Frelét de Villiers

Introduction

This chapter is the culmination of research done at the University of the Free State as part of the collaborative global research project, initiated at the MLearn conference in Chicago, Illinois, in 2018. The study aims to gain insight into lecturers’ perspectives at tertiary institutions that influence acceptance and adoption processes of mobile seamless learning scenario. Their perception of benefits as well as barriers towards adopting seamless learning scenarios in the tertiary education curriculum is explored.

The concept ‘seamless learning’ originated in the educational environment, where it was used to describe the students’ experiences during technology integration, both inside and outside the classroom (Wong, 2015). Seamless learning was revived with the publication of Chan, Roschelle, Hsi et al.’s (2006) seminal publication, One-to-one technology-enhanced learning: An opportunity for global research collaboration. They postulated that a seamless learning space consists of “scenarios in which learners are active, productive, creative and collaborative across different environments and settings” (Chan et al., 2006, p. 10). This is an opinion shared by Sharples et al. (2012, p. 24), who also states that learners experience continuity of learning across environments and settings at different times.

According to Wong and Looi (2011), seamless learning is conceptualized as connecting learning experiences and learning activities through technology-supported learning scenarios by using handheld devices. The learning process is supported, improved, and enhanced by this technology in both formal and non-formal contexts. Context plays an important role because it links concepts with the real world (Westera 2011, p. 201); it allows students to apply knowledge and put it into action (Lave & Wenger, 1991); thereby acknowledging learning as a social, co-construction process where knowledge is contextualized (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 1999; 2006). Seamless learning in these different contexts has the advantage of retention and transfer of learning to other situations, the involvement of third parties, as well as supporting behavioral changes of individuals through awareness and reflection (Rusman, Tan & Firssova, 2018). In order for this to be successful, the stakeholders must be supportive, involved, and cognizant of the fact that seamless learning is not merely the adding of digital technologies to an existing module, but that it must be aligned with the mission and vision of the institution (Vaughan et al., 2017, p. 103).

Background of Seamless Learning in South Africa

South Africa has a population of 59, 6 million people, of which 30, 5 million is female and 5, 3 million 60 years and older (Stats SA, 2020). The approximately 1, 2 million square kilometers (472 000 square miles), of South Africa, comprising of a geographically varied landscape. It includes wide-open savannahs, fertile plains, and the most beautiful, majestic mountains (Siyabona Africa, 2020). The Atlantic Ocean on the west side and the Indian Ocean on the east side border the coastal lines of the country. The country is divided into nine provinces, and there are eleven official languages.

A Living Conditions Survey conducted in 2015 found that 49, 2% of adults 18 years and older lived below the upper-bound poverty line. The unemployment rate in 2019 was 28, 1% (Stats SA, 2020). 94% of internet users up to 64 own a smartphone (Kemp, 2020). Although there are seven leading companies providing internet service in South Africa, the majority of students do not have access to the internet (see the section Technology access below). One of the reasons is that there is not necessarily coverage in the areas where the students reside. Secondly, the data rates are costly if you cannot afford to buy in bulk, but in megabytes. As stated by Bottomley (2020, p. 1): “if you can’t afford to buy in bulk, then the cost per megabyte becomes absurdly expensive”.

When moving on to research regarding seamless learning in the South African context, a vast and interesting array of research has been done in the field of technology-integrated teaching and learning. Aspects such as learner engagement, learning management versus classroom management, and the accommodation of multilingualism are being researched. However, the focus of this study is refined to studies in the field of seamless learning.

Available Studies

Upon conducting an EBSCO-host search and an elementary Google search on specific keywords in relation to South Africa (see Table 5.1), many results are presented. However, most of them have open and distance learning (Fressen, 2018) as the core concepts. Unfortunately, this is not the same as seamless learning. The terms hybrid or blended learning are more acceptable, and upon closer analysis, it is clear that these words are sometimes used interchangeably with seamless learning. The understanding of seamless learning from the researcher’s perspective is based on the approach of Wong et al. (2015) which includes ‘moving learning from in-class to out-of-class experiences’ by using various technologies. Blended learning also falls in this category and is thus considered as part of the seamless learning approach.

Table 5.1: Comparison of specific keywords in the South African context

| Keywords | Google search | EBSCO-Host search | |

| Hits | Relevant | ||

| Seamless learning | 12 100 000 | 88 | 21 |

| Contextualized learning | 614 000 | 141 | 5 |

| Good practice, seamless, contextualized | 1 730 000 | 153 | 34 |

| Trend reports of ministries of education | 59 600 000 | 52 | 2 |

| Use of ICT in education and seamless learning | 1 860 000 | 53 | 11 |

The other defining aspects of seamless learning, namely handheld devices and different contexts are also absent in the studies. E-learning is another buzz word. It usually means that content is available on Blackboard (Kleinveldt et al., 2016), an online learning and teaching application (Blackboard, 2018), or on computer programmes (Tshuma, 2012; Hiralaal, 2012). Other studies include an investigation of meaningful blended learning experiences (Nel, 2005); transnationalism and blended learning in the theatre classroom (Cloete et al., 2015) and blended learning for large classes (Bati et al., 2014).

Best Practices

From the literature review, it is clear that incorporating seamless learning can be positive in the sense that it can improve student access and success. According to Vaughan et al. (2017, p. 105), it can “extend access to new populations of students, alleviate the demand on physical infrastructure, and enhance the process of teaching and learning for the diverse body of students.” It is also stated that it can enhance the cognitive experiences of the students. The North-West University in Potchefstroom (South Africa) is a forerunner when it comes to the implementation of blended learning in South Africa. They have identified four benefits (Vaughan et al., 2017, p. 106):

- It provides flexible opportunities for learning.

- Students take responsibility for their learning by engaging in different individual and collaborative assessment and learning activities.

- The environment is conducive for students who thrive on active, responsive, and meaningful engagement.

- It can promote teaching and learning innovation and foster learning outside the formal lecture hall.

