10

Coming up with Stuff to Say

9.1 Overview of Invention

One of the most common afflictions of the student of English Composition is the belief that she has nothing to say. Often it only afflicts her in front of a blank screen with a paper due at midnight, but is miraculously remedied in the company of good friends, when she suddenly becomes prolific on all sorts of topics. Invention can be as simple a matter as channeling that social expert into the mode of writing a paper.

The obstacles to invention, which can include evaluation apprehension, sleep deprivation, and lack of information on a subject, “Who is more to be pitied, a writer bound and gagged by policemen or one living in perfect freedom who has nothing more to say?” ― Kurt Vonnegutcan sometimes be overcome by brainstorming activities like freewriting, idea mapping, list making, conversation, and reading. The most important rule to observe in the stage of invention, before you have any solid ideas, is to suspend judgement. This is particularly important in list making and freewriting, where the purpose is to generate as many ideas as possible. The culling and trimming of those ideas will come in due time, but should be avoided at a time when creativity is most important.

Brainstorming is simply listing everything you can think of about a particular topic. Freewriting is sitting down and writing what comes to mind when thinking about a particular topic without judgement. Reading and browsing the internet can also be effective tools for brainstorming, provided you don’t get lost on the internet and find yourself in some world where people post nonsense as a substitute for real social activity. In that regard, informal discussions, class discussion, and discussion boards can also be generative.

Because writers can have numerous ideas on a topic that are all jumbled up and don’t fit together, like a messy room, arrangement and invention are closely related. Invention is like coming up with all sorts of ideas and throwing them out on the floor without care, like one’s shoes and socks at the end of a long day, while arrangement is the sorting and straightening out of those ideas, and necessarily involves throwing out the useless stuff.

9.2 Invention Techniques

The invention techniques that follow are arranged in a rough order and can all piggyback on one another. If you aren’t writing for a particular occasion with a predefined topic and a known audience, then a good place to start is to figure out what interests you. Once you have figured out a few things that interest you, you can use some of those general interests to create a new list of related items. For example, if one of your interests is animals, then you could move to the next step of list-making by making a list not only of different animals, but of anything you could think of that is related to animals, including perhaps hunting, preservation, animal husbandry, animal shelters, and petting zoos. So first notice how the following techniques can build off one another, just like the list can build off of the interest inventory, and the concept map, in turn, can build off the list by taking its central term from the list.

The next thing you might notice is that while the idea behind invention is to come up with as many ideas as possible, it still proceeds not from pulling as many random ideas out of a hat as you can, as a magician might do with rabbits and ribbons and other objects, but from splitting bigger, more general topics into smaller topics. That seems counterintuitive, but in a world where so much has already been said, the hardest part is to figure out what hasn’t yet been said. In some sense, it is like joining a conversation, where the process of invention occurs dynamically and is often just a matter of split-second decisions. Before speaking up, each participant in a conversation must think about everything that has thus far been said, and what he can possibly say that hasn’t already been said. If a participant in a conversation simply repeats what the last person said he isn’t really being inventive at all, right?

While the very first step of invention might be like pulling a random idea out of a hat, once you pull that thing out of the hat, the goal is to try to figure out everything that can be said about that one thing that hasn’t already been said. Maybe the magic hat is the hat that contains all your interests, and once you pull something out, then it is a matter of using the fishes and loaves technique to create new stuff from that one little thing. I’m referring here to the story of the five loaves and two fishes that Jesus was said to have used to feed the multitude. Invention is more like that: you start with a loaf of bread. That is all you have. You can’t go bigger than everything that it is possible to say. The miracle of invention is coming up with original stuff to say from just that one loaf of bread. Thus, really, the fishes and loaves technique of splitting something into as many pieces as possible, as miraculous and difficult to comprehend as it is, is the more apt metaphor for how invention occurs. Invention is creating by breaking apart.

That is the order in which the following techniques proceed, and the difference between the basic and the advanced techniques is primarily that the advanced techniques are working from smaller and smaller pieces. By the time you get to the five whys technique or the topoi questions, you have already identified a pretty small piece of bread to work from, until finally you arrive at a thesis statement that makes a new and original claim.

