Chapter 9 Conceptualizing Client Lived Experiences: Client Contexts

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Mateo Huezo, Janelle Baker, Simon Nuttgens, and Michael Hart

In this chapter we add another layer of understanding to client challenges and preferences by inviting consideration of the broader contexts of their lived experiences. This contextual or systemic perspective provides an opportunity for clients to consider sociocultural influences on their health and well-being. It opens the door to recognizing when the challenge they are encountering arises from oppressive or health-limiting narratives, norms, or institutional structures, rather than from within their thinking, emotions, competencies, or internal resources. As you move through the chapter, keep in mind both the influence of these external factors on the ways in which the challenge is conceptualized as well as the possibilities open to the client for envisioning their preferred lived experiences. We begin by exploring the ways in which identities and experiences of gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation are contextualized by sociocultural discourses and norms, attending to both the intersections of client identities and the intersectionality of cultural oppression.

Figure 1

Chapter 9 Overview

RESPONSIVE RELATIONSHIPS

A. Intersectionality

We have argued throughout this ebook that both counsellor and client are complex cultural beings, defined in part by the intersections of their cultural identities (i.e., age, ability, gender identity, sexual orientation, social class, religion, spirituality, ethnicity, Indigeneity) (Collins, 2018d). If you are not familiar with the concept of intersectionality, you may find this short video useful.

My intersections

On a scale of 1 (not at all) to 10 (always), rate the degree to which you are conscious on a daily basis of the various dimensions of your own cultural identities and their intersections. Then, as you watch this short video, attend to the ways in which the intersections of your cultural identities amplify your privilege or reinforce your position of marginalization. You may experience both, across time and context.

© Teaching Tolerance, Southern Poverty Law Centre (2016, May 18)

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc2/#myintersections. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

As noted in Chapter 1, Norcross and Wampold’s (2018) research on evidence-based relationships and responsiveness identified client ethnicity as well as religion and spirituality as two of the factors for which there is demonstrable evidence of the need to adapt counselling relationships and practices to be responsive to each client. They also identified gender identity and sexual orientation as important factors that have not yet been adequately investigated, based on there not existing sufficient number of empirical, randomized control studies to meet their criteria for meta-analyses (Norcross & Wampold, 2018). Two articles in this special edition of the journal highlighted the available research on the importance of attending to gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation (Budge & Moradi, 2018; Moradi & Budge, 2018). It is noteworthy that the impact of social class, age, and ability were not explored at all. However, there are many other sources of support in the multicultural counselling and social justice literature for responsive relationship-building across multiple dimensions of client identities and social locations (Collins, 2018c, Paré, 2013; Audet & Paré, 2018; Ratts et al., 2015; 2016).

1. Gender, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation

Our intent is not to provide a review of the literature on working with 2SLGBTQIA+ people. We encourage you to refer to our suggested list of multicultural and social justice resources in Chapter 1 for more detailed exploration of those principles with which you are less familiar. Rather, we will highlight some of the relational principles and practices identified by Budge and Moradi (2018) and Moradi and Budge (2018) that have particular importance for counselling women and clients from gender and sexual minority populations. We adapt the principles below to the conceptual frameworks and language choices in this resource, drawing also on Collins (2018c).

- Create a welcoming environment that is explicitly inclusive of 2SLGBTQIA+ people.

- Adopt an antipathologizing lens, which includes a critical examination of your own assumptions and biases.

- Stay up-to-date on gender inclusive and antipathologizing language, actively choosing to honour client choices about personal pronouns and descriptors of identities and relationships.

- Engage in collaborative exploration of client lived experiences with a stance of cultural curiosity and not-knowing that privileges clients’ knowledge, values, and worldviews.

- Support clients to deconstruct power inequities that result in sociocultural marginalization, including explicitly addressing power dynamics within the client–counsellor relationship.

- Assess the salience of culture to ensure that you do not inappropriately position gender identity or sexual orientation as the cause of client challenges.

- Assume an affirmative and strengths-based approach that foregrounds client strengths, competencies, responses, and resiliency.

- Apply the lens of intersectionality to invite consideration of the unique and fluid interplay of various dimensions of client cultural identities and social locations.

- Apply a contextualized, systemic lens to attend to the socio–cultural–political contexts of clients’ lives, foregrounding experiences of oppression and stigma.

- Engage in affirmative practices to acknowledge power inequities and to foreground client resistance.

- Integrate analysis of sociocultural, institutional, and systemic influences on client lived experiences (e.g., gender analysis, power analysis) to externalize and position the locus of control and responsibility for client challenges in the broader contexts of their lives.

- Apply a social justice framework that opens the door to systems-level change processes, including advocacy and activism in exploring client preferred outcomes.

These principles are clearly transferable to working with all clients, whether or not they identify as a member of 2SLGBTQIA+ communities. They suggest a convergence of practices related to responsive relationships and responsive conceptualization of client lived experiences that support our arguments in this ebook. In this chapter we pick up on principles 8 through 12 to apply a contextualized, systemic lens to client challenges. We attend specifically how clients’ intersectional identities and social locations necessitate understanding of the influences of organizations, communities, institutions, and broader social, cultural, and political systems on the challenges they face and the possibilities they envision for preferred futures.

B. Applying a Contextualized, Systemic Lens

One of the emergent themes in the multicultural and social justice literature is the importance of applying a contextualized, systemic lens to understanding client presenting concerns, to developing shared meaning-making about the challenges they face, and to envisioning their preferred futures (Audet & Paré, 2018; Collins, 2018a; Ratts & Pedersen, 2014). In this section we invite your consideration of a couple of ways in which client challenges may be located (in terms of both etiology and possibilities for change) in the contexts of their lives.

1. Deconstructing Socio–Cultural–Political Influences

In Chapter 8 we invited consideration of client views of health and healing as an important element of clients’ worldviews. When working with Indigenous clients, applying a systemic lens can involve looking beyond the sphere of human interactions and systems to consider the connections of clients to land and place (Dupuis-Rossi, 2018; Fellner et al., 2016; Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRCC], 2015). Land displacement for Indigenous peoples on Turtle Island began with, and continues through, colonization and is now complicated by climate change. In 2019 24.9 million people from 140 countries were displaced because of ecological or climate disasters (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2020). It is important to be conscious of these environmental systems as you consider client-centred views of health and healing when you work together to co-construct a shared understanding of the challenges they face and the ways in which they would like their lived experiences to be different.

Contributed by Janelle Baker

In this video Janelle talks about her own experience and her research within Indigenous communities experiencing loss of land and ecosystems. Without attending to the broader systems that influence client’s lives, it would be impossible to begin to build a shared understanding of a profound experience like ecological grief.

© Janelle Baker (2021, March 26)

Click here for a transcript of this video.

In the video ecological grief is defined as grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems, and meaningful landscapes, due to acute or chronic environmental change. Indigenous healers and counsellors speak about the importance of land-based understanding of lived experience and healing processes. As Janelle points out, ecological grief will affect more and more people as climate change continues. As you reflect on the experience of ecological grief, consider how you might incorporate inquiry about land-based identities, experiences, and losses into your conversations with clients.