Other positive aspects of blended (seamless) learning are elucidated by Pillay and Gerrard (2011), who conducted a qualitative study with first-year Social Work students. The majority of the students reported that blended learning is an effective way to enhance the learning process. From the lecturers’ side, it seems that course design and implementation are problems. Vaughan et al. (2017, p. 103) identify a lack of time, resources, understanding and definition of the concept as challenging, but also reflect on the positive side, i.e. that lecturers become more reflective of their practice and adjust their roles accordingly. The lack of implementation or adoption of seamless learning can be attributed to “inadequate computer skills, lack of time to prepare new and appropriate teaching and learning materials, students’ restricted access to technological resources, and a lack of innovative teaching strategies…” (Vaughan et al., 2017, p. 108)

Although South Africa has “widespread access to technology” (Laaser, 2006), we have many remote communities without data or Wi-Fi coverage (Gillwald et al., 2012). Tshabalala et al. (2014, p. 101) mention “policy, faculty support by management, computer skills of students and lecturers, as well as inadequate access for students to computers…” as obstacles. Access to resources, technologies and support services such as computers, online environments, video conferencing and tutorial support can also hinder the implementation of blended learning (Basitere & Ivala, 2017; Prinsloo & Van Rooyen, 2007, p. 63). Basitere and Eunice (2017) call it “inherent[ly] resource intense” which can pose challenges to those who do not have access to all the resources. This is called resource-challenged communities – a term coined by Lazem (2019). They (Basitere & Eunice, 2017) even suggest that it can “further accentuate digital divide, marginalizing poorly resourced communities.” Above and beyond these challenges, it is essential to integrate technologies in order to create “sensorily (sic) and conceptually rich environments.” (Prinsloo & Van Rooyen, 2017, p. 52)

Policies

The Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) compiled a policy that was published in 2014, entitled Policy for the provision of distance education in South African Universities in the context of an integrated postschool system. In this document, ground rules are established regarding the contribution and purpose of distance university education, steering mechanisms, as well as enabling environments for expanded and cross-border distance education. The Council on Higher Education (CHE) also published two documents in the same year (2014), entitled Distance Higher Education Programmes in a digital era: Programme accreditation, as well as the guide that accompanies it, Distance higher education programmes in a digital era: Good practice guide. The last mentioned was published to clarify the distinctions between contact and distance education, as well as to provide guidelines of accreditation requirements for distance learning, with its different variations. This includes the effective integrating and support of Information and Communication Technology services.

In light of the absence of existing policies regarding the use of mobile learning (Ruth, 2017: 38; Tamukong, 2007), the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) suggested guidelines for the adoption of mobile learning. These include, inter alia, creation of mobile learning policies, providing of support and training, optimising educational content, improving connectivity options, providing equal access, and promoting the responsible use of mobile technologies (UNESCO, 2011: 29).

Technology Access

Scholarly articles on access to technology in relation to seamless (blended) learning in South Africa is scarce. There have been a few studies on ICT and the school environment (Assan & Thomas, 2012; Jita, 2016; Ogbonnya, 2010) but not necessarily for the higher education sphere. Regarding the digital identity and access to the technology of students and lecturers at the University of the Free State, a digital survey was conducted in 2017 in order to develop a holistic overview. The survey explored technology ownership, use patterns, and perceptions of technology. The respondents included 2236 students and 157 staff members.

Some of the important findings from the student survey that have a bearing on seamless learning follow here. The majority of students (82%) had access to smartphones, and less than a fifth (18%) had access to tablets. They (69%) believed that smartphones were important in their learning, but they did not always have access to reliable internet off-campus (45%). When off-campus, 72% accessed the internet with their personal data, while 26% accessed it from areas with open access to Wi-Fi, such as restaurants and coffee shops. Students (54%) reported that they got more actively involved in modules that used technology. The most popular social media platforms were WhatsApp, Facebook and YouTube. The majority of respondents thought that lecturers used technology to enhance the learning experience both inside and outside of the classroom. Respondents who made use of smartphones mostly used the devices to look up information (63%), photograph information (62%), and to record classes (41%). The challenges respondents most frequently experienced with smartphones as a teaching and learning tool, were the cost of data (70%), inadequate battery life (38%), and limited access to reliable internet (38%) (Meintjies, 2018 (a)).

Some of the most noteworthy findings arising from the survey of the lecturers follow here. The majority believed that laptops and smartphones were important in teaching and learning and that teaching with technology-enhanced their teaching experiences, as well as students’ learning experiences. Academic staff (29%) did not always have access to reliable internet off-campus. The biggest perceived benefits of online assessment were reduced marking time and rapid feedback to students, while the biggest perceived challenges of online assessment included a significant initial time investment and that it was challenging to prevent cheating. More than 60% of respondents indicated that teaching with technology helped their students learn more effectively, aligned with the pedagogy that they employed in their teaching, and would lead to innovative breakthroughs in teaching. Only about a fifth of respondents indicated using tablets or iPads as learning tools, and even fewer respondents used smartphones as a learning tool. The main reasons were the costs of the devices and data services. The majority of respondents indicated that they preferred a blended teaching environment (Meintjies, 2018 (b)).

Research Methodology

In this qualitative research study, purposive, as well as snowball sampling methods, were used to recruit the participants for the data collection. The latter consisted of feedback from a workshop and data retrieved from biographic questionnaires. The research methodology that was followed is explained in the first chapter of this book and aligns with the research practice of the other studies in this book. The data collection procedure, participant recruitment and profile, format are specific to this chapter and are discussed below.

Data Collections Procedure

Obtaining ethical clearance is an important aspect of any research (Thomas, 2017, p. 40), as it grants protection to participants and the researcher alike (Mertler, 2012, p. 103). Clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of the Humanities at the University of the Free State (number UFS-HSD2019/0410). Hereafter I sent out personalised invitation emails to 58 part-time and full-time academic staff from different departments. Participation information sheets, as well as consent forms, accompanied these emails.

Attendees

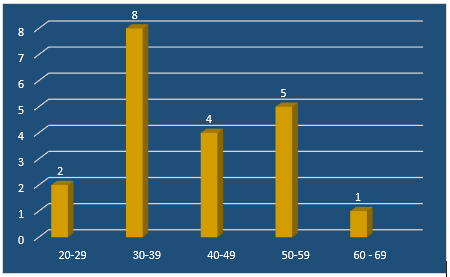

Twenty staff members replied positively and attended the workshop held at the Odeion School of Music on campus. The contingent consisted of five male and 15 female participants, ranging in age from 25 to 63 (see Figure 5.1), with one to 26 years of experience each.

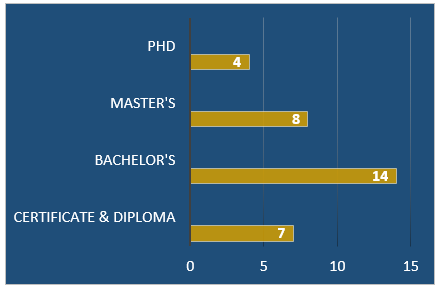

They represented a core group across the spectrum, namely policy makers, senior directors, heads of department, and lecturers. Departments that were represented included law, music, nursing, innovation, and history. Their descriptions of their expertise included concepts such as management, law, virtual teaching, music, marketing, branding, corporate experience, education, policy making, arts, instructional design, research, literacy skills, integrated learning, and applied linguistics. The participants’ primary involvement in the workplace is represented in the graph below (Figure 5.2).

