4 Developing a Writing Plan: Critical Deconstruction

Planning your paper involves selecting a topic, carefully reviewing the assignment criteria to determine the objective of the paper, and delving into the professional literature to start gathering and organizing your research material in a meaningful way. In this section, I introduce principles and practices to enhance the strength and congruence of your writing plan by deconstructing (i.e., pulling apart) both the assignment expectations and the current professional literature. Some students make the mistake of thinking that these processes are sufficient for professional writing. However, they are simply the background research for your paper! In the Chapter 5, you will learn how to draw on this background research to infuse your own voice into your professional writing.

4.1 Selecting a Topic

Choosing Your Topic

In most cases when you are writing a graduate paper, the place to start is with the description provided for the particular assignment. It is possible to write an amazing paper, but not address the topic or objective targeted in the assignment or to place too much emphasis on one element at the expense of others. As a starting point for examining this issue, please read the excerpts from two assignment descriptions in Figure 4.1.1 below.

Figure 4.1.1

Sample Assignment Descriptions

Assignment 1

The objective of this assignment is to give you an opportunity to analyze critically, and to deconstruct, the major tenets of psychotherapy models by engaging in a process of case conceptualization. Drawing on one of the case scenarios provided, shape your analysis through the following questions:

- What is your working hypothesis about the problem? Provide a brief analysis of the problem from the perspective of your chosen model. Draw on the model’s concepts for understanding the nature of humans, the nature of healthy (or well-adjusted) functioning, and the causes of problems (i.e., not functioning in a healthy manner).

- What is your working hypothesis about how change is likely to occur? Based on your chosen model, elaborate on the nature of change. You may want to take into account which variables or factors are targeted, which processes are involved, whether change occurs within, or outside of, the counselling session, and the model’s perspectives on the role(s) of client and counsellor.

- What intervention might you choose? Identify a potential intervention based on your chosen model. Describe what you would do to be helpful to the client, what you would invite the client to do, what resources you would draw on, the context of your activities, and so on.

- What outcomes do you anticipate? How would you describe a successful outcome for the client based on your chosen model. Be specific and creative in imagining a preferred future for this client.

Assignment 2

We live in a society in which there is differential privilege, inequitable access to health resources and services, and lack of full participation in community, organizational, and social systems, based on both visible and invisible cultural identity factors and group affiliations. The objective of this assignment is to (a) identify the types of messages that abound in popular media that either challenge or perpetuate oppression of members of nondominant populations, and (b) articulate a reasoned, supported, and convincing argument in support of equity, cultural sensitivity, and social justice in health service provision. Your task is to write an article that could be published in a popular magazine or newspaper.

- Choose a topic or issue related to culture or social justice (impacting one or more nondominant populations). Then, scan the popular media to see what ideas are currently being discussed, or which diverse positions are being argued. You can do this through news reports, magazine articles, websites providing commentaries, or other appropriate sources. Try to use online sources so your peers can easily access your sources.

- Analyze critically the various messages you encounter. Once you are satisfied that you understand the arguments being made, write a brief paragraph (4–6 lines) in which you synthesize the essence of the debate, challenge, or controversy that has captured your attention. Select 2–3 articles to reference, and provide links to them.

- Decide on a position you want to take on the topic or issue. Draw from the values, principles, or competencies outlined in the course. Articulate a clear thesis statement that will form the foundation for your own article. This can be a rebuttal to one or more of the original articles, or it can further extend their positions.

- Develop the key points in your argument. Base your points on your thesis statement, and integrate and synthesize the professional literature to support your position. Come up with a catchy title for your article to encourage others to read it. Be creative about the message you want to send.

There is a lot of important information provided in these assignment outlines that will help you begin your writing process. In both cases, you must start by selecting a topic (i.e., the psychotherapy model or the topic/issue related to culture and social justice). Figure 4.1.2 provides a few tips for selecting a topic.

Figure 4.1.2

Tips for Selecting a Topic

- Flexibility. Your topic may evolve as you delve into the professional literature. Do not lock yourself in too tightly at the outset.

- Breadth. It is better to cast a wide net to ensure you have sufficient research to allow you to understand the topic as fully as possible before narrowing your focus. It will not be acceptable to say, “No one has written in this area!”

