12

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to,

- recognize and represent A’-movement

- determine instances of A’-movement

- understand the difference between A- and A’-movement

In the last two chapters, we’ve been exploring the movement of phrases. This involved substantial discussion of argument structure, and in particular, the position of subjects.

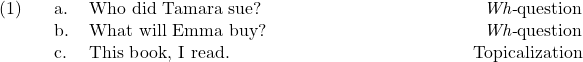

In this chapter, we’ll explore the second side of phrasal movement. The cases we’ll look at below are in some ways more “obvious” examples of movement. We will clearly see that some constituent is being pronounced in a place where we do not expect it to be pronounced. Some examples of the movement that we’ll be looking at here are given below.

As we can see in the above examples, some pre-sentential element corresponds to some “gap” later in the sentence. In all three cases, the first noun phrase corresponds to the object, which we expect to be pronounced after the verb. It is more obvious in (1) that something has moved, because not only is there something in a position that it shouldn’t be, but there’s also something missing after the verb where the object should be. We generally refer to this empty space as a “gap.”[1]

This kind of movement is clearly phrasal movement, as it can involve moving more than just one word (Which book will Emma buy?). Crucially however, this type of movement does not affect argument structure; who in (1a) is the object the verb, wherever we move it. Or stated differently, this type of movement can doesn’t change the grammatical role of the element that has moved. The movements in the previous chapter are different: all the phrasal movements we’ve previously considered “created” subjects. For instance, moving the object of unaccusative V turned this object into a subject.

One of the main findings of the last few decades is that phrasal movement comes in two varieties. We looked in the last two chapters at A-movement. The examples above are called A’-movement (pronounced “A-bar movement”).

A’-movement : Movement to a non-argument position.

The two kinds of movement have distinct, identifiable characteristics. Generally, A-movement “creates” subjects (and objects) by moving them to the “subject (and object) positions.” For example, the A-movement cases we’ve seen have all involved movement to spec-TP, which is the “subject position” in English (and many many languages). In contrast, A’-movement does not “create” subjects and objects, it merely moves them around. In the example in (1c) above, the book is an object of read, but it’s been moved to the front of the sentence. The movement to the front of the sentence didn’t affect the “objecthood” of the book; it was for other reasons.

So this is the core distinction between A- and A’-movement. That said, both kinds of movement also have a “signature,” i.e., a core set of properties that we can use to diagnose whether something has moved via A- or A’-movement.

The landing site of A’-movement

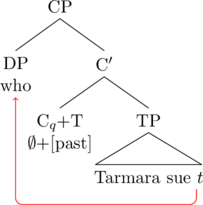

As the above examples demonstrate, things can be moved to a pre-sentential position (meaning a position in front of the sentence). What is that position?The only phrase above TP is CP, therefore, this movement must target (i.e., land in) the specifier of CP. So wh-movement lands in spec-CP.

In general, the strategy for wh-questions in English is: “Move the wh-word to the front of the sentence, and move T to C.” Notice that since this is a question C (Cq), we expect to see T-to-C movement, just like with polar questions (i.e., Did John see Mary?).

One tricky thing about wh-question formation in English involves subjects (again!). Consider the subject wh-questions below.

![]()

Although it looks like there’s no movement, such examples are in fact perfectly compatible with the description above. Some of the movements here are “string vacuous,” meaning that they do not affect the linear order of the constituents.

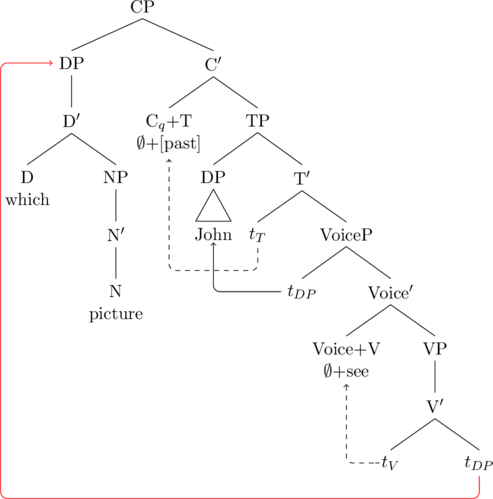

In the tree below, A-movement is represented in black, while A’-movement is represented in red. The idea here is that since we expect T-to-C movement to apply in question formation, the subject wh-word must move to spec-CP to yield the observed linear order.

