Chapter 1 Centring Relationships in Counselling Practice

by Sandra Collins, Gina Ko, Yevgen Yasynskyy, Ben Kuo, Monica Sesma, Melissa Jay, Stephanie Nardone, Brandin Glos, Mariam Mahdi, and Nada Hussein

In this first chapter, we provide an overview of some of the major influences on our positioning of counselling relationships as the central organizing construct for this ebook. We build on the brief rationale we provided in the Introduction to begin to answer the central, organizing question: In what ways can the relational practices of the counsellor and the nature of the therapeutic relationship shift, adapt, or be altered altogether in response to the specific cultural identities, contexts, values, worldviews, and needs of each individual client? It is important to point out that it is impossible for us to answer fully this question for you, precisely because of its client-centred nature. We will introduce conceptual and theoretical guidelines, invite you into a process of ongoing critical reflection about the practice of counselling, offer you an opportunity to learn new skills and techniques, and expose you to diverse voices and perspectives. However, all these elements come together only when you engage directly with each individual client, couple, family, group, or community with whom you work. It is only in the context of those lived relationships that you can come to understand more fully the nature of the relational practices that will serve clients’ unique, culturally embedded, and contextualized needs.

The creative development process of this resource was collaborative, iterative, and nonlinear. We invited feedback on our vision from students, instructors, and colleagues. That vision has also evolved over time through our own work and through the contributions of the many contributors to this ebook.

- Relational practices. In this section of each chapter, we introduce the conceptual, theoretical, and applied practice principles that support the overall goal of centring the counselling relationship in our work with all clients. Often we complement these with applied practice examples to bring the concepts and principles to life. We position these principles and practices as foundational to the rest of the content in the chapter, because they foreground client-centred and values-based practice, which is, in turn, foundational to implementing counselling processes, microskills and techniques, and reflective practice.

- Counselling processes. The ebook is also roughly organized to mirror some of the initial elements of the counselling process. We do not present these as steps, because counselling is a fluid and iterative process. However, we have tried to provide a meaningful flow over the course of the ebook, beginning with the process of welcoming clients in this chapter, moving through coming to a shared understanding of clients’ lived experiences, and finally setting directions for the therapeutic process. We do not address specific change processes in this ebook. Rather, our focus is on conceptualizing client lived experiences as a foundation from which to envision change.

- Microskills and techniques. Throughout the ebook, we also introduce a set of counselling microskills and techniques that are designed to support the relational practices and counselling processes introduced in each chapter. These are accompanied by demonstration videos of various kinds to enhance your learning.

- Reflective practice activities. It is our belief that reflective practice is foundational to responsive relationships. Reflective counsellors (a) recognize the need for self-awareness, including cultural self-awareness; (b) actively engage in critical self-reflection before, during, and after encounters with clients; (c) open themselves to feedback from clients, colleagues, and supervisors; and (d) continuously integrate that feedback to enhance their understanding of self and other.

- Applied practice activities. In most chapters we include applied practice activities that are designed (a) for self-study, if you are accessing this resource for your own professional development, and (b) for use in counselling courses at universities or colleges. These activities require a partner, so now would be a good time to think about with whom you might work to develop your proficiency in the relational practices, microskills, and techniques introduced in those chapters.

In this first chapter, we start by grounding the importance of relationships in counselling in the professional literature to give you a sense of the background for this ebook. We then introduce you to the counselling process by discussing what it means to welcome clients into a responsive, therapeutic environment. We will wait until Chapter 2 to introduce any specific microskills and techniques. To begin the process of reflective practice, we introduce you to Macey, a client whose composite story emerged from our reflections on what we have heard and learned from our own clients and our conversations with our colleagues about their work. An overview of the chapter is provided below.

Chapter 1 Overview

Recommended additional reading

Collins, S. (2018). Culturally responsive and socially just relational practices: Facilitating transformation through connection. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 441–505). Counselling Concepts.

This chapter applies the culturally-responsive and socially just counselling model to client–counsellor relationships. It introduces of some of the ideas that form the foundation for this ebook.

RELATIONAL PRACTICES

In this section, we draw on the professional literature in counselling and psychology to provide a rationale for centralizing relationships in counselling practice. We begin with an examination of the common factors research that highlights the relative influence of theoretical and transtheoretical variables on counselling outcomes. This leads logically into a discussion of values-based practice, in particular the importance of the lenses of cultural responsivity and socially justice. Finally we introduce recent research on responsive relationships that ties together and builds upon the common factors, multicultural, and social justice foundations. Our intention is to ground our assertion that relationships are central to counselling practice in the historical and emergent literature in counselling and psychology.

A. Common Factors

There is now a considerable body of evidence to support the assertion that certain common factors across theoretical approaches are more significant in accounting for therapeutic outcomes than factors specific to each approach (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015; Nuttgens et al., 2021). These common factors are often clustered into three primary areas: client factors, counsellor factors, and relationship factors (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015). Later in this chapter, we review recent research on responsive relationships, which has considerable overlap with the common factors research, particularly in terms of client factors and relationship factors (Norcross & Wampold, 2018). As we strive to build a foundation for effective and culturally responsive counselling relationships in this ebook, we will attend carefully to these transtheoretical factors.

To capitalize on client factors in this ebook, we strive to honour the uniqueness of each client, tailoring the counselling process to their cultures and worldviews, ways of being in relationship, and the specific contexts of their lives (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015; Norcross & Wampold, 2018). We also attend carefully to building an intentionally collaborative relationship (therapeutic alliance) through which clients and counsellors work together to define therapeutic directions and to envision change in line with client-centred perspectives and needs (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015; Norcross & Lambert, 2018; Nuttgens et al., 2021). Through this process clients can develop a sense of expectation for change that is often associated with positive therapeutic outcomes (Norcross & Lambert, 2018; Wampold, et al., 2017). The development of an empathic bond between counsellor and client is central to the therapeutic relationship, which we argue must be grounded in mutuality and cultural responsivity (Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Nuttgens et al., 2021; Wampold, et al., 2017).

We will also address counsellor factors. Nuttgens and colleagues (2021), in review of the literature in this area, concluded that “ ‘expertise’ is more of a dynamic concept, one that involves a focus on skill improvement, lying outside of adherence to a singular theory.” We will introduce reflective practice principles and processes to support you in ongoing skill development as well as increased intentionality in your interactions with clients. Fostering intentional practice also enhances client expectancy: their hope and belief that therapeutic processes will lead to outcomes they desire (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015; Nuttgens et al., 2021). One final common factor that is integrated throughout this ebook is client feedback (Feinstein et al., 2015; Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Nuttgens et al., 2021), which we frame in terms of practice-based evidence later in this chapter.

Notice that counselling theories are not prioritized in this summary of the factors that influence the efficacy of counselling practice. The common factors research and the current writing on responsive relationships challenges the status of counselling theory, suggesting that the specific choice of theory is significantly less critical to the counselling process. In fact, the evidence suggest that most models of counselling are equally effective when we attend to the common factors in change (Duncan, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2015; Norcross & Wampold, 2018; Nuttgens et al., 2021). We argue that what is more important is the ability to co-construct with the client a culturally responsive shared understanding of the challenges they face and a meaningful, coherent sense of direction that offers them hope and motivates their engagement in the process.

As consumers of psychological research, it is also important to apply continuously a critical lens to assess the applicability and relevance of even well-established principles and practices to BIPOC and other nondominant populations. We will invite you frequently to look at your assumptions about counselling from multiple perspectives. As we focus on the common factor of counselling relationships, in particular, we invite you to consider the ways in which client culture and context might influence what is perceived as therapeutic and growth-fostering for each individual you encounter.

