14

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Explain why compulsory education arose in the 19th century and discuss the relationship between formal education and national culture, economic conditions and social location.

- Define education and compare and contrast how the purpose, process and outcomes of the educational institution are discussed within each of the theoretical perspectives.

- Outline and critique the problems and proposed solutions associated with the U.S. educational system.

- Define religion, distinguish between sacred and profane aspects of society and outline aspects of culture associated with religion.

- Compare and contrast the functionalist and conflict perspectives on religion and discuss Weber’s theory on the relationship between religion and social change.

- Explain how the forms of religion have changed historically, outline and provide examples of the different types of religious groups, and discuss the geographic distribution of current major world religions.

- Summarize the main features of religion in the U.S., including issues related to segregation, pluralism and secularization.

Education is the social institution through which a society teaches its members the skills, knowledge, norms, and values they need to learn to become good, productive members of their society. As this definition makes clear, education is an important part of socialization. Education is both formal and informal. Formal education is often referred to as schooling, and as this term implies, it occurs in schools under teachers, principals, and other specially trained professionals. Informal education may occur almost anywhere, but for young children it has traditionally occurred primarily in the home, with their parents as their instructors. Day care has become an increasingly popular venue in industrial societies for young children’s instruction, and education from the early years of life is thus more formal than it used to be.

Education in early America was hardly formal. During the colonial period, the Puritans in what is now Massachusetts required parents to teach their children to read and also required larger towns to have an elementary school, where children learned reading, writing, and religion. In general, though, schooling was not required in the colonies, and only about 10% of colonial children, usually just the wealthiest, went to school (Urban, Jennings, & Wagoner, 2008).

To help unify the nation after the Revolutionary War, textbooks were written to standardize spelling and pronunciation and to instill patriotism and religious beliefs in students. At the same time, these textbooks included negative stereotypes of Native Americans and certain immigrant groups. The children going to school continued primarily to be those from wealthy families. By the mid-1800s, a call for free, compulsory education had begun, and compulsory education became widespread by the end of the century. This was an important development, as children from all social classes could now receive a free, formal education. Compulsory education was intended to further national unity and to assimilate immigrants by teaching them “American” values. It also arose because of industrialization, as an industrial economy demanded reading, writing, and math skills much more than an agricultural economy had.

Free, compulsory education, of course, applied only to primary and secondary schools. Until the mid-1900s, very few people went to college, and those who did typically came from the wealthy families. After World War II, due in large part to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (also known as the G.I. Bill) which offered stipends to military veterans to cover expenses related to college, enrollments soared, and today more people are attending college than ever before.

At least two themes emerge from this brief history. One is that until very recently, formal schooling was restricted to wealthy males. This means that males who were not white and rich were excluded from formal schooling, as were virtually all females, whose education took place informally at home. Today, as we will see, race, ethnicity, social class, and gender continue to affect both educational achievement and the amount of learning occurring in schools.

Second, although the rise of free, compulsory education was an important development, the reasons for this development trouble some critics (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Cole, 2008). Because compulsory schooling began in part to prevent immigrants’ values from corrupting “American” values, they see its origins as smacking of ethnocentrism. They also criticize its intention to teach workers the skills they needed for the new industrial economy. Because most workers were very poor in this economy, these critics say, compulsory education served the interests of the upper class much more than it served the interests of workers. Whose interests are served by education remains an important question addressed by sociological perspectives on education, to which we now turn.

14.2 Sociological Perspectives on Education

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009). Table 14.1 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what these approaches say.

Table 14.1 Theory Snapshot

|

Theory |

Major Assumptions |

|

Functionalism |

Education serves several functions for society. These include (a) socialization, (b) social integration, (c) social placement, and (d) social and cultural innovation. Latent functions include child care, the establishment of peer relationships, and lowering unemployment by keeping high school students out of the full-time labor force. |

|

Conflict Perspective |

Education promotes social inequality through the use of tracking and standardized testing and the impact of its “hidden curriculum.” Schools differ widely in their funding and learning conditions, and this type of inequality leads to learning disparities that reinforce social inequality. |

|

Symbolic Interactionism |

This perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. Research finds that social interaction in schools affects the development of gender roles and that teachers’ expectations of pupils’ intellectual abilities affect how much pupils learn. |

The Functions of Education

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization. If children need to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach academic content, as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism, punctuality, individualism and competition. Regarding individualism and competition, American students from an early age compete as individuals over grades and other rewards. The situation is quite the opposite in Japan, where children learn the traditional Japanese values of harmony and group belonging from their schooling (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). They learn to value their membership in their homeroom, or kumi, and are evaluated more on their kumi’s performance than on their own individual performance.

A second function of education is social integration. For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the 19th century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, U.S. history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life. Such integration is a major goal of the English-only movement, whose advocates say that only English should be used to teach children whose native tongue is Spanish, Vietnamese, or whatever other language their parents speak at home. Critics of this movement say it slows down these children’s education and weakens their ethnic identity (Schildkraut, 2005).

A third function of education is social placement. Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way they are prepared in the most appropriate way possible for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking shortly.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

Figure 14.1 The Functions of Education

Education also involves several latent functions, functions that are by-products of going to school and receiving an education rather than a direct effect of the education itself. One of these is child care. Once a child starts kindergarten and then first grade, for several hours a day the child is taken care of outside of the home. The establishment of peer relationships is another latent function of schooling. Most of us met many of our friends while we were in school at whatever grade level, and some of those friendships endure the rest of our lives. A final latent function of education is that it keeps millions of high school students out of the full-time labor force. This fact keeps the unemployment rate lower than it would be if they were in the labor force.

Education and Inequality

Conflict theory does not dispute most of the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant and talks about various ways in which education perpetuates social inequality (Hill, Macrine, & Gabbard, 2010; Liston, 1990). One example involves the function of social placement. As most schools track their students starting in grade school, the students thought to be more capable, according to standardized tests, are placed in the higher tracks (especially in reading and math), while students thought to be less capable are placed in lower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

While tracking is seen by some as beneficial for providing educational programming based on level of ability, conflict theorists say tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into different tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: white, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class, race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2006; Oakes, 2005).

Social inequality is also perpetuated through the widespread use of standardized tests. Critics say these tests continue to be culturally biased, as they include questions whose answers are most likely to be known by white, middle-class students, whose backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer the questions. They also say that scores on standardized tests reflect students’ socioeconomic status and experiences in addition to their academic abilities. To the extent this critique is true, standardized tests perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008).

As we will see, schools in the United States also differ mightily in their resources, learning conditions, and other aspects, all of which affect how much students can learn in them. Simply put, schools are unequal, and their very inequality helps perpetuate inequality in the larger society. Conflict theorists also say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculum, by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008). Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

Symbolic Interactionism and School Behavior

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993).

Another body of research shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with them, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less capable, they tend to spend less time with them and act in a way that leads the students to learn less. One of the first studies to find this example of a self-fulfilling prophecy was conducted by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968). They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They tested the students again at the end of the school year; not surprisingly the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. To the extent this type of self-fulfilling prophecy occurs, it helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Other research focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Several studies from the 1970s through the 1990s found that teachers call on boys more often and praise them more often (American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, 1998; Jones & Dindia, 2004). Teachers did not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sent an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for girls and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007).

14.3 Education in the United States

Education in the United States is a massive social institution involving millions of people and billions of dollars. In 2018, over 76 million people, almost one-fourth of the U.S. population, attend school at all levels. This number includes over 35.6 million in grades pre-K through 8, 15.1 million in high school, and 19.9 million in college (including graduate and professional school). They attend some 133,000 elementary and secondary schools, with $654 billion worth of funding for the 2018-19 school year (National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). Education is a huge social institution.

Correlates of Educational Attainment

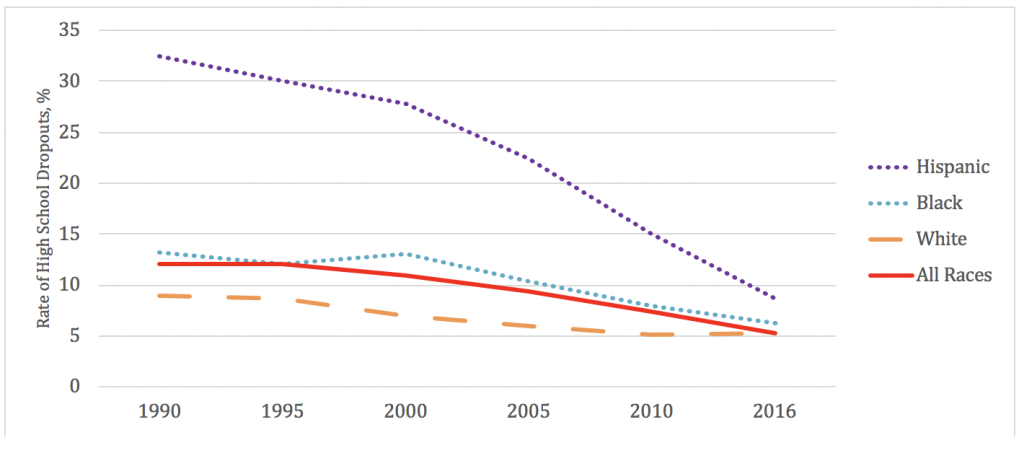

About 70% of U.S. high school graduates enroll in college the following fall. This is a very high figure by international standards, as college in many other industrial nations is reserved for the very small percentage of the population who pass rigorous entrance exams, whereas higher education in the United States is open to all who graduate high school. Even though that is true, our chances of achieving a college degree are greatly determined at birth, as social class and race/ethnicity have a significant effect on access to and completion of college. For instance, Figure 14.2 “Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 1990-2016” shows how race and ethnicity affect high school dropout rates. The dropout rate is highest for Latinos and lowest for whites. However, note the decline in dropout rates over time for all groups, especially Hispanic/Latino students, whose dropout rate in 2016 was roughly ¼ of the rate it was in 1990.

Figure 14.2 Race, Ethnicity, and High School Dropout Rate, 16–24-Year-Olds, 1990-2016

Similarly, one way of illustrating how income and race/ethnicity affect the chances of achieving a college degree is to examine the percentage of high school graduates who enroll in college following graduation and who ultimately complete a college degree.