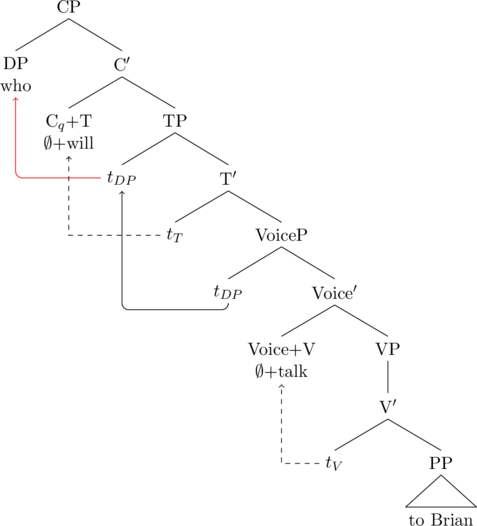

As usual, things get more complicated when do-support comes into the picture. The problem can be illustrated in the following sentence.

![]()

We expect to see something like *Who did call? This is because T moves to C in questions, and therefore shouldn’t be able to appear on the verb. There are a couple of solutions to the puzzle — but they all involve simply outright stipulating the solution.

For our purposes, we’ll assume that T-to-C movement applies, and then a “magical” (=morphological) process allows the complex to come together with V after syntax.

Many sentences will now have at least two phrasal movements. There will almost always be something moving to spec-TP (unless there is an expletive subject), and then there might be something moving to spec-CP. There is a general and robustly attested “ordering” of movements. A-movement always precedes A’-movement. Practically, this means that you should move to spec-TP before you move anything to spec-CP.

Subject wh-question (length: 3m 5s)

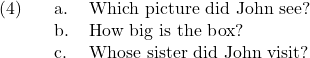

Pied-Piping

Often, more than just the wh-element moves. This is called pied-piping.

In most cases, there’s a very intuitive explanation for why pied-piping happens: you simply can’t separate some things. For instance, can we ever separate a determiner and it’s corresponding NP? Likewise, how could we get whose to move, since it’s not even a constituent?

Evidence for movement

As always, we want to support our analysis with data. It’s not enough to say, “Look, the wh-word is at the front of the sentence, it must have moved there.” We want to show empirically that movement has occurred.

Binding.

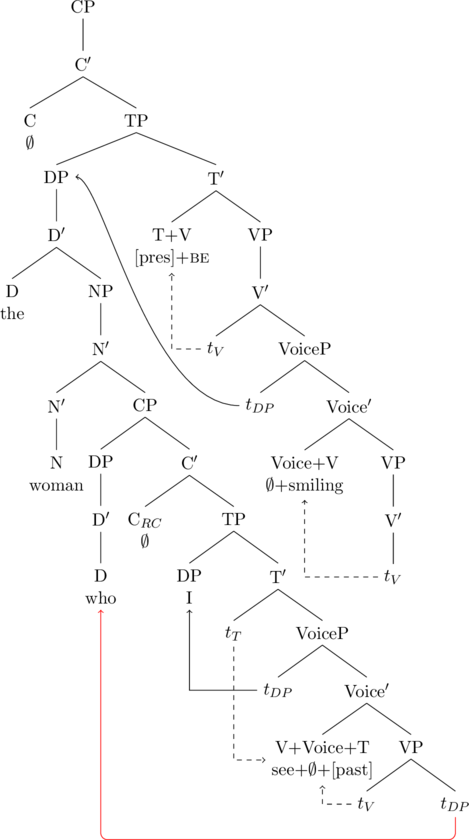

Binding Theory and phrasal movement interact. The following sentences illustrate that movement must have taken place.

