Chapter 5 Enhancing Connection and Exploring Affect and Embodiment

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Gina Wong, Elaine Berwald, Melissa Jay, Michael Yudcovitch, Ivana Djuraskovic, and Amy Rubin

One of the overarching themes that runs throughout this chapter is connection and disconnection. Many clients experience brokenness in relationship—with self, with others, with communities, or with society. As we learn to centre relationships in counselling practice, the client–counsellor relationship gains potential to offer clients a safer space to heal in relationship. In this chapter we invite you to enhance your understanding of the importance of exploring client emotions and embodied experiences and to develop proficiency in the intentional use of relevant microskills. Client experiences of emotion and embodiment are often intimately connected to their sense of connection to self and others. We begin by positioning connection and disconnection in the context of attachment theory. We then look at the process of developing mutual cultural empathy with clients as a foundation for safer, therapeutic connections within client–counsellor relationships. We argue that both client and counsellor relational patterns of connection–disconnection can influence the formation of growth-fostering therapeutic relationships.

Figure 1

Chapter 5 Overview

Recommended additional reading

Dupuis-Rossi, R. (2020). Resisting the “attachment disruption” of colonisation through decolonising therapeutic praxis: Finding our way back to the Homelands Within. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 8(2). https://pacja.org.au/article/71234

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

A. Growth-Fostering Relationships

We argued in the first four chapters that there is much more to effective counselling practice than matching up clients’ presenting concerns with particular therapeutic processes; in fact, this approach is now considered dated and ineffective (Norcross & Wampold, 2018). Instead we have centralized relationships as a foundation for counselling practices with all clients. In this chapter we examine the ways in which relationship disruptions, within families, communities, or nations factor into comprehensive understanding of client challenges. We then explore ways of creating relational spaces in counselling that can support growth and healing.

1. Connection–Disconnection

Collins (2018) pointed to the importance of awareness of the processes of connection–disconnection both within, and outside of, the counselling relationship. She noted feminist and relational-cultural therapy (Brown, 2010; Jordan, 2010; Lenz, 2016; Singh & Moss, 2016) as two examples of culturally responsive counselling frameworks that foreground the importance of inviting clients to attend to, and heal from, relational disruptions and disconnections at the intrapersonal, interpersonal, and systemic levels. Relational disconnection from self or others is often precipitated by both external experiences of oppression or violence and corresponding internalized oppression. Recall the video by Catherine Richardson on response-based practice in Chapter 4. She introduced four operations that perpetuate blaming victims of violence. Victim-blaming is yet another way to maintain the cultural oppression of persons and people within society by disabling, pathologizing, dismissing, or erasing their acts of resistance (McBride et al., 2017). Internalized oppression is expressed often through a sense of deep shame. Consider the argument below by Brené Brown that shame then poses a barrier to connection. With disruption, clients can find themselves in a cycle of disconnection.

Brené Brown is a professor at the University of Houston who identifies as a researcher and storyteller on the topics of courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy. In this 20-minute TED talk Brené explores the power of vulnerability. Consider the implications for facilitating growth-fostering relationships with clients.

© TED (2011, January 3)

Brené asserts that the emotion of shame and the belief that they are not worthy are significant barriers to connection for many people. Reflect first on how this assertion rings true, or not, with your own lived experience. Then consider the implications of this assertion for working with clients whose interpersonal experiences of connection–disconnection may be complicated and amplified by the layering of vulnerabilities related to their marginalization within society. What lessons might you carry forward for facilitating connection with your clients and for supporting them to build connections with others?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#shame. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

2. Attachment

The report by Norcross and Wampold (2018) on the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness pointed to attachment style as one of the emergent client factors that appeared promising, but which required further research in terms of its influence on counselling efficacy (Chapter 1). Similarly Parrow et al. (2019), in their review of evidence-based relationship factors, highlighted the importance of the bond between counsellor and client and pointed to the role of attachment theory in enhancing our understanding of the nature of the therapeutic relationship and ensuring its optimal efficacy for clients. For those of you less familiar with attachment theory, the video below provides an overview of the basic concepts and principles that have emerged from psychological research on attachment.

Attachment and relationships

As you review this video reflect on the implications of the various styles of attachment for both your ability to bring yourself into relational engagement with clients and your need to attend to the attachment style of the client in building effective therapeutic relationships.

© Sprouts (2018, May 30)

We feature Gina Wong’s work on attachment in this chapter. She has been actively involved in the Circle of Security initiative. The video below provides another lens on attachment and security as background for Gina’s exploration of the implications of attachment theory for counselling practice, coming up in the next section.

© Circle of Security (n.d.)

How might the concept of “good enough” parenting translate into “good enough” security within the context of the client–counsellor relationship?

Attachment and Relationship Building

In the first few chapters, we highlighted a number of counsellor and relationship factors that have the potential to increase the bond between counsellor and client, to communicate a sense of caring, to enhance trust, and to support a sense of safety. We also pointed to the specific relational practices and counsellor behaviours that promote the development of positive emotional connection or bond between counsellor and client (Parrow et al., 2019). However, it is also important to keep in mind that this bond is bidirectional; there are always at least two people engaged in the therapeutic relationship. Understanding both your own and client attachment styles opens the door to supporting secure, growth-fostering therapeutic relationships.

Safety and trust: Creating a holding space for clients

by Gina Wong

Gina brings immense experience to asserting the importance of connection to creating safety and trust with clients. Gina points to the ways in which our own attachment experiences as counsellors come into play in what she refers to as “being with,” attuning to our own embodiment and experience as we attune to the client.

© Gina Wong (2021, February 24)

Gina believes that, as counsellors, “We are the tool” and “The tool is the whole being of us.” Take a moment to repeat this statement to yourself. Let it sit with you for a moment. Reflect on what emerges for you as you consider this lens on the therapeutic relationship.

You may be interested in this article Gina recommends on “The Power of Being With.”

Reflection functioning and secure attachment

by Gina Wong

In this next video, Gina explores, more specifically, the idea that counsellors themselves are the tool in growth-fostering, therapeutic relationships. Drawing on attachment theory she emphasizes the importance of reflective functioning or mentalization on the part of the counsellor. She illustrates this relational practice with a client story, drawn from her work in parent–child attachment (De Roo et., 2019).

© Gina Wong (2021, February 24)

Gina defines reflective functioning as the capacity to sit outside of one’s own thoughts and feelings and to go into the thoughts and feelings (i.e., the mental state) of another. You will draw on this capacity in each of the microskills introduced in this chapter. Then in the Reflective Practice section Gina will introduce specific tools for enhancing capacity for mentalization. For now, take a few minutes to ask yourself the following questions, drawing on these videos on attachment and imagining yourself as counsellor in the story Gina shared.

- What were my experiences of attachment as a child?

- How might that experience enhance or pose challenges for building a secure relationship with myself and with my clients?

- What is my capacity for reflective functioning?

- In what ways do I attend to, or actively engage, my mentalization skills to appreciate more fully the thoughts and feelings of others?

