10

Brianna Buljung

This chapter will help you:

- Understand the methods academics use to convey their research to the public

- Reframe your research in terms of its impact on a public audience

- Prepare an elevator speech describing your work or professional interests

Introduction

We live in an era in which academic research, science in particular, has become a matter of belief rather than fact. Hypotheses, studies and findings are evaluated against the audience’s belief and personal values. Academic research is also often conveyed to the public by non-academics and non-experts. It is important for scholars to become comfortable communicating their research to the public to maximize the impact of their work.

There are a variety of different ways to communicate your research publicly. Digital formats can include blogs, websites, vlogs, news articles, webinars and social media. You may also find yourself communicating in person through interviews, one-on-one conversations and presentations to non-professionals. The value of each communication modality will depend on your discipline, research topic and communication styles of your intended audience(s). As you explore the different methods in this chapter, consider how you might use each one to share the impact of your research. Also, consider your level of comfort with using that platform to discuss your research. One form of communication, the concise statement or elevator pitch, can form the basis for all other public communication efforts. When crafting your elevator pitch, you will reflect on your research, specifically what aspects of it interest you. You will also reflect on its impact to different audiences. These considerations will help when conveying information about your research through other modalities.

This chapter will describe the importance of communicating academic research to audiences beyond your discipline. It will also discuss different modalities for communication and the strengths of each one. Finally, you will have the opportunity to reflect on your research and craft an elevator pitch that can be used to discuss your current research project or interests.

Why You Should Learn to Communicate Beyond Your Discipline

Effective research communication relies on describing your work in terms that an educated public can understand and relate to. You have to connect your work to people’s lives in meaningful ways by discussing the broader impact of the project. For many topics, academic research has become a matter of belief and has been undermined by politics. This is especially true for some types of scientific and medical research. COVID-19, climate change, vaccines, and even evolution are politically charged topics in many places. Social Science and Humanities research also face scrutiny as they address divisive topics such as critical race theory, free market economics, immigration and healthcare policy. Accessing misinformation and inaccurately reported research on these and many other topics can be detrimental to the public and potentially dangerous. Effective communication of credible, accurate research is important for and mutually beneficial to both the public and the researcher.

The benefits of research communication for the public can range from promoting understanding to demonstrating the impact of publicly funded work. Effective communication can promote understanding of different topics and inspire critical thinking about complex and timely topics. Widely sharing accurate academic research with the public will also impact the amount of inaccurate research being shared, especially in relation to science. Effective research communication can have long term effects, especially in inspiring young people to pursue careers in research. It can also demonstrate the value of funding research, which in many countries is subsidized by taxpayers.

Academic researchers also benefit from sharing their research with the public. Most significantly, it encourages academics to consider the larger implications of their work and its impact beyond that specific study or experiment. It also provides a venue for researchers to engage with the public on crucial issues. Over the long term, effective communication of accurate academic work can lead to increased funding for research and increase the public’s trust and respect for the field. Personally, researchers can benefit by practicing communication skills, reflecting on their work and ultimately renewing their excitement for their research.

Despite the need for and benefits of research communication, there are several barriers that can make the process difficult for academics. Within academia, there is very little credit awarded for researchers who devote the time to communicating with the public. At most institutions, it does not carry much weight in promotion and tenure considerations and often falls into the service category. Because it is not as highly valued as other forms of communication, such as peer reviewed journal articles, many researchers struggle to devote the time necessary to establish their reputation with the public and to communicate successfully. The skill of effective research communication is also not often taught in higher education. Translating lab work or research results into terms understood by an educated public may be difficult or unnatural for many academics. It can also be difficult to learn the balance between adequately describing the research and making it interesting for the public. Many academics also fear some of the potential consequences of sharing their research publicly. There is a chance the study could be misrepresented by the media or attacked by skeptics. In some countries, academics may fear reprisal from the government for controversial research. The barriers to successful research communication need to be carefully navigated to convey the impact of your research to those beyond your discipline.

While it is important to be able to communicate your research to the public, these skills are also useful when discussing your research with professionals beyond your discipline. At different times in your career, you may need to present your work to institutional administration, grant funders or potential industry partners. You might also need to communicate in commonly held terms to engage with potential collaborators from other disciplines. Impact is the central focus of this type of engagement. You must effectively sell the impact of your work to institutions, companies, funders or collaborators.

Different Ways to Communicate Research Publicly

There are many different ways that academics can communicate their research to a broader audience beyond their specific discipline. Communication modalities are tools for finding and reaching your target audience in a format that suits their needs. It would be very difficult for the average researcher to effectively communicate in all modalities, so choose platforms carefully.

