11

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Define sex and gender and understand the social construction of gender vs sex as a biological concept.

- Discuss gender socialization, and how family, peers, schools, the mass media, and religion are social agents for gendered pathways.

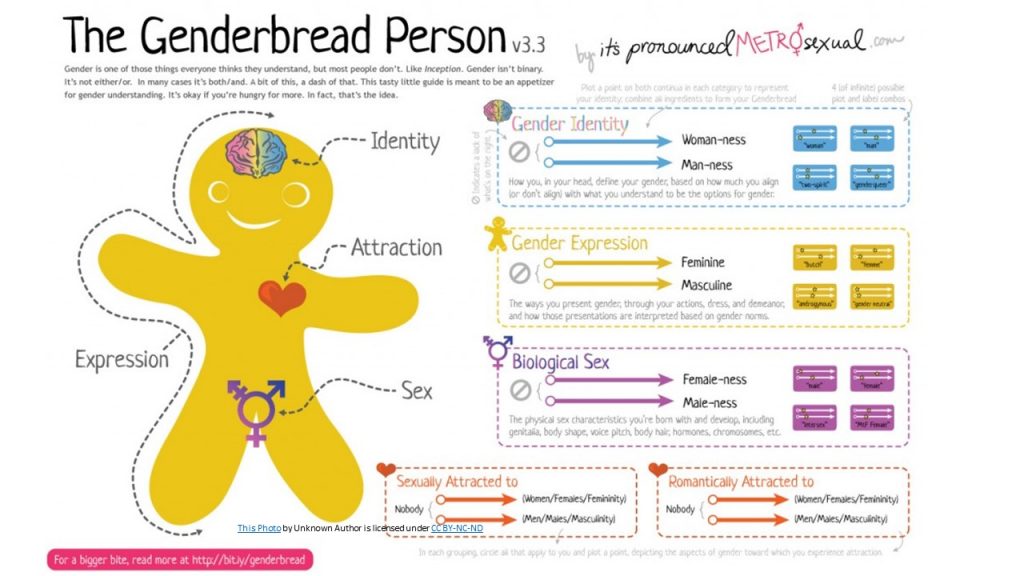

- Define gender roles, gender expectations, and gender identity. Gain an understanding of the term gender spectrum.

- Understand and discuss the role of homophobia and heterosexism in society

- Distinguish the meanings of transgendered, transsexual, and homosexual identities

- Understand different attitudes associated with sex and sexuality

- Discuss theoretical perspectives on gender, sex and sexuality

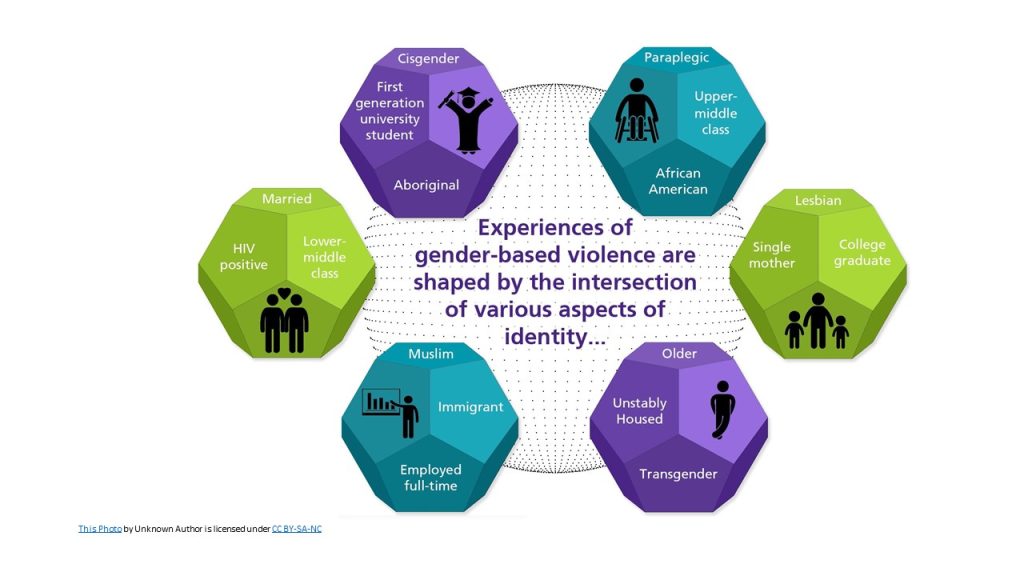

- Define intersectionality

Social Issues in the News

“Pandemic taking disproportionate toll on moms” reads the headline of a November 23, 2020 MLive article. In 2020 the coronavirus became a global pandemic closing many schools and other businesses. Many workers began working from home and parents with children at home have been especially burdened as they struggle to meet the demands of their jobs and their children. According to the US. Department of Labor, in September 2020, federal unemployment statistics showed that 216,000 men and 865,000 women were laid off or left the workforce, often to care for children who can no longer attend school in person. In Michigan, specifically, from February to September, employment fell by 269,000, or 11.9%, for women compared to 26,000 or 1.1%, for men. Furthermore, the number of men in the labor force grew by 70,000 while the number of women fell by 180,000. “Pandemic taking disproportionate toll on moms” by Rylie Murdock In this chapter, we will address gender inequalities such as this.

11.1 Understanding Sex and Gender

Although the terms sex and gender are sometimes used interchangeably and do in fact complement each other, they nonetheless refer to different aspects of what it means to be a woman or man in any society.

Sex refers to the anatomical and other biological differences between the people we call females and males that are determined at the moment of conception and develop in the womb and throughout childhood and adolescence. Females, have two X chromosomes, while males have one X chromosome and one Y chromosome. From this basic genetic difference spring other biological differences. The first to appear are the different genitals that boys and girls develop in the womb and that the doctor (or midwife) and parents look for when a baby is born (assuming the baby’s sex is not already known from ultrasound or other techniques) so that the momentous announcement, “It’s a boy!” or “It’s a girl!” can be made. The genitalia present at birth are considered primary sex characteristics, while the other differences that develop later in life during puberty are called secondary sex characteristics and stem from hormonal differences between the two sexes. In this difficult period of adolescents’ lives, boys generally acquire deeper voices, more body hair, and more muscles from their flowing testosterone. Girls develop breasts and wider hips and begin menstruating as nature prepares them for possible pregnancy and childbirth. These basic biological differences between the sexes affect many people’s perceptions of femininity, masculinity and what it means to be female or male, as we shall soon discuss.

The dichotomous view of gender (the notion that someone is either male or female) is specific to certain cultures and is not universal. In some cultures gender is viewed as fluid. In the past, some anthropologists used the term berdache to refer to individuals who occasionally or permanently dressed and lived as a different gender. The practice has been noted among certain Native American tribes (Jacobs, Thomas, and Lang 1997). Samoan culture accepts what Samoans refer to as a “third gender.” Fa’afafine, which translates as “the way of the woman,” is a term used to describe individuals who are born biologically male but embody both masculine and feminine traits. Fa’afafines are considered an important part of Samoan culture. Individuals from other cultures may mislabel them as homosexuals because Fa’afafines have a varied sexual life that may include men and women (Poasa 1992). (OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/12-1-sex-and-gender).

Gender as a Social Construction

Sex is a biological concept and gender is a social concept. Gender refers to the social and cultural differences a society assigns to feminine and masculine characteristics based on biological sex. This should not be confused with sexuality or sexual orientation. A related concept, gender roles, refers to a society’s expectations of people’s behavior and attitudes based on whether they identify as female or male. Understood in this way, gender, like race as discussed in Chapter 6 “Deviance, Crime, and Social Control”, is a social construction. How we think and behave as females and males is not etched in stone by our biology but rather is a result of how society expects us to think and behave based on what sex we are. As we grow up, we learn these expectations as we develop our gender identity, or our beliefs about ourselves as being females or males, both female and male, or neither female or male.

Figure 11.1 Genderbread Person

These expectations are called femininity and masculinity. Femininity refers to the cultural expectations we have of girls and women, while masculinity refers to the expectations we have of boys and men. A familiar nursery rhyme nicely summarizes these two sets of traits:

What are little boys made of?

Snips and snails,

And puppy dog tails,

That’s what little boys are made of.

What are little girls made of?

Sugar and spice,

And everything nice,

That’s what little girls are made of.

As this nursery rhyme suggests, our traditional notions of femininity and masculinity indicate that we think females and males are fundamentally different from each other. In effect, we think of them as two sides of the same coin of being human. What we traditionally mean by femininity is captured in the adjectives, both positive and negative, we traditionally ascribe to women: gentle, sensitive, nurturing, delicate, graceful, cooperative, decorative, dependent, emotional, passive, and weak. What we traditionally mean by masculinity is captured in the adjectives, again both positive and negative, our society traditionally ascribes to men: strong, assertive, brave, active, independent, intelligent, competitive, insensitive, unemotional, and aggressive.

These traits might sound like stereotypes of females and males in today’s society, and to some extent they are, but differences between men and women in attitudes and behavior do in fact exist (Aulette, Wittner, & Blakeley, 2009). For example, women cry more often than men do. Men are more physically violent than women. Women take care of children more than men do. Women smile more often than men. Men curse more often than women. When women talk with each other, they are more likely to talk about their personal lives than men are when they talk with each other (Tannen, 2001). The two sexes even differ when they hold a cigarette. When a woman holds a cigarette, she usually has the palm of her cigarette-holding hand facing upward. When a man holds a cigarette, he usually has his palm facing downward.

During the course of one’s lifetime it is possible to identify with more than one gender. Thus far, in the chapter only two genders have been mentioned. Gender binary is the term used when a society only recognizes two genders. It is possible for someone not to identify strictly as either a boy (man) or girl (woman), they could choose to identify as both genders, or a completely different gender, and this is considered having a non-binary gender identity. The term for people who do not identify with a gender at all is agender. Not being limited to two gender possibilities is known as gender spectrum.

