Helga Hambrock

Introduction

Seamless learning is a buzz word that has lately received substantial attention in the field of educational technology, but how known is the concept for educators in the USA? In order to shed light on this topic, this study firstly focuses on the historical development of the concept “seamless learning” as used in the USA. Secondly it aims to establish to answer the imminent question: “What are the perspectives of educators about seamless learning in the context of higher education in the USA?”

The Historical Development of the Term “Seamless Learning” in the USA

The use of the term “seamless learning” within the higher education environment in the USA, can be traced back to 1991. The term points to a “new commitment to holistic student education” where the author, L. Lee Knefelkamp, calls on academic and student affairs professionals to work together to create “The Seamless Curriculum”. The aim of the notion was to provide a holistic student education and “urges joint action on multiculturalism and diversity, experiential and service learning, assessment, campus athletics, and the graduate education” (Knefelkamp, 1991).

The term “seamless learning” was again mentioned by the American College Personnel Association in 1996 and was elucidated as “distinct separated learning environments” that are part of “one continuous learning experience” (Kuh, 1996). George Kuh distinguished six seamless learning environments:

- in or out-of-class learning,

- academic or non-academic learning,

- curricular or non-curricular learning,

- on- and off-campus experiences,

- formal or informal learning, as well as

- learning with or without technology.

The motivation for using a seamless learning approach was further explained by Kuh (1996) as

generating enthusiasm for institutional renewal; creating a common vision for learning; developing a common language; fostering collaboration and cross-functional dialogue; examining the influence of student cultures on student learning; and focusing on systemic change.

His forward-thinking approach was not quite understood at the time, but as technology evolved over the years, many examples of seamless learning environments can be found in literature.

Before the term was developed, seamless classroom practices can already be identified in Seymore Papert’s article on information technology in education (1987, p.22-30). For this study the students used their books for homework and during class time they used computers. In the eighties, books were mobile and the computers were static. In 1995 the WorldWide Web and the first Learning Management system (WebCT) was introduced to Education in the USA. Email, video, and a variety of digital media were also made available to teachers and students during the nineties. The new technology enabled two-way communication between teachers and students as well as students and their peers anywhere, and at any time. These were the first steps towards a seamless learning experience between several learning environments. Technology enabled students to access the educational material during and after school time (Myers, 1998). However, at that time most educators were not aware of the significance of seamless learning and were rather concerned and often fearful and considering it as “taking a risk” when integrating technology into classrooms: “learning in new ways, especially when using technology of continuing to take risks even when those risks produce results that are unsatisfactory in some way” (Galin & Latchaw, 1998).

At the turn of the 21st century the increased use of Information Communication Technology (ICT) in education led to the birth of STEM programs including Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics in the USA. This was also the time when the development of mobile technologies (including laptops, cellphones and ipads) took seamless learning to the next level as student access to satellite data no longer required the devices to be ‘plugged in’. Technology became more sophisticated, more user-friendly, and information could be accessed at any time with mobile technology. Books, as well as technology became mobile.

In the past ten years more seamless teaching and learning environments evolved as accessibility to -and affordability of virtual reality expanded. Google cardboard and mobile apps as well as artificial intelligence devices as Siri, Alexa and Google Dot, improved. Since 2016 one-on-one devices have been provided to students from primary to secondary education in 50 states in the USA in the form of ipads and google chrome books. The one-on-one device provision increased from 55% in 2016 to 88% in 2018 (Graafland, 2018).

In 2016 a National ECAR survey was conducted in the USA. The objective of the survey was to establish the availability of information technology to university students in the United States. It was found that ownership of laptops, smartphones and tablets by students is growing close to market saturation. “96% of students own smartphones, 93% own laptops and 57% own tablets. The survey reveals that students have access to multiple devices with just over half (52%) of the students owning all three of the aforementioned devices, while conversely only 1% own none of these three devices. The most common combination of device ownership is a laptop and a smartphone (38%)” (Brooks & Pomerantz, 2017, p. 3).