As we reflect specifically on building care-filled and client-centred with 2SLGBTQIA+ peoples in this chapter, it is important to step back to consider the ways in which socio–cultural–political factors often impact their lived experiences. One area where client intersectionalities and social locations play out is the complex interplay of gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and religion. Regardless of their own spiritual beliefs or religious affiliation, counsellors engaging in responsive relationships with clients must be willing to hold the space for clients to express the ways in which they have experienced discrimination or cultural oppression that stemmed from religious views and organizations, including the involvement of religious organizations in colonization (TRCC, 2015), the use of conversion therapy with 2SLGBTQIA+ peoples (Canadian Psychological Association, 2015), or other forms of persecution based in religion (Saleem, 2018).

Working with faith and spirituality in 2SLGBTQIA+ care

Contributed by Mateo Huezo

Mateo begins by positioning his own experience of spirituality as a Salvadorian in the context of his intersectionalities. As you watch this video, attend to the ways in which Mateo balances the potential contribution of religion and spirituality to interpersonal and relational well-being for members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community with the potential losses to self and others that result from their experiences of rejection and discrimination by religious communities.

© Mateo Huezo (2021, May 24)

Reflections:

- Reflect critically on the complexities for clients in navigating cultural, religious or spiritual, and sexual and gender minority identities.

- If you are less familiar with sexual and gender identities, review the definitions of two-spirit, cis/cisgender, trans/transgender, het/heterosexual.

- How do your own religious or spiritual beliefs contribute to your health and well-being? In what ways do they affirm or undermine your sexual and gender identity?

- What values or attitudes from your religious or spiritual worldview support life-affirming and growth-fostering relationships with sexual and gender minorities?

- Which values or attitudes might stand in the way of you providing competent and culturally responsive services with sexual and gender minorities?

- What did you learn from the counsellor reflections about yourself and your readiness for work with sexual and gender minority clients? How might you build on your strengths and remediate the challenges that emerged?

For those counsellors who hold religious privilege (i.e., a dominant Christian faith), it may be emotionally challenging to bear witness to client experiences of oppression without being triggered into cultural countertransference (i.e., anger, defensiveness, judgment) stemming from personal values and beliefs. Counsellors demonstrate professionalism, respect, and compassion by actively supporting clients to talk openly about, and express their anger toward, white and settler privilege, the role of the Christian church in colonization, discrimination toward 2SLGBTQIA+ persons by various religious institutions, and so on. These are not easy conversations, but without them building effective and responsive relationships can be impossible. The most powerful tool for avoiding countertransference is foregrounding the ethical mandate that all your engagement within the client–counsellor relationship is in service of the client’s health and healing. We will talk more about transference and countertransference in Chapter 11.

The practice principles adapted from Budge and Moradi (2018) and Moradi and Budge (2018) in the first section of this chapter reinforce the importance of the counsellor in creating a culturally safe and responsive environment for all clients. Applying a contextualized, systemic lens to client lived experiences necessitates counsellor consciousness of the social, economic, environmental, institutional, and political inequities of society (Hargons et al., 2017; Roysircar et al., 2018). It also requires a depth of self-understanding and self-reflection that goes beyond surface acknowledgement of social inequities and injustices. Through this next video we invite you, once again, to reflect on what you may need to examine within yourself to clear a space to be fully present to your clients.

Contributed by Dr. Michael Anthony Hart (in conversation with Gina Ko)

In this video, Dr. Michael Anthony Hart highlights racism as a form of cultural oppression. He positions racism as a complex concept whereby one is not simply racist or nonracist. He argues that “racism is a verb,” because racism is about action (inaction) and about things that are done (or not done). Hence, self-reflection is necessary to keep continuously learning (and unlearning) about racism.

© Michael Hart (2021, June 2)

After watching this clip, reflect on the following questions:

- What does it mean to you that racism is a verb?

- What do you discover in yourself as you reflect on the complexity of racism?

- How would you sit with a client to explore their experiences of racism?

- Where in your life might you do things differently, because of positioning racism is a verb?

- How would you apply this principle to other *isms (e.g., transphobia, sexism, ageism, classism)?

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

A. Conceptualizing Client Lived Experiences

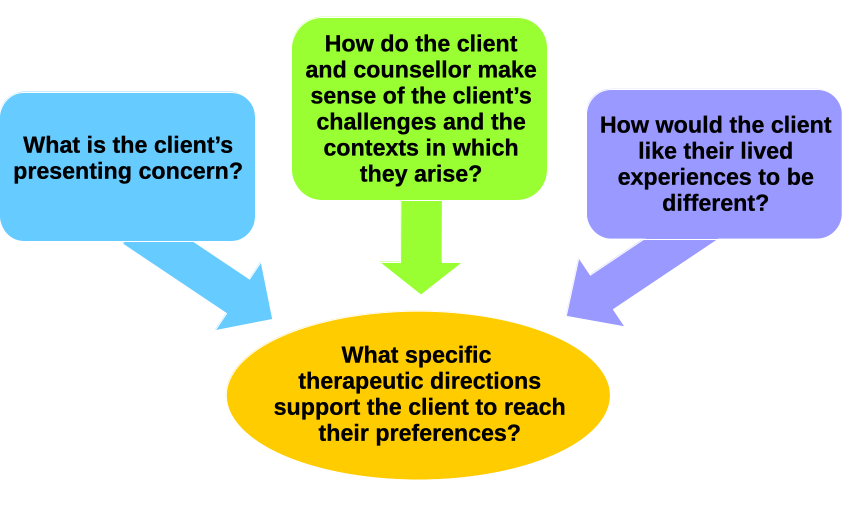

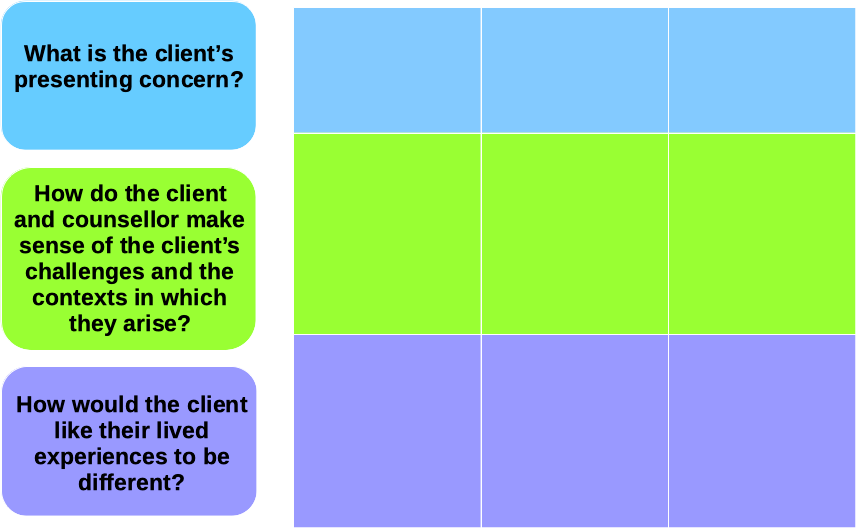

In this chapter we return to our focus on the second question in Figure 2 (How do the client and counsellor make sense of the client’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise?) by applying the contextualized, systemic lens introduced above. Our intent is to ensure that the various contexts of clients’ lives are fully examined, particularly as potential sources or reinforcements of the challenge. This examination of socio–cultural–political influences on client lived experiences also extends to the possibilities they envision for preferred futures, the third question (How would the client like their lived experiences to be different?).

