12

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Define power the three types of authority and discuss the fundamental differences between “elite” and “pluralist” theories of power.

- Explain political ideology, how it’s measured, and what roles it plays in politics and political participation.

- Define war and terrorism and outline the differences between the them.

- Outline the major components of the current economy and outline the economic development of societies.

- Define capitalism and socialism and discuss the advantages and shortcomings of both.

- Understand the globalization of the economy and its effects on societies.

12.1 Power and Authority

Politics refers to the distribution and exercise of power within a society, and polity refers to the political institution through which power is distributed and exercised. In any society, decisions must be made regarding the allocation of resources and other matters. Except perhaps in the simplest societies, specific people and often specific organizations make these decisions. Depending on the society, they sometimes make these decisions solely to benefit themselves and other times make these decisions to benefit the society as a whole. Regardless of who benefits, a central point is this: some individuals and groups have more power than others. Because power is so essential to an understanding of politics, we begin our discussion of politics with a discussion of power.

Power refers to the ability to have one’s will carried out despite the resistance of others. Most of us have seen a striking example of raw power when we are driving a car and see a police car in our rearview mirror. At that particular moment, the driver of that car has enormous power over us. We make sure we strictly obey the speed limit and all other driving rules. If, alas, the police car’s lights are flashing, we stop the car, as otherwise we may be in for even bigger trouble. When the officer approaches our car, we ordinarily try to be as polite as possible and pray we do not get a ticket. When you were 16 and your parents told you to be home by midnight or else, your arrival home by this curfew again illustrated the use of power, in this case parental power. If a child in middle school gives her lunch to a bully who threatens her, that again is an example of the use of power, or, in this case, the misuse of power.

These are all vivid examples of power, but the power that social scientists study is both grander and, often, more invisible (Wrong, 1996). Much of it occurs behind the scenes, and scholars continue to debate who is wielding it and for whose benefit they wield it. Many years ago, Max Weber (1921/1978), one of the founders of sociology discussed in earlier chapters, distinguished authority as a special type of power. Authority (or legitimate authority), Weber said, is power whose use is considered just and appropriate by those over whom the power is exercised. The example of the police car in our rearview mirrors is an example of authority. Conversely, coercion is a form of power that is exercised over an individual, but is not considered to be legitimate. The bully who threatens their classmates into giving up their lunch has used coercion.

Weber’s keen insight lay in distinguishing different types of legitimate authority that characterize different types of societies, especially as they evolve from simple to more complex societies. He called these three types traditional authority, rational-legal authority, and charismatic authority. We turn to these now.

Traditional Authority

As the name implies, traditional authority is power that is rooted in traditional, or long-standing, beliefs and practices of a society. It exists and is assigned to particular individuals because of that society’s customs and traditions. Individuals enjoy traditional authority for at least one of two reasons. The first is inheritance, as certain individuals are granted traditional authority because they are the children or other relatives of people who already exercise traditional authority. The second reason individuals enjoy traditional authority is more religious: their societies believe they are anointed by God or the gods, depending on the society’s religious beliefs, to lead their society. Traditional authority is common in many preindustrial societies, where tradition and custom are so important, but also in more modern monarchies, where a king, queen, or prince enjoys power because she or he comes from a royal family. In addition, traditional authority relates to the power that parents have over children and that men have over women in patriarchal societies.

Traditional authority is granted to individuals regardless of their qualifications. They do not have to possess any special skills to receive and wield their authority, as their claim to it is based solely on their bloodline or supposed divine designation. An individual granted traditional authority can be intelligent or stupid, fair or arbitrary, and exciting or boring but receives the authority just the same because of custom and tradition. As not all individuals granted traditional authority are particularly well qualified to use it, societies governed by traditional authority sometimes find that individuals bestowed it are not always up to the job.

Rational-Legal Authority

If traditional authority derives from custom and tradition, rational-legal authority derives from law and is based on a belief in the legitimacy of a society’s laws and rules and in the right of leaders to act under these rules to make decisions and set policy. This form of authority is a hallmark of modern democracies, where power is given to people elected by voters, and the rules for wielding that power are usually set forth in a constitution, a charter, or another written document. Whereas traditional authority resides in an individual because of inheritance or divine designation, rational-legal authority resides in the office filled by an individual, not in the individual per se. The authority of the president of the United States thus resides in the office of the presidency, not in the individual who happens to be president. When that individual leaves office, authority transfers to the next president. This transfer is usually smooth and stable, and one of the marvels of democracy is that officeholders are replaced in elections without revolutions having to be necessary. We might not have voted for the person who wins the presidency, but we accept that person’s authority as our president when he (so far it has always been a “he”) assumes office.

Rational-legal authority helps ensure an orderly transfer of power in a time of crisis. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Vice President Lyndon Johnson was immediately sworn in as the next president. When Richard Nixon resigned his office in disgrace in 1974 because of his involvement in the Watergate scandal, Vice President Gerald Ford (who himself had become vice president after Spiro Agnew resigned because of financial corruption) became president. Because the U.S. Constitution provided for the transfer of power when the presidency was vacant, and because U.S. leaders and members of the public accept the authority of the Constitution on these and so many other matters, the transfer of power in 1963 and 1974 was smooth and orderly.

Charismatic Authority

Charismatic authority stems from an individual’s extraordinary personal qualities and from that individual’s hold over followers because of these qualities. Such charismatic individuals may exercise authority over a whole society or only a specific group within a larger society. They can exercise authority for good and for bad, as this brief list of charismatic leaders indicates: Joan of Arc, Adolf Hitler, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus Christ, Muhammad, and Buddha. Each of these individuals had extraordinary personal qualities that led their followers to admire them and to follow their orders or requests for action.

Charismatic authority can reside in a person who came to a position of leadership because of traditional or rational-legal authority. Over the centuries, several kings and queens of England and other European nations were charismatic individuals as well (while some were far from charismatic). A few U.S. presidents—Washington, Lincoln, both Roosevelts, Kennedy, Reagan, and Clinton—also were charismatic, and much of their popularity stemmed from various personal qualities that attracted the public and sometimes even the press. Ronald Reagan, for example, was often called “the Teflon president,” because he was so loved by much of the public that accusations of ineptitude or malfeasance did not stick to him (Lanoue, 1988).

Weber emphasized that charismatic authority in its pure form (i.e., when authority resides in someone solely because of the person’s charisma and not because the person also has traditional or rational-legal authority) is less stable than traditional authority or rational-legal authority. The reason for this is simple: when charismatic leaders die, their authority dies as well. Although a charismatic leader’s example may continue to inspire people long after the leader dies, it is difficult for another leader to come along and command people’s devotion as intensely. After the deaths of all the charismatic leaders named in the preceding paragraph, no one came close to replacing them in the hearts and minds of their followers.

Because charismatic leaders recognize that their eventual death may well undermine the nation or cause they represent, they often designate a replacement leader, who they hope will also have charismatic qualities. This new leader may be a grown child of the charismatic leader or someone else the leader knows and trusts. The danger, of course, is that any new leaders will lack sufficient charisma to have their authority accepted by the followers of the original charismatic leader. For this reason, Weber recognized that charismatic authority ultimately becomes more stable when it is evolves into traditional or rational-legal authority. Transformation into traditional authority can happen when charismatic leaders’ authority becomes accepted as residing in their bloodlines, so that their authority passes to their children and then to their grandchildren. Transformation into rational-legal authority occurs when a society ruled by a charismatic leader develops the rules and bureaucratic structures that we associate with a government. Weber used the term routinization of charisma to refer to the transformation of charismatic authority in either of these ways.

12.2 Types of Political Systems

Various states and governments obviously exist around the world. In this context, state means the political unit within which power and authority reside. This unit can be a whole nation or a subdivision within a nation. Thus, the nations of the world are sometimes referred to as states (or nation-states), as are subdivisions within a nation, such as California, New York, and Texas in the United States. Government means the group of persons who direct the political affairs of a state, but it can also mean the type of rule by which a state is run. Another term for this second meaning of government is political system, which we will use here along with government. The type of government under which people live has fundamental implications for their freedom, their welfare, and even their lives. There are different ways to categorize the forms of government. In sociology, governments are typically categorized based upon the source of power. As such, there are three broad types of political systems, including democracies, oligarchies and autocracies. Democracy, as discussed below, means “rule by the people,” oligarchy means “rule of the few,” while autocracies are systems of government in which power is held by one person, whose decisions are not subject to oversight. Below, we briefly review the major political systems in the world today.

Democracy

The type of government with which we are most familiar is democracy, or a political system in which citizens govern themselves either directly or indirectly. The term democracy comes from Greek and means “rule of the people.” In Lincoln’s stirring words from the Gettysburg Address, democracy is “government of the people, by the people, for the people.” In direct democracies, people make their own decisions about the policies and distribution of resources that affect them directly. An example of such a democracy in action is the New England town meeting, where the residents of a town meet once a year and vote on budgetary and other matters. However, such direct democracies are impractical when the number of people gets beyond a few hundred. Representative democracies are thus much more common. In these types of democracies, people elect officials to represent them in legislative votes on matters affecting the population.

