7

Chapter Learning Outcomes

- Define deviance, understand what is meant by the relativity of deviance and discuss the role sanctions play in conformity.

- Compare and contrast the major sociological perspectives on deviance and their respective theories.

- Understand the relationship between obedience, conformity and social control.

- Explain the relationships between demographic characteristics and stigmatization, stereotyping and scapegoating, as they are related to deviance.

7.1 Social Control and the Relativity of Deviance

Deviance is any behavior that violates social norms and often arouses negative social reactions. Deviance ranges from something as simple as picking one’s nose to behavior that are considered so harmful that governments enact written laws that ban the behavior, such as rape and murder. Crime is behavior that violates these laws and is certainly an important type of deviance that concerns many Americans.

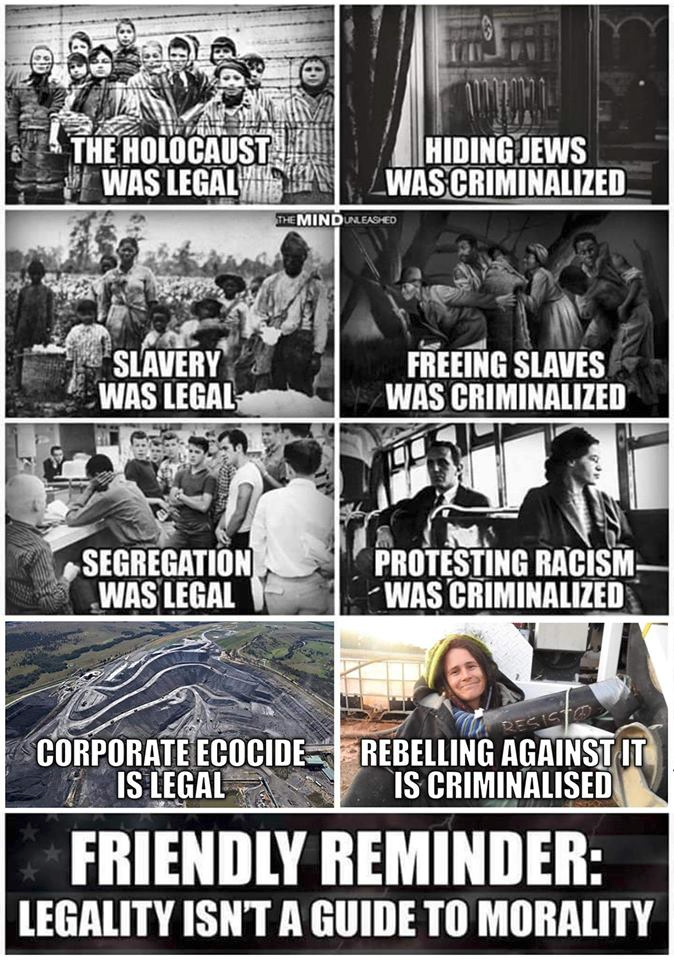

“Although the word “deviance” has a negative connotation in everyday language, sociologists recognize that deviance is not necessarily bad (Schoepflin 2011). In fact, from a structural functionalist perspective, one of the positive contributions of deviance is that it fosters social change. For example, during the U.S. civil rights movement, Rosa Parks violated social norms by refusing to give up her seat to a white man, and the Little Rock Nine broke customs of segregation to attend an Arkansas public school (Openstax SOC 2e).” Social control refers to ways in which a society tries to prevent and sanction deviant behavior and other attempts at compelling conformity. Just as a society like the United States has informal and formal norms, so does it have informal and formal social control. Generally, informal social control is used to control behavior that violates informal norms (or folkways), and formal social control is used to control behavior that violates formal norms (or mores). We typically conform to informal norms because we fear risking the negative reactions of other people. These reactions, and thus examples of informal social control, include anger, disappointment, ostracism, and ridicule. Formal social control in the United States typically involves the legal system (police, judges and prosecutors, corrections officials) and also, for businesses, the many local, state, and federal regulatory agencies that constitute the regulatory system.

Social control is never perfect, and so many norms and people exist that we all violate some norms. For example, if you speed you violate a formal norm, but if you don’t speed in our home state of Michigan, then there are likely 10 cars angrily lined up behind you because you are violating the informal norm in Michigan that says you push the speed limit by 5. Both of these violations of norms, one formal and one informal, are deviant. It is also important to note that those with power define the criminally deviant as what other (poor) people do, while giving their own deviance legitimacy. A perfect example of how this plays out in an unfair manner is to compare the use of cocaine and escorts to the use crack and street prostitution. One (cocaine and escorts) gets you rehab and publicity, the other (crack and street prostitution) gets you incarcerated.

Émile Durkheim (1895/1962), stressed that a society without deviance is impossible for at least two reasons. First, the collective conscience is never strong enough to prevent all rule breaking. Even in a “society of saints,” such as a monastery, he said, rules will be broken and negative social reactions aroused. Second, deviance serves several important functions for society, which are discussed later in this chapter. Because Durkheim thought deviance was inevitable for these reasons, he considered it a normal part of every healthy society.

Although deviance is normal in this regard, it remains true that some people are more likely than others to commit it. It is also true that some locations within a given society have higher rates of deviance than other locations; for example, U.S. cities have higher rates of violent crime than do rural areas. It is also important to understand that deviance is socially constructed, meaning definitions of deviance are created by society. In other words deviance is relative. Durkheim’s monastery example demonstrates the relativity of deviance: whether a behavior is considered deviant depends on the circumstances in which the behavior occurs and not on the behavior itself. Although talking might be considered deviant in a monastery, it would certainly be considered very normal elsewhere. If an assailant, say a young male, murders someone, he faces arrest, prosecution, and, in many states, possible execution. Yet if a soldier kills someone in wartime, he may be considered a hero. Killing occurs in either situation, but the context and reasons for the killing determine whether the killer is punished or given a medal.

Deviance is also relative in two other ways. First, it is relative in space: a given behavior may be considered deviant in one society but acceptable in another society. For example, sexual acts condemned in some societies are often practiced in others. Second, deviance is relative in time: a behavior in a given society may be considered deviant in one time period but acceptable many years later, and vice versa. In the late 1800s, many Americans used cocaine, marijuana, and opium, because they were common components of over-the-counter products for symptoms like depression, insomnia, menstrual cramps, migraines, and toothaches. Coca-Cola originally contained cocaine and, perhaps not surprisingly, became an instant hit when it went on sale in 1894 (Goode, 2008). Today, of course, these drugs are illegal in most states. The relativity of deviance in all these ways is captured in a famous statement by sociologist Howard S. Becker (1963, p. 9), who wrote several decades ago that: deviance is not a quality of the act the person commits, but rather a consequence of the application by others of rules or sanctions to an “offender.” The deviant is one to whom that label has been successfully applied; deviant behavior is behavior that people so label.

This insight raises some provocative possibilities for society’s response to deviance. First, harmful behavior committed by corporations and wealthy individuals may not be considered deviant, perhaps because “respectable” people engage in them. Second, prostitution and other arguably less harmful behaviors may be considered very deviant because they are deemed immoral or because of bias against the kinds of people (i.e., poor) thought to be engaging in them. These considerations yield several questions that need to be answered in the study of deviance. First, why are some individuals more likely than others to commit deviance? Second, why do rates of deviance differ within social categories such as gender, race, social class, and age? Third, why are some locations more likely than other locations to have higher rates of deviance? Fourth, why are some behaviors more likely than others to be considered deviant? Fifth, why are some individuals and those from certain social backgrounds more likely than other individuals to be considered deviant and punished for deviant behavior? Sixth and last but certainly not least, what can be done to reduce rates of violent crime and other serious forms of deviance? The sociological study of deviance and crime aims to answer all of these questions.

7.2 Explaining Deviance

If we want to reduce violent crime and other serious deviance, we must first understand why it occurs. Many sociological theories of deviance exist, and together they offer a more complete understanding of deviance than any one theory offers by itself. Together they help answer the questions posed earlier: why rates of deviance differ within social categories and across locations, why some behaviors are more likely than others to be considered deviant, and why some kinds of people are more likely than others to be considered deviant and to be punished for deviant behavior. As a whole, sociological explanations of deviance highlight the importance of social inequality, the social environment and social interaction. As such, they have important implications for how to reduce these behaviors. We now turn to the major sociological explanations of crime and deviance, summarized below.

