Chapter 11 Enhancing Relational Resiliency

by Gina Ko, Sandra Collins, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Amy Rubin, Jason Brown, Lisa Gunderson, Melissa Jay, and Don Zeman

In this final chapter we invite you to consider how to continue to prepare yourself for the important role of bearing witness to client stories, stories of joy and hope as well as stories of distress and trauma. We introduce strategies for mitigating compassion fatigue through attending proactively to your own health and healing, include integrating self-care practices. We then take a look at what happens for counsellors and clients when relationships go awry, and we explore ways to avoid, and to respond to effectively, relationship ruptures.

In this final chapter we invite you to consider how to continue to prepare yourself for the important role of bearing witness to client stories, stories of joy and hope as well as stories of distress and trauma. We introduce strategies for mitigating compassion fatigue through attending proactively to your own health and healing, include integrating self-care practices. We then take a look at what happens for counsellors and clients when relationships go awry, and we explore ways to avoid, and to respond to effectively, relationship ruptures.

Figure 1

Chapter 11 Overview

RESPONSIVE RELATIONSHIPS

A. Self-Care

I have learned the importance of self-care by being a mother in graduate school, completing my masters and doctoral degrees, and also by becoming a registered psychologist. To me self-care is about self-compassion and self-love. I know that I have the ability to hyper focus, to stay on task, and to do creative work early mornings. I wake up at 5:00 am every day (except some weekends) so that I can be productive in the mornings and focus on work while my children are still sleeping.

After about 2 hours, I take a break to make coffee and listen to the daily news. Throughout the day, I pause between activities. Some of these pauses are longer (e.g., for meals, playing the violin, video games). I love to read. I have books around the house, and I pick up a book to read few pages. Currently I am reading five books (psychology, counselling, nonfiction, fiction, memoir). I find that I need to be constantly stimulated and engaged by switching tasks often, but not too often; I have learned there is a cost to the latter. My superpower is taking short naps (between 5 and 30 minutes) for optimal brain boost.

In the evenings I have dinner with my family, and we play ping pong, volleyball, work out in the basement, and then watch a Chinese series together. Some evenings I see clients, and that may mean some of these activities are not possible. However, I know that time with my children and spouse feed my heart, and I connect with them throughout the day.

I no longer feel guilty about engaging in self-care. However, during my first few years of graduate school I thought that everything I read had to be about counselling psychology; otherwise, I was not being productive. I did not allow myself to watch television or play games. This shifted several years ago when I went to Australia with my peers and two professors to engage in an international doctoral seminar with Australian and Chinese colleagues. My professors and peers talked about movies and shows they were watching, and I realized I had been cheating myself out of such entertainment, because I thought it would take away from my studies. I learned that breaks are a must to continue to engage academically. Since then my streaming accounts are worth the monthly fee.

I am getting better at noticing when I need to take a break, deciding what to do during those breaks, and giving myself permission to take care of myself in order to care for my family and my clients.

Gina

1. Compassion Fatigue

Countering compassion fatigue with self-care: Part I

Contributed by Karen Cook

Engaging in our multiple roles as counsellors from a relational position of compassion and care can be emotionally, psychologically, and physically taxing. What happens when counsellors, community members, and other care companions are stretched past the limits of their own compassion? For this learning activity, I invite you to create a wordle or word cloud (see the free programs listed at https://monkeylearn.com/blog/wordle/, or choose a different tool if you like).

Your word cloud should contain words that you associate with the term compassion fatigue. Create this before you read further about how compassion fatigue is defined in the counselling literature. Consider your own experiences as someone who both gives and receives compassion and empathy. Choose colour and design that speaks to you of your emotional reaction to this term.

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2022. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#countering. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Throughout this ebook we have encouraged you to lean actively into client stories and to create space for them to express both what is going on for them internally and their lived experiences in the various contexts of their lives. We have also invited you to bring yourself as a whole being into engagement with your clients in ways that are open, authentic, and characterized by mutual empathy. These are all important relational practices for counsellors who want to build growth-fostering relationships with clients to optimize client potential for health and healing. However, this positioning comes with risks if you do not attend, proactively, actively, and consistently, to your own health and well-being.

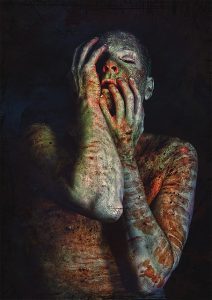

We all suffer

Take a moment to sit quietly with the image on the left. Paré (2013) argued that compassion is a way of being that involves a willingness to open to another person’s suffering as part of our shared humanity. Reflect on the notion of suffering as a core human experience and a foundation for connection and trust-building between counsellor and client. From a social justice perspective, how might your position of relative privilege or marginalization impact your ability to connect or empathize with clients’ suffering? How willing and able are you to be present to another person’s pain? How might you enhance your capacity for a compassionate stance towards all clients?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2022. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#suffering. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

One of the risks that counsellors face over time, as they move into compassionate engagement with clients and their stories, is the development of compassion fatigue. Compassion fatigue is an umbrella term for the secondary or vicarious stress or trauma that can result from opening oneself to, and empathizing with, the painful and distressing experiences of clients (Buchanan & Keats, 2015; Keats, 2016). The main characteristic of compassion fatigue is a decrease in, or loss of, the ability to feel compassion and empathy towards others (Sinclair et al., 2017). Counsellors may also experience significant emotional and cognitive disturbance or dysregulation (Hargons et al., 2017). Keats (2016) strongly recommended that counsellor education programs explicitly incorporate a focus on self-care as a way of preparing new counsellors to recognize and prevent compassion fatigue.

Countering compassion fatigue with self-care: Part II

Contributed by Karen Cook

Now that you have some sense of the meaning and impact of compassion fatigue, on both counsellors and clients, I invite you to create a second wordle or word cloud (see the free programs listed at https://monkeylearn.com/blog/wordle/, or choose a different tool if you like). The second word cloud should depict self-care and other strategies to prevent or counteract compassion fatigue. You may want to search the Internet for some ideas.

Now compare your two wordles, attending to both your cognitive and emotional reactions. Choose one strategy from your second wordle that you can begin to implement this week.