There are three primary aspects to consider when choosing a communication modality. First, determine where your target audience would look for information on your topic. For example, you might choose Twitter to communicate with Americans but would want to use Weibo to share your work in China. Second, consider how much interaction you want to have with your audience. For example, are you interested in allowing comments from readers? If you would like to allow comments, select a platform that will facilitate that, such as a blog or social media. Utilize more static modalities such as a website or news site if you want the communication to only flow towards the public. Finally, consider and choose platforms that you are comfortable using. You may only be comfortable contributing to the blog for your professional association. Alternatively, you might be interested in communicating across several platforms to maximize your reach. The following list contains examples of several communication modalities and the strengths and weaknesses of each as a means of communicating academic research.

Academic Blogs

- Example: PLOS Blogs

- Strengths: posting on an established blog, such as one hosted by a professional society or publisher, is a relatively easy way to communicate with the public; sought out by an audience with a specific interest in the topic; can invite comments and engage with readers

- Weaknesses: if you do not post on an established blog you will need to build up your following; unless used in conjunction with social media audiences may struggle to find your content; unless carefully moderated you may experience trolling in comments

Vlogs and Video content

- Example: Minute Physics

- Strengths: can describe your research in easily viewed segments; you might be able reuse your content in your teaching; easily embedded in websites and social media platforms like YouTube allow for commenting

- Weaknesses: can take considerable time to create and edit; may require specialized software for visualizations and video editing

Website

- Example: MIT Materials Research Laboratory

- Strengths: static, one way communication with your audience; you can link to full studies; your CV, videos and other relevant content can be located in a single place

- Weaknesses: requires maintenance to ensure content is up to date; may require hosting fees and compliance with institutional web branding standards

Social Media

- Example: Academics Say

- Strengths: brief posts allow you to easily and quickly share your research; ability to embed video or link to additional content; engaging and allows for two way communication with the audience; you can create your own channels and accounts or contribute to established accounts

- Weaknesses: establishing and maintaining a following can be time intensive; content constantly has to be updated; can invite trolling and negative feedback; can be difficult to separate from private, personal accounts

News Media

- Example: Carbon capture story in the Guardian

- Strengths: mainstream news has a broad reach enabling the audience to find and learn more about your work; succinctly captures research findings and their impact on the audience

- Weaknesses: can be oversimplified or mischaracterized; rarely is the researcher communicating directly with the audience, instead a journalist is serving as intermediary; you may not have control over the content of the published story

In Person Public Event

- Example: Denver Museum of Nature and Science events

- Strengths: interested audiences seek out this type of event; often advertisement is done by the hosting organization; opportunities for engagement via questions during the event; can foster an interest in the topic by younger audience members

- Weaknesses: may be difficult to find a local organizational partner that aligns with your research areas, can be time consuming to prepare and present

All types of research communication require the time and effort to ensure you are maximizing your research impact. Explore platforms and modalities to find the best avenue to connect with your intended audience. Also, consider how much effort you want to invest in your professional brand. Do you want to gain a large public following or be recognizable by the public as an authority on the topic? If so, you will need to carefully cultivate a brand across platforms. This often requires regular, engaging posting on various social media platforms and linking back to your work on more static platforms. Some researchers thrive in this setting, but others may not have the time to devote to this work. If you fall into the latter group, find established blogs, social media channels and websites that you can contribute to.This approach lessens the amount of work needed to establish a brand, and actively manage web content.

Academic research in the news can often be oversimplified or mischaracterized, contributing to public trust issues. Research presented in the news is typically not written by the researcher who conducted the study or by someone with an academic background in that discipline. Scientific research in the news tends to focus just on novel or exciting findings, selecting elements of larger studies that contextualize those findings. Social science and humanities research stories in the news tend to focus on controversial topics and findings; often sensationalizing study findings. As an academic researcher, you will find yourself communicating with the journalists who then communicate with the public. Whenever possible, ask to review draft stories and provide feedback to ensure the story contextualizes your findings and accurately describes the research. Ask journalists to link to your website or the full research study so that interested readers can learn more about the project. You can also use the various communication methods above to call attention to news stories that misrepresent the research in your field. For example, the Twitter account @justsayinmice brings attention to news stories that make bold claims about scientific findings without explaining that the study was conducted on mice.