Sexual Orientation

A person’s sexual orientation is their physical, mental, emotional, and sexual attraction to a particular sex (male and/or female). Sexual orientation is typically divided into several categories: heterosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the other sex; homosexuality, the attraction to individuals of the same sex; bisexuality, the attraction to individuals of either sex; asexuality, a lack of sexual attraction or desire for sexual contact; pansexuality, an attraction to people regardless of sex, gender, gender identity, or gender expression; and queer, an umbrella term used to describe sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression. Heterosexuals and homosexuals are referred to as “straight” and “gay,” respectively but more inclusive terminology is needed. Proper terminology includes the acronyms LGBT, LGBTQ and LGBTQIA, which stands for “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender” and “Queer” or “Questioning” when the Q is added. More recently the I and A have been added to include “Intersex and Asexual.” We will use the more inclusive LGBTQIA. The United States is a heteronormative society, meaning many people assume heterosexual orientation is biologically determined and unambiguous. Consider that LGBTQIA people are often asked, “When did you know you were gay?” but heterosexuals are rarely asked, “When did you know that you were straight?” (Ryle 2011).(OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/12-1-sex-and-gender)

According to current scientific understanding, individuals are usually aware of their sexual orientation between middle childhood and early adolescence (American Psychological Association 2008). They do not have to participate in sexual activity to be aware of these emotional, romantic, and physical attractions; people can be celibate and still recognize their sexual orientation, and may have very different experiences of discovering and accepting their sexual orientation. At the point of puberty, some may be able to announce their sexual orientations, while others may be unready or unwilling to make their homosexuality or bisexuality known since it goes against U.S. society’s historical norms (APA 2008).(OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/12-1-sex-and-gender)

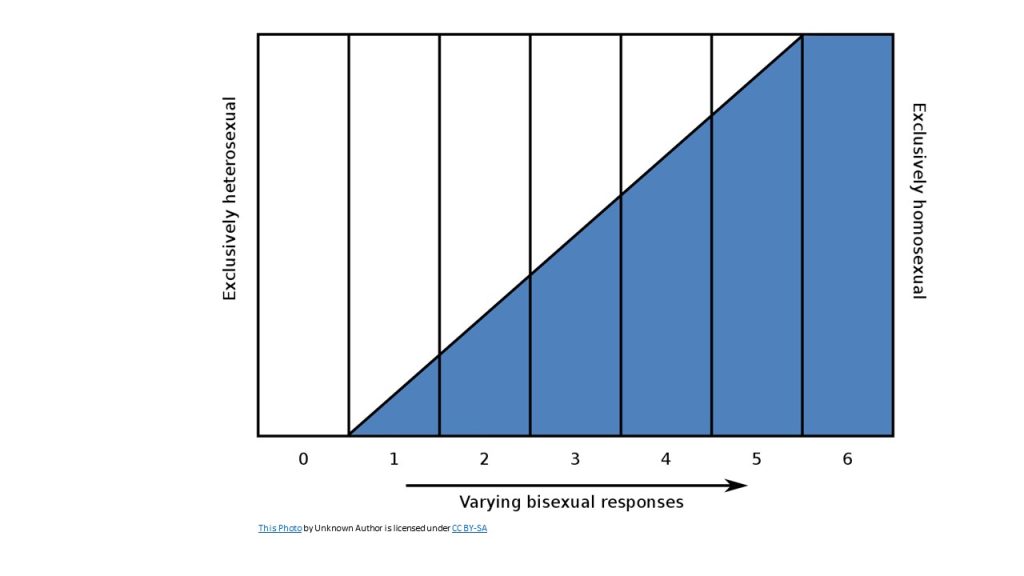

Alfred Kinsey was among the first to conceptualize sexuality as a continuum rather than a strict dichotomy of gay or straight. He created a six-point rating scale (Figure 11.2) that ranges from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. See the figure below. In his 1948 work Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, Kinsey writes, “Males do not represent two discrete populations, heterosexual and homosexual. The world is not to be divided into sheep and goats … The living world is a continuum in each and every one of its aspects” (Kinsey 1948).(OpenStax, Sociology 2e, Attribution International (CC BY 4.0); download for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/12-1-sex-and-gender)

Figure 11.2 Kinsey 6-point Scale

The Development of Gender Differences

What accounts for differences in female and male behavior and attitudes? Do the biological differences between the sexes account for other differences? Or do these latter differences stem, as most sociologists think, from cultural expectations and from differences in the ways in which the sexes are socialized? These are critical questions, for they ask whether the differences between boys and girls and women and men stem more from biology or from society. Biological explanations for human behavior implicitly support the status quo. If we think behavioral and other differences between the sexes are due primarily to their respective biological makeups, we are saying that these differences are inevitable or nearly so and that any attempt to change them goes against biology and will likely fail.

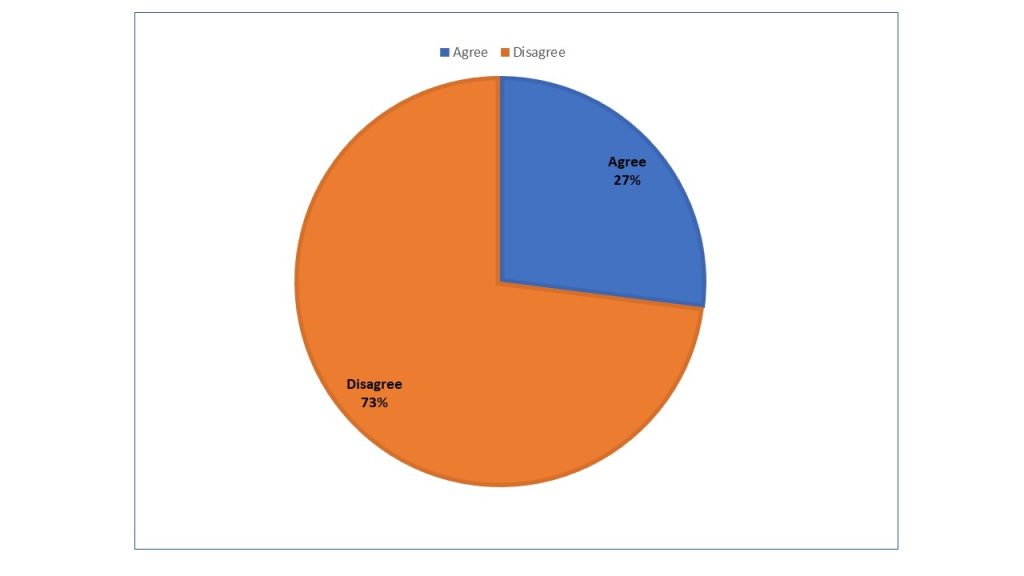

Figure 11.3 Belief That Women Should Stay at Home; Agreement or Disagreement with Statement that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.”

As an example, consider the obvious biological fact that women bear and nurse children and men do not. Couple this with the common view that women are gentler and more nurturing than men, and we end up with a “biological recipe” for women to be the primary caretakers of children. Many people think this means women are therefore much better suited than men to take care of children once they are born, and that the family might be harmed if mothers work outside the home or if fathers are the primary caretakers. Figure 11.2 “Belief That Women Should Stay at Home” shows that 27% of the public agrees or strongly agrees that “it is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” To the extent this belief exists, women may not want to work outside the home or, if they choose to do so, they face difficulties from employers, family, and friends. Conversely, men may not even think about wanting to stay at home and may themselves face difficulties from employees, family, and friends if they want to do so. A belief in a strong biological basis for differences between women and men implies, then, that there is little we can or should do to change these differences. It implies that “anatomy is destiny,” and destiny is, of course, by definition inevitable.

This implication makes it essential to understand the extent to which gender differences do, in fact, stem from biological differences between the sexes or, instead, stem from cultural and social influences. If biology is paramount, then gender differences are perhaps inevitable and the status quo will remain. If culture and social influences matter much more than biology, then gender differences can change and the status quo may give way. With this backdrop in mind, let’s turn to the biological evidence for behavioral and other differences between the sexes and then examine the evidence for their social and cultural roots.

Biology and Gender

Several biological explanations for gender roles exist, and we discuss two of the most important ones here. One explanation is from the related fields of sociobiology and evolutionary psychology (Workman & Reader, 2009) and argues an evolutionary basis for traditional gender roles.

Scholars advocating this view reason as follows (Barash, 2007; Thornhill & Palmer, 2000). In prehistoric societies, few social roles existed. A major role centered on relieving hunger by hunting or gathering food. The other major role centered on bearing and nursing children. Because only women could perform this role, they were also the primary caretakers for children for several years after birth. And because women were frequently pregnant, their roles as mothers confined them to the home for most of their adulthood. Meanwhile, men were better suited than women for hunting because they were stronger and quicker than women. In prehistoric societies, then, biology was indeed destiny: for biological reasons, men in effect worked outside the home (hunted), while women stayed at home with their children.

Evolutionary reasons also explain why men are more violent than women. In prehistoric times, men who were more willing to commit violence against and even kill other men would “win out” in the competition for female mates. They thus were more likely than less violent men to produce offspring, who would then carry these males’ genetic violent tendencies. By the same token, men who were prone to rape women were more likely to produce offspring, who would then carry these males’ “rape genes.” This early process guaranteed that rape tendencies would be biologically transmitted and thus provided a biological basis for the current level of rape.

If the human race evolved along these lines, sociobiologists and evolutionary psychologists continue, natural selection favored those societies where men were stronger, braver, and more aggressive and where women were more fertile and nurturing. Such traits over the millennia became fairly instinctual, meaning that men’s and women’s biological natures evolved differently. Men became, by nature, more assertive, daring, and violent than women, and women are, by nature, more gentle, nurturing, and maternal than men. To the extent this is true, these scholars add, traditional gender roles for women and men make sense from an evolutionary standpoint, and attempts to change them go against the sexes’ biological natures. This in turn implies that existing gender inequality must continue because it is rooted in biology.

Critics challenge the evolutionary explanation on several grounds (Hurley, 2007; Buller, 2006; Begley, 2009). First, much greater gender variation in behavior and attitudes existed in prehistoric times than the evolutionary explanation assumes. Second, even if biological differences did influence gender roles in prehistoric times, these differences are largely irrelevant in today’s world, in which, for example, physical strength is not necessary for survival. Third, human environments throughout the millennia have simply been too diverse to permit the simple, straightforward biological development that the evolutionary explanation assumes. Fourth, evolutionary arguments implicitly justify existing gender inequality by implying the need to confine women and men to their traditional roles.

