Frelét de Villiers; Helga Hambrock; and Ellen Rusman

Conducting an international research study may have been an idea of many researchers in the field of educational technology as the environment lends itself to international collaboration. Ideas and visions of researchers in this field may have been discussed from many angels, but the execution of an actual study is rarely attained. Walt Disney, the well-known innovator, said: “The way to get started is to quit talking and begin doing” (Newmark, 2007. p. 18). This quote became relevant to a group of researchers who are members of the International Association of Mobile learning. The researchers from five different countries in five different continents decided to “stop talking” in 2018 and became involved in a global research project that was conducted in 2019 and is now being published in this book.

Many topics were mentioned for the research study and after several brainstorming sessions during the mLearn, 17th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning in Chicago, November 2018, the ‘seamless learning’ topic crystalized as the most relevant. A bot called CONNIE (Connecting of New Neurons in Exploration) was designed for this exercise and was used as an objective content selector. It was also decided to build the research project on the study of Rusman, Tan and Firssova (2018). The study had been selected as best conference paper at the same conference, based on the innovative Disney Method that was followed for the data collection.

The researchers were selected as representatives of their countries based on their interest and positive contribution to the International Association for Mobile Learning over the years and their interest to participate. They committed to contribute to the research project by conducting the research, analyzing the data and by writing a chapter about the findings in their specific country for the proposed book.

The first steps were to set up a project plan with goals, timelines and to decide which specific theme the study would pursue. The postulated overarching statement for the study was formulated as: Seamless’ (learning) experiences should become a standard component within the curriculum of our institution.

Ensuring that meeting times would be suitable for all was a huge challenge because of the many different time zones, but all participants tried their best to be in the meetings.

In order to place the term seamless learning in a global context, a literature review on the evolution of the term is presented next. More information about what seamless learning means and how it has evolved over the years is found in each chapter with specific reference to research in the context of each country.

Historical Panorama

Looking at the concept of seamless learning, it already has quite a history in the broader international educational domain. In his overview ‘a brief history of seamless learning’ Wong (2015) sketches two main streams in literature that at first largely existed ‘apart’ and from 2011 on gradually merged conceptually. One origin, in the early 1990’s, derived from the desire in higher education to diminish the gap between in-and-out of class learning and to integrate distinct roles faculty and student affairs staff had in supporting students. From this increased staff awareness and holistic perspective on supporting students’ lives, students themselves were also encouraged to take advantage of learning resources inside and outside the classroom and to use their own life experiences to make meaning of material introduced in classes (Kuh, 1996, p. 136). Merging formal and informal learning approaches and looking at ‘the whole’ student (mind, body, spirit, talents, experience, and knowledge) and (curriculum and organizational) support as enablers characterized this perspective on ‘seamless learning’. As Wong (2015, p. 2) indicated “technological support of learning played no significant role in this discussion”.

On the contrary, the second origin sketched by Wong (2015), at the start of the 21st century, was characterized by a “greater focus on technological innovation to enable specific personalized learning activities across spaces” (Wong, 2015, p. 3). Especially scientists active in the field of mobile and ubiquitous learning reframed the ‘seamless learning’ concept within the Technology-enhanced learning domain. In an international synthesis of Chan et al. (2006, p. 23) seamless learning was described as “marked by continuity of the learning experience across different scenarios or contexts, and emerging from the availability of one [technological] device or more per student.” They stressed that the availability of personal devices could enable students to learn when they are curious in any context and to connect these different (formal and informal; individual and social) contexts in which they are learning, also through the extension of social spaces in which learners interact. Also Wong (2012, p. 22) states that a “Seamless learner should be able to explore, identify and seize boundless latent opportunities that his daily living spaces may offer to him mediated by technology…”

Reflecting on the overall history of seamless learning, one could also argue that a third early 1990’s origin can be distinguished, one that originated from the field of science learning. Here the wish to engage students in learning activities and environments that promote both ‘hands-on’ experimentation and ‘minds-on’ reflection was behind the idea to bridge the gap between formal and informal science learning (Hofstein & Rosenfeld, 1996). Although the terms ‘continuity’ and ‘seamless’ were not yet coined, Hofstein and Rosenfeld (1996, p. 106) described the blending of formal and informal learning experiences in school science in order to provide science education tailored to the needs and abilities of a heterogeneous population of citizens (‘science for all’). This stream could be considered the start of more recent research in the field of mobile and seamless (collaborative) inquiry-based learning (Burden & Kearney, 2016; Suarez, 2017; Suarez et al., 2018; Kali et al., 2018) and citizen science (Herodotou et al., 2018).

