The concept of cultural safety has been foregrounded most explicitly and consistently in dialogues about the relationship of Indigenous people and peoples to healthcare systems and practitioners (Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association [CCPA], 2016; Fellner et al., 2016; Reeves, 2018; Shah & Reeves, 2015). The First Nations Health Authority (n.d., Definitions, para. 1) assert that “cultural safety is an outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in the healthcare system. It results in an environment free of racism and discrimination, where people feel safe when receiving health care.” Cultural safety also involves a strengths-based approach in which counsellors actively invite attention to client cultural identities, worldviews, and values and create space for client healing traditions, practices, and community supports (Northern Health BC, 2021).

Chapter 3 Creating Safer Healing Spaces

by Gina Ko, Sandra Collins, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Lisa Gunderson, Amy Rubin, Lisa Thompson, and Leah Beech

In this chapter we begin to move from initial engagement with clients into relational practices that support the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences. We have devoted this entire resource to relationship building and generating a shared understanding of client challenges and visions for change. We encourage you to take the time to really listen to your clients so that you avoid falling short of a comprehensive and contextualized understanding of their needs. We do not move into describing change processes in this ebook. Rather we guide you systematically to the place where you understand clients’ current lived experiences and have a shared sense of direction for the change(s) they anticipate or desire.

In this chapter we combine the initial processes for understanding client presenting concerns with the need for creating cultural safety. We highlight cultural safety early in the process of centring relationships in counselling, because we recognize the current and historical embeddedness of healthcare professions and institutions, including counselling and psychology, in eurocentric and colonial worldviews. This positioning has brought with it barriers to equitable access to health services for many people and persons whose dignity and rights are not consistently acknowledged and respected (e.g., women, persons with physical disabilities, those with mental health and addictions challenges, members of the queer community, Indigenous people, people of colour, the working poor, the unhoused).

Establishing a sense of cultural safety with clients is an ongoing process, and therapists’ cultural self-awareness is essential for creating safer conversational spaces. We encourage you to consider how your own cultural and social positioning influences what you bring to the counselling process. The key concepts in our vision for this chapter are overviewed below.

Figure 1

Chapter 3 Overview

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

When clients come to counselling, they engage in a relationship with another person with whom they are expected to take risks by sharing parts of their stories, by allowing another human being into their thoughts and feelings, and by accepting change-focused queries into their lived experiences. It is import for counsellors to remember and to honour the vulnerability and risk-taking involved in entering into a therapeutic relationship. One of the important ways of doing this is through creating a climate of cultural safety in which all clients experience respect, are treated with dignity, and are invited to bring their cultural selves into the counselling process. In this chapter we examine how building cultural safety establishes a foundation for understanding client presenting concerns.

A. Creating Cultural Safety

We all deserve to feel safe

Consider the explanation of cultural safety so eloquently expressed in this video from Northern Health, BC.

© Northern Health BC (2017, February 14)

Reflect on aspects of your personal cultural identity that might leave you feeling unsafe in certain healthcare settings. Then review this news story and accompanying video: The discrimination suffered by an indigenous woman at a Joliette Hospital has sparked outrage across Quebec. Imagine what it would be like, in your most vulnerable moments, to experience marginalization and discrimination based your cultural identity. Identify two specific intentions for creating cultural safety in your relationships with your clients, being as specific as possible.

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2022. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#feelsafe. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Collins (2018d) argued that all counselling is multicultural because there are always visible or invisible differences between clients and counsellors in terms of the intersectionalities of gender identity and sexuality, age, ability, social class, religion and spirituality, as well as ethnicity or Indigeneity. In this sense cultural safety is a concept that applies to all client–counsellor relationships. Cultural safety is both an ongoing relational process and an outcome of the counselling process. Similar to the development of trust, it is the client who decides if the relationship, or a particular counselling process, is culturally respectful and safe. In practice this means that counsellors can build a broad foundation for cultural safety in their practices; however, providing an environment that supports cultural safety requires ongoing responsiveness to each unique client they encounter.

1. Cultural Self-Reflection

As noted in Chapter 1, we assume that learners accessing this ebook have a basic foundation in multicultural counselling theory and practice. Sensitivity towards clients’ cultural identities and social locations is not possible without counsellor awareness of themselves as cultural beings and acknowledgement of their potential for cultural biases. We are writing this ebook in the midst of a global pandemic, which has cast a brighter light on long-standing issues of systemic racism in Canadian and around the world. As we consider the importance of cultural safety in counselling, each of us must position ourselves in relation to existing cultural and systemic racism. We are deliberate in making our personal/professional values transparent as the authors of this ebook. We invite you to engage in cultural self-reflection as Dr. Lisa Gunderson speaks from her position of expertise on anti-racism in the video below. You will encounter two other videos, which build on this one, in later chapters.

Contributed by Dr. Lisa Gunderson

Dr. Gunderson models the process of cultural safety beginning with her territorial acknowledgement, through which she invites you to reflect on your role in disrupting the processes of colonization, one of many forms of systemic racism in our society. She then invites you to consider whether or not you will actively choose to be an anti-racist counsellor. As you watch the video, observe and record your cognitive and emotion responses.

© Lisa Gunderson (2021, February 9)

Take a few moments to reflect on the following prompts, taking into consideration both your thoughts and feelings.

- Dr. Gunderson argues that there is no neutral stand on racism. Consider carefully the implications of this assertion for how you see yourself as a person and as a practitioner.

- How comfortable are you with becoming uncomfortable? What does your gut response to the messages in this video tell you about what it might be like to unpack further your unconscious biases, including racism?

- From your current place of personal and professional self-awareness, how do you understand the difference between not having negative intent and adopting an active anti-racist positioning?

- We will revisit the issue of power and privilege in Chapter 4. For now consider your positioning of privilege in relation to what it might mean for you to embrace more fully an anti-sexist, anti-racist, anti-ageist, and so on perspective as a foundation for creating a more culturally safe space for your clients.

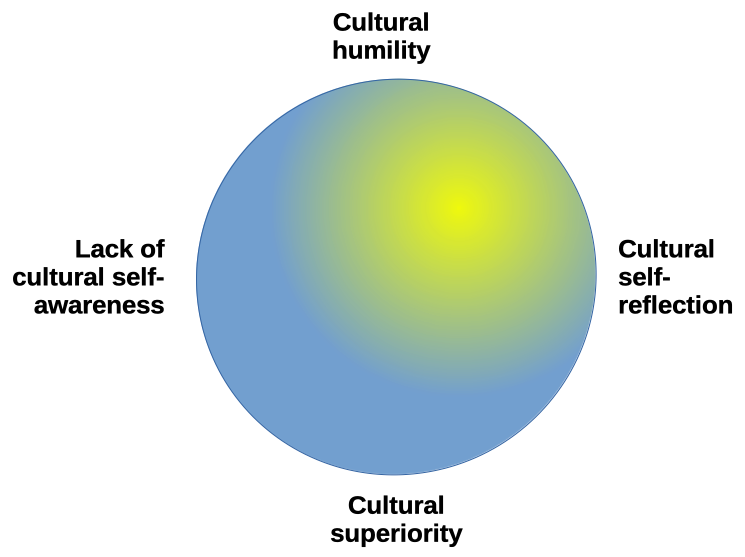

2. Cultural Humility

Parrow and colleagues (2019) identified cultural humility as one of eight evidence-based relationship factors of importance to both the counselling relationship and to counselling outcomes. Reflect on the videos above (cultural safety and anti-racism) as you consider the definition of cultural humility as “a process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases and to develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust. Cultural humility involves humbly acknowledging oneself as a learner when it comes to understanding another’s experience” (First Nations Health Authority, n.d., “Definitions” section, para. 2). Central to this definition is moving from a position of self-orientation to other-orientation (Hook et al., 2016; Parrow et al., 2019), which is foundation to the client-centred, responsive relational practices we introduce throughout this ebook. Collins (2018b, 2018c) positioned cultural humility as foundational to cultural competency, reminding counsellors that competency is not just about doing, but also about being. Counsellors who embrace a position of cultural humility are more likely to employ other relational practices like cultural curiosity and a not-knowing stance, which together counteract ethnocentrism and make it less likely for them to engage in unintentional cultural oppression.