Format

The venue for the workshop was prepared by arranging four different tables with five chairs each, as well as a notice board for the different groups. Documentation consisted of an information sheet explaining the concept of seamless learning, as well as the procedure of the workshop, letters of consent to sign (as this is important according to Lichtman (2013, p. 53), and Mertler (2012, p. 103), as well as a requirement of the ethics committee of the UFS), sticky notes and a little thank you gift for each participant.

The sixty-minute workshop unfolded in three different stages, i.e. a presentation, completion of forms, and the reflection and discussion. Aided by a PowerPoint presentation regarding the concept of seamless learning (as explained by Uosaki et al. (2013), and Wong & Looi (2011)), and an explanation of the Disney method of data collection (McGuinness, 2009; Elmansy, 2015) was explained. The participants were then requested to complete a voluntary biographical questionnaire, as well as the consent forms. Personal reflections, embedded in the role assigned to each participant, on the proposition “‘Seamless’ (learning) experiences should become a standard component within the curriculum of the University of the Free State”, were written on the sticky notes. There was an equal distribution of the three different roles assigned to the participants.

The respondents were given twenty minutes to complete the personal reflections, after which a collaborative, round table discussion, steered by the researcher, followed. Sticky notes were posted on the notice boards. The workshop concluded with feedback from each group and closed with general remarks.

Data Analysis

A deductive data analysis approach was followed for analyzing the raw data. According to Burnard et al. (2008, p. 429), the deductive approach involves using “a structure or predetermined framework to analyze data.” When researchers are already aware of possible responses, it makes sense to use this type of analysis. This was the case with the present study because the research was based on a previous study conducted by one of the researchers. The difference with the previous study was that the participants consisted of secondary school teachers. Unfortunately, according to Burnard et al. (2008, p. 430), this approach may be biased because “the coding framework has been decided in advance”.

Inductive Analysis

To counter this concern, the researcher conducted an inductive analysis as well. This type of approach is characterized by a reiterative process between the database and the themes until a comprehensive set of themes is established (Creswell, 2013, p. 45). Burnard et al. (200, p. 430) describe inductive analysis as “analyzing data with little or no predetermined theory, structure or framework and uses the actual data itself to derive the structure of analysis.”

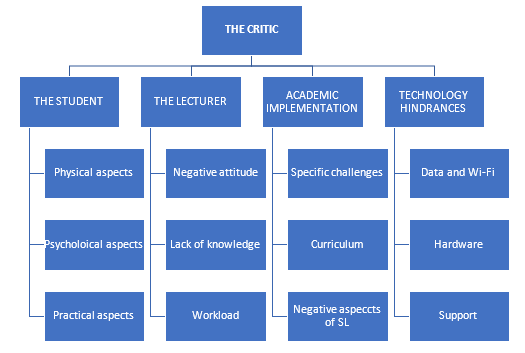

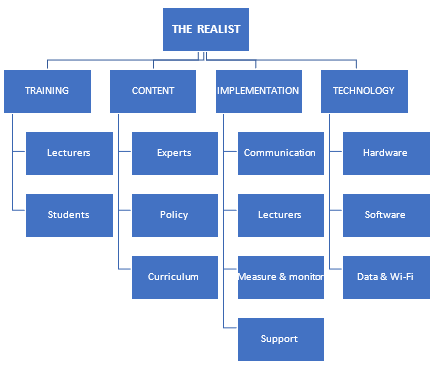

The twenty participants wrote down one hundred and eighty-four statements. Forty-eight came from the Critics’, seventy from the Dreamers’ and sixty-nine from the Realists’ perspectives. The following themes and sub-themes were identified for each role by following an inductive analysis of the data. In table 5.5, 5.6 and 5.7 (see Addendum 5.1), the themes and sub-themes are further illuminated by examples of comments made by the participants.

The Critic

The Realist

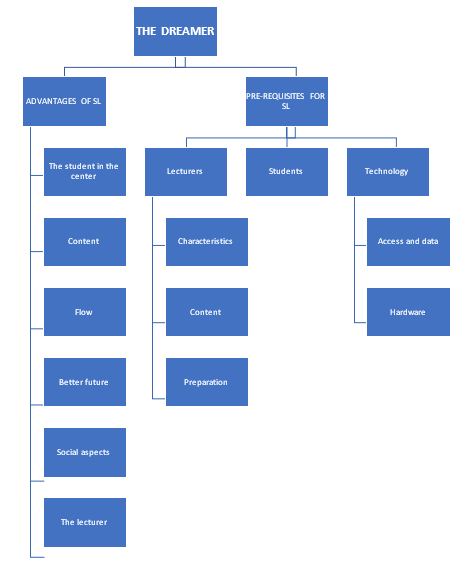

The Dreamer

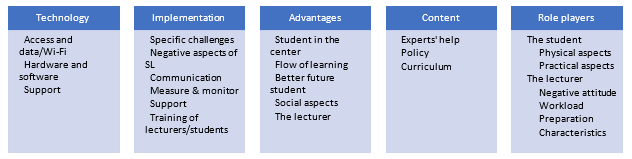

After further analysis of the data more detailed information is found. Five themes are identified namely technology, implementation, advantages, content, and role players (see Table 5.2). The sub-themes are added under the themes in Table 5.2.

Table 5.2: Themes from the inductive analysis of the data

Deductive Analysis

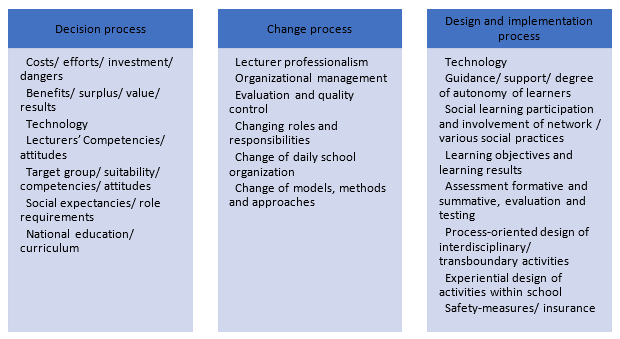

For the deductive analysis of the set of data the given framework was used (please see Chapter 1 for the detailed description of deductive analysis and the framework used for this research). The framework consisted of three main themes, i.e. the ‘Decision process’, the ‘Change process’, and the ‘Design and implementation’ process. Each comment was again carefully categorized by using these themes. See these themes and statements in Table 5.3.

Table 5.3: Themes from the deductive analysis of the data

More detailed information is available in Tables 5.8 – 5.10 (see Addendum 5.1). A summary of the number of statements and percentages of the total number of comments according to the perspectives as categorized per process, is presented in Table 5.4.