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2022. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#countering. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

2. Self-Compassion

We have integrated messages about self-care throughout this resource. It is very important that counsellors are able to recognize their personal vulnerabilities (emotional, cognitive, physical, and interpersonal) and that they put in place plans to support their own health and healing (Collins, 2018a). This may be particularly true for counsellors from marginalized populations or who work with members of nondominant groups, because constant encounters with, and oppression from, dominant discourses and norms within society and within the professions of counselling and psychology create additional layers of stress (Huezo, 2018). We invite you to reflect on, and to be compassionate toward, your own woundedness by working through the following learning activity.

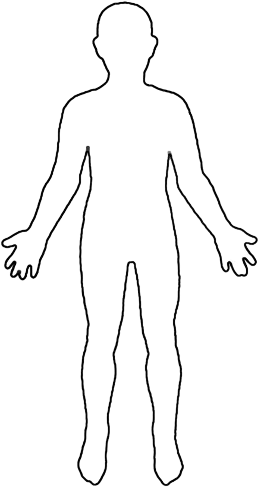

Wounded healers: A body map approach

Contributed by Jason Brown

Therapy is difficult. It takes a toll intellectually, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. One way of understanding this energy expenditure is the concept of the wounded healer.

The wounded healer has origins in Greek mythology (Kirmayer, 2003). Askepios, the son of the god Apollo and the mortal Koronis, was wounded before birth by an arrow. At birth he was given to Chirton, a centaur. Chirton himself suffered from an accidental and incurable wound. Living a life of chronic pain and suffering he was unable to heal himself, but he could heal and teach others (Conti-O’Hare, 1998). Chirton taught Askepios the “art of healing” with “the capacity to be at home in the darkness of suffering and there to find seeds of light and recovery.” (Stone, 2008, p. 48).

Carl Jung (1951) first wrote about the wounded healer archetype in a psychotherapy context. Over his career Jung’s thinking moved away from the need for therapists to be objective and distant so as to have “clean hands” (p. 18). Jung later wrote about the need for openness and vulnerability with his observation that “only the wounded physician heals” (1963, p. 155).

By knowing our own wounds and healing, we acknowledge our own challenges and growth. In doing so we recognize the capacity for growth in others. We can then activate, enhance, and fortify those forces in our clients (Brown, 2019).

As therapists, we are expected to have our s**t together. That does not mean we must be perfect. Far from it. However, as students in supervised practice, we feel the pressure to meet expectations. And for good reason: We are being evaluated. This makes it a real challenge to show vulnerability during training. Sometimes we take that mindset into our practice.

But we have all been wounded.

We wear our mental, emotional, and spiritual wounds in our bodies (Hauke & Kritikos, 2018). Art therapy, “with its process of mark making and modeling, and in its creation of visible, material images and objects, offers a powerful medium for reconnecting with physical objects and consequently with our own bodies” (Lewin, 2012, p. 146).

Wounds are injuries. Some are large, and some are small. Some are serious, others benign. Some we receive early in life, others later. Sometimes we are immediately aware of the injury; sometimes it takes time or a particular experience for it to come to our attention (Brown, 2019).

As a dad to three teenagers (now), I have had many humbling as well as learning opportunities. My emotional woundedness from being socially excluded as a young person is awakened when my kids tell me about their own challenges with friendships. The hurt is like a sharp poke in the chest, and if I don’t pay attention to it, a heavy sadness will spread and weigh me down. My healing energy starts flowing when I pull away from the poke, dispose of it through writing and shredding, and later, celebrate the scar that the healed wound will leave behind. The scars are, for me, reminders that healing requires change.

Healing can come from medicine (traditional or western), counselling and psychotherapy, rehabilitation, accommodation, self-care, and support from others.

We have all experienced healing.

Reflect on your own healing

On the image to the left, note where and how you have experienced healing.

Use colours, shades, textures, symbols, locations, and sizes to represent your experiences.

Present your body map in a small group or invite a classmate, family member, or colleague to complete this activity with you.

- Discuss similarities and differences.

- Notice patterns in your own and others’ healing.

- Consider ways your own and others’ healing processes are activated. For example, where in your body do you find strength? How does it manifest? How can you use it to be helpful to a client?

Individually, come back to the body map, and note where you still have healing to do as well as when and how you expect to continue your healing journey.

Engaging self-compassion

Kristin Neff is well-known for their work on self-compassion (https://self-compassion.org/; https://centerformsc.org/). The following videos by Dr. Neff are designed to support you in developing or refining your sense of self-compassion. In this first video Dr. Neff describes what is meant by self-compassion by drawing a link between compassion for others and self-compassion.

© Kristin Neff (2011, January 18)

As you reflect on this video, consider without judgement the sources of your own suffering. Attend carefully to the self-talk that emerges as you identify these sources, and reflect on what makes these sources of suffering particularly meaningful to you. Then consider the influence of self-kindness on self-compassion.

© Kristin Neff (2011, January 19)

As you watch this final video, consider how the practice that Dr. Neff introduced might support you to prepare for, and sustain yourself, in your care-giving roles with your clients. You may find it useful to think of a time when you have struggled to maintain self-compassion as you engage with another person from a position of caring.

© Kristin Neff (2020, April 6)

In their more recent work, Dr. Neff identifies two forms of self-compassion: (a) tender self-compassion involves the ability to lean into your own experience, to stay with your pain, and to provide yourself with comfort and reassurance in-the-moment; and (b) fierce self-compassion is an active response designed to remediate your pain and suffering by standing up to oppression, setting clear boundaries, or acting on your environment to protect yourself (Neff, n.d.). Consider times in your life when you have experienced the need for either tender or fierce self-compassion. You may want to check out Dr. Neff’s Fierce Self-Compassion Infographic.

- Which of these approaches to self-compassion is most familiar to you?

- In what ways might you enhance the other form of self-compassion to create a more balanced approach?

3. Self-Care in Session

Self-compassion is inseparable from broader practices for self-care. These intentional practices of self-care are crucial means for helping professionals to prevent burnout or compassion fatigue and to cultivate resilience (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2011). As noted above mindfulness practices can enhance self-care and self-compassion (Coleman et al., 2016). It is important to focus on the gifts of helping along with purposeful caring for self so that you can be optimally available for clients (Skovholt & Trotter-Mathison, 2011). Self-care is an important ingredient in being able to be present and to stay grounded when counselling relationships are strained for one reason or another; without presence and grounding the counsellor cannot respond in a way that supports client well-being. Self-care is important both outside of, and within, interactions with clients.