As you dig deep into your own attitudes and beliefs in this chapter, we invite you to consider situations in which you might be challenged in developing rapport and trust with clients or in creating a climate of safety in the client–counsellor relationship. Clients may come to counselling with preconceived ideas or expectations about how they will be treated, based on their previous experiences in healthcare settings or other systems. It is important to think ahead to how you will respond to clients who come to you from a position of learned or earned distrust. In some cases client distrust may have nothing to do with who you are as a counsellor; in other cases you may hold privileges and social locations that implicate you in client oppression.

In the video below Amy Rubin reflects on her work with clients who have been mandated to engage in counselling. Although the source of distrust may differ, attend to how you might apply the practices she introduces to other situations in which trust is more directly tied to a lack of cultural safety.

Contributed by Amy Rubin

Not everyone who comes to counselling wants to be there. In this video Amy talks about her experience building rapport and trust with clients who feel angry and hostile toward the counselling process, because they have been mandated to attend. Sometimes this hostility can be expressed toward the therapist.

© Amy Rubin (2021, April 6)

This is a situation in which you might lose sight of how to treat everyone you encounter with respect and dignity. It would also be very easy to let a spark of personal reactivity build that interferes with you staying present and offering a sense of safety to the client.

Take a moment to picture a situation in which another person’s anger or distrust, justifiable or unjustifiable, was directed at you. Imagine yourself back in that situation. What emotions were sparked in you? When you feel the emergence of uncomfortable emotion, are you inclined towards a fight, flight, or freeze reaction? What does this tell you about how you might react, internally or externally, to clients who spark similar emotional reactions.

Breathe again, and reflect on the calm presence that Amy modelled in this video. What lessons can you carry forward for meeting all client from a place of compassion and understanding to build rapport and trust. How might you practice these emotional and relational responses before you encounter a challenging situation with a client?

Reflecting on cultural humility and cultural safety

To reinforce the internalized, attitudinal, and being components of cultural humility, Parrow et al. (2019) contrasted cultural humility with cultural superiority. As noted above, cultural humility is also intimately associated with engagement in cultural self-reflection. We invite you into the necessary discomfort Dr. Gunderson talked about above as you reflect honestly on where you might fall on the visual representation of these concepts below. Attend to your various dimensions of cultural privilege, which may shift your positioning within the circle. Consider the implications for clients of positioning yourself at various points within the circle. Dig deep to consider the degree to which you believe your lived experiences, worldview, values, or cultural norms and practices are more valid than those of other persons or peoples. To reinforce further the connection between cultural humility and cultural safety, reflect on your experience in the client role in counselling. [If you have not been for therapy, replace the counsellor with a teacher, a healthcare practitioner, or another person in authority.]

To reinforce further the connection between cultural humility and cultural safety, reflect on your experience in the client role in counselling. [If you have not been for therapy, replace the counsellor with a teacher, a healthcare practitioner, or another person in authority.]

- Recall a time when the counsellor engaged with you from a place of cultural humility (attending retrospectively to what this might look like in practice). What was your response to this experience? To what degree did their positioning enhance your sense cultural safety.

- Then identify a time when you felt uncomfortable or unseen in that relationship. Consider how counsellor power or privilege may have played into your reactions. What did you experience, cognitively and emotionally, in those moments?

- How do these experiences resonate with, or reinforce, the interconnectedness of the concepts of cultural safety, cultural awareness and sensitivity, and cultural humility?

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

As we shift our attention now to the counselling process, we pull forward some of the themes related to cultural safety as we conceptualize client lived experiences and deepen understanding of client presenting concerns from a client-centred, responsive, and relational perspective.

A. Conceptualizing Client Lived Experience

As editors of this ebook, we had many conversations about the language we use to describe various aspects of the counselling process. We have made choices to employ, purposefully and critically, the terminology used in this ebook. We refer deliberately to languaging to reinforce the active process of choosing appropriate words and phrases to support our intentions and the outcomes we anticipate. For example, we introduce the word challenges instead of talking about client problems to foreground the strengths-based approach for which we advocate. We also use the phrase conceptualizing client lived experiences in place of the common terminology of case conceptualization to avoid the potentially depersonalizing or dehumanizing associations that may accompany referring to clients as a cases. As you move through this chapter, attend to the goodness of fit of the languaging we have chosen to explain elements of the counselling process with your worldview, your theoretical positioning, and your beliefs about counselling practice. What resonates for you? What different choices might you make? How might you justify those choices from a values-based perspective?

In this chapter through to Chapter 10, we anchor the early elements of the counselling process in the broad framework of conceptualizing client lived experiences. One of the emergent themes in the common factors literature, dating back to the work of Jerome Frank in the 1960s, is the need for therapists and clients to come to a shared understanding of a “plausible explanation” (Poster, 2019, “Common factors,” para. 3) for the challenges the client is facing and a way forward to address those challenges. From a common factors perspective, the ways in which client challenges are conceptualized and the rituals or processes envisioned to support change may vary; what is important is active engagement of counsellor and client in a process of conceptualization of client lived experiences that is transparent and that both the counsellor and client believe will support or restore health and well-being (Poster, 2019).

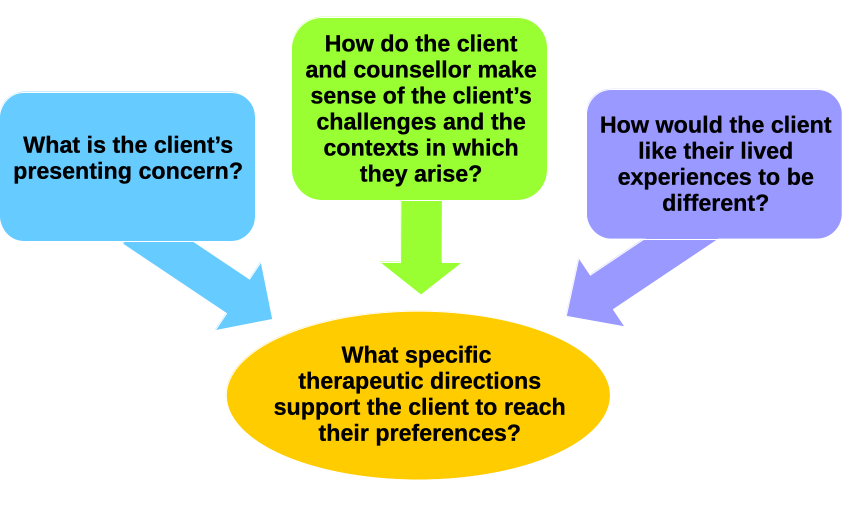

The atheoretical or transtheoretical position noted in the video above is grounded in the collaborative and culturally relevant process between client and counsellor of shared meaning-making about client lived experiences. We are not suggesting that counselling theory is unimportant; rather, we assert that if the therapist imposes a theoretical explanation that is not meaningful or culturally responsive to the client, it is unlikely to lead to client satisfaction with, or positive outcomes from, the counselling process (Poster, 2019; Nuttgens et al., 2021; Norcross & Wampold, 2018). The overview of the collaborative process of conceptualizing client lived experiences in Figure 2 below is adapted from Collins (2018a). We will revisit this process throughout the remaining chapters.

