10

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Explain the difference between racial and ethnic groups, and outline the sides of the debate over the idea that race is biologically derived versus a social construct.

- Distinguish between minority and dominant group status and discuss how and why minority groups are established.

- Explain stereotyping, prejudice and individual and institutional discrimination and discuss how stereotyping and prejudice help to promote and perpetuate social inequality between groups.

- Outline the patterns of intergroup relations and provide examples of each.

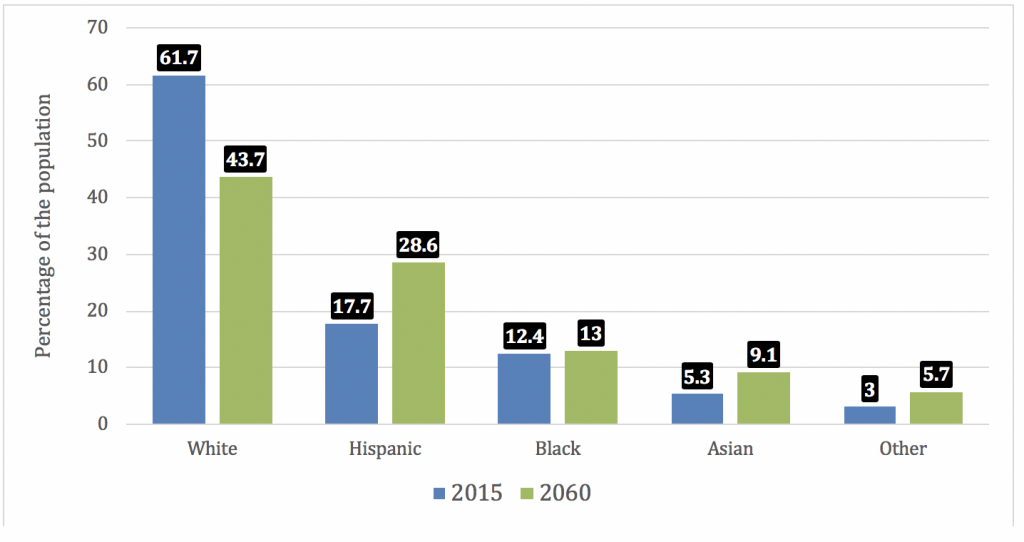

- Describe the current and future projections for the racial-ethnic makeup of the U.S.

10.1 Racial and Ethnic Relations

Race and ethnicity have torn at the fabric of American society ever since the time of Christopher Columbus, when at least 1 million Native Americans were thought to have populated what would become the United States. By 1900, their numbers had dwindled to about 240,000, as hundreds of thousands were either killed by white settlers and U.S. troops, died from disease contracted from people with European backgrounds or were killed in inter-tribal conflict. Scholars have said that this mass killing of Native Americans amounted to genocide (Wilson, 1999).

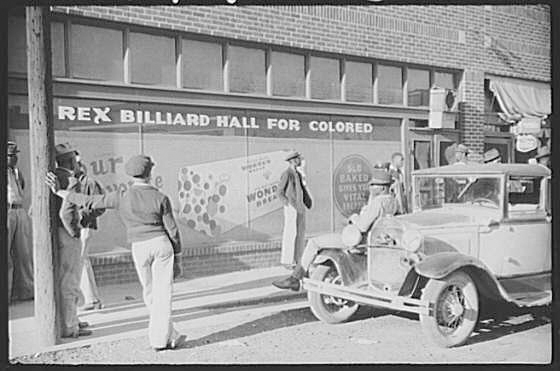

Black people obviously also have a history of maltreatment that began during the colonial period, when Africans were forcibly transported from their homelands to be sold and abused as slaves in the Americas. During the 1830’s, white mobs attacked Black people in cities throughout the nation, including Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Buffalo and Pittsburgh. This violence led Abraham Lincoln to lament about “savage mobs” and their “increasing disregard for law which pervades the country” (Feldberg, 1980, p. 4). The mob violence stemmed from a “deep-seated racial prejudice… in which whites saw blacks as ‘something less than human’” (Brown, 1975, p. 206) and continued well into the 20th century, when whites attacked Black people in many cities, with at least seven anti-black riots occurring in 1919 alone that left dozens dead. Meanwhile, an era of Jim Crow racism in the South (1870’s – 1960’s) led to the lynching of thousands of Black people and segregation in all facets of life (Litwack, 2009).

Blacks were not the only targets of native-born white mobs back then (Dinnerstein & Reimers, 2009). As immigrants from Ireland, Italy, Eastern Europe, Mexico, and Asia came to the United States during the 19th and early 20th centuries, they, too, were beaten, denied jobs, and otherwise mistreated. During the 1850s, mobs beat and sometimes killed Catholics in cities such as Baltimore and New Orleans, as nativism rose in response to increases in immigration of Catholics from Ireland, Germany, Italy and Eastern Europe. Similarly, during the 1870s, whites rioted against Chinese immigrants in California and other states and many Mexicans were attacked and/or lynched in California and Texas during this period.

Not surprisingly, scholars have written about U.S. racial and ethnic prejudice ever since the period of slavery. In 1835, the great social observer Alexis de Tocqueville (1835/1994) despaired that whites’ prejudice would make it impossible for them to live in harmony with Black people. Decades later, W. E. B. Du Bois (1903/1968, p. vii), one of the first sociologists to study race observed in 1903 that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line” and cited example after example of economic, social and legal discrimination against Black people.

Nazi racism in the 1930s and 1940s helped awaken Americans to the evils of prejudice in their own country. As WWII ended, after fighting against fascism in Europe and Asia, Black and Japanese American soldiers returned home to a segregated American society and their families who had been interned in relocation camps during the war, respectively.

Against this backdrop, a monumental two-volume work by Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal (1944) attracted much attention when it was published. The book, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, documented the various forms of discrimination facing blacks at the time. The “dilemma” referred to in the book’s title was the conflict between the American democratic values of egalitarianism, liberty and justice for all and the harsh reality of prejudice, discrimination, and lack of equal opportunity.

Despite finding ample evidence of extreme inequality, Myrdal expressed optimism that integration and peace were feasible. However, the system of legal segregation was not dismantled until the civil rights movement won its major victories in the 1950’s and 1960s. Even after segregation ended, improvement in other areas was slow. Thus in 1968, the so-called Kerner Commission (1968, p. 1), appointed by President Lyndon Johnson in response to urban riots, warned in a famous statement, “Our nation is moving toward two societies, one Black, one white—separate and unequal.” Despite this warning, and despite the civil rights movement’s successes, 30 years later writer David K. Shipler (1997, p. 10) felt compelled to observe that there is “no more intractable, pervasive issue than race” and that when it comes to race, we are “a country of strangers.” Sociologists and other social scientists have warned since then that the conditions of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color) have actually been worsening (Massey, 2007; W. J. Wilson, 2009). Despite the historic election of Barack Obama in 2008, race and ethnicity remain an “intractable, pervasive issue.” Indeed, it would be accurate to say, to paraphrase Du Bois, that “the problem of the 21st century is the problem of the color line.” Evidence of this continuing problem appears in much of the remainder of this chapter.

10.2 The Meaning of Race, Ethnicity and Minority Status

To understand this “problem of the color line” further, we need to take a critical look at the very meaning of race and ethnicity. These concepts may seem easy to define initially but are much more complex than their definitions suggest.

Race

Let’s start first with race, which refers to a category of people who share certain physical characteristics, such as skin color, facial features and stature. Many people incorrectly assume race is a biological category when it is in fact a socially constructed concept. , a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is (Berger & Luckmann, 1963). In this view race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it. For more than 300 years, or ever since European colonization, race has indeed served as a primary means of differentiating between and stratifying groups and has been used as an justification for slavery and other mistreatment of BIPOC, however, recent research in genetics has proven that race is not a biological reality. According to Vence Bonham, J.D. of the National Human Genome Research Institute, “Race is a concept without a generally agreed upon definition. Race has been documented as a concept developed in the 18th century to divide humans into groups often based on physical appearance, social, and cultural backgrounds. Race has been used historically to establish a social hierarchy and to enslave humans. Racial groups have no defined boundaries, but have a blurry and imprecise relationship with human genetic variation and population groups across the world. I like Professor Audrey Smedley’s definition. She states, “Race is a culturally structured systematic way of looking at, perceiving, and interpreting reality.” The director of the Human genome project has also stated “Those who wish to draw precise racial boundaries around certain groups will not be able to use science as a legitimate justification.” People from different races are more than 99.9% the same in their DNA (Begley, 2008). To turn that around, less than 0.1% of all the DNA in our bodies accounts for the physical differences among people that we associate with racial differences. In terms of DNA, then, people with different racial backgrounds are far more similar than dissimilar.

