3 Establishing a Scholarly Foundation

In my opinion, effective writing has as much to do with attitude as it does with skill. You are well on your way to becoming a professional writer if you approach your writing with (a) appreciation for the intellectual work of others, (b) respect for your subject matter and audience, (c) belief in your own ability to make a contribution to the intellectual community, and (d) willingness to learn new strategies to improve your communication skills.

The foundation for scholarly work and practices of intellectual honesty is your grounding in the scholarly literature of the discipline. This involves selecting appropriate sources of information, as well using those sources ethically in your own work. If you fail to use academic sources for your paper, your paper will not be considered graduate level writing, and it will be graded accordingly. The intent of this section is to support your development of information literacy skills, so that you can effectively discern appropriate sources of information as a foundation for your writing.

3.1 Discerning Appropriate Information Sources

Establishing a strong scholarly foundation for your work is the logical partner to intellectual honesty. You may be completely transparent about the sources of information you used in your paper; however, if you have not chosen appropriate sources, then you have significantly weakened any position you take in the paper as well as the quality of your professional writing. In this subsection, I will focus in on the following, as articulated in the Faculty of Health Disciplines Transdisciplinary Program Outcomes:

Breadth & depth of knowledge. Analyze critically and systematically the breadth and depth of knowledge in the health-related academic discipline or professional practice area, including emerging trends.

Scholarly foundation. Select appropriate information sources, citing the required number, and evaluate critically the quality of current research and scholarship.

Establishing a Scientific and Scholarly Foundation

The conceptual and operational bases of the health disciplines are grounded in a shared body of scientific knowledge, which has evolved through research, clinical observation, and generation of theory. Healthcare professionals are accountable to, and reliant upon, this common body of knowledge. Graduate students build upon this knowledge base in course assignments, theses, projects, and other learning activities. It is important to ask yourself whether the sources you are relying upon in your writing are considered scholarly academic resources by others within your profession.

There are various bodies of knowledge that inform each of our perspectives, values, and decision-making processes. For example, people of various cultural and faith groups rely on a shared set of assumptions about human nature as well as values and beliefs about personal and interpersonal ways of being in the world. This body of knowledge is highly valued in the formation of their opinions. However, as healthcare practitioners, overreliance on your own cultural or spiritual ways of knowing for decision-making about client/patient well-being could result in inappropriate and unethical positions or choices, particularly if you superimpose your worldview rather than carefully attending to the worldview of the patient or client (Collins, 2018b). The body of professional knowledge in nursing, health studies, counselling, and psychology forms the common ground upon which healthcare professionals must build relationships with their clients/patients, understand client/patient perspectives and needs, and make informed decisions about client/patient health. It is also our responsibility to ensure that we apply healthcare knowledge in culturally responsive and socially just ways, as reflected in the following FHD program outcomes.

Complexity of knowledge. Acknowledge the complexity of knowledge and the potential of other worldviews, interpretations, ways of knowing, and disciplines to contribute to knowledge.

Cognitive complexity. Be tolerant of ambiguity, and cultivate cognitive complexity to enable you to see beyond your own values, worldview, and sociocultural contexts.

Integrating Sufficient Sources

Some graduate programs specify the minimum number of scholarly sources that you must integrate into a particular writing assignment. See the example from the Master of Counselling at Athabasca University (AU) in Figure 3.1.1 below. In other cases, you will need to use your own judgment to ensure you sufficiently ground your paper in the professional literature.

Figure 3.1.1

Master of Counselling Scholarly Foundation in Writing Expectations

Unless different instructions are provided in the assignment description, all Graduate Centre for Applied Psychology (GCAP) course papers are expected meet the following minimum standards:

- The reference list must include recent scholarly (typically peer-reviewed) sources such as academic journals, books, monographs, and other appropriate sources. GCAP defines recent as within the last ten years, with emphasis on the most current sources.

- A shorter paper (i.e., 10–12 pages*) must include at least 10 recent peer-reviewed sources.

- A longer paper (i.e., 15–20 pages) must include at least 15 recent peer-reviewed sources.

*Note: Page lengths refer to the assignment criteria, not the length of paper you choose to submit!

- Students are encouraged to draw on the course materials and required/supplementary readings in assignments, although these sources do not count toward the minimum research requirements outlined above.

- Citations of foundational or important critical works may reference sources older than ten years.

- No citations from secondary sources should be used unless the original work is not available from the AU library.

- Such exceptional secondary sources should be kept to a maximum of one or two citations.

Students who do not meet the minimum standards for grounding their arguments within the academic literature of the discipline will receive an automatic grade deduction.