![]()

In (5a), we have an anaphor. Recall that anaphors are subject to Condition A of Binding Theory. In order for that to happen, at some point himself must have been bound by John. That must have happened before movement.

On the other hand, in (5b), we have an R-expression, which is subject to Condition C of Binding Theory. Here, the movement appears to “rescue” the sentence, since if picture of John were pronounced as the object of the verb, it would be ungrammatical: *Hei saw the picture of Johni.

Languages with overt C.

Some languages actually pronounce the complementizer, like Irish:[2]

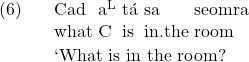

After the wh-word cad, the complementizer aL appears, showing that the wh-word comes before (=above) C.

Wanna contraction.

There are strong intuitions about when it’s possible to contract want+to into wanna in English.

This pattern suggests that you can contract wanna in (7b) because the wh-word who started at the end of the sentence. In (7c) on the other hand, the gap is the subject position of the nonfinite clause: Who does John want __ to talk to Mary? We can explain this ungrammaticality if we simply say that you can’t contract across traces.

Other instances of a’-movement

Embedded questions

Questions can be “embedded” under certain verbs:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{7} \ex. \a. Bill knows [ who saw Mary ] \b. Susan wondered [ how Mary fixed the car ] \c. Sarah decided [ which book she should buy ]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-df472a309dc9470ffae2faa3cd21bd4a_l3.png)

Embedded questions are formed exactly like regular questions, except that there’s no T-to-C movement in the lower clause.

Relative clauses.

Another place where we see A’-movement, in particular wh-movement, is relative clauses.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{8} \ex. \a. the woman [ who I saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] is smiling \b. the man [ who {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} laughs ] arrived. \c. I licked the fork [ which I eat with {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-3362e2576b28624fe01e40146ae7af6a_l3.png)

Relative clauses (in English) involve the following properties:

- There’s a gap (a trace) inside of a CP

- The CP is adjoined rightward to NP

- There is A’-movement

- There is no T-to-C movement inside of the relative clause.

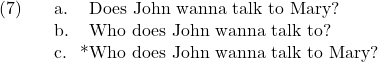

The following is the representation of The woman who I saw was happy.

This tree looks much more complicated than it actually is. The trick here is realizing that there are two clauses. If I take away the constituent who I saw, I would just have the sentence, The woman is smiling, and we know how to draw that tree: the subject the woman is selected by smile and so starts in spec-VoiceP and then moves to spec-TP. The relative clause is entirely independent of this process. You build the relative clause and attach it to the NP as a modifier.

In English, there is a relatively large amount of variation in how you pronounce a relative clause. The following sentences all have identical structures.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{9} \ex. \a. The woman [ who I saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] is smiling. \b. The woman [ that I saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] is smling. \c. The woman [ I saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] is smiling.](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-a051a65d936bd7bd7aaf32d475027a19_l3.png)

In all three cases, there has been wh-movement of who to spec-CP of the relative clause. In the first case, we pronounce who. In the second case, we don’t pronounce who, but we pronounce the complementizer that. And in the third case, we pronounce neither. Since this doesn’t appear to affect the meaning at all, we assume that the structure is identical in all cases.

In English, there appears to be a rule of pronunciation that says that you cannot pronounce both a wh-word and a complementizer at the same time. This has been called the Doubly-Filled Comp Filter. (Note that there is in fact dialectal variation with respect the Doubly Filled Comp filter. In some dialects, it’s actually acceptable to pronounce both who and that.)

Relative clauses should not be confused with complex-NPs. The example in (11a) is a relative clause. The example in (11b) is a complex-NP.

![]()

Relative clauses have gaps, which we analyze as movement, while complex-NPs do not.

Cross-linguistic variation in A’-movement

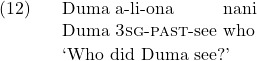

Not all languages display wh-movement to spec-CP. For instance, Swahili has wh-in situ.

The typological variation in (non-)movement of wh-expressions is fascinating, and it has inspired a huge amount of literature. It is a major focus of Syntax II, LING 526.