- Relevance. Your topic should be grounded in the existing literature within the field of health disciplines. You may be very interested in the effects of owning pets on climate change; however, you may have difficulty creating a thesis and argument that position this topic within health disciplines’ research and practice.

- Cultural responsivity. Many topics in the health disciplines require attention to culture and social justice. Consider the risks of applying ethnocentric lenses, engaging in cultural appropriation or exploitation, or excluding diverse voices in your choice of topics; take appropriate steps to avoid these risks.

Adapted from “Literature review and focusing the research” in Research and evaluation in education and psychology by D. M. Mertens, 2015, p. 93–96.

Clarifying Your Objective

Before you can begin writing about a particular topic, you must understand clearly the objective of the assignment. The objective might be to describe a particular phenomenon, to argue a specific point of view, to reflect critically on personal values, to increase self-awareness, or to persuade the reader to adopt a particular position. Understanding the objective of your writing is a key step in planning your paper.

A well-worded assignment description uses language that is consistent with the objective of the assignment. Many course designers draw on Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of learning objectives as a means of providing guidance to students about the academic objective(s) of the assignment (i.e., the purpose or aim of the learning activity and assessment process). Bloom identified three domains of learning that assignments can target: cognitive, affective, and skills.

- Cognitive learning is demonstrated by recalling knowledge; comprehending academic and professional materials; organizing information; analyzing, applying, and synthesizing knowledge; and evaluating critically various ideas. The cognitive domain is often assessed through activities such as: (a) contributions to online discussions, (b) exercises and activities completed as part of the learning processes, (c) papers and other major course assignments, and (d) quizzes and exams. In any given course, each of these components may target different levels of cognitive learning.

- Affective learning takes into account emotions, attitudes, beliefs, preferences, worldviews, and values. Affective learning is demonstrated through attitudes of awareness, interest, self-reflection, and personal responsibility in academic and professional situations, as well as through the ability to demonstrate the attitudinal characteristics or values commonly espoused as appropriate to the academic, professional, or applied practice of health disciplines. Although affective learning can also be reflected in other components of each course, it is often targeted through particular class discussions, self-reflection exercises, and personal position papers.

- The final domain focuses on skills development. The original work by Bloom (1956) centred on basic psychomotor skills. In the context of graduate education in the health disciplines, the skills targeted are more complex interpersonal and applied practice skills. You may be asked to demonstrate your skill development in a number of ways: online or in-person learning activities, taped or live involvement with patients/clients as part of supervised practica, and video or audio demonstrations in skill development courses.

Each domain is broken down into specific types of learning goals and descriptors that are used to assess whether those goals have been reached. I have adapted Bloom’s (1956) descriptors in Table 4.1.1.

Table 4.1.1

Bloom’s (1956) Taxonomy of Education Objectives

|

Cognitive Domain |

|

|

Level of Learning |

Descriptors |

| Knowledge |

|

| Comprehension |

|

| Application |

|

| Analysis |

|

| Synthesis |

|

| Evaluation |

|

|

Affective Domain |

|

|

Level of Learning |

Descriptors |

| Awareness |

|

| Commitment |

|

|

Skills Domain |

|

|

Level of Learning |

Descriptors |

| Simulated demonstration |

|

| Generalization |

|

| Responsive implementation |

|

Exercise 4.1.1

Review the two sample assignments in Figure 4.1.1 (above), and identify words that suggest the levels of learning targeted in the assignment.

For most graduate papers, you will be required to go beyond knowledge and comprehension to analyze and apply what you have learned (see Figure 4.1.1, Assignment 1 above), to engage in evaluation, and to integrate and synthesize the relevant literature (see Figure 4.1.1, Assignment 2 above). If the level of learning is unclear from the assignment description, assume you are to aim for the highest levels of learning. Both of the assignments in Figure 4.1.1 focus predominantly on the cognitive domain. In other assignments you may be expected to demonstrate a commitment to the values of the profession (affective domain) or to engage in applied practice activities (skills domain) in a way that is responsive to patient/client needs and contexts. Some course assignments may be more open-ended, offering you a chance to design your own writing plans to meet particular learning objectives.