Although people certainly do differ in the many physical features that led to the development of such racial categories, we often see more physical differences within a race than between races. For example, some people we call “white” (or European), such as those with Scandinavian backgrounds, have very light skin, while others, such as those from some Eastern European backgrounds, have much darker skin. In fact, some “whites” have darker skin than some “Blacks.” Some whites have very straight hair while others have very curly hair; some have blonde hair and blue eyes, while others have dark hair and brown eyes. Because of interracial reproduction going back to the days of slavery, Black people also differ in the darkness of their skin and in other physical characteristics. In fact, it is estimated that about 80% of Black people have some white (i.e., European) ancestry; 50% of Mexican Americans have European and/or Native American ancestry; and 20% of whites have African or Native American ancestry. If clear racial differences ever existed hundreds or thousands of years ago (and many scientists doubt such differences ever existed), these differences have become increasingly blurred.

Even if we acknowledge that people differ in the physical characteristics we associate with race, modern evolutionary evidence reminds us that we are all, really members of one human race. According to evolutionary theory, homo sapiens evolved 200,000+ years ago in sub-Saharan Africa. As people migrated around the world over the millennia, natural selection took over. It favored dark skin for people living in hot, sunny climates (i.e., near the equator), because the heavy amounts of melanin that produce dark skin protect against severe sunburn, cancer, and other problems. By the same token, natural selection favored light skin for people who migrated farther from the equator to cooler, less sunny climates, because dark skins there would have interfered with the production of vitamin D (Stone & Lurquin, 2007). Evolutionary evidence thus reinforces the common humanity of people who differ in the rather superficial ways associated with their appearances: we are one human species composed of people who happen to look different.

Another way we know and knew even before the Human Genome project that race is a social construct is that an individual or a group of individuals is often assigned to a race on arbitrary or even illogical grounds. A century ago, for example, Irish, Italians, and Eastern European Jews who immigrated to the United States were not regarded as white once they reached the United States but rather as a different, inferior (if unnamed) race (Painter, 2010). The belief in their inferiority helped justify the harsh treatment they suffered in their new country. Today, of course, we call people from all three backgrounds white or European.

In this context, consider someone in the United States who has a white parent and a Black parent. What race is this person? American society usually calls this person Black or African American, and the person may adopt the same identity (as does Barack Obama, who had a white mother and African father). But where is the logic for doing so? This person is as much white as Black in terms of parental ancestry. Or consider someone with one white parent and another parent who is the child of one Black parent and one white parent. This person thus has three white grandparents and one Black grandparent. Even though this person’s ancestry is thus 75% white and 25% Black, she or he is likely to be considered black in the United States and may well adopt this racial identity. This practice reflects the “one-drop rule” practiced in the United States that defines someone as Black if she or he has at least one Black ancestor and that was used in the antebellum South to keep the slave population as large as possible (Wright, 1993). Yet in many Latin American nations, this person would be considered white. In Brazil, the term Black is reserved for someone with no European (white) ancestry at all. If we followed this practice in the United States, about 80% of the people we call “Black” would now be called “white.” With such arbitrary designations, race is a social category rather than a biological one. Furthermore, during Spanish colonization, someone in Latin America could purchase a certificate of whiteness if they were not white, but had money.

Another way we know that race is a social construct is because people do not fit neatly into racial categories. For example, the famous golfer Tiger Woods is typically labeled an Black by the news media but in fact his ancestry is one-quarter Chinese, one-quarter Thai, one-quarter white, one-eighth Native American and one-eighth Black (Leland & Beals, 1997). Another example, former President Barack Obama has an African father and a white mother. Although his ancestry is equally Black and white, Obama considers himself an Black and African American. Many Black Americans do not prefer the term African American, but the term is appropriate for President Obama because his father was originally from the continent of Africa. According to Greg Carr, an associate professor and the chair of Howard University’s Department of Afro-American Studies, “When you say ‘Black’ there is no ambiguity. It’s like a fist which may be why some white people don’t like to use it because it’s like ‘Can I see Black?'” but not acknowledging we see race is like saying there is something so bad about being Black that we cannot even say it and he says, “Not only is this something not to be ashamed of, it is something to be embraced.” A recent poll conducted via various social media outlets including Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter showed that most respondents prefer to be called as Black before African-American or a Person of Color. Other terms that are no acceptable include Negro and colored. The term Negro was created to identify Black slaves as property and the term colored was created to dehumanize non-slave Black people. https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/local/black-history/black-vs-african-american-the-complex-conversation-black-americans-are-having-about-identity-fortheculture/65-80dde243-23be-4cfb-9b0f-bf5898bcf069.

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social construction of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of slaves lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other whites with slaves. As it became difficult to tell who was “Black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having black ancestry would go to court to prove they were white in order to avoid enslavement or other problems (Staples, 1998). Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to white. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and a slave and thereafter had only white ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “Black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was black). Phipps had always thought of herself as white and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially black because she had one black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 1994).

Although race is a social construction, it is also true that things perceived as real are real in their consequences. Because people do perceive race as something real, it has real consequences. Even though so little of DNA accounts for the physical differences we associate with racial differences, that low amount leads us not only to classify people into different races but to treat them differently—and, more to the point, unequally—based on their classification. Yet modern evidence shows there is little, if any, scientific basis for the racial classification that is the source of so much inequality.

Ethnicity

Like race, ethnicity is a socially constructed concept used to categorize people. Ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences or from common national or regional backgrounds, that make groups different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a group with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; with relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and with some sense of identity of belonging to the group. So conceived, the terms ethnicity and ethnic group avoid the biological connotations of the terms race and racial group and the biological differences these terms imply. At the same time, the importance we attach to ethnicity has important consequences for how we are treated.

Because ethnicity is socially constructed, people do not fit neatly into defined categories. Two ethnic groups that are often discussed interchangeable, but are in reality different are Hispanic and Latin American (also referred to as Latino, Latina, Latinx). Hispanic by definitions means of Spanish descent. This includes having ancestors from Spain and any part of the world that was colonized by Spain. Hispanic therefore is based on a specific element of culture, language. Latin American, (Latino, Latina, Latinx), on the other hand, is based on being from the region known as Latin American which includes the Caribbean, Central and South America. This does not include Spain as it is in Europe. Latin America also includes other nations in the region that are not Spanish speaking such as Brazil, Guyana, and Belize.

Another aspect of ethnicity and ethnic group membership is the conflict they create among people of different ethnic groups. History and current practice indicate that it is easy to become prejudiced against people with different ethnicities from our own. Much of the rest of this chapter looks at the prejudice and discrimination operating today in the United States against people whose ethnicity is not white and European. Globally, ethnic conflict continues to rear its ugly head. The 1990s and 2000s were rife with incidences of “ethnic cleansing” and pitched battles among ethnic groups in Eastern Europe, Africa, and elsewhere. Our ethnic heritages shape us in many ways and fill many of us with pride, but they also are the source of much conflict, prejudice, and even hatred.

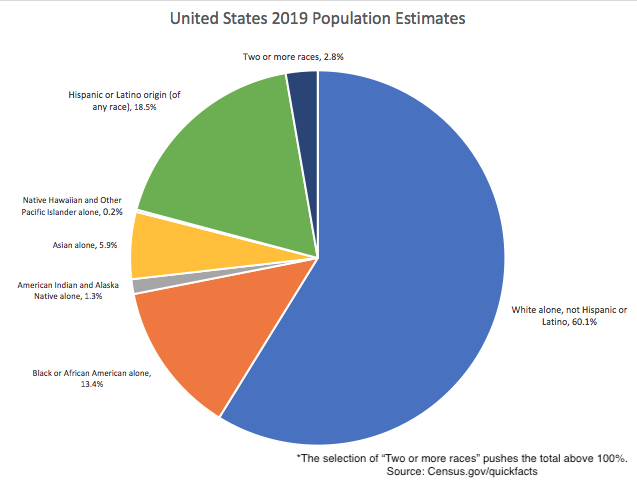

Figure 10.1 Racial/Ethnic Compositions of the United States, 2019 Estimates

Minority and Dominant Groups

Once established, it is common for racial and ethnic groups to be stratified, where one group holds dominant status and other groups minority status. Sociologist Louis Wirth (1945) defined a minority group as “any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination.” The term minority connotes discrimination, and in its sociological use, the term can be used interchangeably with the term minority. These definitions correlate to the concept that the dominant group is that which holds the most power in a given society, while subordinate groups are those who lack power compared to the dominant group. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

Note that being a numerical minority is not a characteristic of being a minority group; sometimes larger groups can be considered minority groups due to their lack of power. It is the lack of power that is the predominant characteristic of a minority, or subordinate group. For example, consider apartheid in South Africa, in which a numerical majority (the black inhabitants of the country) were exploited and oppressed by the white population, who made up approximately 15% of the population. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

According to Charles Wagley and Marvin Harris (1958), a minority group is distinguished by five characteristics: (1) unequal treatment and less power over their lives, (2) distinguishing physical or cultural traits like skin color or language, (3) involuntary membership in the group, (4) awareness of subordination, and (5) high rate of in-group marriage. Additional examples of minority groups might include the LGBTQIA community, religious practitioners whose faith is not widely practiced where they live, and people with disabilities. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

Forms of Contact

Racial and ethnic groups typically attain dominant or minority status when groups that were formerly separated territorially come into contact with one another (Marger, 2015). Contact between groups can take different forms and the form of contact will determine the long-term status of and interactions between groups. The current U.S. racial and ethnic hierarchy was established in this fashion.

