Chapter 1: Integration & Inclusion

Whether you are a Japanese or a foreign worker, it is a prerequisite for your motivation to feel that your job is integrated into an important strategy of your company. Otherwise, you feel like a slave, just doing what you are told to do without any clear purpose just for salary to survive. You are not dead but not alive either. It is called a feeling of “社畜,”[pron: shachiku] literally meaning “company slave or company farm animal” in Japanese. It is shocking to observe that so many workers in Japan admit that they are corporate slaves and seem to have accepted this situation as an unavoidable way of life.

Integration also has another dimension when we consider the non-Japanese workforce. Are those non-Japanese employees well integrated into the total workforce of a Japanese company? Or are they still treated as nonintegrated resources of the company? Despite all the cultural differences and language barriers, has the company integrated a universal value system that both Japanese and non-Japanese employees can share to function collaboratively in an integrated manner as a global workforce? It is still a widespread feeling among many foreign workers who have worked in Japan for more than two decades not to feel integrated.

Another aspect of integration is work/life integration. The Japanese are notoriously known for long working hours and sacrificing one’s private life for their company. Over the years, their company life becomes the only life they know, and they demand others to accept the same fate. Recently, the remote work/work-from-home due to COVID-19 has forced the Japanese to spend more time at home with their families. Yet, many older Japanese leaders still ignore the worldwide medical advice and continue to commute to work and spend their entire day in the office. Strangely, their view of work/life integration is achieved by not having any private life. For them, their company is their home, and their work is their life. It is not surprising that the younger generations have difficulty understanding such a mentality.

When it comes to inclusion, many Japanese companies have even more serious issues. Over the past several decades, leaders have talked about the need for more diversity. However, most companies are simply increasing the number of female leaders who think and act like middle-aged Japanese men. Also, it seems Japanese companies are simply promoting foreigners who think and act like middle-aged Japanese men when it comes to globalization. This is not real diversity, is it? If everybody still thinks and acts like middle-aged Japanese men regardless of gender and nationality, they are not so different from the stormtroopers we see in Star Wars!

As it is often said, “Inclusion is what makes diversity work!”. If there is no inclusion culture, which is to accept, respect and even celebrate different ways of thinking and doing things, Japanese leaders and companies will never graduate from the cadet academy of stormtroopers and compete in the global community.

In this chapter, we would like to review some essential topics and share insights from our regular Third Way Forum discussions.

Collectivism & Individualism

Traditionally, the Japanese corporate culture is based on the mentality of collectivism. We still often hear “we, the Japanese,” “our company.” Even outside of work, collectivism has a major role in Japan. Families are enforcing children from an early age to be considerate of others and not bother other people. However, the consideration the Japanese were trained to deliver is often limited to those within the same group. When it comes to people outside their own group, people are pretty indifferent.

The Hofstede Cultural Compass shows Japan pointing at 42, Canada 80, Denmark 74, and the United States at 91 in Individualism. The higher values represent the society’s values of individualism, and the lower values show the preference for collectivism.

The fear of being excluded from the group has been a powerful driver to mould Japanese society and behavior. Over the past several decades, if you were not invited to a drinking session after work, you could feel excluded and worried about your status in the company. But these days, young people do not share such an old practice. They often reject such a drinking session with their bosses as it is not a paid working time. Thanks to the increasing remote working time due to COVID-19, the pressure to go drinking has radically decreased as well. However, older corporate leaders still carry over their old mentality, and they miss this drinking culture. Some actively conduct online drinking sessions after work, preferring to be more with colleagues than with friends. It’s important to notice that most Japanese workers have made their colleagues their closest friends after working together for decades in the same company.

Although older Japanese leaders emphasize the importance and strength of creating a hierarchical collective culture, we argue that collectivism’s values may be overrated. Collectivism may have worked as a strength in manpower-heavy manufacturing in the old days but is less required in today’s service and the digital economy.

So what is the benefit of collectivism then? Probably collectivism provides safety and comfort and a sense of belonging. Also, a team can often achieve more than many individuals working on their own. However, people can still feel lonely even if they work together with other people because loneliness is a mental state. As we can see walking the streets in Tokyo, there are many lonely people in a big city like Tokyo.

For developing innovative ideas and new concepts, collectivism could work negatively. When Japanese companies face many challenges like today, just having many obedient employees with a strong collectivist attitude could be suicidal. They are doubtful to make any innovation and transformation happen. Without a much more individualistic approach and a much stronger sense of self-responsibility in every employee, it is very unlikely for any Japanese company to survive in today’s idea-based business competition.

