Helga Hambrock and Frelét de Villiers

Introduction

The final chapter of this book includes a synthesis of the background, policies, technology, challenges and opportunities relevant for a seamless learning approach, as found in the Netherlands, Malaysia, the USA, South Africa and New Zealand. It further includes a summary of the perspectives of higher education instructors on seamless learning as found in the respective countries. The perspectives of the instructors are based on the following statement: ‘Seamless’ (learning) experiences should become a standard component within the curriculum of your institution’.

The uniqueness of the study lies in the fact that the topic is approached by instructors from different countries and thus an array of perspectives can be expected. Each countries’ contribution is considered of equal value and is included as part of the overall findings.

As an introduction, the status of the countries is presented and contains a summary of the background in terms of ICT in Education in each country. The challenges, the existing policies and technology access as well as a summary of each country’s position in terms of seamless learning is presented.

Thereafter the research methodology and the findings are discussed. To conclude an overall comparison and recommendation of the implementation of seamless learning from an international perspective is presented.

Background: ICT in Education

This section of the chapter includes the background of all the countries in terms of Policies and Technology access and challenges. These topics are discussed per country respectively.

Policies

Malaysia

The Malaysian National Philosophy of Education (Hudawi, et al. 2014) fosters learning in the new millennium and regards students as holistic human beings. The Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (Kementerian Pelajaran Malaysia, 2015a; Kementerian Pelajaran Malaysia, 2015b; Kementerian Pelajaran Malaysia, 2015c; Selamat et al., 2017) firmly pursues the goal of incorporating technology into the education system. This includes a long-term plan to apply digital literacy skills. A substantial budget increase for technical and vocational education has been allocated in the Malaysia Eleventh Plan 2016-2020 (Unit, 2015) to increase the quality of higher education studies in Malaysia.

So far tertiary institutions of Malaysia have not sufficiently been provided with software programs and devices, Wi-Fi coverage and e-learning platforms. Since these services and technologies are necessary for seamless learning, the tertiary education environment still has quite a way to go.

Relevant policies concerning technology integration in Malaysia include the E-Learning Policy, the Malaysia Education Blueprint for Higher Education, and the Seventh Malaysia Plan for Education 2013-2025. Last-mentioned advocates for teachers to benefit from ICT which must be a comprehensive tool in facilitating learning. This is reflected in services like mobile recharge kiosks and power supplies on campus. However, these policies focus on the availability of technology and not preparing instructors in terms of professionalization of teachers’ digital literacy

The Netherlands

The digital infra-structure to support digitized learning is in place in the Netherlands, as tertiary institutions are provided with fast broadband and Wi-Fi connections. The majority of students have more than sufficient access to (mobile and online) technology (Surf Net; 2016).

Trends on ICT, technology-enhanced learning and higher education in the Netherlands are found in the report of Surf Net (2016). Technologies offer the opportunity for students to have more control of their studies if they study full time or study while they work. They envision technology enhanced learning, including virtual reality, the internet of things, virtual classrooms as well as serious gaming and gamification. All of these factors are directly dependent on strong and steady technology access, for which the ICT infrastructure as well as ‘bring your own device’ coverage among students in the Netherlands is in place. Another report by Kennisnet, Schouwenburg and Kappert (2019), points out trends for learning which include support for authentic and flexible learning, provision of insight in own learning processes and further development of skills to prepare for future living, learning and working.

Ambitions set out by the Dutch Ministry of Education Kennisnet, Schouwenburg and Kappert (2019), can be realised by digitalisation. The last-mentioned include artificial intelligence, learning analytics, open badges, micro-credentials, serious games, as well as virtual and augmented realities. Currently, not many tertiary institutions in the Netherlands have implemented seamless learning in their curricula. There are only a few small-scale pilot implementations.

The term ‘seamless learning’ does not appear in government documents and policies per se’, but the paradigm aligns well with the envisioned objectives of the Dutch Ministry of Education. They set out guidelines in 2019 for the next four years. Two of the four goals are aligning with the seamless learning approach. These include 1. ) More flexible and tailored higher education and 2.) Close alignment of higher education with the labour market and society. In this context seamless learning can be regarded as the bridge between available technologies, current and pursued learning approaches and future visions.