There are three broad forms of contact between racial and ethnic groups, including conquest, annexation and immigration. Conquest is a form of contact that occurs when conflict arises between formerly separated groups, resulting in one group conquering and coming to dominate the other (Marger, 2015). During the period of European colonization, for instance, Europeans conquered and assigned minority status to groups living in the Americas, African, Asia, Australia and the Pacific Islands. Native Americans became minorities in this period through this process, and continue to hold this status today, centuries later.

Annexation is similar to conquest, in that it often results from conflict. It is distinct though because it involves a legal process that transfers territory, typically in the form of a treaty, between groups. For instance, following the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo forced the Mexican government to cede 529,000 square miles, or roughly ½ of the Mexican Republic, to the United States. While Mexicans living in this annexed territory were given rights to U.S. citizenship, Mexicans also became a minority group, and continue to suffer the harsh consequences of this status.

Immigration also results in bringing diverse racial and ethnic groups together. There are two forms of immigration in this respect: forced immigration and voluntary immigration (Marger, 2015). Africans brought to the Americas as a part of the trans-Atlantic slave trade are a good example of involuntary immigrants. Groups forced to move to a new society are established as a subordinate group through this process. Conquest, annexation and involuntary immigration are the three forms of contact that result in the greatest inequality and long-term conflict and antagonism between minority and dominant groups. This fact is evidenced by our earlier review of economic, educational, political and health disparities that continue to disproportionately impact Black, Native American and Hispanic Americans centuries after their initial contact with white Americans.

Immigrants who voluntarily move to another society who differ in race or ethnicity from the dominant group may be assigned minority status upon arrival and are subordinated as a result. However, the subordination of these groups will often ease over several generations, resulting in their rise in status within the racial-ethnic hierarchy. This is particularly true for immigrants who are more physically or culturally similar to the dominant group, such as Irish, Italian and Eastern European Americans. As discussed earlier in this chapter, these ethnic groups were initially painted as racially distinct from and inferior to Americans of British descent, but by the 3rd and 4th generations, these ethnic groups underwent assimilation and experienced significant social mobility.

Once dominant-minority relations are established, ideology forms to explain, justify and perpetuate this hierarchy. For instance, beginning in the 1600’s a field of pseudoscience, referred to by critics as scientific racism, was established in which theories relating to racial hierarchy were tested. Researchers conducted studies to measure skull size and shape as well as other supposed physical differences between racial groups and inevitably found that the physical differences between groups aligned with the position of the group, i.e., “superior” physical qualities were found in the dominant group, while “inferior” qualities characterized racial and ethnic minority groups, thus justifying rank and the resultant inequalities. Similarly, as discussed in the next section, positive and negative stereotypes arise in relation to groups and their position. Positive stereotypes justify the high status of dominant groups (Group X is hard working and smart), while negative stereotypes disparage and justify the low status of minority groups (Group Y is lazy and criminal).

10.3 Stereotypes and Prejudice

Let’s examine racial and ethnic stereotypes and prejudice further and then turn to discrimination. Prejudice and discrimination are often confused, but the basic difference between them is this: prejudice is an attitude, while discrimination is a behavior. More specifically, racial and ethnic prejudice refers to a set of negative attitudes, beliefs, and judgments about groups, and about individual members of those groups, because of their race and/or ethnicity. A closely related concept is racism, or the belief that certain racial or ethnic groups are biologically or culturally inferior to one’s own. Prejudice and racism are often based on racial and ethnic stereotypes, or simplified, mistaken generalizations about people because of their race and/or ethnicity, which are not tested against reality and which are learned second-hand. Stereotypes may be positive (usually about one’s in-group, such as when women suggest they are less likely to complain about physical pain) but are often negative (usually toward out-groups, such as when members of a dominant racial group suggest that a subordinate racial group is less intelligent or lazy). In either case, the stereotype is a generalization that doesn’t take individual differences into account. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

The above indicates that stereotypes arise to disparage and justify the subordination of minority groups. New stereotypes are, in fact, rarely created; rather they are recycled from subordinate groups that have assimilated into society and are reused to describe newly subordinate groups (a phenomenon known as stereotype interchangeability). (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1). An example of this can be seen in comparing stereotypes of East Asians in the 1800’s with stereotypes of Hispanic and Muslim Americans today. The term “Yellow Peril” from the late 1800’s was based upon the belief that East Asian immigrants were culturally and politically tied to their countries of origin and unable to assimilate, and thus their immigration in large numbers to the U.S. would not only result in cultural competition with Anglo-Americans but would inevitably destroy their way of life. As Asian Americans experienced upward mobility in the U.S., the perception of this group has changed. Rather than being perceived as threatening and unassimilable, Asian Americans are now stereotyped as a model minority, characterized by high levels of education and prominence in white-collar jobs. The old “Yellow Peril” stereotype has been recycled, and in the 2000’s we have seen a rise in similar stereotypes, such as the perception that Hispanic Americans are an invading force here to change the very nature of U.S. culture, and of Muslim Americans who are discussed as being closely tied to their countries of origin and working to impose their religious belief and political structures on unsuspecting U.S. communities.

Explaining Prejudice

Where do racial and ethnic prejudices come from? Why are some people more prejudiced than others? Scholars have tried to answer these questions at least since the 1940s, when the horrors of Nazism were still fresh in people’s minds. Theories of prejudice fall into two camps, social-psychological and sociological. We will look at social-psychological explanations first and then turn to sociological explanations. We will also discuss distorted mass media treatment of various racial and ethnic groups.

Social-Psychological Explanations

One of the first social-psychological explanations of prejudice centered on the authoritarian personality (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswick, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950). According to this view, authoritarian personalities develop in childhood in response to parents who practice harsh discipline. Individuals with authoritarian personalities emphasize such things as obedience to authority, a rigid adherence to rules, and low acceptance of people (outgroups) not like oneself. Many studies find strong racial and ethnic prejudice among such individuals (Sibley & Duckitt, 2008). But whether their prejudice stems from their authoritarian personalities or instead from the fact that their parents were probably prejudiced themselves remains an important question.

Another early and still popular social-psychological explanation is called frustration or scapegoat theory (Dollard, Doob, Miller, Mowrer, & Sears, 1939). In this view, individuals who experience various kinds of problems become frustrated and blame their troubles on low status groups (e.g., racial, ethnic, and religious minorities). These minorities are thus scapegoats for the real sources of people’s misfortunes.

In the real world, scapegoating at a mass level has been quite common. In medieval Europe, Jews were commonly blamed and persecuted when economic conditions were bad or when war efforts were failing. After the bubonic plague broke out in 1348 and eventually killed more than one-third of all Europeans, Jews were blamed either for deliberately spreading the plague or for angering God because they were not Christian. When Germany suffered economic hardship after World War I, Jews again proved a convenient scapegoat, and anti-Semitism helped fuel the rise of Hitler and Nazism (Litvinoff, 1988). Similarly, in the U.S., nativism (anti-immigrant sentiment) and xenophobia (fear and hatred of outgroups) commonly arise during periods of significant social change and economic decline.

Sociological Explanations

Sociological explanations of prejudice incorporate some of the principles and processes discussed in previous chapters. One popular explanation emphasizes conformity and socialization (also called social learning theory). In this view, people who are prejudiced are merely conforming to the culture in which they grow up, and prejudice is the result of socialization from agents of socialization. Supporting this view, studies have found that people tend to become more prejudiced when they move to areas where people are very prejudiced and less prejudiced when they move to locations where people are less prejudiced (Aronson, 2008).

A theory that piggybacks on social learning theory is contact theory. While social learning theory helps us to understand the relationship between socialization and prejudice, the view of contact theorists is that prejudice arises in societies where institutional segregation and social inequality are paired. Segregation in schools, workplaces and communities limit contact between members of diverse groups. Limited contact results in little to no opportunity to develop professional and personal relationships with members of other racial and ethnic groups, which means our chances of confronting and testing the stereotypes we hold is limited. Theorists who promote the contact theory argue that prejudice will be reduced when diverse groups are brought together within the social institutions of society (e.g., school desegregation or workplace integration). However, in order for this integration to effectively reduce prejudice, the groups being brought together must have equal status, otherwise power differentials will keep groups apart, even within integrated institutions, and only serve to perpetuate prejudice.

