6

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Identify differences between aggregates, categories and groups, including primary, secondary and reference groups.

- Understand in-groups and out-groups and their relationship.

- Recall and explain the results of Asch and Milgram experiments.

- Recognize group behaviors such as the diffusion of responsibility, groupthink, and the iron law of oligarchy.

- Describe the three types of formal organizations.

- Define the characteristics of bureaucracies and discuss advantages and disadvantages.

6.1 Social Groups

A social group consists of two or more people who regularly interact on the basis of mutual expectations and who share a common identity. It is easy to see from this definition that we all belong to many types of social groups: our families, our different friendship groups, the sociology class and other courses we attend, our workplaces, the clubs and organizations to which we belong, and so forth. Except in rare cases, it is difficult to imagine any of us living totally alone. Even people who live by themselves still interact with family members, coworkers, and friends and to this extent still have several group memberships.

It is important here to distinguish social groups from two related concepts: social categories and social aggregates. A social category is a collection of individuals who have at least one attribute in common but otherwise do not necessarily interact. Women is an example of a social category. All women have at least one thing in common, their biological sex, even though they do not interact. Asian Americans is another example of a social category, as all Asian Americans have two things in common, their ethnic background and their residence in the United States, even if they do not interact or share any other similarities. As these examples suggest, gender, race, and ethnicity are the basis for several social categories. Other common social categories are based on our religious preference, geographical residence, and social class.

Falling between a social category and a social group is the social aggregate, which is a collection of people who are in the same place at the same time but who otherwise do not necessarily interact, except in the most superficial of ways, or have a common identity. The crowd at a sporting event and the audience at a movie or play are common examples of social aggregates. These collections of people are not a social category, because the people are together physically, and they are also not a group, because they do not really interact and do not have a common identity unrelated to being in the crowd or audience at that moment. That said, a sociologist could find patterns of categorical relations between members of a seemingly unrelated population. For instance, compare the aggregate at a Whole Foods store to the aggregate at a Walmart store and you will see find similar categories. With these distinctions laid out, let’s return to our study of groups by looking at the different types of groups that sociologists note.

Primary and Secondary Groups

A common distinction is made between primary groups and secondary groups. A primary group is usually small, is characterized by extensive interaction and strong emotional ties, and endures over time. Members of such groups care a lot about each other and identify strongly with the group. Indeed, their membership in a primary group gives them much of their social identity. Charles Horton Cooley, who proposed the looking-glass self concept discussed previously, called these groups primary, because they are the first groups we belong to and because they are so important for social life. The family is the primary group that comes most readily to mind, but small peer friendship groups, whether they are your high school friends, an urban street gang, or middle-aged adults who get together regularly, are also primary groups.

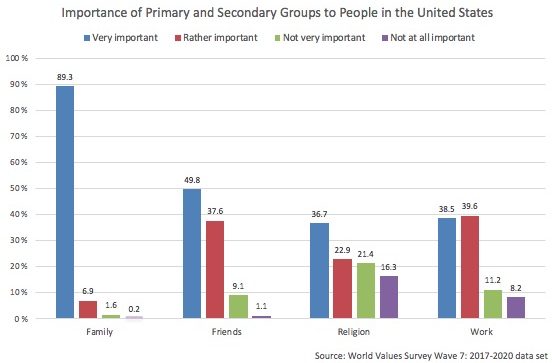

Our primary groups play significant roles in so much that we do. Survey evidence bears this out for the family. Figure 6.1 shows that an overwhelming majority of Americans say their family is “very important” in their lives. Friends also rank as important, especially when Very Important and Rather Important are combined. Would you say the same for your family and friends?

Figure 6.1 Percentage of People in the United States Who Say Their Family, Friends, Religion, and Work are Very Important, Rather Important, Not Very Important, or Not at All Important in Their Lives

Ideally, our primary groups give us emotional warmth and comfort in good times and bad and provide us an identity and a strong sense of loyalty and belonging. Our primary group memberships are thus important for such things as our happiness and mental health. Much research, for example, shows rates of suicide and emotional problems are lower among people involved with social support networks such as their families and friends than among people who are pretty much alone (Maimon & Kuhl, 2008). However, our primary group relationships may not be ideal or healthy, and they may cause us much mental and emotional distress. In this regard, the family as a primary group is the setting for much physical and sexual violence committed against women, children (Gosselin, 2010), and men, to an important but also statistically lesser extent.

Although primary groups are the most important ones in our lives, we belong to many more secondary groups, which are groups that are larger and more impersonal and exist, often for a relatively short time, to achieve a specific purpose. Secondary group members feel less emotionally attached to each other than do primary group members and do not identify as much with their group nor feel as loyal to it. This does not mean secondary groups are unimportant, as society could not exist without them, but they still do not provide the potential emotional benefits for their members that primary groups ideally do.

The sociology class for which you are reading this book is likely an example of a secondary group, as are the clubs and organizations on your campus to which you might belong. Other secondary groups include religious, business, governmental, and civic organizations. In some of these groups, members get to know each other better than in other secondary groups, but their emotional ties and intensity of interaction generally remain much weaker than in primary groups.

Within different institutions, the definitions of primary and secondary groups can flex. For example, within the institution of family, your primary group might be the people you see often, and your secondary group affiliation might be the strangers at the 10-year family reunion. Within the institution of religion, your faith or denomination might be a massive, anonymous secondary identity, but you might have a smaller study group within your congregation that has characteristics of a primary group. Within the institution of education, your college or university has the characteristics of a secondary group, but your classrooms, especially if you move forward as a student cohort, may take on some primary group characteristics. Consider that you likely experienced more primary than secondary group characteristics if you went to a small K-12 school where you were with the same group a students for more than a decade. Primary and Secondary group memberships are on a continuum from more to less emotional connection, commitment, responsibly, anonymity, and smaller to larger group size.