Recent anthropological evidence also challenges the evolutionary argument that men’s tendency to commit violence, including rape, was biologically transmitted. This evidence instead finds that violent men have trouble finding female mates who would want them and that the female mates they find and the children they produce are often killed by rivals to the men. The recent evidence also finds those rapists’ children are often abandoned and then die. As one anthropologist summarizes the rape evidence, “The likelihood that rape is an evolved adaptation [is] extremely low. It just wouldn’t have made sense for men in the [prehistoric epoch] to use rape as a reproductive strategy, so the argument that it’s preprogrammed into us doesn’t hold up” (Begley, 2009, p. 54).

A second biological explanation for traditional gender roles centers on hormones and specifically on testosterone, the so-called male hormone. One of the most important differences between males and females in the United States and many other societies is their level of aggression. Simply put, males are much more physically aggressive than females and in the United States commit about 85%–90% of all violent crimes. Why is this so? This gender difference is often attributed to males’ higher levels of testosterone (Mazur, 2009).

To see whether testosterone does indeed raise aggression, researchers typically assess whether males with higher testosterone levels are more aggressive than those with lower testosterone levels. Several studies find that this is indeed the case. For example, a widely cited study of Vietnam-era male veterans found that those with higher levels of testosterone had engaged in more violent behavior (Booth & Osgood, 1993). However, this correlation does not necessarily mean that their testosterone increased their violence: as has been found in various animal species, it is also possible that their violence increased their testosterone. Because studies of human males can’t for ethical and practical reasons manipulate their testosterone levels, the exact meaning of the results from these testosterone-aggression studies must remain unclear, according to a review sponsored by the National Academy of Sciences (Miczek, Mirsky, Carey, DeBold, & Raine, 1994).

Another line of research on the biological basis for sex differences in aggression involves children, including some as young as ages 1 or 2, in various situations (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008). They might be playing with each other, interacting with adults, or writing down solutions to hypothetical scenarios given to them by a researcher. In most of these studies, boys are more physically aggressive in thought or deed than girls, even at a very young age. Other studies are more experimental in nature. In one type of study, a toddler will be playing with a toy, only to have it removed by an adult. Boys typically tend to look angry and try to grab the toy back, while girls tend to just sit there and whimper. Because these gender differences in aggression are found at very young ages, researchers often say they must have some biological basis. However, critics of this line of research counter that even young children have already been socialized along gender lines (Begley, 2009; Eliot, 2009), a point to which we return later. To the extent this is true, gender differences in children’s aggression may simply reflect socialization and not biology.

In sum, biological evidence for gender differences certainly exists, but its interpretation remains very controversial. It must be weighed against the evidence, to which we next turn, of cultural variations in the experience of gender and of socialization differences by gender. One thing is clear: to the extent we accept biological explanations for gender, we imply that existing gender differences and gender inequality must continue to exist. This implication prompts many social scientists to be quite critical of the biological viewpoint. As Linda L. Lindsey (2011, p. 52) notes, “Biological arguments are consistently drawn upon to justify gender inequality and the continued oppression of women.” In contrast, cultural and social explanations of gender differences and inequality promise some hope for change. Let’s examine the evidence for these explanations.

Culture and Gender

Some of the most compelling evidence against a strong biological determination of gender roles comes from anthropologists, whose work on preindustrial societies demonstrates some striking gender variation from one culture to another. This variation underscores the impact of culture on how females and males think and behave.

Margaret Mead (1935) was one of the first anthropologists to study cultural differences in gender. In New Guinea she found three tribes—the Arapesh, the Mundugumor, and the Tchambuli—whose gender roles differed dramatically. In the Arapesh both sexes were gentle and nurturing. Both women and men spent much time with their children in a loving way and exhibited what we would normally call maternal behavior. In the Arapesh, then, different gender roles did not exist, and in fact, both sexes conformed to what Americans would normally call the female gender role.The situation was the reverse among the Mundugumor. Here both men and women were fierce, competitive, and violent. Both sexes seemed to almost dislike children and often physically punished them. In the Mundugumor society, then, different gender roles also did not exist, as both sexes conformed to what we Americans would normally call the male gender role.

In the Tchambuli, Mead finally found a tribe where different gender roles did exist. One sex was the dominant, efficient, assertive one and showed leadership in tribal affairs, while the other sex liked to dress up in frilly clothes, wear makeup, and even giggle a lot. Here, then, Mead found a society with gender roles similar to those found in the United States, but with a surprising twist. In the Tchambuli, women were the dominant, assertive sex that showed leadership in tribal affairs, while men were the ones wearing frilly clothes and makeup.

Mead’s research caused a firestorm in scholarly circles, as it challenged the biological view on gender that was still very popular when she went to New Guinea. Other anthropologists note that much subsequent research has found that gender-linked attitudes and behavior do differ widely from one culture to another, confirming Mead’s findings (Morgan, 1989). Thus, the impact of culture on what it means to be a female or male cannot be ignored.

Extensive evidence of this impact comes from anthropologist George Murdock, who created the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample of almost 200 preindustrial societies studied by anthropologists. Murdock (1937) found that some tasks in these societies, such as hunting and trapping, are almost always done by men, while other tasks, such as cooking and fetching water, are almost always done by women. These patterns provide evidence for the evolutionary argument presented earlier, as they probably stem from the biological differences between the sexes. Even so there were at least some societies in which women hunted and in which men cooked and fetched water.

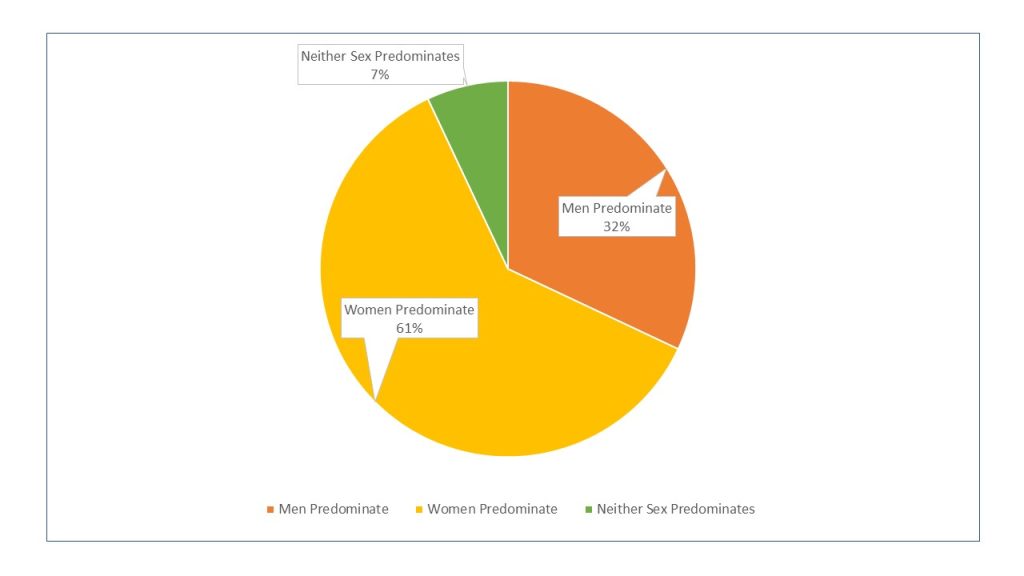

More importantly, Murdock found much greater gender variation in several of the other tasks he studied, including planting crops, milking, and generating fires. Men primarily performed these tasks in some societies, women primarily performed them in other societies, and in still other societies both sexes performed them equally. Figure 11.4 “Gender Responsibility for Weaving” shows the gender responsibility for yet another task, weaving. Women are the primary weavers in about 61% of the societies that do weaving, men are the primary weavers in 32%, and both sexes do the weaving in 7% of the societies. Murdock’s findings illustrate how gender roles differ from one culture to another and imply they are not biologically determined.

Figure 11.4 Gender Responsibility for Weaving

Anthropologists since Mead and Murdock have continued to investigate cultural differences in gender. Some of their most interesting findings concern gender and sexuality (Morgan, 1989; Brettell & Sargent, 2009). Although all societies distinguish “femaleness” and “maleness,” additional gender categories exist in some societies. The Mohave, a Native American tribe, for example, recognize four genders: a woman, a woman who acts like a man, a man, and a man who acts like a woman. In some societies, a third, intermediary gender category is recognized. Anthropologists call this category the berdache, who is usually a man who takes on a woman’s role. This intermediary category combines aspects of both femininity and masculinity of the society in which it is found and is thus considered an androgynous gender. Although some people in this category are born as intersexed individuals, meaning they have ambiguous genitalia, many are born biologically as one sex or the other but adopt an androgynous identity.

An example of this intermediary gender category may be found in India, where the hijra role involves males who wear women’s clothing and identify as women (Reddy, 2006). The hijra role is an important part of Hindu mythology, in which androgynous figures play key roles both as humans and as gods. Today people identified by themselves and others as hijrjas continue to play an important role in Hindu practices and in Indian cultural life in general. Serena Nanda (1997, pp. 200–201) calls hijras “human beings who are neither man nor woman” and says they are thought of as “special, sacred beings” even though they are sometimes ridiculed and abused.

Anthropologists have found another androgynous gender composed of women warriors in 33 Native American groups in North America. Walter L. Williams (1997) calls these women “amazons” and notes that they dress like men and sometimes even marry women. In some tribes, girls exhibit such “masculine” characteristics from childhood, while in others they may be recruited into “amazonhood.” In the Kaska Indians, for example, a married couple with too many daughters would select one to “be like a man.” When she was about 5 years of age, her parents would begin to dress her like a boy and have her do male tasks. Eventually she would grow up to become a hunter.

The androgynous genders found by anthropologists remind us that gender is a social construction and not just a biological fact. If culture does affect gender roles, socialization is the process through which culture has this effect. What we experience as girls and boys strongly influences how we develop as women and men in terms of behavior and attitudes. To illustrate this important dimension of gender, let’s turn to the evidence on socialization.

Socialization and Gender

Chapter 2 “Culture” identified several agents of socialization, including the family, peers, schools, the mass media, and religion. While that chapter’s discussion focused on these agents’ impact on socialization in general, ample evidence of their impact on gender-role socialization also exists. Such socialization us to develop our gender identity (Andersen & Hysock, 2009).