Figure 2

Culturally Responsive and Social Just Conceptualization of Client Lived Experiences

1. Contextualizing Challenges and Preferences

The process of contextualizing challenges and preferences begins with disrupting the assumptions that the source of client distress is intrapsychic or even immediately interpersonal. Instead, opportunities are generated by the counsellor to consider the potential influence of the broader contexts of clients lives. In particular, this involves examination of experiences of cultural oppression as well as potentially more subtle encounters with, or internalization of, sociocultural narratives that are health- and life-limiting. These oppressive narratives may also influence the possibilities clients are able to generate in terms of their preferred presents or futures.

The story of Giselle

Consider the following care scenario, in which the client presents with concerns about returning to work following an injury. Attend to the various openings provided by the client to explore the sociocultural contexts of their lived experiences.

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, March 26)

Questions and prompts for reflection:

- Take a moment to pause and reflect honestly on potential assumptions or biases that you may bring to the conversation with Giselle.

- Then identify as many avenues as possible for exploring the contextual, systemic factors that may have an influence on their story.

- What sociocultural narratives or discourses might you want to explore with Giselle?

- Based your first impressions (hypotheses) how might you answer each of these questions? (We are intentionally asking you for a guess based on very limited information.)

- How might you and Giselle make sense of their challenges and the contexts in which they arise?

- How might Giselle like their lived experiences to be different?

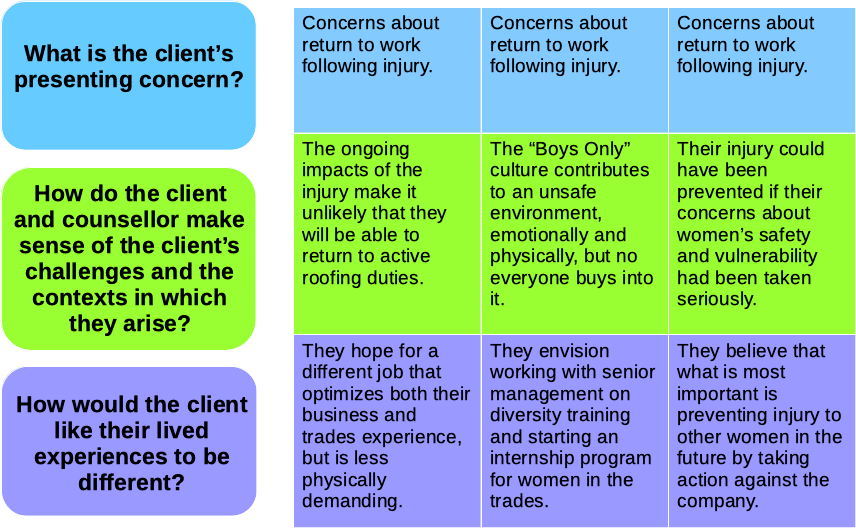

Next consider the various responses to these questions provided in Figure 3. Although the presenting concern remains the same, the shared understanding of the challenge and the client’s preferred outcomes differ in each column. Imagine the conversations between counsellor and client that may have resulted in each of these conceptualizations. Notice how the locus of control and responsibility for the challenge (i.e., the client factors versus the contexts of their lived experience) shifts across the three versions in Figure 3.

Pathways Through the Process of Conceptualization Client Lived Experiences

Finally, consider other alternatives for the second and third step in the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences, drawing on the sociocultural narratives or discourses you identified in response to the video. The point of this activity is to reinforce that (a) there is no single, predetermined, or right pathway from client presenting concern, to their challenge, and to their preferred outcomes. One of the factors that can substantively influence the shared conceptualization between counsellor and client is purposeful attention to sociocultural narratives and contexts.

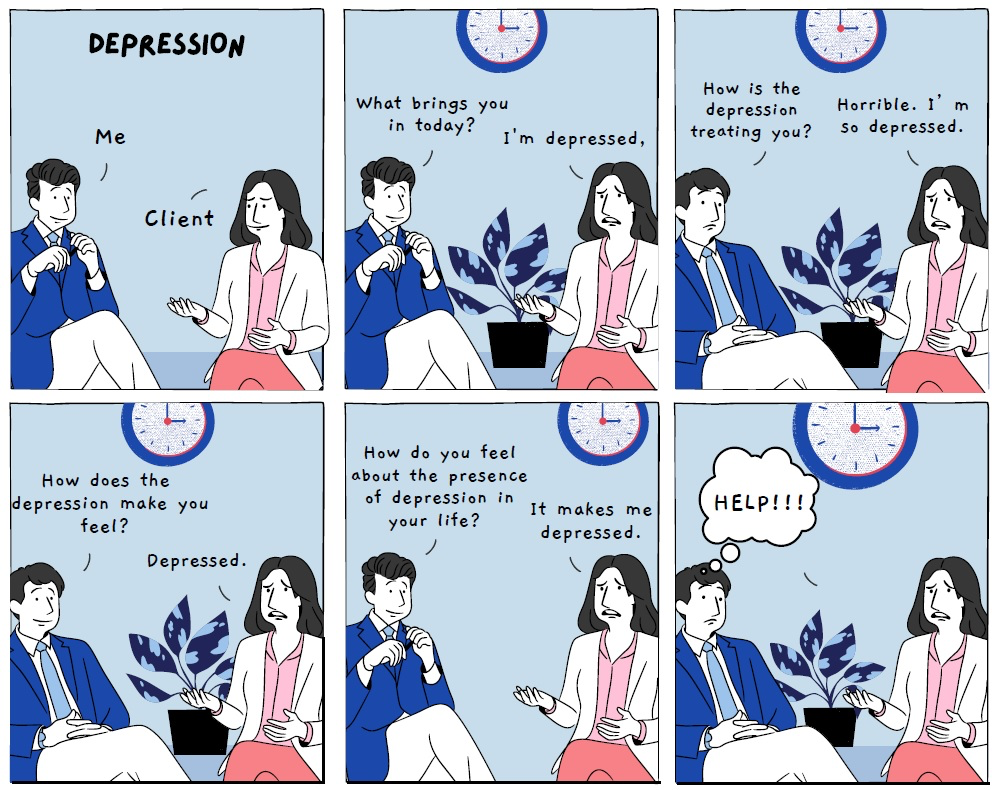

Contextualized, systemic lens

As you explore the techniques introduced in this chapter, we invite you to keep in mind the context of clients’ lives and the influences of that context on both challenges and preferred outcomes. We have provided a couple of short clips below to demonstrate what it looks like to ignore the various ecosystems that relate to client perceptions or experiences of their challenges and what it looks like to attend intentionally to those contexts.

Applying a contextualized, systemic lens

Decontextualized and individualist focus

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, June 1)

Contextualized and systemic focus

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, June 1)

MICROSKILLS AND TECHNIQUES

The Responsive Microskills and Techniques summary provides a quick reference to each of the techniques introduced in this chapter.