These results indicate that especially mobile technology is currently an essential part of student life in the USA. Besides that every student has access to the internet via mobile devices and thereby having access to information “on the go”. Access can also be understood to be a positive indicator of the student’s interest and ability to use mobile devices. These noticeable high percentages of device ownership can also be interpreted as encouragement for educators to implement the affordances of readily available mobile technology in and outside their classrooms. However, many educators are still reluctant and fearful of using mobile technology to enhance their teaching (Lam 2000; O’bannon, & Thomas 2014; Ertmer et.al 2012).

To support technology integration in education, the first International Standards of Technology in Education (ISTE) was released in 1998 under the name of National Educational Technology Standards (NETS). The standards include requirements for teaching and learning with technology and emphasize creative innovation, communication skills, and collaborative work projects, with focus on critical thinking, problem-solving, decision-making, and acquiring 21st-century digital citizenship skills (ISTE, 2007).

Even though it may seem that educators are supporting the ISTE technology standards and are aware of the evolving technology, adoption problems to include technology in their teaching and learning are still evident within the educational systems in the USA. Especially, since technology skills are not a requirement for teacher training and implementation within the curriculum (Dugger, 2013). It has, however, become evident amongst educational researchers and educational leadership that schools and universities need to address the inclusion of technology as an important part of their pedagogical approach. According to Siemens, Gašević and Dawson (2015), the need of implementing effective practices and procedures is most evident in blended, online and seamless learning environments, but needs more attention.

This does not mean that interest in using technology to enhance seamless learning does not exist at all in the USA. Several successful case studies have been conducted in the USA and are discussed in the literature review below.

Literature Review

This literature review includes research studies that have been conducted in the field of seamless learning in the USA thus far. A Google Scholar search and the EBSCO library brought forth a large number of resources in the field of seamless learning. However, on closer investigation most of the studies with specific mentioning of the term “seamless learning” were conducted in Singapore, China, and Europe. The term “seamless learning” has not been used in the USA as frequently.

The most relevant research studies are portrayed in the following review. The review begins by identifying important key concepts and definitions of seamless learning in the USA. Furthermore case studies are presented where seamless learning in the USA is mentioned in a variety of learning environments ranging from libraries to Online and Distance Learning (ODL) universities and other teaching and learning environments.

Thereafter a study by the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) including educators perspectives towards including technology in teaching and learning in the USA is discussed.

The first part of this literature review includes a comparison of Kuh (1996) and de Waard, Keskin and Koutropolou (2014) definitions of Seamless Learning. As mentioned in the introduction, the term, Seamless Learning, was coined in the USA (Kuh, 1996). This definition of Seamless Learning can be applied in a wide range of environments. However, as technology evolved from fixed computers to mobile technology, the concepts were refined to Mobile Seamless Learning (MSL) (de Waard Keskin & Koutropolou, 2014). The key concepts of Seamless and Mobile Seamless Learning, are presented in Table 6.1:

Table 6.1: A comparison between SL and the MSL key concepts

| Seamless Learning (SL)

Kuh (1996) |

Mobile and Seamless Learning (MSL)

de Waard, Keskjn and Koutropolou (2014) |

| ● academic or non-academic learning, | 1. encompassing personal and social learning |

| ● in or out-of-class learning,

|

2. ubiquitous access to learning resources, across time |

| ● academic or non-academic learning, | 3. seamless switching between multiple learning tasks |

| ● curricular or non-curricular learning, | 4. encompassing multiple pedagogical or learning activity models |

| ● on- and off-campus experiences, | 5. across locations |

| ● formal or informal learning, | 6. encompassing formal and informal learning |

| ● learning with or without technology. | 7. encompassing physical and digital worlds |

de Waard, Keskin and Koutropolou, (2014) developed the MSL key concepts based on the original SL concepts. The key concepts were adjusted for a Massive Open Online course (MOOC) environment.

Wong and Looi (2011) also suggested that the term ‘Seamless Learning’ should be replaced with the term, ‘Mobile Seamless Learning’. They came to this conclusion after analyzing 54 articles. They identified the following ten key concepts

- Encompassing formal and informal learning;

- Encompassing personalized and social learning;

- Across time;

- Across locations;

- Ubiquitous knowledge access (a combination of context-aware learning, augmented reality learning, and ubiquitous Internet access);

- Encompassing physical and digital worlds;

- Combined use of multiple device types (including “stable” technologies such as desktop computers, interactive whiteboards);

- Seamless switching between multiple learning tasks (such as data collection + analysis + communication).