Our major focus in this ebook is on the relationship between counsellor and client, which the common factors literature reinforces as foundational to the efficacy of the therapeutic process. Further, we question the influence of the other common factors if the foundation of a therapeutic relationship is lacking. Parrow et al. (2019) introduced concept of evidence-based relationship factors, as a subset of the common factors that are “distinctly relational” (p. 330), and therefore, may not be drawn upon as part of the client–counsellor relationship in all counselling models. In this sense, they are common only to certain approaches to counselling. We will attend to the eight relationship factors they identified throughout the ebook:

- Rogers (1961, 2007) original conditions of congruence or authenticity, unconditional positive regard, expression of empathy on the part of the counsellor;

- the therapist positioning of cultural humility drawing on Davis et al., 2016 and Hook et al. 2013;

- the working alliance, defined originally by Borden (1979) to include both sense of emotional connection as well as collaboration and consensus on therapeutic directions and processes;

- attention to reparation of ruptures in the client-counsellor relationship and attention to countertransference; and

- progress monitoring, which includes informal client feedback and more formalized outcomes monitoring processes.

B. Values-Based Practice

In the Introduction we positioned our thinking and writing within the constructivist paradigm, which leads us to foreground the subjective nature of knowledge, to value diversity in perspectives, and to recognize the existence of multiple realities (Gergen, 2015; Socholotiuk et al., 2016). This positioning is consistent with the emergent consensus within the professions that counselling and psychotherapy are inherently values-based practices (Collins, 2018d). We contrast this with the historical embeddedness of counselling in individualist worldviews (Audet & Paré, 2018; Collins, 2018f) that derived from a modernism or positivism paradigm. We challenge the individualist assumptions of the objectivity of the counsellor, the universality of linear views of health and healing, and the assertion that experience can be understood from a decontextualized and intrapsychic lens (Bemak & Chung, 2015; Collins, 2018f; Paré & Sutherland, 2016). Instead we invite you to recognize the ways in which you, as counsellors, are deeply embedded in the sociocultural contexts of your lived experiences, and to consider the influence of the values you hold and, therefore, those values that seep into your interactions with clients, consciously or unconsciously.

We do not believe it is possible to set aside these influences to assume a value-neutral position in counselling (Collins, 2018b). We invite you instead to examine and re-examine continuously both personal and professional values in service of your clients. In counselling, as in society as a whole, certain sociocultural narratives or cultural perspectives are given more weight than others. Dominant (i.e., individualist, colonial) discourses often have more influence on the meaning attached to various experiences, while alternate meanings are ignored, invisibilized, or inaccessible until they are brought into conscious awareness (Gergen, 2015). Values-based practice, by way of contrast, begins with personal reflection undertaken by each counsellor on the nature and source of their own deeply held values and assumptions about human nature, how problems develop, and how change occurs. It also involves individual and collective application of a critical lens to counselling theories and practices to make transparent how these may be embedded in oppressive paradigms (Ginsberg & Sinacore, 2015; Greenleaf & Williams, 2009; Mintz et al., 2009; Paré, 2013) and to look for alternative ways to approach health and healing as appropriate to each client.

I recently watched an old video, recorded early in my career, in which I talked about my theoretical orientation. I was surprised by the personal–professional values I expressed. When I watched this video again, I felt embarrassed by my naivete and the weakness of my appreciation, in that moment-in-time, of the social determinants of health and the impact of social injustices on both client lived experiences and resources for health and healing. However, it offered me a chance to be transparent about the need for continuous self-awareness and critical reflection on values.

In that video, I foregrounded self-responsibility as one of the core values that influenced my work with clients. As I reflect critically on the source of, and my attachment to, that values-based position, I see how it emerged through the combination of factors specific to my lived experiences. First, growing up in a very white, middle-class, privileged world afforded me opportunities not available to many of my clients. Second, my experiences of adolescence and early adulthood built in me a fierce independence and self-reliance, which was not actually healthy for me. Third, there were lingering influences of colonial and individualist worldviews grounded in both my social location and my earlier conservative religious upbringing. At the time of the video, self-responsibility was not a consciously and carefully selected professional value; rather it was a projection of my own journey and my assumptions about health and healing in that moment in time.

As you move into this new learning experience, I invite you to be courageous in your self-examination, while being gentle and kind with yourself as you take risks to expose and reflect critically on the values and assumptions that you hold. Take the time to examine the origins of those values as a means of loosening their grip on you. Consider alternative values that may serve you better in your role as counsellor and enhance your relational responsivity to your clients.

Sandra

This emerging consensus on the need for counsellors to engage, actively and purposefully, in values-based practice is reflected in the explicit expression of values in the codes of ethics of psychology, counselling, social work, and other helping professions (Canadian Association of Social Workers, 2005; Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association, 2020; Canadian Psychological Association, 2017). Values-based practice has also come to be strongly associated with culturally responsive and socially just counselling (Collins, 2018d), because it is often in the meeting places of diverse worldviews, lived experienced, and cultural norms that values differences emerge.

Note. We use different colours of text boxes to support your navigation through the chapter:

- Blue represents notes or tips.

- Orange is used for our own personal reflections.

- Green is for learning activities (e.g., videos, skills practice).

- Purple invites you into reflective practice on your learning.

1. Cultural Responsivity

What exactly is a responsive relationship from a cultural perspective? The term cultural responsivity has come to the foreground in the multicultural literature in the past decade with somewhat different meaning and intent than earlier terms, such as culturally inclusive, infused, diverse, or centred practice. Although the term responsivity is used in the literature in a variety of ways, Collins (2018f) positioned cultural responsivity as “a broad measure of the degree to which the counsellor and the counselling process are reflective of, and influenced by, the cultural identities, worldviews, and social locations of the client” (p. 918). The key implication of this term is the continuous integration of input and feedback from the client in the context of a collaborative counselling process (Collins, 2018d; Paré, 2013). In this ebook we focus specifically on the relational and conversational practices associated with culturally responsive counselling. Paré (2013) spoke of conversational responsivity as client-led dialogue that attends to the language, themes, and ways of knowing brought forward by the client through conversation. Paré and Sutherland (2016) defined relational responsiveness as attending to what is required at the microlevel of the conversational exchange, moment-by-moment, and with each client. We embrace this focus on immediate, moment-by-moment, responsivity to client needs, meaning, intentions, and desired outcomes. We also broaden the lens of cultural responsivity to other relational practices that foreground client worldview, views of health and healing, and social locations in our conceptualization of client lived experiences and co-creation of client-centred counselling processes (Collins, 2018a).

We have written this resource primarily as an applied practice workbook, rather than a multicultural counselling textbook. For this reason, we want to be transparent about our assumptions about our readers. In particular, we assume that counsellors or counselling students making use of this resource are familiar with some of the basic assumptions and principles of culturally responsive counselling practice.

The two quizzes below are designed to give you a sense of your current level of cultural awareness by examining your beliefs and assumptions about (a) the counselling process and (b) various nondominant populations. This is intended as a learning tool from which you are invited to create your own continued competency goals. These surveys are completely anonymous; no information is collected about you, and no tracking of IP addresses is possible. You will gain the most insight by being honest with yourself.

Click here to start Part I of the Cultural Awareness Self-Assessment (13 questions; score out of 65)

You will receive a prompt at the end of the quiz based on your overall score. The self-assessment quiz is based on the assumption that cultural awareness is a journey that will continue throughout your life and career. Depending on the prompt you receive, you may want to access additional resources to enhance your ability to benefit more fully from some of the applied practice learning in this ebook.

Note. Adapted from Culturally Responsive and Socially Just Counselling: Teaching and Learning Guide, by S. Collins, 2018. https://crsjguide.pressbooks.com/chapter/cc1/#selfassess. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Below is a list of suggested Canadian resources you might consider accessing to enhance your cultural awareness as a foundation for the learning in this ebook. The first four are specific to multicultural counselling and social justice; the others include relevant sections or chapters. These are also some of the resources that have influenced our thinking.