USA

The digital infra-structure to support digitized learning is not a huge challenge in the USA as most tertiary institutions have been provided with fast broadband and Wi-Fi connections. The majority of students have more than sufficient access to technology and this was already found to be the case in 2016. In the National ECAR survey conducted in 2016 (Brooks & Pomerantz, 2017), it was established that more than 96% of the students have access to wireless services via their mobile devices. For students who cannot afford the devices a study by Graafland (2018) pointed out that one on one device provision increased from 55% in 2016 to 88% in 2018. It was also established that students use different devices, either separately, sequentially, or simultaneously.

The majority of the instructors are however, reluctant to use mobile technology as part of their classes. The reason is not that they are not trained; on the contrary, instructors are trained and can use technology in their classes but do not allow the students to use mobile devices. They said that it is distracting to themselves, as well as for others. They do however realise the benefits of including technology in their classrooms.

As early as 1998 a policy document, called the National Educational Technology Standards (NETS), was released in the USA by International Standards of Technology in Education (ISTE). The ISTE document sets out suggestions and requirements for using technology in the teaching and learning environment. Aspects like critical thinking, problem-solving and decision-making are emphasised in relation to creative innovation, communication skills, and collaborative work projects. The policy contains detailed suggestions for using technology to enhance learning from K-1 to Tertiary education levels. Seamless learning is not mentioned directly in the ISTE standards but accommodates its implementation within the policy (International Society for Technology in Education, 2007).

South Africa

The term ‘seamless learning’ does not appear in studies conducted in South Africa per se’. The terms that are found are blended, mobile or distance learning. Examples of such studies in the South African context include studies on blended learning experiences, transnationalism and blended learning. It is established in these publications that blended learning is an effective way to enhance the learning process. The term ‘resource-challenged communities’ is associated with South Africa, where access to mobile devices, internet services and even daily utilities like access to electricity is challenging and sometimes non-existing (Meintjies, 2018).

Three policies for higher education were published in 2014 (CHE, 2014; DHE, 2014) regarding distance (online) learning. The first one, “Policy for the provision of distance education in South African Universities in the context of an integrated post-school system”, was created by The Department of Higher Education and Training. The other two “Distance Higher Education Programmes in a digital era: Programme accreditation”, as well as “Distance higher education programmes in a digital era: Good practice guide” were published by the Council on Higher Education. However, seamless learning is not mentioned as a specific approach in one of these policies yet.

New Zealand

A digital strategy to improve country-wide digitalization was implemented since 2005. This focused mostly on improving the economy of the country. In 2011 the Network for Learning (N4L) initiative was launched to provide schools and tertiary institutions with uncapped ultra-fast broadband (MoE, 2019). Nation-wide connectivity was provided to businesses, public organisations and to tertiary institutes. The need to improve digital literacy was not only identified for students but also for teachers and instructors over the past years. Therefore the Ministry of Education launched a revised digital curriculum in 2020.

Technology Access and Challenges

Malaysia

The improvement of the technological infrastructure in the tertiary education environment is a priority for the government in Malaysia. The technical and vocational education budget was increased from 500 million Ringgit in the previous Malaysia Tenth Plan to 1 billion Ringgit Malaysia in the Malaysia Eleventh Plan 2016-2020. The change included a parallel education system in the form of a virtual platform known as Frog’s virtual learning environment (VLE). It is cloud-based and aims to provide a flexible and mobile virtual learning environment (Hamzah & Yeop, 2016). However, recently, the Frog VLE is no longer being used in schools and has been replaced with the Google Classroom (Rajaendram, 2019).

Support services, such as mobile recharge kiosks, charging booths as well as power supplies in numerous places, are currently provided and will change students’ lifestyles to become more versatile in the smart university environment (Nenonen, Wezel, & Niemi, 2019).

The following challenges regarding technological, economic, and social aspects were mentioned by the participants in the workshops. A lack of policies in terms of management and coordination of technology implementation was identified. Also a need for training of instructors and students on managing a seamless learning environment was mentioned. Another important point was highlighted by the participants, namely that educators do not all have the skill set to use mobile devices. Some feared that the devices would distract the students and that the smaller screen size can be obstacles.

Another challenge is that not enough support staff to manage ICT resources are available, and the cost of maintenance is high. The security of the devices is another challenging issue because of a high theft risk.

The infrastructure including WI-FI and internet access and maintenance in especially rural areas is another challenge. Cost of laptops and mobile devices creates affordability challenges for instructors and students.