Applying the levels of learning to your analysis of the assignment gives you clues about how to establish an appropriate objective for your paper. Table 4.1.2 illustrates both a congruence and a mismatch between levels of learning and the objective identified for an assignment. In each case, the topic is models of patient/client care.

Table 4.1.2

Congruence Between Level of Learning and Writing Objective

|

Level of learning |

Congruent Objective |

Mismatched Objective |

| Analysis | The objective of this paper is to analyze critically the similarities and differences between an individualist and an ecological approach to patient/client care. | The objective of this paper is to describe two different approaches to health care: individualistic and ecological. |

| Synthesis and evaluation | The objective of this paper is to build a solid case for an ecological approach to patient/client care based on current theory and clinical research. | The objective of this paper is to identify and create a list of the best practices for patient/client care. |

| Commitment | The objective of this paper is to reflect on and position my values and beliefs about how best to care for each unique individual patient/client I encounter. | The objective of this paper is to explore what I believe about patient/client services and to identify my personal values. |

Exercise 4.1.2

Recall an assignment you have recently written, or choose one from a current course. Complete Exercise 4.1.2 to practice crafting objectives that reflect cognitive levels of learning. There are no right answers to this exercise, because many different objectives could emerge from a single topic.

What is important is that you identify an objective that reflects the levels of learning targeted by the assignment, before you start conducting research into the topic area. Depending on your knowledge of the topic area, you may begin with a relatively simple objective and elaborate it over time as you increase your knowledge base. Your objective can be incorporated directly into the introduction of your paper.

4.2 Understanding Literature Reviews

One specific type of professional writing you will encounter in your graduate program is a literature review. The term literature review is used in many different ways. It is important to clarify what this term means in various contexts, so that you can discern the type of literature review that is appropriate for various academic and professional writing activities.

In many course assignments, you will critically analyze the professional literature with a view to synthesizing and integrating it in support of the specific objective of the assignment (e.g., application of theory to practice, analysis of a case study, critical analysis of approach or model). In other cases, the core objective of the assignment, or a substantive portion of it, will be to conduct a literature review (i.e., an in-depth analysis of a particular topic, theory, concept, methodology, argument) based on the professional literature.

Exercise 4.2.1

Compare and contrast the diverse types of literature reviews described in the following resources. Different labels are sometimes applied, so pay close attention to the purpose and content of the various types of reviews.

-

University of British Columbia Library. (2019). Introduction to literature reviews. http://guides.library.ubc.ca/litreviews

-

University of Southern California Libraries. (2019). How to conduct a literature review: Types of literature reviews. http://guides.lib.ua.edu/c.php?g=39963&p=253698

-

University of Toledo University Libraries. (2016). Types of literature reviews. http://libguides.utoledo.edu/c.php?g=284354&p=1893889

-

Western University Libraries. (2017). Introduction to different types of literature reviews. https://www.lib.uwo.ca/tutorials/typesofliteraturereviews/

In Figure 4.2.1, I summarize the various types of literature reviews based on the objective (purpose) and common applications of each type. As you are conducting your own research in your topic area, try to classify literature reviews you encounter according to these two criteria.

Figure 4.2.1

Types of Literature Reviews

| Type of Review | Objective | Common Applications |

| Traditional review, Narrative review | Critique existing literature to generate a narrative synthesis of themes related to a particular topic, sometimes pointing to new research possibilities |

|

| Theoretical review | Analyze critically theoretical models or concepts with a view to identifying places where existing theory fails to address new problems or contexts |

|

| Conceptual review | Highlight what is known about a particular concept and potentially point to new understandings or applications |

|

| Historical review

State-of-the-Art review |

Track the evolution of a theme, concept, model, or phenomenon over time, or review only the most current literature |

|

| Methodological review | Critique the methods and techniques used in conducting research rather than research outcomes |

|

| Argumentative review | Synthesize and integrate the literature to further support or to counter-argue an existing thesis and argument in the professional literature |

|

| Critical review | Analyze critically the literature, critically evaluating diverse perspectives, to support conceptual innovation or theory generation |

|

| Systematic review | Analyze systematically, comprehensively, and rigorously the quality and quantity of existing research through predefined parameters to answer specific questions |