How to Craft Concise Statements about your Research

At times, you may want to discuss your research and/or career interests with individuals. It can be helpful to prepare a concise statement, colloquially known as an elevator pitch, that you can use at conferences, in your biography or when meeting potential collaborators. This statement needs to quickly and effectively introduce your research, its impact and the potential value to the listener or reader. Being able to discuss your research concisely will help you to connect with listeners who are interested but may not necessarily have the same level of subject matter expertise as you do. It can also help you to connect to potential collaborators in adjacent or related fields who might be approaching the topic from their disciplinary perspective.

Regardless of the discipline, most elevator pitches contain some of the same attributes. They are inherently concise. You are not describing your entire study or specific results; you should aim to limit the entire statement to 3-5 sentences. They also are confident and leave a memorable impression with the listener or reader. You have to confidently convey your research interests and expertise. Finally, they invite further discussion about your work. Your concise statement, or pitch, opens the conversation about your work and its potential impact on the reader.

You may have used some form of the elevator pitch in the past, either in casual conversation or in a more formal setting. The pitch can be used in job interviews to respond to questions such as, “tell me about yourself”. You may also briefly describe your work to your advisor, classmates or colleagues at your institution. These experiences can be a good place to start from when crafting your pitch. As with many other aspects of the research lifecycle discussed in this book, begin with reflection. Ask yourself two questions about your research: 1) What interests me about this topic, and 2) What impact does this project have beyond this paper or my research group? The answers to these questions will form the basis of your pitch. By understanding your interest, you will be more confident and engaging in your delivery. Understanding your impact will make the pitch more engaging for the audience.

You also have to know some basic characteristics of the audience(s) you will be using the pitch with. Depending on the stage in your career, your professional goals and the topic of your research, you may need to develop multiple pitches to suit the needs of different audiences. For example, you may need a statement that can be used with the general public or students and another that is for academics in an adjacent field. In the first you will avoid as much disciplinary jargon as possible to ensure your work is understood, while with the second group you may use some jargon that is commonly understood. As a rule, avoid jargon, formulas and overly specific terminology whenever possible in your pitch. This will maximize the audience and ensure that your message is clearly conveyed.