Netherlands

According to the (Surf Net; 2016) trend survey, 100% of students in higher vocational education and 99% of students in universities already owned a mobile phone, 93% and 83% respectively a smart phone and 90% of both groups a laptop. So, 90% of students in higher education (research and applied science universities) owned both a smartphone and laptop. One may expect even higher access to technology now, as the study was done already 7 years ago. This means that access to (mobile and online) technology is available to most students and instructors in the Netherlands.

The high technological access and coverage of higher educational students within the Netherlands is an indication that interest in technology and the value of technology is important. The question as addressed in this study is how the technology is integrated in education with specific reference to seamless learning.

Despite the technology availability and high accessibility, not many studies have been conducted in the field of seamless learning in the Netherlands. This may be due to the unknown use of the term and unfamiliarity with underlying concepts.

USA

An ECAR survey (Brooks & Pomerantz, 2017) conducted in 2016 found that 96% of students own smartphones, 93% laptops and 57% tablets. It is interesting to note that 52% of the students own all three devices and that the most common combination is a laptop and a smartphone. Only 1% of the students do not own any devices (Brooks & Pomerantz, 2017). Access to technology may have grown over the past years.

These high percentages of technology ownership are even higher now and indicate that technology is important, but without a well-designed implementation strategy technology may not be effectively implemented for learning as it could be. The seamless learning paradigm is not as known as one would have expected.

Despite the high availability of mobile devices, educators still have reservations to include mobile technology as part of the curriculum and class. The need of pedagogical implementation strategies, including seamless learning have been identified (Siemens, Gašević & Dawson, 2015). Challenges for instructors include training and adopting a seamless learning strategy. ISTE technology standards are well-known throughout the USA, but the term seamless learning needs more specific attention (International Society for Technology in Education, 2007).

South Africa

Information on the digital landscape in South Africa is scarce, but a survey was done at the University of the Free State in 2017 that is a good indication of general trends. The survey was completed by two thousand two hundred thirty-six (2236) students and one hundred and fifty staff (150) members completed the survey. Aspects like technology ownership, use patterns, and perceptions of technology were covered. The most important (and relevant) findings are that 82% of students had access to smartphones and 18% access to tablets. Only 45% of the students had access to reliable internet when off-campus and 72% of staff members had access to the internet with their data, and 26% could access the internet in areas with open access to Wi-Fi. Challenges regarding the use of mobile devices were the cost of data (70%) and inadequate battery life (38%).

The biggest perceived challenge in South Africa are computer skills of students and lecturers, access to devices, resources, technologies, and support services. From the educators’ viewpoint, the initial time investment, lack of time to prepare, lack of innovative teaching strategies, course design and implementation, as well as assessment strategies, are hurdles to overcome. Inadequate computer skills, restricted access to technological resources, and a lack of data or Wi-Fi coverage when the students go back to their remote communities are challenges that students face.

New Zealand

The attention on a digital strategy can be traced back to 2005 when engagement with the digital economy was prioritized. Skill and confidence development, as well as infrastructure upgrades, were seen key for New Zealanders to improve engagement with technology. Involved and rounded educational experiences are the focus points of the education system in New Zealand. The supporting role of digital technologies in this quest is clear. Furthermore, the focus is on students as the creators of digital experiences and not merely consumers of technology.

A revised digital curriculum was launched in 2020 by the Ministry of education. It focuses on computational thinking for digital technologies and designing and developing digital outcomes to strengthen and embed digital skills at all levels. It offers opportunities for seamless learning.

Research Methodology

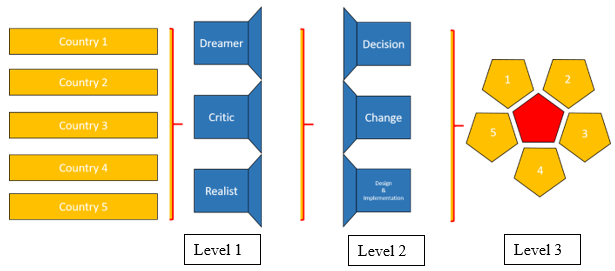

For this global research study where the researchers came from five different backgrounds, it was important to follow one research methodology. The research methodology included three levels. The first level included a brainstorming workshop session and collection of statements of instructors at five purposively selected higher education environments. The opinions of the participants were collected during workshop sessions. The roles of the participants included a dreamer, a critic and a realist perspective.

