10

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to,

- diagnose unaccusative and unergative verbs

- draw trees representing the unaccusative/unergative distinction

- understand the motivation for a low position of transitive/unergative subjects

- understand the motivation for Voice

We have seen empirical evidence that the subject of the sentence (in the languages we’ve looked at) is in spec-TP. More specifically, we’ve seen evidence that spec-TP is filled at S-structure.

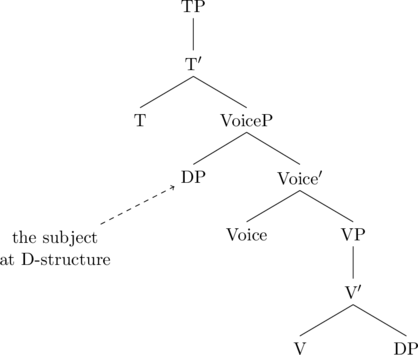

In this chapter, we’re going to discover that the subject doesn’t start there; it moves there. Again more specifically, at D-structure, spec-TP is empty. Subjects start lower in the tree and move to spec-TP.

This is phrasal movement, that is, the movement of phrases (rather than heads, discussed in chapter 7). Phrasal movement is divided into two distinct domains: A-movement and A’-movement. This chapter will deal exclusively with A-movement. A’-movement is addressed in chapter 10.

We’ll approach phrasal movement in steps. First we’ll show that some subjects can move to spec-TP. Then we’ll show that all subjects move to spec-TP. We’ll then deal with the question of where the subject starts from.

A quick refresher of what what was covered in chapter 8.

- Verbs c-select their arguments. That is, they dictate how many, and what kind of, phrases they are required to appear with.

- Verbs s-select their arguments. That is, they dictate the semantic properties, including thematic roles, of their arguments.

- Every argument has one (and only one) theta-role .

- Every theta-role always appears in the same “syntactic configuration” (=UTAH).

Unaccusatives and unergatives

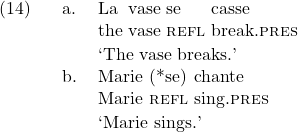

Consider the verbs in (1a) and (1b).

![]()

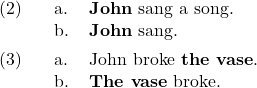

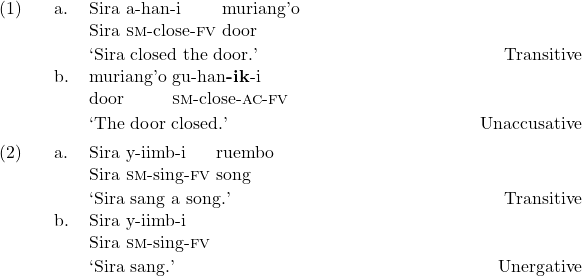

The question we will consider is whether (1a) and (1b) have the same tree. That is, if they’re both intransitive verbs, do they both simply have a subject in the specifier of TP? Possibly. Call this Hypothesis #1.

All subjects of intransitive verbs start in spec-TP.

This hypothesis is what we have been assuming: there is a dedicated subject position, and all subjects sit there.

However, there’s an alternative hypothesis which follows from our observation that thematic roles are associated with particular positions in the syntax (i.e., UTAH). Notice that the parallelism between the intransitive verbs breaks down when we look at the transitive verbs. With sing, John is the subject of the transitive verb and the subject of the intransitive verb. But with break, the vase is the object of the transitive verb and subject of the intransitive verb.

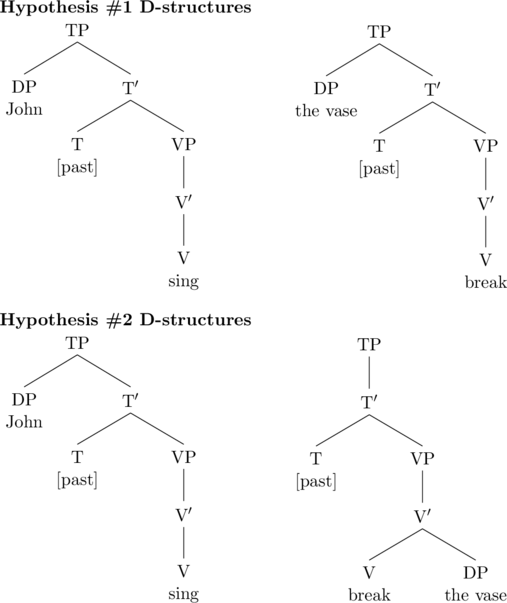

Thus, the alternative hypothesis is that, because the vase is a Patient in both the transitive and intransitive verb frames (it undergoes a change), it starts life as the object of break, and then moves to the subject position. This follows from UTAH, because UTAH holds that the Patient thematic role is always syntactically represented as the complement to V. Call this Hypothesis #2.