Figure 2

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

This image is described in the audio below.

The first step in conceptualizing client lived experiences is answering the question: What is the client’s presenting concern? (upper left). This will be our focus in this chapter. In Chapters 4 through 9 we focus of various domains of experience (e.g., emotion and embodiment, thoughts and beliefs) to support a multidimensional understanding of client lived experiences in response to the second question: How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise? (upper middle). In Chapters 8 and 9 we pay specific attention to the ways in which culture, social location, and other contextual or system factors further enhance this shared understanding. In Chapters 8 and 9 we also examine the third question: How would the client like their lived experiences to be different? (upper right). Then in Chapter 10 we draw on our evolving understanding of each element to begin to envision responses to the final question: What specific therapeutic directions support the client to reach their preferred futures? (lower middle). As Collins (2018a) noted, these are not fixed steps, even though we address them in an incremental fashion in this resource; they may be fluid and iterative throughout the counselling process.

Please note that we do not move into talking about change processes, in the sense of specific counselling interventions, in this ebook. Our focus remains centring relationships as a foundation for coming to a shared understanding of client lived experience, from which foundation counsellors and client can then collaborate on designing responsive change processes (Collins, 2018a). However we also believe that the counselling relationship, in and of itself, is a powerful tool for supporting client growth and healing (Feinstein et al., 2015; Norcross & Wampold, 2018). In this sense change is likely to begin for many clients from the moment they are welcomed into a culturally safe, client-centred, and responsive counselling relationship.

B. Understanding Presenting Concerns

We begin to engage in the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences in this chapter by introducing a number of counselling practices and microskills to support understanding of the first question in Figure 2: What is the client’s presenting concern? The process of information gathering is common to all approaches to counselling. Asking clients for information is premised on two other critical practices: (a) explaining carefully the limits of confidentiality in terms of the information clients provide and (b) ensuring that they have consented to both information gathering and engaging in other counselling processes in a fully informed way.

1. Information Gathering

There are many different approaches to gathering information related to client presenting concerns, ranging from formal, standardized intake interviews to much more casual conversational inquiry processes. The nature of the information gathering process may be influenced by broader contexts (e.g., agency policies, intake roles, funding requirements). In all cases, however, the process of gathering information from the client continues throughout the counselling process, with new information contributing to the evolution of shared understanding of client lived experiences. We argue that the process of information gathering is more likely to reflect the principles of cultural safety, introduced above, if it is approached from a relational perspective.

Information gathering from a relational perspective

Reflect on the following questions as you paint your own picture of information gathering within the context of care-filled, culturally safer, and responsive relationships.

- What rights to do you assume as a healthcare practitioner over information about your clients?

- Who should decide what information is relevant to a particular client’s presenting concerns? How might you broaden the frame of reference to consider other information while demonstrating deep respect for client rights to privacy?

- How might you approach information gathering in a way that signals to the client permission to not answer a particular question or to draw boundaries around what they choose to disclose or not disclose?

- How important is it to you that a client be able to tell a congruent story about their lived experiences? What might you learn about them by leaning into and welcoming incongruence or gaps in the story?

- How comfortable are you with accepting “no” from a client when you ask for particular information? How might your response in-the-moment build connection and a sense of safety? What types of counsellor responses might result in relational disconnection?

- How might your theoretical orientation, and in particular your view of health and healing, influence the information you believe is relevant or even critical to conceptualizing client lived experiences (see Figure 2)? What are the implications of a mismatch between your views of health and healing and those of the client?

- What specific attitudes, dispositions, or relational practices might support you to engage in care-filled, culturally responsive, and respectful conversations with clients to support them to share their lived experiences?

We remind you of the central question introduced in Chapter 1: How can I shift, adapt, or alter my ways of being, relational practices, and approach to counselling in response to the specific cultural identities, contexts, values, worldviews, and needs of the specific client with whom I am working?

We will return to the process of gathering information in the applied practice activities later in the chapter.

2. Limits of Confidentiality

Talking with clients about the limits of confidentiality within the counselling process is an important aspect of creating a sense of safety. It is also an essential prerequisite to asking clients to share information with you about themselves and their presenting concerns. As a practitioner, it is very important that you yourself are well-informed about your profession’s ethical guidelines related to the limits of confidentiality, the policies and practices in your place of employment, and the specific legal requirements in your region. Clients often come to counselling without a full appreciation of what is meant by the concept of confidentiality or what the limits are to the counsellor’s commitment to client confidentiality. It is important to take the time to consider both of these concepts with each client and to ensure that they have been understood fully.

Talking about the limits of confidentiality with clients

In this first video Gina provides her client with information about the limits of confidentiality in a way that is concise and accurate. Pay attention to what might be missing from a relational perspective.

© Gina Ko & Lisa Thompson (2021, March 29)

In this retake of the conversation, Gina focuses less on simply providing information and more on attending to Lisa’s reactions to the information and inviting dialogue about the meaning of the information. What do you notice about the change in Gina’s approach and in Lisa’s engagement and response?

© Gina Ko & Lisa Thompson (2021, March 29)

For Lisa the limits of confidentiality seem clear and reasonable. Take a moment now to picture yourself coming into counselling from one of the following social locations:

- a refugee fleeing political violence in a country where government and other authority figures are not to be trusted;

- an Indigenous person from a northern community in Canada, who has been forced to relocate to the south, because of ground water contamination from toxic waste from mining projects;

- a single mother who has had negative encounters with social services, because she is struggling to balance working three jobs to provide for her kids with ensuring appropriate after-school care; or

- a trans person who has had a series of negative encounters within the healthcare system and is coming to counselling as part of the requirement to qualify for gender-affirmative surgery.

What might you need from the counsellor to move forward within the boundaries of the limits of confidentiality? How might the therapist provide you with that sense of security and trust in the process, grounded in principles of cultural safety?

3. Informed Consent

Embedded within the process of detailing the limits of confidentiality is the necessity, from an ethical and legal perspective, of obtaining informed consent to proceed with the counselling process (Robinson et al., 2015). You’ll notice in the video on limits of confidentiality that Gina reinforced the ongoing process of informed consent (Chew, 2018; Nuttgens & Smith, 2016), making sure that Lisa understood that she could withdraw or renegotiate consent at any time and that Gina, as counsellor, would regularly revisit the issue of consent throughout the counselling process. The microskill of transparency, which was introduced in Chapter 2 is particularly useful when describing the limits of confidentiality and introducing other elements of the counselling process for which it is appropriate to solicit ongoing informed consent.

