1

1.1 The Rhetorical Situation

The next three chapters concern the rhetorical situation and discuss three critical elements you should have pinned down before you put the pen to paper…errr…before you put the first word on the page. The three critical questions you should ask yourself are:

- Who am I?

- What is my purpose?

- Who is my audience?

It is quite likely you have a purpose, otherwise, you wouldn’t be here. For some of you it might be to get a letter on your college transcript. For others, it might be to become a better writer. Since this handbook focuses on a very specific genre, the argumentative research essay, your overarching purpose is probably both, and probably one more than the other, depending on your mindset. Let’s stop right there. It isn’t that neither of those goals is worthwhile, it is just that 1) you need to be aware of what their relative value is to you, and 2) be ready to set them aside for for the more specific academic purpose you will be asked to accomplish in an advanced composition class, much like you set aside your capacity for disbelief when you walk into a movie theater or a play.

1.1.2 What is an Academic Purpose?

Academic is being used here in a very particular sense. By academic, I mean artificial. I mean it in the same sense a football announcer does when in the last minute of of a 42-17 game he says, “It’s all academic now.” He means there is nothing either team can do to change the score. All efforts are futile, and yet both teams continue to go through the motions either as a formality, because they want to practice, or because they love the game. In that sense, the academic purpose is an artificial construct that has you identifying an imaginary purpose and writing to an imaginary audience. Sometimes you are given some latitude in determining the purpose, while other times you may be assigned a purpose. Then, after you have determined the audience and write your best argument, that audience may never actually read it. This is the game we usually play in English composition class, and although it seems futile, signing on to that purpose will ultimately make the class less like a chore and more like a good movie or an engaging game.

1.2 The Writing Table

To begin, imagine a table. A writing table. There is nothing on this table before you arrive except for, perhaps, a blank sheet of paper. What do you bring to the table? May I suggest, you bring your ME to the table, where ME is an acronym for Mindset and Ethos. You have ideas and experiences, to be sure, but these two items are the first and most important.

1.2.1 Mindset

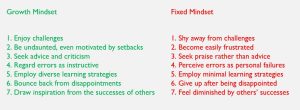

If, after weighing the importance of a letter on your college transcript against becoming a better writer, you decide that the letter on the transcript is the most important thing, odds are that you bring a fixed mindset to the table, whereas if you decide the most important thing is to grow as a writer, then odds are that you bring a growth mindset to the table.

1.2.1.1 Fixed Mindset

In terms of writing, a fixed mindset is based on the fundamental belief that writing ability is innate: either a person is born with it, or they are not. Whether you think you are a good writer or a bad writer, if you have a fixed mindset, you don’t believe you can change that much. If you are already a good writer with a fixed mindset, you might be able to get an A in a composition class without becoming better at all. If you are a bad writer with a fixed mindset, you just have to play it as conservatively as possible and try to jump through all the hoops as best you can to get the highest grade you can, given your innate lack of talent.

1.2.1.2 Growth Mindset

Writers with growth mindsets understand that learning to write is a lifelong process. They are always engaged in the process of becoming. Do not fear mistakes. There are none. -Miles Davis Like other artists, writers never really arrive. There is always room to get better, and an advanced composition class is just another opportunity to practice. The writer with the growth mindset, whether they consider themself a good writer or a bad writer, knows that wherever they are in the process of becoming, they got there through practice. Few people ever become worse at something through practice. They make mistakes, of course, but the growth mindset sees every mistake as an opportunity for growth.

To get anything out of this handbook, you’ll need to take the fixed mindset off the table, and replace it with a growth mindset by embracing challenges, inviting honest feedback rather than seeking praise, taking risks, cultivating curiosity, and practicing persistence. If you agree with the following statement, just add the word “yet” to it, and you are ready to go:

Without yet: I am not the most effective writer.

With yet: I am not the most effective writer yet.

1.2.2 Ethos

Another thing you bring to the table is ethos. Invented ethos is something you will add, but at the beginning it is only situated ethos that you bring to the table. If you aren’t sure what situated ethos is, jump to the ethos chapter and read up on it real quickly. Rhetoric is not just the reputation you have in the community, but the actual quality of your character. While quality of character might mean different things to each of you, in each case it is the backbone of situated ethos. Below is a chart that details what quality of character, or virtue, meant to Aristotle. He offers that certain “fields of feeling” might have good and bad aspects, but that the fundamental spirit of character is capturing the best essence of the virtue, which he shows in the middle column of the chart. Because a virtuous character is so central to classical rhetoric, any aspiring writer, which we all are now that a fixed mindset is off the table, should think about constructing their own chart, and to aspire to the highest virtues they can imagine for themself.

