4 Late Adulthood: 70 and Above

Jay Seitz

But who pretends that life is one slowly ascending curve of human development? Most of the time you have to smash into something: the death, the broken relationship, the horrible career moment. Then you think, Well, what matters to me? What do I enjoy? Or even just, I’m still here.

– Kenneth Branagh (British actor and filmmaker, NYTimes, 11.01.2021)

TABLE OF CONTENTS (TOC)

- Chronic disease of aging that shorten lifespan

- Why do we age?

- Aging and longevity

- Neurodegenerative diseases and disorders

- Aging and work

- Employment vs. retirement

- Cognition and memory

- Keeping the mind active versus cognitive decline

- Intelligence, creativity, and wisdom

- Behavioral health

- Sociality in later life

- Well-being and emotion

Chronic Diseases of Aging that Shorten Lifespan

PowerPoint Presentation: Chronic Diseases of Aging that Shorten Lifespan

Why do we age?

In 1957 George Williams (1926-2010, evolutionary biologist) proposed a major theory of aging. It’s called antagonistic pleiotropy.

In a nutshell, antagonistic pleiotropy is when one gene controls for more than one trait (pleiotropy), where at least one of those traits is beneficial to the organism’s fitness early in life and at least one is detrimental to the organism’s fitness later in life due to a decline in the force of natural selection. If you remember from biology class, natural selection is one of the driving forces of evolutionary change.

For example, if a gene caused both increased reproduction in early life and aging in later life, then senescence (senility; getting older) would be adaptive in evolution. Thus, follicular depletion in human females—depletion of eggs in the female’s ovaries and loss of follicular activity—causes both regular menstrual cycles early in life and loss of fertility later in life, known as menopause. Thus it was selected for in human evolution by having its early benefits outweigh its late costs.

So genes select for reproductive and fitness advantages early in life but are “antagonistic” to development in later life and bring on cell senescence, which we experience as aging.

So, aging is essentially “programmed” into the organism.

But that’s not the whole story. Development across the lifespan actually plays a large part in all this.

A hallmark of organismal aging–humans, in our case–is the proliferation of growth-promoting pathways from childhood and adolescence into middle age that are no longer useful and have become hyperfunctional, that is, over-productive and increasingly useless.

Or to put it another way, as we age cell division throughout the body and brain slows down. Growth-promoting pathways from our childhood and adolescence, however, continue throughout the body and brain converting these now non-proliferating cells to a senescence state, a process called “geroconversion.” But, as a result, these cells are rendered hypertrophic (enlarged) and hyperfunctional (continue to operate but with no clear purpose). This is known as the hyperfunction theory of aging.

It turns out that there are ways to inhibit geroconversion and extend human and animal “healthspan”–as well as lifespan–by turning off major aging pathways in the body. But that is for discussion at another time.

What are some of the negative effects of this geroconversion? Cancer is a big one but in the next section we will look at other deleterious effects of aging.

Aging and Longevity

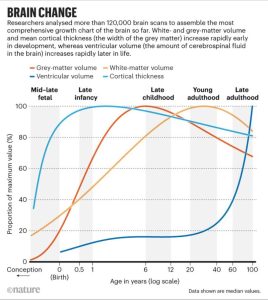

If we look at brain changes over the lifespan, notice what’s decreasing from adolescence (see diagram below): Grey matter volume, cortical thickness, cerebral volume, and the surface area of the cortex, all of which have to do with thinking, problem-solving, and memory. From adolescence on, the brain is literally shrinking.

White matter connections begin to decrease in middle-age, which connect all of those areas for thinking and memory to each other and are responsible for humans’ incredibly diverse intelligences, abilities, and skills.

Brain Changes Across the Lifespan

Neurodevelopmental Disorders: Faulty Programming Early in Life

PowerPoint Presentation: Neurodevelopmental Disorders and Disease

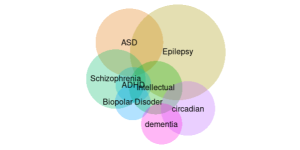

Neurodevelopmental disorders (see diagram below) like autism (ASD), problems with attention (ADHD), anxiety (ANX) and mood disorders (MDD/BD), and schizophrenia (SCZ) are rampant in early life except for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s (AD) as well as other forms of dementia, which tend to begin to rear their ugly head in middle age.