Table 5.4: Summary of perspectives and categories

| Decision making

process (67 comments in total) |

Change process

(36 comments in total) |

Design & implementation

process (81 comments in total)

|

|

| Critic

|

39 (58.2%) | 8 (22, 2%) | 1 (1, 2%) |

| Dreamer

|

15 (22, 4%) | 10 (27.8%) | 43 (53.1%) |

| Realist

|

13 (19.4%) | 18 (50%) | 37 (45.7%) |

Findings

In this section the statements are categorized and explained. The main themes as identified and the sub themes within each main theme is explained in more detail.

The Decision Processes

For the sub-theme ‘Costs/effects/investment/dangers’ an overwhelming array of comments was found, and these came from the perspective of the critics. The biggest concern was the accessibility to physical resources, including transport problems, health and safety risks on excursions, as well as equality of interactions. The latter is related to particular issues mentioned, i.e. limitations of funding to use the latest technology, as well as data costs and connectivity issues. Time management was also stated.

From the lecturer’s viewpoint the class sizes, faculty-specific needs, the differentiated base knowledge level of the students, and professional diversity within a speciality such as law, were seen as challenges that needed to be part of the decision-making process. Some participants felt so strongly about this that they were adamant that seamless learning might limit academic freedom and “It may hamper the culture of scholarliness.” The lecturers may have lacked computer literacy skills and may have been “unable/unqualified/uncomfortable” with having to incorporate seamless learning.

Moving on to the sub-theme ‘Benefits/surplus/value/results’, the researcher could only find a few comments, and, perhaps not so surprisingly, all were from the Dreamer’s perspective. It was postulated that students would be better employers because of the practical experience and that they would be “better equipped for life after graduation.” It was seen as a benefit that the students would be exposed to the “reality of [their] future work” and not only have textbook knowledge.

Aspects regarding ‘Technology’ were voiced in almost equal quantities by the Realist, Dreamer and Critic. A common concern that arose from all three roles was Wi-Fi accessibility. This encompassed ubiquitous Wi-Fi for staff and students (at least across campus), in the sense of hotspots and stable, high-speed Wi-Fi networks. The Critic was concerned about the university’s servers when embracing and implementing an online, blended approach, especially regarding whether they would be able to provide the prerequisite support and infrastructure. This amalgamated with statements that the technology was not ready yet, and that “data and technological challenges may demotivate learners and lecturers.” The possibility of devices being stolen was of great concern. It was also mentioned that data (and even the technology) should be free, and “every student must be given access to online learning.”

When we look at the sub-theme ‘Lecturers’ competencies/attitudes’, only the Realist and Dreamer made comments in this regard. The Realists spoke from one mouth when commenting on the provision of efficient training for the staff. They stated that this should take the form of workshops, and training by “experts in both teaching and learning”, as well as in the “effective use of the apps/technology required.” Lecturers need to understand what good practice entails and “a document and resources must be made available.” Through this, the staff may be motivated to use technology and, in turn, motivate the students. This may in time, lead to increased research output, and thereby “creating databases for future research.”

The sub-heading ‘Target group/ suitability/competencies/attitudes’, was populated by comments from only the Critic. These ranged from concerns regarding the computer literacy of students, that “some students may be left behind”, to “differences in cultural convictions, moral norms, and political affiliations” that may create unexpected problems. The equality of interactions “if some students cannot participate due to data issues” was also mentioned. Other negative thoughts were expressed regarding extra workload for students, especially for those who are “uninspired and lazy”, and that students would not buy into it if it is not done perfectly. One participant mentioned the implications of the Popi2 act and how we could be sure that students’ data would be protected.

The Change Processes

Main theme two had six sub-themes. Considering the sub-theme ‘Lecturer professionalism’, participants engaging in the Critic role noticed that lecturers may be offended at being prescribed to and that the added workload of developing new content would foster negativity. The only comment from the Dreamer was that lecturers “should have experience in their field, not only academic.”

‘Organizational management’ was populated by comments from only the Dreamer role and all with the same premise, i.e. information dissemination. This was embodied in the viewpoints that follow. The decision to implement seamless learning had to be communicated to all staff members and students, including elucidating the benefits, why it had to be implemented, and how it would be done. It could also be part of the marketing strategy for prospective students – selling the innovative approach of academic ventures at the university. It was observed that the “process and ideas guiding seamless learning are already part of learning strategies in modules presented” and that “successful experiential learning strategies” were already in place at the institution. These practices could guide the creation of a directory document or university policy set out by the already established CTL.

As with any new endeavor, it is important to focus on ‘Evaluation and quality control’. The Realists focused on rewards, and specifically that lecturers “who effectively implement seamless learning in the modules, should be recognized and rewarded.” They felt that it had to form part of the criteria for the promotion. Interesting enough, the Dreamers concentrated on the assessment of seamless learning. They held the conviction that different types of assessment methods had to be explored in order to complement different methods of learning. Assessment should not be time-bound, and students had to be challenged “in other ways than formal assessment only.”

With change come ‘Changing roles and responsibilities’ and ‘Change of models, methods and approaches’. If we look at the former, comments from the Dreamer dominated this sub-theme. It is intriguing that they only articulated opinions regarding the learner and not the lecturers as well. They affirmed that seamless learning would “stimulate and inspire”, “encourage self-regulated learning”, “challenge students”, and “develop happy learners.” It would also accommodate learners with disabilities and those with “different learning styles.” It was further postulated that the students would work “actively by using the body and senses.” One comment from a Critic was to “work with lecturers who are interested to maintain their buy-in.”

Moving on to ‘Change in methods and approaches’, comments from all three roles were overwhelming. These could be divided into content, presentation, and the student. It was asserted that adopting the process would imply curriculum changes, but that the nature of some disciplines did not lend itself to seamless learning models. It is thus impractical to make it compulsory for all modules; “In courses that are theory-based it may not be conducive to the entrenchment of basic knowledge.” Regarding presentation, “Lecturers across all faculties need to understand what seamless learning is – a repeated framework must be distributed.” It was seen as imperative that literature be consulted, and dedicated research be done to “monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of seamless learning and the relationship with student success.” Focusing on the student, the assumption was that students could not start their careers when they had to be retrained at the workplace, so they had to be given the opportunity to learn from experience.

The Design and Implementation Process

Although the sub-heading ‘Technology’ was also part of the first theme, ‘Decision process’, it was important to add it to the design and implementation process since it formed the backbone of seamless learning. There were no comments from the Critic that fit into this sub-theme. It was overshadowed by the other two roles whose comments boiled down to two aspects, i.e. hardware and software. In order for seamless learning to be successfully implemented at our university, the participants were of the opinion that all students had to be issued with wireless handheld devices and have “access to state-of-the-art technology.” Partnerships with interested parties from the technology industry could be established in order to get better deals. It was also suggested that the devices stay the property of the university, to be returned or redeemed on the day of graduation. A few problems were anticipated, such as insurance on the devices, theft and breach of contract. With reference to software, meaningful suggestions were made such as developing apps for seamless learning that could be linked to the University communication channel, tracking practical hours spent on a subject, as well as the opportunity for reflective writing, downloaded to the cloud. Electronic data capture was seen as the ultimate goal.