Some subjects of intransitive verbs start as complements to V.

The idea behind hypothesis #2 is that when there is no Agent, the object of break becomes the subject by moving from comp-VP to spec-TP.

The following diagnostics allow us to determine which of the two hypothesis is correct. In fact, the data suggest that hypothesis #2 is right. We distinguish two kinds of intransitive verbs.

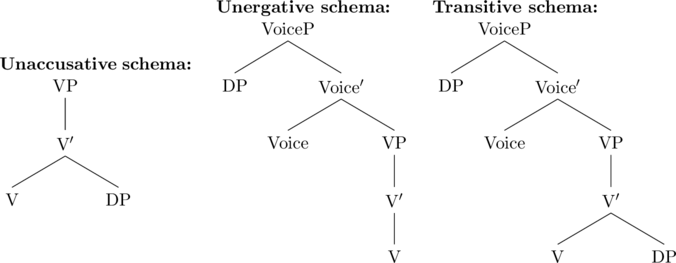

Unergatives are intransitive verbs that lack an object, i.e., only have an external argument.

Unaccusatives are intransitives that lack a subject, i.e., only have an internal argument.

Note that when we say “lack a subject,” we mean that they lack a subject at one level of representation: D-structure.

Unergatives and unaccusatives differ empirically on a number of levels. All the following diagnostics highlight the crucial difference between unergatives and unaccusatives: the former lack an internal argument, while the latter lack an external argument. That is, you can use these as tests to determine whether a verb is unaccusative or unergative.

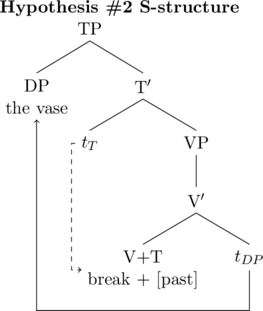

Resultatives test.

A resultative phrase is a phrase that describes a “result state.” For instance, in Keisha broke the vase into pieces, the phrase into pieces is a resultative, because it describes the result state of the vase after Keisha broke it.

Unaccusatives permit modification of the object with a “resultative” phrase, i.e., something that describes the result state of the object.

The idea behind this test is that resultative phrases are in some kind of relationship with the object of the sentence. When I say, Keisha broke the vase into pieces, I’m describing the state that the vase was in after Keisha broke it. More abstractly, I’m saying something like “Keisha CAUSED the vase BE in pieces,” where “CAUSE” and “BE” are abstract verbal notions. The intransitive sentence The vase broke into pieces is simply missing the CAUSE abstract verb, but the predication “the vase BE in pieces” is still present.

Unergatives don’t allow resultatives because the intransitive subject isn’t in the same relationship with the resultative phrase: the predication “John BE in pieces” or “Mary BE solid” does not work in (5) because John and Mary were never objects of the verb (and therefore cannot be modified by the resultative).

Resultatives test (length 59s) credit: Malena Schoeni

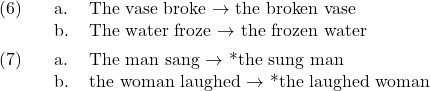

Participial modification.

You can use unaccusatives as participial modifiers.

The idea behind the participial modification test is that the participial form of the verb still subcategorizes for an object position, but excludes a subject position.

Participial modification (length: 45s) credit: Corey McCulloch

X’s way/X-self.

You can add either X’s way or X-self to unergatives, but not unaccusatives.

The idea behind this test is that with unergative verbs, there is no object, and so something else can be placed in that position. That is, you can “give” an unergative verb an object because comp-VP is, in a sense, “free.” You can’t give unaccusative verbs an object because comp-V is already occupied; there’s nowhere to put an extra object.

X’s way (length: 45s) credit: Corey McCulloch

Cognate objects.