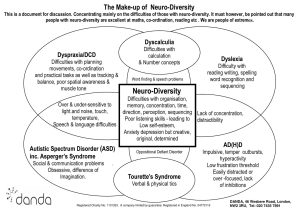

Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Why these disorders of development in childhood and adolescence? Well, for one thing, your “genome”–the 23 pairs of chromosomes that are the blueprint of your future–can be misprogrammed from the start (no blueprint is perfect) and the programming of these genes can easily go astray during development due to both internal programming errors (there are up to 50,000 genes on these 23 chromosome pairs with over 3.1 billion base pairs of DNA) as well as extensive external insults from the environment during development such as childhood abuse; exposure to alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs; childhood diseases; neurotoxicants such as lead and arsenic, and so on. Lots can go wrong.

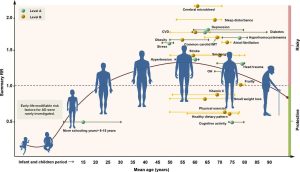

Moreover, modern humans are “wired” for a quick ascent and a slow decline (see diagram below). As a result, aging is now thought of as a disease resulting in a potpourri of chronic diseases and disorders of aging like diabetes, hypertension, obesity, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, cataracts, macular degeneration, benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), cardiovascular disease, cancer, and dementia including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. New treatments to delay aging and increase healthspan, however, are on the horizon. And sooner than you might think.

Healthspan

Neurodegenerative and Neurocognitive Diseases and Disorders

PowerPoint Presentation: Neurodegenerative Disorders and Diseases

PowerPoint Presentation: Neurocognitive Disorders

The standard model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)–the most common neurodegenerative disease–postulates that the production of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide (peptides are short chains of amino acids that form proteins), stimulates the development of tau neurofibrillary tangles (tau is a protein composed of larger chains of amino acids that stabilize axons interacting with neighboring neurons) as well as inflammation in the brain or “neuroinflammation.” Thus, Aβ, tau, and neuroinflammation have been proposed to lead to the destruction of neurons and synapses in the adult brain in AD.

A new theory, however, suggests that infections of both the brain and body triggers the immune system in the brain and that sets off neuroinflammation.

What kind of infections? Microbes that attack the brain, known as neurotropic microbes include the family of herpes viruses including herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) and 2 (HSV-2), which cause cold sores and genital herpes, respectively. In the US, about half of adolescents and adults under the age of 50 are infected with HSV-1 and about 12% are infected with HSV-2. As it turns out, antivirals such as acyclovir reduce the accumulation of both Aβ and tau in the brain.

But there are other neurotropic microbes linked to AD including the varicella-zoster virus (VZV) implicated in chickenpox and shingles and widespread in the US population. There is also the hepatitis C virus implicated in liver disease, Helicobacter pylori associated with gastric ulcers, Porphyromonas gingivalis, a bacterium associated with periodontal disease, Chlamydia pneumoniae, a bacterium linked to pneumonia, as well as various fungal infections.

Moreover, there are actually two immune systems in humans. The innate immune system and the adaptive or acquired immune system. When pathogens invade the brain and body, the innate system initiates inflammation, which attempts to eliminate cell injury, clear necrotic cells and damaged tissues from the body, and initiate tissue reparation. We find this system, of course, in young infants.

But as we age, the acquired immune system kicks in as the immune system learns about the specifics of new pathogens and develops defenses against them, such as lymphocytes that produce antibodies. However, chronic inflammation caused by the acquired immune system can lead to a bevy of diseases of aging including atherosclerosis, osteoarthritis, periodontal disease leading to gum recession and tooth loss, as well as disorders of the brain itself (see diagram below).

Neurodegenerative Diseases and Disorders

Key:

- FRDA – Friedreich’s ataxia is a genetic, progressive, neurodegenerative movement disorder.

