Main Body

4

As you might already know, a large part of being an athlete is identifying as one. Elite athletes, and individuals striving to be, often take their identity very seriously on and off the court as they often represent more than just themselves. This can include their team, club, school name, coaches, teammates, and even to the extent of their fans, family, and friends. To ensure they can do and be their best during performance, they devote a lot of time and effort outside their sport to activities such as eating healthy, exercising regularly, and getting good sleep, among many others. When an athlete becomes injured, this can disrupt their life, and potentially their identity, which can be very difficult to work through and can even cause decreases in mental health (Putukian, n.d.). This is where executive functions and the use of them in specific activities can help rebuild the athlete’s identity and get their confidence in performance back.

There are many factors that help develop one’s identity. Some of the more commonly known ones include personal beliefs, self-awareness, and family roles. One factor that may not be as well known but is just as important to identity development is motor competence. Motor competence is defined as “an individual’s ability to move proficiently in a range of locomotor, stability, and manipulative skills” (Timler et al., 2019). People with high motor competence are often more motivated and confident in sport participation (Timler et al., 2019). This leads us back to athletes. When athletes become injured, it is possible for them to lose some of their physical fitness or athletic skills during recovery which can result in a variety of decreases in mental health such as general and performance anxiety, depression, and eating disorders. In a study about health-related quality of life, researchers determined that severe ankle injuries impact health-related quality of life, even after return to athletics (Marshall et al., 2020). As discussed in the summary of a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine, researchers have found that it is common for career-ending injuries to cause long-term psychological effects (Chang et al., 2019). So let’s dive deeper into how and why this happens to injured athletes.

Injuries are unintentional and generally unavoidable in athletics. Due to their often sudden nature, injury can expose or provoke various mental health issues (Putukian, n.d.). “When a student-athlete is injured, there is a normal emotional reaction that includes processing the medical information about the injury provided by the medical team, as well as coping emotionally with the injury” (Putukian, n.d.). Emotional responses to an injury can include but are not limited to, sadness, isolation, lack of motivation, frustration, sleep disturbance, and disengagement (Putukian, n.d.). However, every person is different in their response to an injury. It is important to understand that the time of response can vary as well, extending “from the time immediately after injury through to the post-injury phase and then rehabilitation and ultimately with return to activity” (Putukian, n.d.). The extension of emotional response through return to activity is problematic and is what needs to be focused on here. While it might seem obvious that anyone might be less confident when returning to an activity they have not done in a while, it can be extremely unsettling and stressful for athletes specifically because they hold such a strong connection to their athletic identity. It can initiate a vicious, self-defeating cycle where the athlete’s ability to engage in their sport negatively changes and this causes the athlete to lose confidence, motivation, consistency, and sense of self on and off the court just like our struggling athlete we are trying to help.

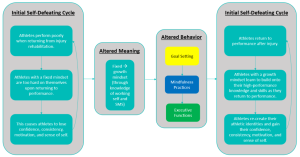

This is where the wise intervention framework comes back in. Through the wise intervention model, we can alter meaning and behaviors to turn the initial self-defeating cycle into a self-enhancing cycle for the athlete. In the logic model seen below in Figure 1, the initial self-defeating cycle can be altered through meaning-making. This is where the athlete’s fixed, amotivational mindset of failure, bad performance, and lost sense of self can be changed into a growth mindset through the knowledge of the Self Memory System and the working self. Once we have taught the athlete altered meaning, we need to teach the altered behaviors to go along with that. The altered behaviors in this model are goal setting, mindfulness practices, and executive functioning activities. Once meaning and behaviors have been changed, the athlete can move to a self-enhancing cycle where the athlete recreates her athletic identity and learns to build onto the high-performance knowledge and skills. Through this growth mindset, added knowledge, and new and improved self, the athlete gains her confidence, motivation, and sense of self back and returns to high-performance sport once again.

Figure 1. Wise intervention logic model for athletes.

