Chapter 6 Collaborating in Meaning-Making

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Anita Girvan, Ivana Djuraskovic, and Simon Nuttgens

In this chapter we shift our focus to the cognitive domain, inviting exploration of clients’ self-talk, beliefs, values, and assumptions. We argue that how we think about client challenges as counsellors, and how clients come to view their lived experiences, cannot be fully understood without appreciation of the sociocultural contexts of meaning-making. We also argue that clients and counsellors actively engage further in meaning-making within their conversational exchanges, often co-creating new perspectives, useful metaphors, and deeper understandings. Recall Figure 1 (below, which first appeared in the Introduction’s conceptual overview) that emphasized the complex and multilayered nature of client–counsellor communication. We invite you in this chapter to consider your own stories and the stories of clients from both idiosyncratic (person-centred) and contextualized (socioculturally embedded) lenses.

Figure 1

Contextualized, Relational, Growth-Fostering Communication

Figure 2

Chapter 6 Overview

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

A. Sociocultural Construction of Meaning

We assume a social constructivist lens on the counselling process through which ways of knowing and being are embedded in relationships and sociocultural contexts (Bava et al., 2018). The meanings that human beings make of their lived experiences are inextricably intertwined with the contexts of their lives at the microlevel (i.e., individuals, significant others, families), mesolevel (i.e., schools, organizations, or communities), and macrolevel (i.e., broader social, economic, and political systems). This also means that meaning-making is fluid and changes over time and across context, evolving through interactions with other people, contexts, and systems (Bava et al., 2018; Combs & Freedman, 2018; Cook, 2018; Paré, 2013). These assumptions about meaning-making have significant influence on how we, as authors of this ebook, approach the counselling process, in particular the co-constructing meaning with clients.

Critically analyze this image of someone peeling the layers of an onion, as a metaphor for creating meaning in the context of the client–counsellor relationship. How might this image fit or not fit with a social constructionist perspective on meaning-making?

Come up with an alternative image to capture your perspective on how shared understanding is actively co-constructed between counsellor and client. Consider the implications of approaching your work with clients by foregrounding one or the other of these images.

1. Culture and Social Location

One potential risk of applying the lens of cultural and social location to each of the concepts, principles, and practices in this ebook is that we send the message that client challenges are always centred in, or directly influenced by, their cultural identities and social locations. The latter may lead counsellors to position culture as the problem rather than focusing on the ways in which cultural and social contexts can increase client vulnerability to particular challenges. Collins (2018a) warned against cultural hyperconsciousness, positioning this at the opposite end of the spectrum from an equally problematic lack of awareness of, or attention to, culture. She encouraged a balanced position of cultural consciousness in which counsellors continuously assess, in a tentative and client-centred way, the salience of cultural and social location to client lived experiences.

Collins’s (2018a) position stems from the assumption that psychological concepts, principles, and practices are also socially constructed, most often in contexts dominated by eurocentric worldviews. Paré (2013) and Gergen (2015) spoke of the importance of holding tentatively to theoretical and applied practice principles, even those that define the professions of counselling and psychology, to avoid treating them as if they are truths rather than sociocultural assumptions about reality. When clients and counsellors come together in counselling, each brings socially constructed lenses on culture, human nature, problems, preferred outcomes, and change processes (Paré, 2013; Socholotiuk et al., 2016).

As we move into talking about meaning-making with clients in this chapter, it is important to consider the broader influences on how clients view themselves, their relationships to others, and their positioning within the world around them. In this first video Anita Garvin, whose research and writing focuses on cultural-ecological studies, invites your consideration of the ways in which cultural metaphors are constructed and the power they hold in defining how human beings understand themselves, relate to each other, and make meaning of their worlds. The metaphors that are chosen, as well as the social location of those who have the power to choose them, can have significant impacts on the health and well-being of persons and peoples.

by Anita Girvan (in conversation with Sandra Collins)

In this video Anita introduces metaphors as a way of mediating for us and composing worlds, drawing on current metaphors related to the COVID-19 pandemic as points of illustration. Consider critically the ways in which the war metaphor, for example, functions to both mobilize action and also carries over meanings that have serious negative impacts on particular people and peoples.

© Anita Girvan (2021, May 24)

Questions and prompts for reflection:

- Consider critically Anita’s reflections on the metaphor of “client” as it relates to the ways in which you engage with, and position yourself relative to, those you work with in counselling.

- In what other ways might the term, client, cause you to attend to certain relational practices while you miss or invisibilize others?

- Consider the communities to which we offer services as counsellors, and reflect on Anita’s question: Is this the way in which communities themselves would cast the kind of relationship you are having?

- What are the implications of counsellors, clients, and service communities holding different perspectives on the relationships between them?

- Reflect on the metaphors introduced in this ebook, for example, the central metaphor of relational practices. Consider Anita’s question: How does each metaphor function to a create a path toward a relationship between the practitioner and the client?

- Finally identify a few of your favourite or most influential counselling metaphors (e.g., self-actualization, re-storying, blank slate). What are the implications of approaching clients through the lenses created by those metaphors?

To see more of Anita’s work check out her contribution to the book, Sick of the system: Why the COVID-19 recovery must be revolutionary or the YouTube video, Sick of the system interview.

As authors of this ebook who have observed the dramatic events of the past year, we feel an ethical and moral obligation to call attention to the ways in which emergent, socioculturally constructed metaphors are significantly impacting the health and well-being of many persons and peoples in Canada and around the world. Paré (2013, p. 428) defined a narrative as “a web of meanings in that it brings continuity and coherence to what otherwise can be experienced as discontinuous and discrete events.” In our role as counsellors we actively engaging in meaning-making around client stories. These stories can shape not only how clients see the world, but how they see themselves. From a social constructivist perspective even one’s sense of self is socially constructed, and language, which always includes sociocultural metaphors, has a significant influence on the construction of clients’ sense of identity (Collins, 2018b; Combs & Freedman, 2018; Paré, 2013). As Anita noted in her video on the importance of cultural metaphors, the broader sociocultural discourses may be life-expanding or they may be life-limiting. The implications for counselling are substantive. As counsellors we all have a responsibility to examine critically our adoption, often without critical awareness, of life-limiting metaphors that have the possibility of causing harm to clients. We also have the opportunity to collaborate with clients to co-create or draw attention to life- and health-affirming metaphors.

Sociocultural metaphors and anti-Asian racism: Inviting forward anti-racism lenses

by Gina Ko

In this video Gina speaks openly of her experiences as a Chinese Canada woman, as well as the experiences of members of her family, community, and client population, picking up on the war on COVID-19 metaphors that Anita critiqued in her video. Consider carefully the importance of language use as you listen to Gina’s story.