Since then, the concept of ‘seamless learning’ has been used in various manners and with various connotations. For example, to describe an envisioned ‘continuous and (cross-) contextual’ learning and support process, to mark out a design paradigm within the larger domain of learning and instructional design, to typify the organizational change of interweaving formal and non-formal learning, to describe a specific type of learning environment, to label specific and concrete learning scenarios and to describe how mobile and ubiquitous technology can influence and change the way we learn. Looking at these different connotations, Wong (2015) suggested that the definition by Sharples et al. (2012, p. 24) could be considered as the most common denominator between them, namely “seamless learning is when a person experiences a continuity of learning, and consciously bridges the multifaceted learning efforts, across a combination of locations, times, technologies or social settings.” The promise of this ‘continuity’ lies in potential learning gains, such as an increase in retention, transfer, support for the acquisition of (complex) skills, increased academic performance and motivation, awareness and change in perception(s), an increase sense of self-efficacy, next to potential organizational gains (e.g. increased efficiency and time-spend-on-learning).

Although the definition above expresses an intent and characteristics of a specific type of envisioned learning process of an individual, it does not yet express how this ‘continuity’ comes into being and whether individuals should take care of this themselves or whether they are supported in their efforts through a learner designers’ work or through supportive actors (e.g. teacher, coach). As in this chapter we specifically are looking at how the concept of seamless learning can be relevant for lifelong learning and higher (distance) education institutes, who are (formally) responsible for providing learners with the most optimal learning experiences, we here adopt a definition from a designers’ perspective. Seamless learning is therefore defined as a learning design paradigm with the intention to “Connect (learning) experiences and learning activities, through technology-supported learning scenarios using ubiquitous technology and handheld devices, that learners experience through participation in various contexts (e.g. formal/non-formal) and hereby supporting, improving and enhancing learning (and support) processes, so that learners experience a continuity of learning across environments and settings at different times and are, for their learning processes, optimally benefiting from their personal experiences both in and across contexts (Rusman, 2019, adapted from Sharples et al., 2012, p. 24)”.

Although Chan et al. (2006, p. 23) indicated that the concept of seamless learning would influence nature, process and outcomes of learning, this influence still remains modest and highly variable when looking internationally and at different educational sectors. In their systematic international scoping review study Durak & Cancaya (2018) show an increase in the number of studies on seamless learning and indicate that the importance of the concept seems to be gradually increasing. However, their detailed analysis of 58 selected articles, also shows additional issues in the field. For example, looking at where studies took place, the majority of studies (42%) were carried out in Asia (Singapore and China), mostly (almost 95% in total) amongst students and teachers at a K12 or undergraduate level. In these contexts, the concept of seamless learning is more generally applied in the domains of ‘language learning’ and ‘(inquiry-based) science education’ and to support self-regulation and reflection processes. If we look in the current daily international practices of higher (distance) education and lifelong learning, the major impact predicted by Chan et al. still remains forthcoming. Not many studies took place in higher (distance) education (yet), although this could be expected, as specifically there is a history of online academic education. Also higher vocational education could be considered underrepresented, despite the ample opportunities for ‘boundary crossing’ that are present through the combination of formal learning and ‘learning on the job’. Currently, learning environments and settings a learner moves through still remain separated in many ways (Wong & Looi, 2011). The creation of connections and the construction of an overarching context between different learning experiences and environments, e.g. in-and-outside formal learning environments, is predominantly not facilitated yet.

