Chapter 2 Building Care-Filled Connection

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Ivana Djuraskovic, Lisa Thompson, Melissa Jay, and Amy Rubin

In this chapter we invite you to reflect, openly and intentionally, on your contribution to responsive, client-centred, and therapeutic relationships. You may have chosen to pursue a career in counselling because of the challenges that have shaped your lived experiences. You may come with a desire to draw on your evolving strengths as a human being and your ability to feel and express empathy for others. You may aspire to enhance the lives of other people through your compassion, care, and insight. All of your experiences and qualities form a foundation for who you are as a person and a professional. The purpose of this chapter is to support you to critique, refine, and apply, with client-centre purposefulness, the counsellor factors that support ethical caring and responsive rapport-building with every client you encounter.

We define care intentionally in terms of what the client needs in each moment. The counsellor plays an important role in providing a care-filled relational process; however, what is most important is how the client experiences the counsellor and the relationship. At the core of client-centred practice is counsellor self-awareness. You may want to start a reflective journal to record your thoughts, feelings, body sensations to support continuous engagement in reflective practice as you build care-filled connections with clients.

As we noted in Chapter 1, each chapter will be organized using five main categories: (a) relational practices, (b) counselling processes, (c) microskills and techniques, (d) reflective practice, and (e) applied practice activities. In this chapter we consider how the person of the counsellor combines with an ethic of care to support responsive relationships. We expand on this conceptual foundation to examine how counsellor ways of being influence the process of building care-filled connections with clients. We also begin to introduce some specific counselling microskills to support rapport-building with clients. We wrap up the chapter by focused on the importance of counsellor self-awareness as a foundation for intentional and responsive relationship-building with clients. The following diagram provides an overview of chapter content.

Figure 1

Chapter 2 Overview

At the end of this chapter we provide applied practice activities for those who want to partner up with a peer or colleague to practice implementing the counselling microskills we introduce. The activities are designed to further your self-reflection and your learning about counselling relationships and the specific counselling processes that are the focus of this chapter.

At the end of this chapter we provide applied practice activities for those who want to partner up with a peer or colleague to practice implementing the counselling microskills we introduce. The activities are designed to further your self-reflection and your learning about counselling relationships and the specific counselling processes that are the focus of this chapter.

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

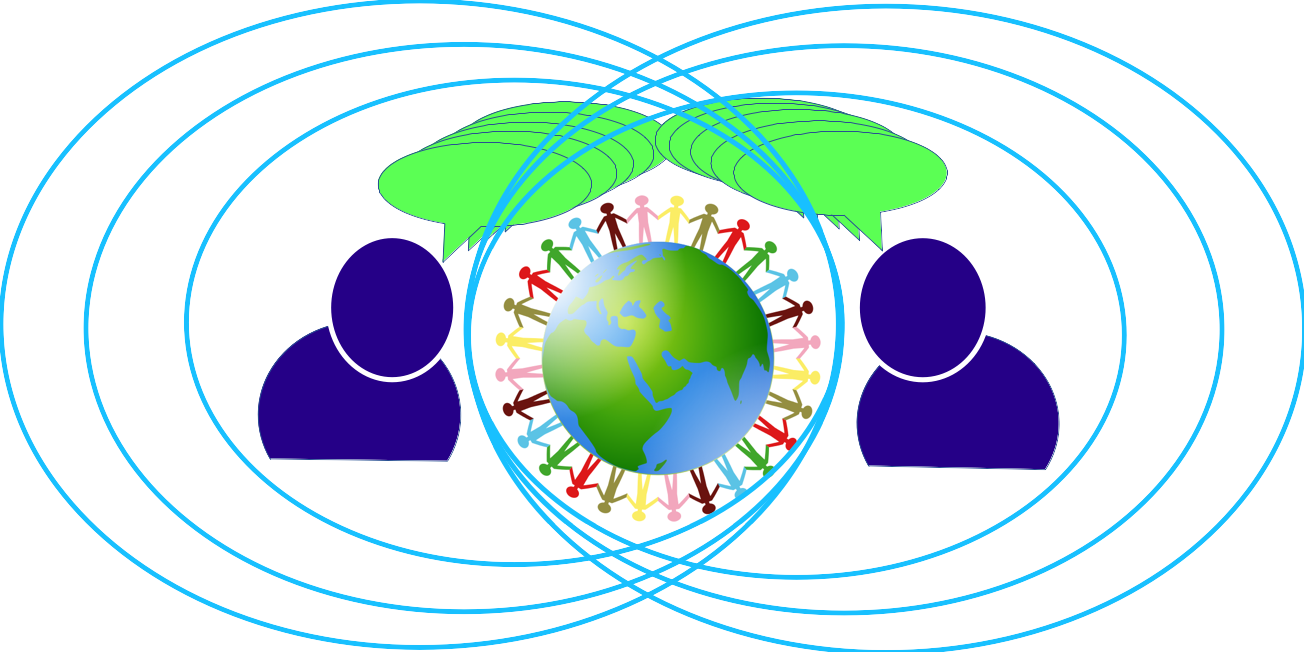

In the Introduction we provided a summary of the evolution of thinking related to the role of relationships in the counselling process. We positioned our approach to foregrounding the client–counsellor relationship in way that takes into account the cultural and systemic influences on both client and counsellor, as represented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Contextualized, Relational, Growth-Fostering Communication

We expressed the intent to examine critically the ways in which the relational practices of the counsellor and the nature of the therapeutic relationship may need to shift, adapt, or be altered in response to the specific cultural identities, contexts, values, worldviews, and needs of each individual client. In this section, we start by considering the person of the counsellor as an active contributor to the relationship, who brings with them both personal and professional experiences, values, worldviews, assumptions, and contexts that influence the therapeutic process. Then we invite you to enact an ethic of care as a foundation for optimizing the therapeutic and growth-fostering nature of the therapeutic relationship, as you bring yourselves as persons and professionals into the counselling process.

A. Person of Counsellor

It is not uncommon to hear someone refer to the counsellor themselves as one of the most important tools that can be brought into the therapeutic process. However, it is important to think critically about what that actually means. Is being a good person, a positive role model, someone who has also suffered and overcome life challenges, an effective communicator, a listening ear, and so on sufficient to ensure your effectiveness as a counsellor?

1. Counsellor Factors

In Chapter 1 we provided a broad overview of the common factors literature (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015; Norcross & Lambert, 2018; Nuttgens et al., 2021) and the literature on responsive relationships (Norcross & Wampold, 2018). In this chapter we draw attention to the counsellor factors that are recognized as influential in both client satisfaction with counselling and the outcomes clients experience.

Some common themes have emerged in the research on counsellor factors, including intentional foregrounding of client strengths, agency, and resiliency; the amount of counselling experience of the counsellor; and the ability of the counsellor to support development of a strong client–counsellor relationship (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015). More recent research on evidence-based relationship factors (Parrow et al., 2019) and evidence-based relationships and responsiveness (Norcross & Wampold, 2018) also highlighted counsellor authenticity, congruence, and genuineness as well as unconditional positive regard for clients, which are all factors commonly associated with counsellor ways of being (Rogers, 2007).

When we speak of counsellor factors throughout this chapter, including particular ways of being, we make the argument that these can only be fully understood and applied in the context of relationship. Returning to our questions above about the therapist as a counselling tool, we argue that it is the purposeful being and doing of the therapist, in-the-moment, in response to a particular client, and in the context of a growth-fostering relationship that optimizes therapeutic outcomes.

This relational context is reinforced by the emergent evidence on the influence on therapeutic outcomes of a real relationship between counsellor and client (Gelso et al., 2018; Norcross & Wampold, 2018). Gelso et al. (2018) defined this real relationship as “the personal relationship between [client] and therapist marked by the extent to which each is genuine with the other and perceives/experiences the other in ways that are realistic” (p. 434). We invite you to consider how you might contribute to a real relationship with clients and purposefully optimize counsellor factors by first positioning the client–counsellor relationship within an ethic of care.