So the question is, why don’t the Japanese people rebel against collectivism?

Most Japanese people are used to doing their work, as a fixed routine, in the same way as they do their daily laundry. That’s why the Japanese people are extremely good at doing the same things from the past, as it requires no thinking of their own and without any emotional involvement. This style of working has completely knocked off their last spirit of rebellion and creativity. They have indeed become 社畜(corporate slaves), as many of them happily admit.

If we are serious about transforming the corporate culture in Japan by defeating the outdated mentality of strong collectivism, we need to start by releasing the Japanese people from their self-imposed slavery. As the first step, let the Japanese people speak up! Companies should make it very clear, not only on their recruitment webpage and in a town-hall speech of executives, that they truly want people to speak up straight from their guts by awarding those who do and punishing those who don’t. Knowing that their ship is sinking, rewarding the obedient sailors who keep steering the ship on a wrecking course is insanity. Start awarding those who rebel and adjust the course to avoid the shipwreck.

Let’s hope that the increased remote working will force Japanese companies to knock out the overrated collectivism and embrace much more individualism in every employee for the sake of long-overdue innovation and transformation they desperately need.

Teamwork

So what about teamwork then? Japanese people are very proud of their teamwork attitude, and Japanese movies and cartoons are full of beautiful stories of strong teamwork. It is often said that Japanese people have a strong work ethic of doing their best for the team rather than becoming the best in the team. Teamwork is surely one of the most vital traits of the Japanese corporate culture.

But here comes a question. If the Japanese companies are so good at teamwork, why aren’t they much more successful in the global business world? In recent years, it is obvious that American, European and Chinese companies are much more successful than most Japanese companies, which are rapidly slipping down the top global company list. So, where is the disconnect?

Here is our analysis based on our observation.

Teamwork could be a double-edged sword. Positive cooperation with collaboration, an open mind and diversity create innovation. But damaging teamwork with narrow-mindedness and protectionist mentality just strengthens bureaucracy.

A collaborative team works together to co-create something new that aligns with a shared vision of all of its members. (How Do We Collaborate, Royal Roads University).

As we talked about the Japanese people’s collective mentality above, the lack of individualism is killing the spirit of innovation, transformation and creativity. A team is a group of individuals, and it can be only as strong as the weakest member. Only healthy individuals, who can offer their respective values and skills, can form a strong team. A strong spirit of teamwork alone without a vital contribution from each member does not make a strong team. Long decades of self-imposed corporate slavery, a.k.a. salarymen culture, made Japanese people very weak in their individual contributions regarding professional skills and added values.

It seems those people who always talk about the importance of teamwork often lack their individual contribution. They cannot survive as individual professionals, so as a result, they want to ensure that everybody sticks together as a team so that they are not expelled from the team despite their lack of talent. Japan’s extended talent management policy of developing company-loyal generalists rather than real business professionals who could work in any company made the hollow shout of teamwork louder and louder with an increasing number of unprofessional generalists who cannot survive as individual professionals.

Japanese leaders should apply critical thinking when they think about the teamwork spirit at their companies. Are they talking about real teamwork of real professionals adding value or fake teamwork of insecure generalists who just want to stick together to maintain their non-value-adding existence?

Although many Japanese leaders boast about the power of teamwork of their company employees, quite often, great teamwork is demonstrated only when they organize parties, events and logistical matters and not demonstrated enough in other aspects of the company management such as transforming the company, re-aligning their business strategy and quickly putting innovative products in the market, etc. As long as their proud teamwork spirit is not demonstrated in the critical business matters at all but only in their logistical admin matters, it is not surprising that foreigners think that Japanese teamwork is totally overrated. Teamwork has to be demonstrated in victory. Not just as a battle cry in a tiny logistical skirmish.

At this moment, it seems the teamwork at many Japanese companies is just an old tool to strengthen their existing bureaucracy. Successful companies have a passion for their mission, and their passion is much stronger than bureaucracy. That’s why they prevail. Every Japanese leader should now ask themselves. Is the teamwork at our company a real one driven by your mission and passion and delivered by each professional’s contribution? Or is it just a fake one only prolonging self-preserving bureaucracy?