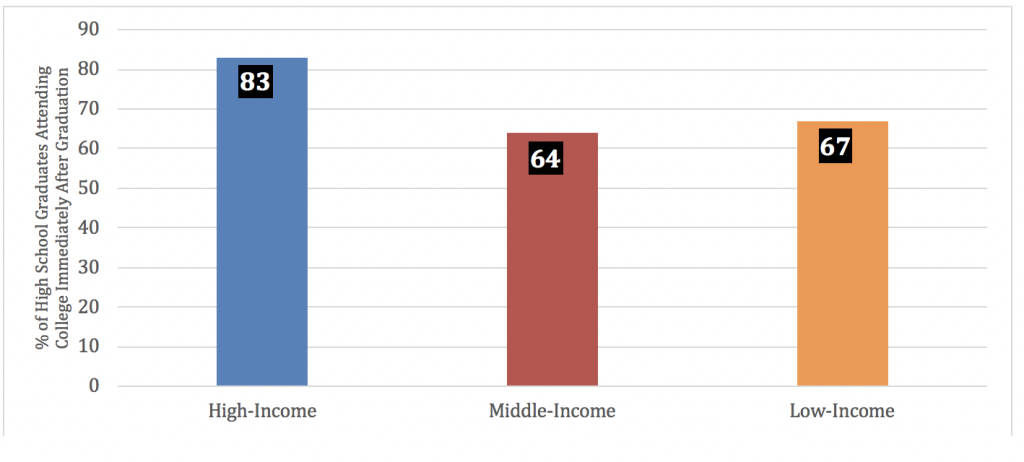

As Figure 14.3 “Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2016” shows, students from families in the highest income bracket are more likely than those in the lower brackets to attend college. It’s important to note, however, that the gap in college enrollment rates between high- and low-income students has narrowed in recent decades, from a gap of 30 percentage points in 2000 to only 16 percentage points in 2016 (The Condition of Education, 2018).

Figure 14.3 Family Income and Percentage of High School Graduates Who Attend College Immediately After Graduation, 2016

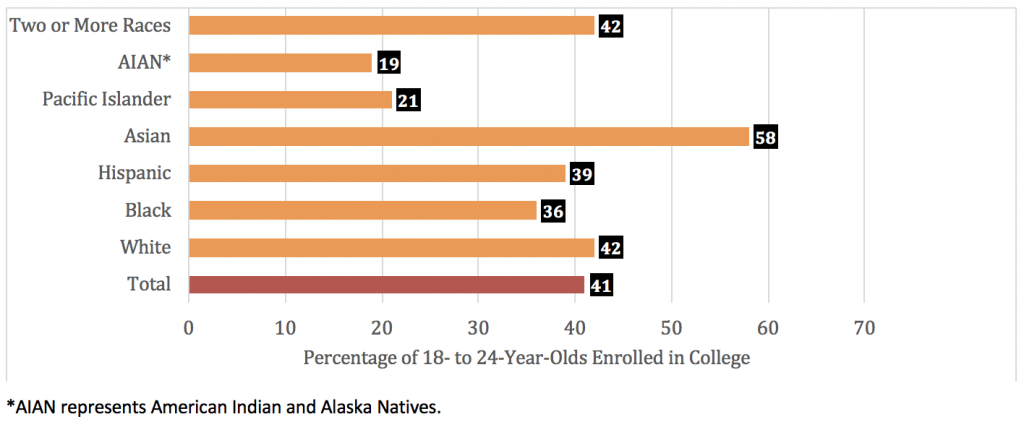

For race-ethnicity, it is useful to examine the percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in college in order to compare across groups. As shown below, there is variation in college attendance within the traditionally-aged college population by race-ethnicity. With fifty-eight percent of 18- to 24-year-old enrolled in college, Asian Americans by far have the highest rate of college attendance. In comparison, American Indians/Alaskan Natives and Pacific Islanders have the lowest rates of college enrollment, at 19 and 21%, respectively. Each racial-ethnic group experiences fluctuation in college enrollment over time, however, one group that has shown consistent increases in enrollment rates from 2000 to 2016 are Hispanic Americans, who have increased enrollment from 22% to 39% (The Condition of Education, 2018).

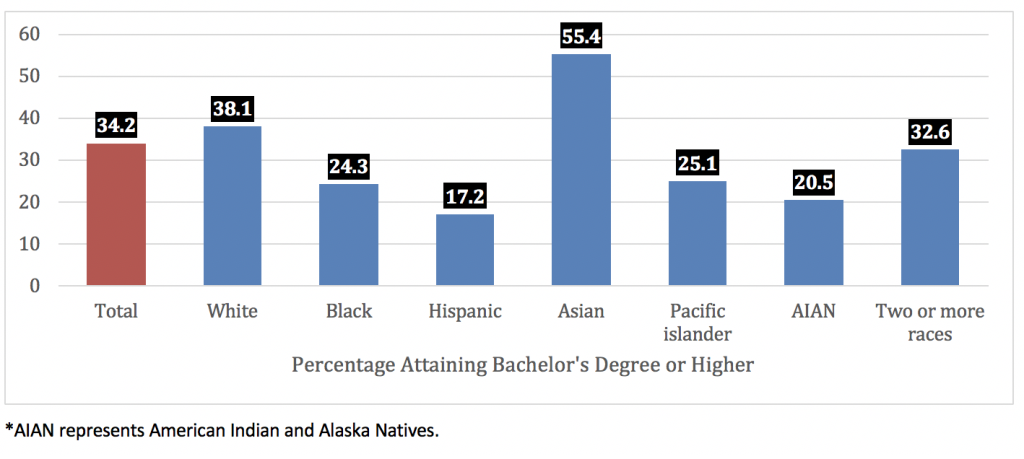

Figure 14.4 Enrollment Rates of 18- to 24-year-olds in college, by race-ethnicity, 2016

Data on retention of students once enrolled in college show that currently about 60% of students who begin seeking a bachelor’s degree complete that degree within 6 years (The Condition of Education, 2018). Additionally, rates of degree attainment varies by race-ethnicity, as shown below in Figure 14.5 ”Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older With a Bachelor’s or Higher Degree, 2017.” As demonstrated, Asian Americans have the highest rate of degree attainment, while Latinos, Native American/Alaska Natives and Black Americans are least likely to have a degree.

Figure 14.5 Race, Ethnicity, and Percentage of Persons 25 or Older with a Bachelor’s or Higher Degree, 2017

Why do Black, Latino and Native American/Alaska Natives have lower educational attainment? Two factors are commonly cited: (a) the underfunded and otherwise inadequate schools that children in these groups often attend and (b) the higher poverty of their families and lower education of their parents that often leave them ill-prepared for school even before they enter kindergarten (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009; Yeung & Pfeiffer, 2009).

Does gender affect educational attainment? The answer is yes, but perhaps not in the way you expect. In 2017, slightly more women than men hold a bachelor’s degree or higher: 34.6% of women and 33.7% of men. While women were less likely than men in earlier generations to go to college, the reverse is now true. Today, 56% of undergraduates are female.

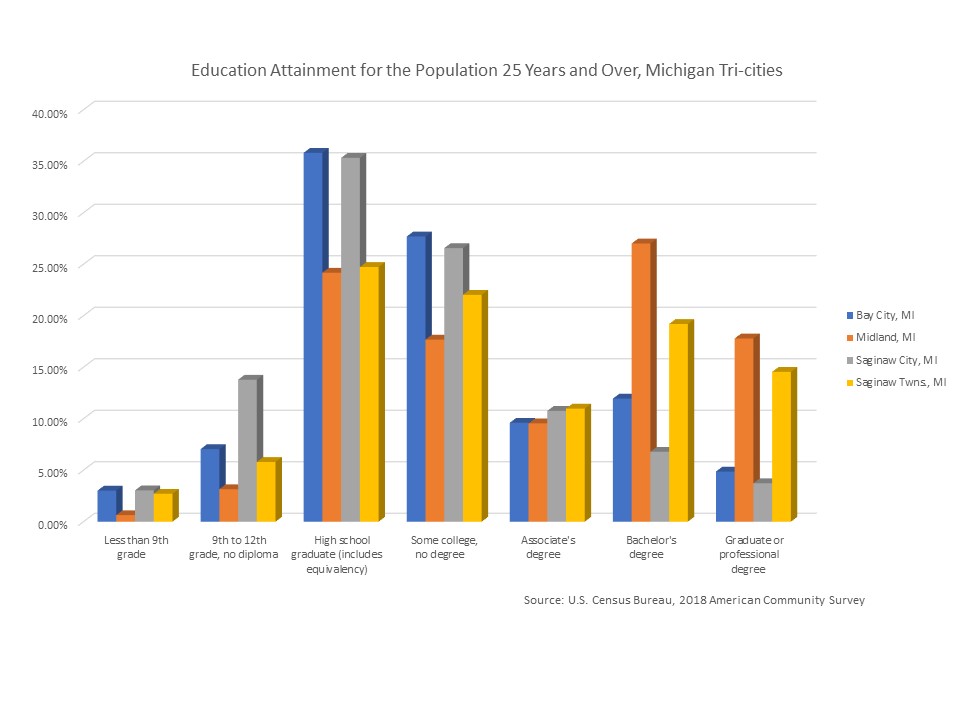

Figure 14.6 Education Attainment for the Populations 25 Years and Older, Michigan Tri-cities