Families

Socialization into gender roles begins in infancy, as almost from the moment of birth parents begin to socialize their children as boys or girls without even knowing it (Begley, 2009; Eliot, 2009). Many studies document this process (Lindsey, 2011). Parents commonly describe their infant daughters as pretty, soft, and delicate and their infant sons as strong, active, and alert, even though neutral observers find no such gender differences among infants when they do not know the infants’ sex. From infancy on, parents play with and otherwise interact with their daughters and sons differently. They play more roughly with their sons—for example, by throwing them up in the air or by gently wrestling with them—and more quietly with their daughters. When their infant or toddler daughters cry, they warmly comfort them, but they tend to let their sons cry longer and to comfort them less. They give their girls dolls to play with and their boys “action figures” and toy guns. While these gender differences in socialization are probably smaller now than a generation ago, they certainly continue to exist. Go into a large toy store and you will see pink aisles of dolls and cooking sets and blue aisles of action figures, toy guns, and related items.

Peers

Peer influences also encourage gender socialization. As they reach school age, children begin to play different games based on their gender (see the “Sociology Making a Difference” below). Boys tend to play sports and other competitive team games governed by inflexible rules and relatively large numbers of roles, while girls tend to play smaller, cooperative games such as hopscotch and jumping rope with fewer and more flexible rules. Although girls are much more involved in sports now than a generation ago, these gender differences in their play as youngsters persist and continue to reinforce gender roles. For example, they encourage competitiveness in boys and cooperation and trust among girls. Boys who are not competitive risk being called “sissy” or other words by their peers. The patterns we see in adult males and females thus have their roots in their play as young children (King, Miles, & Kniska, 1991).

Schools

School is yet another agent of gender socialization (Klein, 2007). First of all, school playgrounds provide a location for the gender-linked play activities just described to occur. Second, and perhaps more important, teachers at all levels treat their female and male students differently in subtle ways of which they are probably not aware. They tend to call on boys more often to answer questions in class and to praise them more when they give the right answer. They also give boys more feedback about their assignments and other school work (Sadker & Sadker, 1994). At all grade levels, many textbooks and other books still portray people in gender-stereotyped ways. It is true that the newer books do less of this than older ones, but the newer books still contain some stereotypes, and the older books are still used in many schools.

Mass Media

Gender socialization also occurs through the mass media (Dow & Wood, 2006). On children’s television shows, the major characters are male. On Nickelodeon, for example, the very popular SpongeBob SquarePants is a male, as are his pet snail, Gary; his best friend, Patrick Star; their neighbor, Squidward Tentacles; and SpongeBob’s employer, Eugene Crabs. Of the major characters in Bikini Bottom, only Sandy Cheeks is a female. For all its virtues, Sesame Street features Bert, Ernie, Cookie Monster, and other male characters. Most of the Muppets are males, and the main female character, Miss Piggy, depicted as vain and jealous, is hardly an admirable female role model. As for adults’ prime-time television, more men than women continue to fill more major roles in weekly shows. Women are also often portrayed as unintelligent or frivolous individuals who are there more for their looks than for anything else. Television commercials reinforce this image (Yoder, Christopher, & Holmes, 2008). Cosmetics ads abound, suggesting not only that a major task for women is to look good but also that their sense of self-worth stems from looking good. Other commercials show women becoming ecstatic over achieving a clean floor or sparkling laundry. Judging from the world of television commercials, then, women’s chief goals in life are to look good and to have a clean house. At the same time, men’s chief goals, judging from many commercials, are to drink beer and drive sports cars and trucks.

Women’s and men’s magazines reinforce these gender images (Milillo, 2008). Most of the magazines intended for teenaged girls and adult women are filled with pictures of thin, beautiful models, advice on dieting, cosmetics ads, and articles on how to win and please your man. Conversely, the magazines intended for teenaged boys and men are filled with ads and articles on cars and sports, advice on how to succeed in careers and other endeavors, and pictures of thin, beautiful (and sometimes nude) women. These magazine images again suggest that women’s chief goals are to look good and to please men and that men’s chief goals are to succeed, win over women, and live life in the fast lane.

Religion

Another agent of socialization, religion, also contributes to traditional gender stereotypes. Many traditional interpretations of the Bible yield the message that women are subservient to men (Tanenbaum, 2009). This message begins in Genesis, where the first human is Adam, and Eve was made from one of his ribs. The major figures in the rest of the Bible are men, and women are for the most part depicted as wives, mothers, temptresses, and prostitutes; they are praised for their roles as wives and mothers and condemned for their other roles. More generally, women are constantly depicted as the property of men. The Ten Commandments includes a neighbor’s wife with his house, ox, and other objects as things not to be coveted (Exodus 20:17), and many passages say explicitly that women belong to men, such as this one from the New Testament:

Wives be subject to your husbands, as to the Lord. For the husband is the head of the wife as Christ is the head of the Church. As the Church is subject to Christ, so let wives also be subject in everything to their husbands. (Ephesians 5:22–24)

Several passages in the Old Testament justify the rape and murder of women and girls. The Koran, the sacred book of Islam, also contains passages asserting the subordinate role of women (Mayer, 2009).

This discussion suggests that religious people should believe in traditional gender views more than less religious people, and research confirms this relationship (Morgan, 1988). Research from the General Social Survey confirms this assumption, finding a correlation between frequency of prayer and acceptance of traditional gender roles in the family. Less than 15% of respondents who never or infrequently pray accept traditional gender roles in the family, while more than 30% of those who pray daily accept these traditional roles (2018).

A Final Word on the Sources of Gender

Scholars in many fields continue to debate the relative importance of biology and of culture and socialization for how we behave and think as girls and boys and as women and men. The biological differences between females and males lead many scholars and no doubt much of the public to assume that masculinity and femininity are to a large degree biologically determined. In contrast, anthropologists, sociologists, and other social scientists tend to view gender as a social construction. Even if biology does matter for gender, they say, the significance of culture and socialization should not be underestimated. To the extent that gender is indeed shaped by society and culture, it is possible to change gender and to help bring about a society where both men and women have more opportunity to achieve their full potential.

11.2 Feminism and Sexism

Recall that more than one-third of the public (as measured in the General Social Survey in 2018) agrees with the statement, “It is much better for everyone involved if the man is the achiever outside the home and the woman takes care of the home and family.” Do you agree or disagree with this statement? If you are like the majority of college students, you disagree.

Today a lot of women, and some men, will say, “I’m not a feminist, but…,” and then go on to add that they hold certain beliefs about women’s equality and traditional gender roles that actually fall into a feminist framework. Their reluctance to self-identify as feminists underscores the negative image that feminists and feminism hold but also suggests that the actual meaning of feminism may be unclear.

Feminism and sexism are generally two sides of the same coin. Feminism refers to the belief that women and men should have equal opportunities in economic, political, and social life, while sexism refers to a belief in traditional gender role stereotypes and in the inherent inequality between men and women.

In the United States, feminism as a social movement began during the abolitionist period preceding the Civil War, as such women as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, both active abolitionists, began to see similarities between slavery and the oppression of women. This new women’s movement focused on many issues but especially on the right to vote. As it quickly grew, critics charged that it would ruin the family and wreak havoc on society in other ways. They added that women were not smart enough to vote and should just concentrate on being good wives and mothers (Behling, 2001).

One of the most dramatic events in the women’s suffrage movement occurred in 1872, when Susan B. Anthony was arrested because she voted. At her trial a year later in Canandaigua, New York, the judge refused to let her say anything in her defense and ordered the jury to convict her. Anthony’s statement at sentencing won wide acclaim and ended with these words: “I shall earnestly and persistently continue to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, ‘Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God’” (Barry, 1988).

After women won the right to vote in 1920, the women’s movement became less active but began anew in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as women active in the Southern civil rights movement turned their attention to women’s rights, and it is still active today. To a profound degree, it has changed public thinking and social and economic institutions, but, as we will see coming up, much gender inequality remains. Because the women’s movement challenged strongly held traditional views about gender, it has prompted the same kind of controversy that its 19th-century predecessor did, resulting in a conservative backlash, echoing the concerns heard a century earlier (Faludi, 1991).

Several varieties of feminism exist. Although they all share the basic idea that women and men should be equal in their opportunities in all spheres of life, they differ in other ways (Lindsey, 2011). Liberal feminism believes that the equality of women can be achieved within our existing society by passing laws and reforming social, economic, and political institutions. In contrast, socialist feminism blames capitalism for women’s inequality and says that true gender equality can result only if fundamental changes in social institutions, and even a socialist revolution, are achieved. Radical feminism, on the other hand, says that patriarchy (male domination) lies at the root of women’s oppression and that women are oppressed even in non-capitalist societies. Patriarchy itself must be abolished, they say, if women are to become equal to men. Finally, an emerging multicultural feminism emphasizes that women of color are oppressed not only because of their gender but also because of their race and class (Andersen & Collins, 2010). They thus face a triple burden that goes beyond their gender. By focusing their attention on women of color in the United States and other nations, multicultural feminists remind us that the lives of these women differ in many ways from those of the middle-class women who historically have led U.S. feminist movements.

Correlates of Feminism

Because of the feminist movement’s importance, scholars have investigated why some people are more likely than others to support feminist beliefs. Their research uncovers several correlates of feminism (Dauphinais, Barkan, & Cohn, 1992). We have already seen one of these when we noted that religiosity is associated with support for traditional gender roles. To turn that around, lower levels of religiosity are associated with feminist beliefs and are thus a correlate of feminism.