Reference Groups

Primary and secondary groups can act both as our reference groups or as groups that set a standard for guiding our own behavior and attitudes. The family we belong to obviously affects our actions and views, as, for example, there were probably times during your adolescence when you decided not to do certain things with your friends to avoid disappointing or upsetting your parents. On the other hand, your friends regularly acted during your adolescence as a reference group, and you probably dressed the way they did or did things with them, even against your parents’ wishes, precisely because they were your reference group. Some of our reference groups are groups to which we do not belong but to which we nonetheless want to belong. A small child, for example, may dream of becoming an astronaut and dress like one and play like one. Some high school students may not belong to the “cool” clique in school but may still dress like the members of this clique, either in hopes of being accepted as a member or simply because they admire the dress and style of its members.

Samuel Stouffer and colleagues (Stouffer, Suchman, DeVinney, Star, & Williams, 1949) demonstrated the importance of reference groups in a well-known study of American soldiers during World War II. This study sought to determine why some soldiers were more likely than others to have low morale. Surprisingly, Stouffer found that the actual, “objective” nature of their living conditions affected their morale less than whether they felt other soldiers were better or worse off than they were. Even if their own living conditions were fairly good, they were likely to have low morale if they thought other soldiers were doing better. Another factor affecting their morale was whether they thought they had a good chance of being promoted. Soldiers in units with high promotion rates were, paradoxically, more pessimistic about their own chances of promotion than soldiers in units with low promotion rates. Evidently the former soldiers were dismayed by seeing so many other men in their unit getting promoted and felt worse off as a result. In each case, Stouffer concluded, the soldiers’ views were shaped by their perceptions of what was happening in their reference group of other soldiers. They felt deprived relative to the experiences of the members of their reference group and adjusted their views accordingly. The concept of relative deprivation captures this process. Later in this chapter, relative deprivation is described as the essential first step to a social movement.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

Members of primary and some secondary groups feel loyal to those groups and take pride in belonging to them. We call such groups in-groups. Fraternities, sororities, sports teams, and juvenile gangs are examples of in-groups. Members of an in-group often end up competing with members of another group for various kinds of rewards. This other group is called an out-group. The competition between in-groups and out-groups is often friendly, as among members of intramural teams during the academic year when they vie in athletic events. Sometimes, however, in-group members look down their noses at out-group members and even act very hostilely toward them. Rival fraternity members at several campuses have been known to get into fights and trash each other’s houses. More seriously, street gangs attack each other, and hate groups such as skinheads and the Ku Klux Klan have committed violence against people of color, Jews, and other individuals they consider members of out-groups. As these examples make clear, in-group membership can promote very negative attitudes toward the out-groups with which the in-groups feel they are competing. These attitudes are especially likely to develop in times of rising unemployment and other types of economic distress, as in-group members are apt to blame out-group members for their economic problems (Olzak, 1992).

Social Networks

These days in the job world we often hear of “networking,” or taking advantage of your connections with people who have connections to other people who can help you land a job. You do not necessarily know these “other people” who ultimately can help you, but you do know the people who know them. Your ties to the other people are weak or nonexistent, but your involvement in this network may nonetheless help you find a job.

Modern life is increasingly characterized by such social networks, or the totality of relationships that link us to other people and groups and through them to still other people and groups. Some of these relationships involve strong bonds, while other relationships involve weak bonds (Granovetter, 1983). Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat and other Web sites have made possible networks of a size unimaginable just a decade ago. Social networks are important for many things, including getting advice, borrowing small amounts of money, and finding a job. When you need advice or want to borrow $5 or $10, to whom do you turn? The answer is undoubtedly certain members of your social networks—your friends, family, and so forth.

All other things being equal, if you had two people standing before you, one employed as a vice president in a large corporation and the other working part time at a fast-food restaurant, which person do you think would be more likely to know a physician or two personally? Your answer is probably the corporate vice president. The point is that factors such as our social class and occupational status, our race and ethnicity, and our gender affect how likely we are to have social networks that can help us get jobs, good medical care, and other advantages. As just one example, a study of three working-class neighborhoods in New York City—one white, one Black, and one Latino—found that white youths were more involved through their parents and peers in job-referral networks than youths in the other two neighborhoods and thus were better able to find jobs, even if they had been arrested for delinquency (Sullivan, 1989). This study suggests that even if we look at people of different races and ethnicities in roughly the same social class, whites have an advantage over people of color in the employment world.

Gender also matters in the employment world. In many businesses, there still exists an “old boys’ network,” in which male executives with job openings hear about male applicants from male colleagues and friends. Male employees already on the job tend to spend more social time with their male bosses than do their female counterparts. These related processes make it more difficult for females than for males to be hired and promoted (Barreto, Ryan, & Schmitt, 2009). To counter these effects and to help support each other, some women form networks where they meet, talk about mutual problems, and discuss ways of dealing with these problems. An example of such a network is The Links, Inc., a community service group of 12,000 professional Black women whose name underscores the importance of networking (http://www.linksinc.org/index.shtml). Its members participate in 270 chapters in 42 states; Washington, DC; and the Bahamas. Every two years, more than 2,000 Links members convene for a national assembly at which they network, discuss the problems they face as professional women of color, and consider fund-raising strategies for the causes they support.

Groups and Social Change

As we consider ways to try to improve society, or change it, the role of groups and organizations becomes very important. Social change is when norms and values of a culture and society change over time. There are, arguably, many explanations for what causes social change, as discussed earlier. This section addresses the role of the group in social change.

One individual can certainly make a difference, but it is much more common for any difference to be made by individuals acting together—that is, by a group. In this regard, it is very clear that groups of many types have been and will continue to be vehicles for social reform and social change of many kinds. Many of the rights and freedoms Americans enjoy today were the result of committed efforts by social reform groups and social movements of years past: the abolitionist movement, the women’s suffrage movement and contemporary women’s movement, the labor movement, the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, and the environmental movement, to name just a few.