For the second level of this study, the researchers respectively categorized the collected statements by following a mixed method approach, where a qualitative inductive approach was firstly used to sort the statements from the first level into themes and categories based on the framework by Rusman et al. (2018). These categories included a decision process, a change and a design and implementation process. Then a deductive quantitative approach was followed by counting the statements in every category and calculating an overall percentage of the total statements. The aim was to find the mostly mentioned statements as matters of urgency and concern amongst teachers in their respective countries (chapter 2 – 6).

For the third level of the study a data analysis was conducted and the data retrieved from each country were accumulated and analysed comparatively. The statements were organised to establish the overall most relevant challenges.

Findings

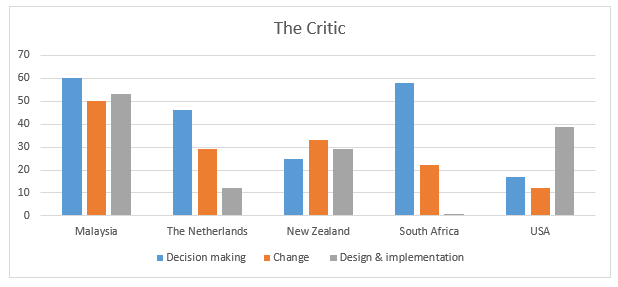

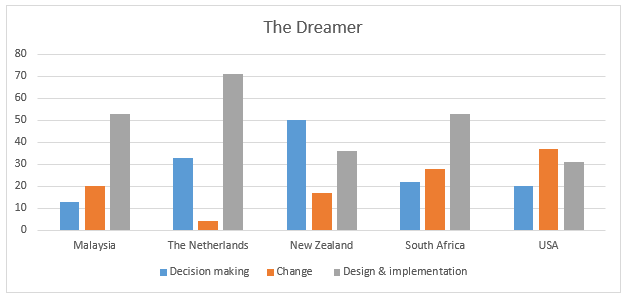

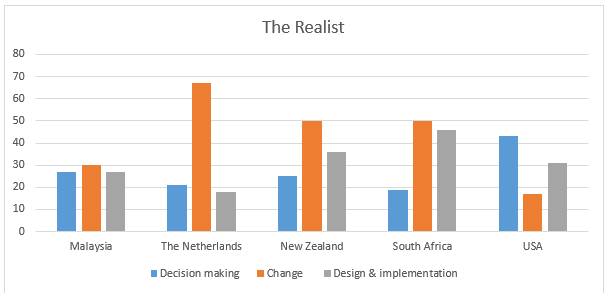

The findings from the Level 1 analysis focused on the analysis of the Critic-Dreamer-Realist perspectives. The findings are discussed in this order.

The most daunting matter for most countries from the critics’ perspective is the decision making process. From the dreamers’ perspective, the design and implementation process needed the most attention and from the realists perspective the change process was found to need the highest level of attention (Figures 7.2 to 7.4).

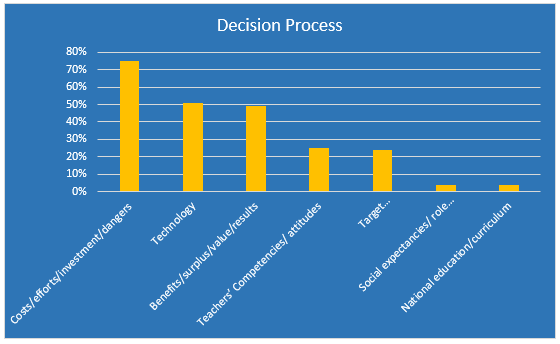

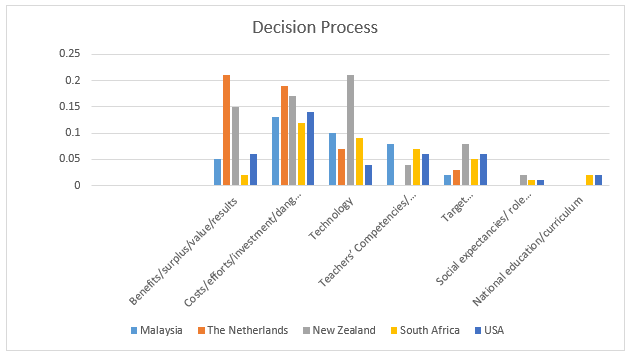

The figures following are representing factors retrieved out of all statements, independent of role.