We have already discussed mindfulness practices and goal setting in previous chapters, the last behavior that needs to be explained is executive functioning. Executive functions are mental functions that enable us to be reasonable and problem solve, exercise discipline and decision making, be adaptable and creative, among many other things (Diamond, 2014). There are three core executive functions which are working memory, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility. Working memory helps us make sense of things over time, allowing us to relate previous experiences to current ones. Inhibitory control allows us the ability to control our own attention, behaviors, thoughts, and emotions despite external stimuli or internal predispositions. Cognitive flexibility, or mental set-shifting, is the ability to sustain or shift attention based on demands. These are necessary for concentration, cognition, and control, and therefore are essential for school, work, and life success (Diamond, 2014). Executive functions are also critical for crime reduction, better mood, social support, and physical fitness (Diamond, 2014). As well as they are predictive of “achievement, health, wealth, and quality of life throughout life, often more so than IQ or socioeconomic status” (Diamond & Ling, 2016). There is also evidence that adults with better executive functions also have a better quality of life and happiness report (Diamond & Ling, 2016). Essentially, executive functions are at the core of life success which makes them important to understand.

Knowing how essential these are, the next logical question is can executive functions be improved? The short answer is yes. There is empirical evidence that various activities can improve executive functioning. For example, activities such as interactive computer games are a way to train task-switching (Diamond, 2014). Among the five principles for executive function programs, the most important is that “repeated practice is key” (Diamond, 2014). It is also important to note that when we are stressed, dopamine floods the prefrontal cortex, and “the activity of the neural circuit that includes prefrontal cortex becomes less synchronized” and therefore less effective (Diamond, 2014). Another example is “when we are sad or depressed, we have worse selective attention” which can be equally as detrimental to an athlete’s performance, then creating that self-defeating cycle (Diamond, 2014). Even though athletes can be injured enough to where they cannot play, they can still exercise their executive functions to feel a sense of comfort and accomplishment during recovery and allow them to recognize that not all skills and abilities have been lost during injury and time out of athletic performance. This is important to keep in mind as we continue to help the struggling athlete we have been discussing.

As athletes work through this workbook, it is beneficial for them to recognize the connections between the activities they are practicing and their sport or recovery process. Each set of smaller activities discussed so far, including mindfulness practices, goal-setting exercises, and executive functioning tasks, generalize and can be applied to each athlete’s sport. To be an athlete, you need to have control, attentional focus and flexibility, and working memory. This is exactly why it is important to continue to exercise your executive functions, even if it cannot be done in the way you normally do through your sport. Exercising your executive functions during recovery allows for a sense of accomplishment and comfort, which would be extremely valuable for the athlete we have been trying to help throughout this book.

With this evidence, what should be the next step in helping athletes mentally recover from injury? We have taught athletes about meaning-making and how to change meaning through a growth mindset, now let’s look at how we can help them alter behaviors through a workbook they can do on their own. The companion workbook contains a section for goal setting where the athlete can apply what they have learned to create their own effective goals and recognize their progress through reflection. The second section will include a mini quiz that asks the athlete to “Choose Your Own Adventure” based on their current physical activity level, due to injury, recovery stage, or doctor’s orders. Based on the athlete’s answers, this will lead them to different activities within mindfulness practices or executive functioning. The mindfulness section is where they can take some time to practice breathing, body scan, or self-compassion exercises, mindfully color, or take a mindful walk with space for reflection after each activity. The executive function section will instruct them to do some light-hearted activities that allow them to exercise their executive functions such as task-switching and be in a fun, positive environment. These include playing board or card games, actively playing the Simon Says game, or dancing around. The goal of this workbook is to encourage and support a positive environment as the athlete works on rebuilding their athletic identity. And while the companion workbook is a good place to start, all these activities can be done far past the use of this workbook. The hope is that athletes will recognize this as a starting point and continue to work some of these activities into their daily routines.