The concept of informed consent cannot be separated from other relational practices in counselling, particularly attention to the relative power and privilege of counsellor and client. This relative power extends beyond the positional power that is inherent in the role of healthcare provider to include the sociocultural construction of power reflected through client–counsellor social locations (Chew, 2018). Returning to the concept of cultural safety, it is important to for the counsellor to reflect critically on what each client might need in order to be able to provide truly informed consent. To support clients in the process of informed consent, counsellors might invite cultural healers into the therapeutic circle or seek out an elder to review cultural practices related to gaining consent and providing confidentiality. Similarly in school and community settings, where your client(s) may be a group of people rather than individuals, consultation is often critical to providing ethical practices in informed consent and confidentiality.

Reflections on informed consent and confidentiality:

- How might you ensure that your use of consent and confidentiality are culturally appropriate?

- What other services in the community might you draw on for insight into how they use, or engage in, the informed consent process?

- How might you support such services, if appropriate, to enhance the cultural responsivity of their practices?

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

The microskills introduced in this chapter are designed to enhance your ability to engage in collaborative conversations with clients for the purpose of understanding their presenting concerns. As we introduce new microskills, we copy rows from the Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary. You will want to look at this summary periodically to position these skills in context.

A. Responsive Microskills

1. Questioning

Most counsellors-in-training are curious about client lived experiences and easily move into asking questions. Well-positioned and intentional questions can create space for clients to tell their stories, and they can help tease out details or invite consideration of different perspectives . However the goal of questioning is not to conduct research by simply gathering as much information as possible. Skillful counsellors use a variety of questions, strategically positioned within the client–counsellor dialogue, to support specific client-centred outcomes. Care-filled questioning can support clients to examine more fully their lived experiences, offering them an opportunity to discover, revisit, connect, or critique thoughts, feelings, values, behaviours, interpersonal interactions, and so on.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Question |

|

|

|

Questioning: A foundation for information gathering

Animated video

In the video below you will meet George. George’s counsellor uses primarily the microskill of questioning. The questions used in this video reflect the process of gathering information about family history and context that is often an important aspect of understanding client presenting concerns.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 12)

Notice in the first interaction, how the counsellor drew on transparency (from Chapter 2) to suggest a direction for the counselling conversation and then used the microskill of clarifying (introduced below) to ensure George’s consent to head down that conversational path.

Questioning: An open invitation for dialogue

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this next video Sandra invites Gina to begin expanding on her presenting concerns by using only the microskill of questioning. Notice that Sandra uses a variety of questions starting with who, what, where, when, or why. These questions provide direction for the dialogue and encourage Gina to expand on her lived experience. These questions are considered more open and invite forward client-directed information.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, May 15)

It is possible to carry on a conversation by using only the microskill of questioning. However there is a fine line between questioning and interrogating. The best guide in this regard is responsivity to the particular client you are engaged with in-the-moment. This requires you to attend carefully to both nonverbal and verbal communications from the client, to consider cultural contexts (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, social class), and to attend to the quality of the relationship moment-by-moment, rather than simply attending to the exchange of information. Another risk with over-use of questioning is client disempowerment or disengagement. When little space is created for clients to take the initiative in the dialogue, they may stop trying and hand over the lead in the conversation to an over-zealous questioner. Sandra and Gina discuss Gina’s experience as the client in the video above, attending to the risk of over-questioning.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, May 15)

What’s in a question?

Animated video

There are many different types of questions, some of which have been developed within different models of counselling. We will introduce a number of these as they are used in various videos. In all cases the specific type of question should be chosen in a purposeful way by the counsellor. This short video illustrates the risks associated with too many why questions. In the context of counselling, a series of why questions might lead the client to feel defensive or to disengage from the conversation.

© Yevgen Yasynskyy & Sandra Collins (2021, May 15)

You might also want to watch out for leading questions, which foreground counsellor perspectives or agendas in a way that can tip the balance of power in the relationship, pose a barrier to client sense of safety or openness, or result in a loss of important information from the client if they follow the counsellor’s conversational lead. Consider the following examples of leading questions and the alternatives that are more client-centred.

| Leading, counsellor-centred questions | Open, client-centred questions |

| How well did this first counselling session go for you? | What worked or didn’t work for you in this first session? |

| Given that most clients benefit from clearly articulating what they hope to attain from the counselling process, what would you say is most important to you? | What is it that you are hoping to gain from our time together? |

| If you found it helpful to talk about your cultural background, should we plan to spend a bit of time doing this each week? | What was it like for you when I invited you to share a bit about your cultural background? |

| I get the sense that the main challenge in the relationship with your spouse is mistrust, correct? | How would you describe the main challenge in the relationship with your spouse, if there is one that stands out more than others? |

| How fast do you move into anger when things start to go awry? | When things start to go awry, how do you respond? |

| I assume you are familiar with the expectations of the university, so how does your choice to cheat serve your best interests? | What was happening for you during that time period that affected your decision-making? |

2. Probing

Probing is similar in intent to questioning but is phrased as a statement rather than a question. For example, you might ask a client: What stands out when you reflect back on that conversation with your brother? Or you might rephrase as a statement: Expand on what most stands out for you when you reflect back on that conversation with your brother. Probing is a useful microskill, because can break up an information-gathering conversation to avoid some of the potential negative outcomes of too many questions (as noted above). Some clients may not respond well to questioning, so probing offers an alternative conversational structure to serve the same purpose.

One of the challenges with probing for new counsellors is that it can sometimes feel a bit too direct and directive. We paused to think critically about the terminology of probing, because we worried it might connote an other-oriented, counsellor-focused approach. The Merriam-Webster (n.d.) thesaurus offers a number of synonyms for probing; our intent in using the word is to invite considering, discovering, and inquiring with a view to promoting a shared understanding of client lived experiences, as opposed to: investigating, unearthing, directing, or examining from a power-over positioning. Using probing effectively requires purposeful creativity to avoid the pitfall of repeating the same verb over and over: Tell me . . ., tell me . . ., please tell me.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

|

Probing: Open consideration of client lived experiences

Animated videos

Watch the following animated video, paying close attention to the ways in which the counsellor uses probing. This is a continuation of the story of George introduced above.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 13)

Notice how George responds to the counsellor’s use of this microskill, supported by her tone of voice and attentive listening.

In this second, partially animated video, Sandra demonstrates creative use of a diversity of verbs as the counsellor (rabbit) as she considers some of the sociocultural context of Lionel’s presenting concern: Lionel has lost his tail.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 14)

For the purpose of becoming proficient in the use of various microskills, it is important to engage in applied practice with a narrow set of skills to increase your comfort level with each one. However you would rarely use them in isolation in an actual counselling session. In counselling conversations, it is most often more effective to follow questioning or probing with paraphrasing what you have heard from the client, reflecting feeling (which we will introduce in Chapter 5) or reflecting meaning (Chapter 6). We introduce the microskills incrementally to encourage your proficiency with them as a foundation for learning to use each of them responsively in your conversations with clients.