The factors for the decision process are listed from highest to the lowest (most to least mentioned) from the combined data:

- Costs, efforts, investments and dangers. The concerns about the high cost, the amount of effort to implement a seamless learning approach for instructors and possible dangers for students were indicated as the overall highest concern.

- Technology affordability and accessibility was ranked as the next highest concern.

- Benefit, surplus, value and results with regard to learning

- Teachers’ Competencies/ attitudes

- Target group/suitability/competencies/ attitudes

- Social expectancies/ role requirements

- National education/curriculum integration

Most participants pointed to the cost to provide access of instructors and students to technology, whilst competencies and attitudes of teachers were also considered as influencing the decision. According to these findings these aspects were crucial before expectations and role requirements and seamless learning can even be considered to be integrated in the curriculum.

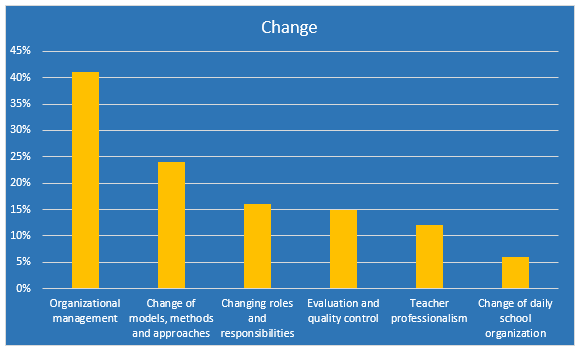

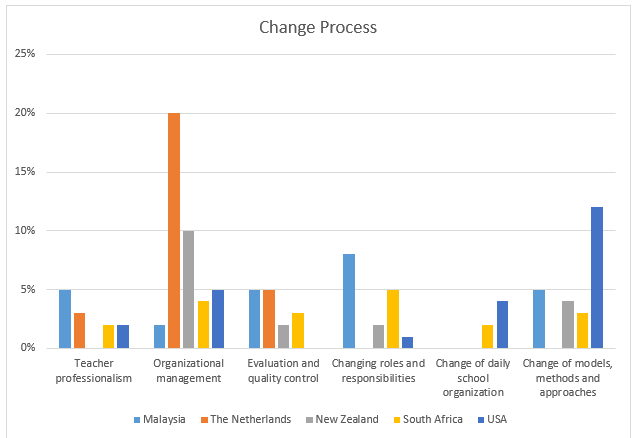

Figure 7.3 depicts the statements that needed attention or had to be implemented before changing to a seamless learning approach.

The factors within the change process as prioritized from highest to lowest are included:

- Organizational management

- Change of models, methods and approaches

- Changing roles and responsibilities

- Evaluation and quality control

- Teacher professionalism

- Change of daily school organization

Guidelines need to be in place for all role players beginning with management to instructors based on clear models, methods and approaches before change can transpire. Only then the daily school organization can be adjusted and implementation can be considered. More factors to be addressed before effective design and implementation can occur are presented in Figure 7.4.

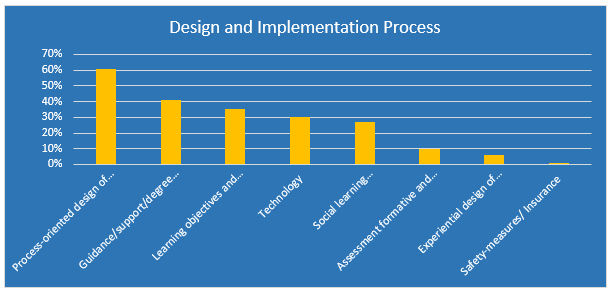

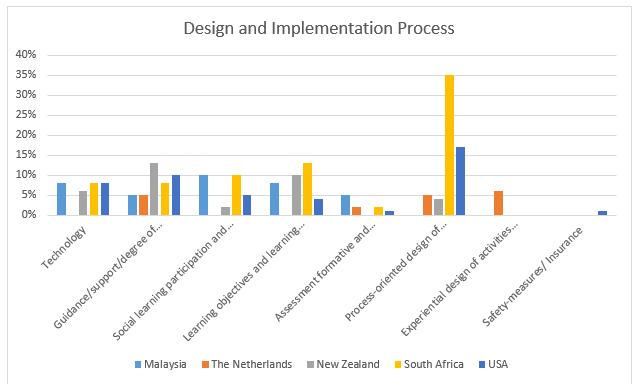

For the decision and implementation process the following factors are to be considered from highest to lowest priority:

- Process-oriented design of interdisciplinary / transboundary activities

- Guidance/support/degree of autonomy of learners

- Learning objectives and learning results

- Technology

- Social learning participation and involvement of network / various social practices

- Assessment formative and summative, evaluation and testing

- Experiential design of activities within school and in out-of-school environments/ settings

- Safety-measures/ Insurance.