Table 7.1 Theory Snapshot: Summary of Sociological Explanations of Deviance and Crime

| Theoretical Perspective | Theory | Summary of Theory |

| Functionalist Perspective | Durkheim’s Anomie Theory | Deviance serves a purpose by clarifying norms, strengthening social bonds among people reacting to deviance and deviance can lead to positive social change. |

| Merton’s Structural Strain | Deviance results from the gap between the cultural emphasis on economic success and the inability to achieve such success through legitimate means by some individuals or groups. | |

| Differential Opportunity | Different social classes have distinct patterns of crime due to differential access to institutionalized means. | |

| Conflict Perspective | Differential Justice | People with power use the legal system to secure their position at the top of society and to keep the powerless at the bottom. The poor and minorities are more likely, because of their lower status, to be arrested, convicted and imprisoned. |

| Feminist | Gender inequality, sexism and antiquated views about relationships between the sexes underlie sexual assault, rape, intimate partner violence, and other crimes against women. | |

| Interactionist Perspective | Differential Association | Criminal behavior is learned by interacting with close friends and family members who teach us how to commit crimes and also about values, motives and rationalizations we need to adopt in order to justify breaking the law. |

| Social Control | Deviance results from weak bonds to conventional social institutions and social groups, as well as a lack of internalization of expected cultural norms. | |

| Labeling | Deviance results from being labeled a deviant. |

Functionalist Explanations

Several explanations may be grouped under the functionalist perspective in sociology, as they all share this perspective’s central view on the importance of various aspects of society for social stability and control.

Émile Durkheim: The Functions of Deviance

As noted earlier, Émile Durkheim said deviance is normal, but he did not stop there. In a surprising and still controversial twist, he also argued that deviance serves several important functions. First, Durkheim said, deviance clarifies social norms and increases conformity. This happens because the discovery and punishment of deviance reminds people of the norms and reinforces the consequences of violating them. If your class were taking an exam and a student was caught cheating, the rest of the class would be instantly reminded of the rules about cheating and the punishment for it, and as a result they would be less likely to cheat.

A second function of deviance is that it strengthens social bonds among the people reacting to the deviant. An example comes from the classic story The Ox-Bow Incident (Clark, 1940), in which three innocent men are accused of cattle rustling and are eventually lynched. The mob that does the lynching is very united in its frenzy against the men, and, at least at that moment, the bonds among the individuals in the mob are extremely strong.

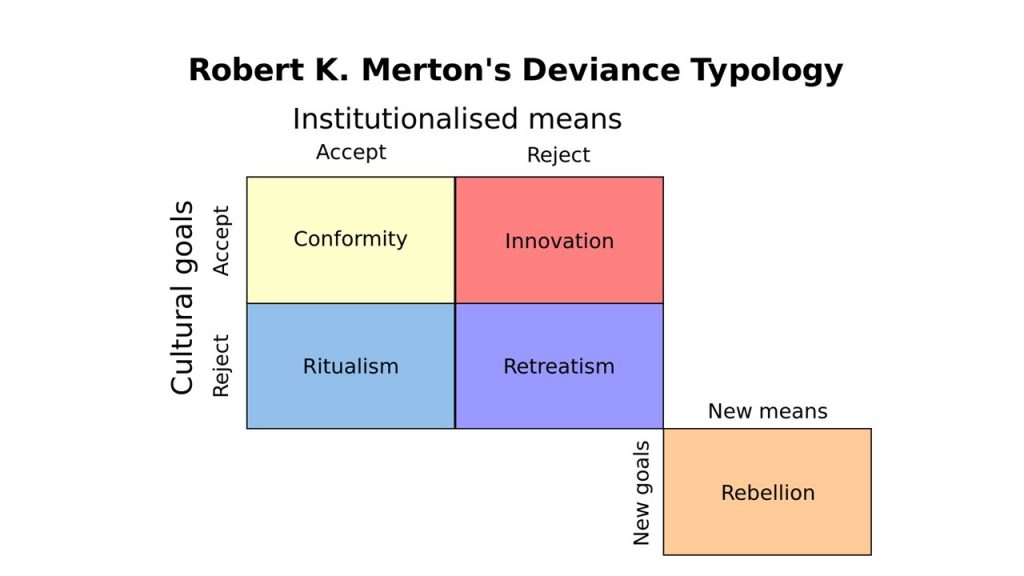

A final function of deviance, said Durkheim, is that it can help lead to positive social change. Although some of the greatest figures in history—Socrates, Jesus, Joan of Arc, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr. to name just a few—were considered the worst kind of deviants in their time, we now honor them for their commitment and sacrifice.

Sociologist Herbert Gans (1996) pointed to an additional function of deviance: deviance creates jobs for the segments of society—police, prison guards, criminology professors, and so forth—whose main focus is to deal with deviants in some manner. If deviance and crime did not exist, hundreds of thousands of law-abiding people in the United States would be out of work!

Although deviance can have all of these functions, many forms of it can certainly be quite harmful, as the story of the mugged voter that began this chapter reminds us. Violent crime and property crime in the United States victimize millions of people and households each year, while crime by corporations has effects that are even more harmful and far reaching, as we discuss later. Drug use, prostitution, and other “victimless” crimes may involve willing participants, but these participants often cause themselves and others much harm. Although deviance, according to Durkheim, is inevitable and normal and serves important functions, that certainly does not mean any national should be content to have high rates of serious deviance. The sociological theories we discuss point to certain aspects of the social environment, broadly defined, that contribute to deviance and crime and that should be the focus of efforts to reduce these behaviors.

Strain Theory

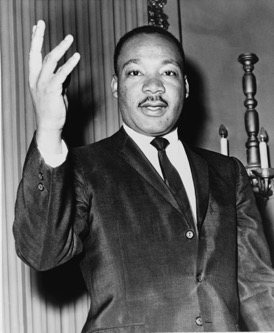

Failure to achieve the American dream lies at the heart of Robert Merton’s (1938) famous strain theory. You may recall, Durkheim attributed high rates of suicide to anomie, or normlessness, that occurs in time when social norms are unclear or weak. Adapting this concept, Merton wanted to explain why poor people have higher deviance rates than the non-poor. He reasoned that the U.S. values economic success above all else and also have norms that specific the approved means for achieving economic success. Because the poor often cannot achieve the American dream of success through the conventional means of achieving higher education and working, they experience a gap between the goal of economic success and the means of achieving this goal. This gap leads to strain or frustration. To reduce their frustration, some people resort to several adaptations, including deviance, depending on whether they accept or reject the goal of economic success and/or the means of achieving the goals. Figure 7.1 “Merton’s Structural Strain Theory Deviance Typology” present the logical adaptations of individuals to the strain they experience. Let’s review these briefly.

Figure 7.1 Merton’s Structural Strain Theory

Faced with strain, some people continue to value economic success but come up with new means of achieving it. They rob people or banks, sell illegal drugs, commit fraud or use other illegal means of acquiring money or property. Merton calls this adaptation innovation. Despite experiencing strain, most people continue to accept the goal of economic success and continue to believe they should work to make money. In other words, they continue to conform to the cultural norms and remain good, law-abiding citizens. Merton calls their adaptation, conformity.

Other people continue to work at a job without much hope of greatly improving their lot in life. They go to work day after day as a habit, even when they no longer accept the goal of economic success. Merton calls this third adaptation ritualism. This adaptation does not involve deviant behavior but is a logical response to the strain people experience.

In Merton’s fourth adaptation, retreatism, some people withdraw from society by isolating themselves, becoming vagrants or by becoming addicted to alcohol, heroin, or other drugs. Their response to the strain they feel is to reject both the goal of economic success and the means of achieving the goal.

Merton’s fifth and final adaptation is rebellion. Here people not only reject the goal of success and the means of achieving the goal, but work actively to bring about a new society with a new value system. These people are the radicals and revolutionaries of their time. Because Merton developed his strain theory in the aftermath of the Great Depression, in which the labor and socialist movements had been quite active, it is not surprising that he thought of rebellion as a logical adaptation of the poor to their lack of economic success.

Although Merton’s theory has been popular over the years, it has some limitations. Perhaps most important, it overlooks deviance such as fraud by the middle and upper classes and also fails to explain murder, rape, and other crimes that usually are not done for economic reasons. It also does not explain why some people choose one adaptation over another.

Merton’s strain theory stimulated other explanations of deviance that built on his concept of strain. Differential opportunity theory, developed by Richard Cloward and Lloyd Ohlin (1960), tried to explain why the poor choose one or the other of Merton’s adaptations. Whereas Merton stressed that the poor have differential access to legitimate means (working), Cloward and Ohlin stressed that they also have differential access to illegitimate means. For example, some people live in neighborhoods where organized crime is dominant and will get involved in such crime; others live in neighborhoods rampant with drug use and will start using drugs themselves.

In a more recent formulation, two sociologists, Steven F. Messner and Richard Rosenfeld (2007), expanded Merton’s view by arguing that in the United States crime arises from several of our most important values, including an overemphasis on economic success, individualism, and competition. These values produce crime by making many Americans, rich or poor, feel they never have enough money and by prompting them to help themselves even at other people’s expense. Crime in the United States, then, arises ironically from the country’s most basic values.