- Knowledge synthesis (a combination of prior + new knowledge, multiple levels of thinking skills, and multidisciplinary learning) and

- Encompassing multiple pedagogical or learning activity models (Wong and Looi, 2011).

Although Wong and Looi are both researchers in Singapore, their understanding of seamless learning is of high standing amongst researchers in the USA and Europe (de Waard Keskin & Koutropolou, 2014). Wong (2015), mentions that early studies on seamless learning in the USA centered on ‘systemic-level reforms’ in higher education and did not receive much further attention. Only as technology evolved more studies were conducted in this area.

Now that the terms Seamless learning and Mobile Seamless Learning are clarified in the context of the USA, the relevant research studies in the USA are presented. In 2000, Steven Bell conducted a study on implementing the seamless learning approach in a library by changing the training method for students and researchers from on-site training and traditional lecturer centered teaching to online and out-of-the-classroom training. It meant that asynchronous training could take place at any time. The approach was found to be effective and useful (Bell, 2000). Since then only a few relevant studies were conducted.

One of these research studies is the study: ‘Moving to Seamless Learning: A Framework for Learning Using Multiple Devices’ by Krull and Duart (2017). The study was an investigation at an Open Distance Learning (ODL) University on the perspective of students on learning experience design. The study proposed that, “learning experiences need to be designed that can be facilitated across and between different devices and support the needs of students” (Krull and Duart, 2017). A multi-device framework for learning that explores the intersections between multiple devices, locations and learning activities was applied during the investigation.

It is found that students mostly use devices separately, but sometimes make use of different devices together, either sequentially or simultaneously. Another finding is that educators need to include “both the physical context (location) as well as the intentional context (purpose) of how students make use of different devices for learning” (Krull and Duart, 2017). A framework is proposed that supports “the use of multiple devices for teaching and learning, for both educators and learners to be able to take advantage of flexible and seamless learning” (Krull and Duart, 2017). The study evaluates the location and purpose of the framework with specific focus on the adoption of the framework by educators.

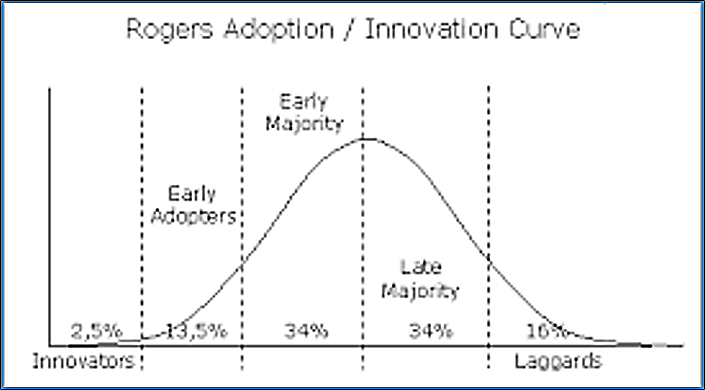

The study reminds us of Roger’s adoption curve. The adoption curve of Rogers explains how new practices or technology are accepted and adopted by people.

The discovery that seamless learning is a ‘rather new and unknown learning approach’ for Higher Ed in the USA and knowledge of the adoption curve of Rogers led to the question how and where the interest of educators to use technology for teaching and learning is. A research study from the EDUCAUSE Center for Analysis and Research (ECAR) provides more information about the approach of educators regarding the implementation of technology in their teaching environment which is also relevant to the implementation of a seamless learning approach.