1.3 I

Now that you have your ME at the table, there is one more thing to remember, and that is your I. Previous experience in English composition classes might have taught you that your I should be left out of academic writing, and while that is true to some extent, it is less true than ever in college writing. Since rhetoric is more about choices and their consequent effects, I encourage you to always keep your I on the table. Remember that leaving I out usually has the effect of making the writer seem more objective, but at the same time, it has the effect of distancing you from your reader. You will notice in this chapter I use the I voice, and that is because I think it is more appropriate to use while talking about you, the writer. If you want to explore the benefits of keeping I on the table, check out the essay “I Need you to say I: Why First Person is Important in College Writing” by Kate Mckinney Maddalena.

1.3.1 Who am I?

Once you have taken a fixed mindset off the table, the rhetorical situation is changed. If you have decided that your overall purpose is to grow as a writer, that is still on the table, but that is no longer part of the academic rhetorical situation you will pursue as you compose an argumentative research essay. The old model of the rhetorical situation is off the table:

Old Rhetorical Situation

- Writer: You

- Purpose: To get a grade.

- Audience: The Instructor.

New Rhetorical Situation

- Writer: You

- Purpose: To be determined by you through the process of invention.

- Audience: To be determined by the purpose.

Later you will find it useful to ask questions about authors that may be writing in other rhetorical situations, but as you prepare to write, the focus is on you. This should be a time of introspection, where you analyze yourself in exactly the same way you analyze your audience. It is a good idea to complete the audience worksheet for both you and your audience, since your values, opinions, attitudes, beliefs, and biases are just as important as those of your audience. Make sure to ask yourself these questions both before beginning to write:

- Why am I writing?

- What are my beliefs regarding this topic?

- What are my opinions on this topic?

- What are my attitudes toward this topic?

- What are my attitudes toward my potential audience?

- How am I similar to/different from my potential audience?

- What am I curious about in regard to this topic?

- What personal experiences do I have that inform this topic?

- In what ways am I an authority on this topic?

- What are my biases regarding this topic?

1.4 Awareness

1.4.1 Rhetorical Awareness

Rhetorical awareness is a term that refers to the ability to identify and parse rhetorical situations, which consist of writers, purposes, and context. The context can include historical, cultural, geographical, or other contextual frames. All of these factors taken together then determine the genre. A writer who has a high rhetorical awareness can see these elements in all sorts of diverse situations, from the television news, to print advertisements, to ordering a drink at McDonald’s. But there is an even higher level of awareness that is important to writers as well, and that kind of awareness can only come in a sustainable way from contemplative practices.

1.4.2 Contemplative Practices

Meditation is only one among many types of contemplative practices, but what they all have in common is the intention to escape from words and experience the world directly in the moment: mindfulness. Ironically, some people use writing itself, which necessarily involves words, as a contemplative practice. Below are a few contemplative practices.

1.4.2.1 Meditation

Find a quiet spot to sit.

- Set a 20-minute timer with a gentle sound that will alert you when the time is up.

- Close your eyes and pay attention to the sound and feel of your breath. Don’t breathe differently, just focus your attention on the breath.

- If a thought occurs to you let it float gently past like a cloud or visualize yourself writing it on a sheet of paper. In a variation of this for writers, try writing the thought down in one word on a sticky note and throwing it into an empty trash can. Later you can go through the sticky notes and see what is really cluttering up your brain!

1.4.1.2 5 Senses Centering Activity

Find an interesting place where you can sit without being disturbed.

- Write down five things you can see.

- Close your eyes. Note 4 things you can hear.

- Note 3 things you can feel.

- Note 2 things you can smell.

- Note one thing you can taste.

1.4.1.3 Breathe

- Install the Breathe app on your i-phone and use it or count the following breathing intervals manually for at least 5 cycles.

- Inhale for 4 seconds

- Hold for 7 seconds.

- Exhale for 8 seconds.

- End hold.

- Repeat.

1.5 Cognitive Biases

A cognitive bias is a state of mind or a way of thinking that closes your thinking to certain possibilities, or distorts your thinking in a way that is undesirable. Wikipedia has compiled a huge list of them, but here are just a few that writers are particularly susceptible to. These biases apply to both the writer and the audience, but in order to be clear minded and aware, the writer should be aware of her own biases before making a claim and conducting research.