A critique of Merton’s strain theory, differential opportunity theory, and Messner and Rosenfeld’s theories are that they do not explain why middle class and wealthy people commit acts of deviance and they do not explain white collar crime.

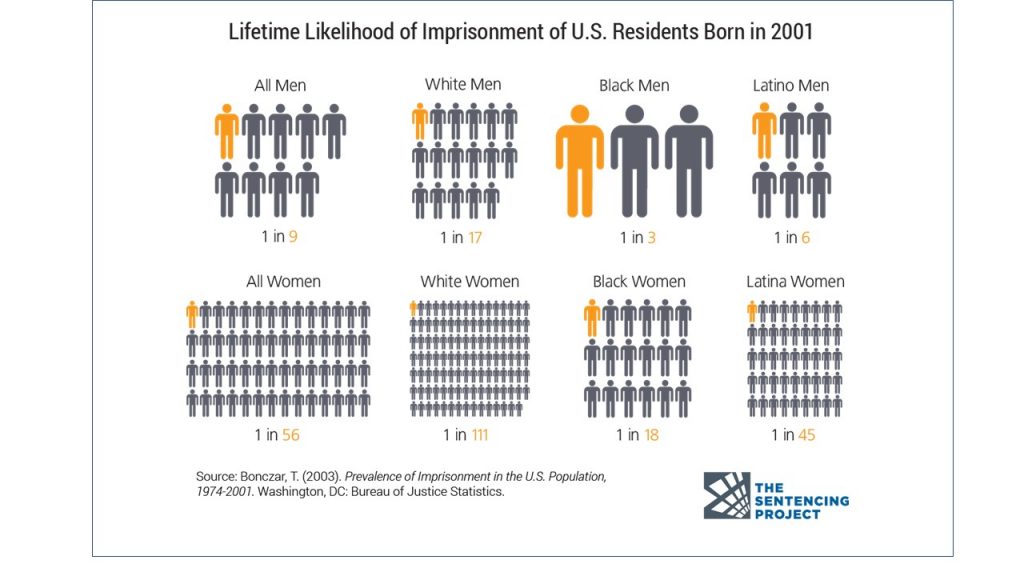

Conflict Perspective: Differential Justice

Explanations of crime rooted in the conflict perspective reflect its general view that society is a struggle between the “haves” at the top of society with social, economic, and political power and the “have-nots” at the bottom. Accordingly, they assume that those with power pass laws and otherwise use the legal system to secure their position at the top of society and to keep the powerless on the bottom (Bohm & Vogel, 2011). The poor and minorities are more likely because of their poverty and race to be arrested, convicted, and imprisoned. These explanations also blame street crime by the poor on the economic deprivation and inequality in which they live rather than on any moral failings of the poor.

Moreover, in the theory of differential justice, theorists argue that elite deviants can hide their crimes and avoid criminal labels due to the power and resources they have at their disposal. In contrast, the criminal justice system directs its energies against violations by the working class and low-income individuals have little power and ability to counteract these efforts. Ultimately, the law and criminal justice system work to protect the interests of the dominant class and regulates populations perceived as posing a threat to the interests of the affluent.

Not surprisingly, conflict explanations have sparked much controversy (Akers & Sellers, 2008). Many scholars dismiss them for painting an overly critical picture of capitalist economies and ignoring the excesses of non-capitalistic nations, while others say the theories overstate the degree of inequality in the legal system. However, much evidence supports the conflict assertion that the poor and minorities face disadvantages in the legal system (Reiman & Leighton, 2010). Simply put, the poor cannot afford good attorneys, private investigators, and the other advantages that money brings in court. Also in accordance with the conflict perspective’s views, corporate executives, among the most powerful members of society, often break the law without fear of imprisonment, as we shall see in our discussion of white-collar crime later in this chapter. Finally, many studies support conflict perspective’s view that the roots of crimes by poor people lie in social inequality and economic deprivation (Barkan, 2009).

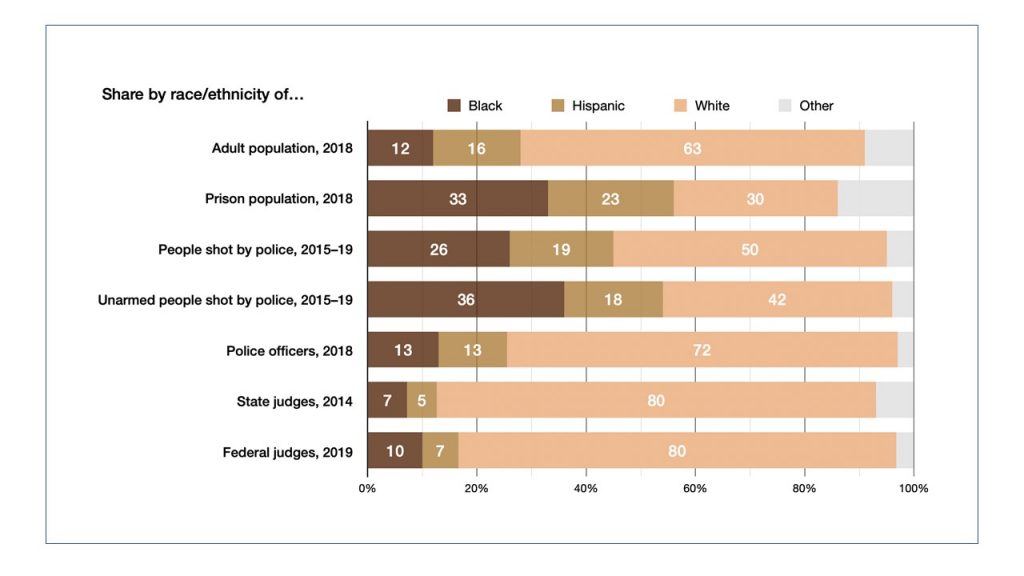

Figure 7.2 Race Disparities in US Criminal Justice System, Late 2010s

Feminist Perspectives

Feminist perspectives on crime and criminal justice also fall into the broad rubric of conflict explanations and have burgeoned in recent decades. Much of this work concerns rape and sexual assault, intimate partner violence and other crimes against women that were largely neglected until feminists began writing about them in the 1970s (Griffin, 1971). Their views have since influenced public and official attitudes about rape and domestic violence, which used to be thought as something that girls and women brought on themselves. The feminist approach instead places the blame for these crimes squarely on society’s inequality against women and antiquated views about relations between the sexes (Renzetti, 2011).

Another focus of feminist work relates to the arrest and legal processing of females for crimes associated with their attempts to escape domestic violence and other forms of abuse. Research studies on incarcerated females have found that the victimization experienced by these girls and women is often linked with their entry into the criminal justice system (Gilfus, 2002). For instance, if a girl runs away from home due to sexual abuse, and, lacking support, commits petty theft or an act of prostitution, she may be prosecuted for these crimes. Given that the crimes committed result for the circumstances associated with her abuse, in such a case, feminists ask, what penalty should she face?

A third focus concerns the gender difference in serious crime, as women and girls are much less likely than men and boys to engage in violence and to commit serious property crimes such as burglary and motor vehicle theft. Most sociologists attribute this difference to gender socialization. Simply put, socialization into the male gender role, or masculinity, leads to values such as competitiveness and behavioral patterns such as spending more time away from home that all promote deviance. Conversely, despite whatever disadvantages it may have, socialization into the female gender role, or femininity, promotes values such as gentleness and behavior patterns such as spending more time at home that help limit deviance (Chesney-Lind & Pasko, 2004). Noting that males commit so much more crime, Kathleen Daly and Meda Chesney-Lind (1988, p. 527) wrote,

“A large price is paid for structures of male domination and for the very qualities that drive men to be successful, to control others, and to wield uncompromising power.…Gender differences in crime suggest that crime may not be so normal after all. Such differences challenge us to see that in the lives of women, men have a great deal more to learn. “

Three decades later, that challenge still remains.

Symbolic Interactionist Explanations

Because symbolic interactionism focuses on the means people gain from their social interaction, symbolic interactionist explanations attribute deviance to various aspects of the social interaction and social processes that normal individuals experience. These explanations help us understand why some people are more likely than others living in the same kinds of social environments. Several such explanations exist.