-

Audet, C., & Paré, D. (Eds.). (2018). Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com

-

Collins, S. (2018). Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology. Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

-

Collins, S. (2022). Culturally responsive and socially just counselling: Teaching and learning guide (2nd ed.). https://pressbooks.pub/crsjguide/

-

Kassan, A., & Moodley, R. (Eds.). (2021). Diversity and social justice in counseling, psychology, and psychotherapy. Cognella. https://titles.cognella.com/

-

Gazzola, N., Buchanan, M., Sutherland, O., & Nuttgens, S. (Eds.). (2016), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada. Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association. https://www.ccpa-accp.ca

-

Paré, D. (2013). The practice of collaborative counseling & psychotherapy: Developing skills in culturally mindful counselling. Sage. https://us.sagepub.com

-

Sinacore, A., & Ginsberg, F. (Eds.). (2015). Canadian counselling and counselling psychology in the 21st century. McGill-Queens University Press. https://www.mqup.ca

We embrace cultural responsivity in this ebook as foundational to everything we do as counsellors. It is impossible for us to isolate from our cultural selves as practitioners. It is also important to recognize that every client we encounter brings their unique cultural selves into the counselling relationship and every other aspect of the counselling process.

2. Social Justice

Our approach to responsive relationships in this ebook is also firmly grounded in a social justice lens. Collins (2018f) defined social justice by the following broad aspiration goals:

(a) fair and equitable distribution of resources, information, services, opportunities, and privileges within society; (b) full inclusion and participation of all members of society; (c) enactment of legal systems and laws that guard against discrimination and protect human rights; (d) action aimed at ameliorating past and present social injustices, cultural oppressions, and inequities across persons and peoples. (p. 1016)

One of the risks of failing to acknowledge, and engage in critical reflection on, values is that counsellors may not recognize the role of sociocultural injustices, such as systemic racism, in client health and well-being. It is our position that the call for responsivity in counselling practice applies not only to clients’ cultural identities, but also to their social locations. In other words, each client’s position of power, privilege, and opportunity (or lack thereof) within society may have considerable impact on their health and well-being. Their social location also has the potential to limit their access to appropriate mental health services. Buying into the myth that all persons and peoples have the same access to resources and supports for health and healing serves to perpetuate these social injustices (Audet & Paré, 2018; Collins, 2018g; Collins & Arthur, 2018; Sue, 2015) and may result in counselling practices that are both nonresponsive and unjust. If you are not familiar with current perspectives on social justice in counselling and psychology, you may want to review some of the resources cited in this chapter, and to access some of our suggested resources from the previous section.

As we examine the process of conceptualizing client lived experiences throughout this ebook, the lens of social justice becomes important in positioning those lived experiences in context. Applying a systemic lens includes understanding the social determinants of health, which can place certain persons and peoples at an increased health risk (Fellner et al., 2016; Ginsberg & Sinacore, 2015; McNair, 2017; Reeves & Stewart, 2015; World Health Organization, 2019). We assume a both/and approach to social justice that recognizes the importance of attending to the sociocultural contexts of clients’ lived experiences, while simultaneously engaging in justice-doing in the moment-by-moment conversations and relationships between counsellor and client (Collins, 2018d, Reynolds, 2010a; Reynolds & polanco, 2012). We will attend to, and challenge, the ways in which counselling processes themselves can reinforce or re-enact colonization and other forms of social injustice. We also will consider how social justice plays out in the values we counsellors communicate, the assumptions we make, the environments we create, the connections we build, the language we use, and the processes we engage in with clients. Collins (2018d) argued for a both/and approach that attends to what happens within as well as beyond the counselling encounter. Collins positioned social justice as a metatheoretical lens through which all aspects of the counselling process can be viewed. In this sense it becomes an ethical and metatheoretical lens (Audet, 2016; Collins 2018f; Dollarhide et al., 2016; Scheel et al., 2018; Winslade, 2018), rather than simply an outcome or destination.

Although the main focus of this ebook is on the interaction between counsellor and client(s), we believe it is important for counsellors to consider their roles in systems level change, both with and on behalf of their clients (Collins, 2018d; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016; Roysircar et al., 2018; Scheel et al., 2018). Collins (2018b) pointed to advocating for, and enacting, professional theory and practice change as one form of systems level intervention. We hope to prompt this type of systems change by re-imagining the nature of the client–counsellor relationship, foregrounding diverse perspectives on what it means to be in a healing-centred relationship, and challenging traditional language and norms related to counselling.

Throughout this ebook we will invite you into a process of applying and critiquing the metatheoretical lenses of cultural responsivity and social justice as we consider the processes of building and maintaining effective relationships with clients in service of understanding more fully their lived experiences. We begin from the assumption that all counselling is multicultural (Collins, 2018c; Paré, 2013; Paré & Sutherland, 2016; Ratts & Pedersen, 2014), in the sense that each client and each counsellor come to counselling as cultural beings embedded within multiple sociocultural contexts and systems. We will also continuously revisit the interplay of client and counsellor cultural identities (i.e., age, ability, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, social class, religious or spirituality, Indigeneity, ethnicity) and social locations (i.e., relative positions of privilege or marginalization within society) (Collins, 2018; Ratts et al., 2015, 2016).

C. Responsive Relationships

Norcross and Wampold (2018) reported on the American Psychological Association (APA) Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness in a special issue of the Journal of Clinical Psychology. The main focus of the meta-analyses and systemic reviews included in the special issue was on how to enhance treatment efficacy by adapting or responding to the uniqueness of each individual client and the contexts of their lives. The importance of responsiveness in the therapeutic relationship was foregrounded: “The goal is for an empathic therapist to collaboratively create an optimal relationship with an active client on the basis of the client’s personality, culture, and preferences” (Norcross & Wampold, 2018, A Rose section, para. 3). The task force also looked at factors specific to particular client characteristics, which will be noted in other chapters of the ebook.

2. Relationship Factors and Client Factors

Based on the extensive research of the task force, Norcross and Wampold (2018) reinforced the messaging from the common factors research and other relationship focused models of counselling (e.g., person centred, feminist, relational cultural), and concluded that “the relational ambience of psychotherapy and responsiveness to patients prove typically more powerful than the particular therapeutic method or strategy” (The Third Interdivisional section, para. 3). One of the powerful messages in this research is that counsellors and counsellor educators should devote as much, if not more time, to relationship-building and client-specific factors as they do to particular theoretical principles and change strategies. For this reason, we have devoted ourselves entirely to foregrounding relational practices in this ebook.

We also hope to supplement the ideas presented by the task force by filling in some emergent gaps. Norcross and Wampold (2018) identified “(a) elements of the therapy relationship primarily provided by the psychotherapist and (b) methods of adapting psychotherapy to patient transdiagnostic characteristics” (Conclusions section, para. 8), adapted in Figure 2 below. What this research does not provide is a road map for how to develop the specific tools with which practitioners can build responsive relationships. It is here that we pick up in this ebook with a view to supporting counsellors to build incrementally a set of competencies for engaging in client-centred, collaborative relationships that enable co-construction of shared understanding of each client’s unique and contextualized lived experiences. These competencies include guidance about how to adapt therapist ways of being and relating to specific client characteristics (Norcross & Wampold, 2018).

Figure 2

Relationship Factors and Client Factors Influencing Counselling Outcomes

| Efficacy | Relationship Factors | Client Factors |

| Effective | Alliance Collaboration Consensus on therapeutic direction Empathy Positive regard and affirmation Client feedback |

Culture (Indigeneity, ethnicity) Religion/spirituality Client preferences |

| Probably effective | Congruence/genuineness Real relationship Emotional expression Cultivating positive expectations Managing countertransference Repairing relationship ruptures |

Readiness for change Stages of change Coping style |

| Promising but requiring more research | Self-disclosure Immediacy |

Attachment style |

| Important but not yet investigated | Sexual orientation Gender identity |

Note. The language in this figure has been adapted slighted as part of our philosophical positioning. We also eliminated factors specific to change processes, which are not addressed in this ebook. Adapted from “A New Therapy for Each Patient: Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness,” by J. C. Norcross and B. E. Wampold, 2018, Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(11), 1889-1906, Conclusions. (https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22678). Copyright 2018 by John Wiley & Sons.