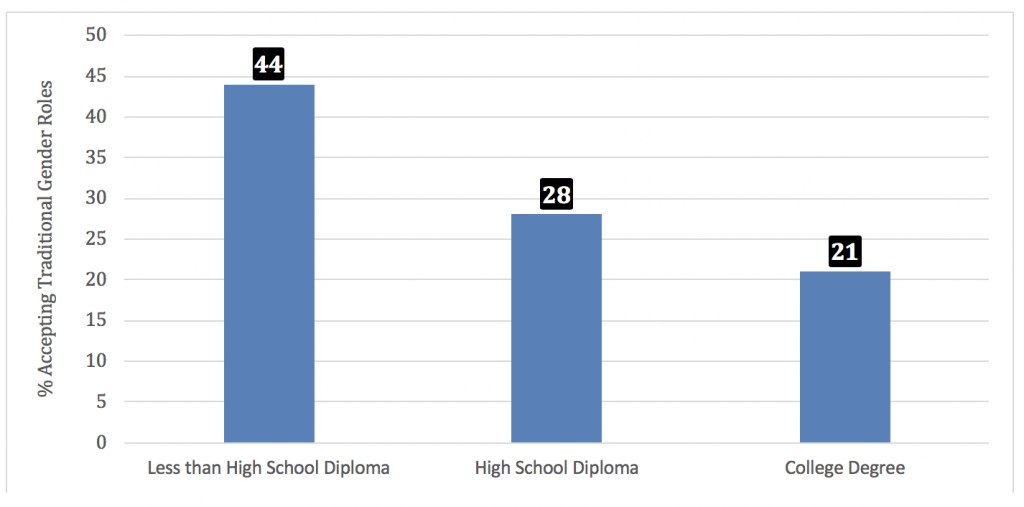

Several other such correlates exist. One of the strongest is education: the lower the education, the lower the support for feminist beliefs. Figure 11.5 “Education and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family” shows the strength of this correlation by using our familiar General Social Survey statement that men should achieve outside the home and women should take care of home and family. People without a high school degree are twice as likely as those with a college degree to agree with this statement.

Figure 11.5 Education and Acceptance of Traditional Gender Roles in the Family; Percentage agreeing that “it is better for a man to work and woman to stay home.”

Age is another correlate, as older people are more likely than younger people to believe in traditional gender roles. Again, looking at data from the General Social Survey, we find that while only 19% of people aged 18-34 accept traditional gender roles in the family, 42% of those over the age of 65 support traditional gender roles (2015).

11.3 Gender Inequality

While the women’s movement changed American life in many ways, gender inequality persists. Let’s look at examples of such inequality, much of it taking the form of institutional discrimination, which, as we saw in Chapter 6, can occur even if it is not intended to happen. We start with gender inequality in income and the workplace and then move on to a few other spheres of life.

Income and Workplace Inequality

In the last few decades, women have entered the workplace in increasing numbers, partly, and for many women mostly, out of economic necessity and partly out of desire for the sense of self-worth and other fulfillment that comes with work. This is true not only in the United States but also in many other nations. In 2016, 56.8% of U.S. women aged 16 or older were in the labor force, compared to only 43.3% in 1970; comparable figures for men were 69.2% in 2016 and 79.7% in 1970 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). Thus, while women’s labor force participation continues to lag behind men’s, they have narrowed the gap. The figures just cited include women of retirement age. When we just look at younger women, labor force participation is even higher. For example, 71.5% of women aged 35–44 were in the labor force in 2008, compared to only 46.8% in 1970 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017).

The Gender Gap in Income

Despite the gains women have made, problems persist. Perhaps the major problem is a gender gap in income. Women have earned less money than men ever since records started being kept (Reskin & Padavic, 2002). In the United States in the early 1800s, full-time women workers in agriculture and manufacturing earned less than 38% of what men earned. By 1885, they were earning about 50% of what men earned in manufacturing jobs. As the 1980s began, full-time women workers’ median weekly earnings were about 65% of men’s. Women have narrowed the gender gap in earnings since then: their weekly earnings in 2016 are 82% of men’s among full-time workers (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). Still, this means that for every $10,000 men earn, women earn only about $8,200. For the average worker, this gap amounts to roughly $500,000 over a lifetime of working.

As Table 11.1 “Median Annual Earnings of Full-Time, Year-Round Workers Aged 25–64 by Educational Attainment, 2015” shows, this gender gap exists for all levels of education. On the average, women with a bachelor’s degree or higher and working full time earn more than $20,000 less per year than their male counterparts.

Table 11.1 Median Annual Earnings of Full-Time, Year-Round Workers Aged 25–64 by Educational Attainment, 2015

|

|

Less than high school completion |

High School Degree |

Some college, no degree |

Associate’s degree |

Bachelor’s degree |

Master’s degree or higher |

|

Men |

$26,210 |

$33,980 |

$38,960 |

$42,850 |

$54,960

|

$69,530 |

|

Women |

$19,970 |

$27,000 |

$29,990 |

$31,630 |

$44,780

|

$57,590 |

|

$ Differences |

$6,240 |

$6,980 |

$8,970 |

$11,220 |

$10,180

|

$11,940 |

|

Gender Gap (women ÷ men) |

76.2% |

79.6% |

77.0% |

73.8% |

81.5% |

82.8% |

Source: Data from National Center for Education Statistics (2016). Digest of Educational Statistics, 2016. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d16/tables/dt16_502.30.asp

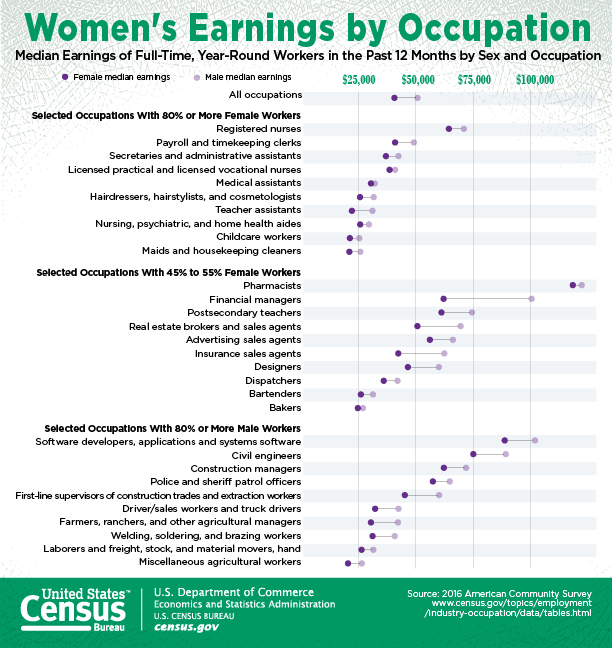

What accounts for the gender gap in earnings? A major reason is sex segregation in the workplace, which accounts for up to 45% of the gender gap (Reskin & Padavic 2002). Although women have increased their labor force participation, the workplace remains segregated by gender. Almost half of all women work in a few low paying clerical and service (e.g., waitressing) jobs, while men work in a much greater variety of jobs, including high-paying ones. Table 11.2 “Gender Segregation in the Workplace for Selected Occupations, 2017” shows that many jobs are composed primarily of women or of men. Part of the reason for this segregation is that socialization affects what jobs young men and women choose to pursue, and part of the reason is that women and men do not want to encounter difficulties they may experience if they took a job traditionally assigned to the other sex. A third reason is that sex-segregated jobs discriminate against applicants who are not the “right” sex for that job. Employers may either consciously refuse to hire someone who is the “wrong” sex for the job or have job requirements (e.g., height requirements) and workplace rules (e.g., working at night) that unintentionally make it more difficult for women to qualify for certain jobs. Although such practices and requirements are now illegal, they still continue. The sex segregation they help create contributes to the continuing gender gap between female and male workers. Occupations dominated by women tend to have lower wages and salaries. Because women are concentrated in low-paying jobs, their earnings are much lower than men’s (Reskin & Padavic, 2002).

Table 11.2 Gender Segregation in the Workplace for Selected Occupations, 2017

|

Occupation |

% Female Workers |

% Male Workers |

|

Speech-language pathologists |

98.0 |

2.0 |

|

Preschool and Kindergarten teachers |

97.7 |

2.3 |

|

Secretaries and Administrative Assistants |

95.0 |

5.0 |

|

Dental Hygienists |

94.9 |

5.1 |

|

Receptionists |

91.0 |

9.0 |

|

Registered nurses |

89.9 |

10.1 |

|

Social Workers |

82.5 |

17.5 |

|

Food servers (waiters/waitresses) |

69.9 |

30.1 |

|

Physicians |

40.0 |

60.0 |

|

Lawyers |

37.4 |

62.6 |

|

Dentists |

35.8 |

74.2 |

|

Architects |

28.6 |

71.4 |

|

Chief Executives |

28.0 |

72.0 |

|

Computer software engineers |

18.7 |

81.3 |

|

Police and Sheriff’s Patrol Officers |

13.6 |

86.4 |

|

Mechanical Engineers |

9.2 |

90.8 |

|

Carpenters |

2.2 |

97.8 |

|

Electricians |

2.5 |

97.5 |

Source: Data from “Employed Persons by Detailed Occupation, Sex, Race, and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 19 Jan. 2018. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

This fact raises an important question: why do women’s jobs pay less than men’s jobs? Is it because their jobs are not important and require few skills (recalling the functional theory of stratification discussed in Chapter 5 “Groups and Organizations”)? The evidence indicates otherwise: women’s work is devalued precisely because it is women’s work, and women’s jobs thus pay less than men’s jobs because they are women’s jobs (Magnusson, 2009).

Studies of comparable worth support this argument (Stone & Kuperberg, 2005; Wolford, 2005). Researchers rate various jobs in terms of their requirements and attributes that logically should affect the salaries they offer: the importance of the job, the degree of skill it requires, the level of responsibility it requires, the degree to which the employee must exercise independent judgment, and so forth. They then use these dimensions to determine what salary a job should offer. Some jobs might be “better” on some dimensions and “worse” on others but still end up with the same predicted if everything evens out.

When researchers make their calculations, they find that certain women’s jobs pay less than men’s even though their comparable worth is equal to or even higher than the men’s jobs. For example, a social worker may earn less money than a probation officer, even though calculations based on comparable worth would predict that a social worker should earn at least as much. The comparable worth research demonstrates that women’s jobs pay less than men’s jobs of comparable worth and that the average working family would earn several thousand dollars more annually if pay scales were reevaluated based on comparable worth and women were paid more for their work.

Even when women and men work in the same jobs, women often earn less than men (Sherrill, 2009), and men are more likely than women to hold leadership positions in these occupations. Census data provide ready evidence of the lower incomes women receive even in the same occupations. For example, female marketing and sales managers earn only 68% of what their male counterparts earn; female financial managers earn only 65.2% of what their male counterparts earn; female sales workers earn only 66.8%; female physical scientists earn only 66.1%; female doctors earn only 80.1%; and even female maids and housekeepers, who are almost 90% of workers in this category, earn only 85.7% of their male counterparts (U.S. Department of Labor, 2017). When variables like number of years on the job, number of hours worked per week, and size of firm are taken into account, these disparities diminish but do not disappear altogether, and it is very likely that sex discrimination (conscious or unconscious) by employers accounts for much of the remaining disparity. There are a few exceptions including fashion modeling, pornography, and stripping, where women make more than their male counterparts (Mears and Connell 2016).