B. Enacting an Ethic of Care

One of the ways in which counsellors can optimize their influence on counselling outcomes is by enacting an ethic of care from the moment they encounter each client. We are deliberately using the term, ethic of care, because the concept of care in the context of counselling must necessarily be considered within a framework of ethics. The important ethical question is: How do we ensure that our approach to caring is always in service of the client? Responsible caring is one the four key ethical principles in the CPA (2017) code of ethics: “Responsible caring requires competence, maximization of benefit, and minimization of harm, and should be carried out only in ways that respect the dignity of persons and peoples” (p. 4). The concept of an ethic of care, grounded in relational thinking and practice, dates back to the work of Carol Gilligan (1982) and was further developed though feminist and multicultural writings over the next few decades (Brown 2010; Jordan, 1997, 2010; Noddings, 2003).

Consider the interaction in the animated video below from the perspective of relationship-based, responsive caring. Where does the young person go awry in their attempts at care? What might they learn from this experience about the nature of relationship-based caring?

© Sandra Collins (2020, November 24)

An audio description of the video is provided is also provided below.

An ethic of care can be applied to relational practices in counselling to answer the question: What is helpful, from the client’s perspective, as I engage with this particular client, facing these specific contextualized challenges, and taking into account their preferences, cultural identities, social location, values, and worldview? (Collins, 2018b; Paré, 2013). This sounds simple enough, but we will spend a good portion of this ebook deconstructing what this looks like in actual practice and supporting you to become proficient in a care-filled approach to the counsellor–client relationship. The ethic of care forms the foundation for responsiveness in relationships and grounds the microskills and techniques we introduce, starting in this chapter, in the context of a values-based practice.

I remember first starting out as a counsellor during my master’s practicum with a great desire to be helpful and a clear sense of being unqualified to do so. I was asked to work with a woman around my age who had come to the agency for counselling on and off for a number of years. She was deeply depressed and struggled daily to find meaning in her life and the will to keep going. I had so much compassion for her, but I felt out of my depth in terms of my ability to help her. In consultation with my supervisor, I learned that she had been this client’s therapist for years, and I was strongly encouraged to keep working with her without great expectations for change. [I’ll set aside the ethics of this situation for now.]

I continued to meet with this client for a month or so, until I showed up at work one day and the police were already there. I knew immediately what had happened. They had come to deliver a letter that had been left in her home for me when she took her own life. I can still feel the anguish and grief that emerged in that moment, followed immediately by fear about what would happen next. I was given time alone to read her letter, and its content changed my view of counselling from that point forward.

In the letter, she explained that she had already made up her mind to take her own life before she came back to therapy. She didn’t know that she would end up seeing a new counsellor; she thought she would be coming in only once to enact a silent goodbye with my supervisor. However once we started talking, she realized that she needed someone to hear her and really see her before she left. She was not going to change her mind. She wasn’t looking for help to turn her life around. However, she realized that she did want to tell her story. She wanted to believe that someone would understand the choice she was making and not judge her for it. And, in the note she left behind, she thanked me for my “help” and “care” in these final moments of her life.

I did see her. I did care. She gifted me with her story, and I learned lessons I never forgot about client-centred caring.

Sandra

Reflections on an ethic of care

Consider the following questions for reflections on the ethic of care:

- What do you think it really means to be helpful on the client’s terms (Paré, 2013)?

- How might holding the perspective of client-centred care alter your approach to counselling?

- What helping or caring patterns have you developed in your life?

- How might these patterns influence, in helpful or unhelpful ways, your ability to engage in client-centred care?

1. Hospitality

Hospitality is not a word that we associate often with counselling practice. However, when you think about creating, and inviting clients into, a space that reflects an ethic of care, then the ways in which counsellors function as hosts for their clients becomes important.

Hospitality as evidence of an ethic of care

Think of a time when you tried to have an in-depth conversation with someone while you were physically uncomfortable, or when you walked into someone’s space (home or office) and immediately felt out-of-place. Then consider the video below in the context of the emphasis in Chapter 1 on welcoming clients and the focus in this section on communicating an ethic of care.

© Sandra Collins (2020, November 24)

An audio description of the video is provided is also provided below.

As we prepared to write this section, we shared stories of our own encounters with therapists and stories from our friends or colleagues. The lack of sense of hospitality was actually quite shocking: eating lunch in front of the client, doing their nails during the session, falling asleep, taking a puppy out to pee, checking text messages, going to the staff room to refill coffee, talking only about themselves, asking the client to get out of the therapist’s preferred chair. The fact that we could generate this list in a few minutes suggests that barriers to hospitality are not uncommon. Take a few moments to reflect on how you might communicate an ethic of care through the relational practice of hospitality.

Learning to be a host

One of the ways that I have evoked hospitality is by making tea for my clients. I note in the first session the type of tea each client prefers, and I have a pot of the client’s preferred tea, and sometimes their preferred teacup, ready when they arrive. Among other things, this communicates that I have thought about them in advance and created a space specifically for them. I invite you to make yourself a cup of tea (or other preferred beverage) as you sit down to complete the rest of the learning activities in this chapter and to consider how acts of hospitality can alter your sense of feeling welcome.

If you have never been for therapy yourself, now might a good time to start, not because of the therapist-heal-thyself mandate (although this is also a valid reason), but because it is important to experience what it is like to spend an hour with another human being and to talk openly about issues you may never before have shared! The experience will help you to understand more deeply what is being asked of you as a counsellor. My only caution is to choose your counsellor wisely, perhaps by referral.

I have seen a number of counsellors over the years for a variety of reasons. I consider it a gift to myself. The tea ritual was modelled by a therapist I worked with during my graduate studies. Currently, I schedule an appointment a few times a year just to talk about my life, consider new possibilities, have a sounding board for things I am working through, or just to reflect and be attentive to my evolution as a person. This practice of receiving empathy and compassion builds my own capacity for offering this ethic of care to others.

Sandra

Hospitality may be easier to envision in a face-to-face environment; however, teletherapy and videotherapy is an important alternative in pandemic and post-pandemic times. As counsellors develop the learning and tools to use technology in counselling, they will be better able to serve the needs of clients who cannot leave their homes, but who need access to therapy (Sutherland, 2020). Therefore, it is important to be purposeful in creating a welcoming environment for clients in video and phone counselling spaces. Therapists can successfully communicate at an emotional level and foster a sense of hospitality (Benoit & Kramer, 2020; Sutherland, 2020) through technology-mediated conversations. Consider the following tips:

- Find ways to invite clients into a predictable, welcoming space by not appearing on video from different parts of your home, attending to lighting, reducing clutter, and choosing backgrounds that are warm, but not distracting.

- Offer some alternative visual stimuli, so clients don’t feel they need to look directly at you all of the time (e.g., a neutral photo or painting, a window that ensures privacy), but avoid a background made up of degrees and awards.

- Place your computer at eye level to provide a sense of conversing directly with the person in front of you that is similar to an in-person conversation, but sit back a bit from the screen so you do not appear as a disembodied head.

- Attend to nonverbal communication (e.g., tone of voice, warm smiles, welcoming posture).

- Take extra time to build rapport, focusing on who they are as people, before asking questions about why they have come to counselling.

- Share a bit about your own environment to increase their sense of safety and privacy.

2. Trust

Both hospitality and the expression of compassion can form a foundation for building trust between counsellor and client. From the client perspective, trust “involves feeling confident or assured that the counsellor is reliable, authentic, and capable of supporting progress towards their preferred outcomes” (Collins, 2018b, p. 1034). In this sense trust is intimately connected to counsellor credibility; however, trust is earned through relationship, not simply through credentialing. With some clients, the foundation for trust or distrust may be primarily interpersonal (Jordan, 2010; Lenz, 2016). Certain relational practices addressed in this ebook are designed to support the development of interpersonal trust (e.g., rapport building, sharing power, and communication of empathy).