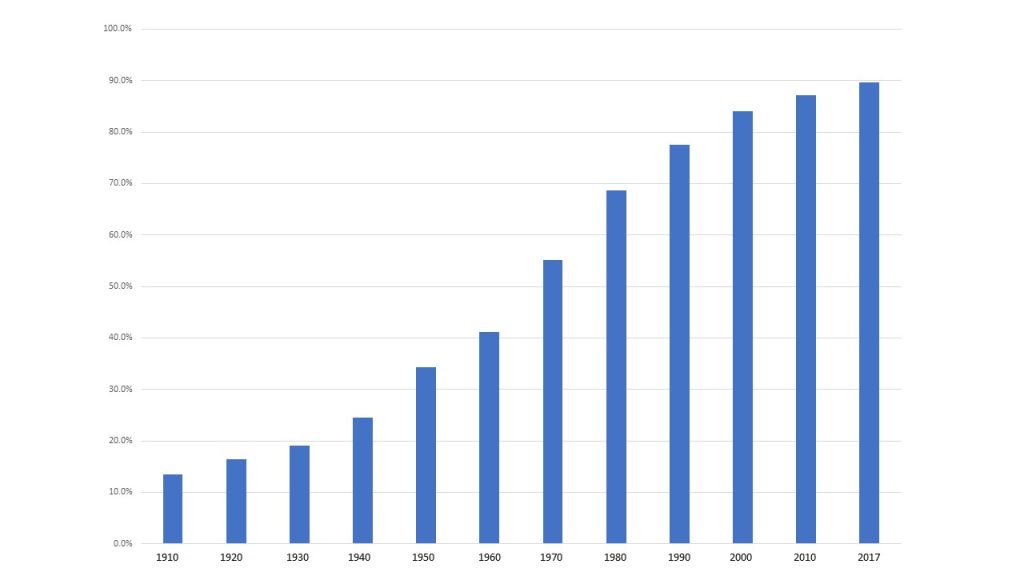

The Difference Education Makes: Income

Have you ever applied for a job that required a high school degree? Are you going to college in part because you realize you will need a college degree for a higher-paying job? As these questions imply, the United States is a credential society (Collins, 1979). This means at least two things. First, a high school or college degree (or beyond) indicates that a person has acquired the needed knowledge and skills for various jobs. Second, a degree at some level is a requirement for most jobs. As you know full well, a college degree today is a virtual requirement for a decent-paying job. Over the years the ante has been upped considerably, as in earlier generations a high school degree, if even that, was all that was needed, if only because so few people graduated from high school to begin with (see Figure 14.7 “Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2017”). With so many people graduating from high school today, a high school degree is not worth as much. Then, too, today’s technological and knowledge-based postindustrial society increasingly requires skills and knowledge that only a college education brings.

Figure 14.7 Percentage of Population 25 or Older With at Least a High School Degree, 1910–2017

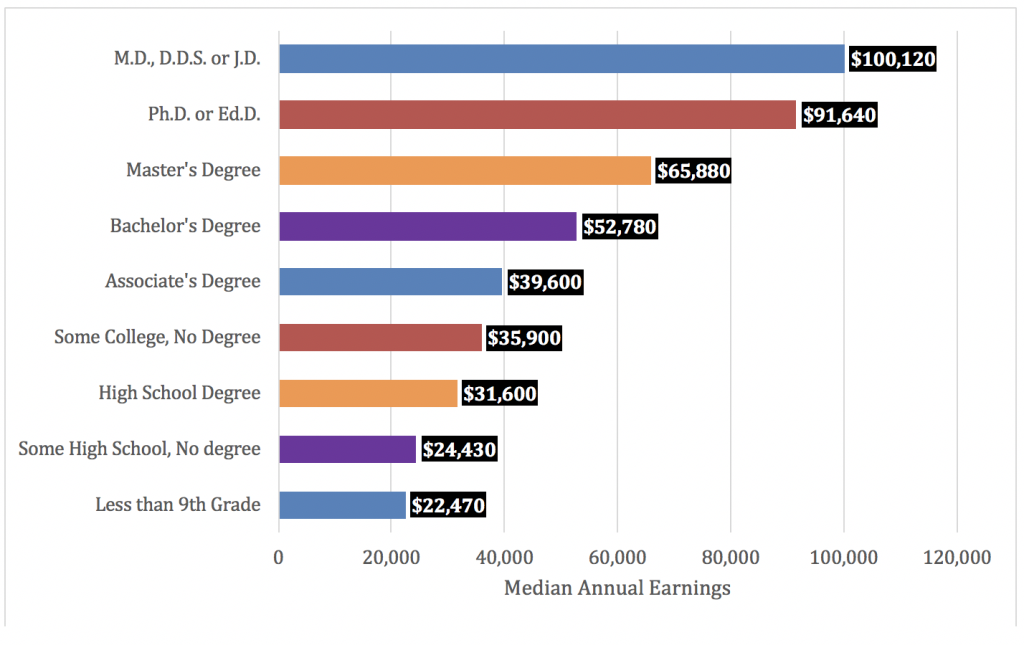

A credential society also means that people with more educational attainment have higher rates of employment and achieve higher incomes. For instance, in 2017, for people aged 25 – 64 years old, only 55.6% of those with less than a high school degree were employed, while those with a high school diploma had an employment rate of 68.4%. Comparing this data to those who had some college but did not attain a bachelor’s degree and those with a bachelor’s degree or higher, whose rates of employment were 75.3% and while 83.5%, it is clear that educational attainment plays a crucial role in job opportunity (Digest of Education Statistics, 2017).

Similarly, annual earnings are indeed much higher for people with more education (see Figure 14.8 “Median Annual Earnings of Persons 25-Years Old and Over by Level of Educational Attainment, 2016”). As earlier chapters indicated, gender and race/ethnicity affect the payoff we get from our education, but education itself still makes a huge difference for our incomes.

Figure 14.8 Median Annual Earnings of Persons 25-years Old and Over by Level of Educational Attainment, 2016

The Difference Education Makes: Attitudes

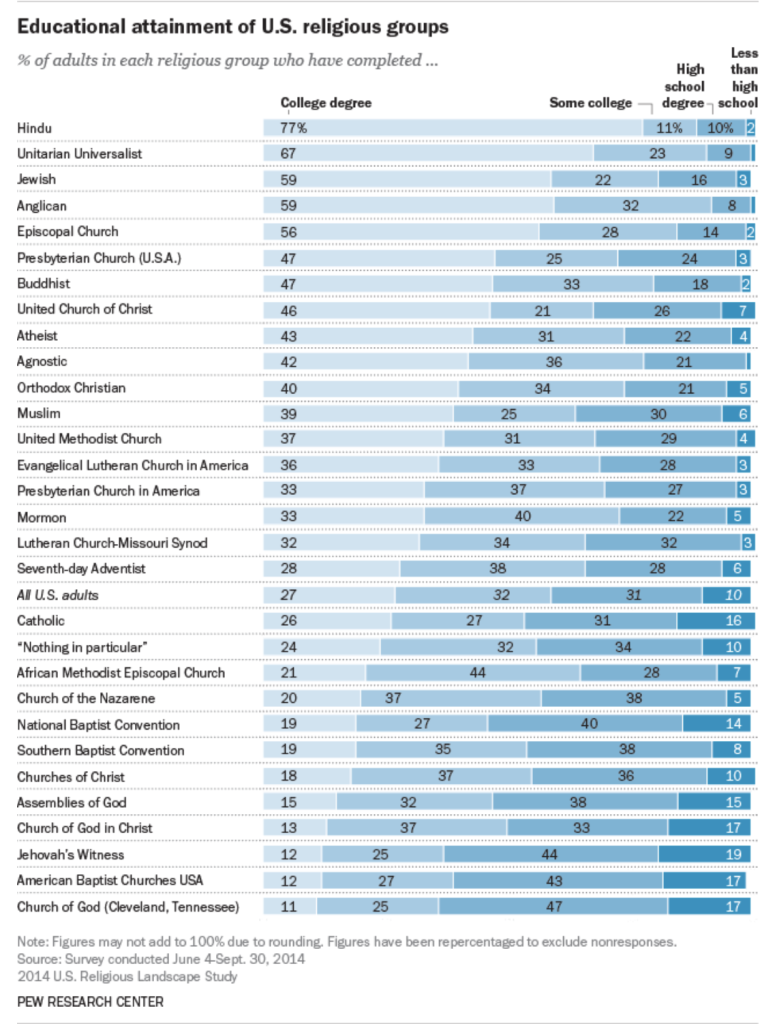

Education also makes a difference for our attitudes as indicated in Figure 14.9 “Education and Religion in the U.S.”. Researchers use different strategies to determine this effect. They compare adults with different levels of education; they compare college seniors with first-year college students; and sometimes they even study a group of students when they begin college and again when they are about to graduate. However they do so, they typically find that education leads us to be more tolerant and even approving of nontraditional beliefs and behaviors and less likely to hold various kinds of prejudices (McClelland & Linnander, 2006; Moore & Ovadia, 2006). Racial prejudice and sexism, two types of belief explored in previous chapters, all reduce with education. Education has these effects because the material we learn in classes and the experiences we undergo with greater schooling all teach us new things and challenge traditional ways of thinking and acting.

Figure 14.9 Education and Religion in the U.S.

14.4 Issues and Problems in Education

The education system today faces many issues and problems of interest not just to educators and families but also to sociologists and other social scientists. We cannot discuss all of these issues here, but we will highlight some of the most interesting and important.

Schools and Inequality

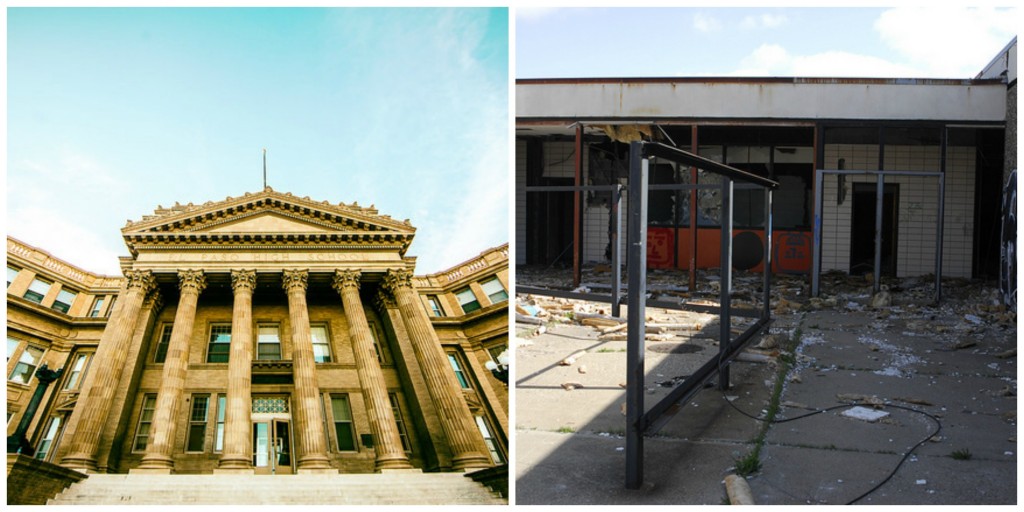

Earlier we mentioned that schools differ greatly in their funding, their conditions, and other aspects. Noted author and education critic Jonathan Kozol refers to these differences as “savage inequalities,” to quote the title of one of his books (Kozol, 1991). Kozol’s concern over inequality in the schools stemmed from his experience as a young teacher in a public elementary school in a Boston inner-city neighborhood in the 1960s. Kozol was shocked to see that his school was literally falling apart. The physical plant was decrepit, with plaster falling off the walls and bathrooms and other facilities substandard. Classes were large, and the school was so overcrowded that Kozol’s fourth-grade class had to meet in an auditorium, which it shared with another class and the school choir.