If you are writing on a topic with little current literature, you must consult, in advance, with the course instructor for approval to rely on older peer-reviewed sources in your paper.

One of the typical features of quality healthcare literature is that it is peer-reviewed. This means that other professionals with relevant expertise have provided feedback on the content and judged its quality as sufficiently rigorous and scholarly to warrant publication. Many books are not peer-reviewed. However, most academic journals are peer-reviewed. The Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy (n.d.), guidelines state:

The purpose of submitting manuscripts for blind review is threefold: to benefit from the reviewer’s expertise in a particular field of study or practice, to gain the reviewer’s critical assessment, and finally, to provide concrete feedback to the authors. The intent of the review process is not only to assist the editors in making decisions about manuscripts for publication, but also to educate authors as to how to improve or strengthen their professional writing” (Peer Review Process section, para. 1).

In this age of digital publishing, with its ease of self-publishing, there are also many resources that are not peer-reviewed. This does not necessarily mean they are not good quality, scholarly sources. It means simply that you must apply your own critical lens in evaluating their appropriateness for integration into your graduate papers. This webpage, for example, has not undergone a formal peer review; however, it is based on several decade’s worth of interaction with graduate students, instructors, faculty, editors, and available writing resources and guidelines.

3.2 Enhancing Information Literacy

Information literacy is the ability to identify, evaluate the appropriateness of, and effectively make use of, information for a particular purpose. The Association of College and Research Libraries (2016) defined information literacy as follows: “Information literacy is the set of integrated abilities encompassing the reflective discovery of information, the understanding of how information is produced and valued, and the use of information in creating new knowledge and participating ethically in communities of learning” (p. 8).

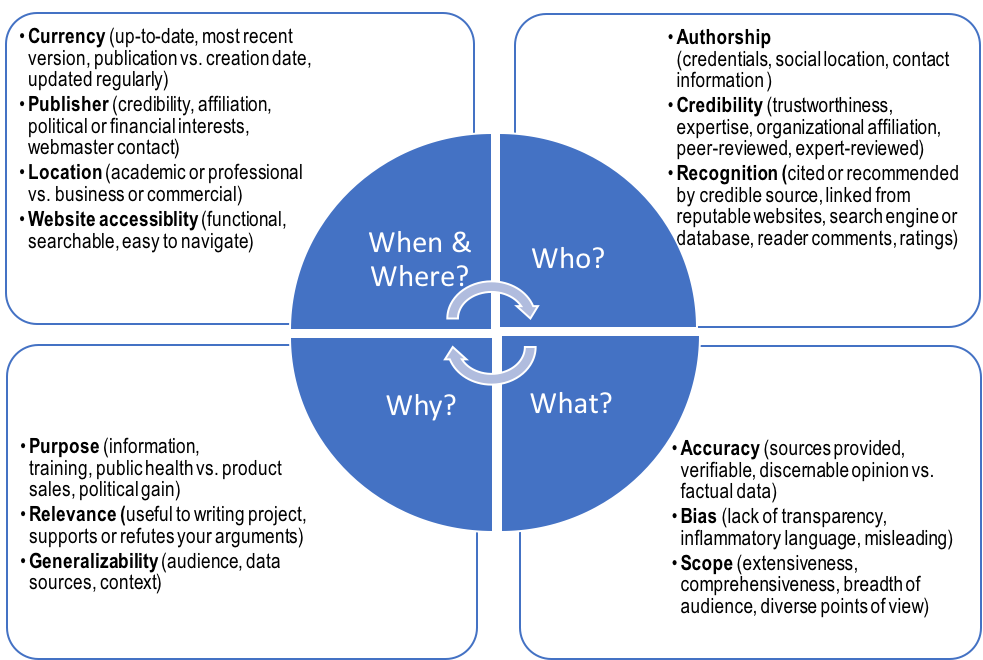

Operating with scholarly integrity requires you to select appropriate sources from which to draw information and then to identify accurately and communicate the information or argument from your source. If you argue, for example, that the sky is falling in a scholarly paper, you may be accurately reflecting the assertion of Chicken Little (from Robert Chamber’s folk story reprinted in Fowle [1956]); however, you would be hard-pressed to convince your instructor that Chicken Little is a reliable and credible source. How then do you go about selecting sources of information that are considered sufficiently scholarly? Consider the diagram in Figure 3.2.1 below; it synthesizes some important considerations for selecting information sources. The sources I drew on to create Figure 3.2.1. are integrated into Exercise 3.2.1 (below).

Figure 3.2.1

The Process of Professional Writing

| Click on the audio file on the left, or access the alternate text for the figure if you prefer an audio description. |

Exercise 3.2.1

You may want to explore some of the sources below to enhance your understanding of information literacy and to establish your own criteria for choosing appropriate sources.

