2

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to,

- identify and use seven constituency tests for determining structure

- understand how to interpret constituency tests to expand grammar fragments

- understand the limitations of constituency tests, and what to do with false positives and negatives

The program of generative syntax is to find the set of rules that describes a language (really that describes every language) and that doesn’t describe things that aren’t in a language. In chapter one, we abstracted away from the words themselves to talk about syntactic categories, which allowed us to write descriptive rules about a language. Our English grammar fragment is the following right now.

Grammar fragment for English

SentenceEnglish → Determiner Phrase Verb

Determiner Phrase → Determiner Adjective Noun

Determiner Phrase → Determiner Noun

We are thus able to talk abstractly about what is possible in English syntax. This way of describing language raised two issues, repeated here.

In response to Issue 2, we developed ways to identify syntactic categories: morphology and distribution. Thus, we can now empirically distinguish between parts of speech in any particular language because each part of speech will have specific morphological and distributional properties. I can determine when something is a noun, a verb, an adjective, etc through not only how it looks (morphology) but also where it appears with respect to other words (distribution).

Importantly, we also noticed that group of words also have syntactic categories. When I put happy and mailman together, I get something that distributes like a noun. That is, happy mailman goes in all the same places that mailman goes, like in between determiners and copulas: the happy mailman is… . (Alternatively, the group of words happy mailman doesn’t act like an adjective: it doesn’t do in the places that adjectives go, like in front of a noun: *the happy mailman carpenter.)

We call a string of words that forms a group a constituent. A constituent, by definition, has a syntactic category. This is because a constituent has a syntactic distribution. As I just stated, happy mailman has the distribution of a noun. That is, the entire string of words “acts like” a noun, not an adjective, not a verb, etc. Thus, there is a sense—an intuition at this point—that happy mailman is “noun-y.” The tests that are introduced below will provide empirical evidence that this is so.

What constituency means, practically

When I claim that a string of words is a constituent, I’m claiming that all of those words are grouped together under one label. Note that a single word, is, by definition, a constituent. A sentence is also, by definition, a constituent. What I’m ultimately trying to do when I figure out constituency is I’m trying figure out how information is packaged. How does any language put its pieces together to make a meaningful utterance?

Precisely, in any given language, I want to know which words go with which words. This allows me to write the simplest possible rules. For instance, with our DP rule, I can capture the idea that The mailman slept and The happy mailman slept both involve a subject and verb. Identifying The mailman and The happy mailman as the same “thing” simplifies my understanding—and representation—of the English language. I can reduce sentences to grammatical roles like Subject-Verb, or Subject-Verb-Object by identifying that the the term “subject” may involve something that consists of more than one word, like the happy mailman.

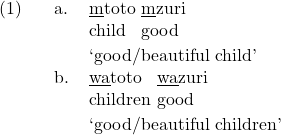

It is worth noting that in English, it is difficult if not impossible to use morphology to determine constituency, so all the tests below involve distributional evidence. But morphology is actually relevant and important in other languages in determining constituency. For instance, in Swahili, adjectives must “agree” with the nouns that they modify. This typically means that the prefix of an adjective must match the prefix on a noun.

The same point can be made in Romance languages. In Spanish, adjectives modifying masculine singular nouns appear with particular distinctive morphology -o, and adjectives modifying feminine singular nouns appear with different morphology -a. It is thus possible to identify groups of words using morphology in languages which have “richer” inflectional morphology than English. However, such morphological constituency diagnostics come with their own (considerable) complications; we will not be able to address them fully in this class.

Constituency tests

1. Substitution tests

Substitution tests are a family of tests that can be used to determine both constituency and category label. The premise behind these tests is that if you can replace the string of words in questions with something whose category you know, then the string of words must share a category with the thing you’ve replaced it with.

For instance, if I can replace, or substitute, the tired doctor with something whose category I know, then I can conclude that the tired doctor has the same category as whatever I replaced it with.

Applying the test: The tired doctor slept. → That’s right, she slept.

Step-by-step:

- Identify the string of words whose constituency you want to test.

- Identify an appropriate substitution word, whose category you know.

- Replace the string of words (and nothing else) with the chosen word.

- Check the grammaticality. If it’s grammatical and it means exactly the same thing, then you can conclude it’s a piece of evidence in favor of treating the string as a constituent.

Substitution test demonstration (length: 1m 29s)

There are two tricky things about substitution tests. First, you need to find an “appropriate” substitution word. What is and is not appropriate changes depending on what the string of words is. For instance, it wouldn’t makes sense to chose the pronoun it to replace the tired doctor, because it refers to an inanimate object (most of the time). In order to perform a substitution test, you have to make a hypothesis about what constituent you think the string of words might be. Below is a list of pro-forms that are used to test various constituents.