Try to have a conversation this week with a friend, family member, or colleague using only questions and probes. Do not try it with a client!. You may find it useful to create a list of verbs to preface your probes (e.g., explain, describe, identity, clarify, consider, list, provide, expand). Take note of the kind of information offered in response to your probes. Pay attention also to nonverbal cues about the efficacy of your use of this communication tool. Debrief with that person about their experience of the conversation.

3. Clarifying

There are times when it is completely appropriate to use questions that are more closed in nature. Clarifying questions often lead logically to a “yes” or “no” answer or to specific information. These are sometimes referred to as closed questions. Clarifying questions can be particularly helpful in the early stages of the counselling process. You’ll notice also that clarifying was used in the questioning microskill video with George as a way for the counsellor to ensure that George was in agreement with the suggested direction for the session:

Counsellor: George, I think it would be helpful for me to understand a bit more about your family history. (Transparency)

Counsellor: Are you comfortable answering a few questions? (Clarifying)

George responded by saying, Sure. I can see how that would be helpful. This short response fits with the purpose of clarifying, which is to invite specific information: in this case a confirmation that the direction of the conversation fits for George.

Although clarifying usually takes the form of a more closed question, clarifying may also be accomplished through more narrowly focused or closed statements: “How many sisters do you have, and how old are they?” versus “Please list your siblings and their ages.”

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Question or statement |

|

|

|

Clarifying: Gathering more specific information

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

The microskill of clarifying is particularly useful during the early stages of counselling when it may be important to gather specific or detailed information from the client in order to position their presenting concerns in context. In the video below Gina draws predominantly on the skill of clarifying to get a better understanding of Sandra’s concerns for her parents during the pandemic. Try to identify one other microskill from Week 2 that Gina also introduces in the conversation.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, February 9)

We will now start combining some of the microskills introduced in this chapter to demonstrate how they might work together to support the counselling process.

Combining microskills: Questioning, probing, and clarifying

Featuring Sandra Collins

The purpose of this video is to assist you to discern among the microskills of questioning, probing, and clarifying. Pause the video after each counsellor verbalization, note the microskill used, then start the video again to verify your response.

© Sandra Collins (2021, January 29)

How successfully were you in identifying each microskill Sandra used? Which ones were more difficult to discern? Review the description of those individual skills to ensure you understand the difference among them. Sandra used questions to demonstrate clarifying in this video. Replay the video to practice clarifying by changing those questions to similarly closed or specific statements.

Both questions and statements can be more closed (e.g., Would you like to take a break now? Remind me how old your daughter is.) or more open (e.g., What would you like to talk about? Describe what that was like for you.). We have distinguished between questioning and probing (more open) and clarifying (more closed) in the descriptions and videos above. Clarifying questions or statements are more closed and lead logically to a “yes,” “no,” or other brief response. Although this microskill can be very useful in inviting clients to share specific details, particularly as part of information gathering in early conversations, overuse of more closed microskills can shut down the dialogue rather than invite elaboration by the client. At times when you are engaged in deepening understanding of client lived experiences, we encourage you to lean towards more open questioning and probing to keep the dialogue client-focused and to encourage in-depth consideration of clients’ presenting concerns.

4. Self-Disclosing

One of strategies we employ in this ebook is the application of metalearning processes: Instead of simply describing a particular principle, we attempt to model it. Reflect on what you have learned about each of us so far through our small self-disclosures. What effect do these stories have on your engagement with the ebook or on the meaningfulness of the ideas? Our self-disclosures have been in the form of short stories related to our work with clients. Often self-disclosure in the context of counselling is a briefer statement directly related to what the client is expressing in the moment. Audet (2018a) identified two forms of counsellor self-disclosure: (a) Nonimmediate self-disclosure in which the counsellor shares elements of their lived experiences as an example, to communication empathy, or to validate client thoughts and feelings; and (b) self-involving disclosures of counsellor thoughts or feelings as they arise during the session in response to the client. Consider the explanation of the microskill of self-disclosing below.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement | Share, intentionally and in a client-centred way, either (a) counsellor personal history or lived experiences, or (b) immediate, in-the-moment reactions (emotions or thoughts). |

|

|

It is important to point out that communicating empathy to a client involves letting them know in a care-filled manner that you hear and understand what they are telling you about their lived experiences. Empathy does not depend on sharing the same lived experiences, and in some cases, attempts to build sameness may be counterproductive to communicating empathy and co-constructing shared understanding. Remember Gina’s practice story in Chapter 2; her decision not to engage in self-disclosing of her own story was based on what she perceived as the best approach to care-filled attending to her client’s needs. She recognized that, in some cases, self-disclosing has the potential to cause damage to the client or to the therapeutic relationship.

As you begin to use self-disclosure in your practice, attend also to differences in cultural norms. Some clients may be much less comfortable with counsellor self-disclosure, because they lean towards positioning healthcare providers as authority figures and have a preference for more professional distance between the client and practitioner. Ultimately self-disclosing, in the context of counselling, must be in service of the client.

Self-disclosing: Nonimmediate and self-involving disclosures

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

As you watch the video below, pay attention to the microskills from Chapter 2 that Sandra reintroduces. Next she draws on both forms of self-disclosure by first sharing immediate, in-the-moment reactions, and then by introducing a short snippet of personal history and experience. Her goal is to validate Gina’s experiences and to communicate empathy.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, February 9)

What additional risks might be associated with self-disclosure? What criteria might you use to discern whether it is appropriate to reveal your thoughts or feelings in-the-moment or to share a piece of your own lived experience with a client? How will you know if your use of self-disclosure has met the criteria of communicating an ethic of care?

Engaging judiciously and purposefully in self-disclosure

Contributed by Leah Beech

Consider this example of self-disclosure with a client in my counselling practice, paying attention to factors that might affect your choice to disclose or not disclose a personal experience.

I was working with a female client in her early thirties who had recently graduated from a professional program that required extensive training, both academic and practical. She was entering the workforce and experiencing significant anxiety, self-criticism, and low motivation. The client discussed comparing herself to colleagues who seemed to be confident, successful, and to have it “all figured out” in terms of their direction in their career. She was not sure yet what she wanted to specialize in within her career and was having such overwhelming anxiety that she questioned whether she had chosen the right profession.

We discussed many therapeutic concepts that she found helpful but at one point, when we were talking about her concern regarding whether she had made the right career decision, I was attempting to explain something about “imposter syndrome.” As I was talking I had the thought that I could explain this better with an example of a similar challenge I had already worked through.

I shared that in the same year I had completed my supervised hours for licensing, I had accepted a job that I quickly discovered was not the right fit for me in terms of the specialization area. I highlighted that this too made me question whether I had selected the right profession, which is extremely discouraging after the time and training I had committed to registering as a psychologist. I noted that my field is quite broad, and similar to my client’s profession, it can take time to find which combination of interest and skill is the right fit. I added that this experience had pushed me to find other employment that I enjoyed more. I normalized how some people know from the beginning what they want to specialize in, while others need to explore, and reassured her that either process is acceptable.