2. Evidence-Based Practice and Practice-Based Evidence

Through our review of the literature on common factors, values-based practice, and responsive relationships, we have provided an evidence-based practice foundation (i.e., application of knowledge emerging through psychological research) for centralizing relationships in counselling practice. However, it is important to recognize that much of the evidence we have examined also points toward the need for principles and practices for gathering practice-based evidence (i.e., direct and indirect feedback from clients) (Paré, 2013; Paré & Sutherland, 2016). Norcross and Wampold (2018) called on practitioners to engage in evidence-based relationships that are adapted or tailored to the individual client. This process of creating client-centred responsivity necessarily involves gathering feedback (practice-based evidence) from clients. We appreciate the play on words suggested by Paré (2013), “This is about response-ability, the readiness and ability to respond” (p. 131).

Applying evidence-based practice with care

In this video, Sandra invites critical reflection on the importance of balancing evidence-based practice (guidance from professional theory and research) with practice-based evidence (specific client information and feedback).

© Sandra Collins (2021, January 20)

Take a moment to generate a list of ways that you might check in with clients to see if the concepts, principles, and practices you draw upon from theory and research fit for them.

D. Therapeutic Conversations

As noted above, our primary focus in this ebook is on the counsellor and client moment-by-moment process of relating and conversing. Growth-fostering relationships and therapeutic conversations do not simply occur because the counsellor is a nice person who wants to be helpful. What distinguishes these relationships and conversations from those clients might have with a family member or a good friend is the intentional use of particular relational and linguistic tools to support client health and well-being. There is no magic to these tools. It is the critical, intentional, and collaborative use of the relational and conversational tools that is helpful to clients.

1. Relational Competencies

A large body of literature has, over the past several decades, informed relational competencies in counselling (Calvert et al., 2016; Gómez, 2020; Singh & Moss, 2016). We define relational competencies as interpersonal processes that influence the quality of the client–counsellor relationship and create space for growth to occur. What is important in this definition is that these occur at the level of the relationship and that they must be mutual. In Figure 2 for example, Norcross and Wampold (2018) identified empathy as a relational factor that has demonstrated efficacy in supporting counselling outcomes. However empathic I might feel toward a client, that empathy does not become a relational practice until it is expressed in a way that is meaningful and accessible to the client and in response to their specific needs in-the-moment.

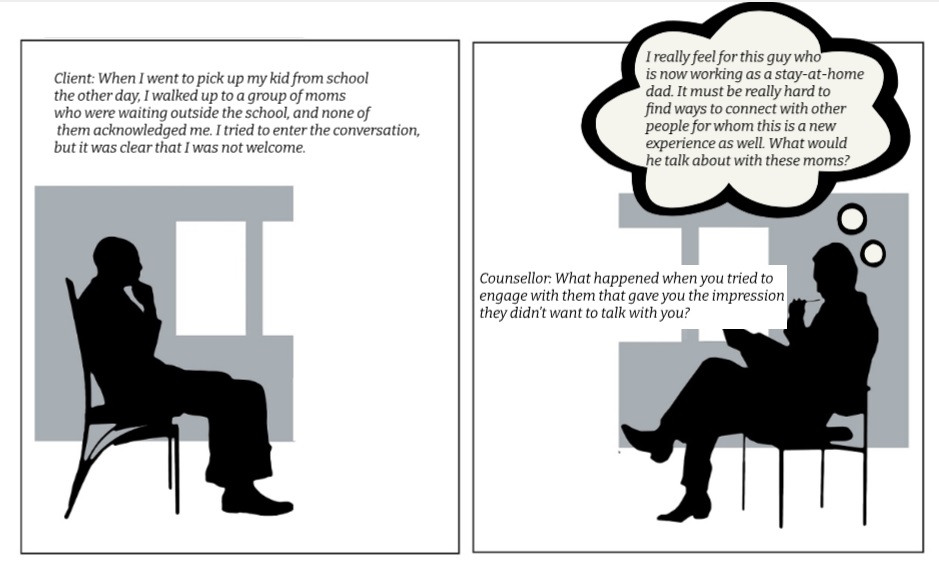

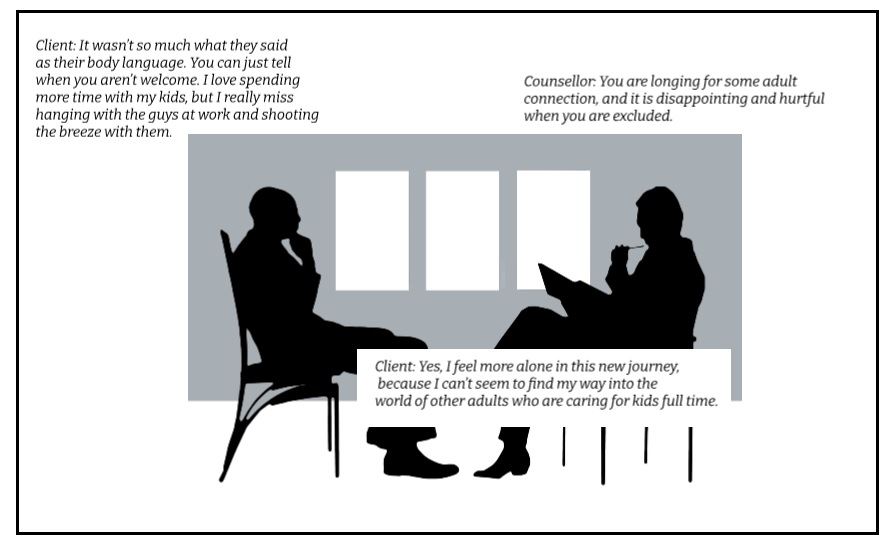

Consider the following exchange between counsellor and client.

The counsellor’s question may be appropriate if the purpose is to gather information; however, the counsellor’s empathic response remains invisible to the client.

The client has now received the intended expression of empathy in a way that is meaningful to them. The counsellor response has opened the door to consider possibilities for connection with other stay-at-home parents. Empathy has moved from a personal, internal response to an interpersonal, relational practice.

This transcript provides access to this content in pdf format.

Throughout the ebook, we will introduce a series of relational practices, connecting these to various points in the counselling process in which they may be particularly useful.

2. Just Conversations

The term just conversations has come to be associated with the assertion that social justice plays out in counselling in the moment-by-moment, utterance-by-utterance interaction between counsellor and client. What the counsellor says and how they say it becomes critical to ensuring the counselling process is responsive to the cultural experiences and contexts of clients’ lives (Audet & Paré, 2018; Collins, 2018d; Paré, 2013; Wulff & St. George, 2018). Audet and Paré (2018) asserted that, within the helping professions, certain discourses are privileged, which then influence how counsellors perceive clients and the stories that become available to clients to express their identities and lived experiences. Consider the following examples:

- Labelling a client, directly or in case notes, as dissociative, for example, sometimes happens without fully considering with them the meaning they associate with times they are not fully present. This practice puts a box around their experience that may be limiting or oppressive.

- Asking a client who presents as female what their husband does for a living may foreclose on client stories about their lived experiences as a queer person.

- Using the language of goal setting without collaborative conversation about worldview, might leave a client, who does not embrace the linear, eurocentric perspective on time, struggling to make meaning of the conversation.

- Engaging in “psychobabble” without checking to see what meaning clients make of the language to which counsellors are accustomed may be experienced as power-over positioning or simply inaccessible by clients.

We revisit the importance of justice in language throughout this ebook. We encourage critical reflection on the potential meanings associated with the use of particular language and advocate for tailoring language to each individual client to ensure both shared meaning-making. Examining words or phrases as meaning-laden metaphors for emotions, values, assumptions, beliefs, relationships, or experiences is a powerful tool for justice-doing (Paré, 2013) in counselling and for advancing the therapeutic process with all clients (Wagener, 2017).