Various pro-forms

- Substitution of Determiner Phrases ⇒ Use a pronoun (he, she, it, they, etc). (Make sure you use the correct form of the pronoun! Don’t use he when him works better, etc.)

- Example: Carol saw the trees on the hill → Bill saw them, too.

- Substitution of Verb Phrases ⇒ Use do so, changed to reflect the appropriate tense if necessary.

- Example: Carol saw the trees on the hill → Bill did so, as well.

- Substitution of Locative Prepositional Phrases ⇒ Use there. (This won’t work for all prepositional phrases, only ones which refer to a location.)

- Carol sat on a bench → Bill sat there, too

- Substitution of clauses ⇒ Use so. (Again, this won’t work for all clauses, only certain ones.)

- Example: Carol thinks that Isabelle left → Sam thinks so, too

Thus, if you think it’s a DP, use an appropriate pronoun. If you think it’s a verb, use do so. Note that there’s nothing wrong with applying more than one test. If you’re not sure which substitution test to do, just do them all! Do any of them work? If so, you’ve learned something about the category of the constituent! But note that not all categories permit substitution. There isn’t really a substitute for adjectives in English. Likewise, in many languages, there is no substitute for verb phrases. If there is no substitute for that category, then you simply cannot apply the test. (If that comes up on an assignment, just right “N/A.”)

The second tricky thing about substitution tests is that you often need to set up a context. For instance, the sentence Bill did so, too doesn’t make sense out of context. I can’t walk into a room and say this sentence out of the blue. There needs to be an antecedent for the pro-form (do so). The same is true of any of the pro-forms above. I can’t just walk into a room and say She slept, unless you know who I’m talking about. That’s why when I demonstrate substitution, I typically put the sentences into a small discourse or exchange. “The tired doctor slept. That’s right! She slept.” The actual test is the sentence She slept, but the preceding discourse provides an antecedent for she that makes this utterance felicitous.

2. Sentence Fragments

The second constituency test we can use is called a sentence fragment test. When you apply this test, you’re asking whether the string of words in question can stand on its own. The best way to set this up is to see whether the string of words can be the response to a question.

Applying the test: Who slept? → The tired doctor.

Step-by-step:

- Identify the string of words whose constituency you want to test.

- Write down that string of words separate from the sentence.

- Try to come up with a question which could have the string as a response.

Fragment test (length: 1m 12s) credit: Emma Scott

Fragment test (length: 1m 39s)

Note that the fragment test alone doesn’t tell you what the category of the constituent is. In contrast, the substitution test, when done correctly, does tell you about the category of the constituent. If I successfully substitute a string of words with a pronoun, then I can conclude that the string of words has the same category as the pronoun. (They’re both DPs, as we’ll talk about in chapter 5). If I substitute a string of words successfully with do so, then the string of words in question is a Verb Phrase, etc. This is, essentially, marshaling the fact that the classes of words share a distribution, as discussed in the previous chapter.

3. Movement/Displacement tests

The third constituency test we can use is also a family of tests, called movement tests (or also displacement tests). In this class we’ll cover four tests. In these tests, you’re taking your original sentence, and “transforming” it by moving things around. The idea behind the movement tests is that you can only move a constituent. When first learning these tests, the easiest thing to do is to memorize a “template,” and then plug the sentence into the template. The general idea is that you want to label one part of the sentence as “A”—this is the string of words you’re wondering about—and the other part of the sentence as “B.” Then you want to put A somewhere else, leaving B alone.

a) It-clefting.

The template for it-clefting is, “It was __A__ that __B__.”

Applying the test: The tired doctor slept → It was the tired doctor that slept

Step-by-step:

- Identify the string of words that you want to test.

- Label the string of words you want to test “A,” and everything else in the sentence “B.”

- Fill in the template, It was ___A___ that ___B___. (You may need to change the tense of was.)

- Check the grammaticality of the resulting sentence.

It-clefting demonstration (length: 1m 17s)

IMPORTANT! If you find that the test works and you get a grammatical sentence, then you can conclude that A is a constituent, but you cannot conclude that B is a constituent. For example, suppose I apply the it-clefting to the following string of words.

- The doctor treated a sick patient yesterday → It was a sick patient that the doctor treated yesterday.

The test indicates that a sick patient is a constituent, but it does not indicate that the doctor treated yesterday is a constituent. You can only make conclusions about the part that you’ve moved, not about the part that is left behind. This goes for all of the movement/displacement tests.

b) Pseudo-clefting

The template for pseudo-clefting is, “__A__ is who __B__”.