During the late 1980s, Kozol (1991) traveled around the country and systematically compared public schools in several cities’ inner-city neighborhoods to those in the cities’ suburbs. Everywhere he went, he found great discrepancies in school spending and in the quality of instruction. In schools in Camden, New Jersey, for example, spending per pupil was less than half the amount spent in the nearby, much wealthier town of Princeton. Chicago and New York City schools spent only about half the amount that some of the schools in nearby suburbs spent.

These numbers were reflected in other differences Kozol found when he visited city and suburban schools. In East St. Louis, Illinois, where most of the residents are poor and almost all are Black, schools had to shut down once because of sewage backups. The high school’s science labs were 30 to 50 years out of date when Kozol visited them; the biology lab had no dissecting kits. A history teacher had 110 students but only 26 textbooks, some of which were missing their first 100 pages. At one of the city’s junior high schools, many window frames lacked any glass, and the hallways were dark because light bulbs were missing or not working. When he visited an urban high school in New Jersey, Kozol found it had no showers for gym students, who had to wait 20 minutes to shoot one basketball because seven classes would use the school’s gym at the same time.

Contrast these schools with those Kozol visited in suburbs. A high school in a Chicago suburb had seven gyms and an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Students there could take classes in seven foreign languages. A suburban New Jersey high school offered 14 AP courses, fencing, golf, ice hockey, and lacrosse, and the school district there had 10 music teachers and an extensive music program.

From his observations, Kozol concluded that the United States is shortchanging its children in poor rural and urban areas. Poor children start out in life with many strikes against them. The schools they attend compound their problems and help ensure that the American ideal of equal opportunity for all remains just that—an ideal—rather than reality. As Kozol (1991, p. 233) observed, “All our children ought to be allowed a stake in the enormous richness of America. Whether they were born to poor white Appalachians or to wealthy Texans, to poor black people in the Bronx or to rich people in Manhasset or Winnetka, they are all quite wonderful and innocent when they are small. We soil them needlessly.”

Although the book in which Kozol reported these conditions was published almost 30 years ago, ample evidence indicates that little, if anything, has changed in the poor schools of the United States since then, with large funding differences continuing. For instance, in Connecticut, one of the wealthiest states in the country, many poor students attend schools that are among the worst in the nation (Semuels, 2016). Students who attend schools in higher income communities have far greater access to computers, updated textbooks, smaller class sizes, music and art programs, AP classes, tutoring, and the like, due to higher per pupil spending, compared to students attending schools in low income districts. For instance, in 2016, Greenwich, CT spent $6000 more per student than Bridgeport, CT, only 30 miles away, but a world of difference in terms of educational opportunity (Semuels, 2016). Even in states like Michigan, which overhauled the way it funds education in 1993, relying heavily on state sales tax rather than local property taxes, inequality still prevails due to the ability of local communities to supplement state educational funding through increases in property tax millage rates. According to researchers at the Economic Policy Institute, “…children’s social class is one of the most significant predictors—if not the single most significant predictor—of their educational success [and] …it is increasingly apparent that performance gaps by social class take root in the earliest years of children’s lives and fail to narrow in the years that follow” (Garcia and Weiss, 2017).

School Segregation

A related issue to inequality in the schools is school segregation. Before 1954, schools in the South were segregated by law (de jure segregation). Communities and states had laws that dictated which schools’ white children attended and which schools’ Black children attended. Schools were either all white or all Black, and, inevitably, white schools were much better funded than Black schools. Then in 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court outlawed de jure school segregation in its famous Brown v. Board of Education decision. In this decision the Court explicitly overturned its earlier, 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, which said that schools could be racially separate but equal. Brown rejected this conclusion as contrary to American egalitarian ideals and as also not supported by empirical evidence, which finds that segregated schools are indeed unequal. Southern school districts fought calls for school desegregation, and de jure school segregation did not really end in the South until the civil rights movement won its major victories a decade later.

Meanwhile, northern schools were also segregated and, in the years since the Brown decision, have become even more segregated. School segregation in the North stemmed, both then and now, not from the law but from neighborhood residential patterns. Because children usually go to schools near their homes, if neighborhoods are racially segregated, then the schools in these neighborhoods will also be segregated. This type of segregation is called de facto segregation.

During the 1960s and 1970s, states, municipalities, and federal courts tried to reduce de facto segregation by busing urban Black children to suburban white schools and, less often, by busing white suburban children to Black urban schools. Busing inflamed passions as perhaps few other issues during those decades (Lukas, 1985). White parents opposed it because they did not want their children bused to urban schools, where, they feared, the children would receive an inferior education and face risks to their safety. The racial prejudice that many white parents shared heightened their concerns over these issues. Black parents were more likely to see the need for busing, but they, too, wondered about its merits, especially because it was their children who were bused most often and faced racial hostility when they entered formerly all-white schools.

Today many children continue to go to schools that are segregated because of neighborhood residential patterns, a situation that Kozol (2005) calls “apartheid schooling.” In fact, 1988 was the year in which Black students experienced the highest level of school integration. Due to the termination of desegregation plans resulting from a more conservative Supreme Court in the 1990’s, the percentage of intensely segregated non-white schools (in which less than 10% of students are white) has more than tripled (Orfield, et. al., 2016). The states where Black and Latino students are most segregated, according to the Civil Rights Project, are New York, Illinois, Maryland, California, Michigan and New Jersey (Orfield, et. al., 2016). Table 14.1 “Percentage of Black Students in 90-100% Non-White Schools,” shows the degree of intensely segregated schools in these states.

Table 14.1 Percentage of Black Students in 90-100% Non-White Schools

|

State |

Percentage of Black Students in Intensely Segregated Non-White Schools |

|

New York |

65.8% |

|

Illinois |

59.6% |

|

Maryland |

53.7% |

|

New Jersey |

49.2% |

|

Michigan |

48.7% |

|

California |

47.9% |

Source: Data from Orfield, Gary, et al. Brown at 62: School Segregation by Race, Poverty and State. Civil Rights Project, 16 May 2016, www.civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-62-school-segregation-by-race-poverty-and-state/Brown-at-62-final-corrected-2.pdf.

Similarly, Latino student face high degrees of segregation in California, Texas and New York, with over half of Latino students enrolled in intensely segregated non-white schools (Orfield, et. al., 2016). In addition to racial-ethnic segregation, social class segregation also prevails, resulting in the phenomenon of “double segregation.” From 1993 – 2013, the proportion of poor students in predominantly Black schools has increased from 36.7% to 67.9%. In this same timeframe, for Latino students, the percentage has increased from 45.6 to 67.9%. Such trends result in isolation from racial-ethnic and social class diversity, and high levels of exposure to problems that afflict poor communities (Orfield, et. al., 2016). According to researchers at UCLA’s Civil Rights Project, “intense racial separation and concentrated poverty in schools that offer inferior opportunities fundamentally undermine the American belief that all children deserve an equal educational opportunity…” and school integration is necessary to ensure that all students “…are prepared to understand and live successfully in a society that moves beyond separation toward mutual respect and integration” (Orfield, et. al., 2016).

School Vouchers and School Choice

Another issue involving schools today is school choice. In a school choice program, the government gives parents certificates, or vouchers, that they can use as tuition at private or parochial (religious) schools. In addition, charter schools and magnet schools offer alternative educational settings within the public-school framework. Currently, 86.2% of students in grades 1 – 12 attend traditional public schools, while 4.5% attend public charter schools, 9.5% attend private schools and 3.3% (aged 5 – 17) are homeschooled (Digest of Education Statistics, 2017).

Advocates of school choice programs say they give poor parents an option for high-quality education they otherwise would not be able to afford. These programs, the advocates add, also help improve the public schools by forcing them to compete for students with their private and parochial counterparts. In order to keep a large number of parents from moving their children to charter schools or using vouchers to send their children to the private schools, public schools have to upgrade their facilities, improve their instruction, and undertake other steps to make their brand of education an attractive alternative. In this way, school choice advocates argue, choice has “competitive impact” that forces public schools to make themselves more attractive to prospective students (Walberg, 2007).

Critics of school choice programs say they hurt the public schools by decreasing their enrollments and therefore their funding. Public schools do not have the money now to compete with private and parochial ones, and neither will they have the money to compete with them if school choice becomes more widespread. Critics also worry that school choice will lead to a “brain drain” of the most academically motivated children and families from low-income schools (Caldas & Bankston, 2005).

Because school choice programs and school voucher systems are still relatively new, scholars have not yet had time to assess whether they improve or worsen the academic achievement of the students who attend them. Some studies do find small improvements, while others find no significant difference in academic outcome. One study of school choice on student outcomes in Chicago found no positive impact on academic outcomes, however, school choice students did have lower incidents of disciplinary actions, fewer arrests and lower rates of juvenile incarceration (Cullen, Jacob and Levitt, 2006). Although there is similarly little research on the impact of school choice programs on funding and other aspects of public-school systems, some evidence does indicate a negative impact. In Milwaukee, for example, enrollment decline from the use of vouchers cost the school system $26 million in state aid during the 1990s, forcing a rise in property taxes to replace the lost funds. Because the students who left the Milwaukee school system came from most of its 157 public schools, only a few left any one school, diluting the voucher system’s competitive impact. Another city, Cleveland, also lost state aid in the late 1990s because of the use of vouchers, and there, too, the competitive impact was small. Thus, although school choice programs may give some families alternatives to public schools, they might not have the competitive impact on public schools that their advocates claim, and they may cost public school systems state aid (Cooper, 1999; Lewin, 1999).