Representative democracy is more practical than direct democracy in a society of any significant size, but political scientists cite another advantage of representative democracy. At least in theory, it ensures that the individuals who govern a society and in other ways help a society function are the individuals who have the appropriate talents, skills, and knowledge to do so. In this way of thinking, the masses of people are, overall, too uninformed, too uneducated, and too uninterested to run a society themselves. Representative democracy thus allows for “the cream to rise to the top” so that the people who actually govern a society are the most qualified to perform this essential task (Seward, 2010). Although this argument has much merit, it is also true that many of the individuals who do get elected to office come from the upper class, and turn out to be ineffective and/or corrupt. Regardless of our political orientations, Americans can think of many politicians to whom these labels apply, from presidents down to local officials. Elected officials may also be unduly influenced by campaign contributions from corporations and other special-interest groups. To the extent this influence occurs, representative democracy falls short of the ideals proclaimed by political theorists.

The defining feature of representative democracy is voting in elections. When the United States was established more than 240 years ago, most of the world’s governments were monarchies or other authoritarian regimes (discussed shortly). Like the colonists, people in these nations chafed under arbitrary power. The example of the American Revolution and the stirring words of its Declaration of Independence helped inspire the French Revolution of 1789 and other revolutions since, as people around the world have died in order to win the right to vote and to have political freedom.

Democracies are certainly not perfect. Their decision-making process can be quite slow and inefficient; as just mentioned, decisions may be made for special interests and not “for the people”; and, as we have seen in earlier chapters, pervasive inequalities of social class, race and ethnicity, gender, and age can exist. Moreover, in not all democracies have all people enjoyed the right to vote. In the United States, for example, Black citizens could not vote until after the Civil War, with the passage of the 15th Amendment in 1870, and women did not win the right to vote until 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

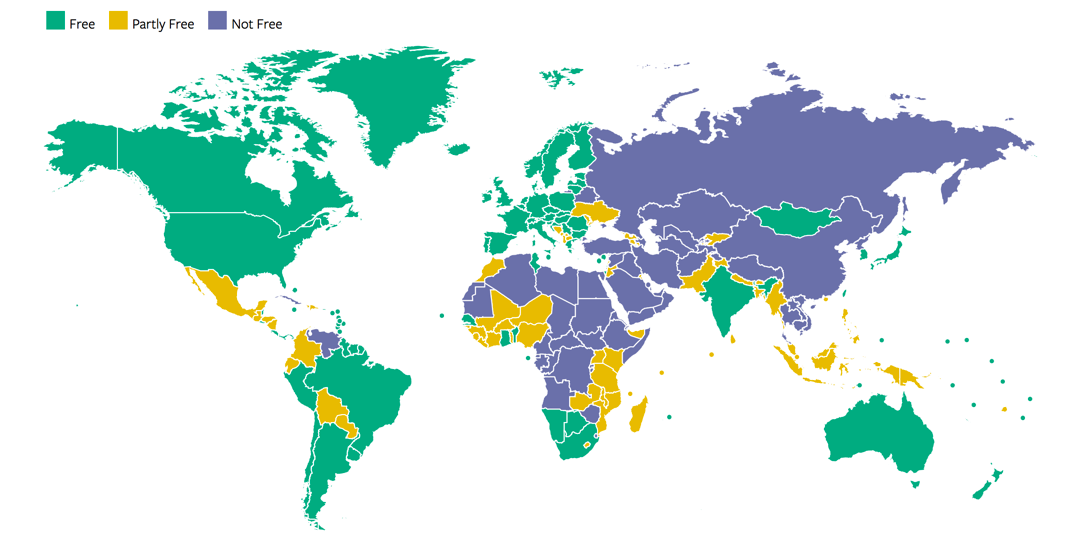

In addition to generally enjoying the right to vote, people in democracies also have more freedom than those in other types of governments. Figure 12.1 “Freedom Around the World (Based on Extent of Political Rights and Civil Liberties)” depicts the nations of the world according to the extent of their political rights and civil liberties. The freest nations are found in North America, Western Europe, and certain other parts of the world, while the least free lie in Asia, the Middle East, and Africa.

Figure 12.1 Freedom Around the World (Based on Extent of Political Rights and Civil Liberties)

Monarchy

A Monarchy is a political system in which power resides in a single family that rules from one generation to the next generation. The power the family enjoys is traditional authority, and many monarchs command respect because their subjects bestow this type of authority on them. Other monarchs, however, have ensured respect through arbitrary power and even terror. Royal families still rule today, but their power has declined from centuries ago. Today the Queen of England holds a largely ceremonial position, but her predecessors on the throne wielded much more power.

This example reflects a historical change in types of monarchies from absolute monarchies to constitutional monarchies (Finer, 1997). In absolute monarchies, the royal family claims a divine right to rule and exercises considerable power over their kingdom. Absolute monarchies were common in both ancient (e.g., Egypt) and medieval (e.g., England and China) times. In reality, the power of many absolute monarchs was not totally absolute, as kings and queens had to keep in mind the needs and desires of other powerful parties, including the clergy and nobility. Over time, absolute monarchies gave way to constitutional monarchies. In these monarchies, the royal family serves a symbolic and ceremonial role and enjoys little, if any, real power. Instead the executive and legislative branches of government—the prime minister and parliament in several nations—run the government, even if the royal family continues to command admiration and respect. Constitutional monarchies exist today in several nations, including Denmark, Great Britain, Norway, Spain, and Sweden.

Authoritarianism and Totalitarianism

Authoritarianism and totalitarianism are general terms for nondemocratic political systems ruled by an individual or a group of individuals who are not freely elected by their populations and who often exercise arbitrary power. To be more specific, authoritarianism refers to political systems in which an individual or a group of individuals holds power, restricts or prohibits popular participation in governance, and represses dissent. Totalitarianism refers to political systems that include all the features of authoritarianism but are even more repressive as they try to regulate and control all aspects of citizens’ lives and fortunes. People can be imprisoned for deviating from acceptable practices or may even be killed if they dissent in the mildest of ways. The purple nations in Figure 11.1 “Freedom Around the World (Based on Extent of Political Rights and Civil Liberties)” are mostly totalitarian regimes, and the yellow ones are authoritarian.

Compared to democracies and monarchies, authoritarian and totalitarian governments are more unstable politically. The major reason for this is that these governments enjoy no legitimate authority. Instead their power rests on fear and repression. The populations of these governments do not willingly lend their obedience to their leaders and realize that their leaders are treating them very poorly; for both these reasons, they are more likely than populations in democratic states to want to rebel. Sometimes they do rebel, and if the rebellion becomes sufficiently massive and widespread, a revolution occurs. In contrast, populations in democratic states usually perceive that they are treated more or less fairly and, further, that they can change things they do not like through the electoral process. Seeing no need for revolution, they do not revolt.

Since World War II, which helped make the United States an international power, the United States has opposed some authoritarian and totalitarian regimes while supporting others. The Cold War pitted the United States and its allies against Communist nations, primarily the Soviet Union, China, Cuba, and North Korea. But at the same time the United States opposed these authoritarian governments, it supported many others, including those in Chile, Guatemala, and South Vietnam, that repressed and even murdered their own citizens who dared to engage in the kind of dissent constitutionally protected in the United States (Sullivan, 2008). Earlier in U.S. history, the federal and state governments repressed dissent by passing legislation that prohibited criticism of World War I and then by imprisoning citizens who criticized that war (Goldstein, 2001). During the 1960s and 1970s, the FBI, the CIA, and other federal agencies spied on tens of thousands of citizens who engaged in dissent protected by the First Amendment (Cunningham, 2004). While the United States remains a beacon of freedom and hope to much of the world’s peoples, its own support for repression in the recent and more distant past suggests that eternal vigilance is needed to ensure that “liberty and justice for all” is not just an empty slogan.

12.3 Theories of Power and Society

These remarks raise some important questions: Just how democratic is the United States? Whose interests do our elected representatives serve? Is political power concentrated in the hands of a few or widely dispersed among all segments of the population? These and other related questions lie at the heart of theories of power and society. Let’s take a brief look at some of these theories.

Pluralist Theory: A functionalist Perspective

The smooth running of society is a central concern of functionalist theory. When applied to the issue of political power, functionalist theory takes the form of pluralist theory, which says that political power in the United States and other democracies is dispersed among several “veto groups” that compete in the political process for resources and influence. Sometimes one particular veto group may win and other times another group may win, but in the long run they win and lose equally and no one group has any more influence than another (Dahl, 1956).

As this process unfolds, says pluralist theory, the government might be an active participant, but it is an impartial participant. Just as parents act as impartial arbiters when their children argue with each other, so does the government act as a neutral referee to ensure that the competition among veto groups is done fairly, that no group acquires undue influence, and that the needs and interests of the citizenry are kept in mind.

The process of veto-group competition and its supervision by the government is functional for society, according to pluralist theory, for three reasons. First, it ensures that conflict among the groups is channeled within the political process instead of turning into outright hostility. Second, the competition among the veto groups means that all of these groups achieve their goals to at least some degree. Third, the government’s supervision helps ensure that the outcome of the group competition benefits society as a whole.