Contributed by Melissa Jay

In the video below Melissa Jay revisits the thread of self-care by focusing on how she continues to ground herself, particularly when she experiences intense emotions, a rupture in the therapeutic relationship, or other difficult conversations with clients. She draws on principles of trauma-informed practice to support herself to stay connected to mind, body, spirit, and heart.

© Melissa Jay (2021, February 18)

Take a few moments to practice the principles Melissa introduced in this video. Repeat this practice several times over the next few days to reinforce your learning and to make it easily accessible in times when you or a client experience distress.

- Stay grounded: Attend to all five senses.

- Slow the process.

- Check in with feelings and embodiment.

- Shift from doing (talking) to being.

4. Zoom Fatigue

We invited Don Zeman, who has lots of experience in working in virtual environments, to explore the impact of spending so much time in synchronous conversations with others through videoconferencing. For many of us our virtual worlds have become a significant part of our daily interactions, and this was amplified during the pandemic. The term, zoom fatigue, has become part of common conversation in educational, counselling practice, and personal spaces. Attending to this phenomena is an important element of personal and professional self-care.

Zoom (videoconferencing) fatigue: What is it and how can we prevent or manage it?

Contributed by Don Zeman

About 10 years ago, Zoom was still in the formative and planning stages, with about 10 million participants by April, 2014, which expanded to 300 million by April, 2020 (Iqbal, 2020). What are some of the things that Zoom and videoconference users are experiencing and what are some of the phenomenon that may be involved?

Even though universities and other schools were already using platforms such as Zoom, COVID-19 largely influenced the shift to their use in multiple areas of life, and the total number of hours of work also increased (DeFelippis et al., 2020) along with the total number of hours of online connection. These are areas that are new or newer for most people, and even for those who may believe that they are used to Zoom, the novelty and skill acquisition increases mental exertion. Managing our own image on screen is mentally tiring (Morris, 2020), and seeing other faces enlarged on screen may be perceived as threatening (Wolf, 2020). Interpreting what we see and hear may be difficult, and concentration levels and brain work are set on high for long periods of time leading to brain and body fatigue (Lee, 2020).

Although Zoom has decreased technological delays between participant speech to very low levels, synchrony challenges of milliseconds make our brains work harder to overcome the delays (Johnson, 2020; Roberts & Francis, 2013) and the experiences of overlapping speech (Hilton, 2020). The delays and technological challenges that often occur within sessions may lead to, or increase feelings of, anxiety (Schoenenberg et al., 2014).

How can we avoid or manage zoom fatigue (Wiederhold, 2020)? Here is a collection of many possible useful suggestions that you may have used already, and which have been used by many others.

- Block time off before and after Zoom or videoconferencing sessions (Jackson-Wright, 2020).

- Start sessions with a group check-in on how everyone is doing (Petriglieri, 2020), and then consider doing a grounding or centring activity. Remind everyone to consider using mindfulness, breathing, or regulating exercises and activities during sessions (Ray, 2020).

- Take nonscreen comfort or bio breaks within sessions and between sessions (Segar, 2020).

- Turn off video and mute when not speaking (Fosslein & Duffy, 2020), and consider making use of the camera optional (Petriglieri, 2020).

- Move the camera, or yourself, off to the side so that you are not in the centre of the screen (Petriglieri, 2020), and use headphones and headsets (Chokkattu, 2020).

- If possible, use the built-in 40-minute time limit that Zoom has when using it for free, or consider limiting meetings, whenever possible to 40 minutes (Ryan, 2020).

- Use the many features that Zoom has such as backgrounds, annotation tools, and screen sharing, and become as familiar as possible with all of the features to decrease or even eliminate technological challenges during meetings (Ryan, 2020).

- Have one set space for where you do Zoom or videoconferencing meetings (Brown, 2020).

- If your camera is on, look around your space as this is something that humans usually do during in-person conversations (Brown, 2020).

Zoom meetings and other forms of videoconferencing are certainly here to stay and are likely to feature largely in our lives, especially for online learning programs. Understanding some of the consequences of our experiences and what happens to us in these meetings, as well as how we can manage or mitigate those influences, will help us be able to continue to participate in the meetings, lectures, and sessions that have become an increasingly large part of our lives.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

One of the reasons that is it so important to attend to your own health and healing though self-compassion and self-care practices is that you will inevitably encounter exchanges with clients that are difficult and sometimes heart-breaking. The healthier and more self-aware you are, the more prepared you will be to stay present and open in-the-moment as well as to be kind to, and gentle with, yourself retrospectively when things do inevitably go off the rails in your conversations with clients.

A. Resolving Relationship Ruptures

We, as counsellors, have all experienced relationship ruptures with clients, whether we are aware of them or not. Some are more dramatic than others. Simon Nuttgens kindly shared a couple of his difficult learning moments earlier in the ebook.

I recall a conversation with a client where my attempts at cultural inquiry did not go well at all. We’ll call him Sam. Sam was struggling with addictions. I was contacted by his sister who arranged the appointment. Sam would not come to my office, so I agreed to meet them at a neutral location, and his sister then left us alone to talk. The conversation was challenging, because Sam did not want to be talking with me. My thinking in-the-moment was: “If Sam doesn’t believe they have a problem with addictions, then this is not the place to start, so why don’t I try to get a better sense of who they are and what is important to them.”

However, by taking the presenting concern off the table, I was soon reminded that I had not built a sufficient relational foundation for our conversation, and more importantly, I had not even established an agreement with Sam for us to work together. This was his sister’s idea after all! He had every right not to be there and not to respond to my questions. But I didn’t really process any of this in-the-moment. Instead, I proceeded to invite him to talk about his current life to get a bit of context for what his sister saw as the problem.

I was at a point in my own professional development where I was learning more (mostly teaching myself more) about the influences of cultural identities and social locations on client challenges. So, I decided I would take this opportunity to engage in cultural inquiry to get a bit of a sense of Sam’s family and community contexts. Retrospectively, I can see that this choice had more to do with my learning agenda than with what Sam needed. I can’t remember what question I asked to start off this conversation. But I can clearly remember Sam’s reaction. They immediately stood up and started swearing at me, accusing me of seeing a Black guy and assuming they are all drug dealers and losers, just like every person in authority they had ever encountered.

I knew immediately that there was no coming back from this rupture, not because these types of difficult conversations are impossible to work through with our clients, but because Sam was not yet a client, and I had not invested the time required to build a relationship with them. There was no foundation of trust, no possibility that Sam had felt heard and understood and cared for without judgement. I had allowed myself to be swayed by the urgency in his sister’s concern for him, by my own good, but very poorly timed, intention to attend to culture and social location. But most importantly, I had not responded relationally the person sitting with me.