These social movements are all intentional actions done collectively by a group who has organized to change something about society. Social movements do not come out of nowhere; they originate in social groups that feel entitled to something they do not have access to but should. This feeling of relative deprivation is an essential component in social change because a social movement would likely not move forward if the members of the group did not all believe that they deserved something more. Recall the discussion of societal transformation; social movements initiated by people who are feeling deprived compared to others in their society can even cause a replacement of the dominant ideology, as suggested by Marx’s theory.

Once a group recognizes its relative deprivation, coalescence of the movement takes place. People begin to plan events that will draw media attention and get the word out; this also helps the group obtain financial support. As the number of members grows, the group strengthens socially and politically. A social movement often evolves into a formally organized entity with little to no effort. As funds increase, the group is able to afford paid staff and so a hierarchy of authority develops, with leaders at the top. Buildings and other infrastructure are added to the list of costs. Once in the Institutionalization phase, a social movement works much like a business so much so that it can be hard to maintain focus on the original goals of the social movement. Social movements eventually end with accomplishing its goals, an evolution to a new goal or a failure to accomplish its goals.

In contemporary societies, there are innumerable social service and social advocacy groups that are attempting to bring about changes to benefit a particular constituency or the greater society, and you might well belong to one of these groups on your campus or in your home community. All such groups, past, present, and future, are vehicles for social reform and social change, or at least have the potential for becoming such vehicles.

6.2 Group Dynamics and Behavior

Social scientists have studied how people behave in groups and how groups affect people’s behavior, attitudes, and perceptions (Gastil, 2009). Their research underscores the importance of groups for social life, but it also points to the dangerous influence groups can sometimes have on their members.

The Importance of Group Size

The distinction made earlier between small primary groups and larger secondary groups reflects the importance of group size for the functioning of a group, the nature of its members’ attachments, and the group’s stability. If you have ever taken a very small class, say fewer than 15 students, you probably noticed that the class atmosphere differed markedly from that of a large lecture class you may have been in. In the small class, you were able to know the professor better, and the students in the room were able to know each other better. Attendance in the small class was probably more regular than in the large lecture class.

Over the years, sociologists and other scholars have studied the effects of group size on group dynamics. One of the first to do so was German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918), who discussed the effects of groups of different sizes. The smallest group, of course, is the two-person group, or dyad, such as a married couple or two people engaged to be married or at least dating steadily. In this smallest of groups, Simmel noted, relationships can be very intense emotionally (as you might know from personal experience) but also very unstable and short lived: if one person ends the relationship, the dyad ends as well.

A triad, or three-person group, involves relationships that are still fairly intense, but it is also more stable than a dyad. A major reason for this, said Simmel, is that if two people in a triad have a dispute, the third member can help them reach some compromise that will satisfy all the triad members. The downside of a triad is that two of its members may become very close and increasingly disregard the third member, reflecting the old saying that “three’s a crowd.” As one example, some overcrowded college dorms are forced to house students in triples, or three to a room. In such a situation, suppose that two of the roommates are night owls and like to stay up very late, while the third wants lights out by 11:00 p.m. If majority rules, as well it might, the third roommate will feel very dissatisfied and may decide to try to find other roommates.