In the next section the research methodology that was applied during the global research project is explained and presented in more detail.

Research Methodology

The research methodology used for this global research project follows a mixed method approach – specifically a convergent parallel design. According to Merriam and Tisdell (2016, p. 24) a convergent design is where “both the qualitative and quantitative data are collected more or less simultaneously; both data sets are analyzed and the results are compared”. The quantitative part is presented by calculating percentages based on the number of comments within certain groups that will become clear in the description of the methodology in the rest of the chapter. The percentages of each country are also compared with each other for a global overview.

The qualitative part is presented by an analysis of the comments of the participants. Sense making of the data involves consolidating, reducing and interpreting comments to constitute the findings of the study (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016, p. 202). Creswell (2013, p. 101) explains it as “understanding the complexity” of the data. It was decided to do a comparative analysis of the data as described by Strauss and Corbin (1995, p. 273). This type of analysis is characterised through “continuous interplay between analysis and data collection” and it allows for “ingenuity and [is] an aid to creativity”. A deductive form of reasoning was used. It involves “moving from a general principle to understanding a specific case” (DePoy & Gitlin, 2016, p. 4). In other words, the researcher begins with a certain framework and then applies this to explain a specific case or set of data.

In this study the analysis is based on a framework provided by Rusman, Tan and Firssova’s (2018) in their article “Dreams, realism and critics of stakeholders on implementing and adopting mobile Seamless Learning Scenario’s in Dutch Secondary education”. Data was collected by researchers, each one in their own country, by hosting workshops and applying Disney’s Creative Strategy method to gather data from various prospectives. The methodology is described in more detail in the following sections.

Disney’s Creative Strategy method (Disney method)

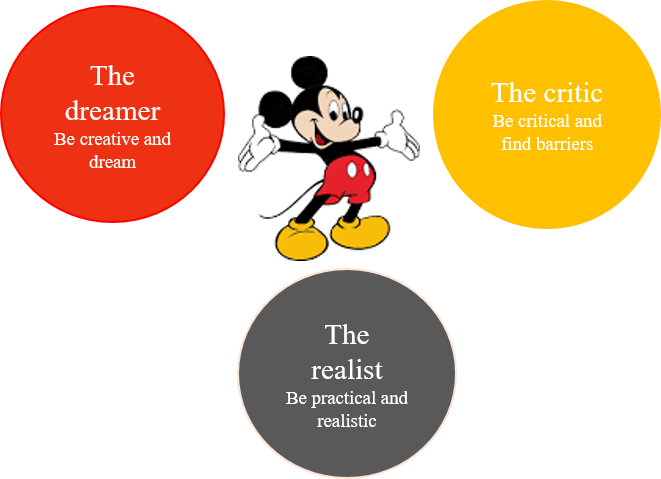

Walt Disney was described by one of his associates as having three characteristics “the dreamer, the realist, and the spoiler. You never knew which one was coming to the meeting” (Elmansy, 2015). In 1994 NLP specialist Robert Dilts cloned Disney’s method where people use a specific way of thinking to generate, evaluate and critique ideas to solve problems. This creative way of thinking unlocks the mind’s potential to dream and form solutions for specific issues. Balancing out the idyllic way of looking at a problem are the opinions of the realist and critical thinker to arrive at a viable outcome. Disney’s method, therefore, can be described as creative brainstorming to help turn the unthinkable into applicable projects. In Dilts’ (1994) own words:

Creativity as a total process involves the coordination of these three sub-processes: dreamer, realist and critic. A dreamer without a realist cannot turn ideas into tangible expressions. A critic and a dreamer without a realist just become stuck in a perpetual conflict. The dreamer and a realist might create things, but they might not achieve a high degree of quality without a critic. The critic helps to evaluate and refine the products of creativity.