Senpai – Kohai Hierarchy

The terms senpai (先輩, “senior”) and kohai (後輩, “junior”) are used in Japan for an informal but still strong hierarchical interpersonal relationship between seniors (those with more experience) and juniors (those with less experience). The terms are used not only in business organizations but also used from elementary school through to university. The concept has its roots in Confucianism, which was also widely taught in Japan for centuries. Today’s senpai-kohai notion emerged in the Meiji era in the development of Japan’s bureaucratic control in the military and school system (Sakaiya, 2003)

After the Edo-period class systems (1st class: Samurai, 2nd class: Farmers, 3rd class: Craftsman, 4th class: Merchants) were abolished, the ranks and age differences became the major drivers of hierarchy. Today’s senpai-kohai relationship is probably not as strong as a few decades ago, but it still exists in today’s Japanese corporate world. Initially, the concept was healthy: older/senior people shall take care of younger/junior people. However, it became unhealthy when this relationship was deemed obligatory, and junior people felt forced to obey senior people regardless of their respectability.

In Japanese companies, if you have just discovered that someone happens to have graduated from the same university and that person happens to be older than you, that person is automatically your senpai. Even if you did not know that person until now, you feel obligated to call him senpai from now on. And that older person may try to use you or abuse you more often from now on as he or she now knows that you are a Kohai. This kind of unreasonable obligatory feeling is absolutely unhealthy since it facilitates abuse (Zain, 2018)

In the old days, age and experience brought more knowledge and wisdom. So it was natural that older people could help younger people as seniors. However, in today’s digital age, power is more to do with ideas for innovation, creation and transformation. So being an older person does not necessarily mean that he or she has more knowledge, experience and power to help a younger person.

Therefore, reverse mentoring is getting more common in big global companies in the West, where older corporate executives get mentors in their 20’s to learn about how today’s young people communicate with each other and their future needs. Japanese companies should adopt this kind of practice more often.

At Japanese schools, if you join a school sports club, it is expected that first-year students are taken care of by sophomores. Juniors actually do the club’s real jobs, and seniors just hang around to do whatever they want. This school practice continues beyond schools, and many Japanese companies are running in the same way. Young leaders take care of first-year students, middle managers do the company’s real jobs, and seniors just hang around until their retirement.

Seniority mentality is also deeply embedded in the Japanese language. It is difficult to speak up to senior people in Japanese simply because the Japanese language is structured to force people to apply a respectful usage of the language (Keigo) to seniors clearly. As long as people speak the Japanese language only, it is impossible to speak up directly to seniors without being regarded as rude and inappropriate.

Therefore, it may be useful to switch to English in the business environment when you want to make an important point clearly to senior Japanese corporate leaders. At least most Japanese leaders can read English. So on your presentation slide, write in big English letters what you have to say. Then it does not sound rude because English is a direct language.

A mentor-student relationship exists everywhere globally, and it could be compelling if it is spontaneously formed by free will and conducted out of mutual respect and for personal growth. But in Japan, the senpai-kohai relationship often seems to be over-engineered, abused and rather hindering people from their personal growth and innovative ideas.

Maybe it is better to stop using the words senpai-kohai altogether as it carries unhealthy notions and practices from the past.

Just call them “master” & “apprentice” only if such a relationship naturally evolves between the two people out of their free will.