However, trust and mistrust may also be intercultural and historical (Collins, 2018b; Dupuis-Rossi, 2018; 2020). The ongoing cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples through colonization, enacted at community, organizational, economic, and political levels (Dupuis-Rossi, 2018; 2020; Fellner et al., 2016), as well as the specific experience of systemic racism in encounters with healthcare practitioners, results in justifiable and sensible mistrust on the part of some Indigenous clients. The continued cultural oppression of other nondominant populations (e.g., 2SLGBTQIA+ persons, individuals from working or poor social classes) (Lavell, 2018; Nyland & Temple, 2018) also results in barriers to trust in healthcare systems and practitioners. Building or rebuilding trust in this case may be supported by other relational practices (e.g., building cultural safety, trauma-informed practice).

Trust is a gift clients offer, often based on their assessment of the person of the counsellor more than the credentials displayed on the wall. As counsellors we do not deserve to be trusted based on our position or education, we must actively earn each client’s trust through our care-filled and client-centred ways of being and ways of relating.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

One of the main themes in both Paré (2013) and Collins (2018a) is that counselling relationships are intentional practices. The counsellor’s way of being in relationship should reflect a deliberate, purposeful way of engaging with clients. Paré (2013) argued that viewing relationship as a practice requires us to shift “attention from a preoccupation with being our true selves to asking how the client is being affected by any particular version of self that we bring forward” (p. 82). Pause for a moment, and list the people in your life who know absolutely everything about you and see all of you in each moment of your time together. Our guess is that there are very few people, if any, that you would add to this list. Even in our most intimate relationships, we lean into parts of ourselves moment-by-moment that best serve that relationship. This is not the same as losing yourself. Rather it is about (a) attending to the relationship, because it is important to you and enhances your life and (b) responding to what you know about the other person’s needs, communication style, and ways of relating. As we move into talking about the how to of counselling in this section, it is important to hold this lens of intentionality and responsivity in foreground. This applies even as we talk about counsellor characteristics that you may initially assume are inherent to who you are as a person and a professional.

A. Ways of Being

One of your first tasks in counselling is to build a care-filled connection with each client, most often referred to in the counselling literature as establishing a sense of rapport. The Merriam-Webster (n.d.) dictionary defines rapport as “a relationship characterized by agreement, mutual understanding, or empathy that makes communication possible.” Building and maintaining rapport with clients is an ongoing process. Counsellors should not assume that rapport will happen naturally; rather they must actively attend to the factors that facilitate rapport with each individual client. It is the counsellor’s responsibility to ensure that these foundational conditions for building a therapeutic relationship and communicating effectively are created and maintained. We begin below by considering how counsellor ways of being influence the development of rapport and the creation of care-filled connection with clients.

Carl Rogers (2007) asserted that the key to constructive therapeutic work is the relational atmosphere established by the counsellor, which is commonly referred to as the counsellor’s ways of being. It is important to note that Rogers posited these core conditions that support client growth and healing as “characteristics of the relationship” (A Relationship section, para. 2) rather than qualities inherent to the practitioner. Brown (2007), speaking from a feminist therapy perspective, stated: “Most psychotherapists in my experience would prefer to feel as if they are doing something, rather than being with someone” (p. 257). We argue that the functions of being and doing are, in fact, complementary if counselling is positioned as a relational practice, because this framework adds the important layer of intentionality to both a counsellor’s being and their doing (Collins, 2018a; Paré, 2013).

It is our position that neither doing nor being are sufficient in and of themselves; however together, purposeful and responsive doing and being can result in ethical, care-filled, and culturally responsive practice (Collins, 2018a). Let’s start by considering what is meant by being on the part of the counsellor.

Being from a place of wholeness

Contributed by Melissa Jay and Amy Rubin

Melissa and Amy share a passion for working with counsellors to bring themselves into the counselling relationship from a place of wholeness, as integrated human beings. In this short video, they talk about their own experiences of working from this place of whole being with their clients.

© Melissa Jay & Amy Rubin (2021, February 19)

Take a moment to breathe, and reflect on your understanding of wholeness of being. How might personality, cultural identities and social location, theoretical leanings, lived experiences, and other factors influence both your response to, and your preparedness for, being with clients from a place of wholeness.

1. Authenticity, Genuineness, and Congruence

As we move into talking about building rapport with clients in this section, we begin by considering specific ways of being that have been identified as central to evidence-based, responsive relationships (Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Parrow et al., 2019). Rogers (1961, 2007) positioned authenticity, genuineness, and congruence as relational constructs that play out in the moment-by-moment interaction with the client. Paré (2013) reinforces this idea of relational context by arguing that authenticity must be understood in the context of what is helpful to this particular client in this particular therapeutic moment. Reflect again on the video by Melissa and Amy. How might you distinguish between bringing yourself in wholeness into your relationships with clients versus bringing your whole self into each moment of relating? Paré speaks to this distinction by contrasting the idea (myth) of the counsellor’s (or anyone’s) true self with a more intentional application of responsive versions of self.

From a social constructivist perspective, the person of the counsellor and the person of the client are both co-constructed, to some degree, within the context of the relationship. Consider the responsive relationship between the octopus below and its environment.

© Dmitry Salnikov (2017, February 4)

Identify two people in your life whom you value and with whom you are comfortable, but whom you perceive as significantly different in personality from each other (or as far apart as you can get). Reflect on your last encounter with each of these people. How did you greet them? How did you interacted with them? What did you share about yourself? What do you think they valued in your interaction with them? What do these reflections tell you about the version of yourself that you brought to these encounters. How did you express your authentic self differently to each person?

Counsellor wholeness is connected intimately to the experience and expression of congruence. Congruence involves counsellor self-awareness of their thoughts and feelings in-the-moment as well as manifestations of those internal states to clients (Parrow et al., 2019; Rogers, 1961, 1970). Congruence is expressed through some of the specific microskills addressed in this chapter (e.g., body language and other nonverbal forms of communication) as well as through microskills in later chapters (e.g., self-disclosure, immediacy).

2. Openness and Honesty

Rogers (1961, 1970) is also credited with humanistic psychology’s focus on openness and honesty on the part of the counsellor. Openness and honesty are meaningful companions to genuineness, congruence, and authenticity, and support the counsellor’s communication of these ways of being to the client. Feminist therapists also emphasize demystifying the counselling process from the first encounters with clients and being open and transparent moment-by-moment throughout the counselling process (Brown, 2010; Worell & Remer, 2003). The microskill of transparency is introduced in this chapter and reinforced in Chapter 3 when we discuss the process of articulating the limits of confidentiality to clients and engaging their informed consent (Brown, 2010; Chew, 2018).

Openness and honesty about the counselling process is particularly important with clients from other cultures who may be unfamiliar with the practices and conventions of counselling (Bemak & Chung, 2017). These qualities are foundational to many of the relational practices that we will address later in the ebook (e.g., cultural safety, power-sharing, trauma-informed practice, mutual cultural empathy).

Where does openness and transparency start and end: The mystery of note-taking

Note-taking is an important process in documenting the counselling process for clients, for therapists, and for the organizations in which they are embedded. Most often, counsellors follow the lead of counsellor educators or supervisors as they establish note-taking processes and styles. In this video, Sandra Collins invites you to step back and consider the process of note-taking from the perspective of a values-based way of being with clients.

© Sandra Collins (2020, December 2)

Position yourself as the client in counselling, and reflect on what you would what to know about the notes written about you.

- How might your personal experiences of colonization, systemic racism, or other forms of cultural oppression leave you justifiably distrustful of records being kept about you within health systems?

- How might you make your note-taking process more transparent to clients?