Elite Theories: Conflict Perspectives

Several elite theories dispute the pluralist model. According to these theories, power in democratic societies is concentrated in the hands of a few wealthy individuals and organizations—or economic elites—that exert inordinate influence on the government and can shape its decisions to benefit their own interests. Far from being a neutral referee over competition among veto groups, the government is said to be controlled by economic elites or at least to cater to their needs and interests. As should by now be clear, elite theories fall squarely within the conflict perspective.

Perhaps the most famous elite theory is the power-elite theory of C. Wright Mills (1956). According to Mills, the power elite is composed of government, big business, and the military, which together constitute a ruling class that controls society and works for its own interests, not for the interests of the citizenry. Members of the power elite, Mills said, see each other socially and serve together on the boards of directors of corporations, charitable organizations, and other bodies. When cabinet members, senators, and top generals and other military officials retire, they often become corporate executives. Conversely, corporate executives often become cabinet members and other key political appointees. This circulation of the elites helps ensure their dominance over American life.

Mills’ power-elite model remains popular, but other elite theories exist. They differ from Mills’ model in several ways, including their view of the composition of the ruling class. Several theories see the ruling class as composed mostly of the large corporations and wealthiest individuals and see government and the military serving the needs of the ruling class rather than being part of it, as Mills implied. G. William Domhoff (2010) says that the ruling class is composed of the richest 0.5% to 1% of the population, who control more than half the nation’s wealth, sit on the boards of directors just mentioned, and are members of the same social clubs and other voluntary organizations. Their control of corporations and other economic and political bodies helps maintain their inordinate influence over American life and politics.

Other elite theories say the government is more autonomous—not as controlled by the ruling class—than Mills thought. Sometimes the government takes the side of the ruling class and corporate interests, but sometimes it opposes them. Such relative autonomy, these theories say, helps ensure the legitimacy of the state, because if it always took the side of the rich it would look too biased and lose the support of the populace. In the long run, then, the relative autonomy of the state helps maintain ruling class control by making the masses feel the state is impartial when in fact it is not (Thompson, 1975).

Assessing Pluralist and Elite Theories

As a way of understanding power in the United States and other democracies, pluralist and elite theories have much to offer, but neither type of theory presents a complete picture. Pluralist theory errs in seeing all special-interest groups as equally powerful and influential. Certainly, the success of lobbying groups such as the National Rifle Association and the American Medical Association in the political and economic systems is testimony to the fact that not all special-interest groups are created equal. Pluralist theory also errs in seeing the government as a neutral referee. Sometimes the government does take sides on behalf of corporations by acting, or failing to act, in a certain way.

For example, U.S. antipollution laws and regulations are notoriously weak because of the influence of major corporations on the political process. Through their campaign contributions, lobbying, and other types of influence, corporations help ensure that pollution controls are kept as weak as possible (Simon, 2008). This problem received worldwide attention in the spring of 2010 after the explosion of an oil rig owned by BP, a major oil and energy company, spilled tens of thousands of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico in the biggest environmental disaster in U.S. history. As the oil was leaking, news reports emphasized that individuals or political action committees (PACs) associated with BP had contributed $500,000 to U.S. candidates in the 2008 elections, that BP had spent $16 million on lobbying in 2009, and that the oil and gas industry had spent tens of millions of dollars on lobbying that year (Montopoli, 2010).

Although these examples support the views of elite theories, the theories also paint too simple a picture. They err in implying that the ruling class acts as a unified force in protecting its interests. Corporations sometimes do oppose each other for profits and sometimes even steal secrets from each other, and governments do not always support the ruling class. For example, the U.S. government has tried to reduce tobacco smoking despite the wealth and influence of tobacco companies. While the United States, then, does not entirely fit the pluralist vision of power and society, neither does it entirely fit the elite vision. Yet the evidence that does exist of elite influence on the American political and economic systems reminds us that government is not always “of the people, by the people, for the people,” however much we may wish it otherwise.

12.4 Politics in the United States

The discussion of theories of power and society began to examine the U.S. political system. Let’s continue this examination by looking at additional features of U.S. politics. Two central components of modern political systems are (a) the views that people hold of social, economic, and political issues and (b) the political organizations that try to elect candidates to represent those views. We call these components political ideology and political parties, respectively.

Political Ideology

Political ideology is a complex concept that is often summarized by asking people whether they are liberal or conservative. In 2016, the General Social Survey questioned respondents about their political ideology, and responses to this question are grouped into three categories—liberal, moderate, and conservative—and displayed in Figure 12.2 “Political Ideology”. We see that moderates slightly outnumber conservatives, who in turn outnumber liberals.

Figure 12.2 Political Ideology

This is a common measure of political ideology, but social scientists often advise using a series of questions to measure political ideology, which consists of views on at least two sorts of issues, social and economic. Social issues concern attitudes on such things as abortion and other controversial behaviors and government spending on various social problems. Economic issues, on the other hand, concern such things as taxes and the distribution of income and wealth. People can hold either liberal or conservative attitudes on both types of issues, but they can also hold mixed attitudes: liberal on social issues and conservative on economic ones, or conservative on social issues and liberal on economic ones. Educated, wealthy people, for example, may want lower taxes (generally considered a conservative view) but also may favor abortion rights and oppose the death penalty (both considered liberal positions). In contrast, less educated, working-class people may favor higher taxes for the rich (a liberal view, perhaps) but oppose abortion rights and favor the death penalty.

Political Parties

People’s political ideologies often lead them to align with a political party, or an organization that supports particular political positions and tries to elect candidates to office to represent those positions. The two major political parties in the United States are, of course, the Democratic and Republican parties. However, in the 2017 Gallup poll, 42% of Americans identify as Independents, compared to 29% who identify themselves as Democrats and 27% who identify themselves as Republicans. The number of Americans who consider themselves Independents, then, almost equals the number who consider themselves either Democrats or Republicans (Jones, 2018).

An important question for U.S. democracy is how much the Democratic and Republican parties differ on the major issues of the day. The Democratic Party is generally regarded as more liberal, while the Republican Party is regarded as more conservative, and voting records of their members in Congress generally reflect this difference. However, some critics of the U.S. political system think that in the long run there is not a “dime’s worth of difference,” to quote an old saying, between the two parties, as they both ultimately work to preserve corporate interests and capitalism itself (Alexander, 2008). In their view, the Democratic Party is part of the problem, as it tries only to reform the system instead of bringing about the far-reaching changes said to be needed to achieve true equality for all. These criticisms notwithstanding, it is true that neither of the major U.S. parties is as left-leaning as some of the major ones in Western Europe. The two-party system in the United States may encourage middle-of-the road positions, as each party is afraid that straying too far from the middle will cost it votes. In contrast, because many European nations have a greater number of political parties, a party may feel freer to advocate more polarized political views (Muddle, 2007).

Some scholars see this encouragement of middle-of-the-road positions (and thus political stability) as a benefit of the U.S. two-party system, while other scholars view it as a disadvantage because it limits the airing of views that might help a nation by challenging the status quo (Richard, 2010). One thing is clear: in the U.S. two-party model, it is very difficult for a third party to make significant inroads, because the United States lacks a proportional representation system, found in many other democracies, in which parties win seats proportional to their share of the vote (Disch, 2002). Instead, the United States has a winner-takes-all system in which seats go to the candidates with the most votes. Even though the Green Party has millions of supporters across the country, for example, its influence on national policy has been minimal, although it has had more influence in a few local elections. Whether or not the Democratic and Republican parties are that different, U.S. citizens certainly base their party preference in part on their own political ideology.

Political Participation

Perhaps the most important feature of representative democracies is that people vote for officials to represent their views, interests, and needs. For a democracy to flourish, political theorists say, it is essential that “regular” people participate in the political process. The most common type of political participation, of course, is voting; other political activities include campaigning for a candidate, giving money to a candidate or political party, and writing letters to political officials. Despite the importance of these activities in a democratic society, not very many people take part in them. Voting is less common among Americans in comparison to many other nations, as the United States ranks lower than most of the world’s democracies in voter turnout (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 2009).