A third sociological explanation emphasizes economic and political competition and is commonly called group threat theory (Quillian, 2006; Hughes & Tuch, 2003). In this view prejudice arises from competition over jobs and other resources and from disagreement over various political issues. When groups vie with each other over these matters, they often become hostile toward each other. Amid such hostility, it is easy to become prejudiced toward the group that threatens your economic or political standing. A popular version of this basic explanation is Susan Olzak’s (1992) ethnic competition theory, which holds that ethnic prejudice and conflict increase when two or more ethnic groups find themselves competing for jobs, housing, and other goals.

As might be clear, the competition explanation is the macro or structural equivalent of the frustration/scapegoat theory already discussed. Much of the white mob violence discussed earlier stemmed from whites’ perception that the groups they attacked threatened their jobs and other aspects of their lives. Thus, lynchings of Black people in the South increased when the Southern economy worsened and decreased when the economy improved (Tolnay & Beck, 1995). Similarly, white mob violence against Chinese immigrants in the 1870s began after the railroad construction that employed so many Chinese immigrants slowed and the Chinese began looking for work in other industries. Whites feared that the Chinese would take jobs away from white workers and that their large supply of labor would drive down wages. Their fear prompted the passage by Congress of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 that prohibited Chinese immigration (Dinnerstein & Reimers, 2009). Several nations today, including the United States, have experienced increased anti-immigrant prejudice because of the influx of immigrants and refugees onto their shores coupled with a growing gap between rich and poor and economic upheaval (Bauer, 2009). We return to anti-immigrant prejudice later in this chapter.

The Changing Nature of Prejudice

Although racial and ethnic prejudice still exists in the United States, its nature has changed during the past half-century. Studies of these changes focus on whites’ perceptions of Blacks. Back in the 1940’s and before, an era of overt racism prevailed. This racism involved blatant bigotry, firm beliefs in the need for segregation, and the view that Black people were biologically inferior to whites. This form of racism is referred to as biological racism. In the early 1940’s, more than half of white people surveyed favored segregation in public transportation, more than two-thirds favored segregated schools and more than half thought whites should receive preference in employment hiring (Schuman, Steeh, Bobo & Krysan, 1997).

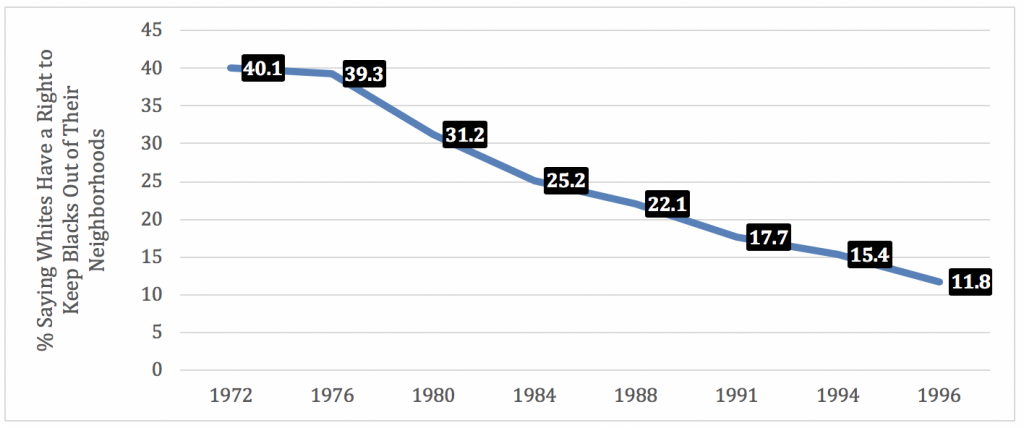

Since this time, the degree of overt racism has waned. Few believe today in the biological inferiority or superiority of racial or ethnic groups, and few favor legal segregation. As just one example, Figure 10.2 “Changes in Support by Whites for Segregated Housing, 1972 – 1996” shows that whites’ support for segregated housing declined dramatically from about 40% in the early 1970s to about 12% in 1996. So few whites now support legal segregation that the GSS stopped asking about segregated housing after 1996.

Figure 10.2 Changes in Support by Whites for Segregated Housing, 1972–1996

Despite these changes, several scholars say that overt racism has been replaced by a subtle form of racial prejudice, termed cultural racism, that avoids notions of biological inferiority (Quillian, 2006; Bobo, Kluegel, & Smith, 1997, p. 15; Sears, 1988). Instead, it involves stereotypes about minority groups, a belief that their higher rates of poverty are due to their cultural inferiority, and opposition to government policies to help them. In effect, this new form of prejudice blames minorities themselves for their low socioeconomic standing and involves such beliefs that they simply do not want to work hard. As Lawrence Bobo and colleagues (Bobo, Kluegel, & Smith, 1997, p. 31) put it, “Blacks are still stereotyped and blamed as the architects of their own disadvantaged status.” They note that these views lead whites to oppose government efforts to help to alleviate the condition of poverty for minorities.

10.4 Discrimination

Often racial and ethnic prejudice lead to discrimination against the subordinate racial and ethnic groups in a given society. Discrimination in this context refers to the arbitrary denial of rights, privileges, and opportunities to members of these groups. The use of the word arbitrary emphasizes that these groups are being treated unequally not because of their lack of merit but because of their race and ethnicity.

Usually prejudice and discrimination go hand-in-hand, but Robert Merton (1949) stressed that this is not always the case. Sometimes we can be prejudiced and not discriminate, and sometimes we might not be prejudiced and still discriminate. Table 10.1 “The Relationship Between Prejudice and Discrimination” illustrates his perspective. The top-left cell and bottom-right cells consist of people who behave in ways we would normally expect. The top-left one consists of “active bigots,” in Merton’s terminology, people who are both prejudiced and discriminatory. An example of such a person is the white owner of an apartment building who dislikes BIPOC and refuses to rent to them. The bottom-right cell consists of “all-weather liberals,” as Merton called them, people who are neither prejudiced nor discriminatory. An example would be someone who holds no stereotypes about the various racial and ethnic groups and treats everyone the same regardless of her/his background.

Table 10.1 The Relationship Between Prejudice and Discrimination

|

|

Prejudiced? |

||

|

Yes |

No |

||

|

Discriminates? |

Yes |

Active Bigots

|

Fair-weather Liberals |

|

No |

Timid Bigots

|

All-weather Liberals |

|

Source: Adapted from Merton, R. K. (1949). Discrimination and the American creed. In R. M. MacIver (Ed.), Discrimination and national welfare (pp. 99–126). New York, NY: Institute for Religious Studies.

The remaining two cells of the table are the more unexpected ones. On the bottom left, we see people who are prejudiced but who nonetheless do not discriminate; Merton called them “timid bigots.” An example would be white restaurant owners who do not like BIPOC but still serve them anyway because they want their business or are afraid of being sued if they do not serve them. At the top right, we see “fair-weather liberals”: people who are not prejudiced but who still discriminate. An example would be white store owners in the South during the segregation era who thought it was wrong to treat Blacks worse than whites but who still refused to sell to them because they were afraid of losing white customers.

Individual Discrimination

The discussion so far has centered on individual discrimination, or discrimination that individuals practice in their daily lives, usually because they are prejudiced but sometimes even if they are not prejudiced. Examples of individual discrimination abound today. Joe Feagin (1991), a former president of the American Sociological Association, documented such discrimination when he interviewed middle-class Blacks about their experiences. Many of the people he interviewed said they had been refused service, or at least received poor service, in stores or restaurants. Others said they had been harassed by the police, and even put in fear of their lives, just for being black. Feagin concluded that these examples are not just isolated incidents but rather reflect the larger racism that characterizes U.S. society.

Similarly, much individual discrimination occurs in the workplace, as sociologist Denise Segura (1992) documented through interviews with Mexican American women working in white-collar jobs at a public university in California. More than 40% of the women said they had encountered workplace discrimination based on their ethnicity and/or gender and they attributed their treatment to stereotypes held by their employers and coworkers.