3. Unconditional Positive Regard and Nonjudgement

Rogers (2007) defined unconditional positive regard as “a warm acceptance of each aspect of the client’s experience as being part of that client. . . . It means that there are no conditions of acceptance, no feeling of ‘I like you only if you are thus and so’” (p. 243, italics in original). Clients often come to counselling with low self-esteem, disappointment in themselves over choices they have made, internalized homophobia or other forms of cultural oppression, or a sense of disempowerment. Unconditional positive regard has emerged through the evidence-based responsive relationships research as an important factor in client outcomes (Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Parrow et al., 2019). This goes beyond acceptance of client perspectives to deep appreciation for them as cultural beings who have an inherent right to self and group identity, autonomy and self-determination, and full participation in society.

Unconditional positive regard and nonjudgement: Choosing language that builds connection

Contributed by Ivana Djuraskovic

In reflecting on unconditional positive regard and nonjudgement, Ivana points to the ways in which language can empower or disempower those with whom we engage. She challenges the ways in which language is sometimes used to characterize a person, rather than to describe the challenges with which they struggle.

© Ivana Djuraskovic (2021, April 25)

Reflections:

- How does your understanding of unconditional positive regard fit, or not fit, with Ivana’s perspective?

- Ivana points out that that we all hold judgements, the issue is what we do with those judgements. How might you acknowledge the judgements you hold, while simultaneously opening up space for conversation and healing?

- How do you understand the relationship between nonjudgement and compassion? What is their connection to listening openly and fully to client stories?

We position unconditional positive regard and nonjudgement as aspirational: No counsellor will ever be able to be completely free of judgement. Parrow et al. (2019) emphasized the relational nature of unconditional positive regard and nonjudgement, noting that it is important for counsellors to discern how best to express these to each client. They advise against overt statements such as, “I value you as a person,” in favour of specific microskills and relational practices that communicate respect and nonjudgement. In this chapter we will start with the basics of listening and attending actively, embracing silence, and paraphrasing as ways of creating space and communicating to clients that their thoughts and feelings are valued and that they are being heard. Couching these responses within an ethic of care keeps the focus on client-centred responsivity. The skills of validating (Chapter 3) and offering affirmations (Chapter 4) provide more direct opportunities to communicate unconditional positive regard and nonjudgement.

4. Curiosity and Not-knowing

Unconditional positive regard and nonjudgement are supported through a stance of curiosity. In the context of counselling, curiosity goes beyond interest in client lived experiences to holding a space for discovery of the unexpected. It involves setting aside preconceptions that may come from the counsellor’s cultural worldview, lived experiences, theoretical orientation, or clinical practice. Paré (2013) defined not-knowing as a “deliberate suspension of preunderstandings . . . in the service of the client” (p. 428). These concepts are also rooted in constructivist perspectives on the relational natures of knowing and knowledge-building, through which we position shared understanding between counsellor and client as continuously co-constructed through interactions with each other (Bava et al., 2018).

Judicious expressions of curiosity on the part of the counsellor support the initial and ongoing development of the client–counsellor relationship (Willis-O’Connor et al., 2016). These ways of being will form a foundation for many of the microskills and techniques we use to model multidimensional inquiry into client lived experiences throughout this ebook. One of the core messages of this chapter is: Slow down and listen. Jumping to the assumption that you have “got it” may actually make it more difficult to remain open to the uniqueness of each client you encounter.

Assuming a not-knowing stance

Take the opportunity over the next couple of days, in an encounter with a family member, friend, or colleague, to approach your conversation with them with curiosity in the forefront of your mind. Focus on what they are telling you, and invite more detail. Ask questions that communicate your interest in their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Assume that you don’t understand their perspectives or the meaning they attach to their experiences, and pursue greater understanding from this not-knowing position. Next, reflect on what you learned about them through this encounter that you might not otherwise have known.

One of the most challenging things for new counsellors is to slow down and simply listen; they sometimes feel an urgency to “do” something rather than attending to the client need for them to “be” something. This may lead to premature foreclosure on conversations in which important details of client values, beliefs, worldviews, and lived experiences can be overlooked. How might you apply the principle of curiosity and not-knowing within each encounter with your clients?

From Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by Collins, 2022, Counselling Concepts (https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc11/#assumingnotknowing). CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

We will pause frequently in this ebook to query the cultural roots and responsivity of various concepts and principles that are often taken for granted in the professional literature. Ways of being is one of those concepts. Many of the concepts related to counsellor ways of being emerged from eurowestern psychology and may not be inclusive of, or responsive to, the core principles associated with health and healing in other cultures. We have intentionally centred diverse voices in this resource to encourage critical reflection on what each client might consider welcoming, responsive, care-filled relational practices on the part of the counsellor. As noted in Chapter 1, one of the core principles of responsive relationships is that even evidence-based relational practices may need to be adapted or applied differently based on client cultural contexts. Cultural curiosity adds another layer of not-knowing, which involves openness and inquisitiveness about the client’s cultural identities, values, worldviews, and contexts (Mikhaylov, 2016). However, it is important to remember that the foci of cultural curiosity and not-knowing extend beyond the content the client shares about their lived experiences to the processes of counselling, including the ways in which clients’ experience relationship.

Reflections on ways of being

- What is the relationship between who you are and what you do?

- In what specific ways are who you are and what you do a reflection of your cultural identities and social location?

- How does the client’s cultural identity and social location influence the appropriateness and efficacy of your ways of being as counsellor?

- To what degree can ways of being be shaped through practice, feedback, and self-reflection?

- In what ways are counselling relationships a process rather than a thing?

- How does positioning the client–counsellor relationship as a process shift the ways in which you might attend to it differently with each client?

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

To support your learning process, we have created the Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary, which outlines all of the microskills and techniques that we will introduce throughout the ebook. A techniques summary will be added in a later chapter. As we introduce each one, we will copy rows from the document into the chapter. You will want to look periodically at this summary document to position these skills in context. In this chapter, we focus on microskills that we see as particularly relevant for communicating care and building rapport with clients.

A. Responsive Microskills

Recall from Chapter 1 that we define microskills as particular forms of questions or statements that serve a specific function within the counsellor–client dialogue. They are typically single sentences with a particular structure and purpose.

1. Engaging Through Body Language

Some of you may be familiar with the acronym SOLER (Egan, 2002), which is commonly presented in conversations about body language in counselling: Sit squarely, Open posture, Lean forward, Eye contact, and Relaxed. This seems like a relatively simply reminder as you position yourself, literally and figurative, to engage with clients. The problem is that these instructions are devoid of the client, and responsive counselling relationships cannot be reduced to such simple universal principles. Take, for example, the suggestion to maintain eye contact with clients. In many eurowestern cultures, direct eye contact is associated with attentiveness. However, in many Arabic and Asian cultures direct and sustained eye contact between men and women is considered inappropriate. In other cultures sustained eye contract is viewed as confrontational, whereas respect, particularly for elders or those in authority, is communicated through avoiding eye contact. Cultural differences also exist for other nonverbal communication through body language (e.g., greeting norms, physical contact, hand or head gestures, posture).

The following table provides some basic guidelines for responsive and client-centred body engagement through body language. We have drawn the table from the Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| N/A |

|

|

|

Leaning into global hospitality

Over the course of your career as you shift the contexts of your practice, you will hopefully encounter clients (as well as colleagues) from all over the world. In our teaching and practice, this is a treasured pleasure and privilege. For this activity, you are invited to think ahead to the ethnicity of clients you are likely to encounter in your own community, particularly those with whom you are less familiar. Choose at least three ethnic communities and search for information about cultural norms to complete the table below. Pay careful attention to the intersections of other dimensions of cultural identity (e.g., age, gender, social class, religion). PDF version.

| Cultural Norms | Cultural Community 1 | Cultural Community 2 | Cultural Community 3 |

| Eye contact | |||

| Greeting norms | |||

| Physical contact | |||

| Hand gestures | |||

| Head gestures | |||

| Posture | |||

| Other |

Reflect on your own cultural norms in relation to those you discovered. Write a list of tips for yourself to ensure that you think critically about how you engage through body language. Consider carefully how just “doing what comes naturally” in your encounters with clients may not reflect or communicate an ethic of care.