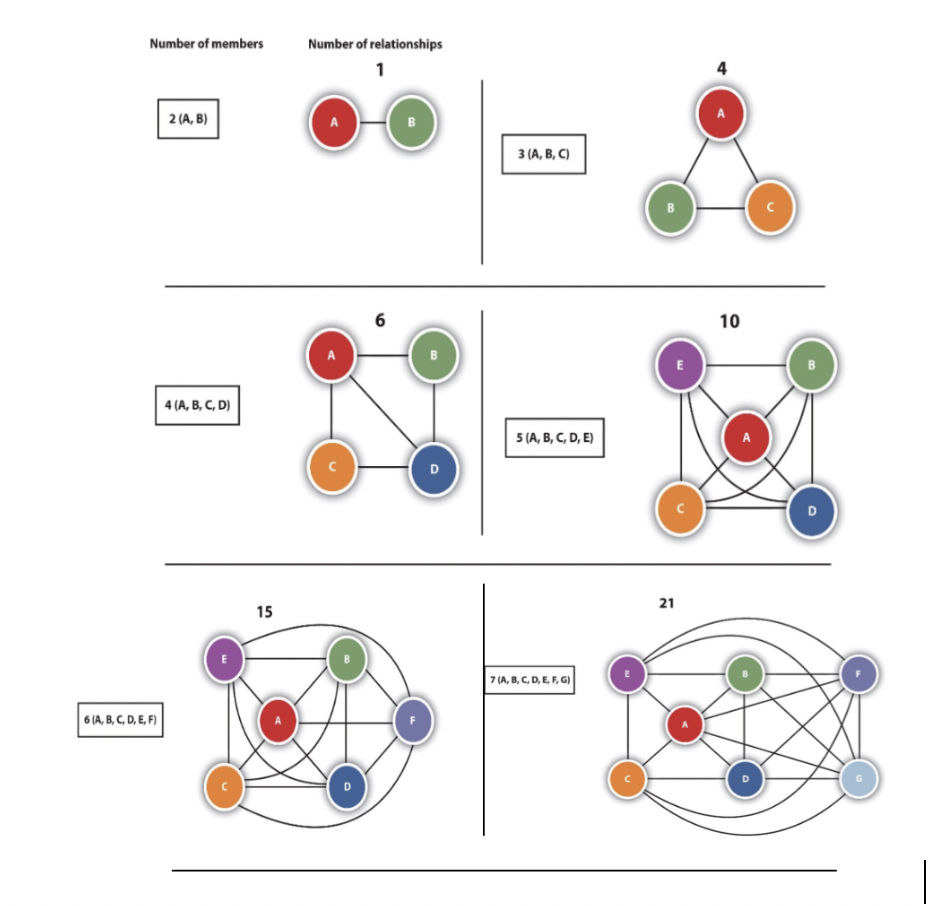

As groups become larger, the intensity of their interaction and bonding decreases, but their stability increases. The major reason for this is the sheer number of relationships that can exist in a larger group. For example, in a dyad only one relationship exists, that between the two members of the dyad. In a triad (say composed of members A, B, and C), three relationships exist: A-B, A-C, and B-C. In a four-person group, the number of relationships rises to six: A-B, A-C, A-D, B-C, B-D, and C-D. In a five-person group, 10 relationships exist, and in a seven-person group, 21 exist (see Figure 6.2 “Number of Two-Person Relationships in Groups of Different Sizes”). As the number of possible relationships rises, the amount of time a group member can spend with any other group member must decline, and with this decline comes less intense interaction and weaker emotional bonds. But as group size increases, the group also becomes more stable because it is large enough to survive any one member’s departure from the group. When you graduate from your college or university, any clubs, organizations, or sports teams to which you belong will continue despite your exit, no matter how important you were to the group, as the remaining members of the group and new recruits will carry on in your absence.

Figure 6.2 Number of Two-Person Relationships in Groups of Different Sizes

Group Leadership and Decision Making

Most groups have leaders. In the family, of course, the parents are the leaders, as much as their children sometimes might not like that. Even some close friendship groups have a leader or two who emerge over time. Virtually all secondary groups have leaders. These groups often have a charter, operations manual, or similar document that stipulates how leaders are appointed or elected and what their duties are.

Groups, Roles, and Conformity

We have seen in this and previous chapters that groups are essential for social life, in large part because they play an important part in the socialization process and provide emotional and other support for their members. As sociologists have emphasized since the origins of the discipline during the 19th century, the influence of groups on individuals is essential for social stability. This influence operates through many mechanisms, including the roles that group members are expected to play. Secondary groups such as business organizations are also fundamental to complex industrial societies such as our own.

Social stability results because groups induce their members to conform to the norms, values, and attitudes of the groups themselves and of the larger society to which they belong. As the chapter-opening news story about teenage vandalism reminds us, however, conformity to the group, or peer pressure, has a downside if it means that people might adopt group norms, attitudes, or values that are bad for some reason to hold and may even result in harm to others. Conformity is thus a double-edged sword. Unfortunately, bad conformity happens all too often, as several social-psychological experiments, to which we now turn, remind us.

Solomon Asch and Perceptions of Line Lengths

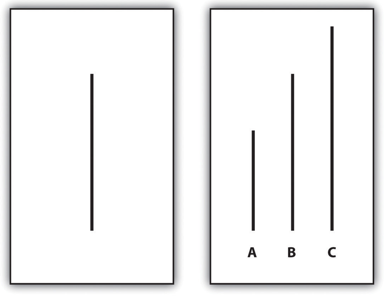

Several decades ago Solomon Asch (1958) conducted one of the first of these experiments. Consider the pair of cards in Figure 6.3 “Examples of Cards Used in Asch’s Experiment”. One of the lines (A, B, or C) on the right card is identical in length to the single line in the left card. Which is it? If your vision is up to par, you undoubtedly answered Line B. Asch showed several students pairs of cards similar to the pair in Figure 6.3 “Examples of Cards Used in Asch’s Experiment” to confirm that it was very clear which of the three lines was the same length as the single line.

Figure 6.3 Examples of Cards Used in Asch’s Experiment

Next, he had students meet in groups of at least six members and told them he was testing their visual ability. One by one he asked each member of the group to identify which of the three lines was the same length as the single line. One by one each student gave a wrong answer. Finally, the last student had to answer, and about one-third of the time the final student in each group also gave the wrong answer that everyone else was giving.

Unknown to these final students, all the other students were confederates or accomplices, to use some experimental jargon, as Asch had told them to give a wrong answer on purpose. The final student in each group was thus a naive subject, and Asch’s purpose was to see how often the naive subjects in all the groups would give the wrong answer that everyone else was giving, even though it was very clear it was a wrong answer.

After each group ended its deliberations, Asch asked the naive subjects who gave the wrong answers why they did so. Some replied that they knew the answer was wrong but they did not want to look different from the other people in the group, even though they were strangers before the experiment began. But other naive subjects said they had begun to doubt their own visual perception: they decided that if everyone else was giving a different answer, then somehow they were seeing the cards incorrectly.

Asch’s experiment indicated that groups induce conformity for at least two reasons. First, members feel pressured to conform so as not to alienate other members. Second, members may decide their own perceptions or views are wrong because they see other group members perceiving things differently and begin to doubt their own perceptive abilities. For either or both reasons, then, groups can, for better or worse, affect our judgments and our actions.

Stanley Milgram and Electric Shock

Although the type of influence Asch’s experiment involved was benign, other experiments indicate that individuals can conform in a very harmful way. One such very famous experiment was conducted by Yale University psychologist Stanley Milgram (1974), who designed it to address an important question that arose after World War II and the revelation of the murders of millions of people during the Nazi Holocaust. This question was, “How was the Holocaust possible?” Many people blamed the authoritarian nature of German culture and the so-called authoritarian personality that it inspired among German residents, who, it was thought, would be quite ready to obey rules and demands from authority figures.

Milgram wanted to see whether Germans would indeed be more likely than Americans to obey unjust authority. He devised a series of experiments and found that his American subjects were quite likely to give potentially lethal electric shocks to other people. During the experiment, a subject, or “teacher,” would come into a laboratory and be told by a man wearing a white lab coat to sit down at a table housing a machine that sent electric shocks to a “learner.” Depending on the type of experiment, this was either a person whom the teacher never saw and heard only over a loudspeaker, a person sitting in an adjoining room whom the teacher could see through a window and hear over the loudspeaker, or a person sitting right next to the teacher.