© Gina Ko (2021, May 11)

Drawing on Gina’s personal and professional stories in this video, consider the following questions for reflection:

- How might changing the prevalent cultural metaphors to foreground anti-racism and Asian pride offer opportunities for life-enhancing meaning-making at personal, community, and societal levels?

- What roles might you assume in shaping the cultural metaphors that gain traction in society, with a view to creating safety and supporting the dignity of all persons and peoples?

- How might such metaphors seep into your meaning-making conversations with clients, even inadvertently, and what are the implications of the metaphors that you do embrace?

- How might you engage clients in shining the spotlight on existing, or on co-constructing new, life- and health-enhancing metaphors?

For additional information see Ko (2014) in the reference list.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

A. Conceptualizing Client Lived Experiences

1. Understanding Thoughts and Beliefs

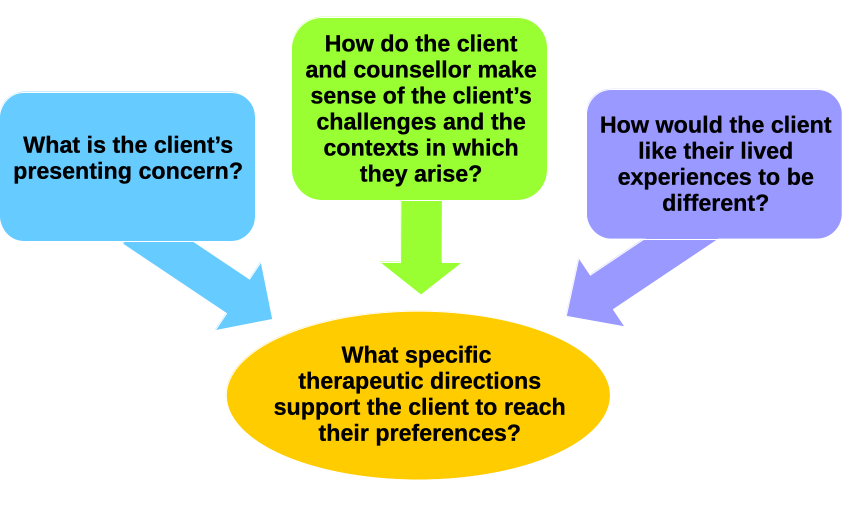

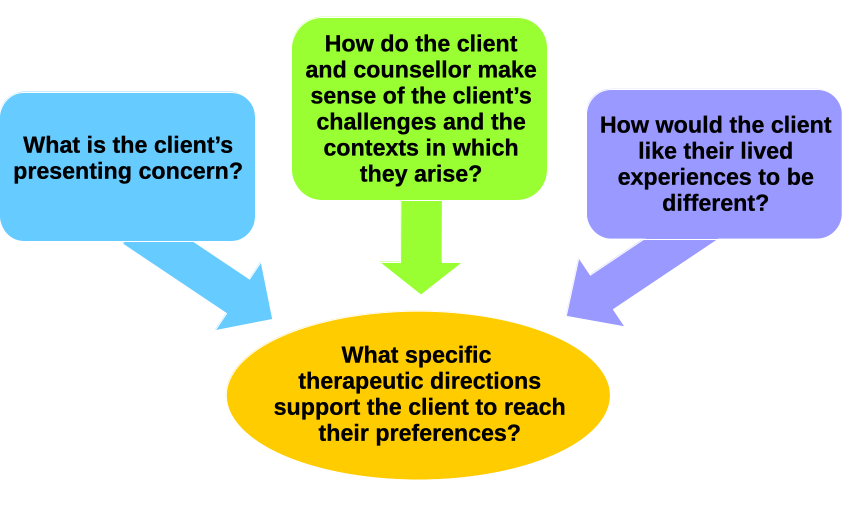

In this chapter we continue to explore on the second question in Figure 3: How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they occur? However, we shift the focus from exploring client affect and embodiment to inviting meaning-making related to client thoughts and beliefs.

Figure 3

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

This image is described in the audio below.

Moving into the exploration of client challenges within the cognitive domain opens the door to more depth and breadth in co-constructive collaboration between counsellors and clients. In many ways it is in the meeting up of client and counsellor thoughts, beliefs, assumptions, and values that worldviews come into play most substantively.

B. Collaborating in Meaning-Making

1. Fostering Constructive Collaboration

Paré (2013) used the term, constructive collaboration, to emphasize the importance of shared meaning-making between counsellor and client. There is double meaning implied by this term: (a) purposeful and change-focused collaboration, and (b) co-creative meaning-making between counsellor and client. Although we caution you in this ebook not to leap into generating solutions to the challenges client present, the process of constructive collaboration begins with your first encounter with clients, and it has significant influence on the efficacy of the counselling process in supporting clients to reach their preferred outcomes. For some clients, the process of working with the counsellor collaboratively to co-create a comprehensive description of the challenges they are facing may give them everything they need to enact the changes they desire. The process of constructive collaboration in meaning-making between counsellor and client also shifts the power dynamics within the client–counsellor relationship from therapist as expert in a power-over position to therapist as co-collaborator with the client as expert on their lived experiences (Bava et al., 2018).

2. Co-Constructing Meaning

We argue that meaning is generated within the counselling dialogue, rather than independently in the minds of counsellor and client. Recall the image of peeling an onion earlier in the chapter. Meaning is not something that is hidden under layers of client thinking or experience, waiting to be discovered by the counsellor. In fact, counsellor and client could be looking at exactly the same thing and derive from it very different meanings. Neither is the goal of counselling simply to transmit information to the client or to receive information from the client; instead, the intent is to create new meaning together. We invite you to embrace a collaborative approach to counselling that capitalizes on the power of the co-construction of meaning through intentional conversations. You are invited to work with, rather than on, your clients and to view the counselling process as counsellor and client “constructing meaning sentence-by-sentence, glance-by-glance, heartbeat-by-heartbeat” (Paré, 2013, p. 23).

From a postmodern and constructivist perspective, there are multiple versions of reality, and the counsellor and client actively co-construct a meaningful reality within the counselling conversation for the purpose of supporting clients to move towards their preferred outcomes (Paré, 2013; Paré & Sutherland, 2016). Counsellors do not simply set out to discover what the client’s story is; rather, they actively contribute to client experience through the co-construction of meaning.

A learning story: Getting it right!

by Simon Nuttgens

Listen to the audio story below as Simon reflects on a difficult learning experience as a developing counsellor.

This transcript provides access to the audio content in pdf format.

Reflections:

- Imagine yourself in Simon’s position as a new counsellor excited about a sudden insight into the challenge your client is facing. What relational principles or practices introduced so far might prevent you from engaging in a similar misstep.

- Reflect critically on the difference between foregrounding your own insights and coming to a place of shared understanding in collaboration with clients.

- Identify your growing edges, and consider which ones you might need to proceed around with caution as you move into relationships with clients with the intention of fostering client-centred, collaborative conversations.