School Violence

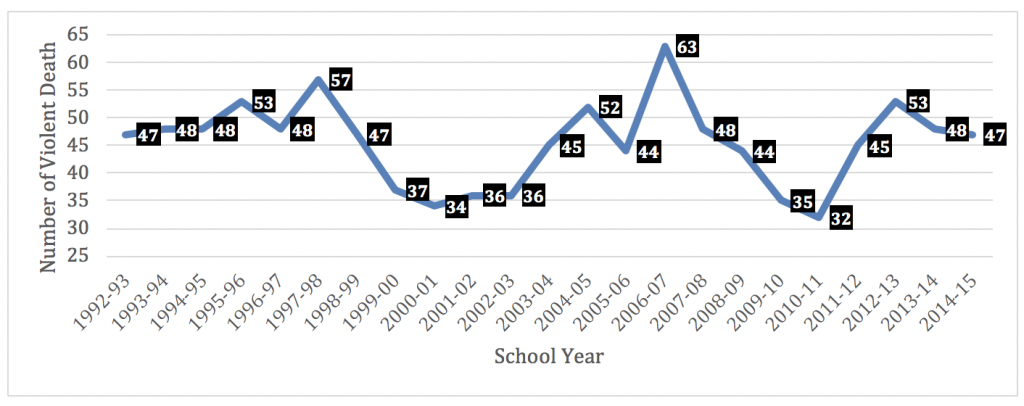

The issue of school violence won major headlines during the 1990s, when numerous children, teachers, and other individuals died from violent acts (including suicide) in the nation’s schools. From 1992 – 1999, this included 248 deaths on school property, during travel to and from school, or at a school-related event, for an average of about 35 violent deaths per year (Zuckoff, 1999). Against this backdrop, the infamous April 1999 school shootings at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where two students murdered 12 other students and one teacher before killing themselves, led to national soul-searching over the causes of teen and school violence and on possible ways to reduce it. Since the Columbine murders, it is reported that 220,000 students have experienced gun violence while at school (as victims and/or witnesses), with 143 deaths and 289 injuries of children, educators and other individuals (Cox, et. al, 2018). With the exception of large-scale shootings, such as those at Sandy Hook Elementary School and Marjorie Stoneman Douglas High School, most of these incidents get little news coverage.

Fortunately, violent deaths in schools remain rare events. Below, Figure 14.10 “Number of students (aged 5 – 18), staff, and other nonstudent school-associated violent deaths (including homicides, suicides and legal intervention deaths involving law enforcement), School Years 1992–93 to 2014–15” demonstrates both the rarity and consistency in this number. As this trend indicates, the risk of school violence should not be exaggerated: statistically speaking, schools are very safe. Less than 1% of homicides involving school-aged children take place in or near school. Roughly 56 million students attend elementary and secondary schools, with 27 student homicides a year on average, so the chances are about one in 2.1 million that a student will be killed at school. Bullying is a more common problem, with about one-third of students reporting being bullied annually (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2010).

Figure 14.10 Number of students (aged 5 – 18), staff, and other nonstudent school-associated violent deaths (including homicides, suicides and legal intervention deaths involving law enforcement), School Years 1992–93 to 2014–15

To reduce school violence, many school districts have zero-tolerance policies involving weapons. These policies call for automatic suspension or expulsion of a student who has anything resembling a weapon for any reason. For better or worse, however, there have been many instances in which these policies have been applied too rigidly. In one example, a 6-year-old boy in Delaware excitedly took his new camping utensil—a combination of knife, fork, and spoon—from Cub Scouts to school to use at lunch. He was suspended for having a knife and ordered to spend 45 days in reform school. His mother said her son certainly posed no threat to anyone at school, but school officials replied that their policy had to be strictly enforced because it is difficult to determine who actually poses a threat from who does not (Urbina, 2009).

Ironically, one reason many school districts have very strict policies is to avoid the racial discrimination that was seen to occur in districts whose officials had more discretion in deciding which students needed to be suspended or expelled. In these districts, Black students with weapons or “near-weapons” were more likely than white students with the same objects to be punished in this manner. Regardless of the degree of discretion afforded officials in zero-tolerance policies, these policies have not been shown to be effective in reducing school violence and may actually raise rates of violence by the students who are suspended or expelled under these policies (Skiba & Rausch, 2006).

Focus on Higher Education

The issues and problems discussed so far in this chapter primarily concern the nation’s elementary and secondary schools in view of their critical importance for tens of millions of children and for the nation’s social and economic wellbeing. However, issues also affect higher education, and we examine a few of them here.

Cost

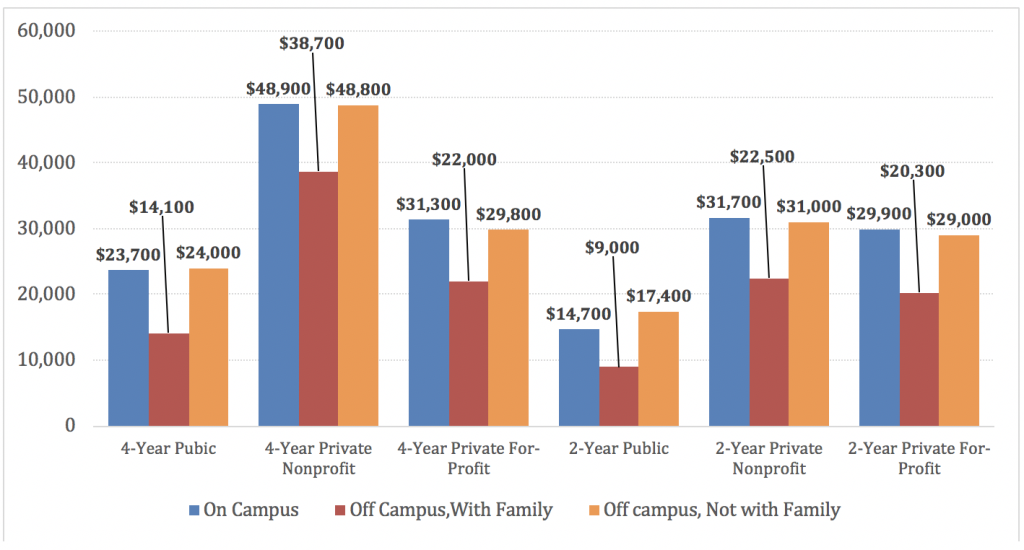

Perhaps the most important issue is that higher education, at least at 4-year institutions, is quite expensive and can cost tens of thousands of dollars per year. The average cost in 2016-17 for students at all institutions, including tuition, fees, room and board was $23,091 (Digest of Education Statistics, 2017). Of course, this figure varies by the type of college or university a student attends.

In 2016, 64% of college students attended a 4-year institution, with the other 36% attending a 2-year institution, including public, private nonprofit and private for-profit institutions. Figure 14.11 “Cost of Attending College for First-Time Full-Time Undergraduate by Institution Type and Living Arrangement, 2016-17” demonstrates both the high cost of attending college, as well as the variation in cost found in the United States.

Figure 14.11 “Annual Cost of Attending College for First-Time Full-Time Undergraduate by Institution Type and Living Arrangement, 2016-17”

As is obvious from the chart above, there is a wide range of costs associated with attending college. The cost for tuition and fees alone ranges from $9000 at 2-year public schools to $38,7000 at 4-Year Private nonprofit schools. Adding roughly $10,000 in living expenses means these costs can soar to up to nearly $50,000 per year. Books and supplies can average an additional $1,000 per year for students.

Scholarships and other financial aid reduce these costs for many students. Private institutions actually collect only about 67% of their published tuition and fees because of the aid they provide, and public institutions collect only about 82% (Stripling, 2010). However, students who receive aid may still have high bills and graduate with huge loans to repay. In 2017, Americans owed over $1.3 trillion for student loans (Cilluffo, 2017). For all student loan borrowers, the median debt is $17,000, causing many new graduates to work two jobs in order to service their debt (Cilluffo, 2017).

Social Class and Race in Admissions

We saw earlier in this chapter that Black, Latino, and low-income students are less likely to attend college. This fact raises important questions about the lack of diversity in college admissions and campus life. Chapter 9 “Race and Ethnicity” discussed the debate over racially based affirmative action in higher education. Partly because affirmative action is so controversial, attention has begun to focus on the low numbers of low-income students at many colleges and universities, especially the more selective institutions that rank highly in ratings issued by U.S. News & World Report and other sources. Many education scholars and policymakers feel that increasing the number of low-income students would not only help these students but also increase campus diversity along the lines of socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity (since BIPOC students are more likely to be from low-income backgrounds). Efforts to increase the number of low-income students, these experts add, would avoid the controversy that has surrounded affirmative action.

In response to this new attention to social class, colleges and universities have begun to increase their efforts to attract and retain low-income students. The dean of admissions and financial aid at Harvard University summarized these efforts as follows: “I honestly cannot think of any admissions person I know who is not looking—as sort of a major criteria of how well their year went—at how well they did in attracting people of different economic backgrounds” (Schmidt, 2010).

As part of their strategy to attract and retain low-income students, Harvard and other selective institutions are now providing financial aid to cover all or most of the students’ expenses. Despite these efforts, however, the U.S. higher education system has become more stratified by social class in recent decades: the richest students now occupy a greater percentage of the enrollment at the most selective institutions than in the past, while the poorest students occupy a greater percentage of the enrollment at less selective 4-year institutions and at community colleges (Schmidt, 2010).

Graduation Rates

For the sakes of students and their colleges and universities, it is important that as many students as possible go on to earn their diplomas. However, only 60% of students at 4-year institutions graduate within 6 years. This figure varies by type of institution. At 4-year public institutions, 59% of first-time, full-time students graduate within 6 years, while at private nonprofit institutions the rate is 66%, compared to the 26% who graduate from private for-profit institutions within the same timeframe (Digest of Education Statistics, 2017).