The teacher was then told to read the learner a list of word pairs, such as mother-father, cat-dog, and sun-moon. At the end of the list, the teacher was then asked to read the first word of the first word pair—for example, “mother” in our list—and to read several possible matches. If the learner got the right answer (“father”), the teacher would move on to the next word pair, but if the learner gave the wrong answer, the teacher was to administer an electric shock to the learner. The initial shock was 15 volts (V), and each time a wrong answer was given, the shock would be increased, finally going up to 450 V, which was marked on the machine as “Danger: Severe Shock.” The learners often gave wrong answers and would cry out in pain as the voltage increased. In the 200-V range, they would scream, and in the 400-V range, they would say nothing at all. As far as the teachers knew, the learners had lapsed into unconsciousness from the electric shocks and even died. In reality, the learners were not actually being shocked. Instead, the voice and screams heard through the loudspeaker were from a tape recorder, and the learners that some teachers saw were only pretending to be in agony.

Before his study began, Milgram consulted several psychologists, who assured him that no sane person would be willing to administer lethal shock in his experiments. He thus was shocked (pun intended) to find that more than half the teachers went all the way to 450 V in the experiments, where they could only hear the learner over a loudspeaker and not see him. Even in the experiments where the learner was sitting next to the teacher, some teachers still went to 450 V by forcing a hand of the screaming, resisting, but tied-down learner onto a metal plate that completed the electric circuit.

Milgram concluded that people are quite willing, however reluctantly, to obey authority even if it means inflicting great harm on others. If that could happen in his artificial experiment situation, he thought, then perhaps the Holocaust was not so incomprehensible after all, and it would be too simplistic to blame the Holocaust just on the authoritarianism of German culture. Instead, perhaps its roots lay in the very conformity to roles and group norms that makes society possible in the first place. The same processes that make society possible may also make tragedies like the Holocaust possible.

Groupthink

As these examples suggest, sometimes people go along with the desires and views f a group against their better judgments, either because they do not want to appear different or because they have come to believe that the group’s course of action may be the best one after all. Psychologist Irving Janis (1972) called this process groupthink and noted it has often affected national and foreign policy decisions in the United States and elsewhere. Group members often quickly agree on some course of action without thinking completely of alternatives. A well-known example here was the decision by President John F. Kennedy and his advisers in 1961 to aid the invasion of the Bay of Pigs in Cuba by Cuban exiles who hoped to overthrow the government of Fidel Castro. Although several advisers thought the plan ill advised, they kept quiet, and the invasion was an embarrassing failure (Hart, Stern, & Sundelius, 1997).

Groupthink is also seen in jury decision-making. Because of the pressures to reach a verdict quickly, some jurors may go along with a verdict even if they believe otherwise. In juries and other small groups, groupthink is less likely to occur if at least one person expresses a dissenting view. Once that happens, other dissenters feel more comfortable voicing their own objections (Gastil, 2009).

Diffusion of Responsibility

Similar to groupthink, the diffusion of responsibility, also known as the bystander effect, is an observable social pattern where people are less likely to act if they think others will. This pattern of behavior reflects the trend of conforming to the group. Imagine someone in the middle of busy sidewalk in New York City, crying loudly. How many people do you think would stop to ask if this person was okay? Now imagine the same individual, crying on the sidewalk of a smaller community. Would people be more likely to offer help? Psychologists have found that people are less likely to act especially in larger groups (Latané and Darley, 1968). It is believed that people do not believe that the responsibility to act rests on them if there are others who can act.

6.3 Formal Organizations

Modern societies are filled with formal organizations, or large secondary groups that follow explicit rules and procedures to achieve specific goals and tasks. Max Weber (1864–1920), one of the founders of sociology, recognized long ago that as societies become more complex, their procedures for accomplishing tasks rely less on traditional customs and beliefs and more on rational (which is to say rule-guided and impersonal) methods of decision making. The development of formal organizations, he emphasized, allowed complex societies to accomplish their tasks in the most efficient way possible (Weber, 1921/1978). Today we cannot imagine how any modern, complex society could run without formal organizations such as businesses and health-care institutions.

Types of Formal Organizations

Sociologist Amitai Etzioni (1975) developed a popular typology of organizations based on how they induce people to join them and keep them as members once they do join. His three types are utilitarian, normative, and coercive organizations.

Utilitarian organizations, (also called remunerative organizations) provide an income or some other personal benefit. Business organizations, ranging from large corporations to small Mom-and-Pop grocery stores, are familiar examples of utilitarian organizations. Colleges and universities are utilitarian organizations not only for the people who work at them but also for their students, who certainly see education and a diploma as important tangible benefits they can gain from higher education.

Sociology Making a Difference

Big-Box Stores and the McDonaldization of Society

In many towns across the country during the last decade or so, activists have opposed the building of Wal-Mart and other “big-box” stores. They have had many reasons for doing so: the stores hurt local businesses; they do not treat their workers well; they are environmentally unfriendly. No doubt some activists also think the stores are all the same and are a sign of a distressing trend in the retail world.

Sociologist George Ritzer (2008) coined the term McDonaldization to describe the trend of maximizing productivity and profit by making processes, products, and services identical in certain kinds of utilitarian organizations, such as fast-food franchises. His insights help us understand its advantages and disadvantages and thus help us to evaluate the arguments of big-box critics and the counterarguments of their proponents.

You have certainly eaten, probably too many times, at McDonald’s, Burger King, Subway, KFC, and other fast-food restaurants. Ritzer says that these establishments share several characteristics that account for their popularity but that also represent a disturbing trend.

First, the food at all McDonald’s restaurants is the same, as is the food at all Burger King restaurants or at any other fast-food chain. If you go to McDonald’s in Maine, you can be very sure that you will find the same food that you would find at a McDonald’s in Saginaw or on the other side of the country. You can also be sure that the food will taste the same, even though the two McDonald’s are in different parts of the country. Ritzer uses the terms predictability and uniformity to refer to this similarity of McDonald’s restaurants across the country.

Second, at any McDonald’s the food is exactly the same size and weight. Before it was cooked, the burger you just bought was the same size and weight as the burger the person in front of you bought. This ensures that all McDonald’s customers receive identical value for their money. Ritzer calls this identical measurement of food calculability.