A. Responsive Techniques

Each of the techniques in this chapter invites consideration of a broader lens on client challenges by attending directly to the contexts of their lives. Together they also build a foundation for continuing to envision preferred futures, as introduced in Chapter 8. As you reflect on these techniques, consider how client views of health and healing, relationship to time and place, intersectional identities, and social locations might influence the implementation or adaption of each technique to client context.

1. Exploring Sociocultural Contexts

As you work with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds, you will inevitably encounter client presenting concerns that appear to be embedded in, or influenced by, the sociocultural contexts of their lives. This is a fundamental principle of multicultural counselling (Collins, 2018a; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016), feminist counselling (Brown, 2010; Enns et al., 2013; Worell & Remer, 2003), narrative therapy (Freeman & Combs, 1996; Nyland & Temple, 2018; White & Epston, 1990), relational-cultural theory (Jean Baker Miller Therapy Institute, 2017; Jordan, 2010; Lenz, 2016; Singh & Moss, 2016), and other approaches to practice that attend to social injustices and other social determinants of health. Paré (2013) highlighted the continuous back-and-forth movement in counselling conversations between the client and the contexts of their lived experiences. This interface and interplay of client and context influences not only how they view health and healing, more generally, but also how they make meaning of the particular challenges they confront within and across the various contexts of their lives. The technique of exploring sociocultural contexts involves examining the various layers of interpersonal, contextual, and systemic environments in which client challenges emerge and play out.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Exploring sociocultural contexts

Featuring Gina Ko and Sandra Collins

In this video Gina picks up on Sandra’s preference to bring her whole self forward in a more consistent way (see Chapter 8 videos) and invites Sandra to explore what this might look like in various contexts of her life. Together they decide to focus on the interpersonal barriers for Sandra in expressing mind–body–spirit–heart integration as well as her existing supports.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, June 6)

We chose a topic that was a bit more subtle in terms of sociocultural influences on client experiences for this video because it is always important to offer up for consideration the possibility that the problem resides in the contexts of clients’ lives, rather than within the client themselves. Up to this point, Sandra appears to have positioned the problem as located in her own ways of coping and being.

Reflections:

- Notice how Gina integrates the microskill of offering affirmations as a way of supporting Sandra in this experience. How does her use of this microskill make a difference to their conversation and relationship?

- Gina introduces the concept of curiosity, which resonates for Sandra (i.e., co-constructing language). How does this support further meaning-making in their conversation?

- How does the conversation about locus of control support Sandra to refine her vision for centring her whole self in relationships?

To demonstrate the ways in which the four techniques in this chapter can be used together to accomplish the overall goal of contextualizing client challenges and preferred futures, we created the story of Bennu which is presented in four parts. Part I demonstrates the technique of exploring sociocultural contexts.

Bennu’s story Part I

In this first part of Bennu’s story, Bennu encounters the counsellor for the first time. Notice the ways in which various aspects of Bennu’s cultural identities come into play. Attend also to the ways in which the counsellor opens conversation about the sociocultural contexts that influence Bennu’s current sense of self as well as the possibilities they envision for the future.

© Sandra Collins (2021, June 3)

The counsellor could have continued to explore sociocultural contexts in increasing depth with Bennu. However, we kept the video short to allow you the opportunity to imagine where you would take this conversation.

Questions for reflection:

- What are you curious about as the video draws to a close?

- What contexts remain unexplored, or only thinly described, at this point?

- Choose a point in the video at which you would incline toward a different line of inquiry with Bennu. What specific microskills might you use to thicken your shared understanding of Bennu’s sociocultural contexts?

2. Deconstructing Sociocultural Narratives

The importance of deconstructing sociocultural narratives was noted in the list of practice principles adapted from Budge and Moradi (2018) and Moradi and Budge (2018) earlier in the chapter. Deconstruction is a common process in feminist therapy, narrative therapy, and many models of multicultural counselling (Collins, 2018d; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016). Deconstruction is also an important foundation of decolonization (Dupuis-Rossi, 2018; Dupuis-Rossi & Reynolds, 2018). It involves positioning client experiences and perspectives within the broader context of dominant and nondominant sociocultural discourses and narratives. The steps/processes below are adapted from Paré (2013) and Worell and Remer (2003). In this case, we do not provided specific examples of counsellor verbalizations, because the technique has a number of distinct steps or processes, and you will already have a solid grasp on the various microskills at this point.

| Description | Purpose | Steps/Processes |

|

|

|

We have positioned deconstruction as a conversational tool for both (a) refining shared understanding of client challenges and the contexts in which they arise and (b) developing a picture of client preferred futures by identifying how they would like their internalized messages and engagement with external discourses to be different. The five steps or processes (Column 3) above provide a foundation for moving into what is often a sixth step in the process of deconstruction: Co-constructing change processes to facilitate these preferred outcomes (Collins, 2018b). This final step is beyond the scope of this ebook.

Deconstructing sociocultural narratives

In the video below notice how Sandra invites Gina into critical analysis of the influence of sociocultural narratives related to gender, and then more specifically, to mothering.

© Sandra Collins & Gina Ko (2021, May 1)

Reflections:

- At what points in this conversation might you have suggested a different direction? What might you have discovered if you had followed that path?

- How might the sociocultural discourses that emerged for Gina potentially shape both the shared understanding of her challenge and her preferred futures?

Applying gender role analysis to the intersections of gender and ability

To provide additional practice specifically with deconstructing gender, review the steps in the feminist practice of gender role analysis (adapted from Worell and Remer, 2003).

- Elucidate messages received through gender role socialization.

- Trace those messages back to their origins in dominant or nondominant social discourses.

- Analyze critically the positive and negative consequences of these gendered narratives.

- Reflect on the degree to which these messages have been internalized.

- Select actively from among those gendered messages those that the client wants to maintain or discard.

- Co-construct change processes to facilitate these preferred outcomes.

Then, reflect critically on the vignette below.

Anna is a professional athlete competing in events on both the national and international level. She presents as bright, articulate, and confident. She changed the focus of her athletic endeavours following a serious ski accident eight years ago, in which she broke her back and lost the use of her legs. She now competes as a snow boarder in paraplegic events.

She talks comfortably about her accident and the process of rebuilding her life. She has lots of social supports and resources. She has been completing her graduate education in health studies, while training rigorously for upcoming sporting events.

When you ask what has brought her to the counselling session, she hesitates and then explains that she is struggling to get back into dating. She has a lot of positive relationships with male friends, but even if she is interested in something more, things never seem to move in that direction. She seems to have become “one of the boys,” which she enjoys, but this is no longer enough to meet her needs. Before her accident, she had no difficulty in this area and always had a boyfriend or a number of guys that she was dating casually.

Anna notes that most of her current social relationships revolve around sports, and the athletes involved in the paraplegic games are predominantly men. She does have a few close female friends who are very supportive, but she has not talked with them in depth about her concerns.

Apply the principles of gender role analysis drawing on the following questions:

- In what ways might the gendering of professional sports and disability come into play in this scenario?

- How might the intersections of gender and ability be playing out in Anna’s lived experiences?

- What broader sociocultural discourses related to gender and ability might you consider exploring with Anna?

- What types of gendered or ableist assumptions might you need to attend to so that you don’t bring them forward into your relationship with Anna?