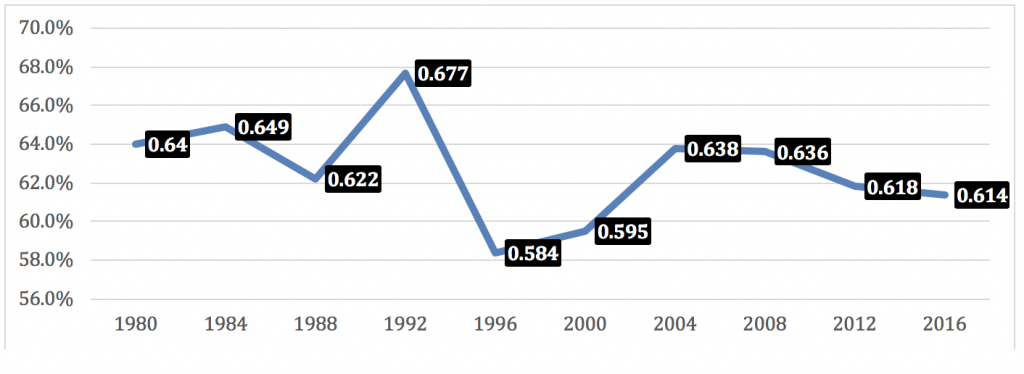

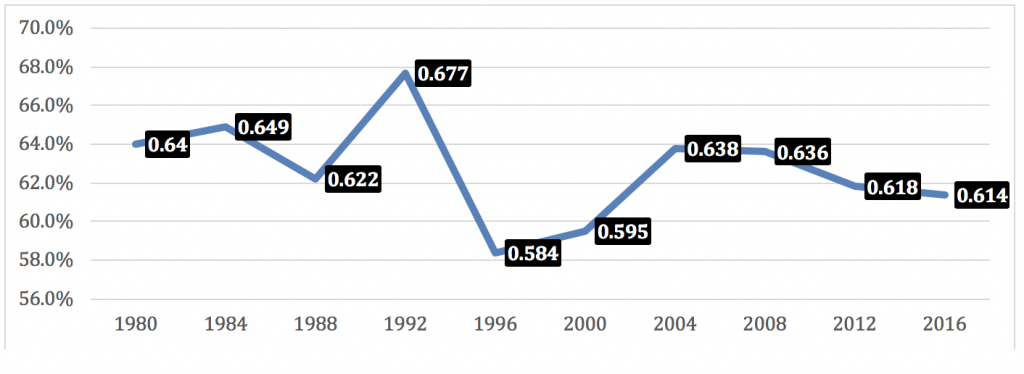

For instance, in 2020, about 66.7% of eligible voters came out to the polls. As shown below in Figure 12.3 “Reported Voting Rates, 1980 – 2016”, this percentage fluctuates, but has been fairly consistent over the past 40 years.

In comparison, countries such as New Zealand and Sweden see significantly higher rates of voter turnout in their general elections. For instance, in the 2017 New Zealand general election, 79.01% of the voting age population cast votes, and in the 2018 Riksdag election (which elects members of the Swedish Parliament), Sweden saw 87.2% of voters come to the polls (Statistiska Centralbyrån, 2018; Votes for Women, 2017).

Figure 12.3 Reported Voting Rates, 1980-2016

In U.S. midterm elections, voter turnout rates are even lower. In the 2018 midterm election, 113 million, or 49% of the voting-age population voted. So, why does the United States not see higher rates of voter turnout? There are numerous explanations available to answer this question.

One explanation relates to differences in practices that make it easier or more difficult to register and vote, which can greatly influence voter turnout (Ellis, Gratschew, Pammett, & Thiessen, 2006). In countries with high voter turnout, practices such as (a) allowing same-day voter registration versus requiring registration a month or more before an election, (b) having multiple voting days versus a single voting day, (c) having the election on a weekend or rest day versus a weekday or workday, (d) having alternative voting procedures (e.g., mail-in voting), and (e) having more polling places increases voter turnout. Nations differ in the extent to which they adopt and use practices that promote registration and voting, and they also differ in the degree to which they use voter information and advertising campaigns and other efforts to encourage voting. In general, these practices and efforts are more often found in other democracies than in the United States.

For example, New Zealand has a well-staffed and well-funded agency, the Electoral Enrolment Centre (EEC), that regularly engages in intensive publicity campaigns to encourage New Zealanders to register to vote. The EEC systematically evaluates the effectiveness of its publicity efforts to ensure that they are as effective as possible, and it makes changes as needed for future efforts. To encourage registration among young people and members of certain ethnic groups that traditionally have low voter registration rates, the EEC visits their households with the hope that personal contact will be more effective in encouraging them to register. The EEC also provides provisional registration for 17-year-olds, who fill out a form with information that is automatically transferred to the official registration list when they turn 18, the New Zealand voting age. The result of such efforts combines with compulsory registration, even though no one has ever been prosecuted for not registering, to produce a voter registration rate of about 95%, one of the highest rates of any democracy (Thiessen, 2006).

In Sweden, a national agency called the Election Authority (translated from its Swedish name, Valmyndigheten) produces information campaigns before each election to educate eligible voters about the candidates and issues at stake. Advertisements and other information are transmitted through television, radio, and Internet outlets and also sent via email. A special effort is made to distribute materials at locations where large groups of people routinely gather, such as businesses, shopping areas, and bus and train stations. Special effort is also made to reach groups with traditionally lower voting rates, including young people, immigrants, and people with disabilities (Lemón & Gratschew, 2006). Elections in Sweden occur on the third Sunday of September; because fewer people work on Sunday, it is thought that Sunday voting increases voter turnout.

Although many factors explain why voter turnout varies among the democracies of the world, many scholars think that the practices and efforts just listed help raise voter turnout. Given this, the United States may be able to increase its own turnout by adopting and/or increasing its use of similar practices and efforts.

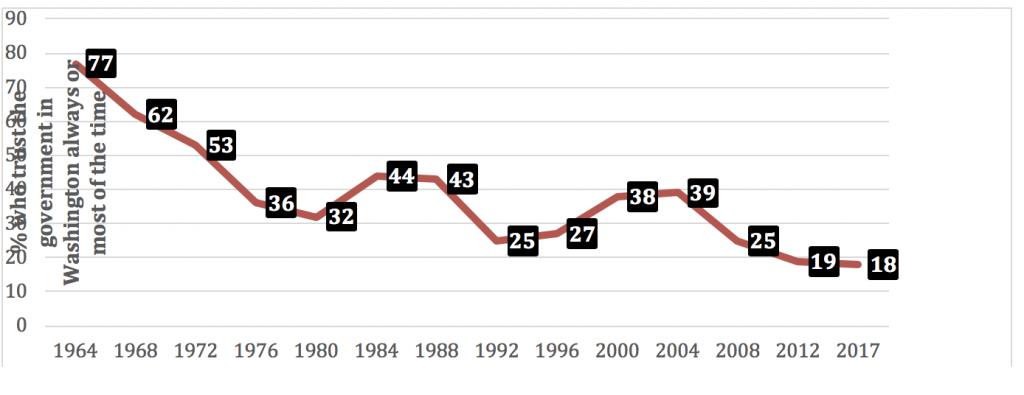

Not only is U.S. voter turnout relatively low in the international sphere, but it has also declined since the 1960s. One factor that explains these related trends is voter apathy, prompted by a lack of faith that voting makes any difference and that government can be helpful. This lack of faith is often called political alienation. As Figure 12.4 “Public Trust in U.S. Government” dramatically shows, lack of faith in the government has dropped drastically since the 1960s, thanks in part, no doubt, to the Vietnam War during the 1960s and 1970s, the Watergate scandal of 1970s, the Iran-Contra scandal of the 1980’s, the attempted impeachment of President Clinton in the 1990’s, the prolonged wars in Iraq and Afghanistan in the 2000’s, economic recession in the last 2000’s, obstruction in Congress over the past several decades, and the like.

Figure 12.4 Public trust in U.S. Government

It is also true that voter turnout varies greatly among Americans. In general, several sets of factors make citizens more likely to vote and otherwise participate in the political process (Burns, Schlozman, & Verba, 2001). These factors, or correlates of political participation, include (a) high levels of resources, including time, money, and communication skills; (b) psychological engagement in politics, including a strong interest in politics and a sense of trust in the political process; and (c) involvement in interpersonal networks of voluntary and other organizations that recruit individuals into political activity. Thus, people who are, for example, wealthier, more interested in politics, and more involved in interpersonal networks are more likely to vote and take part in other political activities than those who are poorer, less interested in politics, and less involved in interpersonal networks. Reflecting these factors, age and high socioeconomic status are especially important predictors of voting and other forms of political participation, as citizens who are older, wealthier, and more educated tend to have more resources, to be more interested in politics and more trustful of the political process, and to be more involved in interpersonal networks. As a result, they are much more likely to vote than people who are younger and less educated (see Table 12.1 “Age, Education, Income, Race-Ethnicity and Percentage Voting, 2016”).

Table 12.1 “Age, Education, Income, Race-Ethnicity and Percentage Voting, 2016”

|

Composition of American Voters by Age, 2016 General Election |

|

|

18-29 years old |

15.7% |

|

30-44 years old |

22.5% |

|

45-64 years old |

37.6% |

|

65+ years old |

24.2% |

|

Composition of American Voters by Educational Level, 2016 General Election |

|

|

Less than High School Diploma |

5.1% |

|

High School Graduate |

24.6% |

|

Some College or Associate’s Degree |

30.8% |

|

Bachelor’s Degree or higher |

39.6% |

|

Composition of American Voters by Income Level, 2016 General Election |

|

|

Annual Family Income Below $20,000 |

5.1% |

|

Annual Family Income $20,000 – 49,999 |

18.3% |

|

Annual Family Income $50,000 – 99,999 |

29.7% |

|

Annual Family Income $100,000 and above |

31.5% |

|

Income Not Reported |

15.4% |

|

Composition of American Voters by Race-Ethnicity, 2016 General Election |

|

|

White, Non-Hispanic |

73.3% |

|

Black, Non-Hispanic |

11.9% |

|

Hispanic/Latino |

9.2% |

|

Other |

5.5% |

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, November 1980–2016. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/P20-582.pdf

The lower voting rates for young people might surprise many readers: because many college students are politically active, it seems obvious that they should vote at high levels. That might be true for some college students, but the bulk of college students are normally not politically active, because they are too busy with their studies, extracurricular activities, and/or work, and because they lack sufficient interest in politics to be active. It is also true that there are many more people aged 18 to 24, the traditional ages for college attendance, than there are actual college students. In view of these facts, the lower voting rates for young people are not that surprising after all.