As we worked together to develop this resource, we invested considerable time reflecting on language use in counselling practice, piecing it apart from its eurocentric roots. We invited colleagues to talk with us about the culturally embedded nature of counselling practices. Through these reflections and conversations, we made deliberate choices about how we describe the nature of counselling, relational practices, counselling processes, microskills and techniques. We will note our reflections and choices as they emerge in our writing.

We invite you into this process of critical engagement with language choices. As you encounter terminology for counselling concepts, practice, and processes throughout this ebook, consider the following questions:

- What resonates with you personally and professionally?

- What language use is not a fit, and how would you alter this?

- How do various terms we use function metaphorically as way makers, for ourselves as practitioners and for our clients?

- How might we hold only tentatively to language and invite client feedback to support culturally responsive and socially just conversations?

3. Structures of Communication, Microskills, and Techniques

Both relational practices and just conversation are supported through the use of specific linguistic practices. Throughout this ebook, we move back and forth between attending to (a) the nature of the therapeutic relationship and the relational practices that support it and (b) the moment-by-moment conversations between counsellor and client, which involve particular linguistic practices. If you browse through most counselling skills or theory texts, you will notice that the term, skills, is used for a wide range of counsellor behaviours. This can make it challenging to talk about skills in a meaningful and transparent way. So, we have created a nomenclature that we hope will simplify things for you.

- Structures of communication form the first level of skill addressed in this ebook. You will recognize these as the basic linguistic patterns you use in your day-to-day communications. Such patterns take the form of (a) questions (i.e., how, what, where, when, why?), (b) statements, (c) minimal encouragers (ah, hmm), and (d) nonverbal behaviours.

- Counselling microskills are particular forms of questions or statements that serve a specific function within the counsellor–client dialogue. They are typically single sentences with a particular structure and purpose. For example, What is the most meaningful learning for you in this chapter? demonstrates the microskill of questioning.

- Counselling techniques are intentional linguistic practices that draw on one or more counselling microskills. These techniques often involve a short sequence of exchanges between counsellor and client for a particular purpose. For example, the counsellor might ask a question, provide some specific information, ask another question, and reflect back to the client what they understood from the conversational exchange.

The counselling microskills and techniques that are presented in this ebook are reflective of a collaborative and co-constructive relational stance (Collins, 2018; Paré, 2013), rather than a particular theoretical model. Their appropriateness with each client is determined moment-by-moment on the basis of client needs, preferences, cultural identities, and contexts, as well as the focus of the counselling process in-the-moment.

However, it would be misleading to suggest that there are no theoretical underpinnings associated with the concepts, principles, and practices we foreground in this ebook. We have drawn microskills and techniques from various counselling models, which we will make transparent as we introduce each one. However, as authors, we espouse a metatheoretical perspective that is positioned within the postmodern and constructivist paradigms. It will be important to attend to this metatheoretical lens as you move through this ebook, because it undergirds many of the concepts and practices we discuss and the ways in which we approach their use in counselling.

The intent of this chapter is to provide a conceptual overview of the principles that underpin the approach we have taken to centralizing relationships in this ebook. In Chapter 2, we begin to introduce specific microskills and techniques to support these relational goals.

COUNSELLING PROCESSES

In each chapter, we focus on particular elements of the counselling process, beginning here with welcoming clients. We deliberately use active verbs to emphasize the ongoing and iterative nature of many of these processes. By way of contrast, nouns such as initial intake are more static.

A. Welcoming Clients

The process of welcoming clients continues through the next few chapters as we talk about concepts such as hospitality and safety, for example. In this section, we focus initially on the welcoming processes that occur before you encounter clients for the first time (e.g., addressing stigma, engaging with social media), and then we focus on creating conversational practices that minimize language barriers.

1. Acknowledging the Stigma of Counselling

In 2021, both the academic and practitioner communities agree that stigma is a legitimate barrier for individuals attempting to access counselling and other mental health services. Clients often report experiencing self-stigma, the internalization of negative stereotypes and beliefs (Stangl et al., 2019). Although counselling has become a relatively common practice within health services in North America, it is important to recognize that many cultural groups around the world address mental health concerns through family, community, and cultural healers (Saleem & Martin, 2018). It may be a completely foreign concept to some clients to share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences with a counsellor or other healthcare practitioner. The result is a significant stigma associated with counselling services as well as pressure from family and community not to go to counselling (Qasqas, 2018; Saleem & Martin, 2018). This stigma may be strengthened by experiences of marginalization or discrimination when potential clients attempt to access services (Qasqas 2018; Nyland & Temple, 2018). For members of other nondominant communities (e.g., BIPOC, 2SLGBTQIA+, working-class), the stigma of mental health services may derive more directly from mistrust and fear based on negative, and sometimes traumatic, experiences within the healthcare system (Dupuis-Rossi, 2018; Lavell, 2018; Nyland & Temple, 2018). The result is that systemic barriers are erected to the accessibility and responsivity of counselling services, and counsellors must work to overcome these.

The continued stigma attached to mental health (World Health Organization, n.d.) is especially prominent in nondominant, racialized, and ethnic populations. Self-stigma and perceived stigma by others hinder racialized groups such as Black, Asian, and Latino individuals from seeking counselling (Cheng et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2017). In the text box below, Gina speaks specifically about her counselling experiences with Asian clients. Many more reached out to her during the pandemic, because they were experiencing anti-Asian racism, and because she speaks Cantonese, which provided a language and cultural bridge.

I find myself impressed when an Asian client reaches out for counselling services, because there are words in Cantonese that equate to being absolutely crazy (chee seen) if someone talks to a psychologist. Interestingly, this idea of chee seen is not the same when someone sees a medical doctor. My Asian clients may experience shame, fear, confusion; some ponder, “What would people say if they know I see a counsellor or psychologist; they would think I’m crazy.” For these reasons, utilization of mental health services is not common in the Asian community (Wu et al., 2017).

In my practice, I validate these messages and commend clients for taking the step to heal, gather ideas, and thrive. I often speak my client’s first language, Cantonese, especially when they are 50 years or older; many of them came to Canada as refugees from Vietnam in the late 70s and early 80s, and some immigrated from China or Hong Kong in the 80s and 90s. I also see clients who are young professionals. They do not need the language bridge. Instead, they reach out to me, because they think I will “get” the intergenerational gap, the ways that Chinese families fight, the high expectations and pressures from parents, and more.

Some of my Asian clients express relief that they reached out for counselling and wish their friends and family members would come see me. They value the experience of being heard and learning new tools, and they feel like a weight has been lifted. They wonder why they did not choose to access counselling earlier in life.

These anecdotal messages are encouraging in this time when Chinese people and people who look Asian are being targeted by racism, xenophobia, and violence. The origins of coronavirus in China tapped a strong historical thread of anti-Asian racism that was fueled by actions of the former American president (e.g., labelling it the Chinese virus). Canada has a very dark history of systemic racism towards members of the Asian communities that bubbles up in times of stress when people feel threatened or afraid. I have seen this play out in my personal life. My family members have been called, “Hey Corona” by their friends. People think it is funny to do so, but it isn’t. Labels like this are a form of othering and dehumanizing an entire racialized group.

In this increasingly racially charged environment, I am moved and touched when Asian clients muster up courage to combat the stigma of accessing psychological services. I worry for those who do not reach out because of internal cultural stigma and external systemic racism during a time when they may need professional support the most.

Gina

Self-reflection

Think about a time when you met someone who impressed and moved you. What was that experience like? What qualities and life experience drew you into conversation to learn more about them? What would it be like to apply that experience in your counselling practice? How might this relational positioning foster a strengths-based, culturally curious approach to each client you encounter?

2. Communicating Responsivity

In this first chapter our focus is on welcoming clients into the counselling process. However this process of welcoming can begin long before the client and counsellor actually meet. It is important to consider the information that clients may access about you and your practice both online and in other ways that might influence whether they choose to make a connection with you in the first place. How are you communicating responsively to them as cultural beings, located in particular social contexts, with unique perspectives and needs?