3. Engaging Cultural Metaphors

Metaphors are figures of speech that offer an indirect understanding of an idea by offering up a word or phrase in its place and implying a resemblance or correspondence between them (Merriam-Webster dictionary, n.d.). Their linguistic function is to organize and make meaning of experiences, both internal (i.e., thoughts and feelings) and external (i.e., behaviour, relationships).

How metaphors shape the way you see the world

As an orientation to the pervasive influence of metaphors on human experience and relationships, watch this short video from BBC Ideas.

© BBC Ideas (2020, August 14)

The use of metaphor is common is a wide range of approaches to counselling, and it is particularly useful in the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences. Even when our specific approach does not foreground the use of metaphors, we would argue that they come into play throughout our conversations with clients.

Metaphors as tools for shared meaning-making

by Anita Girvan (in conversation with Sandra Collins)

In this second video Anita reflects on the ways in which metaphors emerge and sometimes proliferate in moments of perceived novelty, drawing on the example of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clients most often come to counselling in times of novelty; that is, when they encounter an experience, in themselves or in relation to others, for which they do not have pre-existing tools. Consider the ways in which this sense of novelty opens up possibilities for shared meaning-making between counsellor and client.

© Anita Girvan (2021, May 24)

Questions for reflection:

- In what ways does the metaphor of way-finding provide a useful framework for the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences?

- What role do metaphors play in your discussions with clients? To what degree are you double-listening to what is said and creating room for retrieving affirmative metaphors in their descriptions?

- What role is there for making metaphors explicit in client–counsellor conversations?

- How might metaphors function to act upon the client’s world in a way that is world-composing or world-making?

Metaphors can be either counsellor-generated or client-generated (Wagener, 2017). Clients, for example, may speak of a thorn in their side, a light at the end of the tunnel, or cloud over their heads. None of these are literal descriptions of experience; instead, they are symbolic references to that experience that help them make meaning of their thoughts, feelings, behaviours, relationships, and so on. Counsellor-generated metaphors can be useful tools for describing psychological concepts or practices in lay language, making them more accessible to clients (Killick et al., 2016). However, Bava and colleagues (2018) caution against counsellor-centred metaphors of client experience, noting that counsellors tend to fill in gaps or missing pieces in client stories with interpretations or insights from their favoured theoretical models incline. They may also fill in theses gaps with knowledge embedded in their own cultural worldviews.

Drawing on cultural metaphors in the co-construction of meaning

by Ivana Djuraskovic

Ivana starts this video off by talking about the metaphor of a green dragon used as a way for women in Bosnia to talk about the horrors of genocide with each other by providing a bridge to speak of the unspeakable. Attend to the ways in which cultural metaphors enhance communication if counsellors are willing to take the time to listen deeply and to invite forward shared understanding.

© Ivana Djuraskovic (2021, April 25)

Reflect on the stories Ivana shares from her own experiences and her work with refugees for whom cultural metaphors are commonly used to carry shared meaning.

- Think back to the themes of cultural safety (Chapter 3) and trauma-informed practice (Chapter 4). In what ways might honouring cultural metaphors support these relational practices?

- What are the risks of applying a literal, diagnostic, or pathologizing lens to client stories without fully exploring cultural metaphors?

- How might you open up space to listen to underlying meaning, rather than jumping to conclusions when you encounter stories that are outside of your understanding or comfort zone?

- There is great beauty and opportunity in language when we invite forward metaphor and other creative, culturally responsive ways of describing experience. Take a few minutes to reflect on the cultural metaphors that add meaning and colour to your conversations with friends and family. How would meaning-making be challenged if you were stripped of those shared images or figures of speech.

As we move into exploring specific microskills for enhancing shared understanding of client thoughts and beliefs, pay attention to opportunities to optimize the use of culturally-responsive, client-generative metaphors.

Becoming a metaphor miner (Catch the metaphor? Prefer a different one?)

by Anita Girvan

- Make a list of all the metaphors you hear (these include the simplest kinds of metaphors like “I’m feeling up/down/blue.”

- Take one of the metaphors you have heard/read, and think critically about how it is orienting you to think about an issue, relationship, or phenomenon. For example:

- If you listen to COVID-19 news coverage, you will hear the war against COVID metaphor organizing responses as well as other metaphors (e.g. lockdown, bubble).

- What are the pros and cons of that metaphor as a wayfinding tool? What does it make visible, thinkable, doable, and what does it leave out?

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

The Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary provides a quick reference to each of the microskills and techniques introduced in this chapter.

A. Microskills

1. Reflecting Meaning

One of the primary counselling microskills that will enable you to co-construct meaning in your dialogue with clients is reflecting meaning. It allows you to communicate to the client what you have noted in the conversation as important or meaningful to them and to offer them an opportunity to further clarify or co-create shared meaning.

When you are really listening to a client, you are able to pick up the meaning behind their words. You may draw on your intuition, your theoretical framework, your knowledge of the presenting concern, your cultural awareness, or other aspects of your own personal or professional experience to make gentle inferences about what is going on for the client or what meaning the client attaches to particular statements or experiences. You might say something like: You value loyalty in your friendships, You are struggling to make sense of what happened in that situation in the absence of feedback from your colleague, or Work is very central to your sense of worth and self-esteem. These are defined as meaning reflects only if you are adding new layers of meaning or inferences that were not explicitly stated by the client. If you simply reword what the client has already said, that is simply paraphrasing.

One of the important things to recognize about meaning reflects is that they are generated by the counsellor, and in some cases, they may actually be counsellor misperceptions of client meaning. One of the functions of a meaning reflect is to check out those perceptions with the client and allow the client an opportunity to clarify, to disagree, or to confirm the inferences you are making. It is important, therefore, to present your meaning reflects respectfully and tentatively. You may find it useful to use prefaces, such as: It sounds like, I have a sense that, or I am hearing . Each of these phrases communicates to your client that you are offering up a possible understanding for their consideration. On the other hand, overuse of these prefaces may indicate to the client that you are unsure about your own listening skills or lack confidence in the interaction. Finding a balance and attending to client nonverbal feedback is important.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

Client: It’s been a long time since I felt confident enough to put myself out there.

|

In some models the microskill of interpretation takes the place of reflecting meaning. Although there are similarities in these skills in that in both the counsellor offers up possibilities for new meanings for the client’s consideration, the term interpretation has the potential to be more counsellor-centred than client-centred. Interpretation typically involves explaining or telling someone the meaning of something (Merriam-Webster, n.d.). Reflecting meaning is intended to be much more closely aligned with the client’s perspective, supporting new understanding on the part of the client and counsellor so they can share meaning-making, rather than foregrounding counsellor insights.

