit to $120 in the first period the company essentially accelerates profit from the second period. This makes the first period look terrific, but leaves the second period with only $80 in profit. In order to maintain the illusion of increasing profits, the company must accelerate even more profits from the third period back into the second period. In this example, the company now must accelerate $60 from the third period into the second, creating an illusionary $140 profit in the second period. But now the third period only has $40 of real profits and it becomes impossible to maintain the fraud.

Based on their prior experience, Dunlap and Kersh must have known this would happen. Their goal was to sell the company to a new buyer before the unraveling. The illusionary success of Sunbeam had driven the stock price so high that there were no buyers for the company. Dunlap and Kersh had become the victims of their own success.

There is not enough profit in the fourth period to shift into the third period to continue the illusion of growth. Shifting all of the profit from the fourth period will not be sufficient, and the fourth period is devastated. This type of fraud requires increasingly larger future fraud to cover up the prior fraud. The fraud shown above would unravel during the third period.

By late 1997 Dunlap and Kersh were becoming increasingly desperate to find new ways to cover the prior frauds and still show growth. There were not enough internal ways to continue the illusion. Dunlap turned to his old friend, restructuring charges and cookie-jar accounting. Having used all opportunities for Sunbeam’s restructuring charges from 1996, Sunbeam acquired three new companies in early 1998: First Alert, Coleman, and Signature Brands. It was Dunlap’s hope that these acquisitions would allow for additional excess restructuring charges and the resulting cookie jar reserves.

As the first quarter of 1998 was ending, the company still had failed to meet sales and profit targets. The company extended the closing date of the quarter by 2 days to increase sales and profits. While such an extension is permissible, it must be disclosed in required SEC filings so that investors can consider the effect on revenues and profits. However, they did not disclose this extension in their SEC filing, thus misleading analysts and investors.

A young internal auditor, Deidra DenDanto, had been noticing the problems throughout 1997 and into 1998. She questioned internal controls, issues with product returns, and bill-and-hold transactions. She found that her efforts were not effective and that management was not responsive to her concerns. She began to question the role and function of the internal audit department. There were only two people in internal audit. Her boss, Thomas Hartshorne, had been recruited by Kersh to serve at Scott Paper and now at Sunbeam. Given the relationship of Kersh and Hartshorne, it is possible to look in retrospect with concern that Hartshorne may not have been able to serve in his role with objectivity. In frustration, Deidra drafted a memo dated March 12, 1998 to executive management and to the board of directors. In her memo she commented that ”It is with much disappointment that internal audit must again bring to management’s attention the lack of prudent, ethical behavior being engaged in by this organization in order to ‘make numbers’ for the company.” She also commented that the bill-and-hold transactions were ”clearly in violation of GAAP.” Deidre took her draft memo to her supervisor, Hartshorne, who discouraged her from sending the memo. After some discussion and a conference call with Kersh, Deidre decided she would not send the memo. Had Deidra followed through with her memo she may have suffered retribution from Kersh, but may also have been a hero for uncovering and reporting the fraud.

The Public Unraveling

With all of their financial gimmicks used up, Dunlap and Kersh could no longer continue the illusion of growth, or even stability. Late in the first quarter of 1998, Sunbeam warned investors that sales had slowed. On April 3, 1998, the head of investor relations, Rich Goudis, quit without notice. Unannounced resignations of key officers are rare and raise questions among investors and analysts. Also on April 3, Paine Webber stock analyst Andrew Shore downgraded Sunbeam stock, causing the stock price to fall. Later that same day, Sunbeam issued a press release stating that sales for the first quarter would be five percent below the first quarter of 1997, one year earlier, and that the company would show a loss for the quarter. By the end of the day, the market price of Sunbeam stock had fallen by 25% and internal auditor Deidra DenDanto submitted her resignation.

On June 13th, 1998, Al Dunlap was fired by the Sunbeam board of directors. Russell Kersh was fired shortly thereafter.

The Demise of Sunbeam

The Sunbeam board hired a new CEO and management team. The Securities and Exchange Commission announced an investigation. The annual financial reports for 1996 and 1997 had to be amended to reflect the reality of Sunbeam’s financial position and results of operations. Sunbeam fired long-time auditing firm Arthur Andersen, in December of 1998 and replaced them with the firm of Deloitte & Touche.

The new management team struggled to revive the company, but was unsuccessful. The greatly-weakened company lost money in the following several years until finally filing for chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in February, 2001.

Sunbeam emerged from bankruptcy in 2002. All common stock was cancelled and the stockholders received nothing. The company, now privately owned to satisfy the creditors, changed its name to American Household, Inc. which survived briefly until being acquired by Jarden Corporation in 2005.

Although consumer products under the Sunbeam brand name are still available today, Sunbeam no longer exists as a company.

Visions of Andersen’s Future

In November, 1998, the Andersen audit partner in charge of Sunbeam’s audit ordered audit staff destroy any audit working papers for 1996 and 1997 that did not agree with the audit conclusion. The disclosure was made in a sealed deposition and went largely unnoticed. There were no significant consequences for the audit firm at the time, but a similar future action would cause the demise of Arthur Andersen.

Questions for Research and Discussion

1. Sunbeam recorded vendor rebates in the wrong account and in the wrong period.

- How would either of this affect net income?

- Please explain.

2. To what extent do you believe internal auditor Deidra DenDanto exhibited moral courage?

- If you were in the same difficult situation, how would you have handled the situation?

3. What happened to Al Dunlap?

- Research an article and summarize.

- Include a link to your article.

4. What happened to Russell Kersh?

- Research an article and summarize.

- Include a link to your article.

5. What happened to the auditing firm of Arthur Andersen as a result of their Sunbeam audits?

- Research an article and summarize.

- Include a link to your article.

6. How did the Sunbeam case affect your views and opinions of the company?

- Had you heard of Sunbeam before reading this case?

- Sunbeam is still in business today. Would you still buy products from them?