Initially the same people were assigned three different roles, namely the dreamer, the realist and the critic. After imagining being in a specific role, the person moves onto the next character. According to Elmansy (2015) and McGuinnes (2009), the different roles can be described as follows:

The Dreamer

This role allows the person to share opinions without restrictions or criticism, resulting in a pool of creative ideas full of passion and enthusiasm. According to Rusman (2018), the dreamer looks at a problem from a positive, enthusiastic perspective where no issues or risks stand in the way. Certain questions asked by the dreamer are (Elmansy 2015; McGuinness 2009):

- What is the solution?

- What excites and inspires you about it?

- How do we imagine the solution?

- What are the benefits of applying the solution?

The Realist

When stepping into the role of the realist, plans must be put in place to realize the dream. This suggests a more logical way of thinking and creating ways to turn the idea into a manageable strategy. The person must not think about shortcomings and risks, but rather about concrete possibilities (Rusman, 2018). Questions that come to mind are (Elmansy, 2015; McGuinness, 2009):

- How can we apply this idea in reality?

- What resources do you need to make this happen?

- What is the action plan to apply the idea?

- What is the timeline to apply this idea?

The Critic

The primary role of the critic is to skeptically think about any barriers that may hinder the dream or concept to become a reality. Constructive critique is given regarding any flaws, possible problems, risks, obstacles or weak spots in the plan. Questions may include (Elmansy 2015; McGuinness 2009; Rusman 2018):

- What could be wrong with the idea?

- What are the disadvantages?

- What is missing?

- What are the weaknesses in the plan?

In our methodology, we assigned participants specific roles and did not let all of them take on all three positions. This was to streamline the process and save time. Rusman (2018) added a fourth role, namely the Observer. The Observer in her words “…is someone who is neutral towards the different perspectives and who summarizes each feedback during the plenary/feedback session”. This role was not included in this study per se. The researchers were taking on this role as they organized and observed the workshop from an objective perspective.

Ethical Clearance

Each of the researchers had to obtain ethical clearance or IRB (International Review Board) approval from their institution. This was a lengthy process for the researchers, because each higher education institution in each country had distinctive requirements which had to be collectively met.

Data Collection

Participants

Purposive, as well as snowball sampling, was utilized to recruit participants for the respective projects. Lecturers, instructors, professors, managers and coordinators in the respective higher education institutions were invited to participate in the study. Teaching staff from different departments were contacted via email and some by personal invitation. There were no inclusion/exclusion criteria except for the fact that they must be teaching staff of the specific institution. At some institutions, the workshop was repeated to increase the number of participants.

Workshop

The project was conducted in a workshop format. The same workshop format was followed by all researchers. After inviting participants and setting suitable dates and times the workshops were held at designated venues. The rooms were prepared by organizing tables and chairs in groups, seating between four and six participants per group. Every table presented one of the Disney roles and a specific color of post-it notes was placed on the table respectively. The realist for example were handed green post-it notes, the dreamer yellow and the critic pink notes. The three different colored post-it notes were to be used for writing down thoughts during the workshop by members of each group. Each participant received the program for the workshop, a short description of the seamless learning concept, an overview of the Disney method, a consent form for the ethical clearance and a short biographical questionnaire.

The original program of the workshop entailed the following sections:

- Welcome and introduction: The first twenty minutes of the workshop included a word of welcome, an introduction on the topic of seamless learning and a clarification of the method. A PowerPoint presentation compiled by Rusman (2018) was used for the presentations in all countries.

- Completion of consent form and biographical questionnaire. About ten minutes were assigned for the voluntary completion of the consent form and biographic questionnaire.

- Brainstorming sessions. The third part of the workshop entailed a twenty-minute brainstorming session within the respective roles assigned to each group. The mentioned, overarching statement/proposition postulated to the participants was: Seamless’ (learning) experiences should become a standard component within the curriculum of our institution. Each idea and thought were written on a separate post-it note.

- Feedback session. The post-it notes were attached to the notice board, and a group feedback-session, steered by one person followed for thirty minutes. During the feedback session the groups shared their thoughts with one another.

- Summary. At the end of the workshop the observer/researcher summed up the most relevant thoughts. He/she thanked the participants and explained what the next steps of the data collection would be. These steps are explained in the data analysis section below.