The research study presents the findings of a survey that was distributed amongst Higher Ed educators. In the study it is found that only a third of educators are including the student’s ability to access their smartphones for classes. These results point to the lack of motivation of educators to use the mobile technology for academic work in the classes, let alone applying seamless learning in their classrooms. (Dahlstrom & Bichsel, 2014). One may assume that a lack of motivation to implement technology into teaching may be due to insufficient training. The table below however provides an overview of the Educational services that are provided by institutions for educators in the United States, as derived from the ECAR study:

Table 6.2: Educational technology services provided by institutions in the United States Service

| Educational technology services provided by institutions in the United States Service | Percentage offered by Institutions |

| Learning (course) management support for faculty | 99% |

| Learning (course) management training for faculty | 99% |

| Faculty individual training in use of educational technology | 99% |

| Faculty group training in use of educational technology | 98% |

| Online learning technology support for faculty | 96% |

| Online learning technology support for students | 95% |

| Instructional technologists to assist faculty and instructional designers with integration of IT into teaching and learning | 95% |

| Instructional designers to help faculty develop courses and course materials | 89% |

| Designated instructional technology center available to all faculty | 82% |

| Faculty teaching/excellence center that provides expertise on IT | 79% |

| Faculty training on incorporating students’ use of mobile devices during class | 74% |

Bearing these percentages in mind it is evident that educators/faculty who were included in the survey were well trained and received excellent support for integrating technology in their classes, but the students at the same institutions indicate that use of their mobile devices in their classes is prohibited. The report argues that faculty need to increase their knowledge about effective uses of technology. Also, that they need to seek assistance from instructional designers to design their courses.

One concern that was mentioned by the educators during the survey was that the mobile devices were distracting the students. Forty-nine percent of faculty indicated that the in-class use of mobile devices was distracting to themselves, and 60% said that the use of mobile devices was distracting to others. These opinions are not without consequence as faculty who agreed that in-class use of technology is distracting are significantly more likely to ban or discourage the use of technology in the classroom. They indicated their concern that students would become too distracted. (Dahlstrom & Bichsel 2014).

A framework for describing seamless learning that was designed by Seow, P., Zhang, B., So, H., Looi, C., & Chen, W. (2008), is used to evaluate four case studies and to identify outcomes and areas for future research by Metcalf, Jackson & Rogers (2015). The case studies are conducted in the following disciplines: STEM education, medical training, corporate orientation, and defense training. Although the disciplines are unique, common positive findings include increased student engagement and satisfaction. Both are goals many educators aim to achieve.

More useful literature includes a guide book about digital tools for seamless learning by Ebner (2016), highlights the value of deeper learning opportunities for students. It highlights the importance of having access to new innovations, relevant pedagogical, theoretical foundations and curriculum development strategies to achieve successful, seamless learning. It is a toolbox for educators, researchers and professionals actively involved in the field of education. The practical approach is useful for educators who have little experience in this field.

Another valuable resource that was reviewed included chapter 24 of the book, ‘Designing seamless learning using role playing experiences’ (Jones, Novak, Luchs & Bennani, 2020). The chapter examines the value of seamless learning by role play with technology to establish the effect of the method and the technology on the intrinsic motivation of the students. The finding was that adding roleplay in a seamless e-learning environment had a positive effect on the intrinsic motivation of the student. To include games and role play should be another point that could be included in the planning process for the future.

As mentioned in the introduction, mobile technology has become more sophisticated, more affordable and more accessible for the educational environments, however the ECAR study indicates that educators are not yet convinced that adding technology and especially mobile technology to their classroom are tools they want to implement in their classroom. This takes us to the next part of the study.

Considering these factors as derived from the literature it will be interesting to see what the educators at a higher institution in the USA say about their understanding. In the following section the research methodology of the study is presented.

Research Methodology

A qualitative research exploratory methodology was followed to obtain a rigorous result. The first part of this section includes a discussion of the (1) Sampling and description of the participants of the study, the second part incorporates (2) The structure of the research, the third part is concerned with (3) The data collection process and the final part includes (4) An overview of the data analysis process.

Purposive sampling was utilized for the study as the researcher wanted to focus on a specific selected target group. The target group consisted of educators (full time or adjunct professors) of two the College of Business and the College of Arts and Sciences at a Higher Education Institution in the USA. Some educators teach online, some teach face to face and some use a blended approach. They were given a free choice to participate in the study and to complete a biographical survey.