Litigation has suggested or revealed specific instances of sex discrimination in earnings and employment. In July 2009, the Dell computer company, without admitting any wrongdoing, agreed to pay $9.1 million to settle a class action lawsuit, brought by former executives that alleged sex discrimination in salaries and promotions (Walsh, 2009). Earlier in the decade, a Florida jury found Outback Steakhouse liable for paying a woman site development assistant only half what it paid a man with the same title. After she trained him, Outback assigned him most of her duties, and when she complained, Outback transferred her to a clerical position. The jury awarded her $2.2 million in compensatory and punitive damages (U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, 2001). More recently, in 2017 and 2018, numerous lawsuits have been filed against companies such as Nike, Google, Spotify and the Detroit Free Press, alleging violations of equal-pay laws.

Some of the sex discrimination in employment reflects the existence of two related phenomena, the glass ceiling and the glass escalator. Women may be promoted in a job only to find they reach an invisible “glass ceiling” beyond which they cannot get promoted, or they may not get promoted in the first place. In the largest U.S. corporations, women constitute only about 28% of chief executives, and women executives are paid much less than their male counterparts (Jenner & Ferguson, 2009). Although these disparities stem partly from the fact that women joined the corporate ranks much more recently than men, they also reflect a glass ceiling in the corporate world that prevents qualified women from rising up above a certain level (Hymowitz, 2009). Men, on the other hand, can often ride a “glass escalator” to the top, even in female occupations. An example is seen in K-12 education, where principals typically rise from the ranks of teachers. Although men constitute only about 24% of all public school teachers, they account for about 48% of all school principals and more than 75% of school superintendents (Superville, 2018).

Lastly, researchers find that there is a difference in behavior associated with negotiating salaries and raises between women and men. Women are less likely to negotiate aggressively for higher salaries and raises, and when they do, they are more likely to be perceived negatively by their supervisors (U.S. Department of Labor, 2017). Compounding this, when people change jobs, new employers often use past salaries of a new employee to determine the salary offer they make.

Whatever the reasons for the gender gap in income, the fact that women make so much less than men means that female-headed families are especially likely to be poor. In 2014, about 31% of these families lived in poverty, compared to only 6% of married-couple families (U.C. Davis Center for Poverty Research, 2014). The term feminization of poverty refers to the fact that female-headed households are especially likely to be poor. The gendering of poverty in this manner is one of the most significant manifestations of gender inequality in the United States.

Sexual Harassment

Another problem in workplaces and schools is sexual harassment, which, as defined by federal guidelines and legal rulings and statutes, consists of unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or physical conduct of a sexual nature used as a condition of employment or promotion or that interferes with an individual’s job performance and creates an intimidating or hostile environment.

Although men can be, and are, sexually harassed, women are more often the targets of sexual harassment, which is often considered a form of violence against women. This gender difference exists for at least two reasons, one cultural and one structural. The cultural reason centers on the depiction of women and the socialization of men. As our discussion of the mass media and gender socialization indicated, women are still depicted in our culture as sexual objects that exist for men’s pleasure. At the same time, our culture socializes men to be sexually assertive. These two cultural beliefs combine to make men believe that they have the right to make verbal and physical advances to women in the workplace. When these advances fall into the guidelines listed here, they become sexual harassment.

The second reason that most targets of sexual harassment are women is more structural. Reflecting the gendered nature of the workplace and of the educational system, typically the men doing the harassment are in a position of power over the women they harass. A male boss harasses a female employee, or a male professor harasses a female student or employee. These men realize that subordinate women may find it difficult to resist their advances for fear of reprisals: a female employee may be fired or not promoted, and a female student may receive a bad grade.

How common is sexual harassment? This is difficult to determine, as the men who do the sexual harassment typically don’t profess their guilt, and the women who suffer it often keep quiet because of the repercussions just listed. But anonymous surveys of women employees in corporate and other settings commonly find that 40%–65% of respondents report being sexually harassed (Rospenda, Richman, & Shannon, 2009).

Sexual harassment cases continue to make headlines. In recent years, accusations, arrests and trials related to sexual harassment, misconduct, assault and rape associated with abuse committed by numerous high-profile male political leaders, judges, media figures, musicians, athletes and corporate leaders, has resulted in a growing recognition of the pervasiveness of such inequalities. Additionally, reaction to these high-profile cases has helped to fuel the anti-sexual harassment “Me Too” social movement.

Women of Color: A Triple Burden

Earlier we mentioned multicultural feminism, which stresses that women of color face difficulties for three reasons: their gender, their race, and, often, their social class, which is more frequently near the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. They thus face a triple burden that manifests itself in many ways.

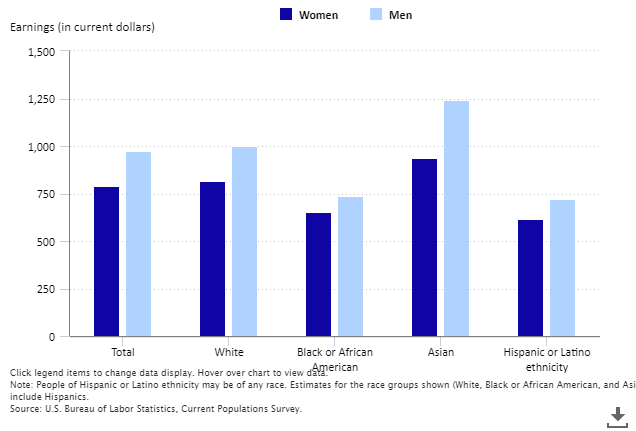

For example, BIPOC women experience “extra” income inequality. Earlier we discussed the gender gap in earnings, with women earning 82% of what men earn, but women of color face both a gender gap and a racial/ethnic gap. Figure 11.6 “Median Usual Weekly Earnings of Women and Men Who Are Full-Time Wage and Salary Workers, by Race and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity” depicts this double gap for full-time workers. Women of all racial-ethnic groups, when compared to men from the same group, earn between 87% to 92% of their male counterparts. The minority status of these women compounds to produce an especially high gap between Black and Latina women and white men: Black women earn only 65.3% and Latina women earn only 61.6% of what white men earn.

Figure 11.6 Median Usual Weekly Earnings of Women and Men Who Are Full-Time Wage and Salary Workers, by Race and Hispanic or Latino Ethnicity

These differences in income mean that Black and Latina women are poorer than white women. We noted earlier that about 31% of all female-headed families are poor. This figure masks race/ ethnic differences among such families: 21.5% of families headed by non-Latina white women are poor, compared to 40.5% of families headed by Black women and also 40.5% of families headed by Latina women (Denavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2010). While white women are poorer than white men, Black and Latina women are clearly poorer than white women.

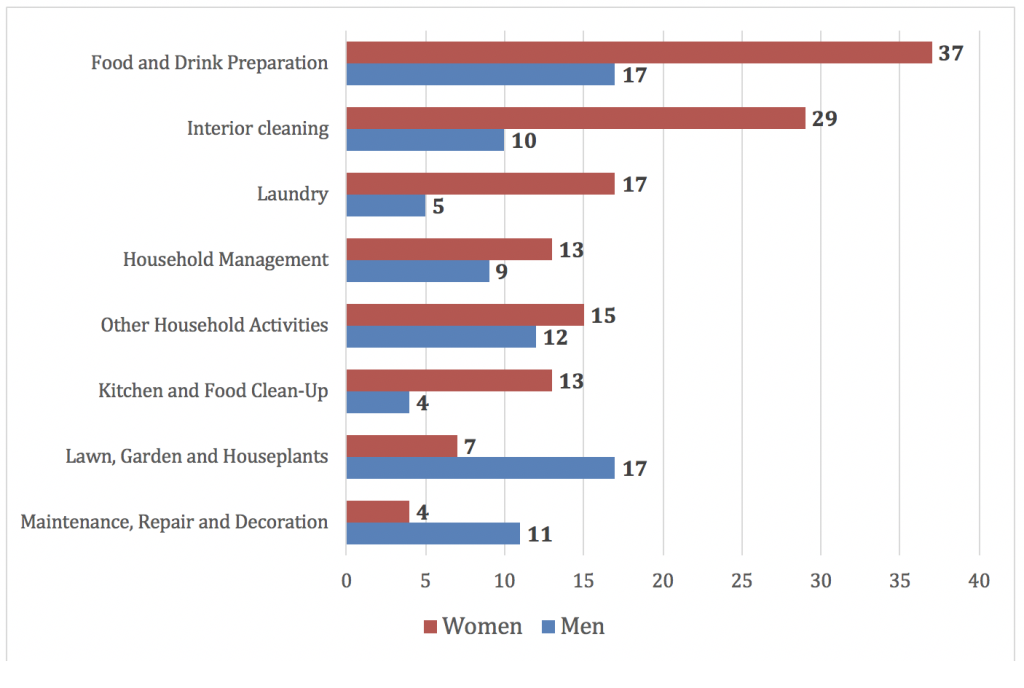

Household Inequality

We will talk more about the family in in Chapter 12: Marriage and Families, but for now the discussion will center on housework. Someone has to do housework, and that someone is more often a woman. It takes many hours a week to clean the bathrooms, cook, shop in the grocery store, vacuum, and do everything else that needs to be done. In the 2015 American Time Use Survey, it was found that during an average day, women spend 2 hours and 15 minutes on household activities, while men spend 1 hours and 25 minutes, as demonstrated in Figure 11.7 “Average Minutes Per Day Spent on Household Activities.” Over a week’s time, this equates to women spending nearly 16 hours on household related tasks, compared to 10 hours or so spent by men on equivalent tasks.

Figure 11.7 Average Minutes Per Day Spent on Household Activities

The disparity discussed above holds true even when women work full-time outside the home. Leading sociologist, Arlie Hochschild, observed in a widely cited book that women engage in a “second shift” of unpaid work when they come home from their paying job (1989).