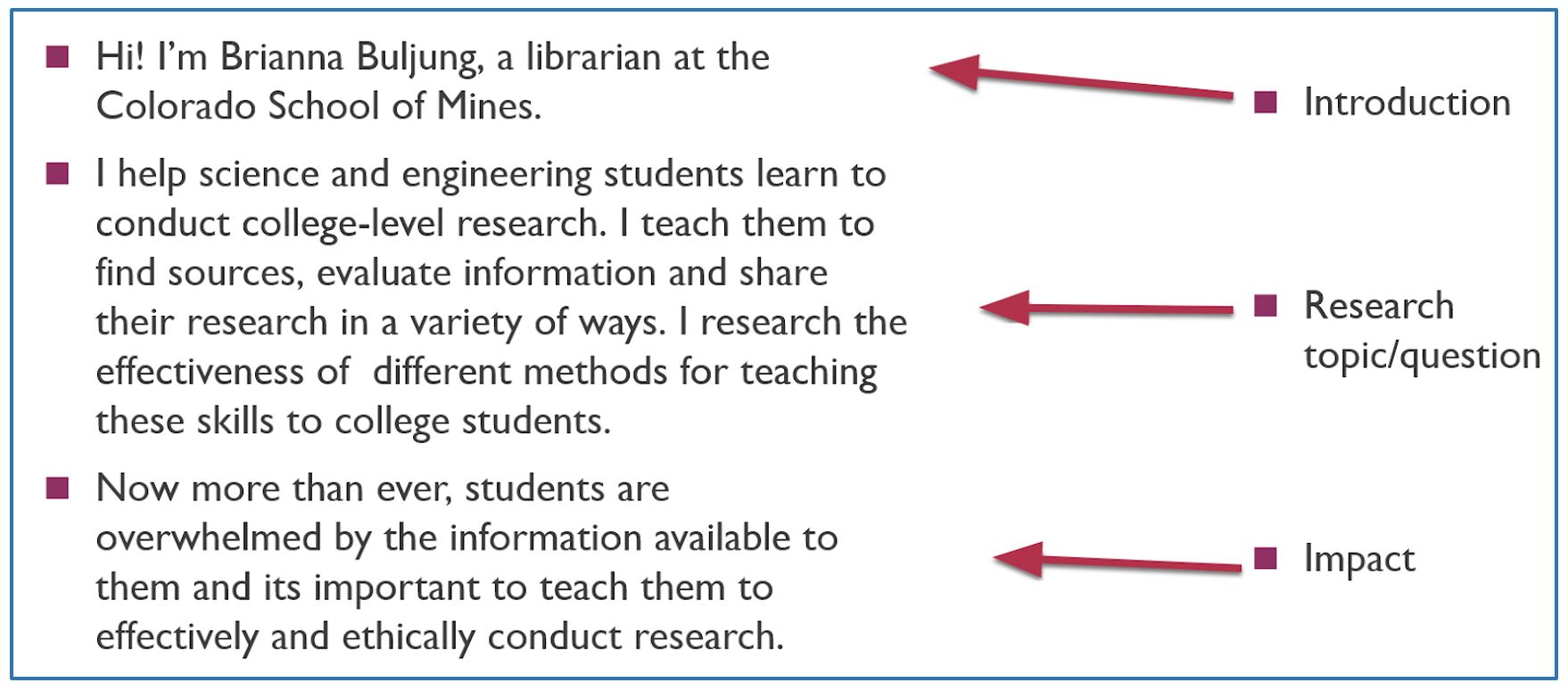

The typical elevator pitch has 3-5 sentences that can be broken into three distinct parts, the introduction, research topic description and impact statement. The graphic below breaks the pitch into these parts. Your statement may look more like a paragraph.

The first part of the statement is the introduction. In approximately one sentence, you introduce yourself, position and affiliation to the audience. These details will depend on the specific audience. For example, will they be familiar with your specific title? When I use the pitch for other librarians, I tend to use my formal title, as they are more likely to have someone in that role at their institution. For other audiences, I simplify it to librarian or engineering librarian. Also, your affiliation might change slightly. For audiences internal to your department or institution, you may use your research group or department as your affiliation. For broader audiences, you probably want to use your institution. Basically, use the title and affiliation most likely to resonate with your audience.

The second part of the statement is a very brief introduction to your research topics or professional interests. Remember – this is a very concise statement and the presentation of your topic will be approximately 1-3 sentences. In this portion of your elevator pitch you can discuss your research question or hypothesis, interesting questions raised by your research, potential solutions you’ve found or how your work fits into the broader understanding of the topic. The terms you use will be dictated by the audience. You will need to use different terminology than you might normally when talking to professionals in a different discipline or to the general public.

The final sentence of your statement is focused on the impact of your work. In this sentence you are indicating why the audience should care about your topic enough to engage in further discussion with you. When crafting this portion of the statement, ask yourself the following:

- Why does my research matter?

- Why should my audience care?

- What do I want the audience to remember about me?

Answering these questions in relation to your specific audience will help you to leave a lasting impression and invite further discussion of your work.

Your finalized elevator pitch should be unbiased, engaging and brief. Carefully craft it to ensure that it is relatable to your audience. Many early career researchers may find it necessary to have a couple different versions of their statement ready for use at conferences, when talking to the general public and for conversations around campus. Practice your statement until you are comfortable with delivering it without sounding rehearsed. Although the elevator pitch is just one type of communication with those beyond your research group or discipline, it can form a foundation for communicating widely through other means as well.

Tips for Sharing Your Research with Non-Academics

To effectively share your research beyond your discipline, remember:

- Work carefully to communicate accurate, ethical research findings that demonstrate the impact of the work on the audience.

- Regardless of the format, you need to have a basic understanding of your audience in order to tailor the message about the impact of your research.

- Choose modalities that you are comfortable using while maximizing the impact of your effort. Consider whether you want to allow for public comment alongside your work through a modality that allows comments and/or reposting.

- Use the modalities that your audience is using, this may vary depending on generational, cultural and political norms. This makes it easier for the intended audience to find and use your work.

- Whenever possible, use engaging graphics that bring attention to the research data and its impact on the audience.

- Your elevator pitch(s) should concisely and confidently convey your interest in your research topic as well as potential impact on the audience. Avoid over-explanation and use of technical jargon.

Reflection

Now that you have a more in depth understanding of sharing your research beyond your discipline, consider the following in relation to your own career and professional goals:

- Reflect on your own research interests and consider what portions of it might interest the a wider audience and/or how it might impact the public in some way

- Practice translating your own research for a public audience using an example of your work:

- Focus on your abstract, introduction and conclusions

- In a few sentences describe the research and its impact

- Remember to avoid jargon and make it interesting

- Craft a concise statement related to the work example you used in #2:

- Dissect it to ensure you have all the necessary components

- Practice it with someone who is not familiar with your research