Unergatives allow an object that expresses the same thing as the verb — a cognate object, which is a noun that describes the same action as the verb.

This test has the same purpose as the X’s way/X-self test: it’s diagnosing whether the object position (comp-VP) is empty. If it is, you can put a cognate object in the structure.

Unaccusative syntax (length: 1m 31s)

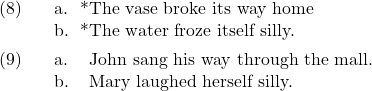

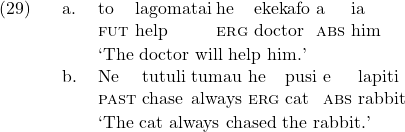

Crosslinguistic evidence for the ergative/unaccusative distinction

The so-called Unaccusative Hypothesis has quite a bit of evidence in its favor, and a lot of that evidence come from crosslinguistic patterns.

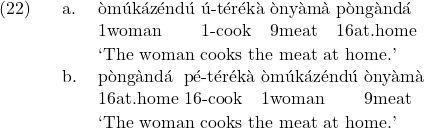

Auxiliary selection.

In many languages, particularly Indo-European languages like Romance and Germanic, the auxiliary used to express past tense/perfect aspect is (at least superficially) sensitive to the distinction between unergatives and unaccusatives. In many languages, the auxiliary verb be is used for unaccusatives, and have is used for unergatives.

Morphological distinctions.

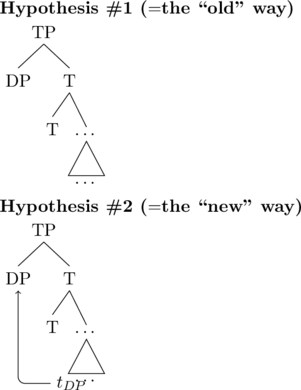

In many languages, there are morphological indicators that distinguish unaccusatives and unergatives. For instance, in Romance languages, many unaccusatives obligatorily occur with the so-called reflexive clitic se/si. Unergative verbs never appear with reflexive clitic.

In Logoori, a Bantu language of Kenya, many unaccusative verbs appear with the suffix -ik. Unergative verbs may never appear with this suffix.

To be clear, we have to be somewhat cautious about our diagnostics and evidence. While the data listed above can pick out unaccusatives, it is not guaranteed that an unaccusative verb must display all the properties listed above. For instance, the English verb arrive does not permit cognate objects, but also does not permit participial modification.

![]()

Despite this divergent evidence, we generally believe that arrive is unaccusative. This is in part based on cross-linguistic evidence, and also in part based on factors we do not have time to consider here.

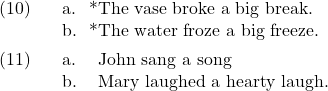

On passivization

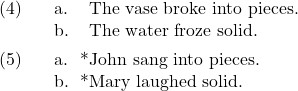

We’ve shown above that sometimes, the subject moves to spec-TP. Indeed, there is pretty clear evidence that not all subjects start in spec-TP just from passivization. Passivization is a syntactic process that turns a transitive verb into an intransitive verb.

![]()

The subject in (15b) starts as the object of break, and then gets “promoted” to the subject position. This is just like the unaccusative syntax we observed earlier: the D-structure object becomes the S-structure subject. However, passives and unaccusatives differ in a few crucial ways. Most notably, passives allow the external argument to be expressed as an oblique argument (in a prepositional phrase). Unaccusatives do not permit this.

![]()

This suggests that even though both passives and unaccusatives involve movement of an object to a subject, they mean slightly distinct things. The passive alternation in English is complex, and so we’re going to put it aside here.

Generalized movement to spec-TP

We now know that some subjects don’t start in the specifier of TP, they move there. Specifically, unaccusatives (and passives) demonstrate that not all subjects start in D-structure in the specifier of TP.

Now let’s ask whether anything starts in spec-TP.That is, we used to have a uniform theory: subjects starts in spec-TP. Now we have a “split” theory: some subjects start in spec-TP, some move there. Now we’re going to explore whether a uniform theory is still possible: maybe all subjects move to spec-TP.