Rapport building through nonverbals and body language with children: An art therapy focus

Contributed by Lisa Thompson

Age differences can also introduce challenges to effective communication, both verbal and nonverbal. For those of you who plan to work with children or families, it is important to consider how you might adjust your nonverbal communication to create an invitational space for children. In this video Lisa describes how she approaches art therapy practice with children, with careful attention to body language and other nonverbal forms of communication.

© Lisa Thompson & Gina Ko (2021, March 21)

Take a moment to sit on the floor (if you are able to do so), and imagine what it would be like to approached by an adult you don’t know, especially an adult whom you perceive as having some kind of authority or power. Breathe and attend to your emotions and body sensations as you picture their approach. What might you take away from this perspective to enhance your nonverbal communication with children?

2. Listening and Attending Actively

Think of a time when you’ve felt profoundly listened to. This may have been one instance, or perhaps many conversations with a particular individual. Then reflect on the following:

- the actions of the listener that communicate listening,

- adjectives that describe that quality of listening,

- your cognitive and affective (embodied) experience of being listened to, and

- the implications for developing an effective client–counsellor relationship.

Next, reflect on a time when you have not felt heard, and reconsider the prompts above, replacing listening with not listening. What can you carry forward from these conversations to enhance your ability to listen attentively and actively?

To listen and attend actively, counsellors must value and respect both the telling of stories and the storyteller. We invite you to approach each encounter with the curiosity and nonjudgement discussed above to make room to appreciate what is being shared with you. In Chapter 1 we talked about preparing the physical and virtual space to eliminate barriers or distractions and to create mental and emotional space for therapeutic conversations. In this chapter we focus on preparing the person of the counsellor, so that you are able to listen openly and respond effectively. Particularly early in your professional development, there may be emotions, stories, or lived experiences that you find difficult to hear. Developing your skills as a listener will complement your intentional ways of being with clients and support you to stay present and available to them.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| N/A |

|

|

|

Listening is such a foundational communication skill that people often take for granted their competency in this area. However, active listening in the context of counselling requires three processes, and there are challenges and risks for communication breakdown in each.

- Receiving the message from your client. As we continue to focus on the person of the counsellor in this chapter, it is important to recognize both the strengths you bring to the counselling process and the ways in which you can, potentially, stand in the way of effective communication. Everyone has filters through which they process information. These filters can be idiosyncratic, stem from early learning in relationships, or derive from cultural identities or social locations, and sometimes they are a reflection of social discourses grounded in cultural discrimination or other biases. These filters function like earmuffs in the counselling process, distorting or blocking out part or whole messages from the client.

- Processing the message you received. When portions of the client’s story are muffled in this way, the counsellor may tend to fill in the blanks with information from their own experiences, values, worldview, or cultural expectations. In this case, they are no longer reflecting on the message the client intended to send, but rather on the message they have reconstructed. Most often this is completely unintentional and, to a large degree, natural. However, it behooves counsellors to bring into conscious awareness the various filters that can lead to message distortion in client–counsellor interactions through self-reflection, communication skills practice, and feedback.

- Responding to the message you received. The third element of listening is sending a message back to the client that they have been heard. In this chapter we focus on two simple counselling microskills that communicate active listening and engagement to clients (i.e., minimal encouragers and paraphrasing). These responses to the client provide a preliminary opportunity to receive feedback on your listening skills as you attend to their nonverbal and verbal responses. In later chapters we introduce other microskills that are designed to invite clients more fully into your processing of their messages with a view to ensuring you are on track and to co-constructing a shared understanding of their lived experiences (i.e., reflecting feeling, reflecting meaning, summarizing).

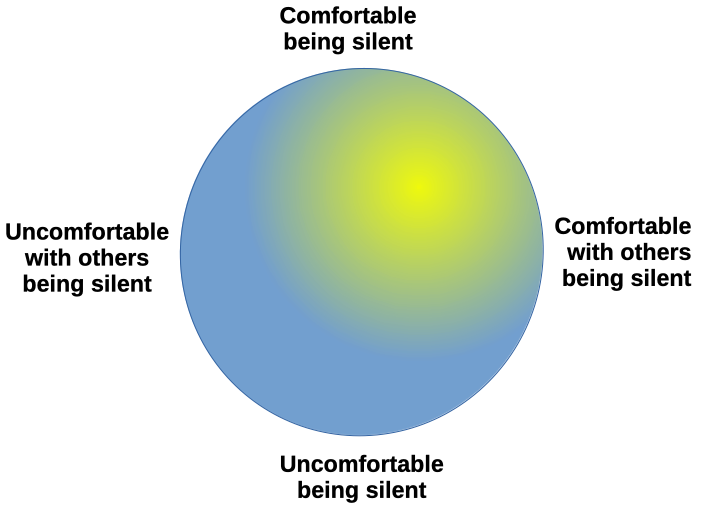

3. Embracing Silence

Comfort with silence is an essential skill to hone. In some counselling contexts, there are moments when the most appropriate response from the counsellor is silence: a moment of listening and waiting and being present with the client while the client processes their current experience. However, it is also important to follow the lead of the client to ensure that they are not uncomfortable with the silence. A comfortable pause allows both counsellor and client to gather their thoughts or process their feelings. This is different from the counsellor being inactive or scrambling for a response (and thus silent).

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

|

When I was in grad school, I remember being very intimidated by the prospect of recording my counselling practice sessions. However over time, I found this experience to be immensely helpful. At one point we were asked to review a series of our sessions without the sound, so that we could critique our nonverbal behaviour. I noticed that often when I sat with my legs crossed, the moments of silence were filled with a rapid back-and-forth movement of one foot. My anxiety about not knowing what to say next was completely transparent through my body language, as my mind worked overtime. I was not creating a comfortable, relaxed pause for myself or for the client, who could not help but to watch my foot tick away like a metronome.

Later during my doctoral practicum, I worked with a client who did not speak for the first five sessions. Literally, she did not utter a single word or engage in any direct way. She arrived on time, she sat down for the hour, she appeared to be listening some of the time, but there was no reciprocation, verbal or nonverbal. For me this was a tremendous challenge and an incredible learning opportunity. I worked hard at first to engage her and invite a response. And then I decided simply to be with her. I talked a little bit over those first five weeks about the counselling process, I did a few grounding exercises out loud so she could participate or not, and I sat silently most of the time. In the sixth session, she started to talk, tentatively and intermittently. I discovered that her degree of dissociation was so extreme that she rarely knew what mode of transportation she had used to get to my office, yet she came for those five weeks faithfully until she was able to bring herself into the room and to trust me enough to stay present for longer and longer periods of time.

Sandra

Silence as a relational practice

How comfortable are you with silence? Position yourself on the following image based on how comfortable you feel when others are silent for extended periods of time and when you are expected to be silent for extended periods of time.

If you positioned yourself in the cooler (blue) areas of the circle, consider finding a family member or friend with whom to practice silence. Choose someone who is more comfortable than you with silence. Ask that person to sit in silence with you, observing your body language. Practice communicating engagement through silence. Invite feedback, and try again. We refer often to relational practices in this ebook, because these skills do take practice.

If you positioned yourself in the cooler (blue) areas of the circle, consider finding a family member or friend with whom to practice silence. Choose someone who is more comfortable than you with silence. Ask that person to sit in silence with you, observing your body language. Practice communicating engagement through silence. Invite feedback, and try again. We refer often to relational practices in this ebook, because these skills do take practice.