Fortunately, I did have the self-awareness to not focus on my own guilt and regret about the situation and to calmly accept his legitimate anger, to apologize, and not attempt to justify my queries. In my head, I started down the path of trying to explain that this was not what I meant, and I saw that this line of defence was about me, not about Sam. In retrospect, I can see how my lack of deep appreciation of the legitimate stigma he associated with counselling, and with people in authority generally, made my lines of inquiry inappropriate and insensitive.

Similarly to Simon’s rupture experience, I never saw Sam again. But I carry that encounter forward to support my own learning and professional development. I hope it is helpful to you.

Sandra

In the meta-analyses on evidence-based relationships and responsiveness summarized in Chapter 1, Norcross and Wampold (2018) identified managing countertransference and repairing relationship ruptures as probably effective in strengthening counselling outcomes. Similarly Parrow et al. (2019) identified relationship ruptures and repairs as one of eight evidence-based relationship factors that emerged in their research. From Sandra’s story above and those that Simon shared earlier, it is clear that relationship ruptures can occur in the very first encounters with clients, which will likely affect their willingness to seek help or to continue the counselling process in the first place. However, there are also many times when ruptures will occur in well-established counselling relationships, and it is important to prepare in advance to navigate them effectively. In this next section we look at the interplay of transference–countertransference on counselling relationships and then explore how values differences, often embedded in cultural worldviews, can contribute to relationship ruptures.

1. Transference–Countertransference

The interplay of transference–countertransference can arise in many difference contexts in counselling; however, it can be particularly complex and potentially damaging to clients when it is interconnected with cultural identities and social locations. This is one of the reasons that we have foregrounded concepts, principles, and practices in this ebook that can enhance your competencies in both relational responsivity and cultural responsivity. Jordan (2010) defined cultural transference as “bringing expectations of the past to bear on the present in a way that distorts current reality” (p. 26). Reflecting on Sandra’s story above, Sam’s legitimate response to being asked about cultural context in the absence of an established therapeutic relationship was amplified by Sam’s belief that Sandra was making the same assumptions about him that other people in authority (specifically, white people in authority) had made in the past. Although Sandra made several mistakes leading up to this conversational exchange, she was able to attend to, and intercept, her countertransference reaction. For Sandra, this countertransference reaction could have led her down one of these paths:

- Defensiveness: “That is not what I said. What I meant was . . .”

- Rationalization: “It is important for me to understand the various factors that might play into your struggle with addictions.”

- Blaming: “It looks like you have some challenges with people in authority that it might be important to address.“

It is not uncommon for counsellors to miss cues that transference or countertransference are happening in-the-moment, with insight arising only in retrospect.

- What are the implications of knowing that transference can occur without your awareness?

- What can you learn from the relational practices in this ebook that will enable you to create space for the expression of transference whenever it arises?

- What relational cues might you watch for to recognize transference on the part of the client?

- What proactive steps might you take to minimize your risk of inadvertently engaging in countertransference?

- How might you prepare yourself for challenging encounters with clients?