As shown in Table 12.1 “Age, Education, Income, Race-Ethnicity and Percentage Voting, 2016,” Race and ethnicity also influence voting. In particular, Asians and Latinos vote less often than Blacks and whites among the citizen population. In 2016, among those eligible to vote, roughly 59.6% of Black people and 65.3% of non-Latino whites voted, compared to only 47.6% of Latinos and 49.3% of other races (File, 2017).

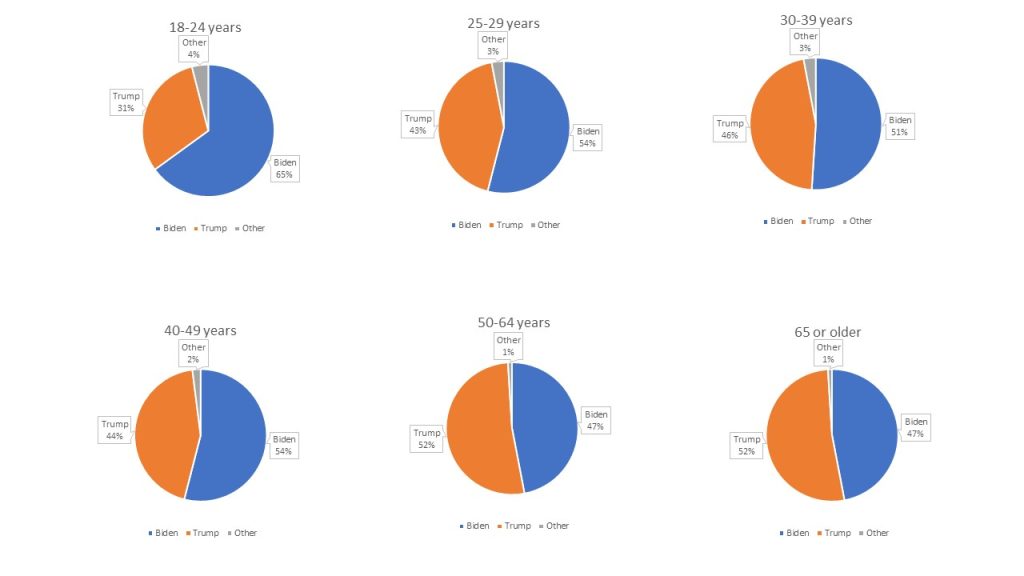

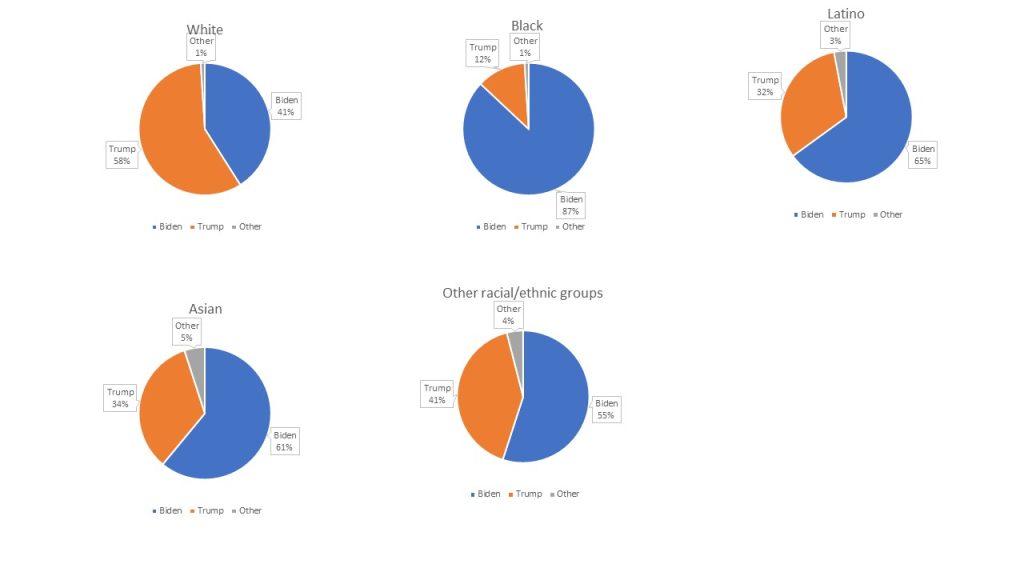

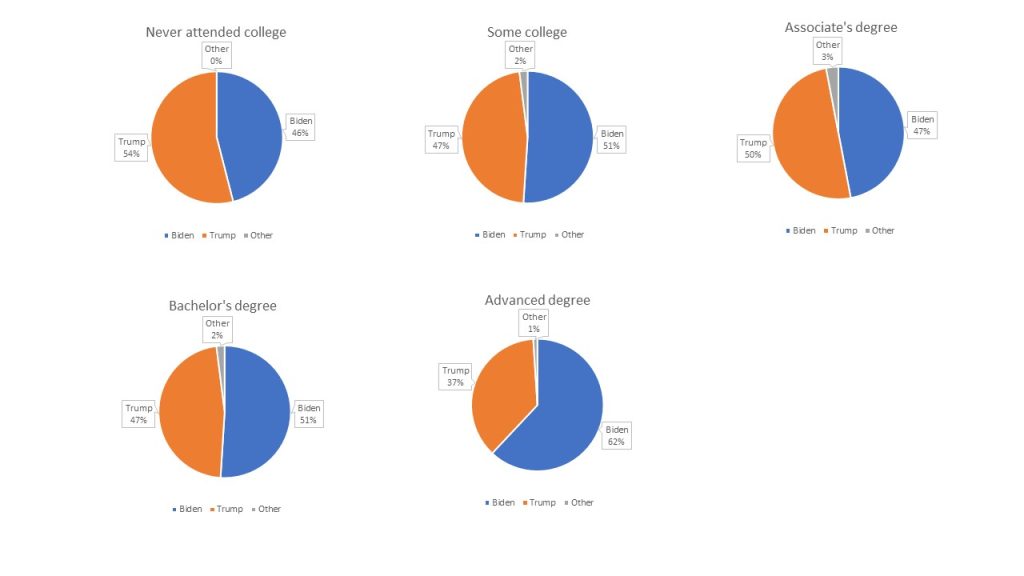

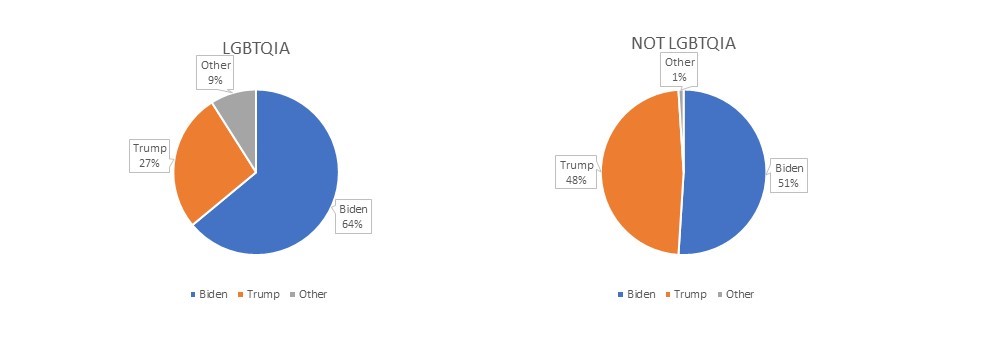

The impact of age, race/ethnicity, education, and other variables on voting rates provides yet another example of the sociological perspective. As should be evident, they show that these aspects of our social backgrounds affect a very important political behavior, voting, even if we are not conscious of this effect. Figures 12.5 “How We Voted by Age in The 2020 Presidential Election” shows that younger people were more likely to vote for Democrat Joe Biden and older people were more likely to vote for Republican Donald Trump. Figure 12.6 “How We Voted by Race/Ethnicity in The 2020 Presidential Election” shows that white people were more likely to vote for Trump and all other racial and ethnic groups were more likely to vote for Biden. Figure 12.7 “How We Voted by Level of Education in The 2020 Presidential Election” shows that people without a bachelor’s degree were more likely to vote for Trump and those with a bachelor’s degree or higher were more likely to vote for Biden. Figure 12.8 “How We Voted by LGBTQIA Status in The 2020 Presidential Election” shows that LGBTQIA people were more likely than non-LGBTQIA people to vote for Biden. These trends are consistent with elections over the last 20 years.