To ensure that design and implementation for a seamless learning approach is effective, more detailed suggestions are made. The design should be process-orientated including an interdisciplinary/transboundary approach. Important is support for learners when needed with clear learning objectives. Technology availability for specific tasks, collaborative learning needs be added, evaluation and assessment needs to include formative and summative evaluation, in and out of school learning experiences are essential and safety measures including insurance need to be in place.

Discussion and Conclusion

The first part of the final discussion and conclusion consists of a summary of each countries’ readiness for seamless learning based on the existing literature. The second part is based on the findings of this study.

Malaysia

It is evident that good management and clear policies, as well as digital literacy skills, are important and still need to be implemented in Malaysia. Emphasis was placed on the 21st-century classroom preparation which would offer a seamless learning environment free of bureaucracy. Details like subsidised data, content accessibility, trained workforce and availability of devices for teaching and learning are regarded as important for successful implementation of seamless learning.

Although the Malaysian government is striving to implement high level technology for education they are not yet prepared for the implementation of seamless learning. Policies need to be adjusted and the decisions, changes and design of the process need to be based on addressing the above mentioned challenges for successful implementation.

Netherlands

Benefits of adopting seamless learning in the higher education environment include applying knowledge, connecting with professional environments, increasing flexibility and efficiency of learning through technology. Educators are however, sceptical about these benefits, since there is no evidence yet that costs involved in re-designing the modules will lead to success. Seamless learning is also not a viable option for all courses because of their content. Not all educators will be able to convert the content into seamless learning activities. A rather cautious approach by instructors towards implementation of the seamless learning concept, was noted by the researchers.

South Africa

The educators of this study are eager and enthusiastic to implement seamless learning. The unique challenges that South Africa as a developing country faces may slow down the process of implementation. A few examples are the high crime rate, poverty, accessibility to physical resources, limited access to Wi-Fi, high cost of data and transport problems. On university level the big classes, lack of computer literacy skills, negative attitudes of lecturers and students as well as the additional workload, re-curriculation of modules and existing assessment strategies are hindrances.

The most important aspects that were identified during the workshop that can help with the successful implementation of seamless learning include: the importance of positive attitudes; contact with experts; sufficient training; accessible, stable, free Wi-Fi; availability of handheld devices. Effective assessment strategies; comprehensive policies; excellent communication between all the relevant parties and lastly sufficient support staff and structure were also mentioned.

The USA

The most important issues that were evident from the study in the USA included that policies for implementing seamless learning need to be refined. Even though students in higher education institutions have up to 96% (Brooks & Pomerantz; 2017) access to technology the instructors still need to be convinced that ICT in education needs to be integrated into their teaching method. According to the 2016 (2019) the numbers of instructors using technology in their classes are as high as 74%, but still need to improve.

It is apparent that educators participating in this study were not aware of the term seamless learning but were positive, yet cautious, to implement the approach.

New Zealand

In order for seamless learning to be implemented successfully, a change in educational culture is still necessary. The outcome is to support learners to embrace self-regulated learning across all locations, tasks, and devices. Educators are positive and enthusiastic and want to support integrated enhanced learning opportunities. Technical and philosophical issues, however, stand in the way of full deployment.

Overall result

After addressing the perspective of instructors on seamless learning on various levels some surprising results were found. Firstly, one needs to note that most participants had not encountered the term ‘seamless learning’ before and only had a better understanding of the concept after the introduction of the term during the workshop. This may be one of the main reasons why seamless learning has not been implemented in most countries.