- HD – Huntington’s disease is a hyperkinetic movement disorder.

- FTD – Frontotemporal disorder is a dementia of the frontal and temporal lobes. Bruce Willis, the actor, was recently diagnosed with FTD, originally thought to be Wernicke’s or semantic aphasia (i.e., inability to understand language).

- ALS – Amyothropic lateral sclerosis involves progressive loss of motor neurons that control the voluntary musculature.

- AD – Alzheimer’s disease’s early symptoms include problems with memory for events known as “episodic memory.”

- PD – Parkinson’s disease includes tremor, bradykinesia (slow movements), muscle rigidity, and problems in initiating movement.

Nootropics and Promnestics

Promnestic Drugs

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors

There is slow degradation of acetylcholine in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. So, the idea is to target cholinergic neuronal pathways that project from the basal forebrain (just in front of hypothalamus, i.e., nucleus basalis of Meynert) to the cerebral cortex and hippocampus.

Mesocortical dopamine pathways play significant role in cognitive function including verbal fluency, serial learning, vigilance for executive functioning, sustaining and focusing attention, prioritizing behavior, and modulating behavior based on social cues.

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BuChE) inactivate acetylcholine (ACh) at cholinergic synapses (AChE) and nearby glia (BuChE). Hence, acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

1. Reminyl (2001) – Galantamine hydrochloride

2. Exelon (2000) – Rivastigimine tartrate

3. Aricept (1996) – Donepezil hydrochloride – fewest side effects and first line treatment

4. Cognex (1993) – Tacrine hydrochloride

Neurocognitive disorders (NCD) are a class of brain disorders that impact mental health by primarily affecting cognition—thinking and memory—and related cognitive abilities such as language, learning, and attention.

They are acquired disorders and hence are not classed under neurodevelopmental disorders and disease, which emerge in infancy and childhood and include disorders such as autistic spectrum disorders, learning disorders like dyslexia, and intellectual disabilities such as Down’s syndrome.

Neurocognitive disorders include delirium—disturbances in consciousness, attention, and cognition—as well as the minor and major forms of NCD known as the dementias.

Mild cognitive impairment (MCI)—now listed as mild neurocognitive disorder in DSM-5—results in diminished cognitive abilities that are not expected for an individual’s education or age but do not interfere with activities of daily living (ADLs). They may occur as a transitional stage before evolving into dementia, a major form of NCD.

There is also a large class of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease that have differential impacts on cognition. Neurodegenerative disorders are, however, chronic diseases of aging whereas neurocognitive disorders are strictly disorders of cognition regardless of age effects.

In DSM-5, neurocognitive disorders are grouped into six major categories including complex attention, executive functions, learning and memory, language, social cognition, complex attention, and perceptual-motor functions.

(1) “Complex attention” includes selective, divided, and sustained attention as well as processing speed.

(2) “Executive functions” include working memory, decision-making, planning, feedback/error correction, inhibition/overriding habits, and cognitive/mental flexibility (ability to shift between concepts, tasks or rules).

(3) “Learning and memory” includes immediate memory (“working memory”), recent memory (including free and cued recall and recognition memory), very long-term memory (including semantic and autobiographical memory), and implicit learning (the learning of complex information in an incidental manner, without awareness of what has been learned; basically, procedural or skill learning).

(4) “Language” includes expressive language (naming, word finding, fluency, grammar/syntax) and receptive language.

Confrontational naming

Fluency (semantic/phonemic)

(5) “Perceptual-motor functions” includes visual perception, visuomotor construction, perceptual motor, praxis, and gnosis (perceptual integrity of awareness such as recognition of colors or faces).

(6) “Social cognition” includes theory of mind and recognition of emotions.

Delirium is disturbance in attention encompassing a reduced ability to direct, focus, sustain or shift attention and thus is a disturbance in awareness. Additional disturbances in cognition may include memory deficits, disorientation, as well as language, visuospatial, and perceptual deficits.