Third, McDonald’s and other restaurants like it are fast. They are fast because they are efficient. As your order is taken, it is often already waiting for you while keeping warm. Moreover, everyone working at McDonald’s has a specific role to play, and this division of labor contributes to the efficiency of McDonald’s, as Ritzer characterized its operations.

Fourth and last, McDonald’s is automated as much as possible. Machines help McDonald’s employees make and serve shakes, fries, and the other food. If McDonald’s could use a robot to cook its burgers and fries, it probably would.

To Ritzer, McDonald’s is a metaphor for the over-rationalization of society, and he cautions that the McDonaldization of society, as he calls it, is occurring. This means that society is becoming increasingly uniform, predictable, calculable, efficient, and automated beyond the fast-food industry. For example, just 50 years ago there were no shopping malls and few national chain stores other than Sears and JCPenney. Then we moved to country-wide shopping malls with a lot of the same stores, and now many of those are closing as Amazon and Walmart further McDonaldization processes.

This uniformity has its advantages. For example, if you are traveling and enter a McDonald’s or Walmart you already know exactly what you will find and probably even where to find it. But uniformity also has its disadvantages. To take just one problem, the national chains have driven out small, locally owned businesses that are apt to offer more personal attention. And if you want to buy a product that a national chain does not carry, it might be difficult to find.

The McDonaldization of society, then, has come at a cost of originality and creativity. Ritzer says that we have paid a price for our devotion to uniformity, calculability, efficiency, and automation. Like Max Weber before him, he fears that the increasing rationalization of society will deprive us of human individuality and also reduce the diversity of our material culture. What do you think? Does his analysis change what you thought about fast-food restaurants and big-box stores?

In contrast, normative organizations (also called voluntary organizations or voluntary associations) allow people to pursue their moral goals and commitments through voluntary joining and showing membership support. Their members do not get paid and instead contribute their time or money because they like or admire what the organization does. The many examples of normative organizations include churches and synagogues, Boy and Girl Scouts, the Kiwanis Club and other civic groups, and groups with political objectives, such as the National Council of La Raza, the largest advocacy organization for Latino civil rights. Alexis de Tocqueville (1835/1994) observed some 175 years ago that the United States was a nation of joiners, and contemporary research finds that Americans indeed rank above average among democratic nations in membership in voluntary associations (Curtis, Baer, & Grabb, 2001).

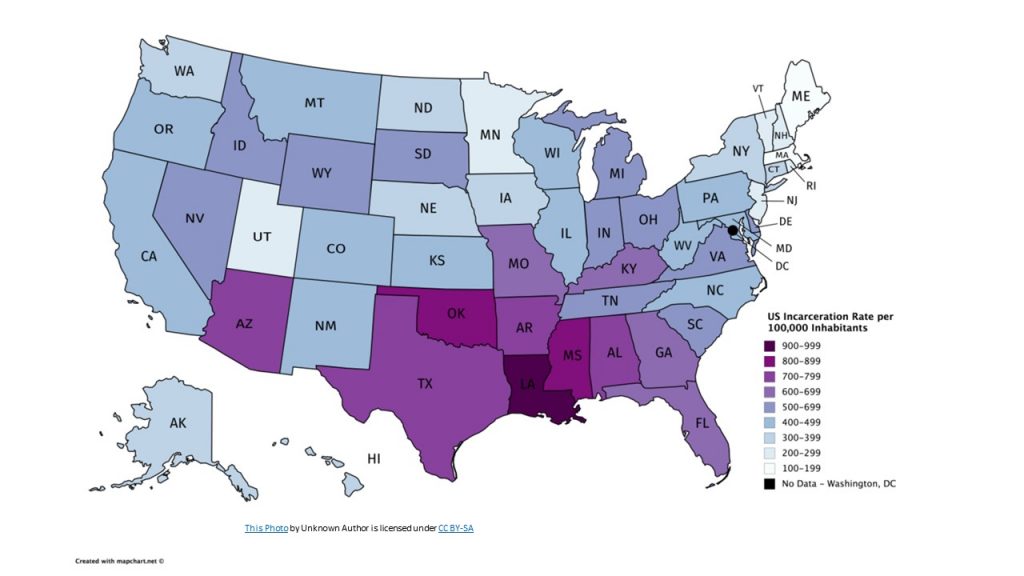

Some people end up in coercive organizations involuntarily because they have violated the law or been judged to be mentally ill. Prisons and state mental institutions are examples of these organizations, which are total institutions that seek to control all phases of their members’ lives. Our chances of ending up in coercive organizations depend on various aspects of our social backgrounds. For prisons one of these aspects is geographical. Figure 6.4 Imprisonment Rate of Sentenced Prisoners under Jurisdiction of State Correctional Authorities per 100,000 U.S. Residents, Age 18 or Older. examines the distribution of imprisonment in the United States and shows the imprisonment rate (number of inmates per 100,000 residents) for each of the four major census regions. This rate tends to be highest in the South and in the West. Do you think this pattern exists because crime rates are highest in these regions or instead because these regions are more likely than other parts of the United States to send convicted criminals to prisons?

Figure 6.4 Imprisonment Rate of Sentenced Prisoners under Jurisdiction of State Correctional Authorities per 100,000 U.S. Residents, Age 18 or Older.

Bureaucracies: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

As discussed earlier, Max Weber emphasized that modern societies increasingly depend on formal organizations to accomplish key tasks. He particularly had in mind bureaucracies, or formal organizations with certain organizational features designed to achieve goals in the most efficient way possible. He said that the ideal type of bureaucracy is characterized by several features listed below that together maximize the efficiency and effectiveness of organizational decision making and goal accomplishment.

- Specialization – By specialization Weber meant a division of labor in which specific people have certain tasks—and only those tasks—to do. Presumably they are most skilled at these tasks and less skilled at others. With such specialization, the people who are best suited to do various tasks are the ones who work on them, maximizing the ability of the organization to have these tasks accomplished.