Another finding, which is also supported by the adoption theory of Rogers (1995), is that most instructors prefer to continue with methods and approaches they have used over the years and are reluctant to introduce new approaches. This can be interpreted as an innate fear of unknown territory on the one end of the continuum and a certain amount of clinging to their comfort zone on the other end which could be due to feeling incompetent to do so yet. Thus resulting in a laggard approach towards change. Therefore, before the implementation of seamless learning can be suggested, it is of utmost importance to ensure that all instructors know what is meant by seamless learning. The high number of statements from each perspective referring to the need of training, is supporting this finding. Based on the findings the instructors agree that seamless learning should be included in the curriculum of their respective country.

Although each country has its own levels of priorities and not one is exactly the same as the other, an overall trend can be recognized. These factors that are found as a priorities under each process include: access to technology, the instructor’s competence, attitude and professionalism. These are important findings since the instructors refer to the importance of these aspects themselves.

Notwithstanding the fact that different countries deal with different challenges and may have different advantages and disadvantages in their own context, the instructors have one thing in common- they are all living in a time of change in which technology is evolving. This calls for a solution which can be applied by all.

Thus, the results as found by the researchers from all five countries, suggest that a seamless learning strategy can and should be implemented in the curriculum of higher education in each respective country. However, considering that these countries are in five different continents, their suggestions can also be considered as a global view. This study therefore suggests that an overarching global seamless learning strategy, which includes all recommendations, should be planned, designed and implemented.

This means that supporting policies need to be developed to implement seamless learning locally and globally. The next step as encouraged by this study should be to “stop speaking”, as suggested by Walt Disney (Newmark, 2007), and to design and implement a seamless learning strategy to the global tertiary education curriculum.

References

Brooks, D. C., & Pomerantz, J. (2017). ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology. Research Report, Louisville 4(3), 3.

Council for Higher Education (CHE). (2014). Distance Higher Education Programmes in a Digital Era: Good Practice Guide. CHE.

Council for Higher Education (CHE). (2014). Distance Higher Education Programmes in a Digital Age: Programme Accreditation Criteria. CHE.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. SAGE.

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2014). Policy for the Provision of Distance Education in South African Universities in the Context of an Integrated Post-school System. Government Gazette No 37811, 7 July 2014, No 535. DHE.

Graafland, J. H. (2018). New technologies and 21st century children: Recent trends and outcomes. OECD Education Working Papers, no. 179.

Hamzah, M., & Yeop, M. A. (2016). Frog VLE (Virtual Learning Environment) in teaching and learning: Acceptance and method of implementation. Journal of Research, Policy & Practice of Teachers & Teacher Education (JRPPTTE), 6(2), 67-68.

Hudawi, S. H., Musah, M. B., & Fong, R. L. (2014). Malaysian National Philosophy of Education Scale: PCA and CFA Approaches. Asian Social Science, 10(18), 164-164. doi:10.5539/ass.v10n18p163

International Society for Technology in Education. (2007). National educational technology standards for students. ISTE

Kementerian Pelajaran Malaysia (2015a). Malaysia E-Learning Policy 2.0. http://smart2.ums.edu.my/pluginfile.php/2/course/section/2/Depan-20_2.pdf

Kementerian Pelajaran Malaysia (2015b). Malaysia Plan -11th. https://www.pmo.gov.my/dokumenattached/speech/files/RMK11_Ucapan.pdf

Kementerian Pelajaran Malaysia (2015c). National Education Blueprint Higher Education (2015-2025). http://mohe.gov.my/muat-turun/awam/penerbitan/pppm-2015-2025-pt/5-malaysia-education-blueprint-2015-2025-higher-education

Meintjies A. (2018). Digital Identity of staff at the UFS: 2018. UFS Centre for teaching and learning

Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap (2019). Strategische agenda hoger onderwijs en onderzoek. Houdbaar voor de toekomst (Fit for the future). https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2019/12/02/bijlage-1-strategische-agenda

Ministry of Education (2017). Digital Technologies | Hangarau Matihiko. https://education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/consultations/DT-consultation/DTCP1701-Digital-Technologies-Hangarau-Matihiko-ENG.pdf

Newmark, J. (2007). From Talk to Action: What Performance Improvement is Really All About. Radiology management, 29(3), 18.

Rajaendram, R. (2019, June 29). Google Classroom Gets Nod. The Star. https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/06/29/google-classroom-gets-nod

Selamat, A., Alias, R. A., Hikmi, S. N., Puteh, M., & Tapsi, S. M. (2017). Higher education 4.0: Current status and readiness in meeting the fourth industrial revolution challenges. Redesigning Higher Education towards Industry, 4, 23-24.