Differential Association Theory

One popular explanation for deviance emphasizes that deviance is learned from interacting with other people who believe it is okay to commit deviance and who often commit deviance themselves. Deviance, then, arises from normal socialization processes. The most influential such explanation is Edwin H. Sutherland’s (1947) differential association theory, which says that criminal behavior is learned by interacting with close friends and family members who are themselves deviant. These individuals teach us not only how to commit various crimes but also the values, motives, and rationalizations that we need to adopt in order to justify breaking the law. The earlier in our life that we associate with deviant individuals and the more often we do so, the more likely we become deviant ourselves. In this way, a normal social process, socialization, can lead once normal people to commit deviance.

Sutherland’s theory of differential association was one of the most influential sociological theories ever. Over the years much research has documented the importance of adolescents’ peer relationships for their entrance into the world of drugs and delinquency (Akers & Sellers, 2008). However, some critics say that not all deviance results from the influences of deviant peers. Still, differential association theory remains a valuable approach to understanding deviance and crime.

Social Control Theory

Travis Hirschi (1969) argued that human nature is basically selfish and thus wondered why people do not commit deviance. His answer, which is called social control theory, was that their bonds to conventional social institutions and social groups, such as the family and schools, keep them from violating social norms.

Hirschi outlined four types of bonds to conventional social institutions: attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.

- Attachment refers to how much we feel loyal to these institutions and care about the opinions of people in them, such as our parents and teachers. The more attached we are to our families and schools, the less likely we are to be deviant.

- Commitment refers to how much we value our participation in conventional activities such as getting a good education. The more committed we are to these activities and the more time and energy we have invested in them, the less deviant we will be.

- Involvement refers to the amount of time we spend in conventional activities. The more time we spend, the less opportunity we have to be deviant.

- Belief refers to our acceptance of society’s norms. The more we believe in these norms, the less we deviate.

Many studies find that youths with weaker bonds to their parents and schools are more likely to be deviant. But the theory has its critics (Akers & Sellers, 2008). One problem centers on the chicken-and-egg question of causal order. For example, many studies support social control theory by finding that delinquent youths often have worse relationships with their parents than do non-delinquent youths. Is that because the bad relationships prompt the youths to be delinquent, as Hirschi thought? Or is it because the youths’ delinquency worsens their relationship with their parents? Despite these questions, Hirschi’s social control theory continues to influence our understanding of deviance. To the extent it is correct, it suggests several strategies for preventing crime, including programs designed to improve parenting and relations between parents and children (Welsh & Farrington, 2007).

Labeling Theory

If we arrest and imprison someone, we hope they will be deterred from committing a crime again. Labeling theory assumes precisely the opposite: it says that labeling someone deviant increases the chances that the labeled person will continue to commit deviance. According to labeling theory, this happens because the labeled person ends up with a deviant self-image that leads to even more deviance. Deviance is the result of being labeled (Bohm & Vogel, 2011). It is important to note that people in positions of power have the authority to make the rules and define deviance. Labels are also not given to everyone in the same manner. People of lower socioeconomic status and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) are more likely to be labeled deviant.

This effect is reinforced by how society treats someone who has been labeled. Research shows that white job applicants with a criminal record are much less likely than white applicants without a record to be hired, but white applicants with a criminal background are more likely than Black applicants with no criminal background (Pager, 2009). Imagine the likelihood of getting hired if you are Black and have a criminal background. Suppose you had a criminal record and had seen the error of your ways but were rejected by several potential employers. Do you think you might be just a little frustrated? If your unemployment continues, might you think about committing a crime again? Meanwhile, you want to meet some law-abiding friends, so you go to a singles bar. You start talking with someone who interests you, and in response to this person’s question, you say you are between jobs. When your companion asks about your last job, you reply that you were in prison for armed robbery. How do you think your companion will react after hearing this? As this scenario suggests, being labeled deviant can make it difficult to avoid a continued life of deviance.

Labeling theory also asks whether some people and behaviors are indeed more likely than others to acquire a deviant label. In particular, it asserts that non-legal factors such as appearance, race, and social class affect how often official labeling occurs. William Chambliss’s (1973) classic analysis of the “Saints” and the “Roughnecks” is an excellent example of this argument. The Saints were eight male high-school students from middle-class backgrounds who were very delinquent, while the Roughnecks were six male students in the same high school who were also very delinquent but who came from poor, working-class families. Although the Saints’ behavior was arguably more harmful than the Roughnecks’, their actions were considered harmless pranks, and they were never arrested. After graduating from high school, they went on to college and graduate and professional school and ended up in respectable careers. In contrast, the Roughnecks were widely viewed as troublemakers and often got into trouble for their behavior. As adults they either ended up in low-paying jobs or went to prison.

Labeling theory postulates that those labeled as deviant, caused one to be deviant. Labeling theory’s views on the effects of being labeled and on the importance of nonlegal factors for official labeling remain controversial. Nonetheless, the theory has greatly influenced the study of deviance and crime in the last few decades and promises to do so for many years to come.

7.3 Crime and Criminals

We now turn our attention from theoretical explanations of deviance and crime to certain aspects of crime and the people who commit it. What do we know about crime and criminals in the United States?

Crime and Public Opinion

One thing we know is that the American public is very concerned about crime. In a 2009 Gallup Poll, about 55% said crime is an “extremely” or “very” serious problem in the United States, and in other national surveys, about one-third of Americans said they would be afraid to walk alone in their neighborhoods at night (Maguire & Pastore, 2009; Saad, 2008).

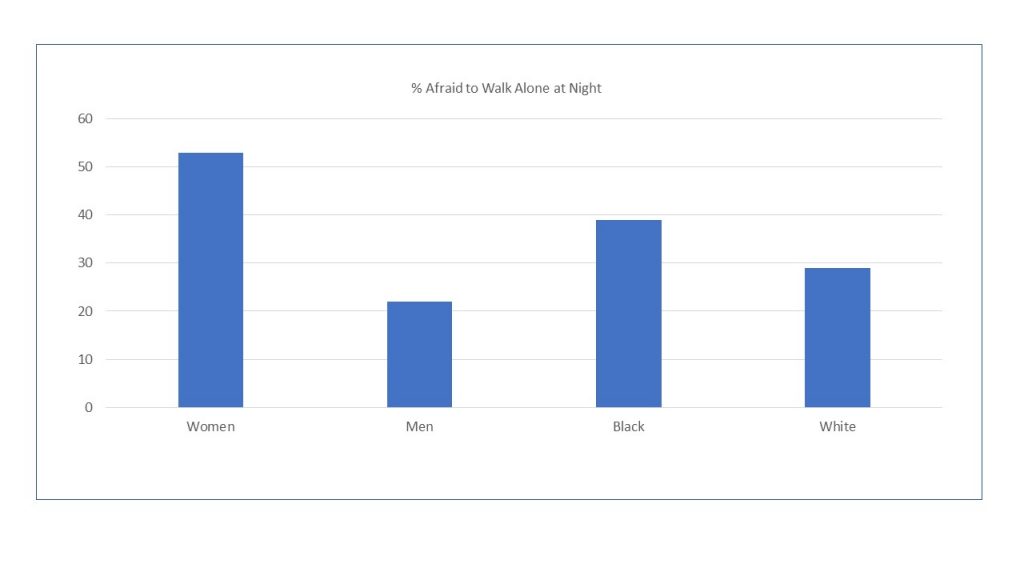

Recall that according to the sociological perspective, our social backgrounds affect our attitudes, behavior, and life chances. Do gender and race affect our fear of crime? Figure 7.3 “Gender, Race and Fear of Crime” shows that both gender and race have quite a large effect. About 53% of women are afraid to walk alone at night, compared to only 22% of men. Because women are less likely than men to be victims of crime other than rape, their higher fear of crime reflects their heightened fear of rape and other types of sexual assault (Warr, 2000). Similarly, race also makes a difference, as shown below. Figure 7.3 “Gender, Race and Fear of Crime” shows that Black people are more afraid than whites of walking near their homes alone at night. This difference reflects the fact that Black people are more likely than whites to live in large cities with higher rates of crime (Peterson & Krivo, 2009).

Figure 7.3 Gender, Race and Fear of Crime

Race also affects views about the criminal justice system. For example, Black people are much less likely than whites to favor the death penalty, in part because they perceive that the death penalty and criminal justice system in general are racially discriminatory (Johnson, 2008).

The Measurement of Crime

It is surprisingly difficult to know how much crime occurs. Usually when crime occurs, only the criminal and the victim, and sometimes an occasional witness, know about it. Although we have an incomplete picture of the crime problem, because of various data sources we still have a fairly good understanding of how much crime exists.

The government’s primary source of crime data is the Uniform Crime Report (UCR), published annually by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The FBI gathers its data from police departments around the country. Most UCR data concerns Part I Offenses, which are the eight felonies that the FBI considers the most serious. Four of these are violent crimes: homicide, rape, aggravated assault, and robbery; four are property crimes: burglary, larceny (e.g., shoplifting, pickpocketing, purse snatching), motor vehicle theft and arson.