1.5.1 Anchoring

The tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor”, on one trait or piece of information when making decisions or seeking new information (usually the first piece of information acquired on that subject).

1.5.2 Attentional Bias

The tendency of perception to be affected by recurring or persistent thoughts. Note that the contemplative practices above can help with this.

1.5.3 Availability Heuristic

The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events with greater “availability” in memory, which can be influenced by how recent the memories are or how unusual or emotionally charged they may be.

1.5.4 Backfire Effect

The reaction to disconfirming evidence by strengthening one’s previous beliefs.

1.5.5 Belief Bias

An effect where someone’s evaluation of the logical strength of an argument is biased by the believability of the conclusion.

1.5.6 Compassion Fade

The predisposition to behave more compassionately towards a small number of identifiable victims than to a large number of anonymous ones.

1.5.7 Clustering Illusion

The tendency to overestimate the importance of small runs, streaks, or clusters in large samples of random data (that is, seeing phantom patterns)

1.5.8 Confirmation Bias

The tendency to search for, interpret, focus on and remember information in a way that confirms one’s preconceptions

1.5.9 Decoy Effect

Preferences for either option A or B change in favor of option B when option C is presented, which is completely dominated by option B (inferior in all respects) and partially dominated by option A

1.5.10 Distinction Bias

The tendency to view two options as more dissimilar when evaluating them simultaneously than when evaluating them separately.

1.5.11 Expectation Bias

The tendency for experimenters to believe, certify, and publish data that agree with their expectations for the outcome of an experiment, and to disbelieve, discard, or downgrade the corresponding weightings for data that appear to conflict with those expectations.

1.5.12 Groupthink

The psychological phenomenon that occurs within a group of people in which the desire for harmony or conformity in the group results in an irrational or dysfunctional decision-making outcome. Group members try to minimize conflict and reach a consensus decision without critical evaluation of alternative viewpoints by actively suppressing dissenting viewpoints and by isolating themselves from outside influences.

1.5.13 Irrational Escalation

The phenomenon where people justify increased investment in a decision, based on the cumulative prior investment, despite new evidence suggesting that the decision was probably wrong. Also known as the sunk cost fallacy.

1.5.14 Leveling and Sharpening

Memory distortions introduced by the loss of details in a recollection over time, often concurrent with sharpening or selective recollection of certain details that take on exaggerated significance in relation to the details or aspects of the experience lost through leveling. Both biases may be reinforced over time, and by repeated recollection or re-telling of a memory.

1.5.15 Misinformation Effect

Memory becoming less accurate because of interference from post-event information

1.5.16 Mood Congruent Memory Bias

The improved recall of information congruent with one’s current mood.

1.5.17 Overconfidence Effect

Excessive confidence in one’s own answers to questions. For example, for certain types of questions, answers that people rate as “99% certain” turn out to be wrong 40% of the time.

1.5.18 Proportionality Bias

Our innate tendency to assume that big events have big causes, may also explain our tendency to accept conspiracy theories

1.5.19 Salience Bias

The tendency to focus on items that are more prominent or emotionally striking and ignore those that are unremarkable, even though this difference is often irrelevant by objective standards.

1.5.20 Selective Perception

The tendency for expectations to affect perception.

1.5.21 Semmelweis Reflex

The tendency to reject new evidence that contradicts a paradigm.

1.5.22 Suggestability

A form of misattribution where ideas suggested by a questioner are mistaken for memory.

1.5.23 Testing Effect

The fact that you more easily remember information you have read by rewriting it instead of rereading it.

1.5.24 von Restorff Effect

That an item that sticks out is more likely to be remembered than other items

These are just a few of the many biases that affect our thinking. There are hundreds more, so any time you start to think you don’t have bias, check those that are listed here, and then check the “List of Cognitive Biases” at www.Wikipedia.org for more. These are not only biases that you might have, but audiences your sources might have as well. Anytime you are looking for bias, check this list. Humans are notorious for harboring complex networks of irrational biases.

1.6 Kairos and the Writer

1.6.1 Currency

It isn’t hard for writers of any age to lapse into irrelevancy. As writers move from one age group to the next, they are likely to lose touch with the discourse communities they might have just left behind. Of course, as a writer, it is important to be “in tune” with the audience or discourse community you are addressing, but it is just as important to at least remain aware of current trends. Aside from cultivating and satisfying a sense of curiosity and a growth mindset, here are some specific ways to stay in touch with both the old and the new. All of them are ways of listening, just in more general ways than those described in the Memory: Intertextuality I chapter. Also, while some might suggest that you focus your listening on more academic or informational sources, it is important to pay attention to popular sources as well, since that is where popular culture gets recorded.