- How might this analysis of gender support Anna in moving forward with her goals?

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc16/#genderability. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Bennu’s story Part II

In this second part of Bennu’s story, the therapist starts by thickening Bennu’s description of “the box” as they co-construct this metaphor for the challenge Bennu is facing. This lays the foundation for externalizing the challenge, which we will pick up on more fully in Part IV. The therapist then invites Bennu into the process of deconstructing sociocultural narratives, following Bennu’s lead about those that are most important in-the-moment.

© Sandra Collins (2021, June 3)

Reflections:

- How does developing a thick description of “the box” support detailed exploration of the gendered messages that Bennu has encountered and, to some degree, internalized?

- In what ways does this visual metaphor provide a meaningful anchor for their conversations across counselling sessions?

- Choose one of the other areas that they identified (culture or ability), and reflect on how you might engage in the process of sociocultural deconstruction with Bennu in that area.

3. Reframing

Human beings are all susceptible to holding narrow or compartmentalized views of their lived experiences. They naturally default to interpreting their experiences in light of what they see around them on a daily basis, their socialization, and their particular worldview. Reframing is about expanding the parameters of client perceptions or inviting them to try on new lenses that might enable them to shift perspectives and to open up to new possibilities. Reframing may also allow them to position their experiences within broader contexts that they may not have considered. Reframing is a common practice in feminist therapy, where the emphasis is often on shifting from a victim-blaming position to a consideration of the sociocultural factors that are at root of the challenge (Brown, 2010). Reframing is sometimes referred to as influencing; however, we choose not to use terminology that is a counsellor-centric. The language of reframing has a more invitational tone and invites the client to explore, reflect on, and critically analyze the fit of alternative perspectives.

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Notice from the examples below how the client is invited to engage actively in the reframing process rather than being handed an already-formulated lens by the counsellor. This does not mean that the counsellor is not an active participant in the co-construction of alternative perspectives; instead, it means that the client is always given the final say on what fits or does not fit for them.

Reframing: Starting with client’s cultural meanings

In this video Sandra continues a previous conversation with Yevgen about his challenge in managing work demands. Notice how she introduces the technique of exploring cultural meanings (Chapter 8) at the 3:25-minute mark and then draws on this foundation to move into the technique of reframing at the 5:58-minute mark.

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, June 1)

Sandra purposefully grounds the reframing process in Yevgen’s cultural context and lived experiences, inviting him to offer up new language that they can build upon together, which results in a shift from “perfectionism” to “responsibility to students.”

Bennu’s story Part III

In this third edition of Bennu’s story the counsellor begins by continuing to gently externalize Bennu’s challenges drawing on the metaphor of “the box.” Notice how they then focuses on the messages that Bennu has internalized, pointing to the ways in which these messages confine and define Bennu. The counsellor then invites Bennu to consider an alternative way of looking at the situation with their parents.

© Sandra Collins (2021, June 4)

Reflections:

- What shifts for Bennu as Bennu experiments with the idea of not just sitting quietly in the box?

- How does the counsellor reinforce this shift by using a cultural metaphor introduced by Bennu in the first session?

- In what ways does reframing function to open new possibilities for Bennu?

4. Externalizing

Externalizing is the process of separating the person from the challenge they are facing (Nyland & Temple, 2018): I am not a perfectionist—perfectionism sometimes ambushes me! The technique of externalizing evolved within narrative therapy (White, 2007; White and Epson, 1990); however, it supports responsive relationships and socially just conceptualizations of client lived experiences regardless of your theoretical orientation (Paré, 2013). Notice how this perspective-taking is very much about a relational stance, an expression of an ethic of care, in which the interplay between person and environment is acknowledged. Externalizing often involves naming the challenge in some way (e.g., “the box” in Bennu’s story) to allow the client to progressively position themselves as separate from, and in relational to, the challenge they face. By separating the client from their challenge, a door opens to uncovering new possibilities that are not available when the client sees themselves as the problem. From this one-step-removed position, it is easier to examine the negative repercussions of challenge in the client’s life.

Externalizing: There is no “right” choice of microskills

There are innumerable combinations of microskills on which the counsellor can draw to implement various counselling techniques. Take, for example, the exchange between counsellor and client in this first video, which demonstrates the technique of externalizing.

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, February 14)

As you can see, the counsellor’s part in the dialogue consists of a sequence of three microskills. Together, they construct the technique the counsellor is drawing on in-the-moment. The counsellor could have selected a different sequence of microskills to support the same purpose: externalizing the client’s challenge.

© Sandra Collins & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, February 14)

We encourage you to begin to test out different microskills as you engage with these techniques, attending to the intention of each skill in the moment-by-moment dialogue with the client.

Most of us have an opportunity to provide a listening ear to others on an almost daily basis. The next time someone talks with you about a challenge in their lives, listen carefully for opportunities in the language they use or the way they frame their experiences to open the door for externalizing. If the person is agreeable, practice this technique. [We don’t recommend you do this in a counselling environment yet!]

| Description | Purpose | Examples |

|

|

|

Like all counselling skills, employing the technique of externalizing skilfully requires practice, and then more practice, to develop the fluidity required to be responsive in-the-moment to the client before you. Consider the reflections below by Simon Nuttgens on some of the potential challenges of embarking on externalizing conversations with clients.

Contributed by Simon Nuttgens

Externalizing conversations are virtually synonymous with narrative therapy (NT). The practice actually predates the naming of NT as a therapy, showing up in Michael White’s classic paper, “Pseudo-Encopresis: From Avalanche to Victory, from Vicious to Virtuous Cycles” (1984). It was here that White demonstrated the therapeutic potential of casting an externalized version of the problem as an oppressive entity, that is, as a foe that ought to be overcome. I would encourage all NT enthusiasts to read this early offering from White, taking note not only of his use of externalization, but also of his skilful use of creativity and humour to address playfully what is often experienced as an embarrassing and shame-inducing problem.

It wouldn’t be until the release of White and Epston’s seminal book, “Narrative means to Therapeutic Ends” (1990) that NT established itself as distinct approach to therapy. By the time I began my master’s program in 1995, the therapy world was abuzz with excitement over this new “postmodern” approach to therapy. And so it was that I, too, latched onto the excitement, viewing NT as not only a potent collection of therapeutic ideas, but also as an antidote to what I viewed as the stagnant waters of traditional counselling theory.

It turned out that it was much easier to fall in love with NT ideas than actually to put them into practice. In fact, a couple of years into my quest to become a NT therapist, I began to craft a paper, tentatively titled, “Confessions of a Narrative Therapist Imposter.” In the paper I planned to describe the myriad ways I had embraced the spirit of NT, with one glaring exception: I was terrible at facilitating externalizing conversations. Prior to every session I would study a list of externalizing questions I had constructed, along with the rough order in which they “ought” to be delivered, only to find myself procedurally adrift minutes into my session. I can recall with clarity my first ever attempt to externalize. I was at the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Education counselling clinic at the time, and my new referral was a mid-forties individual who sought help for depression. My externalizing conversation with them went something like this.

Click here for a transcript of this conversation.

Click here for a transcript of this conversation.