Identity Fractures Due to Colonization

For the most part psychologists and counsellors writing about attachment conceptualize client challenges through the lens of interpersonal connection–disconnection with caregivers or significant others. However, there is an emergent critique of the attachment literature that foregrounds colonization as an intentional and systemic campaign to disrupt intrapersonal connection to self and interpersonal connection within Indigenous families and communities (Dupuis-Rossi, 2018, 2020; Dupuis-Rossi & Reynolds, 2018). Dupuis-Rossi (2020) points to the limitations of the common use of the term, attachment disruption, because it “conceals the violence of colonization by locating relational distress in individual pathology occurring within the limited and limiting social construct of the European nuclear family,” and it “obscures Indigenous sacred connections and relationships to land, culture, spirit, community, [knowledge systems,] and the interconnectivity to all our relations” (“Attachment Disruption” section, para. 1). In the video below Indigenous Advisor, Liaison, and Cultural Carrier, Elaine Berwald, speaks to the identity fractures due to ongoing colonization in her reflections on identity.

by Elaine Berwald

As you listen to Elaine talk about her name, reflect on the implications of her understanding of her Indigenous identity and attachment to community. Consider carefully the diversity of experiences of identity, identity fractures, and the impact of the interruptions to community and family lines brought about by colonization.

© Elaine Berwald (2021, April 26)

Prompts for self-reflection:

- Have you experienced a relationship fracture with an Indigenous person, a community, or a systemic framework?

- Elaine invites you to dig deeply into the campaign of colonization to understand the impact on relationships within Indigenous communities and between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

- She references the Legacy of Hope Foundation publication, Hope and Healing: The Impacts of the Residential School System on Indigenous Peoples. You may want to review the Why it Matters timeline of legislative practices in Canada that have systematically erased Indigenous people.

- How might framing colonization as a fracturing of relationships, shape your approach to working with clients?

- How might you begin to build relationships with Indigenous people and communities?

3. Empathy

Empathic understanding was one of the eight evidence-based relationship factors identified by Parrow et al. (2019) and one of the relationship factors proven to be effective in the meta-analyses reported by Norcorss and Wampold (2018). Empathy is a central component of many therapeutic models; however, it is important to cast a critical lens on what we mean by this concept, particularly in the context of client and counsellor cultural identities and social locations. Paré (2013) defined empathy as the ability to “resonate with another’s experience” (p. 60), not by imagining what that person’s lived experience might be like for you (ethnocentricity), but rather what it is like for them (client-centred practice). As with other forms of communication we explore in this resource, empathy comes to life within the relationship between counsellor and client. The counsellor can experience empathic connection with a client, but if they fail to communicate that sense of care-filled connection to the client’s experience, then their empathy will not be perceived or received by the client.

Communicating compassion and empathy

Take a moment to think about the last time another person listened to you with compassion and empathy, fully attending to your feelings. What was that experience like for you? Test your own ability to communicate compassion and empathy with a colleague, friend, or family member. You may do this with, or without, that person’s awareness. What did you observe about that interaction? What meaning did you make of your observations?

Some writers position empathy as a specific counselling microskill. We have chosen not to do this, because there are many ways to communicate empathy to clients. For example, empathy can be communicated effectively through nonverbal means such as body language, as well as verbally by reflecting back what the client has said, or through judicious use of self-disclosure. In this chapter we introduce the microskill of reflecting feelings, which is another powerful way to communicate empathic understanding of client’s lived experiences.

In some counselling models, various levels of empathy are presumed, with more advanced empathy associated with interpretation of a client’s inferred meaning or feelings (Cormier et al., 2017). The microskills presented in this chapter may be used to support the theoretical goal of interpretation. However, interpretation implies a level of expertise over the client’s lived experiences on the part of the counsellor that does not fit easily with collaborative and client-centred relational practices. The difference between contributing to shared understanding versus interpreting for clients is a subtle, but important, distinction. We argue that the client remains the expert on their lived experiences, feelings, thoughts, and behaviours. You may favour a theoretical model that integrates counsellor interpretation; however, we strongly encourage you to consider the ways in which the use of particular counselling microskills, embedded in a process of mutual cultural empathy, can support you to accomplish the intent of interpretation in a way that emphasizes client empowerment and reflects intentional collaboration with clients.

Mutual Cultural Empathy

What distinguishes empathy from cultural empathy is the counsellor’s intentional mirroring or reflection to clients of understanding, appreciation, and prioritizing of the client’s culturally embedded identities, worldviews, values, norms, and relationalities. This includes acknowledgement of, compassion for, and alliance against, experiences of cultural oppression. Attempts at expressing empathy in a way that are not so contextualized risk further marginalization of client perspectives; instead, the messages sent by the counsellor must be understood from within the client’s frame of reference or ways of knowing (Jean Baker Miller Training Institute [JBMTI], 2017; Willis-O’Connor et al., 2016). Consider the reflection below on culture-specific empathic responses based on social class.

Flexing your cultural empathy muscles: The lived experiences of working-class and poverty class people

by Fisher Lavell

If you come from a middle-class background, it is often difficult to relate to the worldview and lived experiences of people from working-class or poverty-class backgrounds. The purpose of this activity is to help you to connect with these folks and to strengthen your cultural empathy muscles.

- Think about a time in your life when you felt profoundly powerless and judged.

- Get in touch with the feelings you experienced, and try to put names to a bunch of those feelings (e.g., shame, guilt, embarrassment, frustration, hopelessness).

- Now, hold on to those feelings for a while, as you imagine going through one whole day.

- Plan out that day.

- What time would you get up if you felt that way?

- What would you do if you felt that way?

- What would you eat if you felt that way?

- Who would you want to be around?

- What would you do in order to feel better?

When you have completed this reflection, take a deep breath, and clear your mind. And say a prayer of thanks, if you pray, and if you do not, just sit for another minute and feel grateful.

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#empathymuscles. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The concept of mutual empathy derives from the feminist therapy focus on egalitarian relationships and mutuality within the client–counsellor relationship (Brown, 2010). This model assumes that when two (or more) people engage in an authentic relationship with each other, they both influence, and are influenced by, that relationship. This concept was extended in relational-cultural theory to mutual cultural empathy. Mutual cultural empathy occurs when each person in the relationship opens to deeper understanding, compassion, and mutual growth by engaging in open and authentic conversations about personal cultural identities in the sociocultural contexts of their lives (JBMTI, 2017; Jordan, 2010; Singh & Moss, 2016). One of our goals in this ebook is to invite, encourage, even implore you to open to change based on your encounters with the stories you encounter and the diversity of perspectives with which you engage.

Self-disclosure as a foundation for building mutual cultural empathy

by Ivana Djuraskovic

Ivana shares a story from her experience of growing in Bosnia as a way to illustrate her understanding of the concept of mutual cultural empathy. She talks about her use of cultural self-disclosure as a foundation for building connection and communicating cultural empathy.

© Ivan Djuraskovic (2021, April 25)

Questions for reflection:

- How do you feel about the idea of building cultural empathy through self-disclosure? How might the sharing of commonalities support a sense of shared humanity?