|

| Meta-analysis or metasynthesis | Analyze statistically the results of various quantitative studies or systematic analysis of themes or concepts across qualitative studies to draw cross-study conclusions |

|

| Scoping review, Integrative review | Identify and categorize themes from a comprehensive analysis of all available literature in a particular area, without specific analysis of the quality of the studies |

|

Note. Adapted from “Introduction to literature reviews,” by University of British Columbia Library, 2019 (http://guides.library.ubc.ca/litreviews); How to conduct a literature review: Types of literature reviews,” by University of Southern Californian Libraries, 2019 (http://guides.lib.ua.edu/c.php?g=39963&p=253698); “Types of literature reviews,” by University of Toledo University Libraries, 2019 (http://libguides.utoledo.edu/c.php?g=284354&p=1893889); and “Introduction to different types of literature reviews,” Western University Libraries, 2019 (https://www.lib.uwo.ca/tutorials/typesofliteraturereviews/).

Moving down the list in Figure 4.2.1, the types of reviews become more systematic, rigorous, and comprehensive. Critical reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, metasyntheses, scoping, and integrative reviews are most often used as thesis research studies or elements of larger research projects; these reviews could then be published as journal articles. These are typically too time-consuming and demanding for course assignments.

Methodological reviews are commonly proposed in research methods texts, where the focus is on critical evaluation of the methodology, rather than the outcomes, of various studies. In some cases, these also form a foundation for research proposals, where the focus is more specifically on research methodology.

Mostly commonly, you will encounter course assignments that require traditional/narrative, theoretical, conceptual, and sometimes historical or state-of-the-art reviews. These types of reviews are not necessarily mutually exclusive; you may integrate elements of several within one literature review depending on the topic you select. In addition, they all have several things in common:

- They do not require a comprehensive review of all available literature.

- They focus on the themes, concepts, or ideas in the existing literature, rather than a specific analysis of the quality of the literature (although it is still important to select credible sources and to be mindful of the quality of research you are reading).

- They incorporate qualitative and quantitative research studies as well as other literature reviews or theoretical/conceptual articles.

- Their objectives reflect higher order levels of learning (i.e., analysis, synthesis, evaluation).

- They can be organized in a way that articulates and supports a new thesis and set of arguments about the topic.

- They can be positioned either to lead logically to questions for further research, or to present implications and conclusions based on the current professional literature.

Depending on the nature of the assignment, you may be required to draw on a specific range of sources from the professional literature. These types of literature reviews also can be used to form a foundation for your thesis research proposal and later become a chapter in your thesis or a manuscript for publication. If you choose the course-based exit route, you may develop a journal article drawing on one or more of these types of literature reviews. In each case, you should clearly state both the topic and the objective of your review in a way that communicates both the levels of learning targeted and the scope and nature of your review. You can use the other types of literature reviews as resources for writing your own paper. Some of these (e.g., critical reviews, systematic reviews, meta-analyses) provide excellent overviews of a research topic.

4.3 Deconstructing the Professional Literature

Now that you have a topic and an objective for your professional writing, it is time to begin to gather and analyze appropriate sources. As noted in Chapter 3 Establishing a Scholarly Foundation, most graduate writing requires you to draw on peer-reviewed journal articles as your primary sources of information. At this point, you will engage in a process of deconstruction that involves dismantling or breaking something apart the better to understand it. This process of deconstruction is an important first step in writing a graduate level literature review, but it is just the first step! The questions below support deconstruction of the professional literature:

- What are the key points from each article that are relevant to your topic and objective?

- What is the audience, context, and objective within which these ideas are presented?

- What is the sociocultural landscape in which these ideas are grounded?

- What are the underlying assumptions of the authors, including any potential biases?

- What are the origins of these ideas or assumptions?