The externalizing conversation hadn’t even lasted a minute when I abandoned it for my best rendition of Carl Rogers. Unfortunately, however, the damage was already done. After about twenty minutes my client said they needed to leave, which they did and never came back. If I were to externalize externalization, I would have to say that it was getting the best of me! How might I transform it from foe to friend in my counselling practice?

The turning point (yes, this is a good news story) came when I ratcheted up another mainstay of NT practice: therapeutic letter writing! What I found was this. Even if I fumbled horribly in my use of externalizing conversations while in session, afterward I could always write a therapeutic letter that featured an externalized version of the problem, complete with elegantly posed follow-up questions for contemplation. I would then use this letter as a point of departure for the subsequent session. I could also expand into creative use of letter writing, for example writing a letter to the “problem” or from the “problem,” all the while honing my ability to use externalization to frame the therapeutic conversation.

Earlier I mentioned the use of written and pre-rehearsed externalizing questions. I should clarify that this did to a moderate degree help me to learn and integrate a collection of externalizing questions along with how and when they could best be used. What also helped in this regard was simplifying the range of client concerns that could potentially be externalized. When reading NT case studies, I found it somewhat intimidating to come across what seemed like very creative, if not convoluted, externalizations. For example, Michael White would sometimes use rather lengthy externalizations such as “The Living for Others Lifestyle.” In some instances, White would adopt an externalization and then check with the client to ascertain fit. In other instances, he would simply ask the client to name the problem, a practice which has become common and preferred among NT therapists. Furthermore, some NT therapists would employ multiple externalizations within a single question, such as, “How does Fear and Self-Doubt steal your Hope such that Insecurity comes around?” Try as I might, I never seemed to have the conversational dexterity to effectively use externalizations in this fashion. I was thus forced to simplify, choosing (in collaboration with the client) one word “problems” (e.g., Fears, Temper, Sadness, Nerves, Worry, Fits) and only using one externalization in any given therapeutic conversation.

Finally what I learned was that not every client concern is amenable to an externalizing conversation. For example, I rarely use externalizations when doing grief counselling. You, too, will likely find that its use seems to fit better with some client concerns than others. I am aware that this advice runs contrary to the beliefs of many NT proponents who contend that every therapeutic conversation can and should involve externalization. I believe, however, that even if the presenting concern is amenable to externalization, not every client will find this way of talking about the problem meaningful or helpful. As with any counselling relationship, it is critically important to adopt a collaborative posture with your client, taking care to assess the degree of fit between their preferences and predilections and the counselling strategies you are using.

Bennu’s story Part IV

Although the counsellor has been working on externalizing the challenge with Bennu from the first video onward, they take the process of externalizing further in this video by inviting Bennu to consider how Bennu might act upon, or in relation to, the challenge represented by the “the box.” By doing so the counsellor supports Bennu further to distance from the challenge.

© Sandra Collins (2021, June 4)

Reflections:

- In what ways did the process of externalizing open up new possibilities for Bennu that were not available when Bennu saw themselves as intertwined with, or the source of, the challenge?

- How did the process of externalizing support Bennu to begin to envision her preferred futures?

- After viewing the four parts of Bennu’s story, how might you respond to the following key questions in our model:

- How might you and Bennu make sense of Bennu’s challenges and the contexts in which they arise?

- How might Bennu like their lived experiences to be different?

We refer you to Dupuis-Rossi (2020), who offers a detailed description of how Indigenous practitioners, in particular, can apply some of the techniques in this chapter in their work with Indigenous clients to support the process of decolonization. Dupuis-Rossi offered an example of reframing a client’s internalized sense of failure as a failure of capitalism and colonialism. They noted that this reframe “resists mainstream psychology’s individualisation and privatisation of child sexual abuse [and other manifestations of colonial violence] and connects it to the systems of colonial oppression that cause this suffering for Indigenous people” (p. 8). Dupuis-Rossi supported the client to name and externalize these oppressive forces, which “opened up internal space for the next layer of healing” (p. 8). You may find the other examples in this article on the use of these techniques with Indigenous clients helpful.

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

A. Practising mindfulness

We invite you to open yourself to a mindfulness practice that follows from Mateo Huezo’s presentation on spirituality earlier in the chapter. In this activity Mateo extends the meaning of context by inviting the past into the present through connection with ancestors.

Mindfulness: Connecting with the Ancestors

Contributed by Mateo Huezo

In this mindfulness activity, Mateo invites you to connect with your own spirituality and heritage. Notice the distinction between grounding in the present (introduced in Chapter 5) and engaging the imagination in mindfulness practices. Consider carefully how you would assess with clients the appropriateness of this type of activity.

© Mateo Huezo (2021, May 24)

Reflections:

- What came into focus for you in your connection with your ancestors?

- What gifts have you received from your ancestors? What meaning do you make of those gifts in the here-and-now?

- In what ways was this activity helpful or healing for you? How might you use or modify this activity in your work with clients?

B. Enlisting Your Own Story

As you continue to evolve your own story, reflect on the influence of the broader contexts of your lived experiences.

- How might considering these contexts, dominant or nondominant sociocultural discourses, or other systemic factors alter your current understanding of the challenge you are facing or your sense of preferred futures.

- How might you draw on the techniques of exploring sociocultural contexts, deconstructing sociocultural narratives, or reframing to deepen your understanding of your challenge and preferences?

- Take a moment to give the challenge you are facing a name or to characterize it by a personally or culturally meaningful metaphor.

- Imagine using the technique of externalizing to separate yourself from the challenge called “. . . “: How might you actively distance yourself from, negotiate with, navigate around, minimize the influence of, or otherwise approach, the externalized challenge?

Conceptualizing client lived experiences: Your challenges and preferences

Refer back to Figure 3 as you complete this table, reflecting on your own story. What pathways might you identify as you consider how you conceptualize your lived experiences. Remember that counselling is not a linear process, and there may be different points of entry for working on any one presenting concern.

C. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Conceptualizing client lived experiences: Macey’s challenges and preferences

Now complete the table drawing on what you know so far of Macey’s story, applying the concepts, principles, and practices in this chapter. What do the various versions of your responses suggest about the locus of control or responsibility for Macey’s challenge (i.e., located in the client or in the contexts of the client’s life)?

Then watch Part 9 of Macey’s story below. You may want to loop back to revisit your evolving hypotheses after you watch the video.

Then watch Part 9 of Macey’s story below. You may want to loop back to revisit your evolving hypotheses after you watch the video.

Macey’s story Part 9

Watch Part 9 of Macey’s story, attending to how you might apply the concepts, principles, and practices related to contextualizing client challenges and preferred futures.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yaskynskyy (2021, April 16)

Reflect on the elements of Macey’s story that you might want to centre in your conversation with Macey this week. Then join Gina and Sandra as they debrief this video together.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 25)

Take a moment to consider your cultural identities as they interface with Macey’s culture. How might your approach to working with Macey be influenced by your culture and social location?

APPLIED PRACTICE ACTIVITIES

A. Responsive Techniques

Preparation

For each technique you will employ a variety of microskills in a way that is responsive to the client–counsellor relationship and client-centred conversation in-the-moment. Please extend your skills practice to 14 to 15 minutes each to increase your comfort with sustaining the counselling conversation over time.