Figure 12.5 How We Voted by Age in The 2020 Presidential Election

Figure 12.6 How We Voted by Race/Ethnicity in The 2020 Presidential Election

Figure 12.7 How We Voted by Level of Education in The 2020 Presidential Election

Figure 12.8 How We Voted by LGBTQIA Status in The 2020 Presidential Election

|

Sociology Making a Difference Felony Disenfranchisement As the text discusses, one of the fundamental principles of a democracy is a right to vote. Political scholars consider voting and other forms of political participation as important activities in their own right but also as effective means to help integrate people into a society and to give them a sense of civic responsibility. Some scholars thus mourn a decline they perceive in civic engagement, as they feel that this decline is undermining social integration and civic responsibility. For these reasons, the disenfranchisement (deprival of voting rights) of convicted felons has attracted much attention in recent years, as most states have laws that take away the right to vote if someone has been convicted of a felony: 48 states prohibit felons from voting while they are incarcerated, with only Maine and Vermont permitting voting while someone is behind bars. Felony disenfranchisement often continues once someone is released from prison, as 23 states prohibit voting while an offender is still on parole; in some states, convicted felons may only vote once released from parole and all fines, fees or restitution payments are made. In 12 states, felons lose voting rights indefinitely for certain crimes such as murder, rape, kidnapping, treason etc. Three states, Kentucky, Virginia and Iowa prohibit those with past felony convictions constitutionally, allowing reprieve only by the authority of the governor granting voting rights. According to The Sentencing Project, a nonprofit organization advocating for sentencing reform, about 5.3 million Americans cannot vote because they have felony convictions. Because felons are disproportionately likely to be poor and Black or Latino, felony disenfranchisement has a disproportionate impact on the Black and Latino communities. An estimated 13% of Black men cannot vote for this reason. Two pioneering scholars on felony disenfranchisement are sociologists Jeff Manza and Christopher Uggen, who documented the impact of felony disenfranchisement on actual election outcomes. They found that felony disenfranchisement affected the results of seven U.S. Senate elections and led to a Republican majority in the U.S. Senate in the early 1980s and then again in the mid-1990s. They also found that felony disenfranchisement almost certainly affected the outcome of a presidential election. In 2000, George W. Bush was declared the winner of the presidential election in Florida, and thus of the whole nation, by only 537 votes. An estimated 600,000 felons were not allowed to vote in Florida in 2000. They were disproportionally Black and would thus have been very likely to vote for Bush’s opponent, Al Gore, if they had been allowed to vote. Felony disenfranchisement thus affected the outcome of the 2000 presidential election and the course of U.S. domestic and foreign policy in the ensuing years. (Manza & Uggen, 2008; The Sentencing Project, 2010) |

12.5 War and Terrorism

War and terrorism are both forms of armed conflict that aim to defeat an opponent. Although war and terrorism have been part of the human experience for thousands of years, their manifestation in the contemporary era is particularly frightening, thanks to ever more powerful weapons, including nuclear arms, that threaten human existence. Because governments play a fundamental role in both war and terrorism, a full understanding of politics and government requires examination of key aspects of these two forms of armed conflict. We start with war and then turn to terrorism.

War

Wars occur both between nations and within nations, when two or more factions engage in armed conflict. War between nations is called international war, while war within nations is called civil war. The most famous civil war to Americans, of course, is the American Civil War, that pitted the North against the South from 1861 through 1865. More than 600,000 soldiers on both sides died on the battlefield or from disease, a number that exceeds American deaths in all the other wars the United States has fought. Globally, more than 100 million soldiers and civilians are estimated to have died during the international and civil wars of the 20th century (Leitenberg, 2006). As Sydney H. Schanberg (2005), a former New York Times reporter who covered the wars in Vietnam and Cambodia, has bluntly observed, “‘History,’ Hegel said, ‘is a slaughterhouse.’ And war is how the slaughter is carried out.”

Explaining War

The enormity of war has stimulated scholarly interest in why humans wage war. A popular explanation for war derives from evolutionary biology. According to this argument, war is part of our genetic heritage because the humans who survived tens of thousands of years ago were those who were most able, by virtue of their temperament and physicality, to take needed resources from other humans they attacked and to defend themselves from attackers. In this manner, a genetic tendency for physical aggression and warfare developed and thus still exists today. In support of this evolutionary argument, some scientists note that chimpanzees and other primates also engage in group aggression against others of their species (Wrangham, 2004).

However, other scientists dispute the evolutionary explanation for several reasons (Begley, 2009; Roscoe, 2007). First, the human brain is far more advanced than the brains of other primates, and genetic instincts that might drive their behavior do not necessarily drive human behavior. Second, many societies studied by anthropologists have been very peaceful, suggesting that a tendency to warfare is more cultural than biological. Third, most people are not violent, and most soldiers have to be resocialized (in boot camp or its equivalent) to overcome their deep moral convictions against killing; if warlike tendencies were part of human genetic heritage, these convictions would not exist.

If warfare is not biological in origin, then it is best understood as a social phenomenon, one that has its roots in the decisions of political and military officials. Sometimes, as with the U.S. entrance into World War II after Pearl Harbor, these decisions are sincere and based on a perceived necessity to defend a nation’s people and resources, and sometimes these decisions are based on cynicism and deceit. A prime example of the latter dynamic is the Vietnam War. The 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, in which Congress authorized President Lyndon Johnson to wage an undeclared war in Vietnam, was passed after North Vietnamese torpedo boats allegedly attacked U.S. ships. However, later investigation revealed that the attack never occurred and that the White House lied to Congress and the American people (Wells, 1994). Four decades later, questions of possible deceit were raised after the United States began the war against Iraq because of its alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction. These weapons were never found, and critics charged that the White House had fabricated and exaggerated evidence of the weapons in order to win public and congressional support for the war (Danner, 2006).

The Cost of War

Beyond its human cost, war also has a heavy financial cost. From 2003 through 2010, the war in Iraq cost the United States some $750 billion (O’Hanlon & Livingston, 2010); from 2001 through 2010, the war in Afghanistan cost the United States more than $300 billion (Mulrine, 2010). These two wars thus cost almost $1.1 trillion combined, for an average of $100 billion per year during this period. This same yearly amount could have paid for one year’s worth (California figures) of all the following (National Priorities Project, 2010):

- 231,000 police officers,

- 11.4 million children receiving low-income health care (Medicaid),

- 2.6 million students receiving full tuition scholarships at state universities,

- 2.5 million Head Start slots for children, and

- 280,000 elementary school teachers.

These trade-offs bring to mind President Eisenhower’s famous observation that “every gun that is made, every warship launched, every rocket fired, signifies in the final sense, a theft from those who hunger and are not fed, those who are cold and are not clothed.” War indeed has a heavy human cost, not only in the numbers of dead and wounded, but also in the diversion of funds from important social functions.

Terrorism

Terrorism is hardly a new phenomenon, but Americans became horrifyingly familiar with it on September 11, 2001, when about 3,000 people died after planes hijacked by Middle Eastern terrorists crashed into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania. The attacks on 9/11 remain in the nation’s consciousness. The attacks also spawned a vast national security network that now reaches into almost every aspect of American life. This network is so secretive, so huge, and so expensive that no one really knows precisely how large it is and how much it costs (Priest & Arkin, 2010). Questions of how best to deal with terrorism continue to be debated, and there are few, if any, easy answers to these questions.

Not surprisingly, sociologists and other scholars have written many articles and books about terrorism. This section draws on their work to discuss the definition of terrorism, the major types of terrorism, explanations for terrorism, and strategies for dealing with terrorism. An understanding of all these issues is essential to make sense of the concern and controversy about terrorism that exists throughout the world today.

Defining Terrorism

There is an old saying that “one person’s freedom fighter is another person’s terrorist.” This saying indicates one of the defining features of terrorism but also some of the problems in coming up with a precise definition of it. Some years ago, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) waged a campaign of terrorism against the British government and its people as part of its effort to drive the British out of Northern Ireland. Many people in Northern Ireland and elsewhere hailed IRA members as freedom fighters, while many other people condemned them as cowardly terrorists. Although most of the world labeled the 9/11 attacks as terrorism, some individuals applauded them as acts of heroism. These examples indicate that there is only a thin line, if any, between terrorism on the one hand and freedom fighting and heroism on the other hand. Just as beauty is in the eyes of the beholder, so is terrorism. The same type of action is either terrorism or freedom fighting, depending on who is characterizing the action.

Although dozens of definitions of terrorism exist, most take into account what are widely regarded as the three defining features of terrorism: (a) the use of violence; (b) the goal of making people afraid; and (c) the desire for political, social, economic, and/or cultural change. A popular definition by political scientist Ted Robert Gurr (1989, p. 201) captures these features: “the use of unexpected violence to intimidate or coerce people in the pursuit of political or social objectives.”