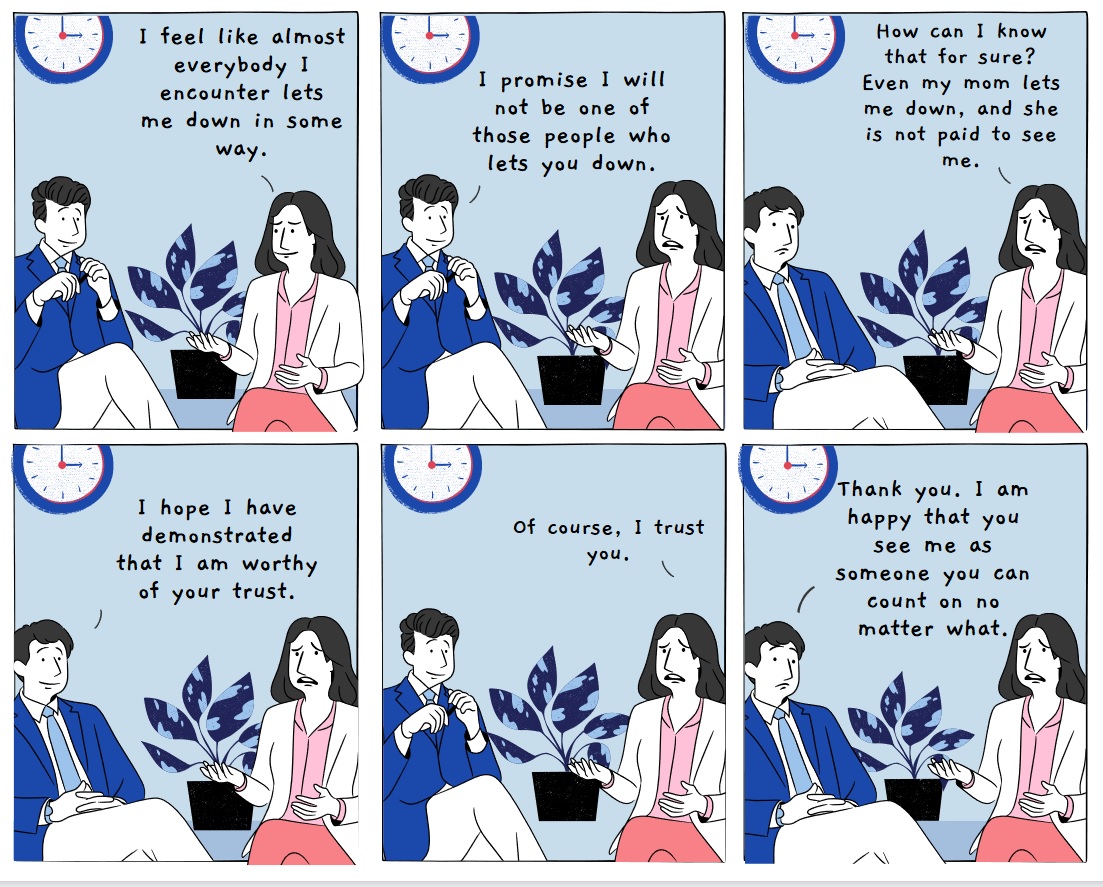

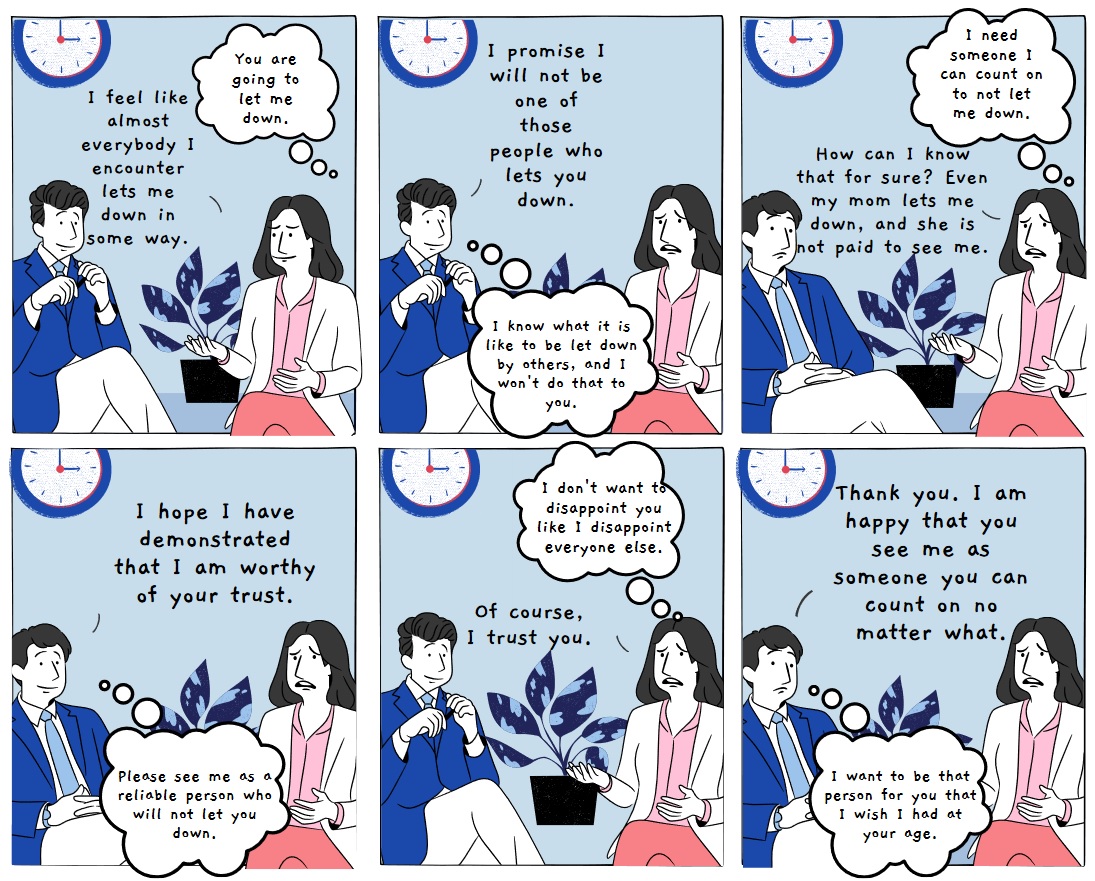

Client transference reactions and counsellor countertransference reactions are not always negative, at least on the surface, but even though they appear positive or neutral they move both individuals out of real relationship with each other (Gupta, 2017). Although it can make the counselling relationship less grounded in reality briefly, transference or countertransference in itself is not necessarily problematic. In fact, it occurs in almost all relationships, and as Paul demonstrated above, purposefully creating space for transference to occur can be part of growth-fostering therapeutic relationships within some models of counselling. However, a lack of consciousness of this dynamic, or a lack of intentionality in working with transference responses from clients, can be damaging to the client–counsellor relationship and to counselling outcomes. Transference reactions can be expressed in an overt or direct manner (e.g., anger, frustration) or they may be more covert and indirect (e.g., silence, withdrawal) (Parrow et al., 2019). Consider, for example, the following more subtle conversational exchange between counsellor and client.

Make note of your initial reactions to this dialogue, both cognitive and emotional. Then review the conversation again with the inside voices of both counsellor and client revealed.

Here is a transcript of this comic.

At first the counsellor might appear to be meeting the needs of the client in-the-moment, but notice how the conversation becomes counsellor-centred rather than client-centred as the unacknowledged transference–countertransference exchange continues. The counsellor projects onto this conversation their own needs and past experiences. Consider how this conversation may have differed if the counsellor had responded with client-centred care and empathy from the outset by choosing one of these responses:

- You are left feeling like you can’t rely on the people in your life to be there for you. [reflecting meaning]

- What is it like for you to feel like you can’t rely on the people in your life to be there for you? [questioning]

- I can see your shoulders slump as you talk about your disappointment in people. [immediacy].

It may also be important, when transference occurs, to engage in conversation directly with clients about what is going on for them in-the-moment (Parrow et al., 2019):

- I sense that you are angry. [reflecting feelings]

- Perhaps we should pause and talk about what is going on for you right now. [providing transparency]

- How are you feeling about the direction of this conversation? [checking perceptions]

- What would prefer to focus or work on right now? [questioning]

- I welcome feedback from you about our conversations. Sometimes I may misunderstand or say something that doesn’t sit well with you. [providing transparency]

Recall the research by Soto and colleagues (2018) on therapist multicultural competence discussed in Chapter 8. Client ratings of therapist cultural competence were strongly correlated with counselling efficacy; however, therapist self-ratings were not. This outcome reinforces the need for a client-centred lens on what works or does not work in both relationship-building and counselling practices. It also highlights the risk of assuming that your intentions are coming across clearly to clients. Gupta (2017) spoke of her own initial positive countertransference with one client that was grounded in a sense of cultural similarity with the client; later she discovered that the client perceived the relationship between them as culturally distance. The point here is not to mistrust your relational competency, but rather to continually check out your perceptions with clients to avoid misunderstandings or unfounded assumptions, even positive ones. Parrow et al. (2019) advised counsellors to recognize that some degree of countertransference is natural and expected in counselling conversations; however, it is very important for counsellors to minimize such potential harm to clients through education, supervision, consultation, self-care, or other professional development processes (Parrow et al., 2019).

Contributed by Dr. Lisa Gunderson

In this third video by Dr. Lisa Gunderson, she picks up on the themes of racism and privilege to explore the concept of white fragility. She positions white fragility as a barrier to effectiveness for white counsellors if they are not able to own their privilege. She also speaks to IBPOC counsellors about how to navigate white fragility in their professional relationships.