- To what degree might your comfort, or lack of comfort, in sharing yourself as a cultural being be rooted in, or amplified by, your own worldview, or the eurowestern worldview in which you have been educated?

- If you are not willing to share your cultural self with clients, how might this affect their willingness or sense of safety in engaging in counselling with you from within their own cultural contexts?

What if I don’t like my client?

Think of a recent transformative conversation with someone in your life. Come up with a list of key words to describe the nature of that relationship, attending specifically to evidence of mutuality. What risks, benefits, or challenges can you see as you translate the concept of mutuality into counselling practice?

It is easier to picture how this process of mutual cultural empathy will evolve with a client you like and to whom you find it easy to relate. What about Joe, Raphael, Angel, or Chien-Shiung in the client scenarios below? How natural would it be for you to experience mutual cultural empathy with each of them?

| Joe comes to counselling because he is court-mandated to attend anger management sessions. He has a history of aggressive behaviour towards female partners and, most recently, pulled a knife on his current common-law partner. Joe’s first question is what he has to do to get the court off of his back. He responds to your questions with yes or no answers wherever possible and is watching the clock for most of the session. You can sense your frustration building as Joe continues to deflect responsibility for his actions. He holds firm to the belief that his partner provokes him and is, at least, equally responsible for the mess in which he currently finds himself. |

| Rafael is working as a drug dealer at a fairly high level in your local community. He has come for counselling to deal with his frustration with certain people who work for him. He also expresses his concerns about getting caught by the police, and he wants to talk about ways that he can manage his own life and his way of dealing with issues that arise to help him stay clear of the police and to avoid drawing attention to himself. He talks about experiences in the past where his reactions have made situations worse for himself and for others, but he hasn’t been able to find a way to control those reactions. He sees them as mostly automatic responses that have to do with his history and upbringing. |

| Angel refers to herself as a dyke. She has a strong presence physically and interpersonally. She shakes your hand firmly and begins swearing the moment she sits down. You notice she has a motorbike helmet with her. She is in her late-sixties, and she has recently been told that she has terminal cancer. She has refused treatment and is working with a physician who provides medical assistance in dying. She wants to plan a big going out party at which she will terminate her life. She refers jokingly to preparing her speech for Jesus so she can give him a piece of her mind when she gets to the other side. However, she can’t seem to get her current partner onside with the idea. |

| Chien-Shiung has come to counselling through an employee assistance program. She has been off work on stress leave for several months. She describes her supervisor as overbearing and unfair. She gives a couple of examples of work situations in which she chose not to do things the way her supervisor requested, because Chien-Shiung believed she knew better. She then reacted strongly when the supervisor questioned her work and asked her to consider a different approach. She says she doesn’t know if she will come back for counselling, because she told the intake worker those examples already, and she is frustrated that you are wasting her time by asking her the same questions. |

Choose the hypothetical client (Joe, Rafael, Angel, or Chien-Shiung) you are least drawn toward. Generate ideas about how the principle of mutual cultural empathy might apply to working with that client. What barriers within yourself might you need to overcome? What commonalties, points of connection, or windows to mutuality might you draw on to facilitate the development of cultural empathy?

Note. From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc10/#whatif. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

4. Presence

In the video below Melissa Jay and Amy Rubin talk about the power of being present in our work with clients, looking at counsellor presence from a holistic perspective. Their invitation to bring yourselves fully into your encounters with clients resonates with Gina Wong’s idea of being with clients as a way of creating a safe and secure space for them to do the work that they need to do.

The power of presence in counselling

by Melissa Jay and Amy Rubin

Melissa and Amy talk about their experiences, both as counsellors and clients, of what happens when two people move into presence with each other, noting the creative work that can emerge from making space for the client to tap into what is happening for them in the moment.

© Melissa Jay & Amy Rubin (2021, February 19)

As we move into talking about affect and embodiment in this chapter, consider the connection between the counsellor being fully present and them being able to move into an embodied, feeling place with clients. Note your comfort or discomfort with these ideas. Try not to judge your responses; rather, see if you can be present to them to see what self-understanding emerges for you.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

A. Conceptualizing Client Lived Experience

1. Exploring Client Challenges

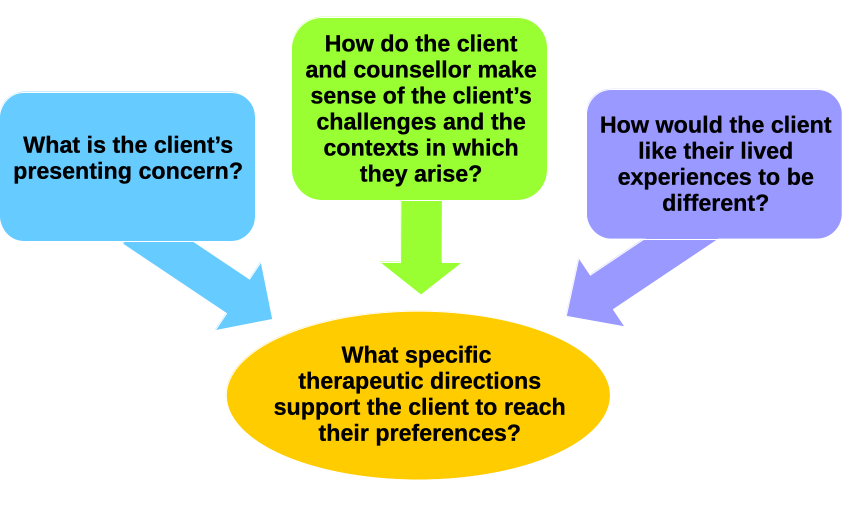

Figure 2

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

This image is described in the audio below.

In the first few chapters we focused on the question: What is the client’s presenting concern? (upper left) as we began to gather information from the client about who they are and what brings them to counselling. In this chapter we begin to examine the second question: How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise? (upper middle). In Chapter 4 we introduced various domains of experience (i.e., emotion and embodiment, thoughts and beliefs) to support a multidimensional understanding of client lived experiences. Before introducing specific microskills, we invite you to consider more fully what it means to develop an understanding of client affect and embodiment.

2. Understanding Affect and Embodiment

Holding space for clients to engage with emotions and embodiment is possible only when we, as counsellors, come to the relationship from a place of being present and embodied. If we rush into a session with clients, we may bring with us distractions from our day or stressors from our lives, or we can simply stay confined in our heads. As a result it will be more difficult to move into exploring affect and embodiment with clients. For this reason it is important to find ways to ground ourselves in the moment, in our bodies, in the relationship. Let’s revisit the discussion of ways of being in Chapter 2, attending to how we might be with clients in a feeling space.

Ways of being: Integrating mind–body–spirit–heart

by Melissa Jay

In the video below Melissa Jay draws on ways of being from both Indigenous and eastern worldviews that centralize embodiment and spirit as a foundation for connecting with clients on an emotional and embodiment level.