-

Athabasca University. (2019). Evaluating Internet sources. https://libguides.athabascau.ca/c.php?g=696575&p=5192351

-

Athabasca University. (2019). Internet searching: Evaluating web information. https://libguides.athabascau.ca/c.php?g=696575&p=5192351

-

Athabasca University. (2019). FGS: Digital literacy repository https://drr2.lib.athabascau.ca/course/51197

-

Athabasca University. (2019). Peer review: What is peer review? https://libguides.athabascau.ca/peer_review

-

Cornell University. (2019). Distinguishing scholarly from non-scholarly periodicals: A Checklist of Criteria: Introduction. http://guides.library.cornell.edu/c.php?g=31867&p=201758

-

Cornell University. (2016). Evaluating web pages: Questions to consider: Categories. http://guides.library.cornell.edu/evaluating_Web_pages

-

Society of College, National, and University Libraries. (n.d.). 7 pillars of information literacy through a digital literacy ‘lens.’ http://www.sconul.ac.uk/sites/default/files/documents/SCONUL%20digital_literacy_lens_v4_0.doc

-

University of California. (2019). Evaluating web pages: Techniques to apply & questions to ask. http://guides.lib.berkeley.edu/evaluating-resources

-

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2015). MedlinePlus guide to healthy web surfing. https://medlineplus.gov/healthywebsurfing.html

In the next subsection, I will review the main categories of information sources to provide guidance on applying the best principles of information literacy to these sources.

3.3 Selecting Information Sources

Library Sources

The most obvious starting place for finding scholarly information is the AU library. You are strongly advised to draw most of your sources from the library. The library journal collections have been carefully screened and selected for quality and relevance. The librarians have created a number of resources to help you optimize your use of the library. If you are an AU student, check out the Quick Links on the main page of the AU Library.

In graduate papers, a heavy emphasis is placed on peer-reviewed and current scholarly sources. You must also be discerning when it comes to books and other monographs. If you are unsure about a source, apply the principles in Section 3.2 Enhancing Information Literacy. The library may contain self-help books, for example, which likely will not meet the criteria for inclusion as scholarly sources in your academic papers within the health disciplines.

Web Sources

At times, it may be appropriate to include carefully selected information from the web in your assignments. There are some great sources of information on the Internet, and there are some very biased and nonscholarly sources. Your responsibility, as a scholar, is to distinguish between the two. In particular, you may want to attend to the following relatively reliable information sources:

- Open access (i.e., freely available on the Internet) journals that are relevant to the health disciplines. The International Journal of Collaborative Practices, the MedEd PORTAL: The Journal of Teaching and Learning Resources, and the Qualitative Report are examples. Many journals are moving to open access to increase the accessibility of knowledge. However, the quality and credibility of these sources varies. So, be sure to read critically both the content of the article and the description of the journal. The AU library’s list of Open Access Resources allows you to search journals, thesis databases, e-books, and other repositories.

- Professional associations can be valuable sources of information on ethics, standards, guidelines, and protocols. Check out, for example, the Canadian Nurses Association, the Nurse Practitioner Association of Canada, the American Psychological Association, the Canadian Psychological Association, or the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

- Special interest groups, community organizations, or government sites can also offer current, well-researched, and credible documentation on current issues and trends, government policies, theoretical approaches, interventions, as well as other issues. Consider, for example, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Mental Health Association, Statistics Canada, or the Dulwich Centre websites.

There are many other independent webpages designed by individuals or groups with a range in credibility as scholarly sources. You must be careful to apply a critical lens to evaluate both the content and the source of the information. Unless you find a peer-reviewed article online or your assignment specifically permits the use of Internet sources that have not been peer-reviewed, these sources should be in addition to the minimum requirements for a scholarly foundation of your paper (See Figure 3.1.1 in Section 3.1 Discerning Appropriate Information Sources). The Society of College, National, and University Libraries (SCONUL) provides a very useful competency summary for moving from identifying digital sources through to integrating those resources into your paper: 7 Pillars of Information Literacy through a Digital Literacy ‘Lens.’

Open Educational Resources

In recent years, there has also been an evolving body of knowledge that is shared publicly through open educational resources (OERs). These are materials that are freely available on the Internet and have been specifically designated for sharing, adapting, and repurposing by others. These resources are often grounded in a social justice approach to knowledge that asserts the rights of all people and peoples to have access to credible knowledge and high-quality learning opportunities. However, you must be diligent in critically analyzing these sources for use in professional writing projects. They must meet all of the information literacy criteria for scholarly resources. Wikipedia is a good example of an OER that would fail to meet information literacy criteria for academic or professional writing, because there is no way to trace and validate the sources of any specific content it contains. On the other hand, the OpenLearn Project (available through the UK Open University) offers materials that would meet most of these scholarly standards.