According to the FBI, in 2016 almost 1.25 million violent crimes occurred in the U.S., which is the equivalent to 386.3 violent crimes per every 100,000 people. In addition, there were 7.9 million property crimes in 2017, or 2450 property crimes for every 100,000 Americans. This is the nation’s official crime rate, and by any standard it is a lot of crime. Many people in the U.S. perceive that the rate of crime is growing, however, looking at longitudinal data from the FBI shows that the rate of crime is dropping over time, with some annual fluctuation. Table 7.2 “U.S. Crime Rates Over Time” demonstrates this trend. Note that while the population has increased by over 55 million in the last 20 years, the number of crimes have decreased by over 4 million.

Table 7.2 U.S. Crime Rates Over Time

| Year | Population Size | Number of Violent Crime Incidences | Violent Crime Rate * | Number of Property Crime Incidences | Property Crime Rate * |

| 1997 | 267,783,607 | 1,636,096 | 611.0 | 11,558,475 | 4,326.3 |

| 2002 | 287,973,924 | 1,423,677 | 494.4 | 10,455,277 | 3,630.6 |

| 2007 | 301,621,157 | 1,422,970 | 471.8 | 9,882,212 | 3,276.4 |

| 2012 | 313,873,685 | 1,217,057 | 387.8 | 9,001,992 | 2,868.0 |

| 2016 | 323,127,513 | 1,248,185 | 386.3 | 7,919,035 | 2,450.7 |

*Violent Crime and Property Crime Rates show the number of crime victims per every 100,000 in the population

Source: Data from Federal Bureau of Investigations. Retrieved from https:// ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016

However, one thing to keep in mind is that these figures are in fact lower than the actual crime rate because, according to surveys of random samples of crime victims, more than half of all crime victims do not report their crimes to the police, leaving the police unaware of the crimes. For instance, based on data from the National Crime Victims Survey, the Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated that in 2016, only 42.1% of violent crimes were reported to the police and that only 35.7% of property crimes were reported. Underreporting varies by the type of crime. For instance, rapes and sexual assaults were found to be reported to the police only 22.9% of the time, while motor vehicle thefts were reported 79.9% of the time (Morgan & Kena, 2017). Reasons for non-reporting include the belief that police will not be able to find the offender and fear of retaliation by the offender. The true crime problem is therefore greater than suggested by the UCR.

This underreporting of crime represents a major problem for the UCR’s validity. Several other problems exist (Lynch & Addington, 2007). First, the UCR omits crime by corporations and thus diverts attention away from their harm (see a little later in this chapter). Second, police practices affect the UCR. For example, the police do not record every report they hear from a citizen as a crime. Sometimes they have little time to do so, sometimes they do not believe the citizen, and sometimes they deliberately fail to record a crime to make it seem that they are doing a good job of preventing crime. If they do not record the report, the FBI does not count it as a crime. If the police start recording every report, the official crime rate will rise, even though the actual number of crimes has not changed. In a third problem, if crime victims become more likely to report their crimes to the police, which might have happened after the 911 emergency number became common, the official crime rate will again change, even if the actual number of crimes has not changed.

The Types and Correlates of Crime and Victimization

Data sources give us a fairly good understanding of the types of crime, of who does them and who is victimized by them, and of why the crimes are committed. We have already looked at the “why” question when we reviewed the many theories of deviance. Let’s look now at the various types of crime and highlight some important things about them.

One type of crime is conventional crime, which are the violent and property offenses that worry average citizens more than any other type of crime. The number of violent and property crimes in the U.S. in 2016 amounted to over 9 million, according to FBI data (or more, given the underreporting discussed above). In addition to the physical toll on victims of such crimes the cost to victims amounts to almost $20 billion each year in property losses, medical expenses, and time lost from work.