Though we’ll go over empirical evidence for this momentarily, note that purely on theoretical grounds, having subjects of transitive and unergative verbs start in spec-TP is fishy. In all other cases, selection is local, meaning that “a head dictates the syntax around it” (as discussed in chapter 8). The problem appears to be that subjects (of unergative and transitive verbs) aren’t next to what is selecting them. That is, if sing is unergative and it selects for its subject, why is the subject so far away from the verb in examples like (17)?

![]()

In the following sections, we’ll again be weighing two hypotheses. The first hypothesis is the null hypothesis: subjects of transitive and unergative verbs start in spec-TP, just like we’ve been doing. The second hypothesis is that subjects start somewhere closer to the verb. (We’ll be more precise about where shortly.) That is, nothing starts in spec-TP. Everything that we pronounce in spec-TP has moved there. The two hypotheses are sketched below.

These hypotheses make different predictions.

Hypothesis #1 predicts that a transitive/unergative subject can never be pronounced in the verb phrase, and that there is no evidence for movement to spec-TP.

Hypothesis #2 predicts that a subject can be pronounced in the verb phrase (if it hasn’t moved), and that there is evidence for movement to spec-TP.

So we’re looking for two kinds of data.

- Is there evidence for a low position of the subject?

- Is there evidence for movement to spec-TP?

There’s lots of evidence for 1., and a bit of evidence for 2. Let’s start with arguments that the subject can be pronounced lower than spec-TP.

Evidence for a subject low position

Small clauses.

Some clauses are “smaller” than others. The bracketed constituents are missing a tense phrase (TP).

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{17} \ex. \a. I saw [ Mary hug a pedestrian ] \b. I heard [ John sing ] \c. I made [ Carrie build a house ]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-75ca01d0e775a0978d05eeb6df37580d_l3.png)

The subjects of hug, sing and build are not in spec-TP because there is no TP above hug, sing and build. (You can tell because hug, sing, and build do not—and cannot—appear with tense morphology: *I saw Mary will hug a pedestrian.) How could Mary, John and Carrie even get into the tree if all subjects start in spec-TP? These data suggest that Hypothesis #2 is correct, because Hypothesis #1 predicts subjects are only found in spec-TP; if there’s no spec-TP, there can be no subject.

Existential constructions.

Consider the following alternation. There in (19b) is called an expletive subject. Expletive subjects are semantically vacuous.

![]()

Again, these example suggest that, at least sometimes, the subject of the sentence can be pronounced not in spec-TP. In the case of expletive there, something else sits in spec-TP, namely there, and so the subject three women must be somewhere else—somewhere lower.

Should we also consider the possibility that there (and expletive it) start lower in the clause? Maybe, but the rule of thumb is that it and there are not semantically selected by the verb. Expletive subjects are inserted to satisfy the requirement that every clause needs a subject, and so expletive subjects do not start in the verb phrase, they start in spec-TP.

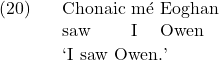

VSO languages.

Many languages have a word order that suggests that the subject stays “low” in the clause. Consider Irish, which has canonical Verb-Subject-Object ordering for declaratives sentences.

These data make sense if V moves across the subject to T, and the subject stays low. Thus, they are most consistent with hypothesis #2. They are only consistent with hypothesis #1 with additional stipulations.

Locative inversion.

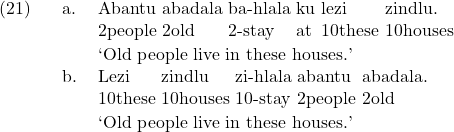

Here’s some data from Zulu (from Buell 2007). In Zulu, locative phrases can be in spec-TP, triggering agreement on the verb; we see agreement between houses (noun class 10) and the subject prefix on stay in (21b).

Herero (Bantu) shows the same thing. (Data from Buell 2007 as well.)

Notice in this pair that the English translation is the same for both sentences!

Locative inversion data are also consistent with Hypothesis #2, but are not consistent with Hypothesis #1. Under Hypothesis #2, what is happening with locative inversion is that something other than the “logical” subject gets to move to spec-TP, namely, the locative phrase. With Hypothesis #1, the word order doesn’t seem possible: if the subject is always in spec-TP, how could we possible derive the word order where it appears after the verb?

Evidence for movement to spec-TP.

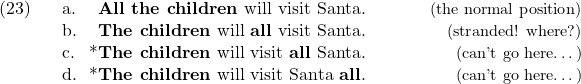

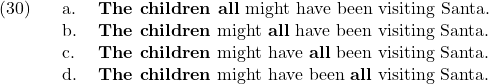

Quantifer float.