The good news is that gender differences in housework time are smaller than a generation ago. The bad news is that a large gender difference remains, thus, in the realm of household work, then, gender inequality persists.

11.4 Violence Against Women: Rape and Pornography

When we consider interpersonal violence of all kinds—homicide, assault, robbery, and rape and sexual assault—men are more likely than women to be victims of violence. While true, this fact obscures another fact: men and women are equally likely to be violent and to experience violence in relationships, but women are significantly more likely than men to be hospitalized and killed by their male partners. They are also much more likely to be portrayed as victims of pornographic violence on the Internet and in videos, magazines, and other outlets. Finally, women are more likely than men to be victims of domestic violence, or violence between spouses and others with intimate relationships. The gendered nature of these acts against women distinguishes them from the violence men suffer. Violence is directed against men not because they are men per se, but because of anger, jealousy, and the sociological reasons discussed earlier in the review of deviance and crime. But rape and sexual assault, domestic violence, and pornographic portrayals of violence are directed against women precisely because they are women. These acts are thus an extreme extension of the gender inequality women face in other areas of life.

Rape

Susan Griffin (1971, p. 26) began a classic essay on rape in 1971 with this startling statement:

I have never been free of the fear of rape. From a very early age I, like most women, have thought of rape as a part of my natural environment—something to be feared and prayed against like fire or lightning. I never asked why men raped; I simply thought it one of the many mysteries of human nature.

What do we know about rape? Why do men rape? Our knowledge about the extent and nature of rape and reasons for it comes from three sources: the FBI Uniform Crime Reports and the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), and surveys of and interviews with women and men conducted by academic researchers. From these sources we have a fairly good idea of how much rape occurs, the context in which it occurs, and the reasons for it. What do we know?

The Extent and Context of Rape

According to the National Crime Victimization Survey, 298,410 incidences of rape or sexual assault occurred in the United States in 2016 (Morgan & Kena, 2018). Other research indicates that up to one-third of U.S. women will experience a rape or sexual assault, including attempts, at least once in their lives (Barkan, 2012). A study of a random sample of 420 Toronto women involving intensive interviews yielded even higher figures: 56% said they had experienced at least one rape or attempted rape, and two-thirds said they had experienced at least one rape or sexual assault, including attempts. The researchers, Melanie Randall and Lori Haskell (1995, p. 22), concluded that “it is more common than not for a woman to have an experience of sexual assault during their lifetime.”

These figures apply not just to the general public but also to college students. In a report released in 2016 by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, for which 15,000 women and 8,000 men at 9 institutions of higher education were surveyed, 21% of female and 7% of male undergraduates stated they were sexually assaulted or raped while in college. Of the women who said they were raped, only 12.5% reported the crime to law enforcement of college officials (Inside Higher Ed, 2016). Thus, at a campus of 10,000 students of whom 5,000 are women, about 1,050 will be raped or sexually assaulted over a period of 4 years.

The public image of rape is of the proverbial stranger attacking a woman in an alleyway. While such rapes do occur, most rapes actually happen between people who know each other. A wide body of research finds that 60%–80% of all rapes and sexual assaults are committed by someone the woman knows, including husbands, ex-husbands, boyfriends, and ex-boyfriends, and only 20%–35% by strangers (Barkan, 2012). A woman is thus 2 to 4 times more likely to be raped by someone she knows than by a stranger.

Explaining Rape

Sociological explanations of rape fall into cultural and structural categories similar to those presented earlier for sexual harassment. Various “rape myths” in our culture support the absurd notion that women somehow enjoy being raped, want to be raped, or are “asking for it” (Franiuk, Seefelt, & Vandello, 2008). A related cultural belief is that women somehow ask or deserve to be raped by the way they dress or behave. A third cultural belief is that a man who is sexually active with a lot of women has a higher status. A man with multiple sex partners continues to be the source of envy among many of his peers. At a minimum, men are still the ones who have to “make the first move” and then continue making more moves. There is a thin line between being sexually assertive and sexually aggressive (Kassing, Beesley, & Frey, 2005).

These three cultural beliefs—that women enjoy being forced to have sex, that they ask or deserve to be raped, and that men should be sexually assertive or even aggressive—combine to produce a cultural recipe for rape. Although most men do not rape, the cultural beliefs and myths just described help account for the rapes that do occur. Recognizing this, the contemporary women’s movement began attacking these myths back in the 1970s, and the public is much more conscious of the true nature of rape than a generation ago. That said, much of the public still accepts these cultural beliefs and myths, and prosecutors continue to find it difficult to win jury convictions in rape trials unless the woman who was raped had suffered visible injuries, had not known the man who raped her, and/or was not dressed attractively (Levine, 2006).

Structural explanations for rape emphasize the power differences between women and men similar to those outlined earlier for sexual harassment. In societies that are male dominated, rape and other violence against women is a likely outcome, as they allow men to demonstrate and maintain their power over women. Supporting this view, studies of preindustrial societies and of the 50 states of the United States find that rape is more common in societies where women have less economic and political power (Baron & Straus, 1989; Sanday, 1981). Poverty is also a predictor of rape: although rape in the United States transcends social class boundaries, it does seem more common among poorer segments of the population than among wealthier segments, as is true for other types of violence (Rand, 2009). Scholars think the higher rape rates among the poor stem from poor men trying to prove their “masculinity” by taking out their economic frustration on women (Martin, Vieraitis, & Britto, 2006).

Reducing Rape

In sum, a sociological perspective tells us that cultural myths and economic and gender inequality help lead to rape, and that the rape problem goes far beyond a few psychopathic men who rape women. A sociological perspective thus tells us that our society cannot just stop at doing something about these men. Instead it must make more far-reaching changes by changing people’s beliefs about rape and by making every effort to reduce poverty and to empower women.

Aside from this fundamental change, other remedies, such as additional and better funded rape-crisis centers, would help people who experience rape and sexual assault. Yet even here women of color face an additional barrier. Because the anti-rape movement was begun by white, middle-class feminists, the rape-crisis centers they founded tended to be near where they live, such as college campuses, and not in the areas where women of color live, such as inner cities and Native American reservations. This meant that women of color who experienced sexual violence lacked the kinds of help available to their white, middle-class counterparts (Matthews, 1989), and, despite some progress, this is still true today.

Pornography

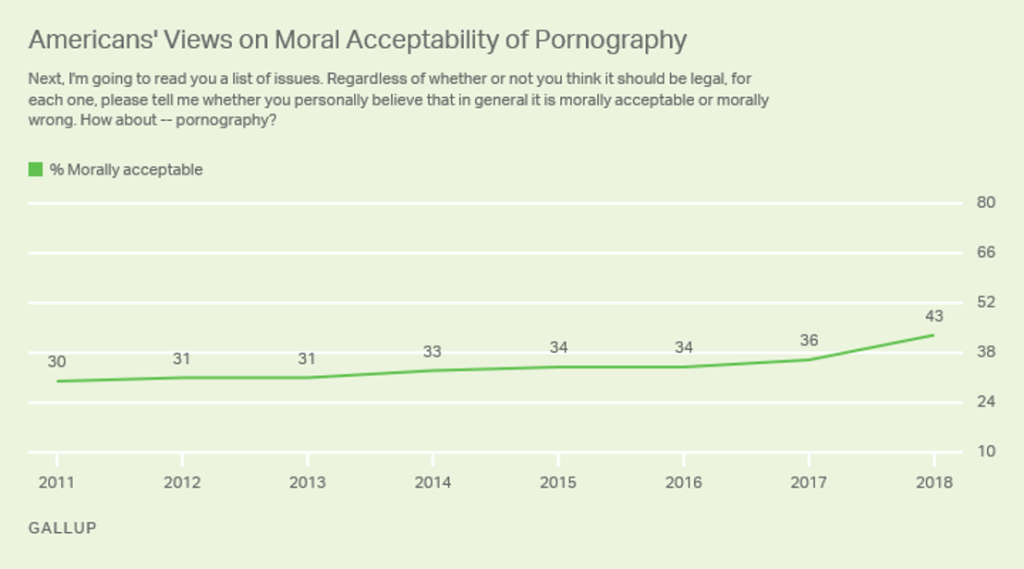

Back in the 1950s, young boys in the United States would page through National Geographic magazine to peek at photos of partially nude women. Those photos, of course, were not put there to excite boys across the country; instead they were there simply to depict native people in their natural habitat. Another magazine began about the same time that also contained photos of nude women. Its name was Playboy, and its photos obviously had a much different purpose: to excite viewers of the magazine. More graphic magazines followed, and today mainstream media and the internet show more nudity and sex than could easily be found in the days of National Geographic. In fact, 43.5% of men participating in a recent study indicated they were first exposed to pornography accidentally (Sliwa 2017).

There is opposition to pornography, but two very different groups have been especially outspoken over the years. One of these groups, religious moralists, condemn pornography as a violation of religious values and as an offense to society’s moral order. On the other side, some feminist groups oppose pornography for its sexual objectification of women and especially condemn the kind of pornography that glorifies sexual violence against women. Some feminists also charge that pornography promotes rape by reinforcing the cultural myths discussed earlier. As one writer put it in a famous phrase some 40 years ago, “Pornography is the theory, and rape the practice” (Morgan, 1980, p. 139).

This charge raises an important question: to what extent does pornography cause rape or other violence against women? The fairest answer might be that we do not really know. Several studies do conclude that violent pornography makes rape more likely. For example, male students who watch violent pornography in experiments later exhibit more hostile attitudes toward women than those watching consensual sex or nonsexual interaction. However, it remains unclear whether viewing pornography has a longer-term effect that lasts beyond the laboratory setting, and scholars and other observers continue to disagree over pornography’s effects on the rape rate (Ferguson & Hartley, 2009). Psychological research conducted at a large Midwestern University found “the younger a man was when he first viewed pornography, the more likely he was to want power over women (Sliwa 2017).” Even if there is a causal relationship between pornography and rape, how would that be addressed without censorship? And what of the other more statistically linked causes, such as alcohol use and substance abuse? In a free society, civil liberties advocates say, we must proceed very cautiously. Once we ban some forms of pornography, they ask, where do we stop (Strossen, 2000)?

11.5 The Benefits and Costs of Being Male

Most of the discussion so far has been about women, and with good reason: in a sexist society such as our own, women are the subordinate, unequal sex. But gender means more than female, and a few comments about men are in order.