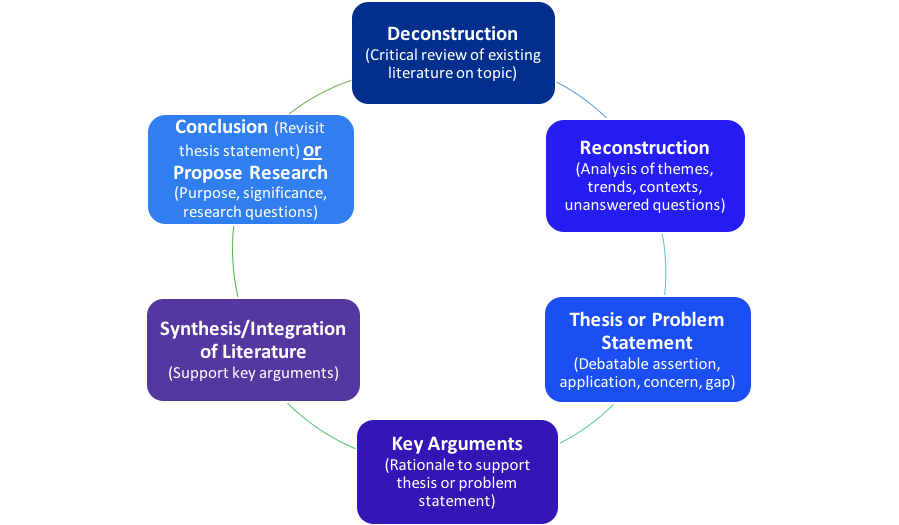

There is no single, correct way to write a literature review or to engage other forms of professional writing. Frequently, writing is a recursive process wherein you review the literature; organize the literature; identify core ideas or themes; then go back to the literature; and subsequently, revise themes, ideas, and sometimes even topics! Figure 4.3.1 (below) provides a visual representation of the professional writing process that emphasizes its recursive nature. You explore the literature and come up with what you think is a solid thesis and argument for your paper (addressed in Chapter 5); then later, you find an article that causes you to shift your perspective, which impels you to modify your thesis and arguments. You can systematically follow the diagram below in a clockwise fashion, or you can discover that it works better for you to work back and forth between all of the steps in a nonlinear way.

Figure 4.3.1

The Process of Professional Writing

| Click on the audio file on the left, or access the alternate text for the figure if you prefer an audio description. |

The process of deconstruction may appear less significant in this diagram than the remaining processes (addressed in Chapter 5), because deconstruction reflects only 1/6 of the content. However, you cannot really begin to write a graduate paper until you fully appreciate the professional context of the topic about which you want to write. There are a number of important skills involved in generating and organizing the ideas that you draw from the professional literature; and then reading, thinking, and writing critically about them. These skills and processes will be addressed in the following subsections.

4.4 Generating and Organizing Your Ideas

There are many techniques for starting to develop the content of your paper. Here are two suggestions:

- If you already know something about the topic, start by writing down all the points you would like to integrate into your paper. See what themes emerge and what areas you might need to explore further. Then turn to the professional literature to either confirm or redirect your thinking.

- If the topic is relatively new, then read, read, read. Start with more general information to establish a knowledge foundation, and then look for critiques, analyses, or other issue-focused articles about the topic. See if others have written papers with a similar objective to your own tentative objective. Be sure to take notes on all the points that seem relevant to your paper.

Making Meaning of the Professional Literature

Before the days of computers, many graduate students gathered their notes on slips of paper and then arranged and re-arranged them on their desk until they had a clear sense of the meaning of the literature they were reading. You may still find this a useful activity. However, it is very easy to use a Microsoft Word file to arrange your ideas on particular topic. While I was creating the original content upon which this resource has been built, I was working on a theoretical/conceptual literature review in the area of social justice and career practice. I have used this review (below) to demonstrate how I organized information as I read and reflected critically on the academic body of knowledge in this area. This is just one way to organize and keep track of ideas from various sources as you conduct your initial research on a topic. It is organized into three days, during which I continued to read the literature and to add to my research summary.

My Background Research: Day 1

Additional Tips

- Add titles and subtitles as you go to help you keep the material organized.

- Be sure to paraphrase the material you read, and to indicate when there is an exact quotation. If you do not do this carefully now, it will be much harder later to go back and make sure you are not plagiarizing the original source.

- Add each reference to your list as you go. You can worry about final formatting later.

My Background Research: Day 2

Sections 1 and 2 of my notes remained the same at this point, but I added in some new ideas under two new themes below.