Some quantifiers can appear separated from the noun they combine with. This is called quantifier float.

The first two examples show us where all can go:

- It can appear in front of the DP.

- It can appear in front of the verb.

These data make sense if quantifiers like all can “float” in positions that the subject has occupied. Phrased differently, the data make sense if all can be “left behind” when the subject moves to spec-TP. All appears wherever the DP used to be. The ungrammatical sentences confirm this: we can’t put all after the verb because the subject was never after the verb.

Voice aka “Little V”

In sum, the empirical evidence suggests that even subjects of transitive and unergative verbs start lower in the structure. The question we’ll address here is where precisely the subject begins life.

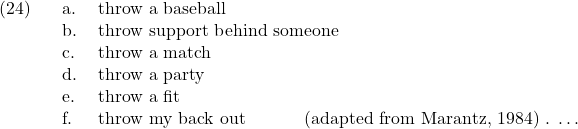

We said in chapter 8 that a verb like throw selects its subject. If I asked you what thematic role throw assigns to its subject, you’d probably say Agent. But consider the verb phrases in (24). All of these involve the verb throw, but the object varies.

Interestingly, we see that the thematic role of the subject depends not on the verb alone, but rather the combination of the verb and object. Throwing a baseball is not the same act as throwing a fit, or throwing my back out. In each case, the subject has a distinct thematic role, depending on both the verb and the object.

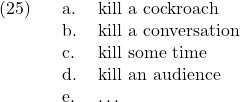

The same thing can be demonstrated with the verb kill. Again, if I asked what thematic role kill assigns to the subject, you would probably say Agent. But now consider what happens when we vary the object.

Again, it looks like it isn’t just the verb, but the combination of verb and object that determines the semantic role of the subject. For instance, My feet are killing me, certainly cannot be attributing an Agent thematic role to my feet. Likewise, Stephen kills time by playing Switch does not attribute to Stephen the same thematic as in, Stephen killed a cockroach.

The generalization is that selection of the subject depends on the entire VP, not just V. That is, the combination of verb and object together—the VP—determines the thematic properties of the subject. For our theory then, we then need a way to relate the VP to the subject. We will adopt the functional projection Voice to perform this role.

Like other functional heads, Voice’s job is to provide a relation between two phrases. Voice maps the subject to the VP—or more specifically, it relates the subject to the event described by the VP. It allows the VP to dictate the thematic properties of the subject.

More generally, Voice controls the transitivity of the verb. We will assume for simplicity in this class that transitive and unergative verbs require Voice, but unaccusatives do not. This is, however, a significant simplification of the issues.

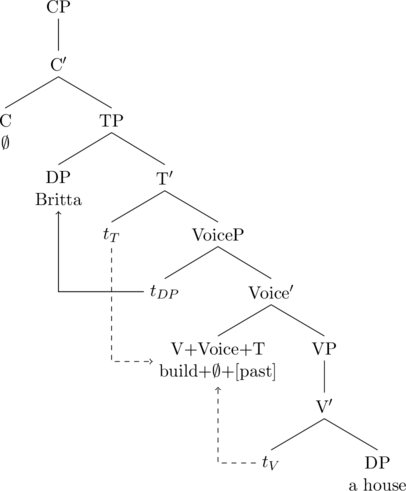

Adding Voice requires a small modification to our T-lowering rule. We’ll assume that instead of T lowering to V, it lowers to Voice, and that V raises to Voice. They “meet in the middle.” (Nothing changes for unaccusatives; T still lowers to V.)

This is basically a stipulation. For exposition’s sake, we will not bother to justify the movement of V to Voice. It is probably necessary for theory-internal reasons (in English), though if V didn’t move to Voice, nothing in our theory would be significantly affected.

Voice in trees (length: 2m 27s)

Key Takeaways

Voice always introduces the external argument. That is, when it’s in the tree, it serves the function of bringing in the argument that does not start inside of the VP (as the complement to V).

You need Voice above the VP if,

- the verb is transitive, that is, has both a subject and an object, or

- the verb is unergative.

The only times you don’t have Voice above the VP is if,

- the verb is unaccusative, that is, has a single argument which starts as the object of the verb, or

- the verb is an auxiliary verb.