Delirium may result from direct physiological consequences from underlying medical conditions as well as substance intoxication or withdrawal (alcohol, cannabis, phencyclidine, inhalant, sedative, amphetamine, cocaine, opioids, and hallucinogens).

The essential feature of delirium is a disturbance of attention or awareness that is accompanied by a change in baseline cognition that cannot be explained by any preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder. Nonetheless, delirium often occurs in the context of underlying neurocognitive disorder.

Major Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD)

NCDs may be due to Alzheimer’s disease, vascular issues, Lewy bodies, Parkinson’s disease, frontotemporal issues, traumatic brain injury, HIV infection, substance or medication-induced disorders, Huntington’s disease, prion disease, or other medical conditions or from multiple etiologies.

Primary clinical deficit is cognitive function.

Significant cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains including complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual-motor or social cognition. Moreover, the cognitive deficits interfere with independence in daily living.

The impairments should be documented by standardized neuropsychological testing or other quantified clinical assessment. There are both major and minor diagnoses of all these:

Alzheimer’s disease

a. Decline in memory and learning and at least one other cognitive domain

b. Steady progressive, gradual decline in cognition

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration

a. Behavioral inhibition

b. Apathy/inertia

c. Loss of empathy

d. Perseverative, stereotyped or compulsive/ritualistic behavior

e. Hyperorality, dietary changes

f. In one variant, prominent decline in language ability

g. Genetic mutation

h. Extensive frontal and/or temporal involvement (neuroimaging)

Lewy body disease

a. Fluctuating cognition with variations in attention/alertness

b. Recurrent visual hallucinations

c. Spontaneous features of Parkinsonism

d. REM sleep behavior disorder (repeated arousal during sleep with vocalization and complex motor behaviors; cause significant distress

e. Severe neuroleptic sensitivity

Vascular disease

a. Temporally related to one or more cerebrovascular events

b. Decline in complex attention, processing speed, and frontal-executive function

c. Significant parenchymal injury due to cerebrovascular disease on neuroimaging

Traumatic brain injury

a. Loss of consciousness

b. Posttraumatic amnesia

c. Disorientation and confusion

d. Neurological signs (seizures, visual field cuts, anosmia, hemiparesis)

Substance/medication use

a. Symptoms persist beyond the duration of intoxication and withdrawal

b. Alcohol, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, inhalants

HIV infection

a. Not explained by secondary brain diseases (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy or cryptococcal meningitis)

Prion disease: Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs) that comprise a group of progressive, incurable, and fatal conditions that are associated with prions (misfolded proteins) that affect the brain and nervous system of animals including humans, cattle, and sheep.

a. Insidious onset and rapid progression of impairment

b. There are motor features such as myoclonus, ataxia or biomarker evidence

Parkinson’s disease

a. Insidious onset and rapid progression of impairment

Huntington’s disease

a. Insidious onset and rapid progression of impairment

Aging and Work

Exposure to an enriched environment, such as work, has a very positive effect on the structural and functional integrity of the brain as well as increasing healthspan. An enriched environment enhances social interaction, learning, and increased physical activity as well as pumping up neurogenesis in the late-age adult brain.

Adult neurogenesis is more prominent early in life in three regions of the brain: the adult subventricular zone where neurons are produced, the amygdala or the seat of our emotional life–particularly fear and anxiety–and the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus where memories are initially encoded. But adult neurogenesis occurs throughout the brain.

Employment vs. Retirement

Given the foregoing (above), what are the advantages of formal retirement from work versus employment?

Well, for one thing, living next to a golf course with access to a pool, hiking trails in nature, and a fitness and wellness center, may be as important, if not more so, than continuing working in an occupational role after 50 years. That depends on the individual’s view of their job and the life satisfaction it provides over a more “retirement mode.” However, many individuals continue working in some capacity as well as enjoying more extended vacation time or other leisurely activities or moving to a different part of their country or world.