Optimizing Social Media Presence

In the 21st century, there is little to no chance of escaping the internet and social media in our daily lives. Many counsellors share information and opinions on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and on other social media platforms. There is such an abundance of social media platforms that it is easy to lose track of our digital footprint. As a result, it is possible for our personal and professional lives to become blurred and intertwined. It is important to create personal–professional boundaries that enable therapists to hold a professional media presence, while privatizing other accounts by limiting access to only family and friends (Raypole, 2020).

Although regulatory bodies have yet to develop clear guidelines related to social media presence, there are ethical risks to therapists becoming “friends” with clients on social media. Clients may post content in their own accounts that they do not intend for therapists to see, and they may not process this risk when they initiate or agree to connecting (Lannin & Scott, 2014; Raypole, 2020). Feng (2020) suggested that therapists not respond to clients who land on their Instagram or other social media pages; if Feng does respond, they do not acknowledge their client–therapist relationship and treat the encounter similarly to bumping into a client in public. We strongly encourage you to think critically about this issue and to develop an explicit social media policy, one which you might discuss with clients as a foundation for being clear about professional boundaries (Lannin, & Scott, 2014; Raypole, 2020).

In the video below, Dr. Marie Feng, a psychologist in private practice, provides some suggestions for what to include in your social media policy.

© Private Practice Skills (2020, January 24)

If you want to see the samples Dr. Feng talks about in this video, please view this video in YouTube.

Counselling professionals must be careful about how they present themselves to the public, whether in an online or a face-to-face context. Remember, anyone can search the Internet and social media, making it crucial to be mindful of what you post. Many public figures have been criticized for posting or reposting opinions, jokes, or other comments on social networks. In some cases, this has resulted in public backlash and shunning. This is an example of cancel culture, a “the practice or tendency of engaging in mass canceling as a way of expressing disapproval and exerting social pressure” (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

Let’s apply a critical lens to the following true story.

While on her flight in 2013, Justine Sacco, a senior director of corporate communications, tweeted, “Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDSs. Just kidding. I’m white!” (Ronson, 2015). Once Sacco landed in Africa, those words became the most trended tweet on Twitter. She was fired immediately and lost her reputation, colleagues, and friends (Ronson, 2015).

Although this is a dramatic example, there can be similar ripple effects from more subtle examples of poor judgement or cultural insensitivity in social media posts. Imagine this happening in your life. The result could be irreparable damage, lost income, and a tainted reputation. It may place you in an unrecoverable position relative to your professional goals. We invite you to be careful and mindful of your social media presence, especially since it is now such a significant part of our daily lives. Consider the following questions for reflection:

- Jokes are often used a way to “soften” unsavoury beliefs and assumptions. Whether or not the joke is an accurate reflection of your values and beliefs, what impact might sharing it have for you, personally and professionally?

- If you are a member of a IBPOC community, how would you feel about this example of a “joke”? How would this affect your sense of cultural safety? What implications would it have for engaging with this person?

- What is communicated through social media can become a permanent record, even though people grow and change. What attitudes or perspectives from your past might you not want foregrounded as you move into your career as a professional counsellor?

My social media presence: Let’s do an audit

Types and Examples of Social Media Platforms

|

Types |

Examples |

| Social Networking | Facebook, LinkedIn, Google+ |

| Social and Micro Blogging | Twitter, Blogger, Tumbler |

| Photo Sharing | Instagram, Pinterest, Flickr |

| Video Sharing | YouTube, Vimeo, TikTok |

| Consumer Review Networks | Yelp, TripAdvisor, Amazon, IMDB |

Perform an audit on your social media platforms and your digital presence on the Internet.

- Complete a Google search for your name and/or company.

- Are there accounts you forgot about that appear in the search?

- Do you want them to remain active or should you take steps to inactivate them?

- Scan the social networks you most often use.

- Do you have public and private accounts? Are these clearly separated?

- Are there posts, comments, or other materials you would rather not have clients see?

- Create a plan to remove or hide any irrelevant or outdated information.

- Ensure that all of your profile information that is accessible to the public is up to date.

Providing Culturally Sensitive Space

Because of the stigma associated with counselling, direct experiences of discrimination and marginalization, and the lack of accessible and culturally responsive services, clients from marginalized communities may carry with them a sense of distrust and fear even once they make the choice to engage in counselling (Nyland & Temple, 2018). Once you have ensured that your Internet and social media presence communicates your values of inclusivity and responsivity to a diverse range of clients, it is important to turn your attention towards the physical space in which your services are provided.

Physical accessibility is an important starting place for ensuring enabling environments (Whitehead, 2015); this includes both accessible and gender-neutral washroom facilities. Collins (2018f) stressed the importance of attending to the messages communicated through choices of art and other decor, magazines and other print materials available in the waiting room, and other cultural symbols in your office environment that can include or exclude clients. An important survival strategy for some members of marginalized communities is vigilance about their physical environment, which may make them more immediately aware of subtle cues that suggest a potential lack of safety, invisibility, or marginalization. The process of cultural auditing (Collins et al., 2010; Collins, 2018e) involves focused and purposeful reflection on all aspects of professional practice. It is an important first step in welcoming clients into a culturally responsive and socially just counselling experience.

Preparing the Virtual Space: Teletherapy

At the time we were writing this, the world was, and perhaps still is, in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, and most graduate programs in Canada being delivered online using remote, synchronous or asynchronous learning. Concurrently, many counsellors and psychotherapists have transitioned their practice to teletherapy (Burgoyne & Cohn, 2020) to ensure social distancing and decrease further outbreaks, whether or not this is their preferred medium for working with clients (MacMullin et al., 2020). Some studies have found that digital mental health services can be just as effective as in-person therapy; they also offer convenience and the ability to reach people in more remote areas (Rutherford, 2020).

In my private practice, I transitioned to add teletherapy over a period of one week at the start of the pandemic lockdown in 2020.

- I developed a telepsychological services consent form, drawing on the APA (2020) checklist.

- I paid attention to cyber security, ensured that the video platform I use is Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA) compliant.

- I asked for clients’ emergency contact information, in case the technology failed, and I needed to contact them in another way.

- I encouraged them to find a private (enough) space in their homes or workplaces for our conversations.

- I also created my own space at home and developed a routine of preparing to “see” clients in that space. It is crucial to have a private space that communicates professionalism.

- I made sure there were no distractions, so I could be fully present.

- I dressed in a professional way, but did not overdress.

I am learning to be more comfortable with technology as the pandemic continues (MacMullin et al., 2020). This preparation is important, because life and work become blurred (Burgoyne & Cohn, 2020). During the first lockdown, when my family was home, I let them know when I was stepping into work. If they needed me, they would need to wait (unless there were an emergency). I shut my office door, which is really an area in my room on the third floor. I used a trifold to cover half the room so that clients saw only the bookshelf to the right of me.

I have used both phone and video counselling, and I am now quite comfortable with both modes. However, like many mental health professionals, I am aware that I have a bias for in-person counselling (Perrin et al., 2020). This bias comes from my own experience meeting with my counsellors in their offices. I love that we are in a physical room together and are processing my challenges in a space that makes nonverbal communication easy to decipher. One drawback to teletherapy is that nonverbals can be difficult to interpret. In video, there may be lag time, and my client and I may unintentionally cut each other off or talk over each other. On the phone, I find I am attending more closely to the client’s tone of voice or speed of speech. I interrupt gently to ask a question, if the client is talking continuously.

Gina

We will talk about Zoom fatigue (Fosslien & Duffy, 2020) in Chapter 11. However, please begin to apply some preventative self-care strategies that you have already developed as you engage in this virtual learning process. Create a routine to break up your times of intense focus as you would between clients. Take breaks for movement, meals, and self-care. Online learning and telehealth services are likely to continue to evolve into more commonplace experiences, in part because of the increased accessibility to services and resources they offer. It is important to adapt and to be open to diverse ways of offering counselling services to serve a wide range of clients. However, as healthcare professionals, you are expected to follow the guidelines available through the professional literature and regulatory bodies to ensure client confidentiality and safety.