4. Offering Minimal Encouragers

Interjecting minimal encouragers into a conversation is one of the ways to communicate listening and engagement as well as to invite clients to continue to share their stories. Skillful use of minimal encouragers flows seamlessly in a conversation. Overuse of minimal encouragers can suggest that you are struggling to attend, you cannot think of anything else to say, or you want the client to speed up the telling of their story.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| N/A |

|

|

|

Nonverbal Attending: Listening and attending actively, minimal encouragers, and silence

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In the video below Gina encourages Sandra to open up about her current challenge by paying particular attention to listening and attending actively, using minimal encouragers, and optimizing the use of silence. Notice how Gina uses these microskills to demonstrate an ethic of care and to build rapport with Sandra.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 1)

Sandra continues to share her experiences, in part, because of the welcoming space that Gina creates through her visible engagement and presence with Sandra. Gina’s silence is comfortable for Sandra; however, other clients may require more verbal encouragement at this point in the counselling relationship. It is important to attend to nonverbal clues to client comfort.

5. Paraphrasing

We are deliberately including paraphrases as part of listening, attending, and building rapport early in the client–counsellor relationship. Our rationale is that by effectively restating or rephrasing the client’s words, counsellors are able to let them know they are listening. What distinguishes paraphrasing from reflecting feeling (Chapter 5) and reflecting meaning (Chapter 6) is that a paraphrase does not add inferences about client thoughts or feelings; rather it mirrors back to the client what they have said in the same or similar words. For example, the client may state: “I have been so busy with work that I haven’t had time to think about my relationship with my children.” If you replied, “Work is really busy” or “You have spent your time on work,” you have not added any new information, and this would be classified as a paraphrase. However, if you said, “Your priority seems to be work,” you have made an inference about the meaning of the client’s statement (i.e., what they prioritize), thus making your statement an example of reflecting meaning, which we address in Chapter 6.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

Client: It’s been a long time since I felt confident enough to put myself out there.

|

Effective and ineffective paraphrasing

Animated video

The following video demonstrates the use of paraphrasing to communicate engagement with the client’s story. Notice that each of the counsellor statements draws on the client’s own words or rephrases their words slightly.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 6)

The purpose of a paraphrase is to communicate to the client that you are listening attentively and that you are picking up on important elements of the messages that they are sending. This is not the same as simply parroting what you have heard. There are occasions when restating what a client has said can be effective; however, repeated or nonresponsive use of restating can easily derail the conversation.

Paraphrasing: Sticking close to what the client has said

Featuring Sandra Collins and Gina Ko

In the video below, Sandra focuses on paraphrasing what Gina is saying about her driving challenges. Notice how Sandra sticks close to the language that Gina uses, even though she is not simply restating Gina’s exact words.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, February 9)

Sandra does not add meaning or make inferences about Gina’s feelings. The goal is simply to communicate that she is listening attentively to what the client is saying.

6. Providing Transparency

One of the primary purposes of transparency is to remove the sense of mystery that often accompanies the counselling process (Turns et al., 2019). Transparency tends to be a frequently used microskill in the early part of the client–counsellor relationship as you establish a foundation for working together. For many clients, counselling is a completely new experience, and they don’t know what to expect. Other times they may have misperceptions about counselling based on popular media or previous experiences with healthcare practitioners that can be important to dispel.

| Structure | Description | Purpose | Examples |

| Statement |

|

|

|

Providing transparency

Animated video

In the video below, we pick up the story of Lulu, introduced above. Jason, their counsellor, uses the skill of transparency to provide them with information about group counselling as a supplement to the individual work they are doing together.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 6)

Consider the kind of information that clients might want to access about counselling generally or your approach to the counselling process specifically. How might you be proactive in providing this information to help dispel any a potential sense of mystery about the therapeutic process?

Please note the intentional use of the singular they, them, and their and other gender-neutral language throughout this ebook. There are multiple expressions of gender in society, and there is more recognition in the 7th edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020) of appropriate language to capture that cultural reality (see pages 120–121). Check out the Singular “They” (APA, 2019) for more information. We use the pronouns he and she only in reference to specific individuals whose chosen pronouns are known to us or in a purposeful way in client scenarios. We also use the pronouns he and she if these pronouns have been introduced by the client(s) in videos contained in this resource. Often, these gender-specific pronouns apply when the client references another person in their lives.

Two other common uses of transparency are (a) providing an overview at the beginning of a session so that the client has a clear sense of the direction in which you are headed, or (b) providing a transition to change directions part way through a session. For example, you might start a session with an overview like, “Last week we were talking about . . . I’m wondering if it’s a good idea for us to start where we left off on this issue. I’m curious about whether your perspective has changed as you look back on that conversation.” Then after a few minutes you might introduce a transition such as, “Now that I have a better sense of where you are at on this issue, it might be helpful for us to shift gears a bit to talk about . . .”

Using transparency to create a meaningful structure for the counselling session

Animated video

We now continue the story of Lulu. In this segment Jason, their counsellor, uses the skill of transparency to provide an overview of a possible direction for the conversation. Later Jason uses transparency again as a transition to narrow their focus. Notice how each of these microskills help to provide some structure to the conversation.

© Sandra Collins (2021, April 6)

Jason provides transparency in a way that creates space for Lulu to agree or disagree with the directions he suggests by selecting tentative language and waiting for her response.

We have attempted to model the use of transparency to add meaningful structure to this ebook by creating the mind map to introduce you to the big picture of where we are headed, followed by focusing in-depth on one section of the mind map in each chapter. You will notice that we also start each chapter with an overview and use transitions to make clear the links between various topics and skills that we introduce. Think of examples that have been useful (or maybe not so useful) to you.

7. Skills Synthesis

In most chapters where new microskills are introduced, we will end the Microskills and Techniques section with one or more demonstration videos that pull together most or all of these communication skills. We hope that these videos will incrementally demonstrate the ways in which counselling microskills can be intentionally combined to accomplish particular relational practices and advance specific counselling processes. In this chapter, the focus has been on communicating care and building rapport.

Building care-filled connection

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

The video below demonstrates each of the microskills introduced in this chapter, combining body language, active listening, and silence with the use of minimal encouragers, paraphrasing, and transparency. You will notice that Gina uses a few microskills at the beginning of the video that we will introduce in Chapter 3. She then moves into demonstrating those focused on in in this chapter.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2021, February 2)

Take a moment to reflect on how these microskills support the counsellor to communicate engagement and to offer the client a sense of being heard, both within the context of an ethic of care.

Throughout this ebook, you will view and analyze a number of videos that were created by counselling practitioners and faculty at various universities. You will notice that, most often, they talk about real issues in their lives as they share their personal experiences and challenges in the role of client. Our intent is to model the type of skills practice that will optimize your development as a learner. Although these are not real counselling sessions, you are expected to treat the videos with respect and to use them for only the purposes intended in this resource.

If you choose to participate in the applied practice activities we include, we encourage you also to speak about real issues with your partner. It is much easier to practice your counselling skills if the person you are working with is providing genuine responses. You will also notice, however, that we do not delve into traumatic experiences or crises in our lives. For the purposes of practising your skills, you may want to draw a clear boundary at topics that evoke intense emotion or require you to reveal information that you would not be willing to include in other professional development or educational contexts. Although each individual will draw this boundary differently, please also consider the person in the role of counsellor when you select topics for skills practice.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

This chapter introduced counsellor factors that have the potential to influence counselling outcomes, along with some relational practices and counselling microskills to support building rapport with clients in the context of an ethic of care. As we move into reflective practice considerations in this section, we circle back to the person of the counsellor by highlighting the importance of self-awareness. Purposeful interactions with clients grounded in counsellor ways of being are possible only if the counsellor is committed to, and actively engaged in, continuous self-reflection.