Cognition and Memory

In the “Brain Change” diagram (above) we saw that there is shrinking of many areas of the brain with age and this is an inevitable process. Along with these biological changes to the brain there is mild cognitive and mnemonic (memory) decline with age. But neurodegenerative diseases and disorders can bring on more serious problems.

Neuropsychological testing, for example, in late-age adults can reveal mild cognitive difficulties up to eight years before a person fulfills the clinical criteria for diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia. These early symptoms can affect the most complex activities of daily living. Indeed, the most noticeable deficit is short term memory loss, which shows up as difficulty in remembering recently learned facts and inability to acquire new information.

Yet, Alzheimer’s disease does not affect all memory capacities equally. Older memories of the person’s life events (episodic memory), facts learned (semantic memory), and implicit memory (memory how to do things) are affected to a lesser degree than new facts or memories.

Language problems, however, are mainly characterized by a shrinking vocabulary and decreased word fluency leading to a general impoverishment of oral and written language.

Keeping the Mind Active versus Cognitive Decline

There is a distinction in psychology and neuroscience between brain and cognitive reserve. Brain reserve or the resilience of the brain to cope with increasing functional decline with age while appearing to preserve cognition and memory is a major factor in healthspan (living healthier longer) in late-age adulthood.

On the other hand, cognitive reserve is the ability to optimize brain performance through use of alternative cognitive strategies. Factors like lifestyle, education, and occupational involvement appear to be proxies for cognitive reserve and correlate positively with preservation of cognition and memory as one ages.

What kind of factors abet cognitive and brain resilience? Diet is one important factor and the Mediterranean as well as the MIND diet (a variant of the former) delay aging and tend to inhibit functional decline in both brain and body as reported in a January 2022 study in Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). A related study in JAMA also found that regular physical exercise promoted cognitive and brain resilience and delayed aging. But high social engagement and involvement in intellectice activities also staved off neurodegenerative diseases and disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

Intelligence, Creativity, and Wisdom

Both Robert Sternberg (Cornell) and Howard Gardner (Harvard) have put forth important theories about the nature of human intellect. Sternberg argues that it revolves around specific mental components in the mind, the context in which it is used, and prior experience. Gardner, on the other hand, suggests that it is not one thing, but many things, and has put forth a theory of “multiple intelligences” that have a brain, cognitive, and bodily basis and exist in humans the world over.

Exercise of these mental components or skills and their use in various contexts, along with the experience that evolves with daily use, is integral to intellective abilities. On the other hand, it’s now “how smart you are, but how you are smart that counts.” Intelligence is not one thing, but many things. And each individual has an intellective profile of varying abilities.

Yet, in spite of all the above, an essential core of human intellect is the ability to recognize and create similarities from the seemingly outward appearance of things. This is known as metaphorical or supramodular thought or the ability to think of one thing in terms of another. And it might just be the kernel of creative thought.

And then there is wisdom. One theory of wisdom attributed to Robert J. Sternberg–known as the “balance theory of wisdom”–combines features of one’s intelligence, knowledge, creativity, and common sense, yet mediated by ethical values oriented to the common good of society.

When citizens and leaders fail in the pursuit of their duties, it is more likely to be for lack of wisdom than for lack of analytical intelligence. In particular, failed citizens and leaders are likely to be foolish—to show unrealistic optimism, egocentrism, false omniscience, false omnipotence, false invulnerability, and ethical disengagement in their thinking and decision making. In other words, they fail not for a lack of conventional intelligence, but rather for a lack of wisdom.

- R. J. Sternberg (2010)

So, wisdom in late-age adults, to the extent that it exists in a particular individual, may be a result of melding one’s intelligence, creativity, and tacit knowledge learned from the interactions of daily experience to an ethical orientation of improving life for oneself and others and the good of society.

Behavioral Health

Besides physical health, behavioral health is very important in late adulthood. But what exactly is behavioral health? Well, for one thing, it is a feeling of well-being that circumscribes our psychological and social life and impacts how we perceive and cognize the world as well as our actions on it. For instance, how do we handle psychosocial stress, make decisions, and manage our relationships with others?