Gender Equality

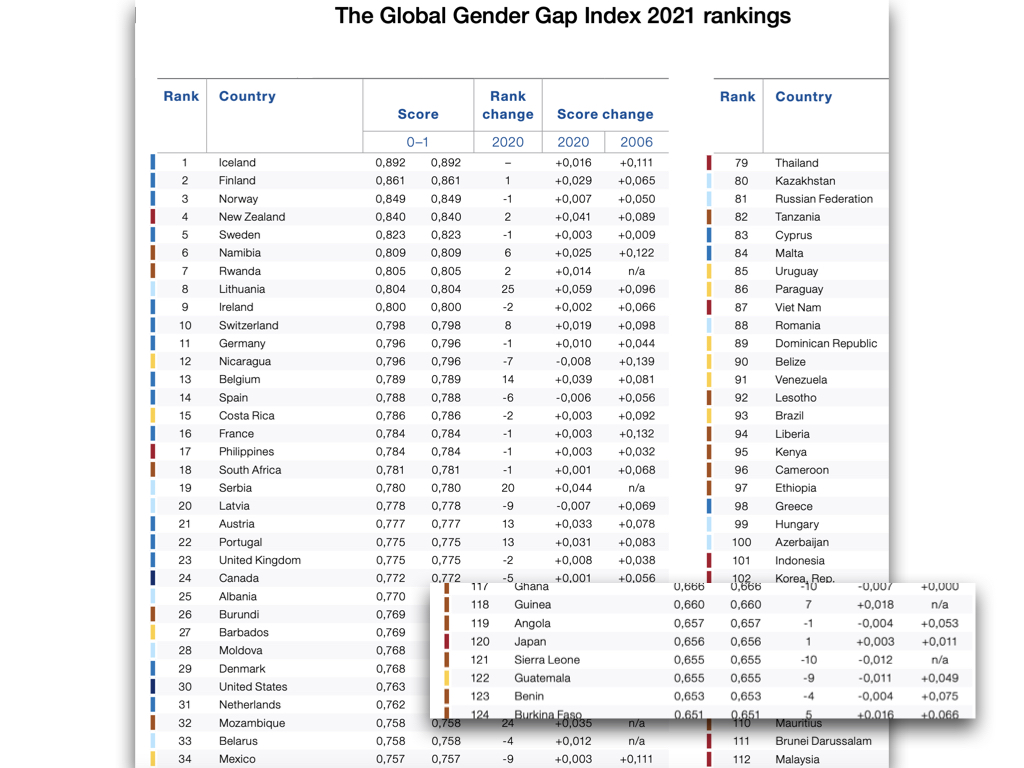

Japan placed 120th out of 156 countries in the World Economic Forum’s gender equality rankings in 2021 (The Global Gender Gap Report, 2021). Despite years of Womenomics promoted by the previous Abe administration, it is clear that the gender equality situation is not improved in Japan. It seems to be getting even worse with recent discriminatory comments in the media about women.

It is fresh in our memory that Mr.Mori, the chairman of Japan’s IOC, had to resign after making discriminatory remarks about women, saying when women attend the meetings, they last long as women talk too much. (Such a comment that lacks respect and generalizing women with bias is unacceptable; however, there are probably still many old Japanese male leaders who think like Mr. Mori.)

Indeed, gender equality is a continuous challenge globally but appears to be gender discrimination in Japan. Even today, media, ads, and TV shows always show women in subservient roles. In the West, the last Jedi in Star-Wars is female, and the new 007 is a black female. Japan is way behind. In Finland, the prime minister is female in her mid 30’s, and her entire coalition party leaders are all female!

Even in international forums/key company meetings, it is common to have Japanese males making all the keynote presentations. The overwhelming number of participants is male and women running around as support staff or stationed at the reception desk. From a global perspective, it is very odd. A female member of the Forum stated, “It wasn’t only once that I was asked by a female presenter from overseas why there are no women presenters and why I was not assigned. The situation was something familiar for me, but her comment made me realize how odd it looks from a global perspective.” If this situation does not change, Japan will be regarded as an odd country, where people would hesitate to work together on a global project.

Many Japanese companies seem to see specific admin jobs as better suited for women as they think women have more meticulous attention. Such a concept is already a significant bias.

Fifty percent (50%) of Japanese people and consumers are women, yet many companies producing and designing products have totally male-dominant management teams. Women’s purchasing power is undeniably a business reality, yet many Japanese companies still don’t have enough female leaders or feel the need to obtain input from the female viewpoint. In such corporations and meetings, it means 50% of the information is missing. Can it be said that the decisions made in such arrangements are reliable?

Japanese women still seem to be under a lot of social-mental pressure to be cute and supportive of men. These historical, societal expectations for women were based on many years of tradition when a single-family income could support a single family, but this has not been the case since the 1990s.

In addition, women tend to suffer more from “imposter syndrome,” a collection of inadequacy feelings that persist despite evident success compared to men. Especially in Japan, where giving recognition is not common. Even if they were promoted as a manager, women still fear that they were promoted to raise the percentage of female managers (and not because they were good enough). Japanese generally have low self-esteem compared to other countries, and Japanese women especially have low self-esteem issues. Many are brought up without developing enough self-esteem and self-confidence. Even if they are chosen for something, they wonder, “Why me?” because they think they are not good enough. Since many Japanese women still express similar feelings, their overall upbringing should be re-examined and drastically changed in early education.

Also, a lack of female role models, female sponsors, and a lack of recognition of women in the Japanese corporate world discourages Japanese women tremendously. It has been said that women give up becoming managers in the 2nd year after entering the company (after being discouraged by male-dominant society). Many Japanese women still fear becoming managers because their image of a manager is mostly male or male-like females who have given up their private lives for their jobs. And they don’t want to be like them. Maybe Japanese women fear even living their own life. Due to their upbringing, it seems many Japanese women are still self-sabotaged. That’s why many Japanese women haveしょうがない (Shoga-nai) mentality and get used to putting up with what they have got instead of striving to have what they want.