1.6.1.1 Reading

Both reading print and online texts helps keep your vocabulary current as well, since you learn both new words, new usages of old words, and new contexts for words.

1.6.1.1.1 General Reading

It is a good idea for a writer to keep a reading schedule that includes general reading, even if they are working on a project that requires them to focus their attention on a specific topic. This reading should be diverse, including works of different genres and time periods both old and new. It is interesting to note that some of the most well-known innovators, including Warren Buffet, who dedicates 80% of his day to reading; Bill Gates, who reads 50 books a year; Mark Cuban, who reads 3 hours a day; and Elon Musk, who learned how to build a rocket by reading, see reading as foundational to their success. [1]

1.6.1.1.2 Reading Online

Browsing the internet and reading online are great ways of staying current, but they do come with their own set of unique problems, primarily because the way we read online is very different than the way we read a printed text. Fortunately, there are strategies for reading productively online.

1.6.1.1.2.1 How Reading Works

1.6.1.1.2.1.1 Transactive!

Reading is a “transactive” process. That just means there is a transaction, an exchange going on between your brain and the text. Neuroscientists say that 10 times more information is being sent from the prefrontal cortex than is being received from the text.

1.6.1.1.2.1.2 Filling in the Blanks

We read words like they are a gestalt – that just means we look for patterns and fill in the blanks to save time. You might have seen the following example, which you can probably read with ease even with many of the letters missing from each word:

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteers be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.”

1.6.1.1.2.1.3 The Phenomenology of Reading

phe·nom·e·nol·o·gy

/fəˌnäməˈnäləjē: an approach that concentrates on the study of consciousness and the objects of direct experience.

Maurice Merlieu-Ponty, a phenomenologist, says that when we read we look through the letters to the image the words evoke – the words themselves almost seem invisible.

1.6.1.1.2.1.4 Saccades and Fixations

We read in a jerky motion, really focusing on only one word and a few that surround it before jumping to the next. In eye-gaze studies of how we read, the distance we jump is called a saccade, and the word we focus on is called a fixation. When we read a print textbook we “fixate” on about 60% of the words, whereas when we read an online textbook we only fixate on about 30% of the words.

1.6.1.1.2.2 Problems with Reading Online

We approach the online environment with a different purpose in mind – usually one that involves finding some immediate gratification. In this case we might be too focused on the destination to pay attention to the details of journey itself.“People who read text studded with links, the studies show, comprehend less than those who read traditional linear text.” -Nicholas Carr

When we read online, we are likely to be actively searching for shortcuts that will get us from where we are to the information we seek in the shortest amount of time.

If the reader has little motivation, any distraction becomes that much more powerful. Reading a textbook can be dry and boring, so it takes a motivated reader to stay focused. In an online environment, something more flashy and interesting is only a click away.“The sense of touch in print reading adds an important redundancy to information – a kind of “geometry” to words, and a spatial “thereness” for text” – Maryanne Wolfe

Eye tracking studies suggest that we default to an F pattern when presented with the most daunting online information: The Wall of Text. That just means that we tend to read the first line word-by-word, but then as we get further down the page we may only read halfway across the page, and then at the very end, if we have found nothing that really catches our attention, we read maybe only the first word of the last line before we move on. The end result is that a whole region of text that could contain important keys to understand the other region is left unseen.

1.6.1.1.2.2 The SIRI Strategy

Some of the problems above can be mitigated by using the following strategy.

- Scan: Determine your purpose and scan the reading as you normally would.

- Identify: Identify any links or other opportunities that look promising, in addition to any words that you don’t understand.

- Read: Read all the text from left to right. Minimize any distractions. You can print the material out or use the Mercury Reader extension to Google Chrome to format the page for reading. Use the commitment pattern* here.

- Interact: Now review the links, videos, or other opportunities for interaction and prioritize them according to your interest.

To add a tactile component to your online reading, it also helps to take notes in a paper notebook as you go.

*The commitment pattern consists of fixating on almost everything on the page. If readers are highly motivated and interested in content, they will read all the text in a paragraph or even an entire page (Pernice).