Applying the test: The tired doctor slept → The tired doctor was who slept

- Identify the string of words you want to test

- Label the string of words you want to test “A,” and the rest of the sentence “B”.

- Fill in the template, A was who/what B.

- Check the grammaticality of the resulting sentence.

Pseudo-clefting demonstration (legnth: 1m 15s)

c) All-clefting

There are number of different kinds of clefts—some are language specific. The final cleft that we’ll use is an all-cleft. The template for all-clefting is, “__A___ was all (that) __B__”.

Applying the test: The tired doctor slept → The tired doctor was all who slept

- Identify the string of words you want to test

- Label the string of words you want to test “A,” and the rest of the sentence “

- Fill in the template, A was all who/that B.

- Check the grammaticality of the resulting sentence.

All-clefting demonstration (length: 2m 14s)

d) Topicalization

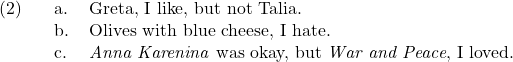

The final movement/displacement test we’ll use is topicalization. This is, in some ways, the easiest movement test, because all you’re doing is (potentially) rearranging the sentence. You’re not adding any new words in. The template for topicalization is, “__A__ , __B___”. The following are all examples of topicalization. If you’re a native English speaker, you’ll want to read these with a slight pause at the comma.

Note that it’s possible to topicalize a subject, but this might not result in a new word order, just a different intonational contour.

Applying the test: Maisha met the tired doctor → The tired doctor, Maisha met.

- Identify the string of words you want to test

- Label the string of words you want to test “A,” and the rest of the sentence “

- Fill in the template, __A__, __B__.

- Check the grammaticality of the resulting sentence.

Topicalization (length: 1m 50s)

Like substitution tests, you want to make sure with topicalization that you’ve set up the context adequately. Often the best topicalization tests involves contrastive topics. You can contrast something with something else. This is what is shown in specifically in (2c), where the topicalized phrase War and Peace is being contrasted with Anna Karenina.

Keep in mind that while I’ve shown you four movement/displacement tests, there are many, many more. Any way you can “rearrange” a sentence, while still keeping the meaning, is potentially a constituency test.

4. Coordination

The final constituency test we’ll cover is one that works in every language, but it is also the one that is easiest to give you false positives. There are a lot of ways to do the coordination test wrong.

Applying the test: The tired doctor slept → The tired doctor and Sarah slept.

- Identify the string of words you want to test

- Place a coordinator directly after that string of words.

- After the coordinator, add something that you know is a constituent, and that you think is of the same category as the phrase you’re testing. For instance, I chose “Sarah” above because I think the tired doctor might be a DP.

- Check the grammaticality of the resulting sentence.

Coordination test (length: 2m 48s)

It’s very important to keep in mind that constituency tests are not infallible. We often get false positives and false negatives. That’s why we have so many tests, so that we can confirm our results! We don’t ever really know why a test fails. Therefore, we cannot rely on negative results, only positive results. For instance, it-clefting and pseudo-clefting give different results when testing verbs (really, verb phrases):

- Nekesa grew tomatoes → *It was grow tomatoes that Nekesa did.

- Nekesa grew tomatoes → Grow tomatoes is what Nekesa did.

What do we conclude when have such conflicting evidence? Well, hopefully our other tests will help us decide whether a piece is or isn’t a constituent. In the end, there may be additional factors about certain tests and/or configurations that influence the grammaticality of the test. Something about it-clefting in English doesn’t work with Verb Phrases. A deeper investigation into the syntax and semantics of clefts may provide an answer, but it is, unfortunately, beyond what we can cover in this class.

Where we’re going

We want to know how to write the rules that describe a language. Our rules need to be informative, and they need to accurately and precisely reflect the language in question.

The constituency tests inform us about how our rules should look. If I discover that happy mailman is a constituent, then this should be reflected in our rules. More importantly, if I discover that happy mailman has the distribution of a noun, then I can conclude that this entire string of words is functionally a noun. This is a major step. By claiming that there are “noun phrases” not just “nouns” we are claiming that the category of a single word can determine the category of an entire string of words. It surely cannot be accidental that happy mailman both distributes like a noun, and also has a noun in it. Similarly, the phrase very happy distributives like an adjective and has an adjective in it.

Constituency and category (length: 1m 12s)

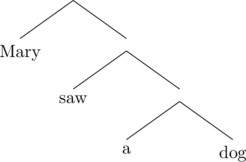

Thus, even without labels, I can correctly represent with this tree that a dog is a constituent, and that saw a dog is a constituent. And indeed, sometimes this kind of tree is the best we can do. Our constituency tests may indicate a grouping of words for which we do not know the category. That’s fine! As we noted in the last chapter, the term “category” is really just a way of saying “this is bunch of things that act alike.” The actual name of the category itself is (relatively) unimportant in the long run, as long as we can correctly characterize what distinguishes (morphologically or distributionally) a group of words or word.