Click here for an accessible PDF version of these images.

Additional Tips

- You do not have to wait until you find a point in an article to start adding in headings and key points. You will notice I started two new sections, because I already had an idea of where I want to head with the paper. I then began to look for supporting points in the literature as I continued to read.

- Make sure you add in the references from the original sources you use.

- Remember, if you plan your research and writing process well, you can begin to build the literature review for your thesis or course-based exit project by writing about similar themes in different courses. You cannot copy material directly from one paper to another, but if you create this type of summary of the literature, you can draw on the same ideas and resources in your summary to support a new thesis and arguments.

My Background Research: Day 3

I did not make any changes to Section 1 the next time I sat down to add to my background research; however, I added content to other sections and created a couple of new categories or themes.

Click here for an accessible PDF version of these images.

Additional Tips

- I started out looking for some specific information on social justice definitions. But I still read through each article thoroughly to identify the points I thought were important. That way, I did not have to return to an article multiple times looking for different information.

- For the articles mentioned elsewhere that I had not yet read myself, I added their pertinent information to the reference list, but kept it separate until I did read them and was able to decide if I want to include their points or not. That way, I had a path to follow to spread my research net wider, and I preserved myself from relying on secondary sources.

- I attached citations to every point I made so that if I re-arranged these points in my final paper, I still was able to keep track of the sources of each idea.

Optimizing Your Time Investment

When I find a topic area that interests me, I often start by creating a document like the one in the previous subsection that covers more content than I will use in any given paper. The final paper will not necessarily follow this structure, but I will have, at my fingertips, the information to support the key points and subpoints I select for each paper. Notice that the way in which I have pulled together this information reflects higher order learning objectives. For example, I did not simply list one point from one source; instead, I synthesized and integrated ideas across sources as I read and make notes as I demonstrate below. Notice that I have put in red any citation that I have not yet read fully in the original, so that I do not inadvertently include them in a final document before reading them.

The shifting demographics of Canadian society and increased systemic barriers to career and life success (Arthur & Collins, 2005b) are bringing social justice back to the forefront (Arthur & Collins, 2005a; Fouad et al., 2006), particularly in the area of career development (Toporek & Chope, 2006).

I am also evaluating the literature:

Attention to social class is highlighted in the literature (Blustein et al., 2005; Liu & Ali, 2005). It is important to understand the way in which social class forms a cultural schemata that impacts career development values, beliefs, assumptions, aspirations, and goals (Blustein et al., 2005; Liu & Ali, 2005).

The intellectually challenging climate and the opportunity to articulate and debate ideas with other people were the things I found most exciting about graduate school. I still seek out opportunities to work collaboratively with my colleagues on projects that will push me to think critically, creatively, and beyond my current points of view. This often creates a synergy that results in new ideas and directions I might not have generated on my own.

I hope that you will have many opportunities throughout your graduate program to engage in this type of co-constructive learning process. Engaging with the professional literature as you write your graduate papers offers you a similar opportunity, if you approach it with a critical mindset. You bring your ideas, worldview, and expertise to create an interactive process that can result in exciting new perspectives. I hope that you will welcome this challenge, as I do.

4.5 Reading, Thinking, and Writing Critically

Thinking About Your Thinking

Throughout your graduate program, you will be expected to explore alternatives with an open mind, and then establish a personal position on certain issues, supporting your points of view with various forms of evidence, theory, or plausible lines of reasoning that will stand up under the healthy review and scrutiny of your classmates and instructors. You will be asked to respond to your instructors and peers from a place of curiosity and scepticism, key components of a scholarly attitude. You must develop the ability to read, think, and write critically, which is reflected in the following Faculty of Health Disciplines (FHD) Program Outcomes.

Breadth & depth of knowledge. Analyze critically and systematically the breadth and depth of knowledge in the health-related academic discipline or professional practice area, including emerging trends.

Critical analysis. Demonstrate critical reading, thinking, and writing.

Generalization of knowledge. Analyze critically, apply, and generalize knowledge to new questions, problems, or contexts.

If these expectations are new for you, welcome the challenge and the excitement of academic thought and discussion. Each invites you into a process of thinking about your thinking.