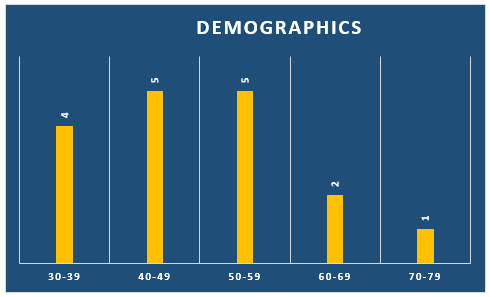

The demographic information of the participants is displayed in Figure 6.2: The majority of participants are between 40 and 59 years old. Remarkably, the “Academic Careers by Country” support this finding by indicating that the average age of professors in the USA is 55.

The Structure of the Research

The research consisted of a three-section workshop including (1) an introduction, (2) a biographical survey and (3) the interactive brainstorming discussion. The concepts were described in a handout and are added as an attachment in Chapter 7.

Two workshops were offered in a blended format to include educators who are teaching on and off-campus too. The workshop was therefore offered in two modes including a video conference mode using Blackboard collaborate and also face to face attendance.

The workshop was offered in three 20-minute sections: The introduction, which included an overview and information session about what seamless learning means and to clarify that all participants are on the same page. The second part was the completion of the biological survey, and the last part was the active workshop.

The workshop was based on the Disney method as described in the preface of this book. The participants were divided into three groups. They were requested to answer specific questions from an assigned perspective. These perspectives included: 1) Realist, 2) Critical thinker, and 3) Dreamer.

Each group had a scribe and one who would read out the questions on a leaflet for their group. The participants brainstormed an answer to the questions and the scribe wrote up the ideas onto post-it papers and stuck them on the whiteboard for all to see. The online participants were participating by expressing their ideas to the groups, verbally. At the end of the last 20-minute session a representative of each group presented their ideas to the participants.

The Data Collection Process

The data was collected from the post-it notes. The information on the post-it notes was captured on an Excel datasheet, and an inductive content analysis was followed to “identify and categorize” (Schamber, 2000) mentioned ideas into themes.

Data Analysis

The post-it notes contained the thoughts and ideas as expressed by the workshop participants and were presented on a whiteboard for all participants to observe.

A set of 125 statements were identified. Two sets of findings were compiled. The Dreamer-Critic-Realist (DCR) set and the Decision-Change-Design and Implementation process (DCDI) set. For both an inductive content analysis was followed.

The frequencies and percentages were calculated as to establish where the main concerns were found. Even though this is a qualitative study the numbers are added to support the most pressing and least important concerns. From the overall data the percentages can be interpreted that the design and implementation process as well as the decision process are more important when it comes to seamless learning whilst the change process may not be as complicated.

Findings

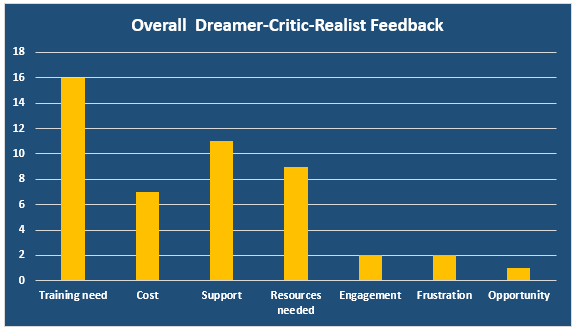

From the Dreamer-Critic-Realist data set the themes that stood out as most relevant are presented here.

The mostly found themes from the realist feedback included:

- the costs,

- overload of information,

- training need for all students as well as faculty,

- support for all.

The critiquers were mostly concerned about

- the costs,

- the training,

- the overload of information,

- concern about support.

In both groups the cost, training and support for students and faculty were found to be crucial.

The dreamers looked beyond the challenges and the ideas that stood out from the rest included:

- enjoying the thought of stepping outside the box,

- offering video classes on a global level and

- sharing knowledge with other classes.

The mostly found themes in all three groups included training need, cost, technology access for all, support for students and the educators, access to resources, student engagement was a positive and frustration a negative observation, only a small percentage mentioned that seamless learning was an opportunity to be explored further.

For the Decision-Change-Design and Implementation process (DCDI) analysis the data were categorized according to the framework of Rusman, Tan and Firssova (2018). Table 6.4 includes the statements relevant to the decision process, Table 6.5 statements relevant to the change process and Table 6.6 the statements relevant to the Design and implementation process. Tables 6.4 to 6.6 are added as Addendum 6.1. This set of data indicated factors affecting the relevant processes at organizational level.