In other words, unaccusatives and auxiliary verbs do not select for an external argument, and so do not need Voice.

The Unergative/unaccusative distinction beyond verbs

We have focused above on detecting unaccusative and unergative verbal predicates. It has been argued, however, that the distinction extends to other categories, notably, adjectives. For instance Hans Bennis argues based on data from Dutch that the adjective duidelijk ‘clear’ is unaccusative, while the adjective trouw ‘loyal’ is unergative.[1]

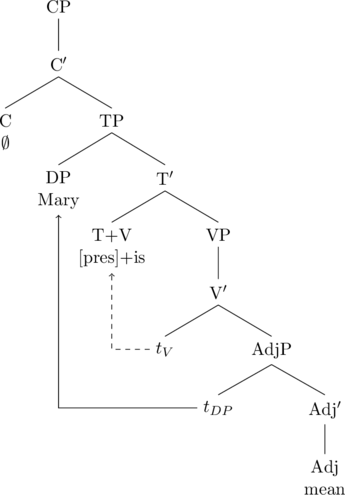

To prove this distinction requires a separate set of diagnostics from what we’ve introduced above, so we will put aside the alternation for adjectives here. However, we still need a place to generate the subject in a sentence like Mary is mean. Since mean selects for a subject, and assigns it a thematic role, Mary must be selected by mean. We will assume that it is introduced in the specifier of AP, and subsequently moves to spec-TP. This conclusion is consistent with everything we’ve said above: spec-TP is always empty at D-structure.

Morphological evidence for Voice

The reasoning for Voice so far has been largely theory internal. When we look cross-linguistically, however, we find a great deal of evidence for a Voice head. For instance, consider the morphology of the following alternations in Kunuz Nubian (data from Abdel-Hafiz 1988).

| Intransitive | Transitive |

| dab ‘disappear’ | dabir ‘disappear’ |

| bokki ‘hide’ | bokkir ‘hide’ |

| wacci ‘crack’ | waccir ‘crack’ |

| bassi ‘leak’ | bassir ‘leak’ |

What is the pattern? To make a transitive verb from an intransitive verb in Kunuz Nubian, you add the suffix –ir (with possibly vowel deletion with verb-final roots). Why is this meaningful? It shows that the difference between transitive and intransitive is not just the addition of a subject, but you actually add something to the verb.

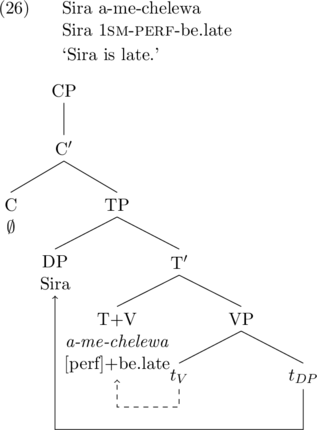

Swahili also has a suffix –ish or –esh that does something similar.[2]

| Intransitive | Transitive |

| -rudi ‘return’ | -rudisha ‘return sth, bring sth. back’ |

| -chelewa ‘be late’ | -chelewesha ‘make late, delay’ |

| -fa ‘die’ | -fisha ‘destroy, cause to die’ |

| -enda ‘go, move’ | -endesha ‘make go, drive’ |

| -weza ‘be able’ | -wezesha ‘enable’ |

If there were no Voice head, then we couldn’t explain why there is a systematic distinction between transitive/intransitive pairs. If we simply claim that the causative affix in Kunuz Nubian and Swahili are just how you pronounce Voice on transitive verbs, then the issue goes away.

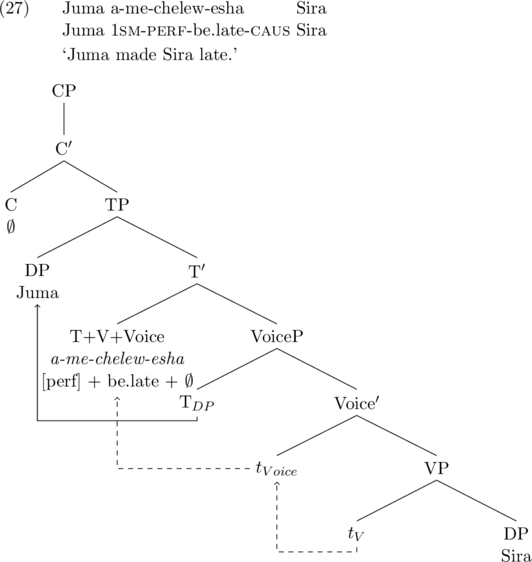

The following examples illustrate the phrasal movements and Voice. (Recall that in Swahili, V moves to T, so the head-movement goes up the tree, stopping at Voice on the way.)