- Hierarchy – Equality does not exist in a bureaucracy. Instead its structure resembles a pyramid, with a few positions at the top and many more lower down. The chain of command runs from the top to the bottom, with the persons occupying the positions at the top supervising those below them. The higher you are in the hierarchy, the fewer people to whom you have to report. Weber thought a hierarchical structure maximizes efficiency because it reduces decision-making time and puts the authority to make the most important decisions in the hands of the people at the top of the pyramid who presumably are the best qualified to make them.

- Written rules and regulations – For an organization to work efficiently, everyone must know what to do and when to do it. This means their actions must be predictable. To ensure predictability, their roles and the organization’s operating procedures must be written in a manual or handbook, with everyone in the organization expected to be familiar with its rules. Much of the communication among members of bureaucracies is written in the form of memos and e-mail rather than being verbal. This written communication leaves a paper trail so that accountability for individual behavior can later be determined.

- Impartiality and impersonality – The head of a small, non-bureaucratic organization might prefer to hire people she or he knows and promote them on the same basis. Weber thought that impartiality in hiring, promotion, and firing would be much better for a large organization, as it guarantees people will advance through a firm based on their skills and knowledge, not on whom they know. Clients should also be treated impersonally, as an organization in the long run would be less effective if it gave favorable treatment to clients based on whom they know or on their nice personalities. As Weber recognized, the danger is that employees and clients alike become treated like numbers or cogs in a machine, with their individual needs and circumstances ignored in the name of organizational efficiency.

- Record keeping – As you probably know from personal experience, bureaucracies keep all kinds of records, especially in today’s computer age. A small enterprise, say a Mom-and-Pop store, might keep track of its merchandise and the bills its customers owe with some notes scribbled here and there, even in the information technology age, but a large organization must have much more extensive record keeping to keep track of everything.

The Disadvantages of Bureaucracy

Taking all of these features into account, Weber (1921/1978) thought bureaucracies were the most efficient and effective type of organization in a large, complex society. At the same time, he despaired over their impersonality, which he saw reflecting the growing dehumanization that accompanies growing societies. As social scientists have found since his time, bureaucracies have other problems that undermine their efficiency and effectiveness:

- Impersonality and alienation – The first problem is the one just mentioned: bureaucracies can be very alienating experiences for their employees and clients alike. A worker without any sick leave left who needs to take some time off to care for a sick child might find a supervisor saying no, because the rules prohibit it. A client who stands in a long line might find herself turned away when she gets to the front because she forgot to fill out every single box in a form. We all have stories of impersonal, alienating experiences in today’s large bureaucracies.

- Red tape – A second disadvantage of bureaucracy is “red tape,” or, as sociologist Robert Merton (1968) called it, bureaucratic ritualism, a greater devotion to rules and regulations than to organizational goals. Bureaucracies often operate by slavish attention to even the pickiest of rules and regulations. If every t isn’t crossed and every i isn’t dotted, then someone gets into trouble, and perhaps a client is not served. Such bureaucratic ritualism contributes to the alienation already described.

- Trained incapacity – If an overabundance of rules and regulations and overattention to them lead to bureaucratic ritualism, they also lead to an inability of people in an organization to think creatively and to act independently. In the late 1800s, Thorstein Veblen (1899/1953) called this problem trained incapacity. When unforeseen problems arise, trained incapacity may prevent organizational members from being able to handle them.

- Bureaucratic incompetence – Two popular writers have humorously pointed to special problems in bureaucracies that undermine their effectiveness. The first of these, popularly known as Parkinson’s law after its coiner, English historian C. Northcote Parkinson (1957), says that work expands to fill the time available for it. To put it another way, the more time you have to do something, the longer it takes. The second problem is called the Peter Principle, also named after its founder, Canadian author Laurence J. Peter (1969), and says that people will eventually be promoted to their level of incompetence. In this way of thinking, someone who does a good job will get promoted and then get promoted again if she or he continues doing a good job. Eventually such people will be promoted to a job for which they are not well qualified, impeding organizational efficiency and effectiveness. Have you ever worked for someone who illustrated the Peter Principle?

- Goal displacement and self-perpetuation – Sometimes bureaucracies become so swollen with rules and personnel that they take on a life of their own and lose sight of the goals they were originally designed to achieve. People in the bureaucracy become more concerned with their job comfort and security than with helping the organization accomplish its objectives. To the extent this happens, the bureaucracy’s efficiency and effectiveness are again weakened.

Michels’s Iron Law of Oligarchy

Several decades ago Robert Michels (1876–1936), a German activist and scholar, published his famous iron law of oligarchy, by which he meant that large organizations inevitably develop an oligarchy, or the undemocratic rule of many people by just a few people (Michels, 1911/1949). He said this happens as leaders increasingly monopolize knowledge because they have more access than do other organizational members to information and technology. They begin to think they are better suited than other people to lead their organizations, and they also do their best to stay in their positions of power, which they find very appealing. Staying in power becomes more important than helping the organization achieve its objectives and than serving the interests of the workers further down the organizational pyramid. Drawing on our earlier discussion of group size, it is also true that as an organization becomes larger, it becomes very difficult to continue to involve all group members in decision making, which almost inevitably becomes monopolized by the relatively few people at the top of the organization. Michels thought oligarchization happens not only in bureaucracies but also in a society’s political structures, and he said that the inevitable tendency to oligarchy threatens democracy by concentrating political decision-making power in the hands of a few. As his use of the term iron law suggests, Michels thought the development of oligarchies was inevitable, and he was very pessimistic about democracy’s future.

Gender, Race, and Formal Organizations

We previously outlined three types of organizations: utilitarian, normative, and coercive. What does the evidence indicate about the dynamics of gender and race in these organizations?