© Melissa Jay (2021, February 18)

Consider this quote from Melissa: “When we infuse spirit into all that we do, we are staying deeply dedicated to our why, staying deeply focused on the why of any of the doings we are participating in.” Move through the rest of your day with her final question in mind: “How am I being in this doing?”

In Chapter 8 we explore religion and spirituality as an important dimension of client lived experience and cultural identities, recognizing that this focus has often been neglected or marginalized in the theory and practice of counselling and psychology. What are the implications of omitting spirit in counselling with all clients and specifically in working with Indigenous clients? How does expanding domains of experience to mind–body–spirit–heart fit within your cultural worldview? Melissa centred feeling in embodiment and integration of heart and spirit. As you move into the exploration of emotion and embodiment in this chapter, we invite you to be open to spirit, however spirit is defined or expressed by you and your client.

One of the major themes in this ebook is the importance of taking time to build relationships with your clients and to move alongside them into whatever dimensions of their lived experience present challenges to their health and well-being. We have purposefully chosen to draw your attention to client feelings and embodiment before moving into thoughts and beliefs, because it is sometimes more difficult for counsellors to be with clients in their feelings than it is to explore what they are thinking. There are several possible reasons for why emotions may be more difficult to explore, including (a) the emphasis on the cognitive domain in many models of counselling; (b) the tendency in eurocentric worldviews, which have been paramount in the profession, to foreground and value thinking over feeling; and (c) the sense of urgency to “fix a problem” that may lead counsellors to foreclose on fully exploring client lived experiences.

Holding space for client feelings and needs

by Michael Yudcovitch

We pick up now on Michael’s focus in his counselling practice on client needs and feelings, which was where he ended his video in Chapter 4. Michael reflects on the evolution of his approach to counselling, beginning with the pressure he felt early in his career to define quickly client needs and to figure out how to help them.

© Michael Yudcovitch (2021, February 18)

Reflect on what you have learned so far in this ebook about how to build safety and trust with clients. How might you draw on these relational practices to create the space Michael positions as foundational to enabling clients to express their feelings and needs? As you continue to engage in your own learning process through these activities, we invite you to ask yourself the question Michael poses to his clients, “How will you support yourself this week?”

The ways in which feelings are experienced, named, and expressed, as well as how they are embodied, may differ substantively across cultural contexts. In Chapter 2 we encouraged you to pay careful attention to how you interpret client body language; similarly, it is important to hold tentatively to what you assume is being communicated by client emotions.

Colours in culture

Take a moment think about your favourite colour. Then list as many words as you can that you associate with that colour. What assumptions might you make if a client described a feeling or experience using your colour?

Look for your favourite colour on this Colours in Culture chart to see what words may be associated with that colour in other cultures.

Note. We do not assume the chart reflects truth; the point is to honour diversity in meaning.

Finally look up some of the words you came up with to see if they appear on the chart. What colours are associated with those words in other cultures?

Reflect on the implications of this exercise for developing shared understanding of affect and embodiment with clients.

Note. From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc5/#colours. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

The Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary provides a quick reference to each of the microskills and techniques introduced in this chapter.

A. Microskills

These microskills are specifically focused on exploring affect and embodiment with clients: reflecting feelings, inviting embodiment, and providing immediacy. One additional microskill, checking perceptions, draws attention to the importance of remaining client-centred by ensuring counsellors check in with clients to see whether their evolving understanding of client lived experiences aligns with clients’ perceptions. We will use perception checking to ensure shared understanding of other domains of client experience as well.

1. Reflecting Feelings

It is also important to be able to communicate to clients that you are attending to, and understanding (as closely as possible), what they are feeling. In Chapter 2 you were introduced to paraphrasing, which can be used to communicate to clients the feelings you have picked up on. However, paraphrasing is limited to the clients’ own words or words that are very close in nature (e.g., You are angry; I hear frustration; Annoyance). Paraphrases are particularly useful early in conversation when the focus is on communicating that you are listening and acknowledging client lived experiences. However parroting client words or using synonyms can wear thin quickly, and as a result, you can also miss opportunities to engage in deeper understandings of client feelings.

The difference between paraphrasing and reflecting feeling is the addition of novel language that invites deeper understanding of affect and embodiment (e.g., You are angry [paraphrasing]; I sense hurt underneath the anger [reflecting feeling]; I also hear some disappointment [reflecting feeling]). Often the process of incorporating a new twist or underlying feeling is referred to as adding inference. An inference is not the same as a guess (which is based on chance). An inference, on the other hand, is grounded in what you already know about the client, what you pull together in your mind from the information they have shared, what you observe from attending to their nonverbal behaviour, the connections you make from your professional experience, or your own attuned feelings and embodied responses in-the-moment. At the same time, an inference extends beyond what the client has actually said to invite deeper exploration of their feelings.

The microskill of reflecting feelings typically involves short statements highlighting a particular feeling: I hear sadness; You are feeling disappointed; I can sense your relief. When you reflect feelings back to clients, it is important to stop talking after this brief statement to allow space for the client to consider the feeling you have offered into the conversation. The hope is that your inference fits for the client, resonates with their experience, and invites further dialogue. Sometimes you will miss the mark. However if you reflect feeling in the context of a trusting and client-centred relationship, most clients will let you know why the words you chose did not fit, and they may offer alternates to move you toward a shared understanding of their feelings.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

Client: It’s been a long time since I felt confident enough to put myself out there.

|

Effectively feeling reflections are foundational to communicating empathy. Such reflections let clients know that you are with them, that you are listening to them at the feeling level, and that you are attempting to understand how they feel. They often have the effect of validating their affective experiences. There will be times when you may appropriately respond to client feelings by expressing your own affective reaction through self-disclosure (e.g., I am saddened deeply by your experience; I can feel my own frustration rising as you share your story). However, it will not be helpful to the client for you to be overcome by these feelings or to shift the attention from the client’s experience to your own. In most cases, your expression of mutual empathy will come through the language you use.

Both counsellors and clients may struggle to identify a variety of feeling words to capture effectively a wide range of affective experiences. Take a moment to list as many words as you can for different feelings. When you are finished, google “feeling words,” and review the lists that you find. How did you fare in generating a reasonable list on your own?

Reflecting feelings: Offering feeling words to promote shared understanding

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this video Sandra begins the session by drawing on some of the microskills from previous chapters to invite Gina to continue their conversation about her challenge to find balance in her life. Sandra then draws almost exclusively on the microskill of reflecting feelings to invite Gina’s consideration of her emotions related to this challenge.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 16)

As the conversation veers into Gina’s thinking patterns, Sandra struggles a bit to find the emotional vocabulary to connect with what Gina is saying. However, she continues to bring the conversation back to the underlying feelings related to Gina’s current challenges.

Moving into conversations about emotions and embodiment may be challenging for some clients, particularly for people who tend to interact with others on a cognitive level rather than on an affective level.

- Consider what other feeling words you might have offered to Gina.

- What are the risks of developing a counselling style that focuses predominantly on either affective or cognitive domains of client experiences? Consider Michael Yudcovitch’s comments earlier in the chapter. How might the cultural identities of client and counsellor come into play in your choice of domain focus?