But it also involves our sense of autonomy or ability to do things for ourselves, our sense of competence about our own abilities, as well as our self-judgment of our own intellective, creative, and socioemotional potential.

An evolving field in psychology, known as positive psychology, emphasizes the importance of positive emotions such as confidence, hope, and trust; the importance of strengths and virtues such as courage, perspective, integrity, equity, and loyalty; and the importance of positive institutions such as democracy, strong families, free inquiry, and a free press. To be sure, happiness and psychological well-being are the desired outcomes of positive psychology.

Relieving the states that make life miserable [i.e., mental illness] has made building the states that make life worth living less of a priority. But people want more than just to correct their weaknesses. They want lives imbued with meaning, and not just to fidget until they die…. [Indeed], there is not a shred of evidence that strength and virtue are derived from negative motivation [i.e., running away from fear].

- M. E. P. Seligman, 2002

Indeed, recent studies of happiness in the US, based on a sample of over 3,000 adults, revealed that people are mildly happy only about 54% of the time (6.92 on a Likert Scale from 1 – 10; the higher the score, the greater the happiness) and neutral (5.0 on the scale) about 25% of the time. So, on average, Americans are mildly happy or neutral almost 80% of the time.

Even so, the importance of the positive emotions cannot be understated. Positive moods promote social harmony and we are more tolerant, more creative, and more forthcoming with others as well as more likely to be open to new experiences and unconventional ideas.

So, what does affects happiness? Neither wealth nor income, physical beauty, nor even objective physical health is strongly correlated with happiness. But these do:

- Marriage has very positive effects on human happiness.

- The avoidance of negative events and negative emotions has a mild effect on human happiness.

- Living in a wealthy democracy has a very positive effect on human happiness.

- A rich social network has a very positive effect on human happiness.

- Religion has a moderate positive effect on human happiness.

- More materialistic individuals tend to be less happy.

- Subjective health, not objective health, matters more to human happiness.

Sociality in Later Life

There are a number of theories of the trajectory of social life in late adulthood. One theory, the continuity theory, posits that connections with others tends to follow paths laid out in young adulthood. That is, continuity with relationships and activities from earlier in life.

A variant of this is that the investment in social networks constricts late life circumstances and choices, known as the socioemotional selectivity theory. For instance, choices tend to favor more amiable relationships and the circumstances have changed because of death of family and friends and the loss of those who have moved away.

Well-Being and Emotion

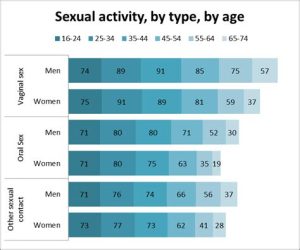

It may be not surprising to hear that late-age adults are quite sexually active even into their seventies and eighties. Relationships are very central in people’s lives and no less so in late adulthood (see chart).

Aging and Sexuality

Friends, Siblings, Marriage, and Same-Sex Partnerships

The Harvard Longitudinal Study of Adult Development studied Harvard undergraduates as well as a white male inner-city cohort from the Boston community from 1938 on and is still ongoing. It has closely tracked the lives of over 700 men and, in many cases, their spouses.

The study has found that the strength and quality of relationships with spouses, family, and friends was far more important to aging well than career success or wealth and it was a significant barometer of long-term health and well-being: Harvard Longitudinal Study of Adult Development.

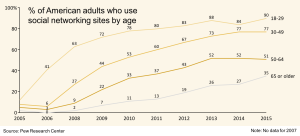

Likewise, while personal computers (Apple, Microsoft) came on the scene in the late 1970s, social media interaction does tend to vary by age with late-age adults being less engaged on social media (see graph below).

Social Media by Age

Nonetheless, late-age adults appear more engaged in direct daily interpersonal relations within their immediate social networks, which bodes well for long-term health and longevity.

[The Internet is] a technique of subordination…a device to degrade & control people. To create wants, to impose a philosophy of futility, to focus…attention on…superficial aspects of life, and to…keep [us] from the dangerous activity of interacting with one another.

– Noam Chomsky