Reflecting meaning

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

Notice how Gina starts by drawing on microskills from previous chapters to draw out a sense of the challenge that Sandra is facing, so that she has enough information from Sandra to use the microskill of reflecting meaning. Pause the video after each counsellor verbalization to practice identifying these skills.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, May 2)

What criteria might you use to distinguish between paraphrasing and reflecting meaning? What did you notice about Gina’s reflecting meaning responses that helped move the conversation forward toward shared understanding of Sandra’s thoughts, beliefs, and values.

Reflecting meaning

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this next video Gina introduces a counselling topic, the meaning of life, that opens the door for Sandra to focus on shared meaning-making. Notice how Sandra integrates microskills from previous weeks, with a particular focus on reflecting meaning.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 16)

Notice that Sandra keeps the dialogue focused on Gina’s values and beliefs. Sandra uses questioning periodically to get a sense of Gina’s priorities, but most of the conversation is carried forward by reflecting back to Gina what she is hearing about Gina’s meaning-making.

Imagine how the conversation might have been different if Sandra’s first question had been, What emotional reaction do you have when you think about this your experience? Look for some other places in the video where Sandra could have picked up on cues about affective experience in what Gina was saying. There is no right or wrong domain focus in these conversations. However, by carrying the same themes forward across several chapters, we hope to model the importance of in-depth and multidimensional exploration of clients’ presenting concerns. Ignoring one domain of experience can result in an incomplete picture of what the client is experiencing, which then forecloses on possibilities for envisioning change.

Experience-Near Responses

The key to effectively reflecting meaning is to add new language to support shared meaning-making. However, the counsellor’s contribution must be experience-near (i.e., language that captures the client’s meaning, intention, values, and feelings) (White, 2005). It is essential to offer up language that the client can relate to and that deepens the shared understanding of the client’s experiences. In some cases this might mean pulling back from the great “insight” that suddenly hits you (recall Simon’s story from earlier in the chapter) to use language that more closely aligns with where the client is at in-the-moment. Paré (2013) contrasts inferences that add new meaning but remain close enough to what the client has said to resonate with them (i.e., experience-near) with those that are experience-distant responses (i.e., outside of the client’s comfort zone or current understanding of experience). Experience-distant responses are more likely to fall flat, to not be picked up by the client, or to be expressly rejected. Often, missing the mark is a sign to the counsellor to listen more carefully and to set aside any preconceptions or assumptions.

Generating experience-near responses is also applicable to reflecting feeling (Chapter 5) and summarizing and co-constructing language (below). These all involve inference-making on the part of the counsellor. Not including any inference at all results in paraphrasing (instead of reflecting) or an agenda instead of a thematic summary. In both cases, the counsellor has missed opportunities to engage the client in constructive collaboration and shared meaning-making. However, making inferences that are too far outside the client’s frame of references or that are disconnected from the client’s experience is also problematic.

Many examples of experience-near responses, those that resonate meaningfully with the client, have been provided in the videos in this chapter. The video below gives you a glimpse into what experience-distance responses might be like.

Experience-near versus experience-distant responses

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

Sandra starts this conversation with Gina by demonstrating experience-near responses in her reflecting of meaning. Attend to where you think she has gone off-track in shifting into experience-distance responses.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 20)

Notice that Sandra’s first attempt at experience-distance responding—”You are not good enough”—unexpectedly resonates with Gina. Then the next few meaning reflects clearly fall short. In the video below, Sandra and Gina debrief their experience in creating this video.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 20)

2. Exploring Inconsistencies

The microskill of exploring inconsistencies is designed to draw attention to discrepancies or contradictions you notice within or across conversations with the client. Some examples of potential inconsistences include (a) discrepancies between what a client says and what a client does, (b) contrasts between how a client describes their feelings and what their body language suggests about their affective experiences, (c) discrepancies between client thoughts and feelings, and (d) unexplained changes in thoughts, feelings, or behaviour across time. Notice that in the previous sentence we used the qualifier potential inconsistencies to avoid counsellor judgement and simply invite share exploration.

The language of confrontation is sometimes used in other resources instead of exploring or describing inconsistencies. However, because of the values-based, relational practice lens of this resource, we attend to the inferences inherent in the language of confrontation that imply power-over, counsellor-centred perspectives. We chose instead to use the more invitational and collaborative language of exploring inconsistencies. No human being is completely congruence and consistent among domains of experience or across time, contexts, or relationships, and for many people such consistency would be unhealthy or unsafe. Recall our roots in postmodern and constructivist epistemologies that undergirded our argument that even what we view as self is fluid, contextualized, and responsive to relationship in-the-moment. Inconsistencies are also important starting places for growth and healing, opening the door for counsellors and clients to talk about, and potentially shine a light on, those thoughts, feelings, behaviours, stories, relationships, or experiences that are more life-enhancing and health-expanding.

It is often helpful to bring such discrepancies into awareness and to explore them as part of the process of constructing a shared understanding of client multidimensional lived experiences. However, it is important to do so in a way that remains tentative, collaborative, invitational, and responsive to the cues you receive from the client. It can be particularly helpful to make use of the client’s actual language (i.e., paraphrase) when describing the inconsistency, rather than adding layers of inference on the part of the counsellor. By foregrounding the client’s words, you offer an opportunity for them to clarify their intentions or to self-reflect on the inconsistencies before you begin to co-construct meaning with them.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement or question |

|

|

|

Exploring inconsistencies as a foundation for meaning-making

Animated video

In the animated video below we pick up on the story of Lionel and their missing tail. Look for places where the counsellor uses the microskills of reflecting meaning and exploring inconsistencies to co-construct meaning with Lionel.

© Sandra Collins (2021, May 12)

New counsellors are sometimes uncomfortable pointing out inconsistencies to clients. Notice this way in which the counsellor in this video seamlessly integrated doing that into the conversation in a way that was invitational as opposed to confrontational. Look for opportunities, as you go about your day-to-day life this week, to try out the skill of exploring inconsistencies. You may notice that it is a useful self-reflection tool as well.

Exploring inconsistencies

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In the video below, Gina watches for opportunities to use the microskill of exploring inconsistencies. It is a more rarely used microskill, in part because it requires clients to demonstrate some inconsistency in the first place. It takes time for Gina to find an opening to introduce this microskill. Pay attention to Gina’s use of both statements and questions for the purpose of exploring inconsistencies. It is the content of these counsellor verbalizations that places them into this category not the sentence structure.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 20)

When Gina points to the two parts of Sandra’s lived experience, it leads them into a deeper exploration about how Sandra makes meaning of this inconsistency. It also opens the door to finding a potential path forward for bringing Sandra’s experience with art into her other work. Note that when Gina combines two microskills together in the same statement (e.g., questioning and reflecting meaning), we only code the last statement.

Watch for opportunities in your applied practice activities to open the door to the counsellor’s use of this skill by deliberately sharing inconsistencies in your role as client.