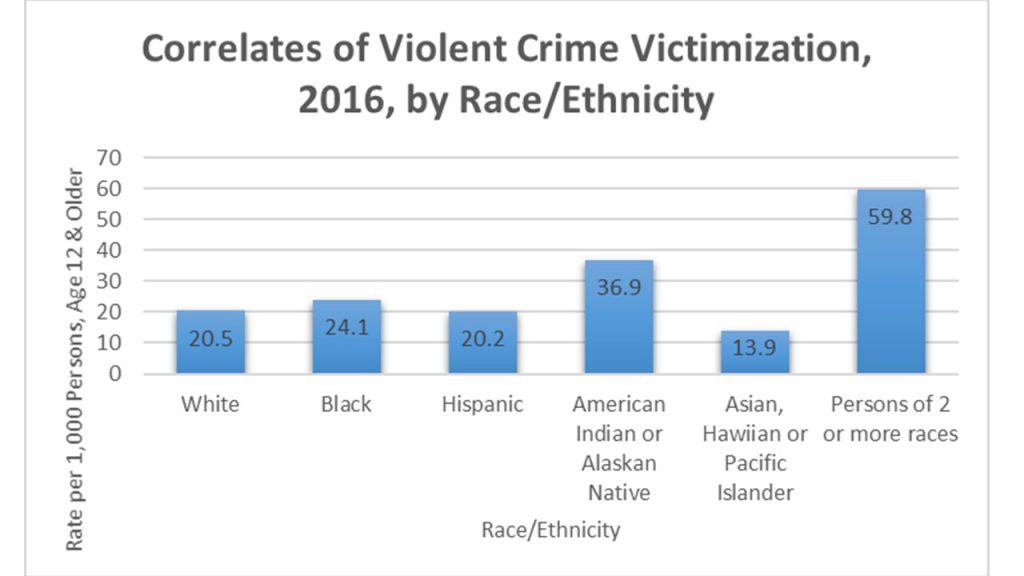

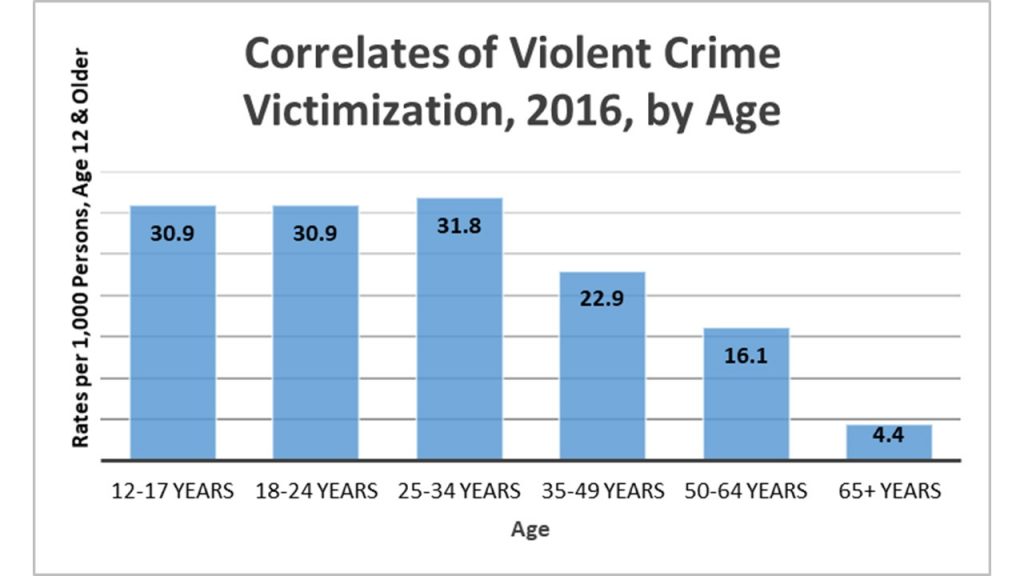

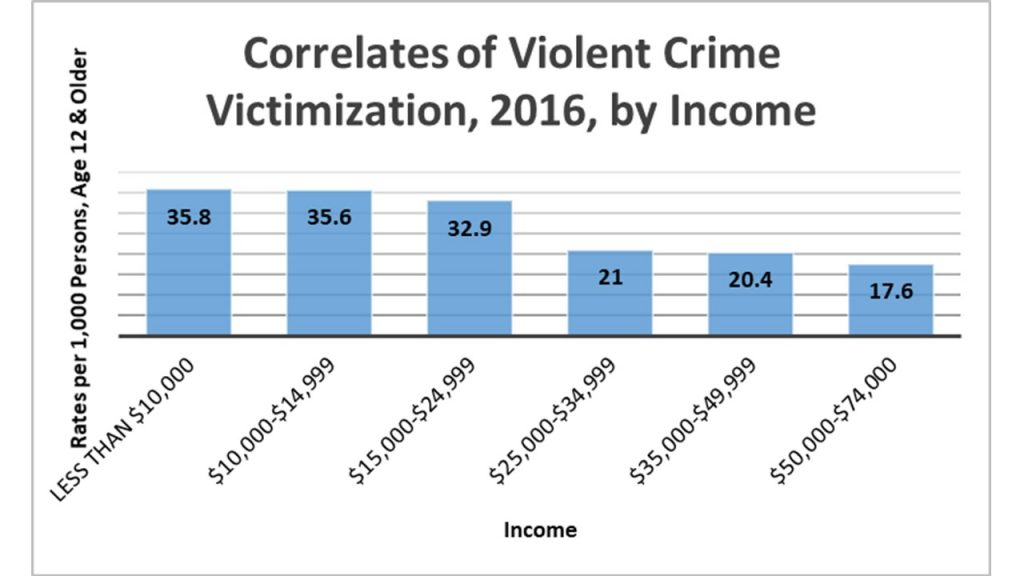

Rates of violent crime victimization in 2016 was fairly close for males and females. For males, the rate of total violence per 1,000 persons age 12 or older was 21.4, while for females the figure was 20.8 (Morgan & Kena, 2017). However, when looking at differences in violent crime victimization by race, age and household income, the differences are stark, as shown below in Figure 7.4: “Correlates of Violent Crime Victimization, 2016.” The tables below demonstrate that the rate of crime victimization varies by race, with Black, American Indians, Alaska Natives and multiracial people disproportionately impacted. Similarly, younger people and lower income individuals are more likely to be victimized.

Figure 7.4 Correlates of Violent Crime Victimization, 2016

Similarly, the rate of violent crime victimization varies by location of residence. Violent crime is more common in urban areas than in rural and suburban communities. The rate of violent crime victimization in urban areas is 29.9 per 1,000 persons age 12 or older, and 15.4 and 21.7 in suburban and rural areas, respectively. It varies geographically in at least one other respect, and that is among the regions of the United States. Rates of violent crime victimization in 2016 were highest in the Midwest and West, and lowest in the Northeast and South (Morgan & Kena, 2017).

When it comes to crime, we fear strangers much more than people we know, but crime data suggests our fear is somewhat misplaced (Truman & Rand, 2010). In cases of assault, rape, or robbery, data shows that strangers commit only about 42% of these offenses, meaning that 58% of the offenses, or well over half, are committed by someone the victim knows. Another important fact about conventional crime is that most of it is intraracial (not to be confused with interracial) , meaning that the offender and victim are usually of the same race. For example, 84% of all single offender–single victim homicides in 2009 involved persons who were either both white or both Black (Federal Bureau of Investigation).

Who is most likely to commit conventional crime? Data collected by the FBI from police departments nationwide show that a disproportionate number of crimes are committed by males, with the exceptions of larceny-theft, embezzlement and prostitution. Of the 8.3 million people arrested in 2015, 6.1 million were male, or 73.1% of all arrests (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2015). Table 7.3: “Arrests by Sex, 2015” shows examples of this difference.

Table 7.3 Arrests by Sex 2015

| Offense Charged | # of Arrests | Percent Male | Percent Female |

| Murder | 8,533 | 88.5 | 11.5 |

| Rape | 17,504 | 97.1 | 2.9 |

| Robbery | 73,230 | 85.6 | 14.4 |

| Aggravated Assault | 288,815 | 76.9 | 23.1 |

| Burglary | 166,609 | 81.1 | 18.9 |

| Larceny-Theft | 900,077 | 56.8 | 43.2 |

| Motor Vehicle Theft | 59,831 | 78.8 | 21.2 |

| Arson | 6,802 | 80.3 | 19.7 |

| Forgery and Counterfeiting | 42,681 | 64.7 | 35.3 |

| Fraud | 102,339 | 61.3 | 38.7 |

| Embezzlement | 12,247 | 49.8 | 50.2 |

| Weapons; carrying, possessing, etc. | 111,316 | 91.1 | 8.9 |

| Prostitution | 31,534 | 36.0 | 64.0 |

| Drug Abuse Violations | 1,144,021 | 77.4 | 22.6 |

| Offenses against family and children | 72,418 | 71.3 | 28.7 |

| D. U. I. | 833,833 | 75.1 | 24.9 |

| Drunkenness | 314,856 | 80.5 | 19.5 |

| Disorderly Conduct | 298,253 | 71.8 | 28.2 |

Source: Data from Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2015). Crime in the United States, 2015. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2015/crime-in-the-u.s.-2015/tables/table-42

Despite much controversy over what racial differences in arrest mean, rates of arrests vary by racial-ethnic group. The rate of arrest for both Non-Hispanic whites and Blacks were disproportionately higher than their overall population size. For instance, the non-Hispanic white population in 2016 was 61.3% of the total U.S. population, yet non-Hispanic whites made up 69.6% of all arrests in the nation. Similarly, the Black population was 12.7% of the overall population in 2016, while 26.9% of arrests were of Black people in that same year. Table 7.4: “Arrests by Race and Ethnicity, 2016” shows rates of arrest for U.S. racial and ethnic groups, along with their portion of the overall population.

Table 7.4: Arrests by Race and Ethnicity, 2016

| Racial-Ethnic Group | % of the U.S. Population | % of Arrests* |

| White | 61.3 | 69.6 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 17.8 | 18.4 |

| Black | 12.7 | 26.9 |

| Asian American | 4.8 | 1.2 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | .9 | 2.0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | .2 | .3 |

*% of arrests are broken down by race and by ethnicity by the FBI. The percentage for the Hispanic/Latino population is compared with other non-Hispanic/Latino ethnic groups. All other groups above are listed as racial groups and are compared to other racial groups. This is why the % of Arrests column does not add up to 100%.

Source: Data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2016). Crime in the United States, 2016. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/resource-pages/tables/table-21

Social class also plays a role in conventional crime rates. Most people arrested for conventional crime have low levels of education and low incomes. Such class differences in arrest can be explained by several of the explanations of deviance already discussed, including strain theory. Note, however, that wealthier people commit most white-collar crimes. If the question is whether social class affects crime rates, the answer depends on what kind of crime we have in mind.

One final factor affecting conventional crime rates is age. The evidence is very clear that conventional crime is disproportionately committed by people age 30 and under. For example, people in the 10–29 age group account for about 49.8% of all arrests (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2017). During adolescence and young adulthood, peer influences are especially strong and “stakes in conventional activities,” to use some sociological jargon, are weak. Once we start working full time and possibly get married, our stakes in society become stronger and our sense of responsibility grows. We soon realize that breaking the law might be much costlier than when we were young.

White-Collar Crime

White-collar crime is crime committed as part of one’s occupation. It ranges from fraudulent repairs by auto repair shops to corruption in the high-finance industry to unsafe products and workplaces in some of our largest corporations. It also includes employee theft of objects and cash. Have you ever taken something without permission from a place where you worked? Whether or not you have, many people steal from their employees, and the National Retail Federation estimates that employee theft involves some $49 billion annually (National Retail Federation, 2017). White-collar crime also includes health-care fraud, which is estimated to cost some $100 billion a year as, for example, physicians and other health-care providers bill Medicaid for exams and tests that were never done or were unnecessary (Rosoff, Pontell, & Tillman, 2010). And it also involves tax evasion: the IRS estimates that tax evasion costs the government some $400 billion annually, a figure many times greater than the cost of all robberies and burglaries (Matthews, 2016).

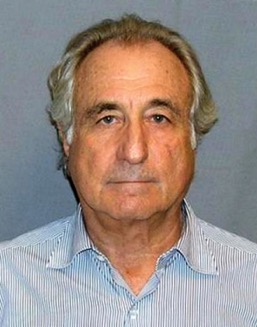

One of the most serious recent examples of white-collar crime came to light in December 2008, when it was discovered that 70-year-old investment expert Bernard Madoff had engaged in a Ponzi scheme (in which new investments are used to provide the income for older investments) since the early 1990s in which he defrauded thousands of investors of an estimated $50 billion, the largest such scandal in U.S. history (Creswell & Thomas, 2009). Madoff pleaded guilty in February 2009 to 11 felonies, including securities fraud and money laundering, and was sentenced to 150 years in prison (Henriques & Healy, 2009).

Some of the worst crime is committed by our major corporations, known as corporate crime. As just one example, price fixing in the corporate world costs the U.S. public about $60 billion a year (Simon, 2006). Even worse, an estimated 50,000 workers die each year from workplace-related illnesses and injuries that could have been prevented if companies had obeyed regulatory laws and followed known practices for safe workplaces (AFL-CIO, 2007). A tragic example of this problem occurred in April 2010, when an explosion in a mining cave in West Virginia killed 29 miners. It was widely thought that a buildup of deadly gases had caused the explosion, and the company that owned the mine had been cited many times during the prior year for safety violations related to proper gas ventilation (Urbina, 2010).