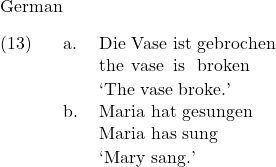

Double-Object Constructions

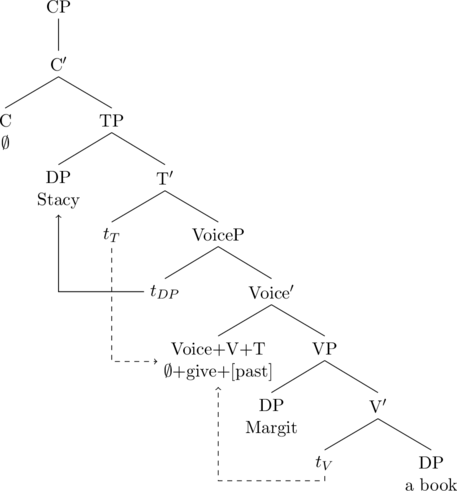

We’ve been dealing exclusively with intransitive and transitive verbs, but we can also sketch a solution to transitive verbs, like give, which selects for two objects in (28), Margit and a book.

![]()

This is called a double-object construction because the verb give appears to have two objects. We can say that the indirect object (Margit) is introduced as a specifier to VP, since this position in completely open!

Where we’re going

In this chapter we introduced the idea that all subjects start lower than TP, and move there (at least in English and the languages we’ve looked at). This is phrasal movement, meaning the movement of phrases. Recall that the impetus for head-movement (the movement of heads) is, basically, word-formation. The suffix -ed in English just can’t stand on its own; it has to be part of a word, and so either T moves to V, or V moves to T.

So what is the impetus for phrasal movement? The answer to this question is much more complex. For the movements we’ve looked at in this chapter, we might say that the impetus for movement to spec-TP is simply that “every clause needs a subject.” This idea can be syntactically encoded in the following constraint.

Spec-TP must be filled at S-structure.

It’s a stipulation, but it is “surface true,” meaning that it appears to be a good generalization about English, and many other languages as well. There is something “special” about spec-TP in that it must be filled in the surface structure. Indeed, the idea that spec-TP “wants” to have something in it will lead us to consider other cases of movement to the subject position in the next chapter.

As we’ll discover in chapter 10, there are some movements that cannot be explained in the same way. It is an ongoing research question as to why things move.

Key Takeaways

- identifying and representing unaccusative and unergative predicates

- diagnostics for low position of (unergative/transitive) subjects

- evidence for Voice

- drawing trees representing movement to spec-TP

Exercises

VSO tree drawing

Here’s some data from Niuean (from Woolford 1991). What do you observe about this data that bears on the question of whether the subject is low or high? (Notice the placement of the adverb!)

Straight to spec-TP?

Consider again the data illustrating quantifier float in English, this time with the addition of the modal might. Think about the different positions that all can “float” (i.e. be left behind), and what this tells us about movement. How does the subject get to spec-TP?

Surface structure. This is the structure that built after movement and selection have been satisfied.

D-structure (or Deep-structure) is the level of representation before movement. It the level at which selection is satisfied must be satisfied.

The Uniformity of Theta Assignment Hypothesis. This hypothesis holds that each thematic role has a dedicated position in the syntax.

An external argument is any argument of the verb that is introduced outside of the VP---it is "external" to VP.

An internal argument is any argument of that is introduced inside of the VP---it is "internal" to VP.

A syntactic process in which an object is promoted the subject position, and a subject is demoted to an adjunct.

An oblique argument is "non-core" argument. Non-core argument are typically adjuncts, and very often appear in prepositional phrases (in English) or in semantic cases (like "instrumental") in other languages.

Expletive arguments are semantically vacuous, appearing only to satisfy syntactic constraints like c-selection and/or the Subject Condition.

A process by which quantifiers appear in places that have been moved away from.