Types of Terrorism

When we think about this definition, 9/11 certainly comes to mind, but there are, in fact, several kinds of terrorism—based on the identity of the actors and targets of terrorism—to which this definition applies. A typology of terrorism again by Gurr (1989) is popular: (a) vigilante terrorism, (b) insurgent terrorism, (c) transnational (or international) terrorism, and (d) state terrorism.

Vigilante terrorism is committed by private citizens against other private citizens. Sometimes the motivation is racial, ethnic, religious, or other hatred, and sometimes the motivation is to resist social change. The violence of racist groups like the Ku Klux Klan was vigilante terrorism, as was the violence used for more than two centuries by white Europeans against Native Americans. What we now call “hate crime” is a contemporary example of vigilante terrorism.

Insurgent terrorism is committed by private citizens against their own government or against businesses and institutions seen as representing the “establishment.” Insurgent terrorism is committed by both left-wing groups and right-wing groups and thus has no political connotation. U.S. history is filled with insurgent terrorism, starting with some of the actions the colonists waged against British forces before and during the American Revolution, when “the meanest and most squalid sort of violence was put to the service of revolutionary ideals and objectives” (Brown, 1989, p. 25). An example here is tarring and feathering: hot tar and then feathers were smeared over the unclothed bodies of Tories. Some of the labor violence committed after the Civil War also falls under the category of insurgent terrorism. A relatively recent example of right-wing insurgent terrorism is the infamous 1995 bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City by Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols that killed 168 people.

Transnational terrorism is committed by the citizens of one nation against targets in another nation. This is the type that has most concerned Americans at least since 9/11, yet 9/11 was not the first time Americans had been killed by international terrorism. A decade earlier, a truck bombing at the World Trade Center killed six people and injured more than 1,000 others. In 1988, 189 Americans were among the 259 passengers and crew who died when a plane bound for New York exploded over Lockerbie, Scotland; agents from Libya were widely thought to have planted the bomb. Despite all these American deaths, transnational terrorism has actually been much more common in several other nations: London, Madrid, Paris and various cities in the Middle East have frequently been the targets of international terrorists.

State terrorism involves violence by a government that is meant to frighten its own citizens and thereby stifle their dissent. State terrorism may involve mass murder, assassinations, and torture. Whatever its form, state terrorism has killed and injured more people than all the other kinds of terrorism combined (Wright, 2007). Genocide, of course is the most deadly type of state terrorism, but state terrorism also occurs on a smaller scale. As just one example, the violent response of Southern white law enforcement officers to the civil rights protests of the 1960s amounted to state terrorism, as officers murdered or beat hundreds of activists during this period. Although state terrorism is usually linked to authoritarian regimes, many observers say that the U.S. government also engaged in state terror during the 19th century, when U.S. troops killed thousands of Native Americans (Brown, 1971).

Explaining Terrorism

Why does terrorism occur? It is easy to assume that terrorists must have psychological problems that lead them to have sadistic personalities, and that they are simply acting irrationally and impulsively. However, most scholars agree that terrorists are psychologically normal despite their murderous violence and, in fact, are little different from other types of individuals who use violence for political ends. As one scholar observed,

Most terrorists are no more or less fanatical than the young men who charged into Union cannon fire at Gettysburg or those who parachuted behind German lines into France. They are no more or less cruel and coldblooded than the Resistance fighters who executed Nazi officials and collaborators in Europe, or the American GI’s ordered to “pacify” Vietnamese villages. (Rubenstein, 1987, p. 5) Contemporary terrorists tend to come from well-to-do families and to be well-educated themselves; ironically, their social backgrounds are much more advantaged in these respects than are those of common street criminals, despite the violence they commit.

If terrorism cannot be said to stem from individuals’ psychological problems, then what are its roots? In answering this question, many scholars say that terrorism has structural roots. In this view, terrorism is a rational response, no matter horrible it may be, to perceived grievances regarding economic, social, and/or political conditions (LaFree & Dugan, 2009). The heads of the U.S. 9/11 Commission, which examined the terrorist attacks of that day, reflected this view in the following assessment:

We face a rising tide of radicalization and rage in the Muslim world—a trend to which our own actions have contributed. The enduring threat is not Osama bin Laden but young Muslims with no jobs and no hope, who are angry with their own governments and increasingly see the United States as an enemy of Islam. (Kean & Hamilton, 2007, p. B1)

As this assessment indicates, structural conditions do not justify terrorism, of course, but they do help explain why some individuals decide to commit it.

Stopping Terrorism

Efforts to stop terrorism take two forms (White, 2012). The first form involves attempts to capture known terrorists and to destroy their camps and facilities and is commonly called a law enforcement or military approach. The second form stems from the recognition of the structural roots of terrorism just described and is often called a structural-reform approach. Each approach has many advocates among terrorism experts, and each approach has many critics.

Law enforcement and military efforts have been known to weaken terrorist forces, but terrorist groups have persisted despite these measures. Worse yet, these measures may ironically inspire terrorists to commit further terrorism and increase public support for their cause. Critics also worry that the military approach endangers civil liberties, as the debate over the U.S. response to terrorism since 9/11 so vividly illustrates (Cole & Lobel, 2007). This debate took an interesting turn in late 2010 amid the increasing use of airport scanners that generate body images. Many people criticized the scanning as an invasion of privacy, and they also criticized the invasiveness of the “pat-down” searches that were used for people who chose not to be scanned (Reinberg, 2010).

In view of all these problems, many terrorism experts instead favor the structural-reform approach, which they say can reduce terrorism by improving or eliminating the conditions that give rise to the discontent that leads individuals to commit terrorism. Here again the assessment of the heads of the 9/11 Commission illustrates this view:

We must use all the tools of U.S. power—including foreign aid, educational assistance and vigorous public diplomacy that emphasizes scholarship, libraries and exchange programs—to shape a Middle East and a Muslim world that are less hostile to our interests and values. America’s long-term security relies on being viewed not as a threat but as a source of opportunity and hope. (Kean & Hamilton, 2007, p. B1)

12.6 Economy and Work in the United States

When we hear the term economy, it is usually in the context of how the economy “is doing”: Is inflation soaring or under control? Is the economy growing or shrinking? Is unemployment rising, declining, or remaining stable? Are new college graduates finding jobs easily or not? All these questions concern the economy, but sociologists define economy more broadly as the social institution that organizes the production, distribution, and consumption of a society’s goods and services. Defined in this way, the economy touches us all.

The economy is composed of three sectors. The primary sector is the part of the economy that takes and uses raw materials directly from the natural environment. Its activities include agriculture, fishing, forestry, and mining. The secondary sector of the economy transforms raw materials into finished products and is essentially the manufacturing industry. Finally, the tertiary sector is the part of the economy that provides services rather than products; its activities include clerical work, health care, teaching, and information technology services.

Globalization refers to the process of integrating governments, cultures, and financial markets through international trade into a single world market. The Internet connects workers and industries across the world, and multinational corporations have plants in many countries that make products for consumers in other countries. Multinational corporations collect resources from a variety of different nations, conduct their business without regard to national borders and concentrate wealth in the hands of high-income nations and wealthy individuals. (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1).

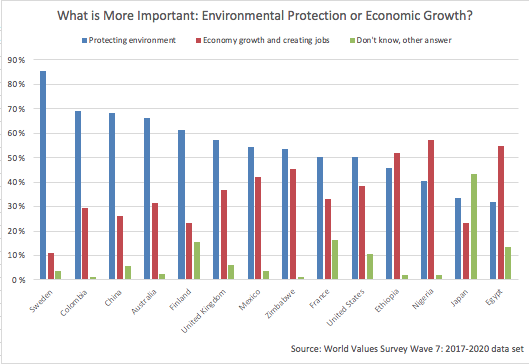

As a result of globalization and expansion of multinational corporations, we see the emergence of global assembly lines, where products are assembled over the course of several international transactions. For instance, Apple designs its next-generation Mac prototype in the United States, components are made in various low- and middle-income nations, such as China, they are then shipped to other low- or middle-income nations, such as Malaysia, for assembly, and tech support is outsourced to India. Another outcome of globalization relates to the fact that what happens economically in one part of the world can greatly affect what happens economically in other parts of the world. If the economies of Asia sour, their demand for U.S. products may decline, forcing a souring of the U.S. economy. A financial crisis in Greece and other parts of Europe during the spring of 2010 caused the stock markets in the United States to plunge. Other concerns associated with globalization relate to fears that multinational corporations can use their vast wealth and resources to control governments to act in their interest rather than that of the local population and that production in low- and middle-income nations, where there is limited regulation, negatively impacts the environment and local economies (Barkan, 2004; 2003). (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/18-2-globalization-and-the-economy). Figure 12.9 “Select Countries Response to What is More Important: Environmental Protection or Economic Growth” show that residents of many countries such as Sweden, Colombia, China, Australia, and Finland are twice as likely to say that protecting the environment is more important than economic growth and job creation. Other countries such as the United Kingdom, Mexico, Zimbabwe, France, the United States, and Japan indicate the environment is more important that the economy. In Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Egypt residents feel the economy and creating jobs is more important than protecting the environment.