3. Summarizing

One of the ways that counsellors can support the process of co-constructing meaning with clients is by effectively summarizing portions of the client–counsellor dialogue, at the beginning or end of the session and at various transition points throughout the conversation. The purpose of summarizing is to highlight and draw attention to themes, common threads, underlying thoughts and feelings, or conclusions that emerged from the conversation. Effective summarizing provides the client with an opportunity to reflect further on these highlights, offers new meaning or inference for client consideration, and helps make the overall flow of the conversation more meaningful.

Summarizing is very similar in linguistic structure to both reflecting meaning and reflecting feelings. All of these microskills should be succinct and capture the essence of the conversation. All three include inference(s) that the counsellor has made while listening to the client, except for the type of summarizing that is referred to as an agenda summary. The main difference between these three microskills is that reflecting meaning or feeling occurs immediately after the client shares something with the counsellor and refers to that most recent client verbalization; whereas, summarizing considers emergent theme(s) across a broader chunk of the conversation, and integrates ideas from a number of client–counsellor exchanges. Consider the dialogue below, in which the counsellor reflects meaning twice, adding inference each time, and then summarizes the conversation, pulling out a theme (inference) that runs through the entire interaction.

| Client: | I have been thinking a lot about that interaction with my mother. I realize that as soon as I walk into the house, I start to behave in the same way I did when I was 13 years old. Nothing ever changes. I open up a little bit to her. She responds with some sort of judgement. I clam up and pout for the rest of the visit. |

| Counsellor: | You struggle find your way back to your adult self. [Reflecting meaning] |

| Client: | Exactly! The adult me is long gone as soon as the interaction happens. Sometimes, I’m still stuck in that child place when I get home. My partner can tell immediately, and they have learned a few tricks to bring me back into the here-and-now. It is such a relief to feel like myself again. |

| Counsellor: | You aren’t yet able to use those tricks on your own, even though you welcome them from your partner. [Reflecting meaning] |

| Client: | Yeah. That’s interesting. I can hardly wait to get home to be with someone who treats me so completely differently. They can see in a moment what I need, and they always step up without judgement or demanding anything from me. |

| Counsellor: | What is also interesting is that in both your interactions with your Mom and with your partner, it is the other person who appears to have the most influence over your sense of self in the moment not you. [Summary] |

| Client: | Hmm. That is an interesting observation. I hadn’t thought about it that way. I do seem to be giving up my sense of control over my own reactions in both places. I need some time to process this a bit more. |

It is also important to distinguish between a thematic summary, which is most effective in supporting co-construction of understanding of client lived experiences, and an agenda summary. Here are a few other examples of possible thematic summaries, drawing on the client–counsellor interaction above:

One of the main themes is your need to feel affirmed by those most close to you.

You are really tired of feeling like you don’t have control your ability to stay rooted in your adult self.

These types of bottom-line summaries increase the meaningfulness of the dialogue for clients by offering them key elements for further reflection. These thematic summarizes can be contrasted with the more descriptive agenda summaries. It is much less meaningful to the client to provide a simple list of what you talked about: We started off focusing on your interaction with your mom and then contrasted that to your interaction with your partner. Notice that in an agenda summary nothing new is added that invites further reflection on the part of the client. In contrast, a well-worded thematic summary can prompt an aha moment for the client as a new level of meaning emerges from the dialogue.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

|

Like all the other microskills we have reviewed so far, the act of summarizing a conversation is not value-neutral in that the counsellor necessarily focuses attention on certain elements of the client’s experiences and excludes others. By pulling together emergent themes or meanings across a portion of the dialogue, you have an opportunity to intentionally highlight the client’s values, aspirations, strengths, or agency, where appropriate.

Summarizing

Animated video

In our final encounter with Lionel the counsellor uses the microskill of summarizing at several points in the conversation to pull out the emergent themes. Try to distinguish between the counsellor’s use of reflecting meaning versus summarizing, along with identifying the other microskills that are used.

© Sandra Collins (2021, May 12)

Summarizing

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this video Sandra demonstrates a variety of microskills to explore Gina’s presenting concern, focusing in on the meaning that Gina makes of the challenge she faces in managing her schedule. Notice how Sandra immediately uses questioning and reflecting meaning to focus attention on Gina’s thoughts, beliefs, and values with the intent of undergirding the change in behaviour Gina anticipates making.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 20)

Throughout the video Sandra demonstrates experience-near reflecting meaning to continue to draw out Gina’s values and beliefs. Towards the end of the video attend to how Sandra offers a summary to pull together meaning that arose from their conversation. Summaries serve to structure, and add meaningfulness to, the conversation.

A counselling session is similar to writing a graduate paper but written in reverse. Both must be structured to be meaningful to the reader (or listener) and must support meaningful connections between key themes. In a graduate paper, you begin with your thesis statement, develop your key arguments, then flesh out those arguments with subpoints. In a counselling session, following the client’s lead, you begin with the subpoints. Next, you summarize short segments of the session to pull out a broader theme (key arguments), and finally, towards the end of the session, you synthesize the dialogue into an overall summary (thesis), drawing out what you hope is most meaningful and relevant to the client.

4. Skills Synthesis

Chapter 6 skills synthesis

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this conversation with Gina, Sandra demonstrates the microskills introduced in this chapter. Pause to identify each skill to reinforce your learning. Note a couple of microskills from previous weeks that Sandra chooses to integrate to be responsive in-the-moment to what Gina was sharing with her.

You will notice that Sandra tends to use “I wonder” as a lead-in to certain microskills. This makes differentiating the skills a bit less clear in a couple of spots. We have coded the skills based on the overall structure and observable intention of the counsellor verbalization. Pay attention to your own verbal habits, attending to whether they add to, or distract from, the clarity of your conversations.

B. Techniques

We have positioned co-creating language as a technique rather than a specific microskill for two reasons (a) we are being purposeful in keeping the microskills as distinct from each other as possible to make it easier for you to distinguish one from another and (b) co-creating language is a broader process that most often includes a sequence of microskills.

1. Co-Creating Language

Part of the process of co-constructing meaning involves offering up language for client challenges (and in Chapter 8 for their preferred outcomes) to see what resonates with the clients and supports further evolution of meaning. Paré (2013) spoke of the constructive power of talk: “We construct and reconstruct our lived realities through talking and listening” (p. 37). He referred to this as a world-making activity , in which metaphors, both personal or cultural, can emerge and provide a focus for meaning-making. What is perhaps most important in co-creating language with clients is that clients are given the first and final words on the choice of words or phrases that best represent their lived experiences. Paré (2013) referred to client ownership over metaphors and other language choices as naming rights. This does not mean that the counsellor is not an active participant in the co-creating of meaning or that clients cannot select specific words or phrases offered up by the counsellor to integrate into their self-understandings. However, it does mean that they have the right to choose the words and metaphoric imagery that resonate best for them.