Tips for optimizing communication through video technology

- Connect your device directly to your modem if possible, or ensure sufficient wireless signal strength.

- Use a secure home or work device; do not access videoconferencing software from a public computer.

- Place your device on a hard surface (i.e., a desk or table, not your lap or couch).

- Check your lighting to ensure there is a clear image of you and your facial expressions.

- Sit directly in front of, and facing, the camera.

- Turn off other electronic devices or sounds to minimize disruptions (e.g., cell phones, notifications).

- Ensure your privacy to speak freely, maintain confidentiality, and minimize distractions.

- Use a head set to enhance sound quality for you and your clients. This also ensures that others at home or work cannot hear your conversations.

- Prepare, in advance, all comfort items (e.g., tissues, beverages).

3. Challenging Counselling Conventions

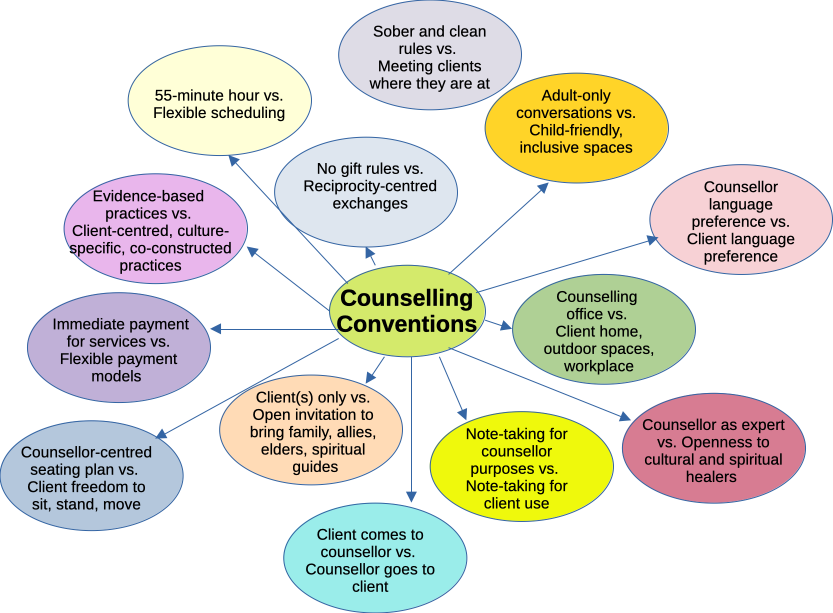

The term counselling conventions is used to describe the norms that have evolved within counselling practice in North America that determine the when (i.e., scheduling, length of session, frequency of contact, nature of endings), where (i.e., office setting, physical or virtual space), who (i.e., client, family members, support persons, interpreters), and what (i.e., activities, practices) that define, and sometime confine, engagement with clients. Many of these are embedded in eurocentric worldviews that themselves are embedded in classist, ableist, patriarchal systems (Collins, 2018c; Fellner et al., 2016; Lavell, 2019; Robertson et al., 2015). These may not fit well with the needs, cultural values, social locations, or contexts of clients’ lived experiences.

Adapting to Client Needs

One of the core principles foundational to this ebook is client-centred practice, which we reinforce through the conceptual framework provided in this chapter. Tailoring counselling to the specific needs, preferences, identities, contexts, and lived experiences of each client (Norcross & Wampold, 2018) necessarily involves critical reflection on counselling conventions. We invite you to consider how the when, where, who, and what of counselling might be adapted to optimize accessibility, responsiveness, and efficacy of counselling services. In Figure 3 we offer a few ideas about normative counselling conventions that may need to be up-ended or at least transformed responsively depending on the particular clients you work with and the contexts of their lived experiences.

Figure 3

Common Counselling Conventions

Standards for professional boundaries and norms have emerged to support ethically responsible practice, to which it is important to attend. However, these many of these standards evolved in colonial and eurowestern contexts without critical consideration of diversity. We encourage you to consider critically what it might be like to support responsive, client-centred norms, rather than inflexible, institutionalized norms. What does safe-enough space look like for you? How might the limitations of your comfort zone influence your responsivity to clients? What tensions might arise in challenging counselling conventions? How might you ethically and responsively manage those tensions?

Standards for professional boundaries and norms have emerged to support ethically responsible practice, to which it is important to attend. However, these many of these standards evolved in colonial and eurowestern contexts without critical consideration of diversity. We encourage you to consider critically what it might be like to support responsive, client-centred norms, rather than inflexible, institutionalized norms. What does safe-enough space look like for you? How might the limitations of your comfort zone influence your responsivity to clients? What tensions might arise in challenging counselling conventions? How might you ethically and responsively manage those tensions?

Honouring First-Language

Language is intimately connected to culture. It is an important way in which cultural meanings are shared, and it can be difficult to communicate certain meanings without the original words or phrases in which they emerged (Boutakidis et al., 2011; Ko, 2014; Willis-O’Connor et al., 2016). Incorporating linguistic and cultural factors in counselling is culturally responsive when there is a mismatch of language between the client and counsellor (Kuo, 2018; Rodriguez-Keyes & Piepenbring, 2017; Seto & Forth, 2020). This includes inviting clients to use their first language, embracing language switching when clients feel more comfortable using their first language for self-expression, and using interpreters when needed (Kuo, 2018; Rodriguez-Keyes & Piepenbring, 2017; Seto & Forth, 2020). In the videos below, we invite colleagues who work with clients who face language barriers in accessing counselling services to speak to their experiences and to provide some guidance about how you might honour first language in your counselling practice.

Therapeutic use of language interpreters

Contributed by Ben Kuo, Stephanie Nardone, Brandin Glos, Mariam Mahdi, and Nada Hussein

In this video Ben Kuo describes how to effectively integrate language interpreters into the therapeutic process. Stephanie, Brandin, Mahdi, and Nada bring the principles to life through a series of role-plays of therapist–interpreter–client interactions.

© Ben Kuo (2021, April 27)

Questions and prompts for reflection

- Consider the implications of working through a language interpreter for our theme of creating a welcoming space in this chapter. What specific conversational principles stood out for you from this video?

- Which of these principles might apply well to working with all clients to ensure effective and responsive communication and relationship-building?

- We focus attention throughout this ebook on the language we use, both in talking about and talking with clients. Reflect honestly on what might influence your tendency to use of complex or colloquial language with clients. How might you begin to develop the habit of speaking more clearly about counselling concepts, principles, and practices?

Contributed by Monica Sesma (interviewed by Gina Ko)

In this video Monica Sesma and Gina Ko talk about honouring clients’ first languages in counselling. They share their experiences of working in their first languages with clients.

© Monica Sesma & Gina Ko (2020, November 22)

Consider the following questions for reflection:

- If you are a person who speaks multiple languages, how might you take advantage of offering the gift of first language communication to your clients? Looping back to earlier conversations about welcoming clients before you encounter them, how might you communicate this service to clients through your social media presence.

- If you are required to engage in counselling predominantly in a language that is not your first language, how might you mitigate the exhaustion and strain that can arise from constant communication with clients and colleagues in your second, third, or fourth language? What supports might you need to put in place for self-care?

- If you are a monolingual individual, how might you honour client’s first language if it differs from your own? What might you do to communicate openness to finding ways to minimize the impact of linguistic barriers for your clients?

In Canadian regions and systems in which English (or French) is the dominant language, systemic language bias often emerges. Both non-English counsellors and clients can run up against this form of cultural oppression. What might it look like to challenge the assumption that English should dominate counselling services in favour of acknowledging the limitations of monolingual environments in effectively servicing clients? Take a few moments to reflect critically on where the root of the problem really lies. As you prepare to welcome all clients into your counselling practice, what might you do to mitigate potential language biases you may hold?