1.6.1.2 General Watching/Listening

Netflix, documentaries, broadcast news, sitcoms, podcasts, and YouTube videos are all fine places to learn new stuff. You may have other places you like to go to find audio or visual material. This works best if you keep your watching and listening fairly random and avoid excluding sources you may hold unconscious biases against or that are out of your comfort zone. In other words, try new stuff.

1.6.1.3 General Conversation

Talking with people in all walks of life expands your thinking geographically, ethnically, economically, and socially.

1.6.1.4 General Observation (people watching)

Human beings spend more time than we realize watching other people. From the time we are born, observing other people is how we learn how to behave in public, and what is appropriate or not appropriate in a given situation. Writers should pay specific attention to it.

1.6.1.5 Think in the Future Tense

Living in the present is a great thing. Some say that is where we should focus all our attention. However, basic survival does require us to spend some minimal amount of time reflecting on the past and planning for the future. Just thinking about the future of humanity every once in awhile will help keep you current.

1.6.2 Time Management

If you are not a full-time writer, you have a lot of other stuff that needs to get done ASAP. For this reason, being an effective part-time writer means you have to be an effective manager of your time.

1.6.2.1 Quantitative and Qualitative Tasks

The first item you need to be aware of to fit writing time into your schedule is that it is a qualitative and not a quantitative task, and trying to make it into a quantitative task is a recipe for failure. Here the words qualitative and quantitative are being deployed in a slightly different way than they are in the Memory: Intertextuality I chapter. By a quantitative task, I mean a task that can be checked off a list without setting aside too much time for it. The following are quantitative tasks:

- Buy milk

- Pay electric bill

- Cash paycheck

- Get mail

- Mow lawn

- Plant flowers

By qualitative task, I mean a task that 1) can’t be completed in one episode, 2) has no clear time boundaries (it might take 5 minutes or 5 days, and 3) requires the full concentration of the person working on it. The following are qualitative tasks:

- Learning to play “Stairway to Heaven” on the guitar

- Practicing Spanish

- Meditating

- Reading

- Researching

- Writing

The type of task can be pretty easily determined by the tense of the verb in the verb phrase, which for quantitative tasks is the present tense, suggesting it is going to happen immediately and be done, and for qualitative tasks is the present participle, suggesting that it is an ongoing action. The quantitative tasks can be completed as fast as you can get to them, whereas a qualitative task can’t be done any faster or slower, regardless of your motivation. Imagine going to a concert, for instance, and trying to finish listening to the concert as quickly as you possibly can so you can get to the store and buy milk on time, or meditating as quickly as possible so you can pay the electric bill.

1.6.2.1.1 The Carnegie Rule

Unfortunately, neither writing an argumentative research essay nor getting a college education can be treated the same as buying a gallon of milk.

The Carnegie Rule , around which most college classes are designed, suggests that in order to get the best results, you should plan on setting aside 2-3 hours per week outside of class for every hour you are in class. That means that a 3 credit hour class will take up 9-12 hours per week. The same is true for an online class, since you should still spend 2-3 hours per credit hour per week in addition to the hour you set aside for each credit hour for the asynchronous activities like discussion boards, videos, and quizzes that are meant to replace in-class activities.

An argumentative research essay should take about 6 hours per page once you include the time spent doing exploratory research, narrowing your topic, researching your audience, crafting a thesis, reading sources, engaging in primary research, writing an outline, and actually writing the text of the essay itself. Knowing that, your should calculate how much time you need to spend each week on the essay by working back from the due date and actually scheduling time to include at least enough time each week to reach the number of hours by the due date. It is okay that some of those hours go unproductive, since even staring at a blank page for an hour and a half counts. Writing is like that. Using the formula of 6 hours for every page, if you have a 10 page essay due in 10 weeks, you will just need to make sure you set aside about 6 hours a week for writing the essay.

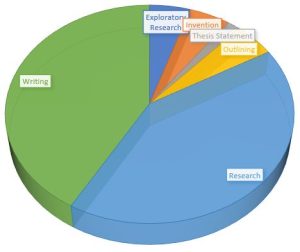

Here is what a breakdown of your time might look like if you spent your 60 hours (assuming a ten page paper):

- Exploratory Research = 3 Hours

- Invention = 3 Hours

- Thesis Statement = 1 hour

- Outlining = 3 Hours

- Research = 25 Hours (Assuming a reading rate of 9 pages per hour)

- Writing = 25 Hours (Assuming a writing (drafting, revising, proofreading) rate of 1 page per 2.5 hours)[2]

The distribution of these writing tasks will obviously vary depending on the specific project and the writing style of the writer, but the time estimates above are fairly typical.