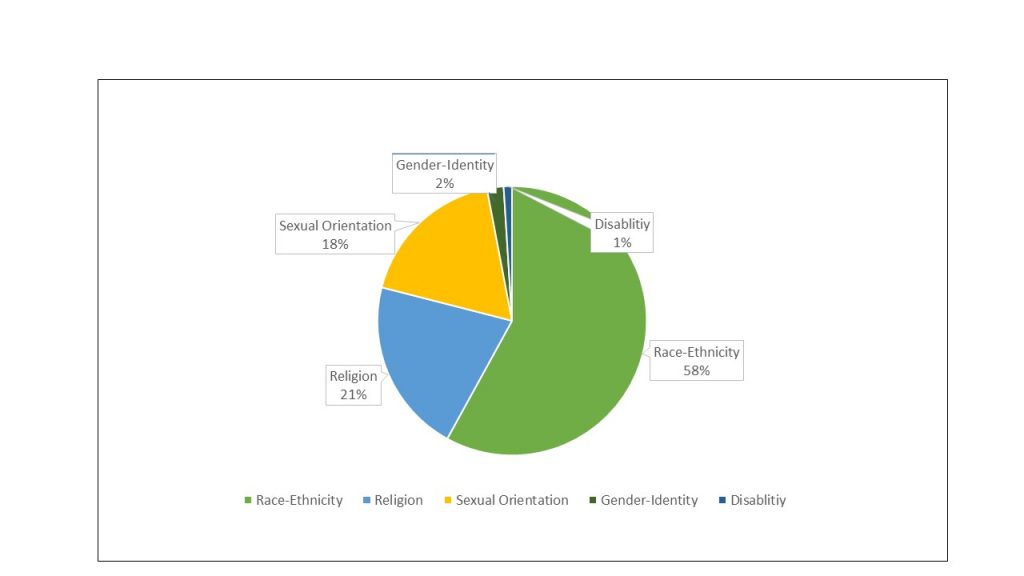

One particularly insidious form of individual discrimination in hate or bias crime. In 2016, there were 6,063 single-bias hate crimes committed in the U.S. (FBI, 2017). Of these hate crimes, the majority were motived by race/ethnicity/ancestry bias. Figure 10.3 “Hate Crimes in the U.S., Single-Bias Incidents, 2016” demonstrates the different groups targeted in such crimes. Of the 57.5% of hate crimes targeting people due to race-ethnicity, half of these crimes specifically targeted Black people (FBI, 2017).

Figure 10.3 Hate Crimes in the U.S., Single-Bias Incidents, 2016

Institutional Discrimination

Individual discrimination is important to address, as it is consequential in U.S. society today. institutional discrimination is discrimination that pervades the practices of whole institutions, such as housing, medical care, law enforcement, employment, and education. This type of discrimination affects large numbers of individuals simply because of their race or ethnicity. Sometimes institutional discrimination is also based on sexual orientation, gender, disability and/or other characteristics.

In the area of race and ethnicity, institutional discrimination often stems from prejudice and is intentional, as was certainly true in the South during the period of segregation. However, just as individuals can discriminate without being prejudiced, so can institutions when they engage in practices that seem to be racially neutral but in fact have a discriminatory effect. Consider height requirements for police. Before the 1970s, police forces around the United States commonly had height requirements, say 5 feet 10 inches. As women began to want to join police forces in the 1970s, many found they were too short. The same was true for people from some racial/ethnic backgrounds, such as Latinos, whose stature is smaller on the average than that of non-Latino whites.

This gender and ethnic difference is not, in and of itself, discriminatory as the law defines the term. The law allows for bona fide (good faith) physical qualifications for a job. As an example, we would all agree that someone has to be able to see to be a school bus driver; sight therefore is a bona fide requirement for this line of work. Thus, even though people who are blind cannot become school bus drivers, the law does not consider such a physical requirement to be discriminatory.

But were the height restrictions for police work in the early 1970s bona fide requirements? Women and members of certain ethnic groups challenged these restrictions in court and won their cases, as it was decided that there was no logical basis for the height restrictions then in effect. The courts concluded that a person did not have to be 5 feet 10 inches to be an effective police officer. In response to these court challenges, police forces lowered their height requirements, opening the door for many more women, Latino men, and others to join police forces (Appier, 1998).

Institutional discrimination affects the life chances of BIPOC in many aspects of life today. To illustrate this, we turn to some examples of institutional discrimination that have been the subject of government investigation and scholarly research.

Health Care Discrimination

When looking at the social epidemiology of the United States, it is hard to miss the disparities among races. The discrepancy between Black and white Americans shows the gap clearly; in 2008, the average life expectancy for white males was approximately five years longer than for black males: 75.9 compared to 70.9. An even stronger disparity was found in 2007: the infant mortality, which is the number of deaths in a given time or place, rate for Blacks was nearly twice that of whites at 13.2 compared to 5.6 per 1,000 live births (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). According to a report from the Henry J. Kaiser Foundation (2007), Black people also have higher incidence of several other diseases and causes of mortality, from cancer to heart disease to diabetes. In a similar vein, it is important to note that ethnic minorities, including Mexican Americans and Native Americans, also have higher rates of these diseases and causes of mortality than whites.

Lisa Berkman (2009) notes that this gap started to narrow during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s, but it began widening again in the early 1980s. What accounts for these perpetual disparities in health among different ethnic groups? Much of the answer lies in the level of healthcare that these groups receive. The National Healthcare Disparities Report (2010) shows that even after adjusting for insurance differences, racial and ethnic minority groups receive poorer quality of care and less access to care than dominant groups. The Report identified these racial inequalities in care:

- Black Americans, American Indians, and Alaskan Natives received inferior care than White Americans for about 40 percent of measures.

- Asian ethnicities received inferior care for about 20 percent of measures.

- Among whites, Hispanic whites received 60 percent inferior care of measures compared to non-Hispanic whites (Agency for Health Research and Quality 2010). When considering access to care, the figures were comparable.

(OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

Several studies use hospital records to investigate whether BIPOC receive optimal medical care, including coronary bypass surgery, angioplasty, and catheterization. After taking the patients’ medical symptoms and needs into account, these studies find that Black patients are much less likely than whites to receive the procedures just listed, irrespective of their social class status (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003). In a novel way of studying race and cardiac care, one study performed an experiment in which several hundred doctors viewed videos of Black and white patients, all of whom, unknown to the doctors, were actors. In the videos, each “patient” complained of identical chest pain and other symptoms. The doctors were then asked to indicate whether they thought the patient needed cardiac catheterization. The Black patients were less likely than the white patients to be recommended for this procedure (Schulman et al., 1999).

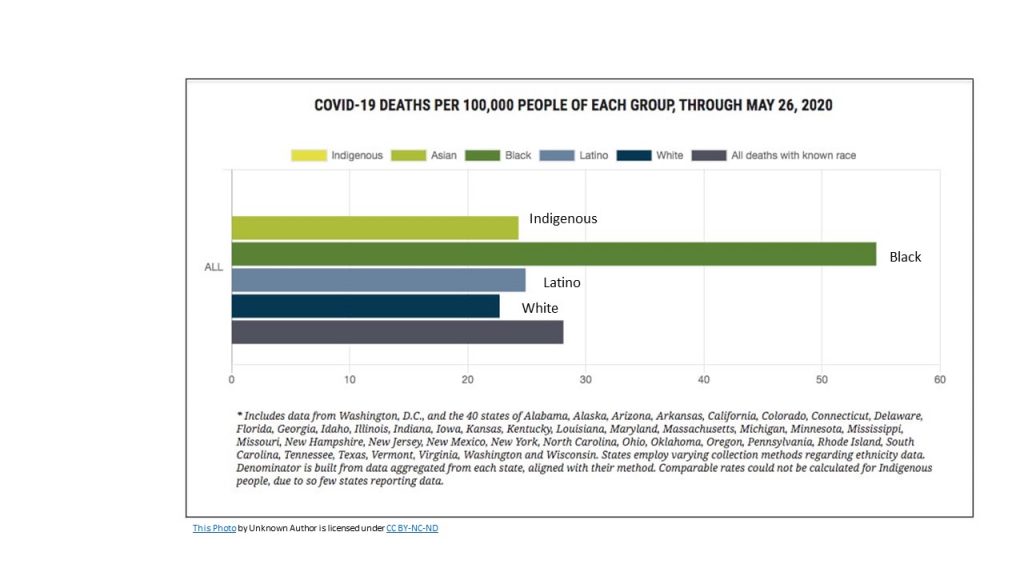

Figure 10.4 Covid-19 Deaths Per 100,000 People of Each Group, Through May 26, 2020