I felt that this disclosure would benefit the client, because there were parallels in our experiences, and she was feeling different from her peers in a negative way. At the end of the session the client shared with me that she had appreciated this self-disclosure, because it validated her experience of not knowing right now, and she was also able to reframe the present as a time to further explore her interests in her profession.

Based on my experience and reading (Hill, Knox, & Pinto-Coelho, 2019; Yalom, 2002), here are few tips for effective use of self-disclosure:

- Position self-disclosure as a relational practice, and assess the potential impact on the therapeutic relationship.

- Use self-disclosure judiciously, purposefully, and minimally to keep the focus client-centred.

- Be clear within yourself about the reasons for self-disclosing.

- Disclose only content that is appropriate to the particular client and to a professional level of intimacy.

- Invite feedback from the client about their experience of therapist self-disclosure (i.e., What is it like for you to hear me share that?)

- Recognize that the ability to self-disclose appropriately does develop with experience, and it is by no means a perfect science.

- Pay attention to the cues, verbal and nonverbal, from clients to discern whether to share with a client.

- Ask yourself this important question: Will this disclosure benefit the client?

- Ensure that the focus remains on the client and that self-disclosure is not about serving your own needs.

- Listen to your gut. If you feel hesitant, this may be a sign that a personal–professional boundary is about to be crossed.

Reflection exercise

- Think about a time you self-disclosed something to a friend, family member, client, or colleague, and it seemed to strengthen your relationship. What was that experience like for you? What gave you confidence that this was the right choice in that moment?

- Now consider a time when self-disclosure did not feel right? What was that like for you? What cues did you notice that made it not feel right? What might you learn from the tips above to enhance your discernment skills?

5. Validating

One of the meanings of the term, validate, is “to recognize, establish, or illustrate the worthiness or legitimacy of” something (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). In the case of counselling, validating is focused on the client’s emotions and sensations, thoughts and beliefs, and other dimensions of their lived experiences. The intent of the microskill of validating is similar to what is referred to in solution-focused therapy by the term, normalizing. Both words serve the purpose of depathologizing client lived experience; however, in applying a lens of cultural responsivity we steer away from language that might infer that there is one standard or norm against which human experience is assessed. It is particularly important from a cultural safety perspective to ensure that you do not engage unintentionally in invalidating by comparing the lived experience or perceptions of your client to dominant cultural norms.

There is a fine line between validating and minimizing. Particular caution is required when clients speak about their experiences of cultural oppression or marginalization. For example, although it may be accurate to say, “Racism has been embedded in Canadian socioeconomic and political institutions for hundreds of years,” a young Asian mother who has just experienced someone spitting in her face on the bus might not find your response validating of her experience. Instead a less broad and more personalized statement may be perceived as more helpful and empathetic: “You are not alone, as a member of the Asian community, in being targeted in this way. I have heard similar stories from other clients.” As noted below validating can take the form of either statement or a question.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement or question |

|

|

|

Validating: To confirm, authenticate, bear out, corroborate, substantiate

Featuring Gina Ko and Lisa Thompson

The process of validating requires the counsellor to position the client’s thoughts, feelings, behaviours, or other aspects of their lived experience in relation to those of other people struggling with similar challenges. In the video below Gina deepens understanding of the challenge that Lisa is facing, and then uses the microskill of validation to invite Lisa to consider the broader context of her experience.

© Gina Ko & Lisa Thompson (2021, April 14)

In the video below we meet up again with Lionel, who has still not found their tail. Notice how the counsellor uses the skill of validation without minimizing Lionel’s experience or comparing it to a particular expectation of what is normal.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 13)

Take a moment to reflect on a time when you felt very alone in your thoughts, feelings, or other aspects of your lived experience. Spend a few moments conjuring up that experience, leaning into what it was like for you. Then write out 3–4 validating statements or questions. Practice repeating each one to yourself, and reflect on how doing this shifts your perception or retrospective experience of that moment in time.

6. Skills Synthesis

The skills synthesis videos in each chapter are designed to demonstrate how you might effectively integrate these microskills in a client–counsellor conversation. We also integrate one or more of the themes related to relational practices or counselling processes into each of these videos, which provide a model for the applied practice activities below.

Informed consent as an iterative conversation

Featuring Sandra and Gina

In the video below Sandra draws on the microskills of self-disclosing, questioning, probing, clarifying, and validating. She also integrates transparency from Chapter 2 to highlight purposefully the process of ongoing informed consent with Gina.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, February 2)

Following the creation of the video, Sandra and Gina recorded their short debrief of this skills practice demonstration. The audio recording is provided below.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

A. Cultural Self-Awareness

We began this chapter by talking about the importance of cultural safety for all clients. Applying a lens of cultural safety to counselling practice requires attention to the social and historical contexts in which client challenges emerge, to culturally oppressive systems and structural barriers to health, and to power imbalances between healthcare practitioners and clients. Fully embracing commitment to cultural safety is possible only through honest engagement in cultural self-reflection. We invite you to complete the activity below to increase your cultural self-awareness of the attitudes, beliefs, worldviews, and values that undergird your views of health and healing, of how challenges emerge, of the relationship of health challenges to cultural identities and social locations, and so on.

Reflect on each element in the diagram below, and ask yourself how your beliefs as values in that area can facilitate or pose barriers to creating a sense of cultural safety for all clients. Stretch yourself to consider potential biases that you may hold about other persons or peoples, being as honest as you can.

Figure 3

Cultural Self-Awareness as a Foundation for Facilitating Cultural Safety

Once you have engaged in critical reflection in each area, make a plan to engage in other learning activities to mitigate any biases you discover.

B. Enlisting Your Own Story

As you continue to develop your own story this week, consider how your personal experiences within healthcare settings influenced your assumptions and biases (from the activity above) or positioned you to feel unsafe in seeking out support for the presenting concern you have identified. Reflect on the principles, concepts, and practices in this chapter that seem most applicable to your lived experiences.

C. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Macey’s story: Part 3

As you listen to the continuation of the story of Macey this week, attend to what you learn about her cultural context. Consider what your next steps might be as her counsellor.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, February 18)

As you reflect on the continuation of Macey’s story and the themes introduced in this chapter, watch this video in which Gina Ko introduces a particular form of reflecting team practice. Attend to each of the prompts that Gina provides. You may want to form a small group of peers to engage in this activity, so you can share your ideas about feedback you might provide to Macey with each other.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 15)

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

The primary focus of the applied practice activities below is on the microskills introduced in this chapter. However we will also revisit the microskills of listening and attending actively, paraphrasing, and providing transparency (from Chapter 2) to reinforce your learning and to demonstrate how these microskills can be integrated with those introduced in this chapter.

Participating in the creation of this ebook provided an opportunity for me to step back and reflect on what I have learned from teaching counselling microskills across a number of decades. As a graduate student I was taught, and then initially followed in my own teaching, a strongly educational psychology model in which counselling microskills were positioned as value-neutral tools for enhancing the counsellor’s ability to structure and effectively engage in conversations with clients. This decontextualized approach failed to take into account client context, history, and lived experience. In those early days there was little reflection on the impact of culture or social location on client–counselling relationships.

Attention to culture and social justice has strengthened considerably in the last couple of decades, and we hope that this ebook adds to these tides of change. I would now argue that nothing we do as counsellors or as counsellor educators is value neutral. We argue in this ebook that counsellors must act with intention, responsibility, and cultural accountability from the moment they set up a practice, through their first encounters with clients, and continuing through until they negotiate endings.