Women in utilitarian organizations such as businesses have made striking inroads but remain thwarted by a glass ceiling and the refusal of some subordinates to accept their authority. The workforce as a whole remains segregated by sex, as many women are more concentrated in some occupations such as clerical and secretarial work. Gendered career concentrations contribute to the lower pay that women receive compared to men. Turning to race, federal and state laws against racial discrimination in the workplace arose in the aftermath of the civil rights movement of the 1960s. While anti-discrimination laws apply to the workplace and have resulted in hiring, promotion, and salary protections for white women and people of color, the laws have narrowed the wage gap, they have not erased it.

Learning From Other Societies

Japan’s Formal Organizations: Benefits and Disadvantages of Traditional Ways

Although Japan possesses one of the world’s most productive industrial economies, its culture remains very traditional in several ways. For example, the Japanese culture continues to value harmony and cooperation and to frown on public kissing. Interestingly, Japan’s traditional ways are reflected in its formal (utilitarian) organizations even as they contribute to the global production of cars, electronics, and other products and provide some lessons for our own society.

Consider the experiences of women in the Japanese workplace, as this experience reflects Japan’s very traditional views on women’s social roles (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). Japan continues to think a woman’s place is first and foremost in the home and with her children. Accordingly, women there have far fewer job opportunities than do men and often have few job prospects beyond clerical work and other blue-collar positions. Many young women seek to become “office ladies,” whose main role in a business is to look pretty, do some filing and photocopying, and be friendly to visitors. They are supposed to live at home before marrying and typically must quit their jobs when they do marry. Women occupy only about 10% of managerial positions in Japan’s business and government, compared to 43% of their U.S. counterparts (Fackler, 2007).

For these reasons, men are the primary subjects of studies on life in Japanese corporations. Here we see some striking differences from how U.S. corporations operate (Jackson & Tomioka, 2004). For example, the emphasis on the group in Japanese schools also characterizes corporate life. Individuals hired at roughly the same time by a Japanese corporation are evaluated and promoted collectively, not individually, although some corporations have tried to conduct more individual assessment. Just as Japanese schools have their children engage in certain activities to foster group spirit, so do Japanese corporations have their workers engage in group exercises and other activities to foster a community feeling in the workplace. The companies sponsor many recreational activities outside the workplace for the same reason. In another difference from their American counterparts, Japanese companies have their workers learn several different jobs within the same companies so that they can discover how the various jobs relate to each other. Perhaps most important, leadership in Japanese corporations is more democratic and less authoritarian than in their American counterparts. Japanese workers meet at least weekly in small groups to discuss various aspects of their jobs and of corporate goals and to give their input to corporate managers.

Japan’s traditional organizational culture, then, has certain benefits but also one very important disadvantage, at least from an American perspective (Levin, 2006). Its traditional, group-oriented model seems to generate higher productivity and morale than the more individualistic American model. On the other hand, its exclusion of women from positions above the clerical level deprives Japanese corporations of women’s knowledge and talents and would likely frustrate many Americans. As the United States tries to boost its own economy, it may well make sense to adopt some elements of Japan’s traditional organizational model, as some U.S. information technology companies have done, but there would be resistance to incorporating its views of women and the workplace.

Much less research exists on gender and race in normative organizations. But we do know that many women are involved in many types of these voluntary associations, especially those having to do with children and education and related matters. These associations allow them to contribute to society and are a source of self-esteem and, more practically, networking (Blackstone, 2004; Daniels, 1988). Many people of color have also been involved in normative organizations, especially those serving various needs of their communities. One significant type of normative organization is the church, which has been extraordinarily important in the Black community over the decades and was a key locus of civil rights activism in the South during the 1960s (Morris, 1984).

Turning to coercive organizations, we know much about prisons and the race and gender composition of their inmates. Men, Black people, and Latinos are overrepresented in prisons and jails. This means that they constitute much higher percentages of all inmates than their numbers in the national population would suggest. Although men make up about 50% of the national population, for example, they account for more than 90% of all prisoners. Similarly, although Black people are about 13% of the population, they account for more than 40% of all prisoners. The corresponding percentages for Latinos are about 15% and almost 20%, respectively (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2010). Formal organizations, particularly coercive organizations, are a focus of the next chapter.

6.4 End-of-Chapter Material

- Social groups are the building blocks of social life, and it is virtually impossible to imagine a society without groups and difficult to imagine individuals not being involved with many types of groups. They are distinguished from social categories and social aggregates by the degree of interaction among their members and the identification of their members with the group.

- Primary groups are small and involve strong emotional attachments, while secondary groups are larger and more impersonal. Some groups become in-groups and vie, sometimes hostilely, with people they identify as belonging to out-groups. Reference groups provide standards by which we judge our attitudes and behavior and can influence how we think and act.

- Social networks connect us through the people we know to other people they know. They are increasingly influential for successful employment but are also helpful for high-quality health care and other social advantages.

- The size of groups is a critical variable for their internal dynamics. Compared to large groups, small groups involve more intense emotional bonds but are also more unstable. These differences stem from the larger number of relationships that can exist in a larger group than in a smaller one.

- Processes of group conformity are essential for any society and for the well-being of its many individuals but also can lead to reprehensible norms and values. People can be influenced by their group membership and the roles they’re expected to play to engage in behaviors most of us would condemn. Laboratory experiments by Asch and Milgram illustrate how this can happen.

- Formal organizations include utilitarian, normative and coercive models.

- The benefits of McDonanldization include predictability and uniformity, calculability, efficiency, and automation, but the costs are creativity and innovation.

- As one type of formal organization, the bureaucracy has several defining characteristics, including specialization, hierarchy, written rules and regulations, impartiality and impersonality, and record keeping. Risks included impersonality and alienation, red tape, trained incapacity, bureaucratic incompetence, and goal displacement and self preservation.

- Robert Michels hypothesized that the development of oligarchies in formal organizations and political structures is inevitable. History shows that such “oligarchization” does occur in utilitarian and political spheres.