Women in Japan and their partners need to step up more themselves. In human history, the oppressed minorities can never win what they want from the privileged majority unless they stand up and fight for their rights. If the only thing Japanese women can count on for their success is to have their totally male-dominant top management do something drastic to promote women soon, the possibility of their success is quite slim.

Younger Japanese men and women think these days differently, and both gender groups seem to be more aware of the importance of gender equality. However, their seniors, parents and the Japanese media have a strong influence on their perceptions, and they could still end up with the same gender equality gap. We must avoid such a tragedy.

Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/68606

So what can Japanese corporate leaders do to make women (and others) feel their voices are valued?

First of all, the executive management has to clearly communicate how serious they are about fixing the gender equality/discrimination issues in their company. Unclarity from the top management is one of the major causes of no progress in gender equality. What are they trying to achieve? By when and how? The executive management has to communicate it and also mean it by demonstrating it visibly.

Also, to significantly increase female leaders in Japan, male leadership needs (1) to learn and recognize that diverse and inclusive viewpoints help create a better solution to a problem, and (2) to create an environment where women feel safe to speak up, and their opinions are respected.

There are several tangible approaches:

(1) Have an outside speaker talk to the top management within the organization to learn the value of having diversified management from a business perspective. Also, provide examples of a company with diversified management and let them explain the benefits. Japanese leaders need to see real examples and real business benefits as evidence to take action.

(2) To clarify the criteria for promotion to managers and explicitly explain reasons for promotion based on facts to answer “Why me?”

(3) Establish a support system, such as having a mentor whenever a female employee is promoted, to cope with the imposter syndrome (a psychological pattern in which an individual doubts their skills, talents or accomplishments) and overcome the lack of self-confidence. Especially during the first 6 months of promotion, a mentor will be helpful for female managers. In this case, it is recommended to have an outside professional female mentor (i) to keep a safe place where they can really speak out their feelings, (ii) to prevent it from relating to evaluation, and (iii) to learn from the mentor’s experience.

(4) Secure time for 1:1 meeting to provide feedback on what they have done (recognition). At the same time, take time to hear their voice, learn their perspective, and ask what support is needed.

As the last point, we would like to point out that even if company leaders are trying to promote women, we should not forget that our female colleagues are always under the pressure of the gender discriminatory Japanese society. Therefore, the encouraging voice of support for women from the office should be louder than the discouraging voice from their own mothers, mothers-in-law and partners. It means the company leaders’ voice of support for gender equality has to be much louder and clearer to silence those unhealthy noises. And the best way to send such an audible message is to show in action by letting many more women lead and drive business and teams in the company.

Trust Building in the Remote Working Era

Trust building online is a challenge not only in Japan but globally. However, as face-to-face trust-building was a traditional foundation of Japanese business practice, online remote working poses a more significant challenge for Japanese companies.

Japanese business relationships are not as clear-cut as Western business relationships, which are more strictly contract-based. Japanese relationships always have grey areas that are not specified in the contract but are mutually understood or expected for execution. For that grey area to be handled properly, you probably need more trust in the person you are dealing with.

In Japan, trust often comes with the person. If the person is regarded as trustworthy, his/her word or deed is also judged as reliable. If a high-ranked person says something, it tends to be trusted, sometimes even unchecked for its accuracy. On the other hand, if an unknown low-ranked person says something great and really valuable, it may not be taken seriously because the person does not have trustworthy status. We need to consider “trustworthiness vs accuracy.” There is a significant danger or bias in a hierarchical society where the words from the top could be executed without any question or critical thinking.

Consistency in walking the talk is necessary to build trust. But in Japan, many corporate people first look at the title of the person to decide whether or not the person is trustworthy, then his/her appearance, then listens to his/her word and finally sees the actions of the person. We should reverse the process and start by catching the person’s efforts to judge its trustworthiness. If the Japanese people also do that, then trust-building should take much less time.

Quite often, global companies in Japan and ex-pat leaders trust good-English-speaking Japanese simply because they can communicate better in English. But we must separate one’s language ability from trustworthiness. Sometimes you can rely on your intuition or “gut feeling” to judge whether or not to trust a specific person. If your “gut feeling” gives you an uneasy feeling about someone, there is a possibility you should not trust the person. However, “gut feeling” is not based on science, so we must also look at more quantitative analysis to not confuse unconscious bias and discrimination.