Exercise 4.5.1

Take a moment to write your own personal definition of critical thinking. Then review the definition(s) of critical thinking on the Foundation for Critical Thinking website. What I like about their approach is the emphasis on shared intellectual values across disciplines, the importance of developing the lifelong habit of thinking critically, the attention to motivation, both in presenting your own views and in analyzing critically the perspectives of others, and the caution about attending to, and suspending, personal biases so that you can read and critique with an open mind.

Here are some suggestions for optimizing your contributions to your own scholarly and critical thinking community.

- Explore the world around you. Each of you is surrounded by a wealth of information about human nature, health challenges, social interactions, and change processes. Take a look around. Pay attention to diversity of experience and perspectives. Talk to friends and colleagues. Listen to what your clients/patients have to tell you.

- Research and investigate. Examine the professional literature to find out how others have conceptualized particular issues or concepts. Seek current research as well as seminal (i.e., earlier significant writings), nonmainstream, and interdisciplinary resources to help you address your topic both comprehensively and critically. Be sure to pay attention to diversity in research paradigms and procedures.

- Reflect on your own values and beliefs. How do your values, assumptions, beliefs, and attitudes fit with what you are reading and observing? Pay attention to those things that ring true to you. Pay attention also to the areas or issues to which you react or from which you disengage.

- Synthesize the material you have gathered. Identify key themes and critical points from your exploration and research. What main issues arise for you? Draw together these diverse points in an organized conceptual framework by identifying themes, patterns, relationships, or models that address your subject. Make sure to note those elements that do not fit or which continue to baffle you.

- Analyze the material. Identify and question the assumptions of any knowledge claim(s), acquaint yourself with the critiques made about that claim, and question the evidence or means by which it was established, as well as the assertions made from various types of evidence (i.e., avoid unwarranted leaps of logic). Demonstrate your analyses of other research or knowledge claims in the contributions you make.

- Adopt a point of view. Establish personal positions on the issues you are exploring. This does not need to be a permanent self-statement; in fact, as a critical thinker, you will likely continue to evolve your views over a lifetime. Nonetheless, you are expected to articulate your position clearly in the here-and-now. Illustrate how your exploration of various forms of evidence and thinking supports your point of view in defensible ways. Not taking a critical position on your subject is a position that you will be expected to support.

- Express your perspective with clarity. Be clear and concise. Take the time to translate jargon and to simplify difficult material. If you are unable to express meaning in your own words, you may not have fully understood the concepts. Above all, thoughtfully edit all contributions before you submit them.

A fundamental objective of critical thinking is to consider how, or whether, you might make personal and professional use of particular information. (Recall the focus on discerning appropriate information sources in Section 3.1.) Information must hold up under critical scrutiny and offer useful understandings of some aspect of professional theory or practice. Probing beyond the surface of any assertion requires discipline, and answering some of the questions in Exercise 4.5.2 as you read can be particularly helpful.

Choose a journal article on a topic in which you are interested or one about which you are currently writing. Apply the following questions to enhance your critical reading, thinking, and writing as you work through that article.

- What are the primary assertions being made by the author(s)?

- How clear, concise, consistent, comprehensive, and coherent are these assertions? Could you make these assertions understandable to someone unfamiliar with your discipline?

- How are these assertions supported? Do you agree with the evidence offered, and the way it was obtained (i.e., the appropriateness, and proper use, of the research methods used)? Are the author(s)’ claims fully supported by the evidence?

- What do other authors or researchers in the field think of these assertions and the evidence used to support them?

- What assumptions are implicit in these assertions? Do these have any cultural (e.g., ethnocentric, sexist, classist) or other blind spots? Do you agree with the relevance of the assumptions to the subject?

- How well do these assertions fit with your own values, beliefs, and worldview? Do they push you to consider personal cognitive, attitudinal, or behavioural change?

- What are the relative strengths and weaknesses of the assertions being made?

- What alternative metaphors, conclusions, or analogies for these assertions can you suggest? How can you develop these into other, more plausible, lines of thinking?

- Where, when, and with whom would the author(s)’ assertions not hold up? Why? Who might take exception with these assertions? Why?

- Do these assertions make a genuine contribution to better understanding the subject, even if they are different from understandings that are a better fit for you?