Table 6.3: Frequencies and percentages of suggested factors affecting the decision, change and implementation process

| Category

|

Frequency of statements | Percentage of statements (of total) |

| Decision processes | 46 | 37%

|

| Change process | 30 | 24%

|

| Design and implementation process | 49 | 39%

|

| Total | 125 | 100%

|

A summary of the data are presented in Table 6.3 as categories, frequencies and percentages. According to the overall summary in Table 6.3, it is evident that both the decision process and the design and implementation process are considered to be at the same level of importance, at 37% and 39% respectively. The factors mentioned as most important as part of the design and implementation process included the need of data, implementation of new technologies as VR and GO PRO, the need of clear learning objectives, transboundary activities and again guidance, training and support.

For the change process which includes 24% of the statements, training, support for students, educators and parents are regarded as important. From the DRC and the DCDI approach, the need for training, access to technology and support are indicated as highly important for successful implementation of seamless learning. If these factors were not available the process of using the seamless approach would be frustrating and the interest would diminish.

Reflection and Conclusion

The researcher found that the method used to collect the data to be successful as the participants were motivated and engaged during the workshop.

Considering the question about what the perspectives of educators at higher institutions in the USA on seamless learning are, the findings in Table 3 – 9, portray a wide variety of opinions from various perspectives. Although most participants indicated that a seamless learning approach would be exciting and that students will become more engaged with the content when including more technology in their classrooms, the same percentage of educators thought it could be frustrating to implement the seamless learning approach and that training and support was of uttermost importance.

This finding aligns with the technology adoption curve of Rogers (1996) and can be interpreted that the application of the seamless learning methodology in the higher education environment lies in the 34% late majority of the adoption curve.

This result means that even though the educators at the Higher Education Institutions in the USA have access to technology (as high as 96%), planning and implementation of seamless learning in higher education, needs more attention.

In conclusion the following suggestions and answers to the research question “What are the perspectives of educators about seamless learning in the context of higher education in the USA?” are proposed:

- Educators have not implemented the seamless learning approach in their classrooms. Even though the ISTE standards (International standards for Technology integration in Education) have been accepted by the departments of education and for teachers in schools, educators and especially university professors are still not using the seamless learning approach and need to plan and implement the approach in the near future.

- Educators need more training, support and monitoring when implementing the seamless learning approach in their classrooms. The university is responsible for supporting the implementation process by training and supporting the educators.

- The implementation of seamless learning and technology integration in teaching needs to be aligned to the job appointment and utilized as an incentive to further their career.

This study has opened the door to questions and suggestions towards the implementation of seamless learning by educators at higher education institutions in the USA. It has become evident that successful implementation of seamless learning relies on many role players and factors, however the educator’s knowledge and interest is a crucial driving force behind the result.

References

Bell, S. J. (2000). Creating learning libraries in support of seamless learning cultures. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 6(2), 45-58.

Brooks, D. C., & Pomerantz, J. (2017). ECAR study of undergraduate students and information technology. Research report: Louisville, 4(3), 3.

Dahlstrom, E., & Bichsel, J. (2014). ECAR Study of Undergraduate Students and Information Technology, 2014. Educause.

de Waard, I., Keskin, N., & Koutropoulos, A. (2014). Exploring future seamless learning research strands for massive open online courses. In T. Volkan Yuzer and G. Kurubacak (Eds). Handbook of research on emerging priorities and trends in distance education: Communication, pedagogy, and technology (pp. 201-216). IGI Global.

Dugger, W. (2013). The progression of technology education in the USA. [Paper presentation]. Pacific Rim International Conference on Technology Education, Nanjing, China, 16-18 October 2013.

Ebner, M. (Ed.). (2016). Digital tools for seamless learning. IGI Global.

Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O., Sendurur, E., & Sendurur, P. (2012). Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: A critical relationship. Computers & education, 59(2), 423-435.

Galin, J. R., & Latchaw, J. (1998). The Dialogic Classroom: Teachers Integrating Computer Technology, Pedagogy, and Research. National Council of Teachers of English.