Siemens, G., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2015). Preparing for the digital university: A review of the history and current state of distance, blended, and online learning. Athabasca University.

Surf Net (2016, November). Trend report 2016: How Technological Trends Enable. [PDF file]. https://www.surf.nl/files/2019-03/trend-report-2016.pdf

Sandelowski, M. (2001). Real qualitative researchers do not count: The use of numbers in qualitative research. Research in nursing & health, 24(3), 230-240.

Schouwenburg, F., & Kappert, J. (2019). Onderwijsvernieuwing met technologie. Een internationale blik. Zoetermeer: Kennisnet. https://www.kennisnet.nl/app/uploads/kennisnet/publicatie/Kennisnet-Onderwijs-vernieuwen-met-technologie-een-internationale-blik-publicatie.pdf

Unit, E. P. (2015). Eleventh Malaysia plan, 2016-2020: Anchoring growth on people. Prime Minister’s Department.

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations (4th ed.). The Free Press.

Addendum 7.1

Comparison

The Critic

Table 7.1: The Critic’s Perspective

| Malaysia | The Netherlands | New Zealand | South Africa | USA | |

| Decision making | 60% | 46% | 25% | 58% | 17% |

| Change | 50% | 29% | 33% | 22% | 12% |

| Design & implementation | 53% | 12% | 29% | 1% | 39% |

The Dreamer

Table 7.2: The Dreamers’ Perspective

| Malaysia | The Netherlands | New Zealand | South Africa | USA | |

| Decision making | 13% | 33% |

50% |

22% | 20% |

| Change | 20% | 4% | 17% | 28% | 37% |

| Design & implementation | 53% | 71% | 36% | 53% | 31% |

The Realist

Table 7.3: The Realists’ Perspective

| Malaysia | The Netherlands | New Zealand | South Africa | USA | |

| Decision making | 27% | 21% | 25% | 19% | 43% |

| Change | 30% | 67% | 50% | 50% | 17% |

| Design & implementation | 27% | 18% | 36% | 46% | 31% |

Decision Process

Table 7.4: The Decision Process

| Category/factor | Malaysia | The Netherlands | New Zealand | South Africa | USA |

| Benefits/surplus/value/results | 5% | 21% | 15% | 2% | 6% |

| Costs/efforts/investment/dangers | 13% | 19% | 17% | 12% | 14% |

| Technology | 10% | 7% | 21% | 9% | 4% |

| Teachers’ Competencies/ attitudes | 8% | 0% | 4% | 7% | 6% |

| Target group/suitability/competencies/ attitudes | 2% | 3% | 8% | 5% | 6% |

| Social expectancies/ role requirements | 0% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 1% |

| National education/curriculum | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 2% |

| Subtotal | 38% | 47% | 67% | 38% | 37% |

Change Process

Table 7.5: The Change Process

| Malaysia | The Netherlands | New Zealand | South Africa | USA | |

| Teacher professionalism | 5% | 3% | 0 | 2% | 2% |

| Organizational management | 2% | 20% | 10% | 4% | 5% |

| Evaluation and quality control | 5% | 5% | 2% | 3% | 0% |

| Changing roles and responsibilities | 8% | 0% | 2% | 5% | 1% |

| Change of daily school organization | 0% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 4% |

| Change of models, methods and approaches | 5% | 0% | 4% | 3% | 12% |

| Subtotal | 25% | 28% | 18% | 19% | 24% |

Design and Implementation Process

Table 7.6: The Design and Implementation Process

| Malaysia | The Netherlands | New Zealand | South Africa | USA | |

| Technology | 8% | 0% | 6% | 8% | 8% |

| Guidance/support/degree of autonomy of learners | 5% | 5% | 13% | 8% | 10% |

| Social learning participation and involvement of network / various social practices | 10% | 0% | 2% | 10% | 5% |

| Learning objectives and learning results | 8% | 0% | 10% | 13% | 4% |

| Assessment formative and summative, evaluation and testing | 5% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 1% |

| Process-oriented design of interdisciplinary / transboundary activities | 0% | 5% | 4% | 35% | 17% |

| Experiential design of activities within school and in out-of-school environments/ settings | 0% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Safety-measures/ Insurance | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

| Subtotal | 36% | 18% | 38% | 76% | 39% |