Old trust-building tools in Japan, such as playing golf, drinking parties, and going to karaoke/hostess clubs, quickly become irrelevant and unprofessional in the after-COVID-19 remote working era. Mixing personal relationships and professional relationships are creating more problems nowadays as awareness of bias grows. Companies need to provide clear job descriptions and expectations and provide a proper probation period and onboarding support to perform professionally even if they work remotely.

What can we do to build trust online then?

For instance, we could start with a small online meeting with a limited number of people and have a good meeting facilitator to develop a sense of inclusiveness and comfort for all the participants. We could also have more 1:1 meetings online. Especially with those you don’t know yet. Let them talk about themselves, and leaders must listen and speak little.

The word “meeting” could probably make people feel formal and reluctant to open up themselves to those they meet for the first time online. We should replace the word “meeting” with “dialogue,” “conversation,” “talk,”, etc.

To help the audience feel comfortable with you, you can share your LinkedIn information with the participants before the meeting to get the necessary information about you. Younger people are much more tech-savvy, and they have no issue conducting their activities online and build trust fairly quickly among themselves. Older ones are expected to struggle. So they should learn from the younger ones and catch up, or if they don’t want to do that, they must step aside and let the younger leaders take over. The handover from the older leaders to the younger leaders should be happening right now in Japan. But the older ones are the majority of the Japanese. That is the biggest problem. Let’s hope this social shift to remote working and the more tech-savviness requirement will accelerate the required transition of power from the old to the young in many Japanese companies.

Vacation & Work-Life Balance

Vacation is important not only to take a rest but also to learn something new and get inspiration. For most foreigners, a vacation means 2 weeks or 3 weeks off from duty, while many Japanese barely take 2 or 3 days off. There is a historical reason why most Japanese people still hesitate to take a definite number of days off.

Many Japanese people don’t take days off unless there is a specific reason, such as going to a hospital. It is as if they were soldiers on the frontline, and they think they have to keep fighting without rest. Only when they get injured can they retreat to a field hospital for treatment. They feel guilty if they withdraw from the frontline when all other soldiers are still fighting. They don’t want to burden others with work by taking a vacation. Many Japanese buy omiyage (gift) for colleagues even when they take just a few days off. Almost as compensation and apology for the burden his/her absence caused on the colleagues. Though many Japanese are unconscious about it, such a soldier mentality is still firm among Japanese employees. As long as Japanese companies are still run like an army with a strict hierarchy, this unconscious soldier mentality will not go away. Japanese leaders need to adapt much more modern corporate culture if they truly care about their employees’ wellbeing.

Another reason why many Japanese don’t take any long vacation is simply that they don’t feel the need for a break! If they go somewhere, it is usually costly and crowded. Even if they just stay at home, houses in Japan are usually small, so it is better not to stay home too long. They don’t know what to do when they take vacations. Also, imagining a workload piling up when they return to work is another discouraging factor.

Maybe many Japanese don’t know how to enjoy themselves outside their company versus working in the office. Long hours commuting and long working hours did not help them develop much of a life outside their company. Problems are not only with the Japanese workers but the Japanese institutions. Still, in many institutions, the Showa-era’s obsolete practice and culture prevail because Japanese leaders do not set the right tone and not role-model modern behaviors. They still set the tone of working long hours with total commitment, and self-sacrifice is the most glorified virtue. As they demonstrate such examples, their subordinates automatically feel pressured to follow the same behaviors.

If you pay attention to successful Japanese leaders, they are actually very active outside their work. They take regular long vacations and constantly expand their knowledge and experience for their self-development. This is the type of Japanese leaders from whom employees should learn from.

Of course, we should not regard work as bad and vacation as good. Some people genuinely enjoy work or some people don’t enjoy holidays or staying at home. We should not just impose vacations on people. But at the same time, we should allow flexibility in one’s work life and support people to take breaks when they want to take them.

Young Japanese people’s mentality is changing, and they are more willing to handle work-life integration much better and take more extended vacations. However, due to the declining economy, COVID-19 travel restriction, and people shortage at work, people may hesitate to take breaks these days even if they really want to. Japanese company leaders need to decide what kind of message to send and what kind of examples to show to their employees.

Because the situation is challenging, you need every employee to serve to the best of his/her ability. It is critically important that you have a proper mechanism for your employees to recharge and recover regularly without feeling guilty.

Your employees are not soldiers. They are working for the company with their free will. The Japanese may not complain so much, but they normally do so by quietly submitting a sudden resignation letter. Before they are overheated, let them take proper vacations! But first, start by taking your own extended vacations!

Additional Resources

Why all employees should use their vacation days (Ranstad, 2019)