1. Self-Awareness

For most counsellors, psychologists, counsellor educators, and supervisors, self-awareness is part of daily practice. This does not mean that self-awareness, at the level required for professional competency, comes naturally; rather, it is another form of relational practice (relationship to self) that is part of ongoing professional development (Pompeo & Levitt, 2014 ). Self-awareness involves intentional, honest, and critical reflection on the counsellor’s inner self (or the selves-in-context we talked about in this chapter) to consider thoughts, feelings, embodied experiences, values, beliefs, assumptions, biases, and so on (Ackerman, 2020). Coll et al. (2019) identified self-reflection and awareness as one of five types of defining moments in counselling practice that contribute substantively to personal and professional growth. As a novice counsellor, you may be more likely to notice critical self-talk, self-consciousness, and struggles to stay focused as you become more mindful and self-aware in-the-moment with clients (Pearson, 2020). However, self-awareness and self-awareness training have been found to be positively correlated with increased well-being at work, and self-aware individuals are more likely to exhibit increased appreciation for diversity, enhanced confidence, and improved communication skills (Sutton et al., 2015). We invite you into this important lifelong journey of becoming self-aware counsellors (Pompeo & Levitt, 2014 ).

Consider the reflection below from Gina about self-awareness. We will introduce the process of self-disclosure in Chapter 3 with further information about how to discern when and what to disclose.

When I am sitting with a client, listening to their emotions and lived experiences, I sometime notice that I am feeling more sad and angry. It is important for me to pause and to reflect on the meaning of my internal responses. For example, I worked with a Korean client, Kim (pseudonym), who was highly distressed and felt hopeless, because her husband had recently told her that he had another family in Asia. He was in the process of sponsoring them to come to Canada, and he hoped she would allow them to settle in the house she shared with her husband. She was devastated and shocked by this news. Their children told her to cut ties with him, and she was deeply heartbroken, overwhelmed, and critical of herself, because she still loved him.

In moments of sitting with this courageous client, who was willing to come talk to me despite the stigma of accessing counselling services (Chapter 1), I noticed that I ferociously sided with her. In my in-the-moment self-reflection, I recognized that my reaction was rooted in my own experience, because my father also had had another family in Asia. Years ago I found out that his other children were the ages of my children. He did not raise me and my siblings, and I have no emotional connection with him. He has since passed. However when my client shared her heartbreak, I returned to thinking about what he did to my family. He abandoned us when I was in elementary school. My mom became a single mom with three young children. As a result we had to move into government housing, and we lived under the poverty line for many years.

Without engaging in self-reflection and becoming aware of my internal state of high resonance and alignment with the client, I might have shared my story with her, thinking that my self-disclosure was about supporting her. However, I was able to observe my internal responses while keeping in mind that she might not have felt safe with me if she perceived me to be siding with her children. She may have asked what I thought about her children’s urge for her to end contact with him.

Part of me wanted to disclose my story, because I wanted her to know that I empathized with her similar experience. However I sensed that our therapeutic relationship and encounter might shift because of the differences in our stories. Coming from an Asian background, Kim might have wanted to learn more about my experience and may have asked for more directive advice on my part, and I thought it was important to balance directiveness and nondirectiveness in our therapeutic interactions.

In the end, I choose not to share my story with Kim, because I was aware that it could cause more confusion. I continued to use self-awareness to gauge how much I shared to ensure that any sharing of my story remained in the service of my client. Instead of telling my story, I leaned into her story, listening (carefully and attentively), using minimal encouragers and silence to create space for her to share with me the lens that she brought to this experience, opening to both commonalities and to important differences in our lived experiences.

Gina

Self-awareness and self-disclosure

Reflect on a time when a friend, family member, client, or someone else in your life shared a heartfelt experience (e.g., pain, good news, loss) with you, and you found yourself wanting to share your own story, but you chose not to do so. What was it about the encounter that had you listen and lean in fully, instead of sharing your story? How might this experience help guide you in your work with clients?

2. Enlisting Your Own Story

In Chapter 1 we invited you to begin to reflect on your own story, selecting an issue that is not easily resolved, but is not deeply emotional or traumatic. As you progress through each chapter, we encourage you to develop that story as if you were sharing it within the context of counselling. Drawing on the content from Chapter 2, consider the following prompts for self-reflection.

- What parts of this story might you find it most challenging to share with a counsellor? What it is about those parts of the story that enhances your sense of vulnerability, distrust, or hesitation?

- How do you experience care by loved ones?

- Think of a time when you experienced a care-filled engagement with another person and a time when you experienced a lack of care. How did these experiences differ? What was the impact on the relationship?

- What spoken or unspoken familial or cultural norms influence your degree of comfort in expressing emotion or sharing personal information with another person or, specifically, with a healthcare practitioner?

- What ways of being on the part of a counsellor would support the development of rapport? How are those ways influenced by familial or cultural norms?

- How might you discern between relational practices that fit for you personally and those that best serve the needs of each unique client you encounter?

3. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Macey’s story: Part 2

As you review this second instalment of Macey’s story, attend to how some of the themes that are addressed in this chapter resonate with what Macey is looking for in her counselling experience.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, February 11)

We invite you to draw on the story of Macey beginning with your own reflective process, considering the following questions:

- How might your self-awareness inform your ongoing role as counsellor in relationship with Macey?

- How might your self-reflections on your own story inform you as you purposefully develop rapport with Macey within an ethic of care?

- What attitudes, knowledge, or skills introduced in this chapter seem most important in working with Macey, taking into account her cultural background, her experiences within her family of origin, and her desire to learn more about Indigenous ways of knowing?

- Choose two important parts of the story that Macy shared, and create a paraphrase that would communicate to her that you are listening to, and engaged in, her story.

- What information might it be important for you to be transparent about with Macey at this point in the counselling process? How would you communicate that information?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

In each chapter, we have integrated learning activities and reflections to encourage you to personalize the content and to support your continued competency development. However, it is challenging to implement and build proficiency with microskills and techniques on your own. So, we have included additional applied practice activities in most chapters; these practice activities require you to work with another person (e.g., class peer, colleague). They are also intended as applied practice activities for use in college or university courses.

A. Optimizing the Applied Practice Activities

Please take a moment to watch our introduction to the applied practice activities. We use the word lab in this video because these activities may be used within the lab portion of a counselling skills course. We position the learning presented in this ebook in the context of these applied practice activities, attending in particular to the importance of critical reflection on client-centred practice and avoidance of cultural appropriation.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2023, May 15)

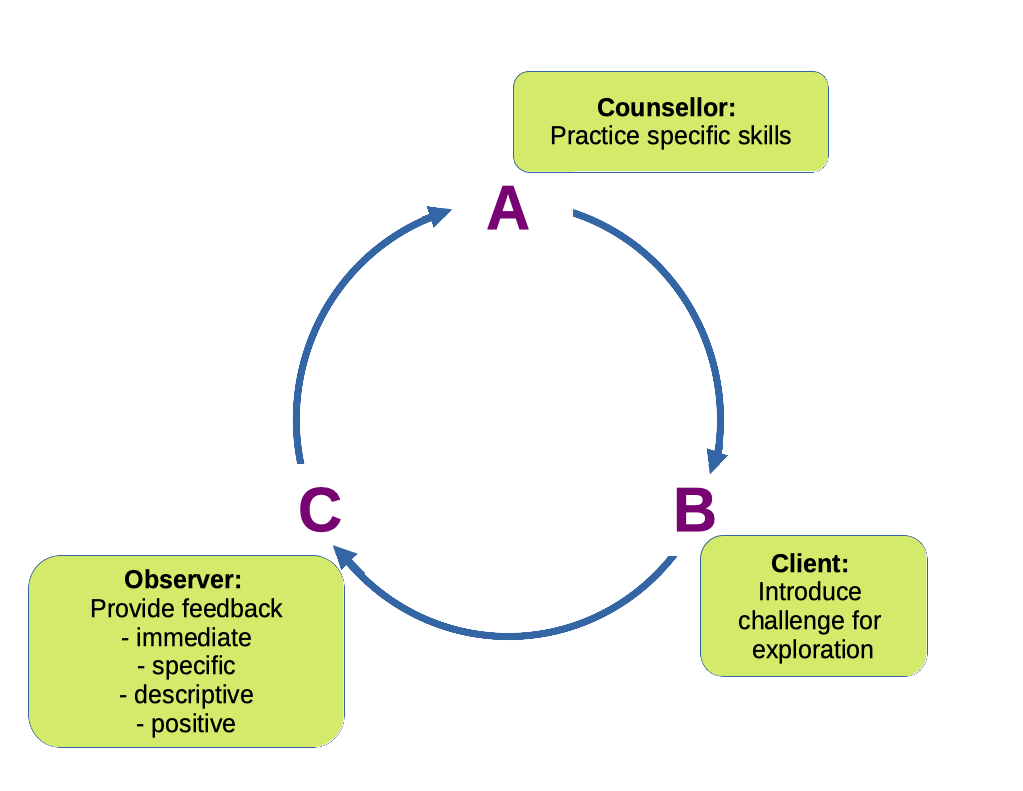

The following learning activities have been designed for a virtual learning environment (i.e., synchronous skills practice through videoconferencing software). However, these are easily adapted for use in face-to-face learning environments. For most activities, learners will complete two rounds of skills practice, and move between roles of counsellor and client. These practice activities can also be completed in triads, in which case learners would rotate through three roles: (a) counsellor, (b) client, and (c) observer.