REFLECTIVE PRACTICE

One of the main ways that counsellors and other healthcare practitioners continue to grow and enhance their professional competencies is through reflective practice (Scheel et al., 2018). Counsellor critical reflexivity involves attending in-the-moment, and in retrospect, to all aspects of interactions with clients, which requires increasing self-awareness of your thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Collins, 2018c). Central to reflective practice is self-assessment and enhanced self-awareness of the ways in which your values, assumptions, beliefs, and other dimensions of cultural worldviews and social locations enter into the therapeutic relationship, either consciously or unconsciously (Collins, 2018c; Coulson & Homewood, 2016; Scheel et al., 2018). In addition to reflective activities interspersed throughout each chapter, we have devoted a section specifically to reflective practice to encourage active engagement in this core element of your learning process.

1. Preparing Yourself

In this chapter we have been focused on welcoming clients into your counselling practice; however, in this section on reflective practice, we shift our attention to how to prepare yourself to engage in responsive, culturally sensitive, therapeutic conversations with clients. It is important to consider how you bring yourself into these relationships, which may start with attending to your relationship with yourself. We are privileged to integrate, throughout this resource, a series of videos from Melissa Jay, who carries forward the important theme of self-care, beginning with the video below.

Preparing ourselves to connect with clients

Contributed by Melissa Jay

In the video below, Melissa Jay reflects on how to prepare both yourself and your physical environment to create an inclusive and accessible space. She introduces the importance of centralizing commitment to yourself as a foundation for meeting with clients.

© Melissa Jay (2021, February 18)

Consider the following questions for reflection:

- What might it mean for you to position self-care as an ethical obligation to yourself, your clients, and your profession?

- What is one small step you can take this week to increase your care for yourself as a foundation for caring for others?

2. Enlisting Your Own Story

We invite you to begin your journey of self-reflection by identifying a challenge you are currently facing in your own life. You will be prompted to reflect on this challenge as you move through each chapter of the ebook. We hope that by enlisting your own story in service of your professional development, you will engage in another layer of self-reflection on your learning.

Choose an issue that is not easily resolved, but is also not deeply emotional or traumatic. Picture yourself preparing to seek out counselling for the challenge you have identified. Revisit the overview for this chapter in Figure 1, and reflect on the following questions. Take notes, create a mind map, make use of sticky tabs, or otherwise begin to organize your thoughts in some meaningful way.

- Visualize yourself taking preliminary steps to access counselling services. Where would you go? What first impressions would influence your choices? What red flags would you look for?

- Which of the common factors resonate for you? Which of these have supported your growth or healing in other relationships or previous counselling experiences?

- What values would you look for in a counsellor? Why are these values important to you? How do these desired values relate to your lived experience as a cultural being, located within specific family, work or school, community, organizational, or broader sociocultural contexts?

- What type of client–counsellor relationship would feel responsive to your preferences, identities, and social locations? What evidence might you look for to ensure your needs would be met?

- How open are you to discussing your challenges with a counsellor? What might hesitancy, fear, or shame tell you about your assumptions and beliefs about the practice of counselling or helping professionals? Where are those barriers rooted for you?

- How important would it be to work with a counsellor who shared your first language? If you are a multilingual person, what would enhance your ability to express yourself freely and to ensure shared understanding?

Take a few moments now to begin to create your story, then:

- Note what is most significant and meaningful to you.

- Draw on images, memories, pieces of literature, or photographs to capture your lived experience.

- Think about how you might begin to share your story with another human being.

Self-reflection and self-care

If you choose to walk with us down the path of self-reflection, particularly as it pertains to a specific challenge in your life, please plan ahead for support systems if you need them. Pair up with a colleague or peer, talk to a trusted friend or family member, or check out counselling services in your local area. If the process of self-reflection evokes distressing emotions or thoughts, please draw on these resources to support your health and healing.

3. Engaging with Macey’s Story

Next we offer you the beginnings of the story of Macey that will carry forward into subsequent chapters. This story was created from composites of various clients we have encountered throughout our careers as well as our own lived experiences, both personal and professional. The purpose of following the story across chapters is to give you another way to engage in reflective practice. Please position yourself in the role of counsellor. We encourage you to use the story as a springboard for your own ongoing reflection and competency development. If you are using this ebook as part of a course, your instructor may choose to use this story as a starting place for class conversations.

Introducing Macey

In this first video, we introduce the kind of information you might receive as you start into your work with a new client. As you watch the video, attend to assumptions you make about Macey and to the questions and curiosities that emerge for you.

© Gina Ko & Yevgen Yasynskyy (2021, April 7)

Imagine yourself in the role of counsellor preparing to meet with Macey for the first time. Reflect on the content of Chapter 1, as you consider the following questions.

- What information from Macey’s intake form might you consider further with her?

- How might you better understand Macey’s hopes and expectations for the counselling process?

- Macey noted the desire to work with a counsellor who was culturally responsive. What more would you want to know about Macey’s perspective and needs?

- How might attention to first language play out, based on the language(s) you each speak?

- Macey has shared examples of the challenges she is facing and the cultural resources on which she draws. What would you attend to in Macey’s story and where you might initiate further conversation with her?

In the video below Gina and Sandra share some of their reflections on Macey’s story, which may add to the ideas you have generated for yourself.

© Gina Ko & Sandra Collins (2023, May 25)

REFERENCES

American Psychological Association. (2020). Office and technology checklist for telepsychology services. https://www.apa.org/practice/programs/dmhi/research-information/telepsychology-services-checklist.pdf

Audet, C. (2016). Social justice and advocacy in a Canadian context. In N. Gazzola, M. Buchanan, O. Sutherland, & S. Nuttgens (Eds.), Handbook of counselling and psychotherapy in Canada (pp. 95–122). Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association.

Audet, C., & Paré, D. (2018). Preface. In C. Audet and D. Paré (Eds.), Social justice and counseling: Discourses in practice (pp. xviii–xx). Routledge.

Bemak, R., & Chung, R. C. (2015). Critical issues in international group counseling. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 40(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01933922.2014.992507

Boutakidis, I. P., Chao, R. K., & Rodríguez, J. L. (2011). The role of adolescents’ native language fluency on quality of communication and respect for parents in Chinese and Korean immigrant families. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 2(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023606

Burgoyne, N., & Cohn, A. S., (2020). Lessons from the transition to relational teletherapy during COVID-19. Family Process, 59(3), 974–988. https://doi.org/doi:10.1111/famp.12589

Calvert, F. L., Crowe, T. P., & Grenyer, B. F. S. (2016). Dialogical reflexivity in supervision: An experiential learning process for enhancing reflective and relational competencies. Clinical Supervisor, 35(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/07325223.2015.1135840

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). Code of ethics. https://casw-acts.ca/en/what-social-work/casw-code-ethics/code-ethics

Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association. (2020). Code of ethics. https://www.ccpa-accp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CCPA-2020-Code-of-Ethics-E-Book-EN.pdf

Canadian Psychological Association. (2017). Canadian code of ethics for psychologists (4th ed.). Retrieved from http://www.cpa.ca/docs/File/Ethics/CPA_Code_2017_4thEd.pdf.

Carrol, L. (1982). Alice’s adventures in wonderland and through the looking-glass: And what Alice found there. Oxford University Press.

Cheng, H.-L., Kwan, K. -L. K., & Sevig, T. (2013). Racial and ethnic minority college students’ stigma associated with seeking psychological help: Examining psychocultural correlates. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 98–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031169

Collins, S. (2018a). Collaborative case conceptualization: Applying a contextualized, systemic lens. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 556–622). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/

Collins, S. (2018b). Culturally responsive and socially just change processes: Implementing and evaluating micro, meso, and macrolevel interventions. In S. Collins (Ed.), Embracing cultural responsivity and social justice: Re-shaping professional identity in counselling psychology (pp. 689–770). Counselling Concepts. https://counsellingconcepts.ca/