- Reflect on the concept of mutual cultural empathy and its implications for learning to stay with clients when they introduce feelings in the conversation.

Exploring lived experience: Focusing on affect

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

As Gina continues her conversation with Sandra, she uses a variety of microskills in addition to reflecting feelings. She provides a glimpse of microskills and techniques that we will introduce later in this chapter and in the next. Notice how Gina focuses her questioning on Sandra’s feelings as a way to enhance shared understanding of her experience in this domain. We encourage you to pause the video if you are unsure about how we have labelled a particular microskill and review the Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 16)

Notice how Gina’s choice of microskills and the language she used kept the focus on the affective domain. She opened the door to hear more about how Sandra was feeling. If you struggled to come up with additional feeling words, revisit the list you generate earlier to see which ones might fit. There was one point in the video where we identified paraphrasing rather than reflecting feelings. Paraphrasing very closely mirrors the language used by the client, in this case the feeling words that Sandra had just expressed. In other places where Gina reflected feelings, she used her own words to add a different twist or to infer a slightly different feeling in response to Sandra’s description of her lived experience.

One of the keys to reflecting feeling is to keep your statements short (e.g., Simon, I hear a sense disillusionment; You seem to be feeling hurt). If you keep talking once you have offered up a feeling word to the client, you may end up moving away from the focus on affect. For example, you might say: You are feeling disappointed because you trusted him, and he didn’t follow through. Adding why the client feels a certain way may lead them down the path of focusing on the reasons behind an experience rather than their feelings about the experience. Or you could respond with I can sense a wee bit of optimism, but then it seems like you don’t really believe what he is saying, and this reinforces your assumptions about how things will play out. In this case, Simon might lean into his beliefs and assumptions rather than his feelings. In both of these cases, you have distracted the client from the affect or feeling focus. In the context of the applied practice activities later in the chapter, these statements would not be considered clear examples of reflecting feeling.

2. Checking Perceptions

Particularly in the early stages of developing a relationship with clients, it is easy to misunderstand what clients are telling you, because you each bring your own personal, historical, cultural, and contextual lenses to the conversation. It takes time to develop a shared understanding of client values, worldview, lived experiences, and so on. Perception checking is an important way of being tentative about your attempts at communicating understanding and inviting moment-by-moment feedback from the client.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement or question |

|

|

|

Checking Perceptions

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

Sandra continues her previous conversation with Gina in this video, shifting the focus now to the heaviness Gina is experiencing as a BIPOC person. Notice the how Sandra draws on checking perceptions to communicate a tentativeness in her reflecting of Gina’s feelings. Sandra’s intentional tentativeness around the word self-doubt offers Gina permission to say that Sandra’s feeling reflect was not a good fit for her.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 16)

Sandra uses a variety of approaches to checking perceptions (shifting her wording). Take a few minutes to generate a list of short phrases that you might use in your conversations with clients or in the applied practice activities at the end of this chapter. Some of the words that Sandra used to reflect Gina’s feelings could also fit in the cognitive domain, self-motivated for example. We address the challenge of staying focused on affect and generating feeling words after the next demonstration of checking perceptions below.

Checking Perceptions

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this second video on checking perceptions, Gina integrates checking perceptions to ensure that the feeling words she is suggesting are a good fit for Sandra.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 2)

What other feeling words might you have used in response to Sandra? Add any new ideas for ways to word checking perceptions to you list.

Staying focused on emotion

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this video Sandra struggles a bit to bring Gina’s attention to the feelings she is experiencing. Notice how Sandra checks out her perceptions a couple of times to ensure that the feeling words she introduces into the conversation are a good fit for Gina.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, February 9)

Sandra and Gina debrief the video above, focusing on the challenges that may arise in moving into the affective domain with some clients.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, February 9)

Take a moment to check out the feelings wheel. Then reflect on those feelings you are most comfortable expressing and those you tend to shy away from. You may want to print a copy of the feelings wheel for your applied practice activities.

Consider also the sociocultural construction of feeling, both the words that are used for different emotions across various cultures (and not well captured in English) as well as the ways in which feelings are embodied or expressed. How might you avoid projecting your cultural identities and social location onto client experiences in the affective domain?

3. Inviting Embodiment

You can encourage clients to talk about feelings by supporting them to shift their focus from their mind to their body, which in some cases may be outside of their normal comfort zone. The microskill of inviting embodiment aims specifically at drawing attention, gently and respectfully, to the ways in which emotions are experienced in, or expressed through, the body.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement or question |

|

|

|

It is challenging for counsellors to invite clients into an embodied experience if they themselves are in a state of disembodiment. We have integrated videos, particularly those by Melissa Jay and Amy Rubin, throughout this resource to remind you to bring your whole selves into the counselling process. By doing so you create space for clients to also experience themselves from the mind–body–spirit–heart place into which Melissa invited you earlier in the chapter.

Inviting embodiment: Locating feelings in the body

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In this video Sandra focuses on the embodiment of emotion. As you watch the video, identify the microskills that are familiar. Note the preview of offering immediacy, which we will cover in the next section. Attend in particular to the ways in which Sandra extends her invitation to Gina to locate feelings in her body, both verbally and nonverbally.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 16)

What do you notice about Gina’s engagement with her feelings as Sandra draws her into the process of embodiment?

Inviting Embodiment

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this next video Gina uses the skill of inviting embodiment to support Sandra to explore the ways in which emotions are held in her body and what the embodiment of those emotions tells her about her affective experience.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, February 9)

Take a moment to attend to your body. What do you notice in this moment? What feelings do you associate with these sensations or other embodied experiences? If you struggle to identify embodied experiences, take a moment to do some deep breathing; then try again. If you struggle to connect those sensations to feelings, review the feelings wheel, attending to those emotions that resonate for you.

4. Offering Immediacy

This particular microskill provides clients with feedback related specifically to what is happening in the here-and-now for the client. When offering immediacy, you may focus on one or both of the following:

- What is going on for the client themselves in the moment.

- What is going on in the counselling relationship in the moment.

The first focus may involve pointing out a change in body posture, tone of voice, or other verbal or nonverbal signals that suggest something has shifted on the part of the client: I notice that you just pushed your chair back a few inches, or You’ve become quiet all of a sudden. Alternatively the counsellor may focus on observing what is happening in the client–counsellor interaction in that moment, including the client’s engagement in the process: I feel like I missed the mark with my last statement, and you seem a bit disconnected from our conversation. These observations of the process serve the purpose of providing clients with further feedback that can engage them in the process and encourage further self-exploration or self-awareness on their part. In each case it is the embodiment of client emotions or responses that the counsellor is exploring.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

|

We use the language of offering immediacy to communicate that counsellor observations are offered up tentatively for client reflection. This microskill is sometimes referred to in other resources as paraphrasing nonverbal communication or process observing.