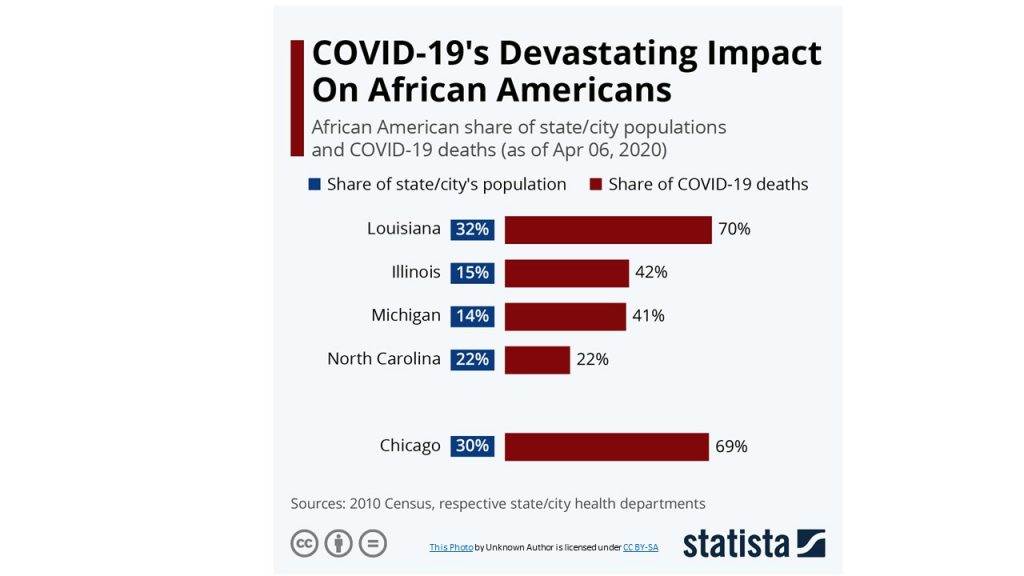

In 2020, we are currently living through a global pandemic, which has highlighted racial inequality in the United States. It became apparent that Black people were disproportionately impacted by Covid-19 early on (See Figure 10.3 Covid-19 Deaths Per 100,000 People of Each Group, Through May 26, 2020 and Figure 10.5 Covid-19’s Devastating Impact on African Americans in Select States as of April 6, 2020). According to the CDC of those who died from Covid-19 from May-August 2020, 18.7% were Black while Black people only make up 12.5% of the U.S. population and 24.2% were Hispanic while Hispanics make up only 18.5% of the U.S. population. (https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6942e1.htm)

Figure 10.5 Covid-19’s Devastating Impact on African Americans in Select States as of April 6, 2020

Why does discrimination like this occur? It is possible, of course, that some doctors are racists and decide that the lives of Black people are less valuable, but it is far more likely that they have unconscious racial biases that somehow affect their medical judgments. Regardless of the reason, the result is the same: Black people are less likely to receive potentially life-saving cardiac procedures simply because of their race. Institutional discrimination in health care, then, is literally a matter of life and death.

Housing Discrimination

When loan officers review mortgage applications, they consider many factors, including the person’s income, employment, and credit history. The law forbids them to consider race and ethnicity. Yet many studies find that Black and Latinos are more likely than whites to have their mortgage applications declined (Blank, Venkatachalam, McNeil, & Green, 2005). Because members of these groups tend to be poorer than whites and to have less desirable employment and credit histories, the higher rate of mortgage rejections may be appropriate, albeit unfortunate.

To control for this possibility, researchers take these factors into account and in effect compare whites, Black people, and Latinos with similar incomes, employment, and credit histories. Some studies are purely statistical, and some involve white, Black, and Latino individuals who independently visit the same mortgage-lending institutions and report similar employment and credit histories. Both types of studies find that Black and Latino applicants are still more likely than whites with similar qualifications to have their mortgage applications rejected (Turner et al., 2002) or to be offered mortgages carrying higher interest rates or less desirable terms.

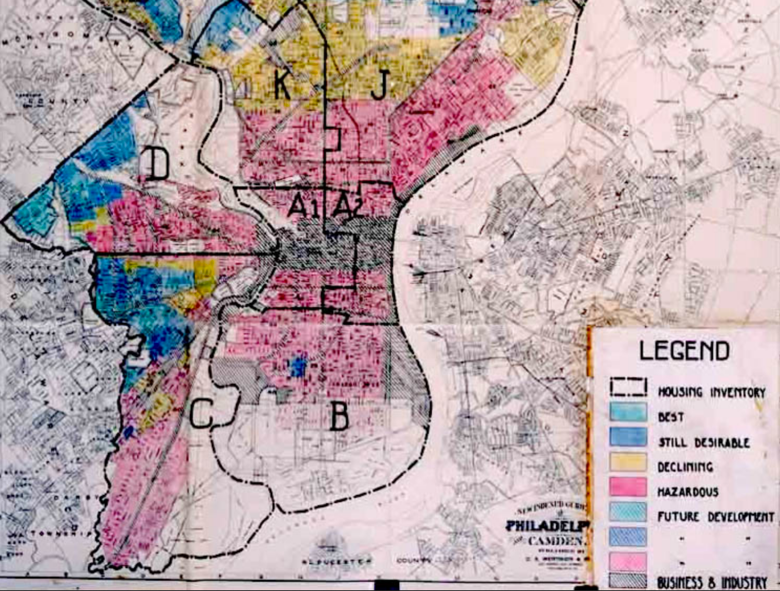

There is also evidence of banks rejecting mortgage applications for people who wish to live in certain urban, supposedly high-risk neighborhoods, and of insurance companies denying homeowner’s insurance or else charging higher rates for homes in these same neighborhoods. Practices like these that limit access to loans and insurance in certain neighborhoods are called redlining, and they also violate the law (Ezeala-Harrison, Glover, & Shaw-Jackson, 2008). Because the people affected by redlining tend to be BIPOC, redlining, too, is an example of institutional discrimination.

The denial of mortgages and homeowner’s insurance contributes to an ongoing pattern of residential segregation, which was once enforced by law but now is reinforced by a pattern of illegal institutional discrimination. Residential segregation involving Black people in northern cities intensified during the early 20th century, when tens of thousands of Black people began migrating from the South to the North to look for jobs and escape the harsh realities of living in the segregated South (Massey & Denton, 1993). Their arrival alarmed Northern whites and mob violence against Black people and bombings of their houses escalated. Fear of white violence made Black people afraid to move into white neighborhoods, and “improvement associations” in white neighborhoods sprung up in an effort to keep Black people from moving in. These associations and real estate agencies worked together to implement restrictive covenants among property owners that stipulated they would not sell or rent their properties to Black buyers. These covenants were common after 1910 and were not banned by the U.S. Supreme Court until 1948. Still, residential segregation worsened over the next few decades, as whites used various kinds of harassment, including violence, to keep Black residents out of their neighborhoods, and real estate agencies simply refused to sell property in white neighborhoods to them.

Because of continuing institutional discrimination in housing, Black people remain highly segregated by residence in many cities, much more so than is true for other people of color. Sociologists Douglas S. Massey and Nancy A. Denton (1993) term this problem hypersegregation and say it is reinforced by a pattern of subtle discrimination by realtors and homeowners that makes it difficult for Black buyers to find out about homes in white neighborhoods and to buy them. The hypersegregation that Black people experience, say Massey and Denton, cuts them off from the larger society, as many rarely leave their immediate neighborhoods, and results in “concentrated poverty,” where joblessness and other related problems are pervasive. Calling residential segregation “American apartheid,” they urge vigorous federal, state, and local action to end this ongoing problem.

Employment Discrimination

Title VII of the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned racial discrimination in employment, including hiring, wages, and firing. Table 10.2 “Median Weekly Earnings of Full-Time Workers, First Quarter, 2018” presents weekly earnings data by race and ethnicity and shows that Black and Latino workers have much lower earnings than whites and Asians. Several factors explain this disparity, including the various structural obstacles related to poverty. Despite Title VII, however, an additional reason is that Black and Latino workers continue to face discrimination in hiring and promotion (Hirsh & Cha, 2008).

Table 10.2 Median Weekly Earnings of Full-Time Workers, First Quarter, 2018

|

|

Median Weekly Earnings ($) |

% of White Earnings |

|

Black |

696 |

76.4% |

|

Asian American |

1066 |

117% |

|

Latino American |

675 |

74.1% |

|

White American |

911 |

100% |

Source: Data from U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2018). Usual Weekly Earnings of Wage and Salary Workers First Quarter 2018. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf

A now-classic field experiment documented such discrimination. Sociologist Devah Pager (2007) had young white and Black men apply independently in person for entry-level jobs. They dressed the same and reported similar levels of education and other qualifications. Some applicants also admitted having a criminal record, while other applicants reported no such record. As might be expected, applicants with a criminal record were hired at lower rates than those without a record. However, in striking evidence of racial discrimination in hiring, Black applicants without a criminal record were hired at the same low rate as the white applicants with a criminal record.