Data Analysis and Findings

Each of the researchers followed the same procedure for the data analysis by capturing the comments from the post-it notes on a spreadsheet in the three mentioned categories. Most of the researchers used the selected post-it notes colors from the workshop to distinguish the respective categories from each other. This procedure was followed to identify the statements again after categorizing them according to the coding scheme and framework of (Rusman, Tan & Firssova, 2018).

According to Onwuegbuzie, Leech, and Collins (2012) as well as Azungah (2018) a deductive analysis approach is one way to analyze data. This approach is used when you have a predetermined framework to analyze the data (Burnard et al., 2008, p. 429). Since this research project is based on a pre-existing study (Rusman, Tan & Firssova, 2018), as mentioned before, the themes and sub-themes that were used to do the deductive analysis are the following. The three main themes encompassed, 1.) the decision process, 2.) the change process and 3.) the design and implementation process. It must be clearly stated that what follows, are the statement of the components of the framework that were used to analyze the data. A complete description of the findings and analytical discussion of each set of data for each country will be presented in each chapter. This will be followed by the last chapter where all the strings will be pulled together.

The sub-themes for the decision process included 1.) costs, efforts, investment, dangers;

2.) benefits, surplus, value, results; 3.) technology; teachers’ competencies, attitudes; 4.) target group, suitability, competencies, attitudes; 5.) social expectancies, role requirements and national education curriculum.

The change process theme consists of the sub-themes: 1.) teacher professionalism; 2.) organizational management; 3.) evaluation and quality control; 4.) changing roles and responsibilities; 5.) change of daily school organization as well as a change of models, methods and approaches.

The themes 1.) technology; 2.) guidance, support, degree of autonomy of learners; 3.) social learning participation and involvement of the network, various social practices; 4.) learning objectives and learning results; 5.) assessment formative and summative, evaluation and testing; 6.) process-oriented design of interdisciplinary/ transboundary activities; 7.) experiential design of activities within school; 8.) safety-measures and insurance form the sub-themes of the third main theme, namely design and implementation process.

After conducting a deductive analysis process, the different data sets from the researchers were analyzed by means of a comparative content analysis. Through this type of analysis, a combination of factors is identified across multiple sets of data to produce a specific outcome (Cress & Snow, 2000, p. 1067). Reports on the different sets of data with unique remarks and observations are included in the various chapters to follow.

Limitations of the Study

The researchers’ interpretation of the data in each country cannot be without bias since variables such as their background, gender, culture, history, socioeconomic background, experience and attitude is not the same and cannot but have an influence on the interpretation of the data (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). Therefore the categorization and interpretations of the statements need to be considered from this stance. These differences are even more pertinent if more than one researcher is working on the data analysis. For this reason, only two researchers worked on the data of the final chapter.

Conclusion

To conduct the same research project in five different countries, on five different continents in different time zones, is a challenge in itself. However, to keep the data collection and data analysis aligned was another challenge and needed detailed guidelines and timelines. Besides that each country has its own rules, regulations and policies in terms of technology integration in higher education, each institution follows a specific set of guidelines for obtaining ethical clearance. To compare data from such a variety of backgrounds may be challenging and questionable. These challenges were all part of the challenge the research team encountered. Before addressing the global challenges, the researchers decided to focus on their countries first.

Thus, each researcher compiled a chapter in the form of an independent research study on seamless learning, grounded in their national and institutional context. Therefore the following chapters shed light on the background and the perspective on seamless learning in higher education in the context of Malaysia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa and the USA, correspondingly.

Looking ahead, this research may be used as a foundation for future studies in the area of seamless learning for education. These could include an analysis of the education policies of more countries; compiling a draft “blueprint” for implementing seamless learning as part of policies and curriculum and designing a strategy as well as step by step guidelines for lecturers regarding practical advice on implementing seamless learning. With this study we are embarking on an exciting journey into relatively unexplored territory.