Corporations also make deadly products. In the 1930s the asbestos industry first realized their product was dangerous but hid the evidence of its danger, which was not discovered until 40 years later. In the meantime, thousands of asbestos workers came down with deadly asbestos-related disease, and the public was exposed to asbestos that was routinely put into buildings until its danger came to light.

Asbestos is not the only unsafe product. The Consumer Product Safety Commission and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that about 10,000 Americans die annually from dangerous products, including cars, drugs, and food (U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission, 2003; Petersen & Drew, 2003). In perhaps the most notorious case, Ford Motor Company marketed the Pinto even though company officials knew the gas tank could catch fire and explode when hit from the rear end at low speeds. Ford had determined it could fix each car’s defect for $11 but that doing so would cost it more money than the amount for lawsuits it would eventually pay to the families of dead and burned Pinto victims if it did not fix the defect. Because Ford decided not to fix the defect, many people—estimates range from two dozen up to 500—people died in Pinto accidents (Cullen, Maakestad, & Cavender, 2006). In a more recent example involving a motor vehicle company, Toyota was fined $16.4 million by the federal government in April 2010 for allegedly suppressing evidence that its vehicles were at risk for sudden acceleration. The government’s announcement asserted that Toyota “knowingly hid a dangerous defect for months from U.S. officials and did not take action to protect millions of drivers and their families” (Maynard, 2010, p. A1).

Corporations also damage the environment, as the BP oil spill that began in April 2010 reminds us. Because federal laws are lax or nonexistent, corporations can and do pollute the environment with little fear of serious consequences. According to one report, one-fifth of U.S. landfills and incinerators and one-half of wastewater treatment plants violate health regulations (Armstrong, 1999). It is estimated that between 50,000 and 100,000 Americans and 300,000 Europeans die every year from the side effects (including heart disease, respiratory problems, and cancer) of air pollution (BBC News, 2005); many of these deaths would not occur if corporations followed the law and otherwise did not engage in unnecessary pollution of the air, water, and land. Critics also assert that laws against pollution are relatively weak and that government enforcement of these laws is often lax.

Is white-collar crime worse than conventional crime? The evidence seems to say yes. A recent estimate put the number of deaths from white-collar crime annually at about 110,000, compared to 17,000 to 18,000 from homicide. The financial cost of white-collar crime to the public was also estimated at about $565 billion annually, compared to about $18 billion from conventional crime (Barkan, 2012). Although we worry about conventional crime much more than white-collar crime, the latter harms the public more in terms of death and financial costs.

Scholars attribute the high level of white-collar crime, and especially of corporate crime, to one or more of the following: (a) greed arising from our society’s emphasis on economic success, (b) the absence of strong regulations governing corporate conduct and a severe lack of funding for the federal and state regulatory agencies that police such conduct, and/or (c) weak punishment of corporate criminals when their crimes are detected (Cullen, Maakestad, & Cavender, 2006; Leaf, 2002; Rosoff, Pontell, & Tillman, 2010). Drawing on this understanding, many scholars think that more effective corporate regulation and harsher punishment of corporate criminals (that is, imprisonment in addition to the fines that corporations typically receive when they are punished) may help deter corporate crime.

Victimless Crime

Victimless crime is illegal behavior in which people willingly engage and in which there are no unwilling victims. The most common examples are drug use, prostitution, pornography, and gambling. Many observers say these crimes are not really victimless, even if people do engage in them voluntarily. For example, many drug users hurt themselves and members of their family from their addiction and the physical effects of taking drugs. Prostitutes put themselves at risk for sexually transmitted disease and abuse by pimps and customers. Illegal gamblers can lose huge sums of money. Although none of these crimes is truly victimless, the fact that the people involved in them are not unwilling victims makes victimless crime different from conventional crime.

Victimless crime raises controversial philosophical and sociological questions. The philosophical question is this: should people be allowed to engage in behavior that hurts themselves (Meier & Geis, 2007)? For example, our society lets adults smoke cigarettes, even though tobacco use kills several hundred thousand people every year. We also let adults gamble legally in state lotteries, at casinos and racetracks, and in other ways. We obviously let people of all ages eat “fat food” such as hamburgers, candy bars, and ice cream. Few people would say we should prohibit these potentially harmful behaviors. Why, then, prohibit the behaviors we call victimless crime? Some scholars say that any attempt to decide which behaviors are so unsafe or immoral that they should be banned is bound to be arbitrary, and they call for these bans to be lifted. Others say that the state does indeed have a legitimate duty to ban behavior the public considers unsafe or immoral and that the present laws reflect public opinion on which behaviors should be banned.

The sociological question is just as difficult to resolve: do laws against victimless crimes do more harm than good (Meier & Geis, 2007)? Some scholars say these laws in fact do much more harm than good, and they call for the laws to be abolished or at least reconsidered for several reasons: the laws are ineffective even though they cost billions of dollars to enforce, and they lead to police and political corruption and greater profits for organized crime. Laws against drugs further lead to extra violence, as gangs and other groups fight each other to corner the market for the distribution of drugs in various neighborhoods. The opponents of victimless crime laws commonly cite the example of Prohibition during the 1920s, where the banning of alcohol led to all of these problems, which in turn forced an end to Prohibition by the early 1930s. If victimless crimes were made legal, opponents add, the government could tax the behaviors now banned and collect billions of additional tax dollars.

Those in favor of laws against victimless crimes cite the danger these behaviors pose for the people engaging in them and for the larger society. If we made drugs legal, they say, even more people would use them, and even more death and illness would occur. Removing the bans against behaviors such as drug use and prostitution, these proponents add, would imply that these behaviors are acceptable in a civil society.

The debate over victimless crimes and victimless crime laws will not end soon, as both sides have several good points to make. One thing that is clear is that our current law enforcement approach is not working. More than 1 million people are arrested annually for drug use and trafficking and other victimless crimes, but there is little evidence that using the law in this manner has lowered people’s willingness to take part in victimless crime behavior (Meier & Geis, 2007). Perhaps it is not too rash to say that a serious national debate needs to begin on the propriety of the laws against victimless crimes to determine what course of action makes the most sense for American society.

| Learning from Other Societies

Crime and Punishment in Denmark and the Netherlands Since the 1970s the United States has used a get-tough approach to fight crime; a key dimension of this approach is mandatory sentencing and long prison terms and, as a result, a huge increase in the number of people in prison and jail. Many scholars say this approach has not reduced crime to a great degree and has cost hundreds of billions of dollars. The experience of Denmark and the Netherlands suggests a different way of treating criminals and dealing with crime. Those nations, like most others in Western Europe, think prison makes most offenders worse and should be used only as a last resort for the most violent and most incorrigible offenders. They also recognize that incarceration is very expensive and much more costly than other ways of dealing with offenders. These concerns have led Denmark, the Netherlands, and other Western European nations to favor alternatives to imprisonment for the bulk of their offenders. These alternatives include the widespread use of probation, community service, and other kinds of community-based corrections. Studies indicate that these alternatives may be as effective as incarceration in reducing recidivism (repeat offending) and cost much less than incarceration. If so, an important lesson from Denmark, the Netherlands, and other nations in Western Europe is that it is possible to keep society safe from crime without using the costly get-tough approach that has been the hallmark of the U.S. criminal justice system since the 1970s. (Bijleveld & Smit, 2005; Dammer & Fairchild, 2006) |

7.4 The Get-Tough Approach: Boon or Bust?

It would be presumptuous to claim to know exactly how to reduce crime, but a sociological understanding of its causes and dynamics points to several directions that show strong crime-reduction potential. Before sketching these directions, we first examine the get-tough approach, a strategy the United States has used to control crime since the 1970s.