Along with written materials, you can access open source images, videos, and other digital materials. It is important to review carefully the copyright certificates for these materials to ensure you use and credit them appropriately. Many OERs have a Creative Commons (CC) copyright license, which allows others to adapt, choose, rework and evolve portions, or the whole of particular materials for new purposes. Some restrictions may apply depending on the type of CC license. For example, this writing resource has a CC license that requires others to acknowledge my authorship, to license their work in a similar way, and to agree not to use the content for commercial purposes. The intent of this type of copyright is to support collaborative knowledge sharing and development. If you are looking for an image to include in a course assignment, you are best off searching for OERs; otherwise, you may be required to get permission from the copyright holder to reproduce the image. A common scholarly integrity infraction, for example, is the inclusion of commercial comics in PowerPoint presentations. Rarely have presenters obtained permission from the copyright owner.

Exercise 3.3.1

Check out the following examples of sources of OERs. Search for an OER on a topic of interest to professional practice in the health disciplines.

-

Commonwealth of Learning. (2019). OAsis, COL’s Open Access Repository. https://www.col.org/programmes/open-educational-resources

-

Creative Commons. (n.d.). CC Search. https://search.creativecommons.org/

-

OER Commons. (2019). Explore. Create. Collaborate. https://www.oercommons.org/

-

Open Education Consortium. (2019). Open Educational Resources. https://www.oeconsortium.org/courses/search/

The bottom line in selecting sources for academic papers, presentations, or other scholarly works is that you must apply a critical lens to the choices you make. If you write a brilliant paper based on unscholarly or biased sources, your paper will have little academic value, which translates into a low grade. Your choice of sources forms the foundation for all that follows: your argument and your grade!

Sources to Use with Caution

There are a few sources of information that you should use with caution in your graduate papers.

- Abstracts. In many library databases, you are able to access the abstracts for various journal articles. There may be a temptation to rely on the information in the abstract to support the points you want to make, rather than take the time to retrieve the article. However, you are expected to read the actual article before you draw on the author’s ideas. If you are unable to access the entire article, then consider finding a different source for your information. On the very rare occasions that you have no other choice but to cite content from an abstract, be sure to indicate clearly that you accessed an abstract not the full article.

- Personal communication. Personal communication refers to any information that you have obtained, either verbally or in writing, that is not publicly documented or retrievable. This includes conversations with your instructor, email correspondence, statements made in supervision or consultation contexts, or comments from an expert with whom you correspond. In most cases, ideas expressed in this context are likely supportable through the literature base. You are expected to turn to those publicly available academic sources. There are less common experiences, however, when such a source presents an idea that is innovative or stated in a particularly eloquent manner. In these cases, carefully cite your source in APA format. Online discussion posts from your graduate courses are not considered personal communication; rather, they should be treated as online forum posts. These are rarely appropriate sources for academic papers.

3.4 Padding Your Reference List

Many graduate assignments outline the number and type of academic sources that you are required to use. In addition, you are expected to use each source in a substantive way, which means that you draw ideas that make a significant contribution to the arguments in your paper from each source you list in your references.

The following activities are considered cheating and constitute a breach of scholarly integrity:

- You pad your reference list by adding references that you did not actually use to write the paper. You must have read every article in your reference list. As well, each source in your reference list must correspond to a citation within the body of your paper.

- You add a citation from which you have not drawn substantive content. For example, you have used Jerry (2019) and Nuttgens (2018) for the key points in a paragraph. However, you need one more source to meet the standards for creating a sufficiently scholarly foundation in your writing, so you find an article on a similar topic that adds nothing new; you skim the article, and add it to your citation list (Jerry, 2019; Nuttgens, 2018; Padding, 2020).

Each source you use should clearly contribute something unique to your paper. When you engage in the above activities to pad your reference list, your paper is no different than it was before you added these new citations and references. Instead, if you find yourself short a couple of sources by the time you get to the end of your paper, ask yourself the following questions:

- Which ideas have I not fully addressed?

- Which arguments, counterarguments, or issues could I be missing?

- Which key points could benefit from further support?

- Which differing voices could I include to provide alternative perspectives to the points I have made?

In other words, think critically about your paper; think critically about the sources that you are using; and integrate them in a way that is meaningful and makes a substantive contribution to the flow of argument in both your paper and your field of interest.