© Lisa Gunderson (2021, February 9)

If you identify as white or Caucasian, take a moment to position yourself on the scales introduced by Dr. Gunderson in this video:

1. What defence mechanism(s) do you recognize in your own beliefs and attitudes?

-

- You don’t know me.

- You’re playing the race card.

- That was not my intention; that’s not what I meant.

- I have suffered too.

- I don’t feel safe.

- I am not all “white people.”

2. What are your rules of engagement?

-

- Use a proper tone.

- Speak to me privately.

- Speak to me indirectly.

- Acknowledge my good intentions.

- Allow me to explain myself.

- Do not give me feedback.

- Other

How might these defence mechanisms and rules of engagement find expression in your relationships with clients or potentially lead to ruptures in the therapeutic alliance? What do you need to do now to address your tendency towards white fragility?

If you identify as IBPOC, to what degree do you resonate with these questions in times when you struggle to navigate white privilege and white fragility?

- Did what I think really happen?

- Was it an intentional or unintentional slight?

- If I confront the person, then what are the consequences?

- Others?

How might you address the racial battle fatigue you have experienced, yourself, and with your IBPOC peers?

What are the implications for counsellors of failing to process actively, intentionally, and honestly the issue of white fragility in terms of their ability to work effectively with all clients?

Preventing and mitigating alliance ruptures

Consider the following client–counsellor story.

You are meeting a new client for the first time. You are in your third month of your practicum, and you are really excited to be mentored by a woman who has been practicing solution-focused therapy for over 20 years. You are about to meet a young woman named Aamira. You have “googled” her name, so you know there is a possibility she is Muslim. When you go to the waiting room, she is wearing a hijab and is accompanied by two other women who stand up to follow you into the counselling session.

Aamira has listed depression and anxiety as her presenting concerns. She says that she is struggling to find meaning in her life. She is employed as an esthetician, although she has been working fewer hours over the last few months, because of her state of exhaustion. She is accompanied by her sister and her first cousin. In the first session you explore Aamira’s history of emotional distress, her medical history, her sources of social support, the stressors and challenges in her job and personal life, and the specific symptoms she is encountering. She is engaged, but somewhat distant.

You have a sense that you are not getting the whole picture from her, but it seems important to provide her with a sense of hope and expectancy about the counselling process to ensure that she returns for the next session. You invited her to consider the miracle question: “Suppose tonight, while you slept, a miracle occurred. When you awake tomorrow, what might you notice that would tell you life had suddenly gotten better?” Aamira listens intently. She then turns to her companions and seems to discuss the question with them in Arabic. You ask if there is anything she or her companions want to clarify, but she shakes her head. She seems reticent to respond, however, so you suggest that she think about this as a homework activity this week. You provide her with a workbook that your supervisor has created to guide her through the miracle question homework. You state that you look forward to seeing her next week, either with or without her companions.

Aamira shows up a few minutes late for her second session, and she doesn’t look you in the eye when she arrives. She appears to be on her own this time. You welcome her and ask a few questions about her week before checking in with her about her homework. She says that her week was fine and that her sister and cousin are waiting outside for her. She just wanted to return the workbook you gave her. You notice that she has not filled in the exercises. You can tell she is uncomfortable. You thank her and gently remind her that she is welcome to leave at any time, but you extend an invitation for her to talk with you about whatever is bothering her. She gets up and comes back a few minutes later with her two companions. One of them takes the chair directly facing you and says, “Why is there no Muslim counsellor here who can see Aamira? We make up the majority of people in this neighbourhood.”

There appears to have been a rupture in the relationship with Aamira, but the story has been left deliberately vague so that you can choose which direction to take in your reflections. Drawing on the concepts, principles, and practices that we have introduced throughout this ebook, consider how you might have avoided the relationship rupture and what you might do at this point to mitigate the situation.

- What assumptions have you made about Aamira’s statement that she is struggling to find meaning in her life? How might these assumptions reflect your own values or biases?

- What was your gut reaction to the first encounter with Aamira and her family? What elements of your value system (not necessarily cultural biases) may have been reflected in your responses?

- How might these values have influenced how you managed the first session with Aamira?

- How successful were you in establishing an egalitarian relationship and engaging Aamira in constructive collaboration?

- What are your cultural or other hypotheses about what happened in this story?

- What next steps might you take based on your learning throughout this chapter and in the rest of the ebook?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#preventingruptures. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

2. Values Differences or Conflicts

Alliance ruptures can also arise through values differences or conflicts between counsellors and clients (Collins & Arthur, 2018; Herlihy et al., 2014). Values differences or conflicts “reflect tensions between two or more values that are perceived to be incompatible or discordant” (Collins, 2018b, p. 1039).

As a counselling psychologist, I often explore values with clients. By doing so they seem to have a better understanding of themselves, their distress, and therapeutic directions. Further, values exploration may get closer to the heart of the struggle. Values exploration might also uncover client strengths and resilience. For example, I ask questions such as:

- What are some of your core values?

- Where does this value of “___________” come from?

- What does this interaction tell you about what you value?

- How has this value served you in your relationships (or work, parenting, etc.)?

I also need to be cognizant of my own values. Consider the following story of my work with a heterosexual couple, throughout which I had to make active choices to avoid potential values conflicts with my client.

During one session the man (Troy) said, “When I come home, I expect the house to be clean and dinner made.” The woman (Betty) responded, “How is that fair, when we both work full-time?” I then asked Troy about how he sees gender roles. He asserted the importance of traditional gender roles at home, because he saw his mom taking care of the house in her role as a “homemaker.” Betty piped in to say that her parents shared the household chores. She works as a business manager, and it not fair to expect her to be solely responsible for the housework. I then explored what they each value in the relationship. They indicated that, when things are going well, they value their friendship and their ability to laugh together.

During this conversation, I had to be aware of my own values related to equality and partnership. I was very careful to ensure that I asked questions for the purpose of understanding instead of using inquiry as a foundation from which to judge Troy for his more traditional views of marriage. If I had not consciously made this choice to bracket my own values, they could have noticed, and Troy could have been more likely to check out of the counselling process.

Values exploration, both within ourselves as counsellors and with clients, can be multilayered and lead to a deeper understanding of assumptions, contexts, interpersonal dynamics, and so on.