1.6.2.2 Methods of Time Management

1.6.2.2.1 The Eisenhower Matrix

The Eisenhower Matrix method was used by Dwight Eisenhower both as a an Allied Forces Commander in the U.S. Army in World War II and as President of the United States. Here is how it is done:

- Make a list of all the tasks you need to complete.

- Organize them according to the matrix below

- Urgent/Important (Do now!) tasks are those that need to be completed ASAP, like getting to class on time, submitting a paper that is due, or paying your taxes. In most cases, these are quantitative tasks.

- Not Urgent/Important tasks (Schedule!) are takes that are more related to your long term goals and values, like reading, learning to play the guitar, spending time with a friend, or writing an argumentative research essay. In most cases, these are qualitative tasks.

- Urgent/Not Important (Delegate) tasks are things that need to get done immediately, but that don’t really contribute that much to your long term goals. Buying socks might be one of these. Eisenhower was in a leadership position and had underlings he could delegate tasks like this to. You may not have minions to buy your socks for you, so you will probably have to do it yourself. You will have to be your own minion, so you could set aside a time to do minion-like tasks.

- Not Urgent/Not Important (delete) tasks are tasks you can either ignore or get rid of. Get rid of them. They should not occupy your consciousness at all.

If you spend the most time and effort in the Important/Not Urgent quadrant then there will be fewer and fewer items that slip into the Important/Urgent quadrant. An argumentative research essay in a composition class is a great example. If you spend a lot of time and effort working on it as an important but not urgent task then it won’t slip into the important and urgent quadrant the day the essay is due.

1.6.2.2.2 The Pomodoro Method

The Pomodoro Method was created by Francesco Cirillo, and it operates on the principle that most people can focus intensely on projects for a short period of time, as long as they take short breaks in between. It is named after the Italian word for tomato, which was what the timer the inventor used looked like. Here is how it is done:

- Select a task

- Set a timer for 25 minutes.

- Work on the task until the timer goes off.

- Take a five minute break.

- Repeat 4 times from step 2.

- Take an extended break.

- Repeat as necessary.

16.2.2.3 The Parkinson’s Crunch

The Parkinson’s Crunch method is named after Parkinson’s Law, which suggests that work expands to fill whatever time has been allotted for it. The Parkinson’s Crunch method takes advantage of that law by restricting the time available to complete tasks, knowing that more energy will be focused toward completing them. If you apply this law to the quantitative tasks, and leave the time allotted the same for the qualitative tasks, then you will hopefully find that you have more time for the qualitative, or important/not urgent tasks.

1.7 Pathos and the Writer

Some moods or emotions can hinder good writing, while others seem to help. Some writers are motivated by anger, others by passion, and still others by compassion. You may have your own mood you like to foster for writing, but for the purposes of the argumentative research essay, it is probably best to sustain a mood of disinterestedness. Remember from the Time Management section that a ten page argumentative research essay is likely to take about 60 hours to research and write, and moods like anger, passion, and excitement are difficult to sustain for that length of time. A disinterested stance, which is not to say uninterested, is not only much easier to maintain, but it is also the mood most conducive to an academic argument. The reason for that is that, as mentioned in the pathos chapter, emotional content that is too strong or obvious can raise red flags in a reader’s psyche and have a negative impact on their perception of the writer’s ethos. A disinterested stance is nearly synonymous with the absence of emotion, and that is the most effective platform to make a reasoned argument from. Granted, passion is sometimes persuasive in itself, but like all arguments from pathos, is quickly wears of if the argument is not sound. Thus, a healthy disinterestedness or dispassion is a more sustainable platform for argument both for the writer and the audience, as it highlights the logos, which is absolutely critical for the persuasive effect to last.

Licenses

The section “Cognitive Biases” contains derivative material from “List of Cognitive Biases” at www.Wikipedia.org licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. Please visit the site for further attribution by any cognitive bias you are interested in.

- https://www.inc.com/marissa-levin/reading-habits-of-the-most-successful-leaders-that.html ↵

- These numbers obtained from the Rice University course workload estimator located at https://cte.rice.edu/workload. ↵

A brief, rapid movement of the eye from one position of rest to another, whether voluntary (as in reading) or involuntary (as when a point is fixated)(OED)

The concentration of the gaze upon some object for a given time with the intention of holding the retinal image upon the area of direct vision (OED).

A large block of only text that is not broken into chunks or broken up by visual information.

unbiased or impartial

bored or indifferent