Figure 3

Triad Model for Counselling Skills Practice

1. General Instructions

- The applied practice activities in each chapter are designed to take between 2 and 3 hours to complete. This first lab is a bit shorter to ease you into the applied practice. Your learning may be strengthened by breaking your practice session up into several short sections, whenever possible, to allow time for reflection.

- You may want to print out the applied practice activities before you begin your practice session, so they are readily available.

- Consider recording each activity you engage in during the applied practice sessions. This will allow you to track your development of proficiency with the skills over time and to attend to your nonverbal as well as verbal behaviour.

- We suggest that person in the role of counsellor do the recording. This ensures that the video remains on their device, and places the responsibility on them for safe and ethical storage of their skills practice sessions. If you are completing these activities as part of a university or college course, please check with your instructors about the specific ethical practices related to recording, storing, and disposing of practice videos.

- Please read through each of the activities before you meet with your partner to ensure that you are prepared to engage in the practice session, paying particular attention to the Preparation sections (we have put them in purple, so they stand out).

2. Assuming the Client Role

If you are using these applied practice activities as part of a university or college course, attend to the specific guidelines provided for your role as client. Some instructors may prefer that you engage in role-play (i.e., that you make up content for your role as client). However, we encourage you to bring your full self to the learning process. Instead of playing a role, if possible, share honestly challenges that you are encountering in your work, education, relationships, or other contexts. However, please maintain appropriate boundaries by excluding issues that hold high emotional weight, reflect traumatic events in your life, or are deeply personal.

If something comes up in a practice session that triggers an intense emotional reaction, have a plan in place with your practice partner that specifies what you need in that moment (e.g., postponing the practice session, talking about what happened and how to avoid it in the future, seeking out additional supports).

3. Responsive Feedback

Your relationship with your practice partner(s) is intended to mimic a client–counsellor relationship. We strongly encourage you to treat this relationship with the same dignity, respect, and responsivity that you would relationships with your clients. It is important to be honest in providing feedback to the person practising their skills; however, there are growth-centred ways of giving feedback that will optimize your shared learning. Here are some pointers:

- The following elements make feedback more effective:

- Be specific. It is much more helpful to state clearly what the counsellor did or did not do than to say simply, “Great job!”

- Be descriptive. Offer enough detail that the counsellor can build on your feedback to try something different the next time. For example, you might say, “The first part of your question was clear and concise. I think I would have been able to respond at that point without the additional explanation.”

- Be immediate. Provide your feedback as soon as you complete each applied practice activity. It is much easier to integrate feedback that follows directly after an interaction.

- Be nonevaluative. It is possible to be honest in your feedback without being evaluative. So, rather than saying: “You really missed the mark by . . . ,” or “Your paraphrasing was really great”; you might say: “You wanted to focus on only paraphrases, and three of the four statements you made were paraphrases,” or “When you used transparency at that point in the conversation, it really helped me to see . . .”

- Feedback is also more valuable if the person in the role of counsellor is specific about the type of feedback they are seeking in a particular practice session. Sometimes this specificity about practice goals will be set in the activity instructions; however, as you progress in your learning, you will get a better sense of your areas for continuing competency development.

- Working together in these applied practice activities involves risk-taking. In the client role, you are encouraged to talk about real issues, which enables you to practice vulnerability. In the counsellor role, you are opening to feedback, not only in terms of your use of particular microskills and techniques, but also in terms of your ways of being with clients. Please be gentle with yourselves and with each other.

- Come up with a way to track time during your practice sessions. Most often you will do two rounds of practice per activity (one each as counsellor), and the suggested times for each practice round are provided. You are welcome to do additional practice. However, staying within the practice guidelines for each activity will ensure you can complete them all within our goal of 2–3 hours of applied practice per chapter.

B. Responsive Microskills

1. Engagement and Curiosity

(15 minutes)

Skills practice

For this first applied practice activity, assume you are having a peer-to-peer, not a counsellor–client, conversation. Use this as an opportunity to get to know your partner a bit. Take turns enacting each of the roles below. Choose one person to practice recording these short interactions (3–4 minutes each). Share the video with the other person after your session.

- Speaker: Describe something you are passionate about that you think might interest your partner (e.g., a hobby, a cultural practice, a family tradition, a travel experience).

- Listener: Do not think about your microskills. Simply inquire about the experience, elicit a description of aspects of the experience that interest you most. Try to approach the experience with a sense of openness and genuine curiosity.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback to each other on the degree to which you were able to demonstrate active engagement, genuine interest, and an ethic of care.

2. Curiosity, Genuineness, and Authenticity

(20 minutes)

Skills practice

Continue with your peer-to-peer conversation. This time, the other person should practice recording your interactions. Brainstorm topics that the other person finds as uninteresting as possible (e.g., the drive to work or school, making breakfast, walking the dog, watching a child’s TV show, or other innocuous and commonplace aspects of life). Each take a turn in the speaker and listener roles below. Give yourselves long enough that you have to stretch to continue your inquiry in a genuine way (i.e., 4–5 minutes).

- Speaker: Describe something mundane from your life in which your partner has little or no interest. Offer enough detail to provide a foundation for counsellor responses, but do not keep talking unless the listener actively engages you in the dialogue.

- Listener: Use only minimal encouragers and paraphrasing. There may also be moments when silence is the most appropriate response.

- Remember, a paraphrase involves either (a) repeating key words or phrases expressed by the client or (b) using very similar wording that does not add new meaning.

- Lean into the speaker’s lived experience with genuine and authentic curiosity.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Provide feedback to each other on the degree to which you sensed genuine interest from the listener.

- There are times when client stories may not be that interesting to you. Brainstorm situations or topic areas in which you might be most challenged to stay present, to demonstrate genuine curiosity, and to listen openly to clients.

In later chapters, we will introduce different domains of client lived experiences. What you will likely notice if you stick to minimal encouragers and paraphrasing is that the client defaults to the domain in which they are most comfortable. As the speaker or listener in these first two activities, did you talk mostly about (a) behaviours or activities, (b) relationships with other people, (c) thoughts and beliefs, or (d) emotions and sensations? This is important information to add to your evolving self-awareness. Pay attention to this information as you move through the learning activities in this ebook.

3. Transparency As a Foundation For Rapport Building

(20 minutes)

Preparation

In advance of your practice session, identify a topic you are willing to talk about as the client. Remember to exclude issues that hold high emotional weight, reflect traumatic events in your life, or are deeply personal. You are welcome to use the presenting concern you selected for the Enlisting your own story reflective practice in Chapters 1 and 2.

Skills practice

Consider how you might approach the first few minutes of an encounter with a new client, drawing on your learning about ways of being and rapport building in this chapter. Engage in the dialogue for 4–5 minutes to give yourself enough time to try out the skill of transparency. Switch roles and repeat.

From this point forward, only the person in the role of counsellor should record their skills practice. We strongly encourage you to record all practice activities.