- How do these assertions look in practice? Would they be recognizable, generalizable, and usable?

In class discussions, group work, and written work, you are expected to go beyond what you have read to show others how you have made, or not made, information from various sources your own (i.e., how you have integrated it into your own thinking) and why you consider that information useful, or not useful, to you or others. This requires you to engage in the higher levels of learning (i.e., analysis, synthesis, evaluation) addressed in Section 4.1. Fowler (2005) articulated the relationship between these levels of learning, and I have adapted their material below.

- To synthesize material, you must first analyze it by breaking it down into its parts to understand its possible meanings.

- To evaluate material, you must first synthesize it by making connections among the parts, identifying relationships, and drawing out its implications.

- Evaluation takes critical thinking a step further by making supported judgments about the quality of the arguments, the validity of the conclusions and implications, and their significance to the body of knowledge in the health disciplines.

Fostering Cognitive Complexity

Engaging in critical reading, thinking, and writing requires you to be able to step back, to think about your thinking, and to identify barriers to critical thinking. One of those barriers is cognitive rigidity. Consider the following FHD Program Outcome, and then complete Exercise 4.5.3, drawn from Collins (2018a), to explore the skill of cognitive complexity further.

Cognitive complexity. Be tolerant of ambiguity, and foster cognitive complexity to enable you to see beyond your own values, worldview, and sociocultural contexts.

Think about your thinking by comparing and contrasting the characteristics of cognitive complexity versus cognitive rigidity below. Honestly appraise your own cognitive tendencies, and consider how these might be assets or barriers to engaging in critical reading, thinking, and writing. It is very important not to fall into either/or thinking; this applies to your thinking about thinking as well, because you will likely recognize both thinking patterns in yourself. Identify the contexts, relationships, issues, or other variables that might incline you towards one or the other. What meaning do you make of these observations? What are some implications of the cognitive style toward which you incline for your professional writing practices?

|

Cognitive Complexity |

Cognitive Rigidity |

|

|

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide (2nd ed.), by S. Collins (Ed.), 2022. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#feelsafe. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Applying a Critical Lens to Attitudes and Beliefs

In keeping with Bloom’s (1956) emphasis on affective learning, and as a member of an applied health discipline, you will also be challenged throughout your graduate program to reflect on the various lenses through which you view the world. You will be expected to reflect actively on cultural and social biases and to explore how those might affect the quality of your writing. The goal of self-reflection is not to move to a value-neutral position, but rather to move to a point of awareness where your own personal values can be consciously suspended temporarily, so that you can most accurately hear what is being said by others. You will also be expected to reflect on, and to evaluate critically, your own beliefs and values in light of professional literature, ethics, and values. For example, you might currently believe that people are poor, because they are too unhealthy to work. However, once you spend time exploring the professional literature, that belief will probably be turned on its head, and you will instead embrace the opposite assumption: Poverty is most often a precursor to ill health (Allan & Smylie, 2015; Collins et al., 2014; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2012). The expectation to reflect critically on your own attitudes and beliefs is reflected in the following FHD Program Outcomes.

Cultural diversity. Value, respect, and be responsive to cultural diversity.

Social justice. Take action to safeguard the welfare of others and to promote social justice.

Self-awareness. Value self-awareness, and engage actively in continued exploration of values, beliefs, and assumptions.

Critical thinking is the foundation and benchmark of graduate education! Your ability to read critically, think critically, and then translate your ideas into writing critically is what will make you a successful writer.

If you want to learn more about critical thinking, check out the work of Kevin deLaplante of the Critical Thinker Academy. He has created a playlist in YouTube of videos on critical thinking that offer a great alternative for those of you who are more visual or auditory learners.

You may also find the following resources helpful.

-

Massey University. (2018). Critical reading. http://owll.massey.ac.nz/study-skills/critical-reading.php

-

University of Toronto. (n.d.). Critical reading towards critical writing. http://advice.writing.utoronto.ca/researching/critical-reading/

-

Centre for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). Critical thinking – Description, analysis, and evaluation. https://rise.articulate.com/share/a8gHLBu3S8f4JqWw92kPR51CaPyBzmEA#/