Benefits

Many scholars talk about male privilege, or the advantages that males automatically have in a patriarchal society whether or not they realize they have these advantages (McIntosh, 2007). A few examples illustrate male privilege. Men can usually walk anywhere they want or go into any bar they want without having to worry about being raped or sexually harassed. Susan Griffin was able to write “I have never been free of the fear of rape” because she was a woman: it is no exaggeration to say that few men could write the same thing and mean it. Although some men are sexually harassed, most men can work at any job they want without having to worry about sexual harassment. Men can walk down the street without having strangers make crude remarks about their looks, dress, and sexual behavior. Men can apply for most jobs without worrying about being rejected or, if hired, not being promoted because of their gender. We could go on with many other examples, but the fact remains that in a patriarchal society, men automatically have advantages just because they are men, even if race, social class, and sexual orientation affect the degree to which they are able to enjoy these advantages.

Costs

Yet it is also true that men pay a price for living in a patriarchy. Without trying to claim that men have it as bad as women, scholars are increasingly pointing to the problems men face in a society that promotes male domination and traditional standards of masculinity such as assertiveness, competitiveness, and toughness (Kimmel & Messner, 2010). Socialization into masculinity is thought to underlie many of the emotional problems men experience, which stem from a combination of their emotional inexpressiveness and reluctance to admit to, and seek help for, various personal problems (Wong & Rochlen, 2005). Sometimes these emotional problems build up and explode, as mass shootings by males at schools and elsewhere indicate, or express themselves in other ways. Compared to girls, for example, boys are much more likely to be diagnosed with emotional disorders, learning disabilities, and attention deficit disorder, and they are also more likely to commit suicide and to drop out of high school.

Men experience other problems that put themselves at a disadvantage compared to women. They commit much more violence than women do and, apart from rape, also suffer a much higher rate of violent victimization. They die earlier than women and are injured more often. Because men are less involved than women in child-rearing, they also miss out on the joy of parenting that women are much more likely to experience.

Growing recognition of the problems males experience because of their socialization into masculinity has led to increased concern over what is happening to American boys. Citing the strong linkage between masculinity and violence, some writers urge parents to raise their sons differently in order to help our society reduce its violent behavior (Miedzian, 2002). In all of these respects, boys and men—and our nation as a whole—are paying a very real price for being male in a patriarchal society.

Reducing Gender Inequality

Gender inequality is found in varying degrees in most societies around the world, and the United States is no exception. Just as racial/ethnic stereotyping and prejudice underlie racial/ethnic inequality, so do stereotypes and false beliefs underlie gender inequality. Although these stereotypes and beliefs have weakened considerably since the 1970s thanks in large part to the contemporary women’s movement and the LGBTQIA rights movements, they obviously persist and hamper efforts to achieve full gender equality.

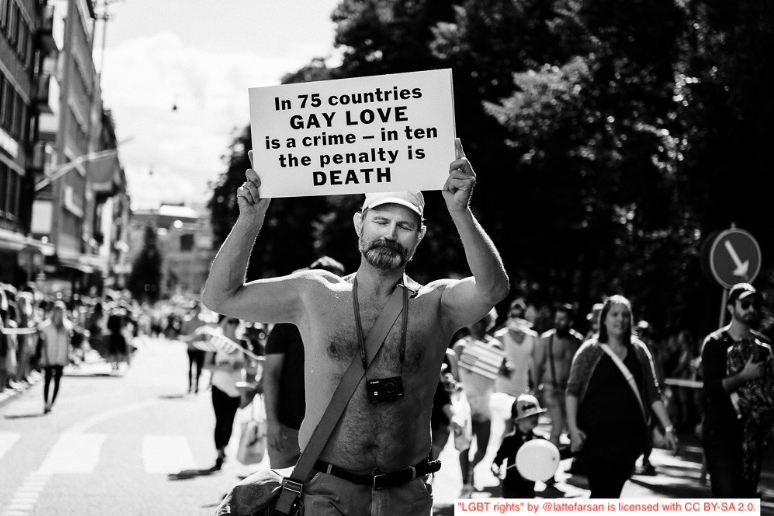

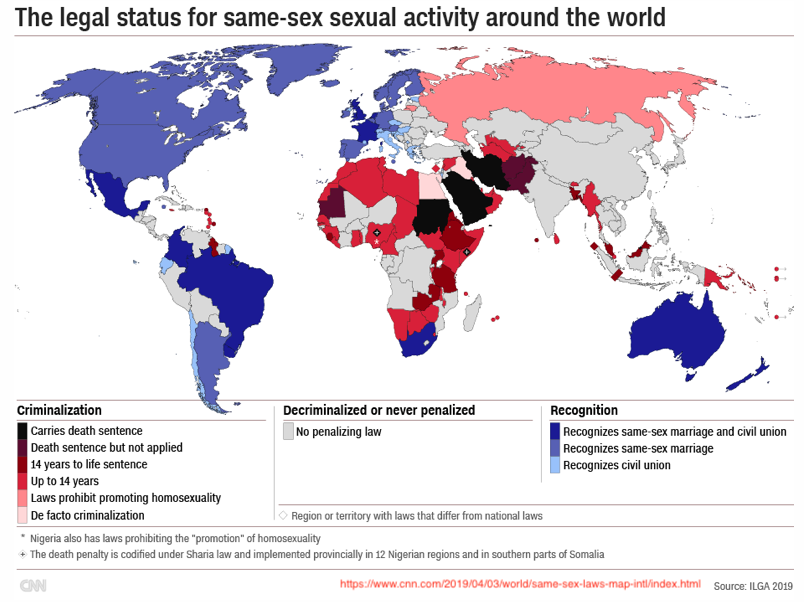

A sociological perspective reminds us that gender inequality stems from a complex mixture of cultural and structural factors that must be addressed if gender inequality is to be reduced further than it already has been since the 1970s. Despite changes during this period, children are still socialized from birth into traditional notions of femininity and masculinity, and gender-based stereotyping incorporating these notions still continues. Although people should generally be free to pursue whatever family and career responsibilities they desire, socialization and stereotyping still combine to limit the ability of girls and boys and women and men alike to imagine less traditional possibilities. Meanwhile, structural obstacles in the workplace and elsewhere continue to keep women in a subordinate social and economic status relative to men. Cultural and structural factors also continue to produce inequality based on sexual orientation, an inequality that is reinforced both by the presence of certain laws directed at gays and lesbians and by the absence of other laws prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation (such as laws prohibiting employment discrimination).

To reduce gender inequality, then, a sociological perspective suggests various policies and measures to address the cultural and structural factors that help produce gender inequality. These might include, but are not limited to, the following:

1. Reduce socialization by parents and other adults of girls and boys into traditional gender roles.

2. Confront gender stereotyping and sexual orientation stereotyping by the popular and news media.

3. Increase public consciousness of the reasons for, extent of, and consequences of rape and sexual assault, sexual harassment, and pornography.

4. Increase enforcement of existing laws against gender-based employment discrimination and against sexual harassment.

5. Increase funding of rape-crisis centers and other services for girls and women who have been raped and/or sexually assaulted.

6. Increase government funding of high-quality day-care options to enable parents, and especially mothers, to work outside the home if they so desire, and to do so without fear that their finances or their children’s well-being will be compromised.

7. Pass federal and state legislation banning employment and housing discrimination based on sexual orientation and transgender identity and expression.

8. Increase mentorship and other efforts to boost the number of women in traditionally male occupations and in positions of political leadership.

11.6 Sex and Sexuality

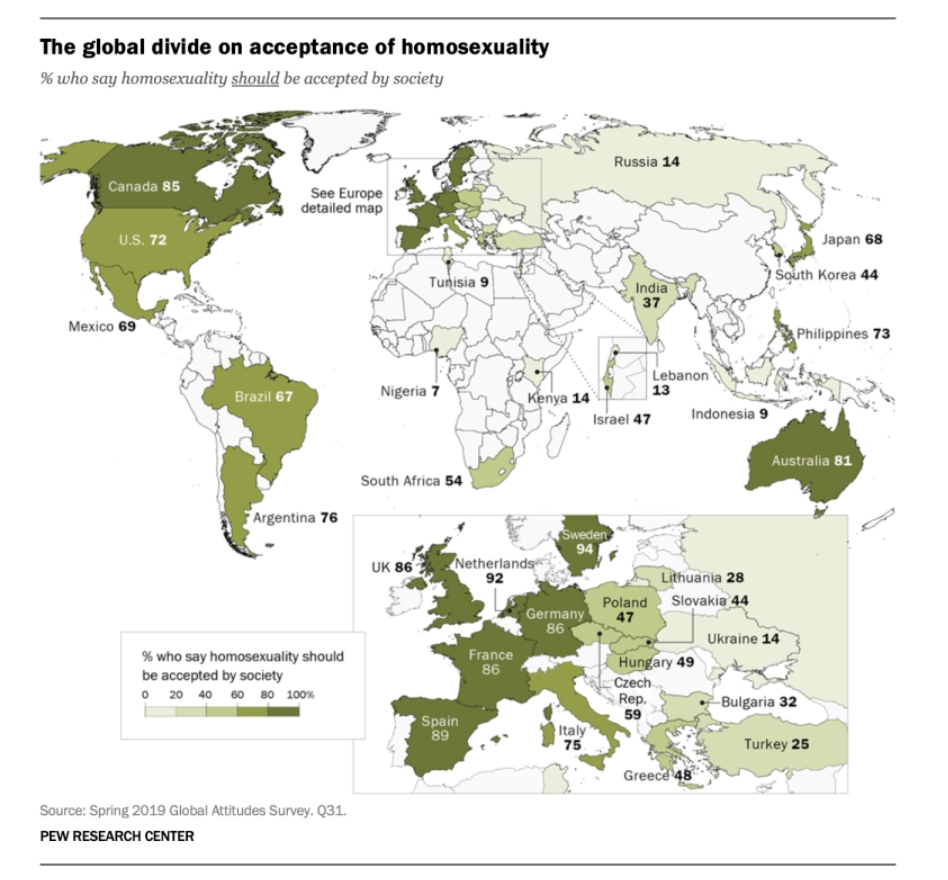

Sexual Orientation and Inequality