Identify a challenge with which you are currently struggling, ensuring that it offers opportunities for your partner to engage in inquiry into the sociocultural contexts of your lived experience and the dominant or nondominant discourses that may influence the challenge. If you drew on the story you have been working on through each chapter of the ebook for the applied practice activities in Chapter 8, feel free to continue to explore that challenge or whichever new challenge you introduced. Alternatively you can choose to focus on a different issue. You will use the same challenge for each of the applied practice activities below so you can build upon and deepen your contextualization of client challenges and preferences as you try out each of the techniques introduced in this chapter.

You may find it useful as a beginning counsellor to thinking about your counselling sessions in these smaller 15-minute chunks. In the early stages of counselling when you are building responsive relationships with clients, you might manage each 15-minute segment of a counselling session by asking yourself some of the following questions. You will have a chance to practise this process in the activities below.

Start-up self-reflection questions (prior to each chunk of conversation)

-

- What shared understanding of the client’s challenges has emerged in the previous session or previous chunk of conversation?

- What are my current hypotheses about the challenge and, if appropriate in-the-moment, the client’s preferred futures?

- What more can we flesh out to come to a shared, multidimensional, culturally responsive, and contextualized understanding of client challenges and preferences?

- Which technique can best support your continued co-conceptualization of the client lived experiences?

Wrap-up self-reflection questions (toward the end of this chunk of conversation)

-

- How has the use of this technique and the continued client–counsellor dialogue altered your current hypotheses about client challenges and preferences?

- How can you make transparent your hypotheses and check your perceptions with the client to support constructive collaboration in conceptualizing their challenges and preferences?

Ongoing self-reflection questions (as client challenges and preferences become clearer)

-

- How will you know when you have reached a comprehensive understanding of client challenges and preferences?

- What can indicate that you are ready to move on together to setting therapeutic directions? (Chapter 10)

Before you start into these applied practice activities, please review these relational practices from previous chapters so that you can attend to them in your feedback to each other. Some of the earlier criteria that applied to microskills more specifically have not been included.

- strengths-focused (versus challenge-focused) responses (Chapter 4)

- client-centred (versus counsellor-centred) responses (Chapter 7)

- thick (versus thin) description (Chapter 7)

- variety of microskills (Chapter 8)

- culturally responsive (versus ethnocentric) lens (Chapter 8)

- contextualized and systemic (versus decontextualized and individualist) lens (this chapter)

We provided an example through the four parts of Bennu’s story of how to move through each of the techniques in this chapter sequentially, deepening your shared understanding of the client’s contextualized challenges and preferences with each new technique. We are not suggesting you would do this with all clients or that there is anything special about this particular sequencing; instead, we want to give you an opportunity in the practice activities below to experience what it might be like to move from one technique to another.

1. Exploring Sociocultural Contexts

(45 minutes)

Preparation

If you are introducing a new challenge this week, take 3–4 minutes prior to the skills practice to provide your partner with a sense of the challenge as a starting place for them to explore sociocultural contexts with you.

In your roles as counsellors, take a moment to consider the start-up self-reflection questions (above) prior to engaging in the skills practice.

- What shared understanding of the client’s challenges has emerged in the previous session or previous chunk of conversation?

- What are my current hypotheses about the challenge and, if appropriate in-the-moment, the client’s preferred futures?

- What more can we flesh out to come to a shared, multidimensional, culturally responsive, and contextualized understanding of client challenges and preferences?

- Which technique can best support your continued co-conceptualization of the client lived experiences?

Skills practice (14–15 minutes each)

- Client: Describe the challenging you are facing, offering a hint about one of the contexts of your life that may be relevant to understanding the nature of the challenge.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on a variety of microskills to engage the client in a conversation about the ways in which the contexts of their life influence their understanding of the challenge they face.

- Client: Respond as naturally as possible to the counsellor’s use of each of the microskills they choose.

- Counsellor:

- As you near the end of your practice session, consider the Wrap-up self-reflection questions:

- How has the use of this technique and the continued client–counsellor dialogue altered your current hypotheses about client challenges and preferences?

- How can you make transparent your hypotheses and check your perceptions with the client to support constructive collaboration in conceptualizing their challenges and preferences?

- Synthesize your shared understanding of the clients challenge and the contexts in which it arises as well as any emergent hypotheses about their preferred futures.

- As you near the end of your practice session, consider the Wrap-up self-reflection questions:

Reflective practice and feedback

- How did breaking the counselling session down into chunks and applying the self-reflection questions provide meaningful structure to this part of your conversation.

- How successful were you in sharing your initial hypotheses about the client’s challenges and preferences?

- Provide each other with specific feedback on the following relational practices from earlier chapters:

2. Deconstructing sociocultural narratives

(45 minutes)

Skills practice (14–15 minutes each)

At this point, you will have a sense of some of the contextual, systemic influences on the client’s lived experiences, and you will begin to explore the messages they have received, and potentially internalized, through past and present interactions within those contexts or systems.

- Counsellor:

- Draw on whatever microskills are appropriate to move into deconstructing sociocultural narratives with the client.

- Continue to ask yourself: What more might we need to flesh out to come to a shared multidimensional, culturally responsive, and contextualized understanding of client challenges and preferences?

- Client: Respond as naturally as possible.

- Counsellor:

- As you near the end of your practice session, revisit the Wrap-up self-reflection questions:

- How has the use of this technique and the continued client–counsellor dialogue altered your current hypotheses about client challenges and preferences?

- How can you make transparent your hypotheses and check your perceptions with the client to support constructive collaboration in conceptualizing their challenges and preferences?

- Pay attention to your current understanding the locus of control or responsibility for the challenge and how this might influence preferred outcomes?

- Synthesize, noting any shifts in, your shared understanding of the client’s challenge and the contexts in which it arises as well as any emergent hypotheses about their preferred futures.

- As you near the end of your practice session, revisit the Wrap-up self-reflection questions:

Reflective practice and feedback

- How did the process of deconstructing sociocultural narratives shape your shared understanding of client challenges and preferences? What barriers did you encounter in identifying and assessing the influences of dominant or nondominant discourses?

- Provide each other with specific feedback on the relational practices:

- culturally responsive (versus ethnocentric) lens (Chapter 8)

- contextualized and systemic (versus decontextualized and individualist) lens (this chapter)

3. Reframing

(45 minutes)

Preparation

In your roles as counsellors, take a moment to reflect silently on the ongoing self-reflections questions prior to engaging in the skills practice.

- How will you know when you have reached a comprehensive understanding of client challenges and preferences?

- What might indicate that you are ready to move on together to setting therapeutic directions? (Chapter 10)

Skills practice (14–15 minutes each)

The technique of reframing can follow logically deconstructing sociocultural narratives, because it invites consideration of alternative, more health-enhancing lenses or discourses.

- Counsellor:

- You may want to practise reintroducing the current shared hypothesis about client challenges and preferred futures as if there was a pause between this conversation and the previous two activities (i.e., the client is returning for another session).

- Draw on the start-up, wrap-up, and on-going self-reflection questions to help you provide structure to the continued conversation.

- Introduce and apply the technique of reframing to flesh out more fully how the client would like things to be different.