Consider the client–counsellor interaction below that reflects the technique of co-creating language. This conversation starts out in the same way it did earlier in the chapter (first two rows are identical), but the focus moves to the language of the client’s adult self versus their child self. Notice that the counsellor continues to work with this metaphor (compared to the earlier example), because it appears to resonate with the client and becomes the focus of their attention.

| Client: | I have been thinking a lot about that interaction with my mother. I realize that as soon as I walk into the house, I start to behave in the same way I did when I was 13 years old. Nothing ever changes. I open up a little bit to her. She responds with some sort of judgement. I clam up and pout for the rest of the visit. |

| Counsellor: | You struggle find your way back to your adult self. [Reflecting meaning] |

| Client: | Exactly! The adult me is long gone as soon as the interaction happens. Sometimes, I’m still stuck in that child place when I get home. I had not thought about this contrast between these two parts of myself, but now it seems so obvious to me. |

| Counsellor: | Tell me more about how you see these two selves, the adult self and the child self. [Probing] |

| Client: | The adult self is the one I take to work with me, who can juggle lots of tasks, move competently and confidently through their day, and not let other people’s opinions or demands throw them off (at least not for long). |

| Counsellor: | You look up to the adult self and have a sense of security when they are around. [Reflecting meaning] And what about the child self? What are they like? [Questioning] |

| Client: | They feel hurt and lonely most of the time. So they act out by pouting and withdrawing, hoping that this will bring them the attention they crave. |

| Counsellor: | You are drawn toward protecting the child self, because of their vulnerability. [Reflecting meaning] |

| Client: | Of course. I think that is why I get stuck and paralyzed, and at the same time I run away and try to disappear. |

Counsellors’ ability to pick up on and mirror client language use and to introduce new words into the conversation that demonstrate their understanding of client cultural experience and worldviews have been identified as helpful factors in developing an initial client–counsellor relationship (Willis-O’Connor, 2016) and in the development of a shared understanding client challenges and the contexts in which they occur (Paré, 2013; Paré & Sutherland, 2016). There is always an inherent risk in contributing a language to the conversation that the counsellor may miss a chance to hear from the client their preferred language for a particular experience. One way to avoid this issues is to continually foreground the relational practices introduced in this ebook in every interaction. How might holding an ethic of care, assuming an attitude of cultural humility, or engaging a not-knowing stance, for example, help you avoid over-running the client perspectives with your language preferences or assumptions?

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Question or statement |

|

|

|

Earlier in the chapter we introduced the idea of metaphoric language as a way to make meaning with clients. The process of co-creating language offers an opportunity to co-construct or foreground client metaphors, particularly cultural metaphors. Although the example below does not draw on Sandra’s actual cultural identities , it is grounded in the activities that bring value to her life and sense of self.

Co-creating language: Client-centred metaphors

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this video Gina picks up on an earlier conversation with Sandra about gardening (see the Reflecting Meaning section). Notice how Gina looks for opportunities to co-create language that has the potentially to provide additional meaning to Sandra’s experience. We have identified some of the microskills from previous chapters as well as those introduced in this chapter.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, May 12)

In this example, the metaphor was less linguistic in nature and more visual, although they did begin with piecing together meaningful language. One of the powerful things about metaphors is that they often introduce images that connect with verbal imagination or visualization. Other times, they may offer more visceral or embodied connections. In each case, the metaphor is strengthened by drawing on other senses, as Gina and Sandra did in this video.

Co-creating language

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

Recall that counselling techniques most often involve a combination of microskills. In the previous video we identified the portion of the video where Gina was engaged in co-creating language with Sandra, and we labelled the particular microskills she was using. In this video, we instead leave it with you to identify the specific microskills that supports the technique of co-creating language at certain places in the video.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 20)

Notice how Sandra pauses after offering the metaphor of baskets of eggs to see if this language fits for Gina. Consider how you might introduce new language in a way that is tentative and client-centred.

Gina and Sandra debrief this video below, offering insights into the potential challenges for counsellors in drawing on metaphorical language with clients. Consider how you might navigate these challenges?

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 20)

We will revisit the process of co-creating language in more depth in Chapter 8, when we introduce the technique of exploring cultural meanings with clients, and in Chapter 9 as a foundation for the techniques of reframing and externalizing.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

A. Reflecting Critically on Language

At the beginning of the chapter we talked about the sociocultural construction of language and the power of cultural metaphors to compose worlds. Throughout this ebook we have attempted to model critical reflection on language by challenging some of the common terminology in counselling and psychology that is embedded in eurowestern worldviews and by inviting consideration of client perspectives, values, and views of health and healing. The processes of co-creating language and meaning-making with clients require you to be willing and able to hold tentatively to the language and meaning that you associate with various cultural groups, with health and healing, with the kinds of challenges that clients bring to counselling, and so on. Holding tentatively to your own perspectives and engaging openly and creatively with clients will support meaning-making processes that are life-expanding as opposed to life-limiting.

Listening with an open mind and open heart

In this reflective practice activity we invite you to examine critically the influence of your own socioculturally embedded assumptions and biases as you explore the intersections of identity and meaning related to the term, two-spirit, which is a powerful cultural metaphor.

© them (2018, December 11)

The problem of naming, noted in the video, applies broadly to co-creating language and meaning-making across culturally diverse perspectives. Notice also the within-group differences among Indigenous nations pointed out in this video. Pay attention also to the ways in which language is critical to world-making (as well as being implicated in the world-crushing processes of colonization). What are the implications for client-centred, life-enhancing co-creation of language and foregrounding of cultural metaphors in conversations with clients?

B. Enlisting Your Own Story

Let’s extend the ideas of the sociocultural construction of language, knowledge, and meaning to your own story. Take a few moments to reflect on the ways that you are currently conceptualizing the challenge you face and the contexts in which it has arisen. Then step back to consider the assertion that we all hold multiple versions of ourselves and multiple narratives of our lives that are influenced by our cultural identities, life experiences, sociocultural locations, and so on.

Metaphors as a foundation for reflective practice

by Anita Girvan

In this last video Anita invites you to draw on the concept of metaphors as you reflect on how your own story has evolved up to this point in the ebook.

© Anita Girvan (2021, May 24)

Try to look at your story from a different perspective, apply a new lens, test out different language, create a linguistic or visual metaphor (or several alternative metaphors), or otherwise step outside of your current assumptions to consider new possibilities for understanding your story. If you notice conflicting or alternative metaphors emerging, what meaning do you make of this tension or evolution? Which metaphor might you choose to carry forward as life-enhancing or life-affirming?

It is possible that your journey through this ebook has initiated a new narrative for you, shifting the lens through which you view yourself and others. Attend to the concepts, principles, and practices in this chapter that may support you in deepening your understanding of, or building upon, that new narrative. How might you make use of the metaphors you identified to strengthen that new story line?