Gina

In most cases where values conflicts occur, culturally and relationally responsive counsellors are able to set aside their personal beliefs and assumptions in favour of staying present to the client’s lived experiences. This relational practice involves critical reflection on counsellor values and conscious choices not to impose them on clients (Collins & Arthur, 2018; Canadian Psychological Association, 2017; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016).

What is really the problem?

Place yourself into the following scenario, which is a true story from Sandra’s counselling practice.

I recall an encounter with a client a few years ago who used the word “fuck” in every sentence, sometimes more than once. Although I am not normally reactive to anyone’s choice of how they want to express themselves, I found myself feeling a bit uncomfortable because of the loudness of his voice. I was aware of the possibility that a colleague might overhear him. In that moment I had to step back and ask myself the following questions:

-

- Is this reaction I’m having really about him or about me?

- What message am I sending about his freedom of expression, the safety of this space, my stance of nonjudgement, and so on, by asking him to change his behaviour?

- What effect might that have on our working alliance?

- What message is he communicating to me through the strength of his language?

These self-reflective questions helped me to check my own feelings and to acknowledge that my reaction was about me being embarrassed, not about him doing something that was inherently problematic or wrong. From within his way of experiencing the world and his social context, his language use reflected a common way of expressing the depth of feeling associated with his experiences.

Fortunately I did not shut down his way of expressing his strength of emotion, and my position of nonjudgement and lack of reactivity helped to build our relationship. After a couple of sessions his communication style shifted, perhaps because he realized I was hearing him without his use of consistent strong language to emphasize his emotion, or perhaps he had another reason for the change in style. The point is that we must continuously be aware and reflective about our own values and be cautious not to impose our values on our clients.

Drawing on this scenario, work through the following questions for reflection:

- In what ways might you proactively address the potential for values conflicts with clients in order to avoid imposing your values on them?

- Under what rare conditions might it be important to address directly a values conflict with a client? In other words, what client values might you be unable to treat with respect and nonjudgment?

- How would you discern when it was important to address counsellor–client values differences directly with a client (versus addressing these as part of your own continued competency development)?

- When client values appear to impede their health and well-being, how might you invite clients to consider their own values’ positioning as part of the counselling process?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc12/#reallytheproblem. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

We have encouraged you throughout this ebook to bring your beliefs and values into conscious awareness and to be aware of their position within dominant and nondominant sociocultural discourses, so that you are freed up to hold them tentatively as contextualized lenses on reality rather than as truths. However, navigating values differences and avoiding relationship ruptures becomes more challenging in the face of client prejudice or other assumptions and biases that disregard the inherent dignity of certain peoples or stand in opposition to professional codes of ethics.

Finding common ground in the face of client prejudice

Contributed by Amy Rubin

Many of you will hold cultural identities or belong to cultural communities that exposed you to risk of prejudice and discrimination. So, what happens when you encounter a client who holds these biases? In this video Amy shares her experiences as a Jewish therapist of building connection with two clients affiliated with white supremacist belief systems. As you watch this video, consider your own places of vulnerability.

© Amy Rubin (2021, April 6)

It is important to remember that power is a complex concept, and power dynamics in counselling are intimately related to client and counsellor cultural identities and social locations. Navigating a situation in which you potentially face prejudice or overt cultural oppression from a client could lead to unnecessarily relationship rupture. In both situations Amy felt that further discussion was warranted if the relationship was to go forward. This decision was informed by many considerations: her sense of physically safety, her confidence in both her and her client’s ability to have a civil conversation, her feeling that the client would not want to hurt her as an individual, and her assessment that candidly explaining her experiences of hurt and fear might offer new insight to the client.

- What is your take-away from Amy’s experience and her approach to working with these clients?

- How might her approach compliment Melissa’s earlier video on self-care in session?

- What internal and interpersonal signals might you watch for to ensure your safety, while working to avoid alliance ruptures and open opportunities for healing if possible?

- Where are your deal breakers? Are there issues, beliefs, values, actions that are so triggering for you that it might be better to refer a client elsewhere?

- What plan might you put in place now to mitigate your reactions, so that you can be more fully present to all clients?

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

A. Leaning In/Leaning Out

Leaning in/leaning out

There are times when you may be tempted to protect yourself from the suffering of others by leaning out rather than leaning in to relationship with your client. Think of a specific example in a movie, novel, news report, or a personal or professional encounter when you felt yourself pull away from another person’s or peoples’ emotional distress or story of trauma. Reflect on that pulling away response, attending to the ways in which leaning out manifests itself emotionally, cognitively, and behaviourally. Then consider the following questions for reflection:

- What are you most afraid of in terms of working with clients who have experienced violence, torture, or other forms of trauma?

- What is most likely to trigger a leaning out response in you?

- What have you learned from this chapter that might mitigate the leaning out and enable you to lean in when your clients need you most?

Come up with a list of proactive measures to minimize the risk of compassion fatigue and to support a leaning in stance?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#leaning. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

B. Enlisting Your Own Story

In this final chapter we invite you to look back over your own story through the lens of self-compassion and self-kindness.

- Where do you notice the self-critic emerging?

- In what ways have you internalized negative messages that influence how you have viewed your story?

- How does your conceptualization of the challenge you face reflect these internal and external “not good enough” messages?

- What might it be like to re-envision your story through the lens of self-compassion? What might change in the way you describe your suffering, however big or small?

- How might your vision for your preferred presents or futures and the therapeutic directions you set for yourself expand by assuming a stance of self-compassion and self-kindness?

What are the implications of your insights from this chapter for your work with clients and for your self-care commitments as a practitioner?

C. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Macey’s story Part 11

Watch the final version of Macey’s story. As you engage with her story this last time, consider what you have learned about her over the eleven chapters. What will you take away from her story?

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, April 19)

In our debrief of this video Gina reflects critically on the parallels with Macey’s story that she sees in her own life. This forms the foundation for the peer consultation process with Sandra.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 25)

Reflections:

-

- What resonates for you in this final portion of Macey’s story?

- What additional considerations might you offer up to Gina based on your learning in this chapter?

- How might you apply your lenses of self-awareness, cultural self-awareness, and reflexivity to bring yourself most effectively and responsively into the session with Macey?

- Recall the three-part framework that Michael Yudcovitch introduced in his video in Chapter 4. How might these three questions support your conversation with Macey: (a) How are you feeling? (b) What do you need? and (c) How can I support you?