Reminiscing about the second sub-theme, ‘Guidance/ support/degree of autonomy of learners’, the Realists made the most applicable comments. They believed that top management (including the Deans of Faculties), had to be part of it so that there was a top to bottom approach. It was seen as a given that there had to be a “sufficient number of support staff who need to train and support lecturers”, which included support structure and systems, ICT support services, and a call center. The participants were quite optimistic in stating that “Fortunately, we have all the support we need to make this work.” They were talking about our state-of-the-art CTL, knowledgeable academic facilitators, and Teaching and Learning managers assigned to each Faculty. The Dreamers assumed that “all lecturers will be given excellent training in adapting seamless learning.”

The participants adopting the role of the Critic took precedence over the other roles when it came to ‘Lecturer professionalism’. Gloomy predictions such as “lecturer overload”, lack of “time to develop extra material”, especially in certain modules, and that “lecturers might be offended at being prescribed [to]” were heard. It was also foreseen that “not all lecturers will engage in the same way.”

‘Social learning participation and involvement of network/various social practices’ is a sub-theme that elicited numerous comments. The most important aspect that crystalized was that seamless learning content developers/lecturers had to “talk to the industry.” They had to partner with experts and draw on their experience in order not to “rediscover the wheel.” The students also had to be able to interact with experts and thereby ‘experience the world’ by being “exposed to real-life content earlier to improve their contacts and employability.” Benefits of social learning participation were seen as that students could “communicate with one another and their lecturer outside the class”, flow could be taught through experience, and they could experience real-world scenarios. It would even be possible to be in direct contact with the lectures during practical work through a video app or receive immediate feedback (writing reports on the cloud which the lecturers could assess immediately).

When considering ‘Learning objectives and learning results’, participants who had the Dreamer role had the most to say and, interestingly enough, no comments were made by the Critic in this instance. The theme could be divided into a method of application, benefits and innovation. “Students must be given the opportunity to learn with all their senses” and apply the knowledge through experiential learning. This was done by “doing practical activities and note-taking on electronic devices, guided by specific prompts” and therefore “resist word for word learning.” The benefits of seamless learning were praised. This was also a sign that the group of participants felt optimistic and positive about the prospect. I will only name a few of the many comments that could easily fit into this sub-theme; “Better contextual knowledge and retention of material”, “enhanced critical thinking and reasoning skills”, “improved interpersonal social learning”, “stimulating creativity and innovation”, “unbiased learning environment”, and encouraging “collaborative learning and social constructionism”. Where innovation came into play was where new ideas were created, and standards resisted – a sort of “education innovation.” So it was believed that the world is changed by example.

The last sub-theme of the Design and implementation process was ‘Assessment formative and summative, evaluation and testing’. The Realists contributed the following; “Set baseline of students’ performance before implementation”, and “monitor student usage/ feedback during implementation.” Class tests could be completed on the mobile device. In order for this to succeed, the assessment policy had to be improved.

Reflection

When looking back on this project, one thing stood out, and that was the enthusiasm and positivity of the participants. They were all so eager to implement seamless learning, and when informally conversing with them, it was almost overwhelming to experience their positive attitudes. Unfortunately, there may be certain obstacles to overcome. Some are universal and others more specific to South Africa, because, as a developing country, we have certain unique challenges.

The high crime rate in South Africa (2.01 million crimes were reported in 2019 (Writer, 2019), makes device theft a high probability. Accessibility to physical resources, as well as transport problems and costs, are very real challenges. Link that to the limited access to Wi-Fi in public areas, as well as the high cost of data which is unaffordable by the average student on campus (see also technology access earlier in the chapter), are all challenges to be considered. The high number of students in the classes (with up to a thousand registered students), the issue of control, and added pressure on the already overloaded university servers, are also hindrances in the South African context.

Other aspects of concern (which are more universal) are negative attitudes of lecturers and students; some lecturers are set in their ways, and not all will embrace new teaching approaches; the additional workload; lack of computer literacy skills (relevant for lecturers and students); re-designing of modules; and an unchanging assessment strategy. Lack of policies (nationally and institutionally), as well as the absence of informative, instructional guides, may also stand in the way of success. And then there is the problem that not all types of modules lend themselves to the implementation of a seamless learning approach.

Looking at the benefits of seamless learning, a number of factors count in favour of the approach. Firstly, the students are no longer class -and textbook bound. This means that students can receive more practical experience as seamless learning encourages them to be exposed to real-life situations. This can mean that increased contact with experts in the field of study could improve their chance to be employed. Seamless learning also motivates critical thinking and encourages self-regulated learning as well as challenging students not to solely rely on the knowledge from textbooks. In other words, they learn with all their senses. This approach also accommodates learners with different learning preferences. Another benefit is that they are in direct contact with their lecturers and communication continues both with fellow students and the lecturer outside the class environment.

In order for the seamless learning approach to work, the following aspects crystalized from the analysis of the data and can guide the lecturer in applying seamless learning in the higher education environment:

- The lecturers and students need a positive attitude.

- There must be contact with experts.

- Sufficient training for both staff and students.

- Accessible, stable, free Wi-Fi.

- Availability of handheld devices for those who do not have access to it.

- Good assessment strategies.

- Comprehensive policies (national and institutional).

- Good communication between all the relevant parties.

- Sufficient support staff and structure for both the lecturers and students.

- It cannot be made compulsory because not all modules lend themselves to this kind of approach.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be said that seamless learning is not only a viable option but also an essential option, especially if we want to take educational innovation to the next level. The benefits far outweigh the challenges, and if the lecturers and students can get on board, a multitude of possibilities await. A way forward for this study is to do research regarding implementation strategies in order to move adoption and implementation of mobile seamless learning to broader and sustainable levels.

Footnotes

1 Most of these articles’ focus on open and distance learning.

2 “The Protection of Personal Information Act is commonly referred to as POPI. The purpose of the Act is to ensure all South African businesses conduct themselves in a responsible manner when collecting, processing, storing and sharing another entity’s personal information by holding them accountable should they abuse or compromise the third party’s personal information in any way” (Landsberg, 2016).

References

Assan, T. & Thomas, R. (2012). Information and communication technology Integration into teaching and learning: Opportunities and challenges for commerce educators in South Africa. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology, 8(2), 4-16.

Basitere, M. & Ivala, E. N. (2017). Implementation of Blended Learning: The experiences of Students in the Chemical Engineering Extended Curriculum Program Physics Course. Conference proceedings of the International Conference on e-Learning. (pp. 23-30).