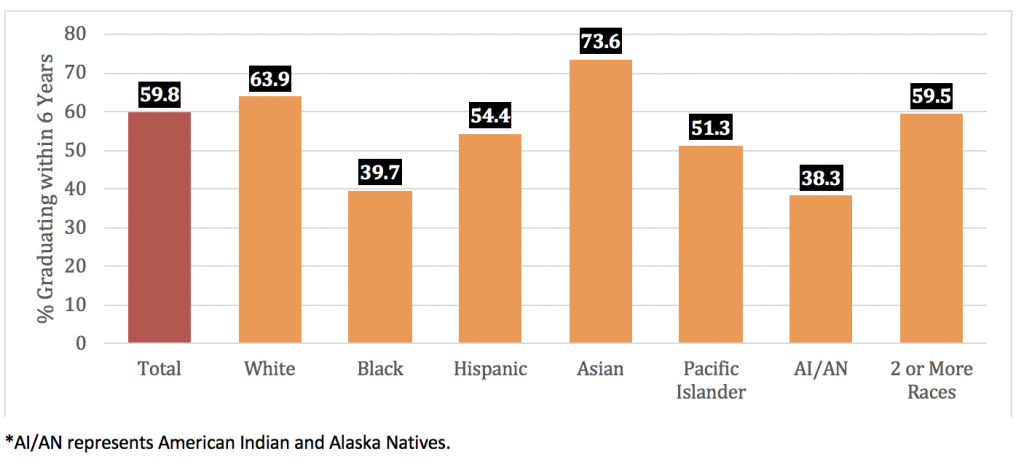

The 60% overall rate masks a racial/ethnic difference in graduation rates. As shown below in Figure 14.12 “Graduation Rate for First-Time, Full-Time Students Enrolled at 4-Year Colleges and Universities within 6-years (2010 Starting Cohort), by Race and Ethnicity,” the rate of graduation varies significantly, with the lowest rates for Native American /Alaska Native and Black students, and the highest for Asian American students.

Figure 14.12 Graduation Rate for First-Time, Full-Time Students Enrolled at 4-Year Colleges and Universities within 6-years (2010 Starting Cohort), by Race and Ethnicity

At some institutions, the graduation rates of Latino and Black students match those of whites, thanks in large part to efforts by these institutions to provide resources to students of color. As one expert on this issue explains, “What colleges do for students of color powerfully impacts the futures of these young people and that of our nation” (Gonzalez, 2010). Another expert placed this issue into a larger context: “For both moral and economic reasons, colleges need to ensure that their institutions work better for all the students they serve” (Stephens, 2010).

In this regard, it is important to note that the graduation rate of low-income students from 4-year institutions is much lower than the graduation rate of wealthier students. Low-income students drop out at higher rates because of academic and financial difficulties and family problems (Berg, 2010). Their academic and financial difficulties are intertwined. Low-income students often have to work many hours per week during the academic year to be able to pay their bills. Because their work schedules reduce the time they have for studying, their grades may suffer. This general problem has been made worse by cutbacks in federal grants to low-income students that began during the 1980s. These cutbacks forced low-income students to rely increasingly on loans, which have to be repaid. This fact leads some to work more hours during the academic year to limit the loans they must take out, and their increased work schedule again may affect their success.

Low-income students face additional difficulties beyond the financial (Berg, 2010). Their writing and comprehension skills upon entering college are often weaker than those of wealthier students. If they are first-generation college students (meaning that neither parent went to college), they often have problems adjusting to campus life and living amid students from much more advantaged backgrounds.

14.5 Religion

Social Issues in the News

“America’s First Muslim College to Open This Fall,” the headline said. The United States has hundreds of colleges and universities run by or affiliated with the Catholic Church and several Protestant and Jewish denominations, and now it was about to have its first Muslim college. Zaytuna College in Berkeley, California, had just sent out acceptance letters to students who would make up its inaugural class in the fall of 2010. The school’s founder said it would be a Muslim liberal arts college whose first degrees would be in Islamic law and theology and in the Arabic language. The chair of the college’s academic affairs committee explained, “We are trying to graduate well-rounded students who will be skilled in a liberal arts education with the ability to engage in a wider framework of society and the variety of issues that confront them.…We are thinking of how to set up students for success. We don’t see any contradiction between religious and secular subjects.” The college planned to rent a building in Berkeley during its first several years and was doing fund-raising to pay for the eventual construction or purchase of its own campus. It hoped to obtain academic accreditation within a decade. Because the United States has approximately 6 million Muslims whose numbers have tripled since the 1970s, college officials were optimistic that their new institution would succeed. An official with the Islamic Society of North America, which aids Muslim communities and organizations and provides chaplains for the U.S. military, applauded the new college. “It tells me that Muslims are coming of age,” he said. “This is one more thing that makes Muslims part of the mainstream of America. It is an important part of the development of our community.” (Oguntoyinbo, 2010)

The opening of any college is normally cause for celebration, but the news about this particular college aroused a mixed reaction. Some people wrote positive comments on the Web page on which this news article appeared, but two anonymous writers left very negative comments. One asked, “What if they teach radical Islam?” while the second commented, “Dose [sic] anyone know how Rome fell all those years ago? We are heading down the same road.”

As the reaction to this news story reminds us, religion and especially Islam have certainly been hot topics since 9/11. Many political and religious leaders urge Americans to practice religious tolerance, and advocacy groups have established programs and secondary school curricula to educate the public and students, respectively. Colleges and universities have responded with courses and workshops on Islamic culture, literature, and language. The controversy over Islam is just one example of the strong passions that religion and religious differences often arouse.

This remainder of this chapter presents a sociological understanding of religion by examining religion as a social institution and by sketching its history and practice throughout the world today. We then turn to the several types of religious organizations before concluding with a discussion of various aspects of religion in the United States.

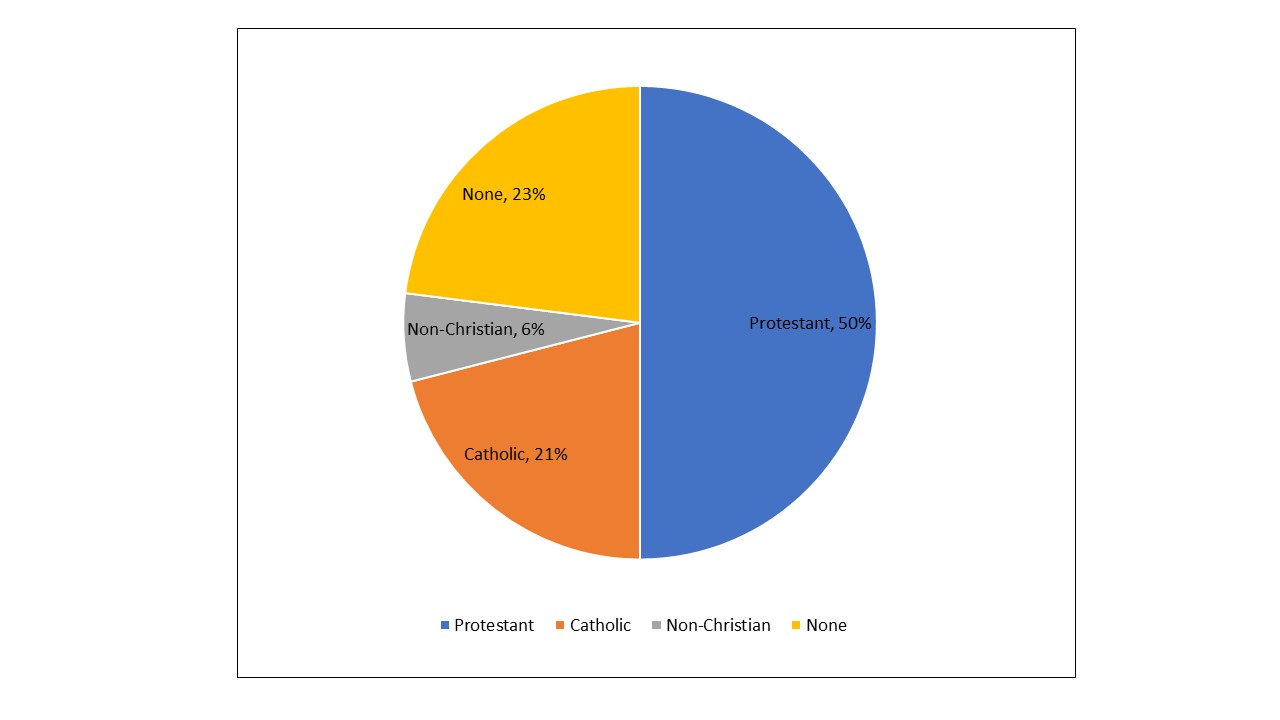

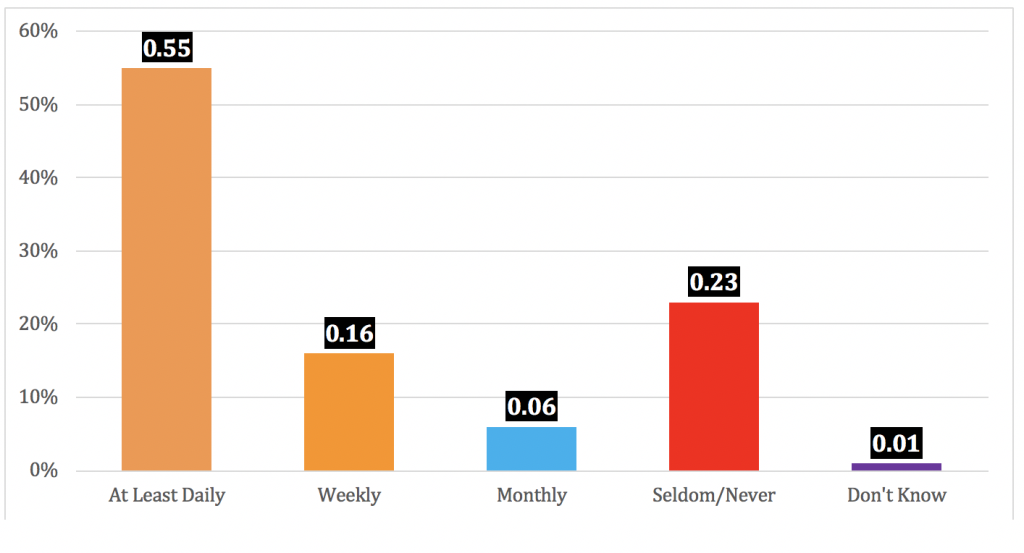

14.6 Religion as a Social Institution

Religion clearly plays an important role in American life. Most Americans believe in a deity, over half pray daily, and more than 1/3 attend religious services weekly. We tend to think of religion in individual terms because religious beliefs and values are highly personal for many people. However, religion is also a social institution, as it involves patterns of beliefs and behavior that help a society meet its basic needs. More specifically, religion is the set of beliefs and practices regarding sacred things that help a society understand the meaning and purpose of life.