Graafland, J. H. (2018). New technologies and 21st century children: Recent trends and outcomes. OECD Education Working Papers, no. 179.

International Society for Technology in Education. (2007). National educational technology standards for students. ISTE

Jones, S., Novak, K., Luchs, C., & Bennani, F. (2020). Designing Seamless Learning Using Role-Playing Experiences. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Mobile Devices in Education: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice (pp. 392-420). IGI Global.

Knefelkamp, L. L. (1991). The seamless curriculum. CIC Deans Institute: Is this good for our students. Council for Independent Colleges.

Krull, G., & Duart, J. M. (2017). Moving to Seamless Learning: A Framework for Learning Using Multiple Devices. In R. Power, M. Ally, D. Cristol, & A. Palalas (Eds), IAmLearning: Mobilizing and Supporting Educator Practice. International Association for Mobile Learning. https://iamlearning.pressbooks.com/part/ch-5-moving-to-seamless-learning/

Kuh, G. D. (1996). Guiding principles for creating seamless learning environments for undergraduates. Journal of college student development, 37(2), 135-48.

Lam, Y. (2000). Technophilia vs. technophobia: A preliminary look at why second-language teachers do or do not use technology in their classrooms. Canadian Modern Language Review, 56(3), 389-420.

Metcalf, D., Jackson, M., & Rogers, D. (2015). Reflections on Case Studies in Mobile Seamless Learning. In L. H. Wong, M. Milrad, & M. Specht (Eds.), Seamless Learning in the Age of Mobile Connectivity (pp. 109-117). Springer..

Myers, B. A. (1998). A brief history of human computer interaction technology. Interactions, 5(2), 44-54.

O’bannon, B. W., & Thomas, K. (2014). Teacher perceptions of using mobile phones in the classroom: Age matters!. Computers & Education, 74, 15-25.

Papert, S. (1987). Information technology and education: Computer criticism vs. technocentric thinking. Educational researcher, 16(1), 22-30.

Rusman, E., Tan, E., & Firssova, O. (2018). Dreams, realism and critics of stakeholders on implementing Seamless Learning Scenario’s in Dutch Secondary education. In D.

Parsons, R. Power, A. Palalas, H. Hambrock, & K. MacCallum, (Eds), Proceedings of the 17th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, 11-14 November 2018, Chicago, IL, USA., pp. 88-96. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/184927/

Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of Innovations, 4th edition. The Free Press.

Seow, P., Zhang, B., So, H., Looi, C., & Chen, W. (2008). Towards a framework for seamless learning environments. In Proceeding ICLS’08 Proceedings of the 8th international conference on International conference for the learning sciences (Vol. 2, pp. 327–334). International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Siemens, G., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2015). Preparing for the digital university: A review of the history and current state of distance, blended, and online learning. Athabasca University.

Wong, L. H., & Looi, C. K. (2011). What seams do we remove in mobile-assisted seamless learning? A critical review of the literature. Computers & Education, 57(4), 2364-2381.

Wong, L. H. (2015). A brief history of mobile seamless learning. In L. H. Wong, M. Milrad, & M. Specht (Eds.), Seamless learning in the age of mobile connectivity (pp. 3-40). Springer.

Addendum 6.1

Decision Processes

Table 6.4: Considerations and factors affecting decision processes at organizational level

| Considerations and factors affecting decision processes at organizational level | |||

| Category | Freq. | % | Statements |

| Benefits/surplus/value/results | 7 | 6% | ● Remote contact

● Increase communication skills ● Easier for students ● Increased diversity ● Opportunities for students who cannot attend physically ● Geographically disconnected students can connect ● Inclusion of learning preferences |

| Costs/efforts/investment/dangers | 17 | 14% | ● Software and Technology is expensive