Offering immediacy

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

The following video is a continuation of Sandra’s conversation with Gina about the heaviness she sometimes experiences in her anti-racism work. Notice the microskills from previous weeks that Sandra uses to connect with Gina relationally and focus on her feelings. As you watch the video attend to Gina’s nonverbal behaviours, watching for opportunities where you might comment on nonverbal shifts in posture, use of her hands, tone of voice, or general presence.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 16)

How did Sandra’s attention to Gina’s nonverbal behaviours align with your observations? What would you have done differently? What else seemed important in Gina’s nonverbal cues that might have deepened her self-awareness of her emotions. The technique of co-creating language will be introduced in Week 6. Notice again that Gina does not relate to the word exhausting; however, her feedback to Sandra helps them both come closer to a shared understanding of her lived experiences. Don’t be afraid to offer up potential language to the client; instead attend carefully to the times when it does not resonate with them and invite further conversation.

Offering immediacy

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

Gina invites Sandra to talk about a project about which she is excited, which offers Gina an opportunity to observe how Sandra’s energy is expressed through Sandra’s nonverbal behaviour. Consider what it may have been like for Sandra if Gina had simply attended to her verbal, while ignoring her nonverbal, self-expression.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 2)

How comfortable might you be in offering feedback to clients on their nonverbal behaviour? What might contribute to you holding back and staying focused only on verbal interactions? How might you increase your comfort level in this area?

Commenting on shifts in client posture, affect, and other forms of nonverbal communication can be a powerful way to bring a client’s attention to what is happening in the here-and-now, or to bring into awareness a potential incongruence between what the client is saying and what their body language is communicating. In the skills synthesis section below we provide additional examples of the microskill of offering immediacy.

5. Skills Synthesis

Chapter 5 skills synthesis

In this video Sandra talks with Gina about the emotions Gina is feeling because the pandemic prevents her from spending time with her new nephew. Notice how Sandra integrates each of the counselling microskills introduced in this chapter to give you a sense of how they can work together to support co-construction of shared understanding of affect and embodiment. Be sure to pause the video when prompted to identify each microskill to reinforce your ability to discern among them.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, February 9)

Clear and Concise Microskills

Using clear and concise microskills is an important strategy for ensuring effective communication with clients. For the most part, Sandra and Gina keep their counsellor verbalizations clear and concise so that the message is clear to the client. When counsellors ramble or string together multiple ideas in a single sentence, clients may begin to tune out or become frustrated with the conversation. Listen to the audio demonstrations below to get a sense of what happens when the counsellor’s skill use is convoluted and complex.

If you were the client, how would you respond to each of these counsellor verbalizations? How much easier would it be for you to engage in the conversation if the counsellor used clear and concise microskills? As you engage in your applied practice activities later in the chapter, pay attention to keeping your counsellor statements short so that the meaning and intent is clear to the client.

B. Techniques

In some chapters we include techniques based on the relational concepts, principles, and practices introduced. The technique of practising grounding is not part of the applied practice activities; however, we encourage you to try out some of these activities on your own.

1. Practising Grounding

Practising grounding is introduced in this chapter for two reasons. Firstly some clients may struggle to get in touch with their emotional experiences, in particular to connect to what is happening in their bodies. This can be especially true for clients who have experienced trauma for whom disconnection from emotion and embodiment may have served them well in coping with their experiences in the past. It can also be the case for clients who tend to race around in their minds and place little attention on experiences outside of the cognitive domain. Grounding exercises can support clients to be present to themselves and to the therapeutic conversation and relationship, and supports them in developing a sense of safety in the here-and-now. Secondly we are strongly encouraging counsellors to bring themselves in wholeness into their relationships with clients, which necessarily means getting touch with their own emotions and embodied experiences.

I have always done some sort of grounding activity prior to welcoming clients. For me it is a way of transiting into the shared space and leaving behind or setting aside whatever pressures or distractions accompany me that day. The process of making tea for clients is part of my grounding, transitioning rituals. I add breathing exercises when I feel more scattered. I have always kept a selection of objects in my office for client use as grounding tools. A basket of smooth rocks of various shapes, sizes, and colours offers clients something to hold in their hands to help bring them into the present. For some clients taking a rock home or back to work in their pocket supports them to remain calm and centred throughout the rest of the day. There is always a cozy blanket nearby, rarely used by most clients and always used by others. Other tactile and calming visual stimuli support us to both come into the space together in as much wholeness as possible.

Sandra

| Description | Purpose | Steps/Processes |

|

|

|

The following is a sampling of activities that support the process of coming to the present and connecting with emotions and embodied experiences. There are many other options that can accomplish the same goal. It is important to attend to client cultural norms as you select an appropriate grounding practice, in particular if you and your client are not from the same cultural background. Dupuis-Rossi and Reynolds (2019) speak to the importance of culturally relevant grounding as a way for Indigenous therapists to support Indigenous clients who have been traumatized as a result of colonization and who experience dissociation. The use of culture-specific grounding processes supports Indigenous clients to experience a sense of internal safety in the here-and-now. Such practices would not be appropriate for use by non-Indigenous practitioners. However, as part of responsive relationship-building, you may invite clients to identify practices that fit for them and tentatively introduce your own ideas for their consideration.

Opening to emotions and embodiment through grounding practices

We have chosen a couple of examples of grounding activities for your consideration. Attend to which ones you gravitate toward and why that might be the case for you. As with any activity or practice you access through the Internet, it is important to be discriminating and to cast a critical eye on embedded values and assumptions. There is a wealth of resources, each of which should be assessed critically for its professional fit and for its responsiveness to the culture and social location of the clients with whom you work.

© Heather Evans Coaching (2019, October 17)

© Sunnybrook Hospital (2020, October 5)

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

A. Enhancing Reflective Functioning

Our intention in this ebook is twofold: (a) to increase your self-awareness and capacity to engage in reflective practice, in order (b) to enhance your ability to engage in care-filled, culturally responsive, and client-centred relationships with all clients. Let’s pick up on the concept of reflective functioning or mentalization introduced by Gina Wong earlier in the chapter. There is growing evidence that therapist capacity for reflective functioning can be enhanced and that increased capacity for reflective functioning positively influences therapist efficacy and their own sense of well-being (Brugnera et al., 2020; Ensink et al., 2013). Exploring and supporting narrative coherence is one of the processes associated with enhancing reflective functioning.

Narrative coherence: Building a foundation for empathy

Contributed by Gina Wong

In her earlier videos in this chapter Gina introduced the concept of reflective functioning or mentalization as critical to counsellor capacity to experience empathy for clients (i.e., to appreciate their mental states). She connected reflective functioning to the counsellor’s own attachment style. In this video she emphasizes the malleability, through personal and professional development work, of the counsellor’s own sense of secure attachment and their ability to engage in reflective functioning.

© Gina Wong (2021, February 24)

Gina invites you to embrace this opportunity for growth as a counsellor by reflecting on the coherence of your own personal narrative, leaning in with honesty, self-compassion, and nonjudgement as you would with your clients. We will continue with this theme as you enlist your own story in the next section.