Because it is such an important social institution, religion has long been a key sociological topic. Émile Durkheim (1915/1947) observed long ago that every society has beliefs about things that are supernatural and awe-inspiring and beliefs about things that are more practical and down-to-earth. He called the former beliefs sacred beliefs and the latter beliefs profane beliefs. Religious beliefs and practices involve the sacred: they involve things our senses cannot readily observe, and they involve things that inspire in us awe, reverence, and even fear.

Durkheim did not try to prove or disprove religious beliefs. Religion, he acknowledged, is a matter of faith, and faith is not provable or disprovable through scientific inquiry. Rather, Durkheim tried to understand the role played by religion in social life and the impact on religion of social structure and social change. In short, he treated religion as a social institution.

Sociologists since his time have treated religion in the same way. Anthropologists, historians, and other scholars have also studied religion. Historical work on religion reminds us of the importance of religion since the earliest societies, while comparative work on contemporary religion reminds us of its importance throughout the world today.

14.7 Religion in Historical and Cross-Cultural Perspective

Every known society has practiced religion, although the nature of religious belief and practice has differed from one society to the next. Prehistoric people turned to religion to help them understand birth, death, and natural events such as hurricanes. They also relied on religion for help in dealing with their daily needs for existence: good weather, a good crop, an abundance of animals to hunt (Noss & Grangaard, 2008).

Although the world’s most popular religions today are monotheistic (believing in one god), many societies in ancient times, most notably Egypt, Greece, and Rome, were polytheistic (believing in more than one god). You have been familiar with their names since childhood: Aphrodite, Apollo, Athena, Mars, Zeus, and many others. Each god “specialized” in one area; Aphrodite, for example, was the Greek goddess of love, while Mars was the Roman god of war (Noss & Grangaard, 2008).

During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church dominated European life. The Church’s control began to weaken with the Protestant Reformation, which began in 1517 when Martin Luther, a German monk, spoke out against Church practices. By the end of the century, Protestantism had taken hold in much of Europe. Another founder of sociology, Max Weber, argued a century ago that the rise of Protestantism in turn led to the rise of capitalism. In his great book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Weber wrote that Protestant belief in the need for hard work and economic success as a sign of eternal salvation helped lead to the rise of capitalism and the Industrial Revolution (Weber, 1904/1958). Although some scholars challenge Weber’s views for several reasons, including the fact that capitalism also developed among non-Protestants, his analysis remains a compelling treatment of the relationship between religion and society.

Moving from Europe to the United States, historians have documented the importance of religion since the colonial period. Many colonists came to the new land to escape religious persecution in their home countries. The colonists were generally very religious, and their beliefs guided their daily lives and, in many cases, the operation of their governments and other institutions. In essence, government and religion were virtually the same entity in many locations, and church and state were not separate. Church officials performed many of the duties that the government performs today, and the church was not only a place of worship but also a community center in most of the colonies (Gaustad & Schmidt, 2004). The Puritans of what came to be Massachusetts refused to accept religious beliefs and practices different from their own and persecuted people with different religious views. They expelled Anne Hutchinson in 1637 for disagreeing with the beliefs of the Puritans’ Congregational Church and hanged Mary Dyer in 1660 for practicing her Quaker faith.

Key World Religions Today

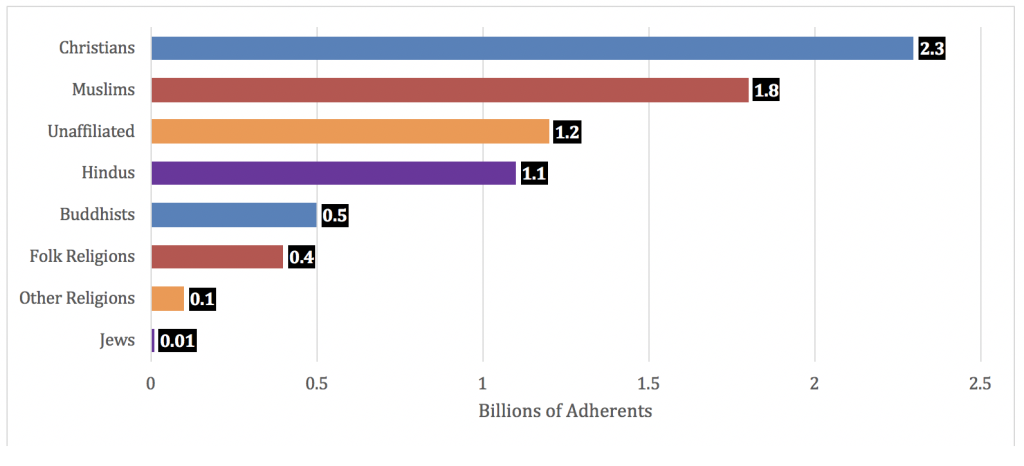

Today the world’s largest religion is Christianity, to which more than 2 billion people, or about one-third the world’s population, subscribe (see Figure 14.13 “Number of Adherent, by Religious Affiliation, 2015”). Christianity began 2,000 years ago in Palestine under the charismatic influence of Jesus of Nazareth and today is a Western religion, as most Christians live in the Americas and in Europe. Beginning as a cult, Christianity spread through the Mediterranean and later through Europe before becoming the official religion of the Roman Empire. Today, dozens of Christian denominations exist in the United States and other nations. Their views differ in many respects, but generally they all regard Jesus as the son of God, and many believe that salvation awaits them if they follow his example (Young, 2010).

Figure 14.13 Number of Adherent, by Religious Affiliation, 2015

The second largest religion is Islam, which includes about 1.8 billion Muslims, most of them in the Middle East, northern Africa, and parts of Asia. Muhammad founded Islam in the 600s A.D. and is regarded today as a prophet who was a descendant of Abraham. Whereas the sacred book of Christianity and Judaism is the Bible, the sacred book of Islam is the Koran. The Five Pillars of Islam guide Muslim life: (a) the acceptance of Allah as God and Muhammad as his messenger; (b) ritual worship, including daily prayers facing Mecca, the birthplace of Muhammad; (c) observing Ramadan, a month of prayer and fasting; (d) giving alms to the poor; and (e) making a holy pilgrimage to Mecca at least once before one dies.

The third largest religion is Hinduism, which includes more than 800 million people, most of whom live in India and Pakistan. Hinduism began about 2000 B.C. and, unlike Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, has no historic linkage to any one person and no real belief in one omnipotent deity. Hindus live instead according to a set of religious precepts called dharma. For these reasons Hinduism is often called an ethical religion. Hindus believe in reincarnation, and their religious belief in general is closely related to India’s caste system, as an important aspect of Hindu belief is that one should live according to the rules of one’s caste.

Buddhism is another key religion and claims almost 400 million followers, most of whom live in Asia. Buddhism developed out of Hinduism and was founded by Siddhartha Gautama more than 500 years before the birth of Jesus. Siddhartha is said to have given up a comfortable upper-caste Hindu existence for one of wandering and poverty. He eventually achieved enlightenment and acquired the name of Buddha, or “enlightened one.” His teachings are now called the dhamma, and over the centuries they have influenced Buddhists to lead a moral life. Like Hindus, Buddhists generally believe in reincarnation, and they also believe that people experience suffering unless they give up material concerns and follow other Buddhist principles.

Another key religion is Judaism, which claims more than 13 million adherents throughout the world, most of them in Israel and the United States. Judaism began about 4,000 years ago when, according to tradition, Abraham was chosen by God to become the progenitor of his “chosen people,” first called Hebrews or Israelites and now called Jews. The Jewish people have been persecuted throughout their history, with anti-Semitism having its ugliest manifestation during the Holocaust of the 1940s, when 6 million Jews died at the hands of the Nazis. One of the first monotheistic religions, Judaism relies heavily on the Torah, which is the first five books of the Bible, and the Talmud and the Mishnah, both collections of religious laws and ancient rabbinical interpretations of these laws. The three main Jewish dominations are the Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform branches, listed in order from the most traditional to the least traditional. Orthodox Jews take the Bible very literally and closely follow the teachings and rules of the Torah, Talmud, and Mishnah, while Reform Jews think the Bible is mainly a historical document and do not follow many traditional Jewish practices. Conservative Jews fall in between these two branches.

A final key religion in the world today is Confucianism, which reigned in China for centuries but was officially abolished in 1949 after the Chinese Revolution ended in Communist control. People who practice Confucianism in China today do so secretly, and its number of adherents is estimated at some 5 or 6 million. Confucianism was founded by K’ung Fu-tzu, from whom it gets its name, about 500 years before the birth of Jesus. His teachings, which were compiled in a book called the Analects, were essentially a code of moral conduct involving self-discipline, respect for authority and tradition, and the kind treatment of everyone. Despite the official abolition of Confucianism, its principles continue to be important for Chinese family and cultural life.

As this overview indicates, religion takes many forms in different societies. No matter what shape it takes, however, religion has important consequences. These consequences can be both good and bad for the society and the individuals in it. Sociological perspectives expand on these consequences, and we now turn to them.

14.8 Sociological Perspectives on Religion

Sociological perspectives on religion aim to understand the functions religion serves, the inequality and other problems it can reinforce and perpetuate, and the role it plays in our daily lives (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011). The following “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what these perspectives say.

Theory Snapshot

|

Theory |

Major Assumption |

|

Functionalism |

Religion serves several functions for society. These include (a) giving meaning and purpose to life, (b) reinforcing social unity and stability, (c) serving as an agent of social control of behavior, (d) promoting physical and psychological well-being, and (e) motivating people to work for positive social change. |

|

Conflict Perspective |

Religion reinforces and promotes social inequality and social conflict. It helps convince the poor to accept their lot in life, and it leads to hostility and violence motivated by religious differences. |

|

Interactionism |

This perspective focuses on the ways in which individuals interpret their religious experiences. It emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once they are regarded as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to people’s lives. |

The Functions of Religion

Much of the work of Émile Durkheim stressed the functions that religion serves for society regardless of how it is practiced or of what specific religious beliefs a society favors. Durkheim’s insights continue to influence sociological thinking today on the functions of religion.