Basitere, M., & Eunice, N. (2017). An exploration of students’ experiences of Blended Learning in a physics course at a university of technology. Journal of Social Development in Africa January 2017, 32(1), 23-43.

Bati, T.B., Gelderblom, H. & Van Biljon, J. (2014). A blended learning approach for teaching computer programming: design for large classes in Sub-Saharan Africa. Computer Science Education March 24(1), 71-99.

Bereiter, C. & Scardamalia, M. (2005). Beyond Bloom’s taxonomy: Rethinking knowledge for the knowledge age. Fundamental Change, 5–22.

Blackboard. (2018). What is Blackboard Learn. https://help.blackboard.com/

Bottomley, E. (2020). SA has some of Africa’s most expensive data, a new report says – but it is better for the rich. Business Insider South Africa. https://www.businessinsider.co.za/how-sas-data-prices-compare-with-the-rest-of-the-world-2020-5

Burnard, P., Gill P., Stewart K., Treasure E & Chadwick B. (2008). Analyzing and presenting qualitative data. BDJ 204, 429–432. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.292

Chan, T., Roschelle, J. Hsi, S. Kinshuk, K & Sharples M. (2006). One-to-one-technology-enhanced learning: an opportunity for global research collaboration. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, World Scientific Publishing, 1(1), 3-29.

Cloete, N., Dinesh,N., Hazou, R. T. & Matchett, S. (2015). E(Lab)orating performance: transnationalism and blended learning in the theatre classroom. Research in Drama Education, 20(4), 470-482.

Council for Higher Education (CHE). (2014). Distance Higher Education Programmes in a Digital Era: Good Practice Guide. CHE.

Council for Higher Education (CHE). (2014). Distance Higher Education Programmes in a Digital Age: Programme Accreditation Criteria. CHE.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. SAGE.

Department of Higher Education and Training. (2014). Policy for the Provision of Distance Education in South African Universities in the Context of an Integrated Post-school System. Government Gazette No 37811, 7 July 2014, No 535. DHE.

Elmansy, R. (2015). Disney’s Creative Strategy: The Dreamer, The Realist and The Critic. https://www.designorate.com/disneys-creative-strategy/

Fressen, J. W. (2018). Embracing distance education in a blended learning model: challenges and prospects. Distance Education, 39(2), 224-240.

Gillwald, A., Moyo, M. & Stork, C. (2012). Understanding what is happening in ICT in South Africa: A supply- and demand side analysis of the ICT sector. (Research ICT Africa policy paper 7, 2012). International Development Research Centre. https://www.researchictafrica.net/publications/Evidence_for_ICT_Policy_Action/Policy_PaChapter_7_-_Understanding_what_is_happening_in_ICT_in_South_Africa.pdf

Hiralaal, A. (2012). Students’ Experiences of Blended Learning in Accounting Education at the Durban University of Technology. South African Journal of Higher Education, 26(2), 316-328.

Kemp, S. (2020). Digital 2020: South Africa. Datareportal. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-south-africa

Kleinveldt, L., Schutte, M. & Stilwell, C. (2016). Embedded librarianship and Blackboard usage to manage knowledge and support blended learning at a South African University of Technology. South Aftrican Journal of libraries and information science 82(1). https://sajlis.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/1592/0

Laaser, W. (2006). Virtual universities for African and Arab countries. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 7(4). http://tojde.anadolu.edu.tr/tojde24/index.htm

Landsberg, T. (2016). What is POPI? SEESA. http://www.seesa.co.za/what-is-popi/

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. (Pea, R. & Brown, J.S. (Eds.). Learning in doing, 95. Doi:10.2307/2804509.

Lazem, S. (2019). On Designing Blended Learning Environments for Resource-Challenged Communities. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v14i12.10320

Lichtman, M. (2013). Qualitative research in education: A user’s guide (3rd ed.). SAGE.

McGuinness, M. (2009). The Secret of Walt Disney’s Creativity. https://lateralaction.com/articles/walt-disney/

Meintjies, A. (2018) (a). Digital Identity of staff at the UFS. 2018. UFS Centre for teaching and learning.

Meintjies, A. (2018) (b). Digital Identity of students at the UFS. UFS Centre for teaching and learning.

Meintjies, A. (2019). Guidelines for blended learning at the UFS. UFS Centre for teaching and learning.

Mertler, C. A. (2012). Action research: improving schools and empowering educators (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Nel, E. (2005). Creating meaningful blended learning experiences in a South African higher education classroom: an action inquiry. [Doctoral thesis]. University of the Free State. http://scholar.ufs.ac.za:8080/xmlui/handle/11660/1214

Ogbonnaya, U.I. (2010). Improving the teaching and learning of parabolic functions by the use of information and communication technology (ICT). African Journal of Research in mathematics, science and technology education, 14(1), 49-60.

Pillay, R., & Gerrard, P. (2011). Implementing a ‘blended learning approach’ in a social work course: the perceptions of first-year students at a South African university. Social Work, 47(4), 497-510.

Prinsloo, P. & Van Rooyen, A. A. (2007). Exploring a blended learning approach to improving student success in the teaching of second year accounting. Meditari, 15(1), 51-59.

Rusman, E., Tan, E., & Firssova, O. (2018). Dreams, realism and critics of stakeholders on implementing and adopting mobile Seamless Learning Scenario’s in Dutch Secondary education. In Parsons, D., Power, R., Palalas, A., Hambrock, H., Mac Callum, K., (Eds), Proceedings of the 17th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, 11-14 November 2018, Chicago, IL, USA (pp. 88-96). https://www.learntechlib.org/p/184927/

Ruth, A. (2017). Applying UNESCO Guidelines on Mobile Learning in the South African Context: Creating an Enabling Environment through Policy. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(7), 24-44.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (1999). Schools as knowledge- building organizations. In D. Keating & C. Hertzman (Eds.), Today’s children, tomorrow’s society: The developmental Health and Wealth of Nations (pp. 274-289). Guilford.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2006). Knowledge Building: Theory, Pedagogy, and Technology. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of: The learning sciences (pp. 97–115). Cambridge University Press.

Sharples, M., McAndrew,P., Weller, M., Ferguson, R., FitzGerald, E., Hirst, T., Mor Y., Gaved, M. & Whitelock, D. (2012). Innovating Pedagogy 2012: Open University Innovation Report 1. The Open University.

Siyabona Africa. (2020). Introduction to South Africa. [Web page]. http://www.siyabona.com/introduction-south-africa.html

Stats SA. (2020). Protecting South Africa’s elderly. [Web page]. http://www.statssa.gov.za/?p=13445

Tamukong, J. A. (2007). Analysis of information and communication technology policies in Africa. PanAf Edu Newsletter, 1(1), p. 4. http://www.ernwaca.org/panaf/IMG/pdf/panaf-newsletter-EN.pdf

Thomas, G. (2017). How to do a research project: A guide for students. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). SAGE.