B. Enlisting Your Own Story

Drawing on your learning throughout this chapter, and more specifically the videos by Gina Wong, we invite you to apply the principles of reflective functioning as you continue to explore your own story. Counsellors share a belief that human beings have tremendous capacity for growth and healing. You have the opportunity to offer the type of reparative relationship to yourself (and others) that can facilitate the earned attachment Gina spoke of in her final video. As you continue to work with your own story initiated in Chapter 1, take some time to reflect on the coherence of your narrative, drawing on some of the questions Gina posed in the video.

- How does your narrative of growing up hold together?

- How do you make sense of your story?

- Who provided you with a sense of relational security: your parent(s), your caregiver, or other significant adults?

- What gaps or holes do you notice in your story?

- How clear are your memories? What might be missing?

- Who was there to mirror your emotions or validate them?

- Does your story unfold coherently, or is it challenging to see how bits and pieces fit across time?

As you reflect honestly and without judgement on your story, applying a lens of relational curiosity, what do you wonder about? What meaning do you make of the degree of coherence you observe? Identify the principles, concepts, and practices from this chapter with which you resonate as you reflect on how you make sense of your upbringing and how your story may influence the personal challenge you explore from chapter-to-chapter in this ebook.

The value of counselling as a part of personal and professional development

As you listen to the experiences and stories from many of the contributors in this ebook, you will notice that they are also engaged in counselling as clients, either during specific times in their lives or as an ongoing practice. As authors, we also value the opportunities we have to do our own personal and professional work through our own counselling. Engaging in therapy not only supports counsellors’ health and well-being, allowing them to bring their whole selves more fully into relationship with clients, but also provides them with insider understanding of the counselling process. This insider information allows them to extend the process of reflective functioning to appreciate the experience of being a client in the client–counsellor relationship. We invite you to consider how you might benefit personal and professionally in this way.

C. Engaging with Client Stories

Macey’s story: Part 5

As you watch Part 5 of Macey’s story, consider the themes related to emotion, embodiment, and attachment that run through this chapter.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, March 18)

Sit quietly for a moment to reflect on your emotional and embodied responses to Macey’s story. What resonates with you? What do you become curious about? What questions arise for you about how to move forward as Macey’s therapist?

In our video debrief below Gina positions herself as Macey’s therapist and invites Sandra to provide her with feedback in a peer supervision and consultation process.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 20)

If you were given an opportunity for peer consultation as Macey’s therapist, what questions would you want to bring forward to your peers?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

If you can work with a different peer to complete the applied practice activities, this might be a good time to pick a new partner. If you do switch partners and you do not have an established connection, take some time to connect outside of the applied practice activities to build a relational foundation before starting these activities. The activities in Chapters 5, 6, and 7 move into multidimensional exploration of client lived experiences, beginning with a focus on emotions and embodied experiences explored in this chapter. You may want to print out the Chapter 5 Applied Practice Activities before you begin your practice session. The

A. Responsive Microskills

Preparation

You will support your partner’s practice of the microskills introduced in this chapter by choosing a topic that facilitates exploration of emotion and embodiment. Remember, however, to select a topic that will allow you to avoid introducing traumatic experiences or disturbing emotions.

Please prepare in advance to talk about a challenge in your life that is related to, or influenced by, experiences of relational connection–disconnection. You may want to focus on one or more of these dimensions: (a) intrapersonal (i.e., struggles with wholeness of self), (b) interpersonal (i.e., challenges in relationships), or (c) systemic (i.e., relationship to community or society as a whole). Consider in advance your level of comfort in talking about your own attachment style, challenges in connections with others, or experiences of fractures (internal, familial, or community) due to colonization or other forms of cultural oppression. The activities below provide an opportunity to reflect on these influences on who you are as a cultural being and a counsellor. However you are always in charge, as the client, about what you choose to share or not share. Pay close attention to your internal state, and let your partner know if you want to stop talking about something, or that you need a break.

You will begin to lengthen the time of each practice round, so that you become comfortable with longer intentional conversations. For the applied practice activities in this chapter, please spend 8–9 minutes each in the counsellor roles.

1. Warm-Up Activity: Authentic Conversations (30 minutes)

Preparation

Choose an experience from your week that brought you joy, excited or motivated you, or left you feeling affirmed, encouraged, or supported. The intent of this activity is start moving in the direction of exploring emotions with each other. Come prepared with a copy of the feelings wheel that Gina Ko uses in her practice. This wheel can help you identify words to describe your emotions.

Think ahead to common idioms or expressions on which people often draw when they are uncomfortable with emotion (e.g., I know how you feel. Nothing bad lasts for ever. You still have your health. Words fail me. Time heals all wounds). You will want to avoid such closed statements during the first exercise.

Skills practice (4–5 minutes each)

You do not need to record this practice activity.

- Client: Describe the experience, without stating how you felt (feel) about it.

- Counsellor:

- Use questioning or probing to elicit more information about the client’s experience, focusing on their feelings.

- Use the microskill of reflecting feeling, following the response from the client, to add an additional feeling word that seems like a good fit for what the client is experiencing. The purpose is to express empathy and to deepen understanding of their feelings.

- Client: Give the counsellor a thumbs up or thumbs down based on how well their choice of feeling word resonates with you, but do not discuss your assessment with them.

- Counsellor:

- Try out other feeling words, drawing on the feelings wheel, as necessary, until you get a thumbs up from the client.

- Then use questioning or probing to find out more about the experience, and repeat the process by reflecting feeling, starting with a new feeling word.

Continue directly into the second part of this practice activity.

Skills practice (2–3 minutes each)

- Client: Continue to talk about the topic.

- Counsellor: Instead of reflecting feeling, draw on one of the common idioms or expressions you noted ahead of time, or make a similarly trite statement to the client.

- Client: Give the counsellor a thumbs up or thumbs down based on how well their choice of feeling word resonates with you, but do not discuss your assessment with them.

Reflective practice and feedback

- What was it like to receive a thumbs up or thumbs down as you made inferences about the client’s feelings? How was this helpful or not helpful in co-constructing shared understanding?

- Contrast compassionate and empathic reflection of feelings with the use of common idioms, from both counsellor and client perspectives.

2. Exploring experiences of disconnection (30 minutes)

Skills practice (8–9 minutes each)

- Client: Introduce a challenge in your life that is related to experiences of relational connection–disconnection. Focus on your emotions (rather than thoughts or beliefs).

- Counsellor:

- Use microskills from Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 to start off your dialogue and to focus attention on client emotions (e.g., transparency, questioning).

- Then draw on the microskill of reflecting feelings to respond to the client. Keep your statements short, offering up additional feeling words to enhance your shared understanding of the client’s experience in the affective domain.

- Where appropriate, follow up your reflecting skills with checking perceptions to invite client feedback and ensure client-centred understanding.

- Near the end of your conversation, introduce the microskill of offering affirmations (from Chapter 4) to communicate empathy and foreground client resistance, strengths, or competencies.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback to each other on the skills practice goals for this activity. Remember to be specific, descriptive, immediate, and nonevaluative.

- Reflect critically on the connection between the use of these skills and (a) coming closer to a shared understanding of each other’s challenges, and (b) building connection, trust, and a sense of empathy within the client–counsellor relationship.