- Toward the end of the video synthesize your current shared understanding of the client’s challenge and preferences.

Reflective practice and feedback

- How effective were the alternative lenses or discourses introduced in helping to shape your shared understanding of client preferences?

- Provide each other with specific feedback on the following relational practices as they related to the process of reframing:

4. Externalizing

(45 minutes)

Preparation

A name or cultural metaphor for the challenge may have emerged as you implemented the previous three techniques. This process of naming is part of the technique of externalizing. If nothing has emerged at this point, you may want to think ahead to potential ways to name the challenge, both as the client and as the counsellor, to facilitate your skills practice.

Skills practice (14–15 minutes each)

- Counsellor:

- Continue to draw on the start-up, wrap-up, and on-going self-reflection questions to provide structure to the continued conversation.

- Find a way to shift naturally from the endpoint of your previous conversation into the technique of externalizing.

- Toward the end of the video synthesize your current shared understanding of the client’s challenge and preferences, paying particular attention to the ways in which the client has begun to act upon the externalized challenge.

Reflective practice and feedback

- Choose 2–3 of these relational practices as your focus of feedback related to the process of externalizing:

- strengths-focused (versus challenge-focused) responses (Chapter 4)

- client-centred (versus counsellor-centred) responses (Chapter 7)

- thick (versus thin) description (Chapter 7)

- variety of microskills (Chapter 8)

- culturally responsive (versus ethnocentric) lens (Chapter 8)

- contextualized and systemic (versus decontextualized and individualist) lens (this chapter)

- Together consider the two ongoing self-reflection questions below as a lead-in to moving into setting therapeutic directions in Chapter 10.

- How will you know when you have reached a comprehensive understanding of client challenges and preferences?

- What can indicate that you are ready to move on together to setting therapeutic directions? (Chapter 10)

REFERENCES

Audet, C., & Paré, D. (Eds.) (2018). Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice. Routledge.

Brown, L. S. (2010). Feminist therapy. American Psychological Association.

Budge, S. L., & Moradi, B. (2018). Attending to gender in psychotherapy: Understanding and incorporating systems of power. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 2014–2027. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Canadian Psychological Association. (2015). CPA Policy Statement on Conversion/Reparative Therapy for Sexual Orientation. https://cpa.ca/docs/File/Position/SOGII%20Policy%20Statement%20-%20LGB%20Conversion%20Therapy%20FINALAPPROVED2015.pdf

Collins, S. (2018a). Collaborative Case Conceptualization: Applying a Contextualized, Systemic Lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 556–622). Counselling Concepts.

Collins, S. (2018b). Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide. Counselling Concepts. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/

Collins, S. (Ed.) (2018c). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts.

Collins, S. (2018d). Enhanced, interactive glossary. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 868–1086). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Dupuis-Rossi, R. (2018). Indigenous Historical Trauma: A Decolonizing Therapeutic Framework for Indigenous Counsellors Working with Indigenous Clients. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 275–304). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Dupuis-Rossi, R. (2020). Resisting the “attachment disruption” of colonisation through decolonising therapeutic praxis: Finding our way back to the Homelands Within. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 8(2). https://pacja.org.au/

Dupuis-Rossi, R., & Reynolds, V. (2019). Indigenizing and decolonizing therapeutic responses to trauma-related dissociation. In N. Arthur (Ed.), Counseling in cultural context: Identity and social justice. Springer.

Fellner, K., John, R., & Cottell, S. (2016). Counselling Indigenous peoples in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 123–147). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Freedman, J., & Combs, G. (1996). Narrative therapy: The social construction of preferred realities. W. W. Norton.

Hargons, C., Mosley, D., Falconer, J., Faloughi, R., Singh, A., Stevens-Watkins, D., & Cokley, K. (2017). Black lives matter: A call to action for counseling psychology leaders. Counseling Psychologist, 45(6), 873–901. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017733048

Jean Baker Miller Training Institute. (2017). The development of relational–cultural theory: Self-in-relation. https://www.wcwonline.org/JBMTI-Site/the-development-of-relational-cultural-theory

Jordan, J. V. (2010). Relational–cultural therapy. American Psychological Association.

Lenz, A. S. (2016). Relational–cultural theory: Fostering the growth of a paradigm through empirical research. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 415–428. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12100

Moradi, B., & Budge, S. L. (2018). Engaging in LGBQ+ affirmative psychotherapies with all clients: Defining themes and practices. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 2028–2042. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22687

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2018). A new therapy for each patient: Evidence-based relationships and responsiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889–1906. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678

Nyland, D., & Temple, A. (2018). Queer informed narrative therapy: Radical approaches to counseling with transgender persons. In C. Audet and D. Paré (Eds.), Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice (pp. 159–170). Routledge.

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage.

Ratts, M. J., & Pedersen, P. B. (2014). Preface. In M. J. Ratts & P. B. Pedersen (Eds.), Counseling for multiculturalism and social justice: Integration, theory, and application (4th ed., pp. ix–xiii). American Counseling Association.

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2015). Multicultural and social justice competencies. Association for Multicultural Counseling and Development, Division of American Counselling Association: http://www.counseling.org/docs/default-source/competencies/multicultural-and-social-justice-counseling-competencies.pdf?sfvrsn=14

Ratts, M. J., Singh, A. A., Nassar-McMillan, S., Butler, S. K., & McCullough, J. R. (2016). Multicultural and social justice counseling competencies: Guidelines for the counseling profession. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 44(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12035

Roysircar, G., Studeny, J., Rodgers, S. E., & Lee-Barber, J. S. (2018). Multicultural disparities in legal and mental health systems: Challenges and potential solutions. Journal of Counseling and Professional Psychology, 7, 34–59. http://www.thepractitionerscholar.com/index

Saleem, F. (2018). My identity as a racialized Muslim woman mental health professional. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 249–251). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Singh, A. A., & Dickey, L. M. (2017). Introduction. In A. Singh & L. M. Dickey (Eds.). Affirmative counseling and psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming clients (pp. 3–18). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14957-001

Singh, A. A., & Moss, L. (2016). Using relational-cultural theory in LGBTQQ counseling: Addressing heterosexism and enhancing relational competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 94(4), 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12098

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: Summary report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. http://nctr.ca/reports2.php

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2020, December 2). How climate change is multiplying risks for displacement. https://www.unhcr.org/news/stories/2020/12/5fc74f754/climate-change-multiplying-risks-displacement.html

White, M. (1984). Pseudo-encopresis: From avalanche to victory, from vicious to virtuous cycles. Family Systems Medicine, 2(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091651

White, M. (2007). Maps of narrative practice. W. W. Norton.

White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative means to therapeutic ends. W. W. Norton.

Worell, J., & Remer, P. (2003). Feminist perspectives in therapy: Empowering diverse women (2nd ed.). Wiley.

This acronym stands for two-spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual. The + stands for other ways individuals express their gender and sexuality that challenge binary, heteronormative, homonormative, and other culturally oppressive norms. We have chosen an ancronym that foregrounds two-spirit as an act of decolonization.

Identifies with the sex assigned at birth

Identifies with a gender that doesn’t align with that assigned to them originally

Within a male/female binary, attracted to the gender they are not