First, religion gives meaning and purpose to life. Many things in life are difficult to understand. That was certainly true, as we have seen, in prehistoric times, but even in today’s highly scientific age, much of life and death remains a mystery, and religious faith and belief help many people make sense of the things science cannot tell us.

Second, religion reinforces social unity and stability. This was one of Durkheim’s most important insights. Religion strengthens social stability in at least two ways. First, it gives people a common set of beliefs and thus is an important agent of socialization. Second, the communal practice of religion, as in houses of worship, brings people together physically, facilitates their communication and other social interaction, and thus strengthens their social bonds.

A third function of religion is related to the one just discussed. Religion is an agent of social control and thus strengthens social order. Religion teaches people moral behavior and thus helps them learn how to be good members of society. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, the Ten Commandments are perhaps the most famous set of rules for moral behavior.

A fourth function of religion is greater psychological and physical well-being. Religious faith and practice can enhance psychological well-being by being a source of comfort to people in times of distress and by enhancing their social interaction with others in places of worship. Many studies find that people of all ages, not just the elderly, are happier and more satisfied with their lives if they are religious. Religiosity also apparently promotes better physical health, and some studies even find that religious people tend to live longer than those who are not religious (Moberg, 2008). We return to this function later.

A final function of religion is that it may motivate people to work for positive social change. Religion played a central role in the development of the Southern civil rights movement a few decades ago. Religious beliefs motivated Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists to risk their lives to desegregate the South. Black churches in the South also served as settings in which the civil rights movement held meetings, recruited new members, and raised money (Morris, 1984).

Religion, Inequality, and Conflict

Religion has all of these benefits, but, according to conflict theory, it can also reinforce and promote social inequality and social conflict. This view is partly inspired by the work of Karl Marx, who said that religion was the “opiate of the masses” (Marx, 1964). By this he meant that religion, like a drug, makes people happy with their existing conditions. Marx repeatedly stressed that workers needed to rise up and overthrow the bourgeoisie. To do so, he said, they needed first to recognize that their poverty stemmed from their oppression by the bourgeoisie. But people who are religious, he said, tend to view their poverty in religious terms. They think it is God’s will that they are poor, either because he is testing their faith in him or because they have violated his rules. Many people believe that if they endure their suffering, they will be rewarded in the afterlife. Their religious views lead them not to blame the capitalist class for their poverty and thus not to revolt. For these reasons, said Marx, religion leads the poor to accept their fate and helps maintain the existing system of social inequality.

Religion also promotes gender inequality by presenting negative stereotypes about women and by reinforcing traditional views about their subordination to men (Klassen, 2009). A declaration a decade ago by the Southern Baptist Convention that a wife should “submit herself graciously” to her husband’s leadership reflected traditional religious belief (Gundy-Volf, 1998).

As the Puritans’ persecution of non-Puritans illustrates, religion can also promote social conflict, and the history of the world shows that individual people and whole communities and nations are quite ready to persecute, kill, and go to war over religious differences. We see this today and in the recent past in central Europe, the Middle East, and Northern Ireland. Jews and other religious groups have been persecuted and killed since ancient times. Religion can be the source of social unity and cohesion, but over the centuries it also has led to persecution, torture, and wanton bloodshed.

News reports going back since the 1990s indicate a final problem that religion can cause, and that is sexual abuse, at least in the Catholic Church. As you undoubtedly have heard, an unknown number of children were sexually abused by Catholic priests and deacons in the United States, Canada, and many other nations going back at least to the 1960s. There is much evidence that the Church hierarchy did little or nothing to stop the abuse or to sanction the offenders who were committing it, and that they did not report it to law enforcement agencies. Various divisions of the Church have paid tens of millions of dollars to settle lawsuits. The numbers of priests, deacons, and children involved will almost certainly never be known, but it is estimated that at least 4,400 priests and deacons in the United States, or about 4% of all such officials, have been accused of sexual abuse, although fewer than 2,000 had the allegations against them proven (Terry & Smith, 2006). Given these estimates, the number of children who were abused probably runs into the thousands.

Symbolic Interactionism and Religion

While functional and conflict theories look at the macro aspects of religion and society, symbolic interactionism looks at the micro aspects. It examines the role that religion plays in our daily lives and the ways in which we interpret religious experiences. For example, it emphasizes that beliefs and practices are not sacred unless people regard them as such. Once we regard them as sacred, they take on special significance and give meaning to our lives. Symbolic interactionists study the ways in which people practice their faith and interact in houses of worship and other religious settings, and they study how and why religious faith and practice have positive consequences for individual psychological and physical well-being.

Religious symbols indicate the value of the symbolic interactionist approach. A crescent moon and a star are just two shapes in the sky, but together they constitute the international symbol of Islam. A cross is merely two lines or bars in the shape of a “t,” but to tens of millions of Christians it is a symbol with deeply religious significance. A Star of David consists of two superimposed triangles in the shape of a six-pointed star, but to Jews around the world it is a sign of their religious faith and a reminder of their history of persecution.

Religious rituals and ceremonies also illustrate the symbolic interactionist approach. They can be deeply intense and can involve crying, laughing, screaming, trancelike conditions, a feeling of oneness with those around you, and other emotional and psychological states. For many people they can be transformative experiences, while for others they are not transformative but are deeply moving nonetheless.

14.9 Types of Religious Organizations

Many types of religious organizations exist in modern societies. Sociologists usually group them according to their size and influence. Categorized this way, three types of religious organizations exist: church, sect, and cult (Emerson, Monahan, & Mirola, 2011). A church further has two subtypes: the ecclesia and denomination. We first discuss the largest and most influential of the types of religious organization, the ecclesia, and work our way down to the smallest and least influential, the cult.

Church: The Ecclesia and Denomination

A church is a large, bureaucratically organized religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society. Two types of church organizations exist. The first is the ecclesia, a large, bureaucratic religious organization that is a formal part of the state and has most or all of a state’s citizens as its members. As such, the ecclesia is the national or state religion. People ordinarily do not join an ecclesia; instead they automatically become members when they are born. A few ecclesiae exist in the world today, including Islam in Saudi Arabia and some other Middle Eastern nations, the Catholic Church in Spain, the Lutheran Church in Sweden, and the Anglican Church in England.

As should be clear, in an ecclesiastic society there may be little separation of church and state, because the ecclesia and the state are so intertwined. In some ecclesiastic societies, such as those in the Middle East, religious leaders rule the state or have much influence over it, while in others, such as Sweden and England, they have little or no influence. In general the close ties that ecclesiae have to the state help ensure they will support state policies and practices. For this reason, ecclesiae often help the state solidify its control over the populace.

The second type of church organization is the denomination, a large, bureaucratic religious organization that is closely integrated into the larger society but is not a formal part of the state. In modern pluralistic nations, several denominations coexist. Most people are members of a specific denomination because their parents were members. They are born into a denomination and generally consider themselves members of it the rest of their lives, whether or not they actively practice their faith, unless they convert to another denomination or abandon religion altogether.

The Megachurch

A relatively recent development in religious organizations is the rise of the so-called megachurch, a church at which more than 2,000 people worship every weekend on the average. Several dozen have at least 10,000 worshippers (Priest, Wilson, & Johnson, 2010; Warf & Winsberg, 2010); the largest U.S. megachurch, Lakewood Church in Houston, has more than 40,000 worshippers and is nicknamed a “gigachurch.” There are more than 1,300 megachurches in the United States, a steep increase from the 50 that existed in 1970, and their total membership exceeds 4 million. About half of today’s megachurches are in the South, and only 5% are in the Northeast. About one-third are nondenominational, and one-fifth are Southern Baptist, with the remainder primarily of other Protestant denominations. A third spend more than 10% of their budget on ministry in other nations. Some have a strong television presence, with Americans in the local area or sometimes around the country watching services and/ or preaching by televangelists and providing financial contributions in response to information presented on the television screen.

Compared to traditional, smaller churches, megachurches are more concerned with meeting their members’ practical needs in addition to helping them achieve religious fulfillment. Some even conduct market surveys to determine these needs and how best to address them. As might be expected, their buildings are huge by any standard, and they often feature bookstores, food courts, and sports and recreation facilities. They also provide day care, psychological counseling, and youth outreach programs. Their services often feature electronic music and light shows.

Although megachurches are popular, they have been criticized for being so big that members are unable to develop the close bonds with each other and with members of the clergy characteristic of smaller houses of worship. Their supporters say that megachurches involve many people in religion who would otherwise not be involved.

Sect

A sect is a relatively small religious organization that is not closely integrated into the larger society and that often conflicts with at least some of its norms and values. Typically a sect has broken away from a larger denomination in an effort to restore what members of the sect regard as the original views of the denomination. Because sects are relatively small, they usually lack the bureaucracy of denominations and ecclesiae and often also lack clergy who have received official training. Their worship services can be intensely emotional experiences, often more so than those typical of many denominations, where worship tends to be more formal and restrained. Members of many sects typically proselytize and try to recruit new members into the sect. If a sect succeeds in attracting many new members, it gradually grows, becomes more bureaucratic, and, ironically, eventually evolves into a denomination. Many of today’s Protestant denominations began as sects, as did the Mennonites, Quakers, and other groups. The Amish in the United States are perhaps the most well-known example of a current sect.

Cult

A cult is a small religious organization that is at great odds with the norms and values of the larger society. Cults are similar to sects but differ in at least three respects. First, they generally have not broken away from a larger denomination and instead originate outside the mainstream religious tradition. Second, they are often secretive and do not proselytize as much. Third, they are at least somewhat more likely than sects to rely on charismatic leadership based on the extraordinary personal qualities of the cult’s leader.

Although the term cult today raises negative images of crazy, violent, small groups of people, it is important to keep in mind that major world religions, including Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, and denominations such as the Mormons all began as cults. Research challenges several popular beliefs about cults, including the ideas that they brainwash people into joining them and that their members are mentally ill. In a study of the Unification Church (Moonies), Eileen Barker (1984) found no more signs of mental illness or brainwashing among people who joined the Moonies than in those who did not.