Things to remember

- How to apply and interpret seven constituency tests

- What to do when you have mixed results in your constituency tests

- How constituency tests inform our syntactic representation (trees)

Advanced

It is easy to overlook how crucial—and absolutely necessary—constituency is. It is one of the most fundamental aspects of Human Language, and it is acquired by all babies at a fairly early age. The affects of constituency can be observed across a wide range of phenomena. Consider the examples (adapted from Chomsky 2021.[1]).

![]()

It is constituency that ultimately determines the form of the verb. We interpret the phrase The robbery at the pet stores as an entire unit, whose head is robbery. Thus, the verb indicates a singular subject: was. In contrast, when the head is plural, robberies, the verb indicates this, too: were.

What is crucial here is that the form of the verb is not determined by linear order. The verb doesn’t look to its immediate left to see whether that word is singular or plural. If it did, we would expect *The robbery at the pet-stores were criminal and *The robberies at the pet-store was criminal, where the choice between was and were is determined by pet-store(s). That is, we have to “see” the entire subject as a constituent in order to determine the right agreement on the verb.

Language-specific constituency tests.

We’ve explore above constituency tests in English. When we look cross-linguistically, we find that the same principles apply. Can you substitute the string of words with a word whose category you know? Can you displace the string of words to a different part of the sentence? Can you coordinate the string of words with something whose category you know?

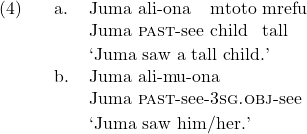

What is important to keep in mind is that each of these processes may ultimately look different depending on the language. For instance, in Swahili, the replacement test looks different because pronouns work different in that language.

In Swahili, object pronouns are attached directly to verb. Mu- doesn’t linearly replace the string mtoto mrefu—that is, it doesn’t go in the same place. But we can still use this as a constituency test, keeping in mind the independent observation that object pronouns simply have to go in a particular position. (Indeed, we could make the same point with Romance languages, in which object pronouns similarly go in front of the verb.)

Nonconfigurationality

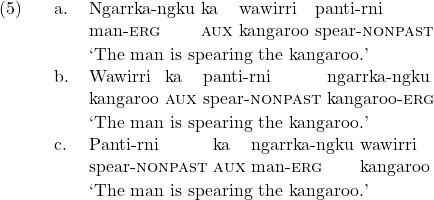

Still, while the notion of constituency has crosslinguistic validity, the crosslinguistic picture on constituency tests is fairly complicated. We make a broad (and far from absolute) distinction between languages which are configurational, like English, and those which are nonconfigurational. In a configurational, the elements in any one sentence, have a particular order that they need to be in. For instance, in English, as a rule, adjectives comes before nouns: red coat not *coat red. A nonconfigurational language is described as having “free” word order. Consider the famous case of Warlpiri, a Pama-Nyungan language spoken in Central Australia. [2]

All three orders of words are perfectly acceptable, and all three mean exactly the same thing. (The only rule is that the auxiliary element ka has to be the second thing in the sentence.) The issue that nonconfigurational languages raise is that they appear to disregard constituency. For instance, nouns and their modifiers need not be next to each other.

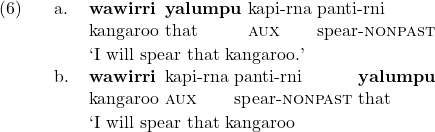

In English, we strictly cannot separate kangaroo from that, a fact which we use to determine that kangaroo and that form a constituent. So if Warlpiri allows us to do such separation, does it have constituency?

The answer is yes—but it’s complicated. As we’ll learn later in class, the order of words we pronounce is not always the order that the words started in. That is, things move, and therefore, we sometimes have discontinuous constituents because the parts of the constituent have been separated by movement. Of course, we need to show that movement has taken place, and we have a suite a diagnostic tests for this; we’ll get to them later in the class.

The takeaway here is that nonconfigurationality, in particular seemingly discontinuous constituents, ultimately are not an argument against constituency in general.

A generative syntactic theory is one which proposes a set of abstract rules can can "generate" any and every human language.

A family of constituency tests that tests constituency by replacing a string of words with another form, typically a pro-form.

An antecedent is a referring expression that forms a dependency with some lower pronoun or anaphor.

The sentence fragment constituency tests asks whether the phrase your testing can stand on its own.