Differences between A- and A’-movement

Generally, syntax can be viewed as the investigation of silence. Many of the core syntactic problems arise in places where we expect to see something pronounced, but instead we see nothing. It is the job of the syntactician to discover why there’s silence.

- Option #1 : There’s a silent element. For instance, pro and PRO are silent elements. They’re DPs that aren’t pronounced.

- Option #2 : There’s movement.

- Option #2a : It’s head-movement. We recognize this movement because it forms new words.

- Option #2b : It’s phrasal-movement.

- Option #2b.i : It’s A-movement.

- Option #2b.ii : It’s A’-movement.

- Option #2: There’s ellipsis. In this case the silence arises through “deletion.” We won’t address ellipsis phenomena in this class. See LING 526.

For instance, in clefts there’s clearly a gap, and if we want to analyze this structure, we have to figure out how this gap was formed. Is there a silent element? Is there movement? If there’s movement, what kind of movement?

![]()

Clearly, this cannot be a case of head-movement; the gap does not contribute to making a new word. So this is either a case of a silent element, or phrasal movement.

In this chapter, we’ll discover that different kinds of phrasal movements have a “signature.” That is, it is possible to identify through diagnostic tests whether something a) has moved at all, and b) whether it has undergone A or A’-movement.

A’-movement diagnostics

Perhaps the defining characteristic of A’-movement is that it is unbounded: the moved element can be any number of clauses away from the gap.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{13} \ex. \a. Who did John see {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} \b. Who does Mary think [$_{CP}$ that John saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] \c. Who did Bill say [$_{CP}$ that Mary thinks [$_{CP}$ that John saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] ]? \d. Who did Carol hear [$_{CP}$ that Bill said [$_{CP}$ that Mary thinks [$_{C}$ that John saw {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] ] ]?](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-f26a5e89150ac759de76f36274a89ca6_l3.png)

The term “unbounded” here has nothing to do with Binding Theory. As it applies to movement, “boundedness” refers to the ability to move across clausal domains.

Descriptively, A’-movement can cross an infinite amount (up to cognitive limitations) of CPs. This makes it different from A-movement, which cannot cross any CPs. That is, I cannot raise to subject across a CP:

![]()

However, A’-movement is not an “anything goes” movement. That is, there are some movements that are impossible. For instance, it’s not possible to move to a position that doesn’t c-command the trace. That is, you cannot move into spec-CP of a CP in the subject position.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{15} \ex. \a. {} [$_{CP}$ That John came home early ] frightened Mary. \b. * [$_{CP}$ Which student (that) John came home early ] frightened $t_{DP}$](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-553f4f27b1a7789ff350e8c4b6f42053_l3.png)

One way to understand this is that traces are kind of like anaphors in that they are subject to a version of Condition A: they have to be c-commanded by a co-indexed element.

More interestingly, even though A’-movement can cross CPs, it cannot cross all CPs. There are some clauses that you simply cannot move out of. These are called islands. It’s a metaphor: the constituent is an island if nothing can get “off of” (i.e., move out of) the island.

In addition to unboundedness, islands are part of the “signature” of A’-movement. That is, as a rule of thumb, A’-movement “respects” islands, meaning that all A’-movement are sensitive to islandhood diagnostics. There are many islands; we’ll cover four in this class.

Complex-NP Constraint.

Recall Complex-NPs, which are CP complements to N. (They don’t have a gap). You cannot move out of CP that is complement to NP.

![]()

Adjunct island.

You cannot do A’-movement out of a clause that is adjoined. Adjoined clauses are typically headed by complementizers like because, if, when, after, before.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{17} \ex. \a. John went home [$_{CP}$ after he broke the vase ] \b. *What did John go home [$_{CP}$ after he broke {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] \ex. \a. Sarah ducked [$_{CP}$ because Ben kicked the ball ] \b. *Who did Sarah duck [$_{CP}$ because {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} kicked the ball ]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-86801bb7382b101c9890f24533dd3a78_l3.png)

Wh-island constraint.