This sense of relational accountability also applies to the teaching of microskills and techniques. Just like clients, counselling students are global citizens who come from all parts of the world. You come as learners with your unique intersectional positioning of age, ability, Indigeneity, ethnicity, religion or spirituality, social class, gender, sexuality, and so on. You have a history (individual, familial, community , national) with healthcare systems and practitioners that is grounded in your social location. We have positioned cultural safety in this chapter as a foundation for beginning to talk with clients about their presenting concerns. However, it is equally important for you to attend to cultural safety throughout the applied practice activities in this ebook. Coming together as learning partners to talk about real issues in your lives involves trust and risk-taking. You do not know about your partner’s lived experiences, and it is important to hold this contextualized lens of cultural safety as you engage with each other.

Sandra

A. Responsive Microskills

In these activities we invite you to draw on a combination of skills from Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 and to apply them in a way that supports particular relational practices or counselling processes. If you struggle with a particular activity, break the conversation down into smaller chucks with fewer skills. Then try again once you feel more confident and comfortable with each chunk. You may want to print out the applied practice activities before you begin your practice session, so they are readily available.

1. Cultural self-awareness and self-disclosure

(20 minutes)

Preparation

Take a moment to reflect on the cultural self-awareness activity in the Reflective Practice section earlier in the chapter. Drawing on your evolving consciousness as a cultural being, identify what you are most anxious about as you work on developing culturally safer and responsive relationships with all clients. Review the two different types of self-disclosure in preparation for this activity.

Skills practice

For this activity assume the person in the role of client is seeing a therapist as part of their personal–professional development. Remember the person in the role of counsellor should do the recording (5–6 minutes each).

- Client: Talk very briefly about what you are most anxious about in terms of developing culturally safer and responsive relationships with all clients.

- Counsellor: Use questioning to find out more about what the client is experiencing.

- Client: Respond in whatever way feels natural and genuine.

- Counsellor: Use paraphrasing to communicate that you are listening along with either minimal encouragers or body language (Chapter 2).

- Counsellor: Try out the first form of self-disclosing (i.e., personal examples or experiences) to build connection and mutual empathy, drawing on your evolving cultural self-awareness.

- Client: Respond in whatever way feels natural and genuine.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How did adding the microskill of questioning enhance your ability to gather information about the client’s lived experience (compared to the practice activities in Chapter 2)?

- What was it like to offer and receive self-disclosure as counsellor and client?

- What principles might you use to ensure that self-disclosing always remains client-centred?

2. Building cultural safety

(40 minutes)

Preparation

Reeves (2018) invited counsellors to share information about their cultural identities and social locations, including acknowledgement of their settler/colonialist status (if applicable) when working with Indigenous clients. Dr. Gunderson, in her video earlier in the chapter, encouraged you to become familiar with the Indigenous territories on which you live and work by checking out the Native Land website. Examples of our positioning as authors within the colonial context of Turtle Island are provided in the ebook Acknowledgements.

Although cultural safety emerged as a relational practice through the work of Indigenous theorists and practitioners, all clients have a right to a culturally safe space. In preparation for this activity take time to reflect on the ways in which other aspects of your cultural identities position you with privilege or disprivilege in society, including the inherent power in the client–counsellor relationship.

You may want to review the audio example below the skills practice description as you prepare for this practice activity.

Skills practice

Take a few minutes to discuss with your partner your position within the colonial relationship (as an Indigenous or non-Indigenous person) as well as other dimensions of your social locations that afford you power and privilege or position you with less power and privilege. Then complete one round of skills practice each, drawing on your actual social locations (5–6 minutes). Next you may want to repeat this practice activity several times with the client role-playing different cultural identities or social locations. Notice what you change in your approach to different clients.

- Client: Behave as if you are encountering the counsellor for the first time. Briefly introduce a presenting concern without making obvious connections to your social location.

- Counsellor: Start by providing transparency (Chapter 2) to introduce the conversation. Then use self-disclosing (of counsellor personal history or lived experiences) to share relevant dimensions of your cultural identities and social location.

- Counsellor: Practice using silence to give the client a chance to respond if they choose.

- Client: Respond in whatever way feels natural and genuine (or reflects the role you are assuming).

- Counsellor: If your partner identifies as Indigenous (personally or in role-play), offer a brief territorial acknowledgement (providing transparency).

- Client: Respond in whatever way feels natural and genuine (or reflects the role you are assuming).

- Counsellor: Use the skills of providing transparency and self-disclosing to explicitly name your power and privilege.

- Counsellor: Practice using clarifying (do you . . . would you . . . does this . . .) to ensure that client understanding or to check if the client has questions for you.

The audio below provides examples of what a counsellor’s use of transparency and self-disclosure might sound like in this context [PDF version]. Remember it is important to personalize your approach and to adapt it in response to the client you are working with.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How comfortable were you sharing your relative privilege with clients as a way to create cultural safety? Reflect critically together on the source(s) of any discomfort that arose.

- What challenges did you encounter using the microskills of transparency and self-disclosure purposefully to create cultural safety?

- What additional learning opportunities or skills practice activities might support you to gain proficiency and increase your comfort?

3. Cultural humility

(30 minutes)

Preparation

Please plan ahead to introduce a topic, in your role as client, that you feel passionate about, but that you also see as somewhat controversial (i.e., some people may not relate to, or agree with, your perspective). If you are really stuck, you can make something up; however, your partner will benefit from your genuineness, whenever possible, in the skills practice.

Skills practice

Each take a turn in the counsellor and client roles below (5–6 minutes each).

- Client: Introduce the topic you want to talk about.

- Counsellor:

- Use questioning and probing to examine the topic openly with the client.

- Attempt to suspend judgement and express cultural curiosity.

- Try to stick to questions that start with what, when, why, how (more open), rather than can you, do you, have you (more closed).

- Client: Respond in a way that is genuine, but passionate or provocative.

- Counsellor:

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback to each other about the degree to which your use of microskills was more open than closed.

- Remember to state your feedback in a way that is descriptive, positive, specific, and immediate. This is more encouraging and motivating than identifying the one or two things that did not go as well.

- For example you might say, “You used both questioning and probing. All but one of your microskills was more open” or “From the client perspective, I found this question . . . and this probe . . . particularly helpful in encouraging me to . . .”.

- Identify one or two client presenting concerns that you may be uncomfortable talking about. Brainstorm ways to lean into these conversations with genuine care and cultural humility.

4. Gathering information and informed consent

(50 minutes)

Preparation

Consider the brief overview (below) of the types of information you may invite clients to share as part of the process of gathering information [PDF version]. The topics you focus on will depend on their relevance to the client’s presenting concern(s), the context and purpose of the counselling process (including organizational policies and practices), and most importantly, the client’s consent to discuss each domain.

- Demographic information: name, age, pronouns, gender/gender identity, ethnicity or Indigeneity, socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, marital status, religion or spirituality, nationality, and languages spoken.

- Reasons for initiating counselling: symptoms or challenges; affective, behavioural, cognitive, or interpersonal experiences; impacts on sense of well-being.