Tshuma, N. (2012). Blended Learning Model: Development and Implementation in a Computer Skills Course. South African Journal of Higher Education, 26(1), 24-35, (EJ989924).

Tshabalala, M., Ndeya-Ndereya, C. & Van der Merwe, T. (2014). Implementing Blended Learning at a Developing University: Obstacles in the way” The Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 12(1), 101-110. www.ejel.org

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO). (2011). UNESCO mobile learning week report. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/ED/ICT/pdf/UNESCO%20MLW%20report%20final%2019jan.pdf

Uosaki, N., Ogata, H., Li, M., Hou, B. & Mouri, K. (2013). Guidelines on Implementing Successful Seamless Learning Environments. A Practitioners’ Perspective. iJIM, 2(2), 44-53.

Vaughan, N., Reali, A., Stenbom, S., Van Vuuren, M. K. & MacDonald, D. (2017). Blended learning from design to evaluation: International case studies of evidence-based practice. Online Learning, 21(3), 103-114. Doi: 10.24059/olj.v21i3.1252.

Westera, W. (2011). On the Changing Nature of Learning Context: Anticipating the Virtual Extensions of the World. Educational Technology & Society, 14(2), 201–212.

Wong, L. H. (2015). A Brief History of Mobile Seamless Learning. In Wong, L.-H., Milrad, M., & Specht, M. (Eds.), Seamless Learning in the Age of Mobile Connectivity, (pp. 3-40). Springer.

Wong, L. H. & Looi, C. K. (2011). What seams do we remove in mobile-assisted seamless learning? A critical review of the literature. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2364–2381.

Wong, L. H., Chai, C. S., Aw, G. P., & King, R. B. (2015). Enculturating seamless language learning through artifact creation and social interaction process. Interactive Learning Environments, 23(2), 130–157. https://doi-org.ezproxy.elib10.ub.unimaas.nl/10.1080/10494820.2015.1016534

Writer, S. (2019). South Africa crime state 2019: everything you need to know. BusinessTech. https://businesstech.co.za/news/government/340513/south-africa-crime-stats-2019-everything-you-need-to-know/

Addendum 5.1: South Africa

The Critic

Table 5.5: The Critic

| 1. THE STUDENT | |

| Physical aspects | Health and safety risks on excursions.

Access to resources. Transport |

| Psychological aspects | In some modules, differences in cultural convictions, moral norms, and political affiliations may create unexpected problems.

Some students may be left behind. |

| Practical aspects | Extra workload for students (when they are already overworked).

Equality of interactions/learning (if some students cannot participate due to data issues). Computer literacy of students. Uninspired and lacy students. |

| 2. THE LECTURER | |

| Negative attitude | Lecturers might be offended at being prescribed.

Not all lectures will engage in the same way. |

| Lack of knowledge | There may be lectures unable/unqualified/uncomfortable at having to incorporate Seamless learning.

All lecturers are not tech-savvy. |

| Workload | Lecturer workload (where will they find time to develop extra content).

A lot of extra work for some lectures depending on the type of module. |

| 3. ACADEMIC IMPLEMENTATION | |

| Specific challenges | The base knowledge level of students differs widely.

Class sizes will make it challenging. Faculty specific needs. Difficult to assess knowledge accurately. |

| Curriculum | Yet more curriculum changes.

Impractical to make it compulsory for all modules. In courses that are theory-based it may not be conducive to entrenchment of basic knowledge. |

| Negative aspects of Seamless learning | Time consuming.

Limit academic freedom. Some knowledge can only be acquired in more traditional ways because it is abstract. |

| 4. TECHNOLOGY HINDRANCES | |

| Data/Wi-Fi | Data and technological challenges may demotivate learners and lecturers.

Data costs and connectivity issues. Wi-Fi accessibility from institute. |

| Hardware | Access to technology.

Technology not ready (data, cost). Limitations of funding to use the latest technology. Stolen devices (unable to prepare for certain assessments). |

| Support | ICT support and infrastructure can be a problem.

Can the university’s servers handle the strain with an online blended approach? Infrastructure prerequisites. |

The Realist

Table 5.6: The Realist

| 1. TRAINING | |

| Lecturers | Lecturers need to understand what good practice entails – a document and resources must be made available.

Lecturers must be trained by experts in both teaching and learning. Effective use of the apps/technology required. |

| Students | Explain why/how/benefits.

Students must be trained to use the appropriate technology required in Seamless learning |

| 2. CONTENT | |

| Experts | Enable students to contact and interact with experts.

Encourage staff to partner with different experts in the industry Talk to other persons with experience – do not rediscover the wheel. Draw on the experience of others. |

| Policy | Improve assessment policy.

A guiding document or policy can be set by gathering already successful experiential learning strategies. The process and ideas guiding Seamless learning are already part of learning strategies in modules presented. |

| Curriculum | Re-curriculate the modules.

Instructional design. The nature of some disciplines lends itself well to blended learning models. Dedicated research must be done to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of Seamless Learning and the relationship with student success. Use interactive classes where students present the classes under supervision of the lecturer. |

| 3. IMPLEMENTATION | |

| Communication | Communicate the decision to all staff and students.

Explain benefits/why/how Market this innovative approach/ capability (new students’ recruitment). |

| Lecturers | Lecturers who effectively implement Seamless learning in the modules should be recognised and rewarded.

Promotion. |

| Measure & monitor | Measure students’ performance after relevant time – compare with baseline.

Monitor student usage/feedback during implementation. Set baseline of students’ performance before implementation. |

| Support | Commitment from top to bottom.

Top management must be part of it Sufficient number of support staff who need to train and support lecturers Integrated Computer Technology support services Call centre Academic facilitators |

| 4. TECHNOLOGY | |

| Hardware | Procure all equipment (wireless handheld devices).

Partner with the tech industry – best deal on handheld devices. Insurance on handheld devices. If it is the university’s property and students use and return them on graduation day or buy it from the university. |

| Software | Apps for Seamless learning can be linked to the university’s systems.

App that keeps track of your practical hours spent on a subject. |

| Data & Wi-Fi | We need to ensure that we have ubiquitous Wi-Fi on campus that both staff and students can access.

The Wi-Fi speed should be sufficient across campus. Wi-Fi hotspot for offline download. |

The Dreamer

Table 5.7: The Dreamer

| 1. ADVANTAGES of SEAMLESS LEARNING | |

| The student in the centre | Challenge students.

Everyone will be stimulated and inspired. Seamless learning will encourage self-regulated learning. Seamless learning apps will accommodate learners’ different learning styles. |

| Content | Better contextual knowledge and retention of material.

