14

Concepts and skills you will need for LING 527/727

- How to determine word category

- Constituency and how it is represented

- Headedness

- Functional vs. lexical categories

- Head-movement constraint

Morphology and Morphological theory

Morphology is the study of words. Morphologists look at the pieces that make up words (e.g., how many pieces of meaning are in the word sang?), what processes govern how words are made (e.g., the Head Movement Constraint), and the relationship between morphology and other aspects of grammar, like syntax and phonology. Because morphology is such a broad field, it is (arguably) the most contentious field. There is a general disagreement about what the field of morphology is even concerned with. Once central topic of disagreement concerns how much the fields of morphology and syntax are related. Or put differently: do the same “rules” that govern syntax also govern morphology?

We’ve encountered quite a bit of morphology in this book already, because I happen to subscribe to the belief that morphology and syntax are indeed quite related fields. In many ways, the connections between syntax and morphology are clear. For instance, we postulated an independent phrase TP, where tense information is introduced. But we also noted that tense is often expressed together with the verb, like walk-ed in English or ali-anguka ‘fell’ in Swahili. So if you think that TP is distinct from VP, then you need an explanation for why they are sometimes pronounced in the same word. Our explanation in the book was head-movement: V moves to T or T moves to V. This makes very specific predictions, because it puts word-formation into the syntax. An alternative theory would claim that words like walked and alianguka are not “made” in the syntax, but rather are simply inserted into the trees as is.

Other similarities are concerned with constituency and structure. Recall from Chapter 3 that we started out discussion of brackets and trees by first looking at compound words like swan-boat. Compounding is a morphological phenomenon (or a morphological process, again depending on your theoretical assumptions) which happens to precisely parallel the key aspects of syntax phrase structure: headedness and constituency.

Morphological theory is concerned with details and idiosyncracy. It is fairly easy to create a theory that captures the general pattern, but it is much more difficult to create a theory that captures all the data, including all the exceptions to the pattern. Just taking English past tense as the canonical example, we can generally say that English past tense is formed by suffixing -ed to the end of the verb, e.g., walked. But there are number of exceptions in English. The partially suppletive verbs, like teach ~ taught, bring~brought, seek~sought, fight~fought, etc are one issue. In what way are the non-past and past forms related to each other? Moreover, note that all of these verbs have similar past tense forms, ending in –ought. Is there any sense that these forms are a (synchronic) natural class? And then what do we do with the fully suppletive forms like go~went? Do we say that there are two pieces of meaning in went (go+past)? Some morphologists say yes, and some say no.

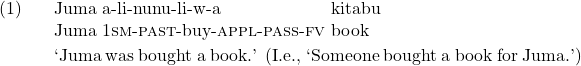

The study of morphology really gets interesting when we look at languages beyond English, and really, Indo-European in general. For instance, in Swahili, verbs may have a range of suffixes, each a distinct morpheme which supplies a particular piece of information.

Swahili packs more information into its verb than the corresponding English sentence, indicating with –li that the buying was “for” someone (an applicative suffix). The passive -w indicates that the verb is a passive form; Juma is the recipient of the action.

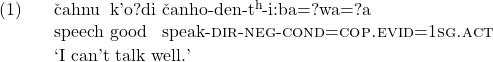

Native American languages are also offer important lessons in morphology, with many being extremely complex. Consider Southern Pomo, which can pack an extraordinary amount of information into the verb.[1]

- This example is from Neil Walker (2013) A Grammar of Southern Pomo: An Indigenous Language of California. PhD thesis. University of California, Santa Barbara. p. 401 ↵

ADD DEFINITION