- Current situation: severity of the challenges, resiliency factors (i.e., strengths, social supports, resources, competencies). You may want to discuss changes in functioning as a result of their presenting concern(s).

- Previous counselling experiences: reasons for seeking out counselling in the past; what worked or didn’t work for them; results of previous assessments (including diagnoses and their reactions to describing their symptoms in that way); past and current medications related to mental and emotional challenges.

- Birth and developmental history: circumstances of birth and delivery; sense of security with significant caregivers; recollection of early developmental milestones or challenges encountered during childhood and adolescence.

- Family history: value placed on, and definition of, family; composition of family of origin and current family, including chosen family; biopsychosocial challenges faced by family members (e.g., developmental, learning, medical, emotional, cognitive, psychological) currently or in the past.

- Sociocultural context: contextual factors impacting the presenting concern(s); affiliation to cultural communities, relationship to dominant population; experiences of cultural oppression; systemic barriers or facilitators.

- Health history: significant injuries, surgeries, conditions, or illnesses; medications taken for past and current conditions; current health status and desired health status.

- Educational and work background: personal and cultural value placed on education and work; educational and work history; personal and interpersonal strengths and challenges; current educational or work setting; degree of satisfaction.

Skills practice

Take turns in the role of counsellor, choosing one of the information gathering domains to discuss (6–8 minutes each). You may discuss your partner’s presenting concern in advance, so that you can select appropriate areas of inquiry. Remember to avoid topics that are deeply personal or troubling.

- Client: Introduce a presenting concern that offers sufficient breadth and depth for this conversation.

- Counsellor:

- Introduce the potential area of focus, providing a clear explanation for why it may be meaningful to understanding the client presenting concern (providing transparency).

- In your first round as counsellor, practice dismantling client and counsellor preconceptions that counsellors have a right to this information (rather than being privileged and entrusted with it) by using transparency to inform the client of their right to say, “No,” to any question you pose. Then use the microskill of clarifying to ensure they feel comfortable proceeding.

- Client: Feel free to raise concerns or questions that arise from the counsellor’s initial overview of information gathering and informed consent.

- Counsellor: Focus exclusively on questioning (more open) and clarifying (more closed) to deepen shared understanding of the client’s presenting concern.

Switch roles and repeat with a different area of focus for information gathering. Once you have completed a round each, choose another information domain (each) and try out the microskills below (6–8 minutes each).

- Counsellor:

- Briefly remind the client about the ongoing process of informed consent (providing transparency), and explicitly invite their consent (clarifying).

- Switch to probing (more open) to deepen shared understanding of the client’s presenting concern.

- Introduce paraphrasing to acknowledge the client’s thoughts, feelings, or experiences.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback on the counsellor’s use of various microskills, focusing on their sensitivity (ethic of care, cultural safety) and responsivity (relevance for this particular client with this specific presenting concern).

- Reflect on the pros and cons of more open versus more closed skills for information-gathering.

- Discuss briefly how you might actively respect cultural differences in privacy norms.

5. Conceptualizing client lived experiences

(40 minutes)

Move into a more open discussion of client lived experiences for this next practice activity (6–7 minutes per person per round). Continue to talk about the presenting concerns from the previous activity.

Skills practice

Round 1

- Counsellor:

- Use a combination of questioning and probing to continue open conversation about the client’s presenting concern.

- Respond with minimal encouragers and paraphrases to encourage dialogue and communicate active attending.

- Client: Respond in whatever way feels natural and genuine.

- Counsellor: Introduce the second form of self-disclosing (i.e., your reactions in the moment: thoughts, feelings, embodied responses) to express empathy with client experiences and foster connection.

Round 2

- Counsellor:

- Use a combination of questioning and probing to continue open conversation about the client’s presenting concern.

- Focus on nonverbal attending (i.e., silence, body language, active listening).

- Client: Provide an opening in your responses that suggests a need for validation.

- Counsellor: Watch for opportunities to practice the skill of validating to reduce the client’s sense of isolation or to counter feelings of shame, stigmatization, or self-doubt.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Reflect critically on your purposeful and intentional use of various microskills. How might you discern what skill will be most effective and responsive to client needs in-the-moment?

- Consider the differences between self-disclosing and validating from both the counsellor and client perspectives. What are the benefits and potential challenges for each one?

REFERENCES

Audet, B. (2018a). Navigating the power of ageism: A single session. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 506–530). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association. (2016). Call to action: Urgent need for improved Indigenous mental health services in Canada. https://www.ccpa-accp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Issue-Paper-2-EN.pdf

Chew, J. (2018). Finding one’s voice: A feminist perspective on internalized oppression. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 255–258). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018a). Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 51–114). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018b). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: A foundation for professional identity. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 343–403). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018c). Endings as beginnings: Empowering client and counsellor continuing competency development. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 852–867). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018d). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Feinstein, R., Heiman, N., & Yager, J. (2015). Common factors affecting psychotherapy outcomes: Some implications for teaching psychotherapy. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 21(3), 180–189. http://www.practicalpsychiatry.com

Fellner, K., John, R., & Cottell, S. (2016). Counselling Indigenous peoples in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 123–147). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

First Nations Health Authority. (n.d.). Definitions. http://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Cultural-Safety-and-Humility-Definitions.pdf

Hill, C. E., Knox, S., & Pinto-Coelho, K. G. (2019). Self-disclosure and immediacy. In J. C. Norcross & M. J. Lambert (Eds.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Volume 1: Evidence-Based Therapist Contributions (3rd ed.; pp. 379–420). Oxford University Press.

Houshmand, S., Spanierman, L. B., & De Stephano, J. (2017). Racial microaggressions: A primer with implications for counseling practice. International Journal of Advanced Counselling, 39, 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-017-9292-0

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Validate. Merriam-Webster.com thesaurus. Retrieved April 13, 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Northern Health Indigenous Health. (2021). Cultural Safety: Supporting increased cultural competency and safety throughout Northern Health. https://www.indigenoushealthnh.ca/cultural-safety

Nuttgens, S., Anderson, M., & Brown, E. (2021). Teaching counselling amidst the evolving evidentiary landscape. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 55(1), 51–73. https://doi.org/10.47634/cjcp.v55i1.70419

Nuttgens, S., & Smith, D. (2016). Ethical and legal issues in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling and Psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 13–33). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Parrow, K. K., Sommers-Flanagan, J., Cova, J. S., & Lungu, H. (2019). Evidence-based relationship factors: A new focus for mental health counseling research, practice, and training. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.4.04

Poster, M. F. (2019). Review of “common factors,” personal reflections, and introduction of the shaving brush model of integrated psychotherapies, Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 25(5), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRA.0000000000000418

Reeves, A. (2018). Using a cultural safety lens in therapy with Indigenous clients. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 450–455). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Robinson, B., Lehr, R., & Severi, S. (2015). Informed consent: Establishing an ethically and legally congruent foundation for the counselling relationship. In L. Martin, B. Shepard, & R. Lehr (Eds.), Canadian counselling and psychotherapy experience: Ethics-based issues and cases (pp. 25–74). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Shah, C. P., & Reeves, A. (2015). The Aboriginal cultural safety initiative: An innovative health sciences curriculum in Ontario colleges and universities. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 10(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijih.102201514388