You cannot do A’-movement out of something that already has a wh-movement. For instance, you cannot do wh-movement out an embedded question.

![]()

Compare this with (21), which doesn’t have an embedded question.

![]()

Subject islands.

You cannot move out of a constituent that is in the subject position.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \setcounter{ExNo}{21} \ex. \a. John read [$_{DP}$ a book by Tolstoy ] \b. Who did you [$_{DP}$ read book by {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ]? \ex. \a. {} [$_{DP}$ A book by Tolstoy ] is on the table. \b. *Who is [$_{DP}$ a book by {\underline{\hspace{10pt}}} ] on the table?](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-65f90f98971fc5d44d3aca90a65cf667_l3.png)

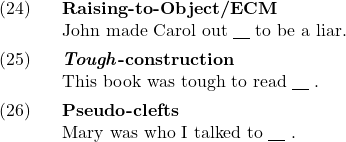

The purpose of identifying a particular signature for A’-movement is that it helps us identify kinds of movement when we encounter new data. For instance, the following sentences all contain gaps/unpronounced elements.

If we want to understand the syntax of such sentences, then we need to figure out how that gap came into existence. We can apply the tests above (including a test for unbounded dependendencies) to determine if there’s movement, and what kind of movement it is.

Islandhood tests can be tricky to conceptualize. Here is an analogy that might (or might not) help.

Suppose that in your degree program, there are classes which you are required to attend in-person, and there are classes which you are required to attend over Zoom. Now suppose one of your roommates contracts Ebola and is very sick. Because you’ve been in contact with your roommate, you are required by law to quarantine at home. You can’t leave your house. (Your roommate will eventually make a miraculous recovery.)

- If you go to an in-person class, you’d be breaking quarantine. That’s bad—it’s illegal and dangerous. So you just can’t attend in-person classes while you’re in quarantine.

- But you can still attend Zoom classes. That is, you can only “leave” your house by via some other way, like the internet.

Here’s the analogy explained:

- The classes are different syntactic constructions. Some of them involve “movement” (i.e., attending class in-person) and some of them don’t (i.e., Zoom classes).

- Sometimes, you’re blocked from leaving your house. That is, you can’t “move.” So being in quarantine is the same as being in an island. In the analogy, that means you can’t attend in-person classes; you can’t leave quarantine. In syntax, that means that you can’t participant in certain syntactic constructions; you can’t move out of an island.

- But other syntactic constructions don’t require you to move, you can participate via some other way of getting out of the house, like over Zoom. In syntactic terms, there are ways other than movement to “leave” an island—but it won’t be “physical” movement.

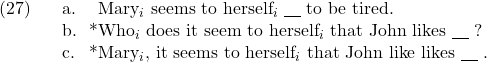

A-movement diagnostics

We’ve focused here on a few island constraints, which diagnose A’-movement. There are ways to diagnose A-movement as well. The clearest way to diagnose A-movement is to use binding. A-movement creates new binding dependencies; A’-movement doesn’t.

When you raise to subject across seem, the resulting movement can feed Condition A: the subject can now antecede an anaphor. A’-movement does not permit this. If I question or topicalize some constituent, it cannot antecede an anaphor.

Exercises

- In this book, the terms "gap" and "trace" are functionally interchangeable. Though it should be noted that "gap" is not a formal term. ↵

- There are a few different complementizers in Irish, which interact with A'-movement in interesting ways. The superscript "L" indicates one type of complementizer. ↵

Movement of a wh-word: who, what, how, why, where, when, etc. We often use "wh-movement" as a shorthand for "A'-movement." However, while all wh-movement is A'-movement, not all A'-movement is wh-movement.

A version of the complementizer used in questions.

Yes/No questions, or questions that can be answered either "yes" or "no."

The condition of Binding Theory that stipulates that "An anaphor must be bound in its binding domain."

The condition of binding theory that governs R-expressions. "R-expressions cannot be bound."

An instance of an unpronounced constituent. For example, in "Tegan called Joanna, and Sam did, too," there is an unpronounced VP [ called Joana ] in the second half of the sentence.