15

Key Concept

Rebuttal Argument: argues against an existing argument; seeks to poke holes in or dismantle another argument; can offer a counterargument to the original, but doesn’t have to.

As we know, arguments don’t exist in a vacuum, and discourse is highly based on context. When we make an argument, we’re often doing so in response to other things that have been said and done. For example, an arguer rarely forwards their positions on things like gun laws or the importance of mental health initiatives without being prompted; however, when a national tragedy–like a devastating school shooting–occurs, then it compels stakeholders who are concerned about these issues or those who are directly impacted by them to articulate their views and to share those views with a wider audience.

In rhetoric, the initial event that has created the opportunity for stakeholders to offer their views on certain issues is called a kairos, which means “an opening.” The idea is that the event (the kairos) has created an opening for those who are impacted by or concerned about something to voice their positions.

However, as we all know, rarely if ever does one person voice a position without that position being critiqued or questioned by others. In fact, more often than not, when one stakeholder voices a position, another stakeholder will critique or challenge their ideas.

And that is exactly what a rebuttal argument is: an argument that argues against an existing claim.

Or, here’s another way to think about rebuttal arguments: imagine a group of three friends are driving home from the movies. One by one, everyone begins discussing the movie, and the friends all gradually learn that they all had differing opinions on it. Their conversation might look like this:

- Friend #1: “That movie was so awesome! I loved everything about it. The acting was so great; the movie was perfectly cast, and the chase scene at the end was so intense!”

- Friend #2: “Yeah, I dunno. I thought it was pretty good. I was really into the acting, for sure.”

- Friend #3: “I agree, the acting was really good, but the special effects were super weak in my opinion–so weak, in fact, that I had a hard time getting past how bad they were. It really took me out of the film in a bad way. All I could think about was how silly the special effects were.”

Notice in the above interaction, the fact that all three friends just saw the same movie presents a kairos (an opening, or opportunity) for them to discuss it and forward their opinions about it. Equally, after Friend #1 voices their stance (they really liked the movie) and their rationale for that stance (the acting and cast were good, and specific scenes were particularly riveting), Friends #2 and #3 respond to–and offer a rebuttal to–Friend #1’s stance by critiquing certain elements of the film and, thereby, Friend #1’s stance.

One final thing to note in the above interaction is that while Friends #2 and #3 critique or pick apart Friend #1’s argument that the film is good, they can still find common ground in appreciating the acting, so while a rebuttal reacts to and picks apart an existing argument, it doesn’t have to completely shut that argument down. In fact, some of the most effective rebuttal arguments seek to acknowledge the partial value of the argument they’re critiquing. This is called making a concession, when we identify the value of an opponent’s stance in the pursuit of forwarding our own position. Doing this allows us to build our credibility with our audience by helping them see that we are capable of rationally considering what someone who we disagree with is saying.

For our purposes, however, here is how we can think about making rebuttal arguments:

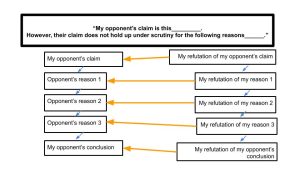

Rebuttal arguments involve refutation (identifying where the argument is wrong, flawed, or not complete) and/or offer counter arguments (offering argumentative points that differ from the original argument). To make a rebuttal argument, choose one of your text/sources you have found on your issue for the rebuttal argument. This will be your primary text, and you’ll seek to represent that argument fully and fairly so that you can refute it. Then, you must use your other sources to support your rebuttal claims that are picking apart the argument from your primary text. Remember, the goal of a rebuttal argument is to dismiss or weaken an argument so that it become irrelevant or questionable to an audience who might be or has been persuaded to accept it.

Recapping the main ideas behind rebuttal arguments:

● Rebuttal arguments argue that another argument doesn’t hold up under scrutiny

● Rebuttal arguments pick apart and critique an existing argument

● In order to preserve their own credibility, rebuttal arguments should fully and fairly represent the positions of the argument they’re critiquing

● In all arguments, but especially so in rebuttal arguments, concessions (acknowledging the value of an opponent’s position) can be really useful for building our credibility by helping our audience see that we’re capable of rationally considering conflicting stances