Figure 12.9 Select Countries Response to What is More Important: Environmental Protection or Economic Growth

Work in the United States

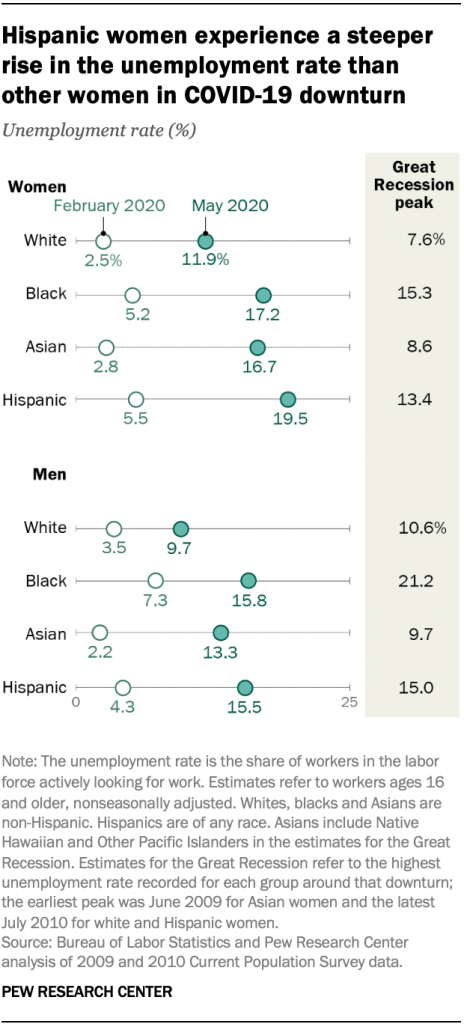

The American Dream has always been based on opportunity. There is a great deal of mythologizing about the energetic upstart who can climb to success based on hard work alone. Common wisdom states that if you study hard, develop good work habits, and graduate high school or, even better, college, then you’ll have the opportunity to land a good job. That has long been seen as the key to a successful life. And although the reality has always been more complex than suggested by the myth, the worldwide recession that began in 2008 took its toll on the American Dream. During the recession, more than 8 million U.S. workers lost their jobs, and unemployment rates surpassed 10 percent on a national level (Openstax). Today, we are facing another economic crisis due the to Covid-19 pandemic. In April 2020, unemployment rates hit 14.4% in the U.S. and has hit women and BIPOC, especially Hispanic/Latina women, at disproportionate rates as indicated in Figure 12.0 (Kochhar, R. 2020).

Figure 12.10 Women and BIPOC, Experience a Steeper Rise in the Unemployment in COVID-19 Downturn

The mix of jobs available in the United States began changing many years before the recession struck, and, as mentioned above, the American Dream has not always been easy to achieve. Geography, race, gender, and other factors have always played a role in the reality of success. More recently, the increased outsourcing—or contracting a job or set of jobs to an outside source—of manufacturing jobs to developing nations has greatly diminished the number of high-paying, often unionized, blue-collar positions available. A similar problem has arisen in the white-collar sector, with many low-level clerical and support positions also being outsourced, as evidenced by the international technical-support call centers in Mumbai, India, and Newfoundland, Canada. The number of supervisory and managerial positions has been reduced as companies streamline their command structures and industries continue to consolidate through mergers. Even highly educated skilled workers such as computer programmers have seen their jobs vanish overseas.

The automation of the workplace, which replaces workers with technology, is another cause of the changes in the job market. Computers can be programmed to do many routine tasks faster and less expensively than people who used to do such tasks. Jobs like bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive tasks on production assembly lines all lend themselves to automation. Envision your local supermarket’s self-scan checkout aisles. The automated cashiers affixed to the units take the place of paid employees. Now one cashier can oversee transactions at six or more self-scan aisles, which was a job that used to require one cashier per aisle.

Despite the ongoing economic recovery, the job market is actually growing in some areas, but in a very polarized fashion. Polarization means that a gap has developed in the job market, with most employment opportunities at the lowest and highest levels and few jobs for those with midlevel skills and education. At one end, there has been strong demand for low-skilled, low-paying jobs in industries like food service and retail. On the other end, some research shows that in certain fields there has been a steadily increasing demand for highly skilled and educated professionals, technologists, and managers. These high-skilled positions also tend to be highly paid (Autor 2010).

The fact that some positions are highly paid while others are not is an example of the class system, an economic hierarchy in which movement (both upward and downward) between various rungs of the socioeconomic ladder is possible. Theoretically, at least, the class system as it is organized in the United States is an example of a meritocracy, an economic system that rewards merit––typically in the form of skill and hard work––with upward mobility. A theorist working in the functionalist perspective might point out that this system is designed to reward hard work, which encourages people to strive for excellence in pursuit of reward. A theorist working in the conflict perspective might counter with the thought that hard work does not guarantee success even in a meritocracy, because social capital––the accumulation of a network of social relationships and knowledge that will provide a platform from which to achieve financial success––in the form of connections or higher education are often required to access the high-paying jobs. Increasingly, we are realizing intelligence and hard work aren’t enough. If you lack knowledge of how to leverage the right names, connections, and players, you are unlikely to experience upward mobility.

With so many jobs being outsourced or eliminated by automation, what kind of jobs are there a demand for in the United States? While fishing and forestry jobs are in decline, in several markets jobs are increasing. These include community and social service, personal care and service, finance, computer and information services, and healthcare.

The professional and related jobs, which include any number of positions, typically require significant education and training and tend to be lucrative career choices. Service jobs, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, can include everything from jobs with the fire department to jobs scooping ice cream (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2010). There is a wide variety of training needed, and therefore an equally large wage potential discrepancy. One of the largest areas of growth by industry, rather than by occupational group (as seen above), is in the health field. This growth is across occupations, from associate-level nurse’s aides to management-level assisted-living staff. As baby boomers age, they are living longer than any generation before, and the growth of this population segment requires an increase in capacity throughout our country’s elder care system, from home healthcare nursing to geriatric nutrition.

Notably, jobs in farming are in decline. This is an area where those with less education traditionally could be assured of finding steady, if low-wage, work. With these jobs disappearing, more and more workers will find themselves untrained for the types of employment that are available.

Another projected trend in employment relates to the level of education and training required to gain and keep a job. As Figure 12.11 shows us, growth rates are higher for those with more education. Those with a professional degree or a master’s degree may expect job growth of 20 and 22 percent respectively, and jobs that require a bachelor’s degree are projected to grow 17 percent. At the other end of the spectrum, jobs that require a high school diploma or equivalent are projected to grow at only 12 percent, while jobs that require less than a high school diploma will grow 14 percent. Quite simply, without a degree, it will be more difficult to find a job. It is worth noting that these projections are based on overall growth across all occupation categories, so obviously there will be variations within different occupational areas. However, once again, those who are the least educated will be the ones least able to fulfill the American Dream.

Figure 12.11 Percent Change in U.S. Employment, by Education Category

In the past, rising education levels in the United States had been able to keep pace with the rise in the number of education-dependent jobs. However, since the late 1970s, men have been enrolling in college at a lower rate than women, and graduating at a rate of almost 10 percent less. The lack of male candidates reaching the education levels needed for skilled positions has opened opportunities for women, minorities, and immigrants (Wang 2011).

When people lose their jobs during a recession or in a changing job market, it takes longer to find a new one, if they can find one at all. If they do, it is often at a much lower wage or not full time. This can force people into poverty. In the United States, we tend to have what is called relative poverty, defined as being unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in your country. This must be contrasted with the absolute poverty that is frequently found in underdeveloped countries and defined as the inability, or near-inability, to afford basic necessities such as food (Byrns 2011).

We cannot even rely on unemployment statistics to provide a clear picture of total unemployment in the United States. First, unemployment statistics do not take into account underemployment, a state in which a person accepts a lower paying, lower status job than their education and experience qualifies them to perform. Second, unemployment statistics only count those:

- who are actively looking for work

- who have not earned income from a job in the past four weeks

- who are ready, willing, and able to work

The unemployment statistics provided by the U.S. government are rarely accurate, because many of the unemployed become discouraged and stop looking for work. Not only that, but these statistics undercount the youngest and oldest workers, the chronically unemployed (e.g., homeless), and seasonal and migrant workers.

A certain amount of unemployment is a direct result of the relative inflexibility of the labor market, considered structural unemployment, which describes when there is a societal level of disjuncture between people seeking jobs and the available jobs. This mismatch can be geographic (they are hiring in California, but most unemployed live in Alabama), technological (skilled workers are replaced by machines, as in the auto industry), or can result from any sudden change in the types of jobs people are seeking versus the types of companies that are hiring.

Because of the high standard of living in the United States, many people are working at full-time jobs but are still poor by the standards of relative poverty. They are the working poor. In terms of employment, the Bureau of Labor Statistics defines the working poor as those who have spent at least 27 weeks working or looking for work, and yet remain below the poverty line. Many of the facts about the working poor are as expected: Those who work only part time are more likely to be classified as working poor than those with full-time employment; higher levels of education lead to less likelihood of being among the working poor; and those with children under 18 are four times more likely than those without children to fall into this category.