3. Facilitators and Barriers to Connection (40 minutes)

Preparation (together)

Discuss in advance each person’s comfort level with talking about the ways in which their experiences of disconnection may influence connection-building with others, particularly clients. Before you begin the skills practice reflect explicitly on the ways in which power dynamics and social location (Chapter 4) may enter your relationship as peer partners. If either of you chooses not to proceed with this topic, select a different topic that supports engagement with emotion from within your comfort zone.

Skills practice (8–9 minutes each)

- Client: Continue to talk about your experiences, opening the door to a conversation about challenges and facilitators to building connections (or an alternative topic).

- Counsellor:

- Draw on the microskills of reflecting feeling and checking perceptions in your responses to build a shared understanding of the emotion underlying this experience.

- Pay attention to any tendency on the part of the client to explain, critique, or otherwise shift into thoughts and beliefs. Draw on microskills from Chapter 2 and Chapter 3 to maintain the focus on client emotions.

- Look for an opportunity to invite embodiment to shift the conversation from describing emotions to appreciating the ways in which the client holds those emotions in their body.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How challenging was it to stay focused in the feeling domain? What specific barriers did you encounter? How might you overcome these?

- What did you learn about your patterns of connection–disconnection through the focus on emotion and embodiment? What might have been missed by a focus on only thinking?

4. From Empathy to Mutual Cultural Empathy (50 minutes)

Preparation

Draw on one of the scenarios from the What if I don’t like my client? learning activity (earlier in the chapter), or imagine a scenario in which you might find it difficult to feel or express mutual cultural empathy with a client. If you choose a client with whom you have worked, please be very careful not to share any details that would identify that person.

Skills practice (8–9 minutes each)

- Client: Talk about your fears, resistance, self-doubt, or other emotions related to connecting on an empathic level with the client you envision.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on the microskill of reflecting feelings in your initial responses to intentionally build shared understanding.

- Look for an opportunity to offer immediacy by attending carefully to the client’s nonverbal communication.

- Follow up by inviting embodiment to explore in greater depth their embodied emotions in-the-moment.

Skills practice (3–4 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- To move from empathy to mutual cultural empathy, draw on the skill of self-disclosing (Chapter 3) to share with the client an immediate, in-the-moment, emotional response to their lived experience (e.g., As you were talking, I could feel the butterflies in my stomach). Allow time for a short response from the client.

- Next use the second form of self-disclosing by talking briefly about your cultural identity, history, or other relevant lived experience. Allow time for a short response from the client.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Recall the definition of reflective functioning or mentalization (i.e., ability to appreciate client mental states, including emotions). How would you rate your current capacity to experience empathy for clients? How did the focus on emotion and embodiment influence your reflective functioning?

- How did the introduction of self-disclosure support the shift from empathy to mutual empathy? What are the implications for you in building connections with all clients, even with those with whom you struggle to connect?

5. Integrating Mind–Body–Spirit–Heart (20 minutes)

Preparation

In your role as counsellor, attend to your own embodiment in this final short dialogue. Consider the question posed by Melissa Jay earlier in the chapter: “How am I being in this doing?”

Skills practice (5–6 minutes each)

- Client: Pick up on any topic you want to discuss further from these practice activities (or the themes in this chapter).

- Counsellor:

- Draw on any of the microskills in this chapter to explore client emotions and embodiment.

- Attend simultaneously to your own emotions and embodiment.

Reflective practice and feedback

- To what degree were you able to stay present and grounded in your body as you assumed the role of counsellor in each of these practice activities?

- What shifts did you notice, if any, in this final practice round in which you were explicitly reminded to bring yourself into the conversation from a place of mind–body–spirit–heart?

6. Increasing your Emotional Vocabulary

If you struggled to reflect emotions, you may want some additional practice.

Skills practice

- Review this list of Emotionally laden statements.

- Come up with one reflection of feeling each for each statement, rotating who goes first.

Reflective practice and feedback

- What might you want to avoid when reflecting emotionally laden content back to the client?

- How might you continue to work on increasing your emotional vocabulary?

REFERENCES

Brown, L. S. (2010). Feminist therapy. American Psychological Association.

Brugnera, A., Zarbo, C., Compare, A., Talia, A., Tasca, G.A., de Jong, K., Greco, A., Greco, F., Pievani, L., Auteri, A., & Lo Coco, G. (2020). Self-reported reflective functioning mediates the association between attachment insecurity and well-being among psychotherapists. Psychotherapy Research, 31(2), 247–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2020.1762946

Collins, S. (2018). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices: Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 441–505). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Cormier, S. Nurius, P. S., & Osborn, C. J. (2017). Interviewing and Change Strategies for Helpers. Cengage Learning.

De Roo, M., Wong, G., Rempel, G. R., & Fraser, S. N. (2019). Advancing optimal development in children: Examining the construct validity of a parent reflective functioning questionnaire. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 2(1), https://doi.org/10.2196/11561

Dupuis-Rossi, R. (2018). Indigenous Historical Trauma: A Decolonizing Therapeutic Framework for Indigenous Counsellors Working with Indigenous Clients. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 275–304). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Dupuis-Rossi, R. (2020). Resisting the “attachment disruption” of colonisation through decolonising therapeutic praxis: Finding our way back to the Homelands Within. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 8(2). https://pacja.org.au/

Dupuis-Rossi, R., & Reynolds, V. (2019). Indigenizing and decolonizing therapeutic responses to trauma-related dissociation. In N. Arthur (Ed.), Counseling in cultural context: Identity and social justice. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Ensink, K., Maheux, J., Normandin, L., Sabourin, S., Diguer, L., Berthelot, N., & Parent, K. (2013). The impact of mentalization training on the reflective function of novice therapists: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 23(5), 526–538, https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2013.800950

Jean Baker Miller Training Institute. (2017). The development of relational–cultural theory: Self-in-relation. https://www.wcwonline.org/JBMTI-Site/the-development-of-relational-cultural-theory

Jordan, J. V. (2010). Relational-cultural therapy. American Psychological Association.

Lenz, A. S. (2016). Relational-cultural theory: Fostering the growth of a paradigm through empirical research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12100

McBride, H. L., Kwee, J. L., & Buchanan, M. J. (2017). Women’s healthy body image and the mother–daughter dyad. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 51(2), 97–113. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Parrow, K. K., Sommers-Flanagan, J., Cova, J. S., & Lungu, H. (2019). Evidence-Based Relationship Factors: A New Focus for Mental Health Counseling Research, Practice, and Training. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 41(4), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.41.4.04

Singh, A. A., & Moss, L. (2016). Using relational-cultural theory in LGBTQQ counseling: Addressing heterosexism and enhancing relational competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12098

Willis-O’Connor, S., Landine, J., & Domene, J. F. (2016). International students’ perspectives of helpful and hindering factors in the initial stages of a therapeutic relationship. Canadian Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 50(3, Supplement), S156–S174. https://cjc-rcc.ucalgary.ca/