References

Amemic, J. H., & Craig, R.J. (2000). Accountability and rhetoric during a crisis: Walt Disney’s 1940 letter to stockholders. Accounting Historians Journal, 27(2), 49-86.

Azungah, T. (2018). Qualitative Research: deductive and inductive approaches to data analysis. Qualitative Research Journal. Emerald Publishing Company.

Burden, K., & Kearney, M. (2016). Future scenarios for mobile science learning. Research in Science Education, 46(2), 287-308. doi:10.1007/s11165-016-9514-1

Burnard, P., Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008). Analyzing and presenting qualitative data. British Dental Journal, 429-432. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

Chan, T. W., Roschelle, J., Hsi, S., et al. (2006). One-to-one technology-enhanced learning: An opportunity for global research collaboration. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 1(01), 3-29.

Cress, D. M., & Snow, D. A. (2000). The Outcomes of Homeless Mobilization: The Influence of Organization, Disruption, Political Mediation, and Framing. American Journal of Sociology, 105(4), 1063-1104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3003888

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. SAGE.

DePoy, E., & Gitlin, L. N. (2016). Introduction to research: Understanding and applying multiple strategies (5th ed.). Elsevier.

Dilts, R. B. (1994). Strategies of genius (1st ed.). Open access: Meta Publishing.

Durak, G., & Çankaya, S. (2018). Seamless Learning: A Scoping Systematic Review Study. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 5 (4), 225-234.

Elmansy, R. (2015, April 6). Disney’s Creative Strategy: The Dreamer, The Realist and The Critic. [Web blog post]. Designorate. https://www.designorate.com/disneys-creative-strategy/

Herodotou, C., Aristeidou, M., Sharples, M., & Scanlon, E. (2018). Designing citizen science tools for learning: Lessons learnt from the iterative development of nQuire. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 13(1), 1-23. doi:10.1186/s41039-018-0072-1

Hofstein, A., & Rosenfeld, S. (1996). Bridging the gap between formal and informal science learning. Studies in Science Education, 28, 87-112.

Kuh, G. D. (1996). Guiding principles for creating seamless learning environments for undergraduates. College Student Development, 37(2), 135-148.

Merriam, H. B., & Tissdell, H. M. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

McGuinness, M. (2009). Lateral Action: The secret of Walt Disney’s creativity. [Web blog pPost]. Lateral Action. https://lateralaction.com/articles/walt-disney/?cn-reloaded=1

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Leech, N. L., & Collins, K. M. (2012). Qualitative Analysis Techniques for the Review of the Literature. The Qualitative Report, 17, 1-28.

Rusman, E., Tan, E., & Firssova, O. (2018). Dreams, realism and critics of stakeholders on implementing and adopting mobile Seamless Learning Scenario’s in Dutch Secondary education. In D. Parsons, R. Power, A. Palalas, H. Hambrock, & K. MacCallum (Eds.), Proceedings of 17th World Conference on Mob (pp. 88-96). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/184927/

Sharples, M., McAndrew, P., Weller, M., Ferguson, R., FitzGerald, E., Hirst, T., Mor, Y., Gaved, M., & Whitelock, D. (2012). Innovating Pedagogy 2012: Open University Innovation Report. The Open University.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1995). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 273-285). SAGE.

Wong, L. H. (2012). A learner-centric view of mobile seamless learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(1), E19–E23. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01245.x

Wong, L. H. (2015). A Brief History of Mobile Seamless Learning. In Wong, L.-H., Milrad, M., & Specht, M. (Eds.), Seamless Learning in the Age of Mobile Connectivity (pp.3-40). Springer.

Wong, L. H., & Looi, C. K. (2011). What Seams Do We Remove in Mobile Assisted Seamless Learning? A Critical Review of the Literature. Computers & Education, 57, 2364–2381.

Wong, L. H., Chai, C. S., Aw, G. P., & King, R. B. (2015). Enculturating seamless language learning through artifact creation and social interaction process. Interactive Learning Environments, 23(2), 130–157. https://doi-org.ezproxy.elib10.ub.unimaas.nl/10.1080/10494820.2015.1016534