● Time consumption ● Line item in budget ● Introduce one course at a time to control time commitment ● May need to be introduced by department or discipline. ● Technology fees ● Distraction ● Cost ● Infrastructure needed ● Participants- both educators and students will need instruction and training to implement the ideas ● What are the costs involved, both in terms of time and money? ● Training of resources ● Since Tech is evolving- need to keep up with it = need more resources ● Financial impact ● Frustration might kill it ● Complications result to not being very organized ● Massive amount of training of deliverers and users |

| Technology | 5 | 4% | ● Tech support needed

● Tech problems ● Back-up plans for power loss and connectivity ● Technology failure ● Concern of tech failures |

| Teachers’ Competencies/attitudes | 7 | 6% | ● Expectations unrealistic

● Support: All including students, parents and educators ● professional development needed ● Prep time increase ● Faculty deficiency in using technology ● Accessibility to information for all ● Pro-active use of technology for learning |

| Target group/suitability/competencies/attitudes | 7 | 6% | ● Digital learning not for all

● Personalized learning can be lonely ● Increased learner engagement ● Student centered ● Involve all stakeholders ● Diversity of modality to be considered ● Training of pedagogical and technological approach for seamless learning |

| Social expectancies/ role requirements | 1 | 1% | ● Societal impact |

| National education/curriculum | 2 | 2% | ● Accelerated curriculum advantages

● AI Curriculum |

| Subtotal | 46 | 37% | |

Change Processes

Table 6.5: Considerations and factors affecting the change process at an organizational level

| Organization of change processes in educational organization | |||

| Category/Factor | Freq. | % | Statements |

| Teacher professionalism | 3 | 2% | ● Hands-on lecturer training

● Implementation training ● Training for deliverers |

| Organizational management | 6 | 5% | ● Plan of action needed

● Ongoing research ● Needs: Technology, Resources, ● Copy right check ● Manage conceptions when conceptualizing ● Significant coordination needed |

| Evaluation and quality control | 0 | 0% | ● |

| Changing roles and responsibilities | 1 | 1% | ● Adopt to change |

| Change of daily school organization | 5 | 4% | ● Presenting material

● Execution of process ● Remote teaching ● Repetition of work ● Access to global method and resources |

| Change of models, methods and approaches | 15 | 12% | ● Remote learning

● Global collaboration with global community ● Teaching and learning beyond walls ● Decrease travel and accommodation cost ● Ubiquitous learning ● Lower absentees ● Creative learning to classroom ● Cross- cultural and inclusive classroom ● virtual International class room ● Acceptance and adaption ● Change management ● Online more access to global interaction and global learning, but signal slow and cuts out ● Virtual setting can be artificial not real life situation- crisis management ● Convincing all to accept value ● Awareness of Tech competency differences |

| Subtotal | 30 | 24% | |

Design and Implementation Processes

Table 6.6: Organization of design and implementation process

| Organization of change processes in educational organization | |||

| Category | Freq. | % | Example statements |

| Technology | 10 | 8% | ● Assignments in writing

● Wi-Fi can be excuse ● Execution can be limited to all ● Technology 1 on 1 for all ● Immediate access ● Rural Connection ● Student Access ● Ongoing availability ● Technology awareness ● Data to convince |

| Guidance / support / degree of autonomy of learners | 11 | 10% | ● Necessary resources

● Students may become negative ● Exploration ● Increased motivation ● Bot for student support ● Bot for teacher support ● Centralized student support and advising ● Training need: Workshops and one on one ● Responsible use ● Easy material access ● Student engagement |

| Social learning participation and involvement of network / various social practices | 5 | 5% | ● Collaboration with students outside classroom

● Collaboration topic with other students ● Interaction ● Expand network ● Need inclusion for students |

| Learning objectives and learning results | 4 | 4% | ● Training for virtual classroom use

● Advances transfer of knowledge ● Initiative for self-learners ● Statement performance |

| Assessment formative and summative, evaluation and testing | 1 | 1% | ● Virtual site visits |

| Process-oriented design of interdisciplinary / transboundary activities | 17 | 17% | ● Feasibility study

● Pros and Cons ● Increased engagement ● No excuse for loafing ● Frustration can kill enthusiasm ● Instructions on processes are needed. ● More focus on people that are not present than on people being present. ● Virtual Site visits ● VR with live lectures ● Live interview ● Remote streaming-go pro ● Practice of concept ● Overload-credit given to lecturers who prepare classes with technology ● Info for all ● Diversity to be included ● Voice for all ● Access 24/7 |

| Safety-measures / insurance | 1 | 1% | Health issues |

| Subtotal | 49 | 39% | |

| Total | 125 | 100% | |