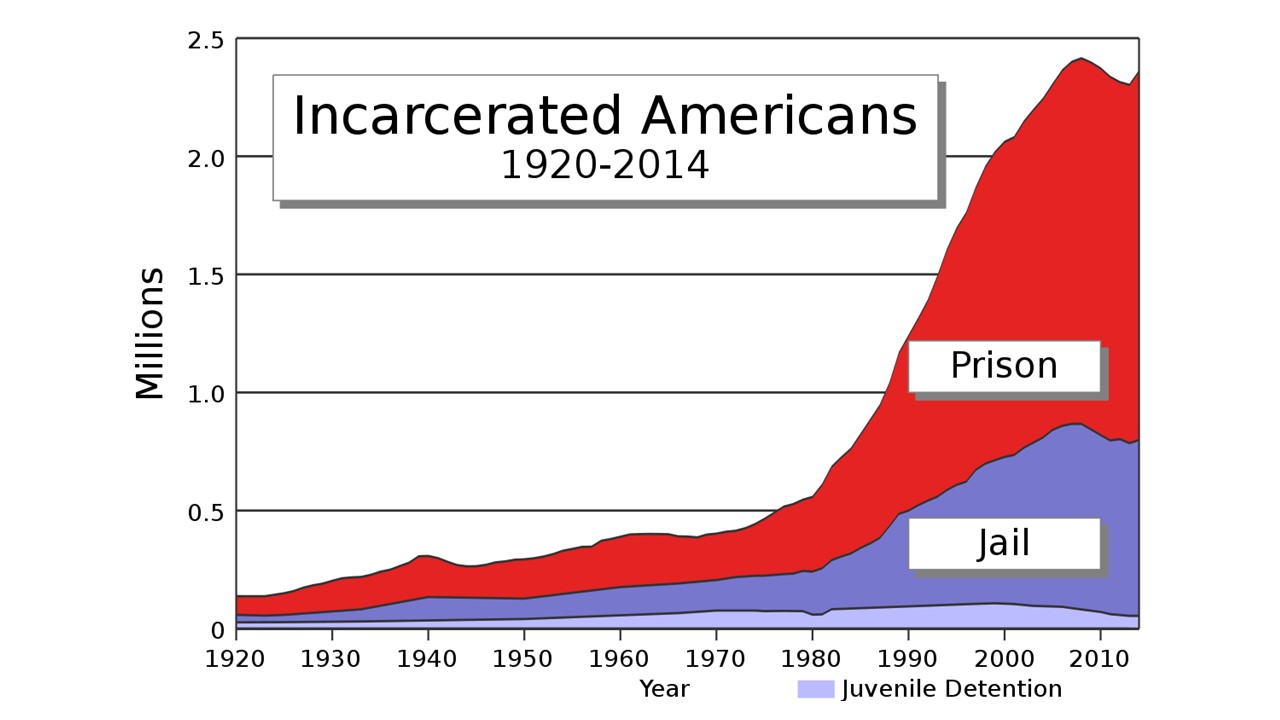

Harsher law enforcement, often called the get-tough approach, has been the guiding strategy for the U.S. criminal justice system since the 1970s. This approach has involved increased numbers of arrests and, especially, a surge in incarceration, which has quintupled since the 1970s. Reflecting this surge, the United States now has the highest incarceration rate by far in the world. Many scholars trace the beginnings of the get-tough approach to efforts by the Republican Party to win the votes of whites by linking crime to Black Americans. These efforts increased public concern about crime and pressured lawmakers of both parties to favor more punitive treatment of criminals to avoid looking soft on crime (Beckett & Sasson, 2004; Pratt, 2008). According to these scholars, the incarceration surge stems much more from political decisions and pronouncements, many of them racially motivated, by lawmakers than from trends in crime rates. As we noted earlier in this chapter, the conventional crime rate has declined significantly. Beckett and Sasson (2004, pp. 104, 128) summarize this argument,

Crime-related issues rise to the top of the popular agenda in response to political and media activity around crime—not the other way around. By focusing on violent crime perpetrated by racial minorities…politicians and the news media have amplified and intensified popular fear and punitiveness.…Americans have become most alarmed about crime and drugs on those occasions when national political leaders and, by extension, the mass media have spotlighted these issues.

Today more than 2.1 million Americans are incarcerated in jail or prison at any one time, compared to only about one-fourth that number 40 years ago (Warren, 2009). This increase in incarceration has cost the nation hundreds of billions of dollars since then. While the size of the correctional population is still extraordinarily high compared to other nations due to changes in policy and practice in the 1970’s and 1980’s, the rate of incarceration did begin to decline slightly in 2008, and has dropped by over 138,000 inmates since that time. Similarly, within this same timeframe, the total correctional population (including prisoners and those on probation or parole) declined from 7,312,600 to 6,613,500 (Kaeble & Cowhig, 2018).

Despite the very large expenditure to maintain such a large prison population, criminologists question whether it has helped lower crime significantly (Piquero & Blumstein, 2007; Raphael & Stoll, 2009). Although crime fell by a large amount during the 1990s as incarceration rose, and continues to decline, scholars estimate that the increased use of incarceration accounted for at most only 10%–25% of the crime drop during this decade. They conclude that this result was not cost effective and that the billions of dollars spent on incarceration would have had a greater crime-reduction effect had they been spent on crime-prevention efforts. They also point to the fact that the heavy use of incarceration today means that some 700,000 prisoners are released back to their communities every year, creating many kinds of problems (Clear, 2007). A wide variety of evidence, then, indicates that the get-tough approach has been more bust than boon.

Recognizing this situation, several citizens’ advocacy groups have formed since the 1980s to call attention to the many costs of the get-tough approach and to urge state and federal legislators to reform harsh sentencing practices and to provide many more resources for former inmates. One of the most well-known and effective such groups is the Sentencing Project, which describes itself as “a national organization working for a fair and effective criminal justice system by promoting reforms in sentencing law and practice, and alternatives to incarceration.” The Sentencing Project was founded in 1986 and has since sought “to bring national attention to disturbing trends and inequities in the criminal justice system with a successful formula that includes the publication of groundbreaking research, aggressive media campaigns and strategic advocacy for policy reform.” The organization’s Web site features a variety of resources on topics such as racial disparities in incarceration, women in the criminal justice system, and drug policy (http://www.sentencingproject.org).

Additionally, many sociologists and other social scientists think it makes more sense to try to prevent crime than to wait until it happens and then punish the people who commit it. That does not mean abandoning law enforcement, of course, but it does mean paying more attention to the sociological causes of crime as outlined earlier in this chapter and to institute programs and other efforts to address these causes. For example, the social ecology approach suggests paying attention to the social and physical characteristics of urban neighborhoods that are thought to generate high rates of crime. These characteristics include, but are not limited to, poverty, joblessness, dilapidation, and overcrowding. Strain theory suggests paying attention to poverty, while the differential association and social control theories remind us of the need to focus on peer influences and family interaction. The labeling theory reminds us of the strong possibility that harsh punishment may do more harm than good, and feminist explanations remind us that much deviance and crime is rooted in the expectations associated with masculinity.

A sociological understanding of deviance suggests the potential of several strategies and policies for reducing conventional crime (Currie, 1998; Greenwood, 2006; Jacobson, 2005; Welsh & Farrington, 2007). Such efforts would include, at a minimum, the following:

- Establish good-paying jobs for the poor in urban areas.

- Establish youth recreation programs and in other ways strengthen social interaction in urban neighborhoods.

- Improve living conditions in urban neighborhoods.

- Change male socialization practices.

- Establish early childhood intervention programs to help high-risk families.

- Improve the nation’s schools.

- Provide alternative corrections for non-dangerous prisoners in order to reduce prison crowding and costs and to lessen the chances of repeat offending.

- Provide better educational and vocational services and better services for treating and preventing drug and alcohol abuse for ex-offenders.

This is not a complete list, but it does point the way to the kinds of strategies that would help get at the roots of conventional crime and, in the long run, help greatly to reduce it. Although the United States has been neglecting this crime-prevention approach, programs and strategies such as those just mentioned would in the long run be more likely than our current get-tough approach to create a safer society. For this reason, sociological knowledge on crime and deviance can indeed help us make a difference in our larger society.

7.5 End-of-Chapter Material

- Deviance is behavior that violates social norms and arouses negative reactions. What is considered deviant depends on the circumstances in which it occurs and varies by location and time period.

- Durkheim said deviance performs several important functions for society. It clarifies social norms, strengthens social bonds, and can lead to beneficial social change.

- Sociological theories related to deviance emphasize different aspects of the social environment as contributors to deviance and crime.

- Crime in the United States remains a serious problem that concerns the public. Public opinion about crime does not always match reality and is related to individuals’ gender and race among other social characteristics. Women and Black people are especially likely to be afraid of crime.

- Crime is difficult to measure, but the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR), National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), and self-report studies give us a fairly accurate picture of the amount of crime and of its correlates.

- Several types of crime exist. Conventional crime includes violent and property offenses and worries Americans more than any other type of crime. Such crime tends to be intraracial, and a surprising amount of violent crime is committed by people known by the victim. White-collar crime is more harmful than conventional crime in terms of personal harm and financial harm. Victimless crime is very controversial, as it involves behavior by consenting adults. Scholars continue to debate whether the nation is better or worse off with laws against victimless crimes.

- To reduce crime, most criminologists say that a law-enforcement approach is not enough and that more efforts aimed at crime prevention are needed. These efforts include attempts to improve schools and living conditions in inner cities and programs aimed at improving nutrition and parenting for the children who are at high risk for impairment to their cognitive and social development.