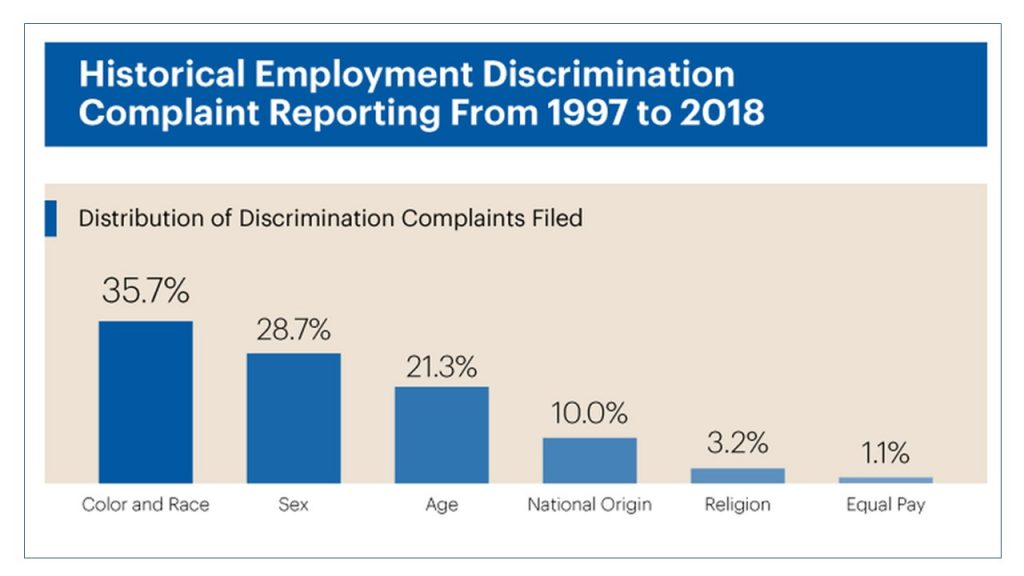

The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) is the federal agency responsible for enforcing laws that make it workplace discriminate illegal. Data from the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission shows that race is the most common factor in workplace discrimination charges (See Figure 10.5).

Figure 10.6 Historical Employment Discrimination Reporting

10.5 Patterns of Intergroup Relations

Intergroup relations (relationships between different groups of people) range along a spectrum from assimilation to pluralism. The most tolerant form of intergroup relations is pluralism, in which no distinction is made between minority and majority groups in terms of position and treatment. Groups are free to retain their unique cultural attributes and participate equally in society. Some forms of pluralism ensure by law that groups have equal access to political position, educational and economic opportunities and the like. While some forms of pluralism are equal, there are other forms that are unequal, where group separation is maintained, but minority groups are subordinated in different ways (including genocide, expulsion and segregation). At the other end of the continuum is assimilation, which is a pattern of intergroup relations in which groups become increasingly like one another. Assimilation is also defined as the process of boundary reduction between groups, and can involve the adoption of one group’s culture by another, friendship and intermarriage between members of different groups and the adoption of one group of another group’s identity. Much of the examination of intergroup relations focuses on the patterns of pluralism which favor the dominant group at the expense of a minority group. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

Genocide

Genocide, the deliberate annihilation of a targeted subordinate group, is the most toxic intergroup relationship. Historically, we can see that genocide has included both the intent to exterminate a group and the function of exterminating of a group, intentional or not.

Possibly the most well-known case of genocide is Hitler’s attempt to exterminate the Jewish people in the first part of the twentieth century. Also known as the Holocaust, the explicit goal of Hitler’s “Final Solution” was the eradication of European Jewry, as well as the destruction of other minority groups such as Catholics, people with disabilities and homosexuals. With forced emigration, concentration camps, and mass executions in gas chambers, Hitler’s Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of 12 million people, 6 million of whom were Jewish. Hitler’s intent was clear, and the high Jewish death toll certainly indicates that Hitler and his regime committed genocide. But how do we understand genocide that is not so overt and deliberate?

The treatment of aboriginal Australians is also an example of genocide committed against indigenous people. Historical accounts suggest that between 1824 and 1908, white settlers killed more than 10,000 native aborigines in Tasmania and Australia (Tatz 2006). Another example is the European colonization of North America. Some historians estimate that Native American populations dwindled from approximately 12 million people in the year 1500 to barely 237,000 by the year 1900 (Lewy 2004). European settlers coerced American Indians off their own lands, often causing thousands of deaths in forced removals, such as occurred in the Cherokee or Potawatomi Trail of Tears. Settlers also enslaved Native Americans and forced them to give up their religious and cultural practices. But the major cause of Native American death was neither slavery nor war nor forced removal: it was the introduction of European diseases and Indians’ lack of immunity to them. Smallpox, diphtheria, and measles flourished among indigenous American tribes who had no exposure to the diseases and no ability to fight them. Quite simply, these diseases decimated the tribes. How planned this genocide was remains a topic of contention. Some argue that the spread of disease was an unintended effect of conquest, while others believe it was intentional citing rumors of smallpox-infected blankets being distributed as “gifts” to tribes.

Genocide is not a just a historical concept; it is practiced today. Recently, ethnic and geographic conflicts in the Darfur region of Sudan have led to hundreds of thousands of deaths. As part of an ongoing land conflict, the Sudanese government and their state-sponsored Janjaweed militia have led a campaign of killing, forced displacement, and systematic rape of Darfuri people. Although a treaty was signed in 2011, the peace is fragile. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

Expulsion

Expulsion refers to a subordinate group being forced, by a dominant group, to leave a certain area or country. As seen in the examples of the Trail of Tears and the Holocaust, expulsion can be a factor in genocide. However, it can also stand on its own as a destructive group interaction. Expulsion has often occurred historically with an ethnic or racial basis. In the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in 1942, after the Japanese government’s attack on Pearl Harbor. The Order authorized the establishment of internment camps for anyone with as little as one-eighth Japanese ancestry (i.e., one great-grandparent who was Japanese). Over 120,000 legal Japanese residents and Japanese U.S. citizens, many of them children, were held in these camps for up to four years, despite the fact that there was never any evidence of collusion or espionage. (In fact, many Japanese Americans continued to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States by serving in the U.S. military during the War.) In the 1990s, the U.S. executive branch issued a formal apology for this expulsion; reparation efforts continue today. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

Segregation

Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace, schools and social functions. It is important to distinguish between de jure segregation (segregation that is enforced by law) and de facto segregation (segregation that occurs without laws but by custom). A stark example of de jure segregation is the apartheid movement of South Africa, which existed from 1948 to 1994. Under apartheid, black South Africans were stripped of their civil rights and forcibly relocated to areas that segregated them physically from their white compatriots. Only after decades of degradation, violent uprisings, and international advocacy was apartheid finally abolished.

De jure segregation occurred in the United States for many years after the Civil War. During this time, many former Confederate states passed Jim Crow laws that required segregated facilities for blacks and whites. These laws were codified in 1896’s landmark Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson, which stated that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional. For the next five decades, Black people were subjected to legalized discrimination, forced to live, work, and go to school in separate—but unequal—facilities. It wasn’t until 1954 and the Brown v. Board of Education case that the Supreme Court declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” thus ending de jure segregation in the United States.

De facto segregation, however, cannot be abolished by any court mandate. Segregation is still alive and well in the United States, with different racial or ethnic groups often segregated by neighborhood. Sociologists use segregation indices to measure racial segregation of different races in different areas. The indices employ a scale from zero to 100, where zero is the most integrated and 100 is the least. In the New York metropolitan area, for instance, the black-white segregation index was seventy-nine for the years 2005–2009. This means that 79 percent of either blacks or whites would have to move in order for each neighborhood to have the same racial balance as the whole metro region (Population Studies Center 2010). (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/ 02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

10.6 Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States

One of the best ways to begin to understand racial and ethnic inequality in the United States is to read firsthand accounts by such great writers as Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Piri Thomas, Richard Wright, and Malcolm X, all of whom wrote moving, autobiographical accounts of the bigotry and discrimination they faced in their lives.

Statistics also give a picture of racial and ethnic inequality in the United States. We can begin to get a picture of this inequality by examining racial and ethnic differences in such life chances as income, education, and health. Table 10.3 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” presents data on some of these differences.

Table 10.3 Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States

|

|

White American |

Black American |

Latino American |

Asian American |

Native American |

|

Median Family Income, 2016 |

65,041 |

39,490 |

47,675 |

81,431 |

39,719 |

|

% earning a bachelor’s degree or more, 2015 |

36.2 |

22.5 |

15.5 |

53.9 |

13 (2010) |

|

% in poverty, 2016 |

8.8 |

22.0 |

19.4 |

10.1 |

26.2 |

|

Infant Mortality Rate, 2014 |

4.89 |

10.93 |

5.01 |

3.86 |

7.59 |

Source: Data from Semega, Jessica L., Kayla R. Fontenot, and Melissa A. Kollar, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-259, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2016, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/demo/P60-259.pdf;

Ryan, Camille L and Kurt Bauman, U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P20-578, Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf; and

Recent trends in infant mortality in the United States. NCHS Data Brief, Number 279 (March 2017r). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db279.htm.

The data are clear: U.S. racial and ethnic groups differ dramatically in their life chances. Compared to whites, for example, Black, Latino, and Native Americans have much lower family incomes and much higher rates of poverty; they are also much less likely to have college degrees. In addition, Black and Native Americans have much higher infant mortality rates than whites: black infants, for example, are more than twice as likely as white infants to die. These comparisons obscure some differences within some of the groups just mentioned. Among Latinos, for example, Cuban Americans have fared better than Latinos overall, and Puerto Ricans worse. Similarly, among Asians, people with Chinese and Japanese backgrounds have fared better than those from Cambodia, Korea, and Vietnam.