C. Engaging with Client Stories

Macey’s story: Part 6

As you watch Part 6 of Macey’s story, consider the implications of her sociocultural context on the language she uses and the ways in which she makes meaning of her lived experiences.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, March 18)

Prompts for reflection:

- What words did you pick up on that may form a foundation for further meaning-making with Macey?

- What language might you add to the conversation as you begin to explore what Macey has identified as the gendered context of her challenges?

- How might you support Macey to re-construct and re-language her own version of what is means to be female?

- Consider her introduction of the word yun at the end of the video. How might you explore more fully with Macey the meaning she attaches to this term?

- How might you draw on the socioculturally embedded language and meanings introduced by Macey to support her desire to move from life-constricting to life-expanding versions of herself and the contexts of her life?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

You may want to print out the applied practice activities before you begin your practice session.

A. Responsive Microskills

Preparation

You may choose to bring forward the story you have been working on as part of the Reflective Practice in each chapter, or you may identify another challenge you are currently facing for each of the applied practice activities (below). In either case take some time to reflect on the ways in which your story is shaped by your sociocultural contexts. Attend in particular to the ways in which meaning is constructed within families, cultures, communities, and society as a whole. Reflect in advance on the ways in which you attach meaning to your story based on these contexts. By exploring multiple dimensions of a single story for all of the applied practice activities in this chapter, you will begin to mirror more closely the counselling process with clients. Revisit the guidelines related to the use of personal stories and challenges in skills practice:

- Select real, but not traumatic, challenges to explore.

- Choose a topic that is not easily solvable; one that offers you a sufficient challenge to talk about for each of the skills practice activities.

- Don’t share stories you are not comfortable having your partner record for their learning purposes.

- If the conversation unexpectedly goes in a direction you are not comfortable with, you can stop it anytime.

1. Warm-Up Activity: Experience-Near Responding

(30 minutes)

The purpose of this activity is to experiment with reflecting meaning as a foundation for the co-construction of shared understanding of client challenges.

Preparation

Revisit the importance of experience-near versus experience-distant responses. Provide each other with a brief summary of your challenge, so that you have a starting place for these conversations and can move more quickly into exploring thoughts and beliefs.

Skills practice (3–4 minutes each)

- Client: Talk about your challenge, focusing on sharing your thoughts (rather than emotions). Offering up content in the cognitive domain will support your partner’s skills practice.

- Counsellor: Draw on whatever microskills are useful in the first few minutes to engage the client in dialogue about their thoughts about the challenge they are facing. Then introduce reflecting meaning. Take wild guesses at the underlying meaning in what the client is saying (i.e., experience-distant reflecting).

- Client: Respond as you would normally to someone who has not understood what you have said.

Skills practice (3–4 minutes each)

- Counsellor: Continue to use the microskill of reflecting meaning, attending now to carefully co-constructing shared understanding by using experience-near responses.

- Client: Respond in whatever way seems natural in the moment.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback to each other on (a) your ability to stay focused in the cognitive domain and (b) the quality of experience-near reflections in the second part of the activity.

- What was it like, in the roles of both counsellor and client, to stay focused on thoughts and beliefs? How did this differ from your experience of focusing on emotions and embodiment in Chapter 5? What are the implications for working with clients who might incline toward one domain or the other?

2. The Sociocultural Construction of Meaning

(40 minutes)

Preparation

It is important to keep revisiting the overall framework for conceptualizing client lived experiences so that you keep in mind where you are at in this process. At this point you continue to work towards answering the second question (below): How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise?

Figure 4

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

Skills practice (9–10 minutes each)

The purpose of this activity is to continue to explore the meaning you attach to the challenge you have each identified, with a particular focus on the sociocultural contexts that influence meaning-making.

- Client: Talk about your challenge, continuing to focus on your thoughts.

- Counsellor:

- Choose one or more of the microskills from earlier chapters to invite the client to consider the sociocultural contexts that may influence how they think about the challenge they are facing. Here are a few examples:

- Providing transparency: Human beings learn through interacting with other people and the world around them. These broader contexts of our lives often affect how we think about health, how we understand the challenges we face, what we value, and so on.

- Questioning: What messages did you receive from your family (or your cultural community) that might affect how you view your current challenge?

- Probing: Identify some of the significant people, communities, or other contexts of your life that might influence how you are thinking about this challenge you face.

- Choose one or more of the microskills from earlier chapters to invite the client to consider the sociocultural contexts that may influence how they think about the challenge they are facing. Here are a few examples:

- Client: Introduce one of the sociocultural influences that you considered in your preparation for these applied practice activities.

- Counsellor:

- Use the microskill of reflecting meaning to offer inferences (i.e., new language, underlying meaning) about the client’s thoughts, paying particular attention to any clues to their contextualized assumptions, beliefs, and values.

- Draw on the microskill of checking perceptions to ensure that your reflections are experience-near, and adjust them as appropriate.

- Client: Continue to respond as naturally and honestly as possible.

- Counsellor:

- After each 3–4 minutes of dialogue, pull together what you have learned about the client’s values, beliefs, and assumptions using the microskill of thematic summarizing.

- Consider checking perceptions after each summary.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback to each other on (a) your ability to stay focused in the cognitive domain and (b) the degree to which the reflections and summaries were experienced as experience-near by the client.

- Brainstorm additional ways to invite consideration by the client of the sociocultural influences on meaning-making.

As you deepen your understanding of the challenge the client is facing, you may be tempted to try to solve it by offering suggestions, brainstorming solutions, or giving advice. For some of you this will be one of the biggest challenges you face as you enhance your ability to engage in care-filled, culturally responsive, and client-centred relationships. Please resist the urge to resolve the challenge; just listen and learn from the client. Premature foreclosure on fully exploring client challenges can mean you do not actually appreciate the underlying thoughts, beliefs, values, or assumptions that may be most helpful for the client to explore. We intentionally do not begin to talk about preparing for change until Chapter 10. Your main foci until then are (a) to listen, listen, listen and (b) to come as close as you can to a shared and detailed understanding of the client’s lived experiences, their challenge, and the contexts and multiple dimensions of the challenge.

3. The Sociocultural Construction of Meaning, Continued

(40 minutes)

Preparation

In your role as client, identify one or two examples of ways your perspectives on your challenge diverge from the sociocultural contexts of your lives (e.g., differences between your perspectives and those of others in your lives, between your underlying values and the choices that you make in certain contexts, between two different beliefs or assumptions you hold). The intent is for you to introduce an inconsistency to which the counsellor can respond. You might, for example, experience gendered messages that don’t fit for you (recall Macey’s story) or you might experience life-limiting messages in which you are stuck. Alternatively, you might pick up on something from the previous two activities and present a different picture to the counsellor now.