- How prepared are you to hear whatever it is that Macey might choose to tell you now, next session, or in the future? What can you do to increase your preparedness to bear witness for Macey based on your learning from this chapter?

EBOOK WRAP-UP

In this final video we look back on the process of creating this ebook, highlighting what stands out for us, what was most meaningful to us, and what surprised us in the process.

© Gina Ko, Sandra Collins, & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2023, May 5)

Take a moment to reflect on what this learning experience has meant for you by considering the following questions:

- How are you different now than you were when you read the introduction to this ebook?

- What will you carry forward with you as you continue your development as a healthcare practitioner?

- What are your continuing competencies goals for the next six months as you reflect on the importance of centring relationships in counselling practice?

REFERENCES

Brown, J. (2019). Reflective practice of counseling and psychotherapy in a diverse society. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24505-4_8

Brown, L. (2020, September 2). Death by Zoom fatigue: The cost of virtualizing social interaction. https://www.mcgilldaily.com/2020/09/death-by-zoom-fatigue/

Buchanan, M. J., & Keats, P. (2015). Secondary trauma and compassion fatigue: What counselling educators and practitioners need to know. In L. Martin, B. Shepard, & R. Lehr (Eds.), Canadian counselling and psychotherapy experience: Ethics-based issues and cases (pp. 427–458). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Canadian Psychological Association. (2017). Canadian code of ethics for psychologists (4th ed.). Retrieved from http://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Ethics/CPA_Code_2017_4thEd.pdf.

Coleman, C., Martensen, C., Scott, R., & Arce Indelicato, N. (2016). Unpacking self–care: The connections between mindfulness, self–compassion, and self–care for counselors. Counseling & Wellness Journal, 5, 1–8. https://openknowledge.nau.edu/view/divisions/CWJ.html

Collins, S. (2018a). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices: Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 441–505). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018b). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S., & Arthur, N. (2018). Challenging conversations: Deepening personal and professional commitment to culture-infused and socially just counselling processes. In D. Paré & C. Audet (Eds.), Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice (pp. 29–41). Routledge.

Chokkattu J. (2020). You can now attend VR meetings—no headset required. https://www.wired.com/story/spatial-vr-ar-collaborative-spaces/

Conti-O’Hare, M. (1998). Examining the wounded healer archetype: A case study in expert addictions nursing practice. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 4(3), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/107839039800400302

DeFilippis, E., Impink, S. M., Singell, M., Polzer, J. T., & Sadun, R. (2020). Collaborating during coronavirus: The impact of COVID-19 on the nature of work. NBER Working Paper Series. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3654470

Fabre-Lewin, M. (2012). Liberation and the art of embodiment. In S. Hogan (Ed.). Revisiting feminist approaches to art therapy (pp. 115–124), Berghahn Books.

Fosslein, L., & Duffy, M. W. (2020, April 19). How to combat Zoom fatigue. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-combat-zoom-fatigue

Gupta, R. (2017). What does being an “American” look like in the therapy room? Smith College Studies In Social Work, 87(2–3), 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377317.2017.1324012

Hargons, C., Mosley, D., Falconer, J., Faloughi, R., Singh, A., Stevens-Watkins, D., & Cokley, K. (2017). Black lives matter: A call to action for counseling psychology leaders. Counseling Psychologist, 45(6), 873–901. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017733048

Hauke, G., & Kritikos, A. (Eds.). (2018). Embodiment in Psychotherapy: A Practitioner’s Guide. Springer.

Herlihy, B. J., Hermann, M. A., & Greden, L. R. (2014). Legal and ethical implications of using religious beliefs as the basis for refusing to counsel certain clients. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(2), 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00142.x

Hilton, K. (2016). The perception of overlapping speech: Effects of speaker prosody and listener attitudes. Proc. Interspeech 2016, 1260–1264. https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2016-1456

Huezo, M. (2018). Barriers can be stepladders: Practice considerations for the minority counsellor. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 304–341). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Iqbal, M. (2020, October 30). Zoom revenue and usage statistics. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/zoom-statistics/

Jackson-Wright, Q. (2020, October 14). How to beat Zoom fatigue and set healthy boundaries.https://www.wired.com/story/how-to-fight-zoom-fatigue/

Johnson. (2020, October 19). Why zoom meetings are so dissatisfying. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/books-and-arts/2020/05/16/why-zoom-meetings-are-so-dissatisfying

Jordan, J. V. (2010). Relational-cultural therapy. American Psychological Association.

Jung, C. G. (1951). Fundamental Questions of Psychotherapy. In H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler (Eds.), The Collected Works of C. G. Jung (Vol. 16), translated by R. F. C. Hull. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G., & Jung, C. G. J. (1963). Memories, dreams, reflections (Vol. 268). Vintage.

Keats, P. (2016). Witnessing the trauma of others: What is the solution to vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 305–322). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Kirmayer, L. J. (2003). Asklepian dreams: The ethos of the wounded-healer in the clinical encounter. Transcultural Psychiatry, 40(2), 248–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461503402007

Lee, J. (2020, November 17). A neuropsychological exploration of Zoom fatigue. Psychiatric Times. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/psychological-exploration-zoom-fatigue

Neff, K. (n.d.). Fierce self-compassion. https://self-compassion.org/fierce-self-compassion/

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful helping. Sage.

Parrow, K. K., Sommers-Flanagan, J., Cova, J. S., & Lungu, H. (2019). Evidence-based relationship factors: A new focus for mental health counseling research, practice, and training. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.4.04

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice competencies. Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development, Division of American Counselling Association: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=14

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Sinclair, S., Raffin-Bouchal, S., Venturato, L., Mijovic-Kondejewski, J., & Smith-MacDonald, L. (2017). Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 69, 9–24. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003

Skovholt, T. M., & Trotter-Mathison, M. (2011). The resilient practitioner: Burnout prevention and self-care strategies for counselors, therapists, teachers, and health professionals (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Soto, A., Smith, T. B., Griner, D., Domenech Rodríguez, M., & Bernal, G. (2018). Cultural adaptations and therapist multicultural competence: Two meta‐analytic reviews. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1907–1923. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22679

Stone, D. (2008). Wounded healing: Exploring the circle of compassion in the helping relationship. The Humanistic Psychologist, 36(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873260701415587

BIPOC refers to Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour. It reflects the emphasis in Canada on foregrounding First Peoples and honouring the unique cultural histories and lived experiences of Black people and other people of colour.