Although Table 10.3 “Selected Indicators of Racial and Ethnic Inequality in the United States” shows that African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans fare much worse than whites, it presents a more complex pattern for Asian Americans. Compared to whites, Asian Americans have higher family incomes and are more likely to hold college degrees, but they also have a higher poverty rate. Thus, many Asian Americans do relatively well, while others fare relatively worse, as just noted. Although Asian Americans are often viewed as a “model minority,” meaning that they have achieved educational and economic success despite not being white, some Asians have been less able than others to climb the economic ladder. Moreover, stereotypes of Asian Americans and discrimination against them remain serious problems (Chou & Feagin, 2008; Fong, 2007). Even the overall success rate of Asian Americans obscures the fact that their occupations and incomes are often lower than would be expected from their educational attainment and they have to work harder for their success (Hurh & Kim, 1999).

Explaining Racial and Ethnic Inequality

Why do racial and ethnic inequality exist? Why do Black, Latino, Native American, and some Asian Americans fare worse than whites? In answering these questions, many people have some very strong opinions.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, longstanding explanations have focused on the dominant groups beliefs in biological or cultural inferiority of minority groups. The idea that minorities are naturally less intelligent or otherwise biologically inferior, or that cultural deficiencies, including a failure to value hard work, have served to account for social inequalities. As discussed, Geneticists have found no evidence for the biological view of race and many social scientists find little or no evidence of cultural problems in minority communities and say that the belief in cultural deficiencies is an example of cultural racism that blames the victim. Social scientists, such as Elijah Anderson (1999) have found that where problematic behavior or attitudes exist, they arise as a result of segregation, extreme poverty and other challenges these citizens face in their daily lives. Thus, cultural problems arise out of structural problems, rather than the reverse. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

A third explanation for U.S. racial and ethnic inequality is based in the conflict perspective. This view attributes racial and ethnic inequality to institutional and individual discrimination and a lack of opportunity in education and other spheres of life (Feagin, 2006). Segregated housing, for example, prevents Black people from escaping the inner city and from moving to areas with greater employment opportunities. Employment discrimination keeps the salaries of BIPOC much lower than they would be otherwise. The schools that many children of color attend every day are typically overcrowded and underfunded. As these problems continue from one generation to the next, it becomes very difficult for people already at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder to climb up it because of their race and ethnicity.

10.7 Race and Ethnicity in the 21st Century

At the beginning of this chapter we noted that the more things change, the more they stay the same. We saw evidence of this in proclamations over the years about the status of BIPOC in the United States. As a reminder, in 1903 sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois wrote in his classic book The Souls of Black Folk that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” Some six decades later, social scientists and government commissions during the 1960s continued to warn us about the race problem in the United States and placed the blame for this problem squarely in the hands of whites and of the social and economic institutions that discriminate against BIPOC (Kerner Commission, 1968). Three to four decades after these warnings, social scientists during the 1990s and 2000s wrote that conditions had actually worsened for BIPOC since the 1960s (Massey & Denton, 1993; Wilson, 1996; Hacker, 2003).

Now that we have examined race and ethnicity in the United States, what have we found? Where do we stand almost two decades into the new century and just more than 100 years after Du Bois wrote about the problem of the color line? Did the historic elections of Barack Obama as president in 2008 and 2012 signify a new era of equality between the races, as many observers wrote, or did his election occur despite the continued existence of pervasive racial and ethnic inequality?

On the one hand, there is cause for hope. Legal segregation is gone. The vicious, overt racism that was so rampant in this country into the 1960s has declined since that tumultuous time. BIPOC have made important gains in several spheres of life, and occupy some important elected positions in and outside the South, a feat that would have been unimaginable a generation ago.

On the other hand, there is also cause for despair. Overt racism has been replaced by a modern, cultural racism that still blames BIPOC for their problems and reduces public support for government policies to deal with their problems. Institutional discrimination remains pervasive, and hate crimes remain all too common. Americans of different racial and ethnic backgrounds remain sharply divided on many issues, reminding us that the United States as a nation remains divided by race and ethnicity. Two issues that continue to arouse controversy are affirmative action and immigration, to which we now turn.

Affirmative Action

Affirmative action refers to the policies and practices offering equal opportunity to minorities and women in employment and education. Affirmative action programs were begun in the 1960s to provide groups who experienced historic discrimination equal access to jobs and education. President John F. Kennedy was the first known official to use the term, when he signed an executive order in 1961 ordering federal contractors to “take affirmative action” in ensuring that applicants are hired and treated without regard to their race and national origin. Six years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson added sex to race and national origin as demographic categories for which affirmative action should be used.

Although many affirmative action programs remain in effect today, court rulings, state legislation, and other efforts have limited their number and scope. Despite this curtailment, affirmative action continues to spark much controversy, with scholars, members of the public, and elected officials all holding strong views on the issue (Karr, 2008; Wise, 2005; Cohen & Sterba, 2003).

One of the major court rulings associated with affirmative action was the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). Allan Bakke was a 35-year-old white man who had twice been rejected for admission into the medical school at the University of California, Davis. At the time he applied, UC–Davis had a policy of reserving 16 seats in its entering class of 100 for qualified BIPOC to make up for their underrepresentation in the medical profession. Bakke’s college grades and scores on the Medical College Admission Test were higher than those of the BIPOC admitted to UC–Davis either time Bakke applied. He sued for admission on the grounds that his rejection amounted to reverse racial discrimination on the basis of his being white (Stefoff, 2005).

The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which ruled 5–4 that Bakke must be admitted into the UC–Davis medical school because he had been unfairly denied admission on the basis of his race. As part of its historic but complex decision, the Court thus rejected the use of strict racial quotas in admission as it declared that no applicant could be excluded based solely on the applicant’s race. At the same time, however, the Court also declared that race may be used as one of the several criteria that admissions committees consider when making their decisions. For example, if an institution desires racial diversity among its students, it may use race as an admissions criterion along with other factors such as grades and test scores.

Two more recent Supreme Court cases both involved the University of Michigan: Gratz v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 244 (2003), which involved the university’s undergraduate admissions, and Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306 (2003), which involved the university’s law school admissions. In Grutter the Court reaffirmed the right of institutions of higher education to take race into account in the admissions process. In Gratz, however, the Court invalidated the university’s policy of awarding additional points to high school students of color as part of its use of a point system to evaluate applicants; the Court said that consideration of applicants needed to be more individualized than a point system allowed.

Drawing on these Supreme Court rulings, then, affirmative action in higher education admissions on the basis of race and ethnicity is permissible as long as it does not involve a rigid quota system and as long as it does involve an individualized way of evaluating candidates. Race may be used as one of several criteria in such an individualized evaluation process, but it must not be used as the only criterion.

The Debate over Affirmative Action

Opponents of affirmative action cite several reasons for opposing it. Affirmative action, they say, results in reverse discrimination. They argue people benefiting from affirmative action are less qualified than many of the white males with whom they compete for employment and college admissions. In addition, opponents say, affirmative action implies that the people benefiting from it need extra help and thus are indeed less qualified which stigmatizes the groups benefiting from these policies and programs.

In response proponents of affirmative action give several reasons for favoring it. Many say it is needed to make up not just for past discrimination and a lack of opportunities for people of color but also for ongoing discrimination and a lack of opportunity. For example, because of their social networks, whites are much better able than BIPOC to find out about and to get jobs (Reskin, 1998). If this is true, BIPOC are automatically at a disadvantage in the job market, and some form of affirmative action is needed to give them an equal chance at employment. Proponents also say that affirmative action helps add diversity to the workplace and to the campus. Many colleges, they note, give some preference to high school students who live in a distant state or rural communities in order to add needed diversity to the student body; to “legacy” students—those with a parent who went to the same institution—to reinforce alumni loyalty and to motivate alumni to donate to the institution; and to athletes, musicians, and other applicants with certain specialized talents and skills. If all of these forms of preferential admission make sense, proponents say, it also makes sense to take students’ racial and ethnic backgrounds into account as admissions officers strive to have a diverse student body.

Proponents add that affirmative action has indeed succeeded in expanding employment and educational opportunities for women and BIPOC with women being the biggest beneficiaries of affirmative action, and that individuals benefiting from affirmative action have fared well in the workplace or on the campus. In this regard research finds that Black students graduating from selective U.S. colleges and universities after being admitted under affirmative action guidelines are slightly more likely than their white counterparts to obtain professional degrees and to become involved in civic affairs (Bowen & Bok, 1998). Furthermore, white men have benefited from affirmative action policies as jobs that would have been passed on to friends and family of employers now require open job calls brining in more qualified applicants. Unfortunately, BIPOC applicants are often overlooked for jobs that are given to less qualified white applicants (Desmond & Emirbayer, 2020).