Skills practice (9–10 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Start off by summarizing (thematic) what you learned about the client’s socioculturally embedded experiences in the previous activity, keeping the focus on thoughts and beliefs.

- Continue to draw on the microskill of reflecting meaning to explore the client’s thoughts about the challenge they face, paying particular attention to any clues to their contextualized assumptions, beliefs, and values. Integrate microskills from previous chapters as appropriate.

- Client: Find an opportunity to offer clues to a conflict or discrepancy in your thinking or between your thinking and other aspects of your lived experiences.

- Counsellor:

- Try out the microskill of exploring inconsistencies to draw attention, gently and respectfully, to the perceived conflict or discrepancy.

- Continue to draw on the microskill of reflecting meaning to co-create an understanding of the significance of this inconsistency to the way the client is thinking about their challenge.

- Client: Continue to respond as naturally and honestly as possible. If the counsellor struggles to highlight the inconsistency, provide more information to support them.

- Counsellor:

- Repeat your use of exploring inconsistencies, as appropriate, and continue to reflect meaning as a foundation for shared meaning-making.

- End this segment by summarizing what you have learned so far about the client’s challenge, attending to thoughts, beliefs, values, and assumptions.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide specific, descriptive, nonevaluative feedback to each other related to your attempts at summarizing. If you struggled to be clear and concise (Chapter 5), practice refining one of your summaries together.

- How comfortable were you in drawing attention to a discrepancy or inconsistency in the client’s story? How might you increase your comfort level with this microskill?

- From the client perspective, what was most helpful about the invitation to attend to the conflict or discrepancy you face? To what degree did the counsellor demonstrate an ethic of care (Chapter 2) and maintain a focus on client strengths (Chapter 4) while pointing out this inconsistency? How might these lenses support effective and responsive use of this microskill?

B. Responsive Techniques

1. Engaging Metaphors

(40 minutes)

Preparation

In your role as client, think ahead to a metaphor, personal or cultural, that might be useful to your own understanding of your challenge or to developing shared understanding with the counsellor. You may or may not introduce this. Ideally, such metaphors emerge naturally and are co-constructed within the client–counsellor conversation. However, these skills practice activities are time-limited and somewhat contrived. So having an image or metaphor as a starting place may support your partner’s practice of the technique of co-creating language.

Skills practice (9–10 minutes each)

Counsellors and clients co-construct language by generating and refining words or phrases that support shared meaning-making. These may not be metaphors; some of the language that is generated may be more literal. For example, you might infer, You are facing a dilemma (literal), in contrast to suggesting, You can’t decide which door to open (metaphoric). Both evidence the technique of co-creating language. In this activity, take the opportunity to play with less literal, more metaphoric language.

- Client:

- Continue to talk about the challenge you are facing, heading in a direction that might open the door to exploring the metaphor you have been considering.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on reflecting meaning and, where appropriate, perception checking to pick up on portions of the conversation that seem most meaningful to the client. Integrate other microskills as appropriate.

- Look for opportunities to introduce metaphoric language for the client’s consideration through continued use of reflecting meaning.

- Client: Find an opportunity to offer clues to the metaphor you have been thinking about if an alternative does not emerge naturally from the conversation.

- Counsellor:

- Continue to draw on the microskill of reflecting meaning to work with the client to refine the emergent metaphor in a way that is most meaningful and helpful to them.

Reflective practice and feedback

- What did the co-creation of a metaphor contribute to your shared understanding of the challenge the client is facing?

- Revisit the information on experience-near responses. To what degree did the metaphor you generated come close to the client’s intended meaning? Brainstorm freely other metaphors that may be equally or more useful to each of you in getting a clearer sense of the challenges you are facing.

2. Conceptualizing client lived experiences

(30 minutes)

Skills practice (9–10 minutes each)

Continue to lean into building shared understanding of the challenge the client is facing, focusing predominantly on thoughts and beliefs.

- Counsellor:

- Use a combination of any two of these microskills and techniques, reflecting meaning, exploring inconsistencies, checking perceptions, or co-constructing language.

- Use this final skills practice to pull together what you have learned about the client’s challenge throughout these activities, keeping the focus on thoughts and beliefs.

- Client: Respond as honestly and openly as possible.

- Counsellor: Periodically use summarizing to focus attention the most relevant themes, language choices, metaphors, and so on.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Reflect together on some of the guidelines for responsive verbal and nonverbal communication provided so far in the ebook: ethic of care and responsive nonverbal communication (Chapter 2), open and invitational microskills (Chapter 3), strengths-focused lens (Chapter 4), clear and concise microskills (Chapter 5), and experience-near responding (Chapter 6).

- How helpful are these principles in supporting your client-centred, care-filled, and responsive use of counselling microskills and techniques? What evidence of them emerged in this final skills practice activity? What additional tips might you add to support your continue development of proficiency with the skills and techniques introduced and the overall goal of facilitating responsive relationships?

REFERENCES

Bava, S., Gutiérrez, R. C., & Molina, M. L. (2018). Collaborative-dialogic practice: A socially just orientation. In C. Audet and D. Paré (Eds.), Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice (pp. 124–139). Routledge.

Collins, S. (2018a). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices: Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 441–505). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018b). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Combs, G., & Freedman, J. (2018). The therapist as second author: Honoring choices from beyond the pale. In C. Audet and D. Paré (Eds.), Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice (pp. 85–97). Routledge.

Cook, K. (2018). Extraordinary challenges to live ordinary lives: Young adults with life-limiting conditions. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 530–554). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Gergen, K. J. (2015). An invitation to social construction (3rd ed.). Sage.

Killick, S., Curry, V., & Myles, P. (2016). The mighty metaphor: A collection of therapists’ favourite metaphors and analogies. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 9, E37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X16000210

Ko, G. (2014). Inspiring bilingualism: Chinese-Canadian mothers’ stories [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Athabasca University.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Interpretation. Merriam-Webster dictionary. Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Metaphor. Merriam-Webster dictionary. Retrieved April 11 2021, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Paré, D., & Sutherland, O. (2016). Re-thinking best practice: Centring the client in determining what works in therapy. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of Counselling and Psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 181–202). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Socholotiuk, K. D., Domene, J. F., & Trenholm, A. L. (2016). Understanding counselling and psychotherapy research: A primer for practitioners. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 247–263). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Wagener, A. E. (2017). Metaphor in professional counselling. The Professional Counselor, 7(2), 114–154). https://doi.org/10.15241/aew.7.2.144

White, M. (2005). Workshop notes. https://dulwichcentre.com.au/michael-white-workshop-notes.pdf

Willis-O’Connor, S., Landine, J., & Domene, J. F. (2016). International students’ perspectives of helpful and hindering factors in the initial stages of a therapeutic relationship. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 50(3, Supplement), S156–S174. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/