Unbiased learning environment. Seamless learning will stimulate creativity and innovation. Seamless learning will enhance critical thinking and reasoning skills Seamless learning will encourage collaborative learning and social constructionism |

| Flow of learning | Students can communicate with one another and their lecturer outside the class.

Immediate feedback. Students who are doing clinical/practical work in direct contact with lecturers using technology. Experience real world scenarios. Resist word for word learning Doing practical activities and note taking on electronic devices; guided by specific prompts. |

| Better future for students | Every student should be exposed to the reality of his future work and not just study from a textbook.

Through seamless learning students will be better equipped for life after graduation. Will create better employers. Practical experience. |

| Social aspects | Improve interpersonal social learning.

Contributing to the community. Change the world by example. Less political, racial and gender issues. |

| The lecturer | Increased research output and publications.

Creating databases for future research. Creation of more jobs to cover clinical work. |

| 2. PREREQUISITES FOR SEAMLESS LEARNING | |

| LECTURERS | Characteristics

Be fair to all. Motivate all learners. All staff motivated to use technology in teaching students.

Content It must be accessed continuously and not time bound. Include authentic contexts. Students must be given the opportunity to learn from experience. Different types of assessment methods must be explored to compliment different methods of learning. Students must be challenged in other ways than formal assessment only.

Preparation All lecturers will be given excellent training in adapting seamless learning. Virtual trainers. |

| STUDENTS | Students are motivated to use technology.

Must be able to apply knowledge. Students must be given the opportunity to learn with all their senses. |

| TECHNOLOGY | Access and Data

Stable Wi-Fi networks. Every student must be given access to online learning. Unlimited data and free technology There will be a dedicated 24-hour help line centre to resolve technical difficulties.

Hardware Access to state-of-the-art technology and equipment. All students have a tablet/smart phone. App for reflective writing – downloaded to the cloud. Free technology. |

Decision Processes

Table 5.8: The Decision process

| Category/factor | Freq | % | Example statements |

| Benefits/surplus/value/results | 4 | 2 | Every student should be exposed to the reality of his future work and not just study from a textbook.

Practical experience. |

| Costs/efforts/investment/dangers | 22 | 12 | Access to technology.

Data costs and connectivity issues. Time consuming. Some knowledge can only be acquired in more traditional ways because it is abstract. Class sizes will make it challenging. Computer literacy of lecturers. Access to resources. Transport a problem. |

| Technology | 16 | 9 | Data for students.

Wi-Fi hotspot for offline download. ICT support and infrastructure. Data and technological challenges may demotivate learners and lecturers. Stable Wi-Fi networks Every student must be given access to online learning. |

| Teachers’ Competencies/ attitudes | 12 | 7 | Lecturers must be trained in effective use of the apps/technology required.

Workshops. Increased research output and publications Creating databases for future research All staff motivated to use technology in teaching students. |

| Target group/suitability/competencies/attitudes | 9 | 5 | Lecturers need to understand what good practice entails.

Extra workload for students. Students won’t buy in if not done perfectly. Computer literacy of students. In some modules, differences in cultural convictions, moral norms, and politics. Affiliations may create unexpected problems. |

| Social expectancies/ role requirements | 1 | 1 | Can students start careers without retraining at the workplace? |

| National education/curriculum | 3 | 2 | Yet more curriculum changes.

Re-curriculum of all the courses. |

| Subtotal | 67 | 37 |

Change Processes

Table 5.9: The Change process

| Category/factor | Freq | % | Example statements |

| Teacher professionalism | 4 | 2 | A lot of extra work for some lectures depending on the type of module.

Lecturers might be offended at begin prescribed Not all lectures will engage in the same way. |

| Organizational management | 8 | 4 | Explain benefits/why/how.

Communicate the decision to all current students and staff. A guiding document or policy can be set by gathering already successful experiential learning strategies. |

| Evaluation and quality control | 6 | 3 | Lecturers who effectively implement SL in the modules should be recognised and rewarded.

It must be accessed continuously and not time bound. Different types of assessment methods must be explored to compliment different methods of learning. Students must be challenged in other ways than formal assessment only. |

| Changing roles and responsibilities | 9 | 5 | Everyone will be stimulated and inspired.

Seamless learning will encourage self-regulated learning. Seamless apps will accommodate learners’ different learning styles. Seamless apps will accommodate students with disabilities. |

| Change of daily school organization | 4 | 2 | Lecturers across all faculties need to understand what Seamless learning is – a repeat framework must be distributed.

Use interactive classes where students present the classes under supervision of the lecturer. |

| Change of models, methods and approaches | 5 | 3 | Not applicable to all modules.

Impractical to make it compulsory for all modules. The nature of some disciplines lends itself well to blended learning models |

| Subtotal | 36 | 20 |

Design and Implementation Processes

Table 5.10: The Design and Implementation process

| Category/factor | Freq | % | Example statements |

| Technology | 15 | 8 | Apps that keep track of your practical hours spent on a subject.

Partner with the tech industry – best deal on handheld devices. If it is the university’s property and students return on graduation day or buy it from university. Access to state-of-the-art technology and equipment. All students have a tablet/ smartphone Free technology. |

| Guidance/support/ degree of autonomy of learners | 15 | 8 | Commitment from top to bottom.

Set up and provide support structure for staff implementation. Integrated Computer Technology support services. Call centre. Teaching & Learning managers. Academic facilitators. All lecturers will be given excellent training in adapting seamless learning. |

| Social learning participation and involvement of network / various social practices | 19 | 10 | Talk to the industry.

Enable students to contact and interact with experts Encourage staff to partner with different experts in the industry. Draw on other experiences. Students can communicate with one another and their lecturer outside the class. Immediate feedback. Experience real world scenarios. Experience the world. Students can be exposed to real life content. |

| Learning objectives and learning results | 23 | 13 | Students must be trained to use the appropriate technology required in SL.

Better contextual knowledge and retention of material. Experiential learning. Seamless learning will stimulate creativity and innovation. Seamless learning will enhance critical thinking and reasoning skills. Seamless learning will encourage collaborative learning and social constructionism. Must be able to apply knowledge Students must be given the opportunity to learn with all their senses. |

| Assessment formative and summative, evaluation and testing | 4 | 2 | Monitor student usage/feedback during implementation.

Set baseline of students’ performance before implementation. Improve assessment policy. |

| Process-oriented design of interdisciplinary / transboundary activities | 5 | 3 | Work actively by using the body and senses.

Include authentic contexts. Students must be given the opportunity to learn from experience.

|

| Experiential design of activities within school and in out-of-school environments/ settings | 0 | 0 | |

| Safety-measures/

Insurance |

0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 81 | 44 | |

| Total | 184 | 100 |