One last thing. Although the techniques below are listed in an order that proceeds from very general idea generation to more specific and precise splitting, that in no way means you have to start at the beginning. You can start anywhere. If you see a method you like, you can start there. And because you will be revisiting the house of invention regularly, some techniques might be useful at the beginning stages of your essay, while others might be more useful at later stages.

9.2.1 Basic Techniques

9.2.1.1 Interest Inventory

At the beginning stages of deciding on a topic, you might want to start with listing things that interest you. The sky is not only the limit, it, can be included along with anything else you might be curious about such as sports, music, writing, reading, skateboarding, climbing, or what have you. If you are lucky, many of your interests might line up with your career, and some probably will line up with the course of study you have chosen. You can find other topics by thinking about what you choose to do when you have free time. For instance, you could begin by asking yourself the following questions:

What do I want to read about?

What kinds of things do I watch on television?

What games do I like to play?

What are some recent internet searches I did?

What issues am I passionate about?

What news did I recently hear that caught my interest?

What do I want to know more about?

What subjects are most engaging for me in school?

What am I good at?

If I could make any policy into law, what would it be?

Whom do I most admire? Whom do I least admire?

What do I love? What do I hate?

What am I concerned about?

What makes me happy?

If you are still having trouble with a list, see if you can find something on the list below that interests you or that you would like to know more about:

9.2.1.1.1 List of Interests

If you are still having trouble with a list, see if you can find something on the list below that interests you or that you would like to know more about:

A

Acro yoga, Acting, Aerial silk Airbrushing, Airplanes, Aliens, Amateur radio, Anarchy, Animals, Animation, Aquascaping, Archeology, Architecture, Art Astrology Astronomy, Axe-throwing

B

Babysitting, Baking, Basketball, Baton twirling, Beatboxing, beertasting, Bigfoot, Binge-watching, Biology, Blogging, Board/tabletop games, Boating, Book discussion clubs, Book restoration

C

Cats, Calligraphy, Candle making, Camping, Candy making, Car fixing & building, Car racing, Card games, Cardistry, Ceramics

D

Dance, Debate, Decorating, Digital arts, Dining, Diorama, Distro Hopping, Diving, Djembe,

E

Economics, Electronic games, Electronics, Embroidery, Engraving, Entertaining, Experimenting,

F

Fantasy sports, Fashion, Fashion design, Feng shui decorating, Filmmaking, Fingerpainting, Fishkeeping, Fishing, Flower arranging, Fly tying, Football, Foreign language learning, Four-Wheeling, Furniture building,

G

Gaming (tabletop games, role-playing games, Electronic games), Gambling, Gardening, Genealogy, Geocaching, Geography, Geology, Gingerbread house making, Giving advice, Glassblowing, Gongoozling, Graphic design, Graffiti, Gunsmithing, Gymnastics,

H

Hacking, Hardware, Herp keeping, Home improvement, Homebrewing, Houseplant care, Hula hooping, Humor, Hunting, Hydroponics

I

Ice skating, Inventing

J

Jewelry making, Jigsaw puzzles, Journaling, Juggling,

K

Karaoke, Karate, Kendama, Knife making, Knitting, Knot tying,

L

Lace making, Landscaping, Lapidary, LARPing, Leather crafting, Lego building, Linguistics, Livestreaming, Listening to music, Listening to podcasts, Lock picking

M

Machining, Macrame, Magic, Makeup, Marxism, Massaging, Mazes (indoor/outdoor), Meaning, Meaning of life, Mechanics, Meditation, Memory training, Metalworking, Miniature art, Minimalism, Model building, Model engineering, Music, Mythology, Mythological creatures Movies

N

Nail art, Nature, Needlepoint,

O

Origami,

P

Painting, Palmistry, People, Performance, Pet, Pet adoption & fostering, Pet sitting, Philately, Philosophy, Photography, Pilates, Planning, Plastic art, Playing musical instruments, Poetry, Poi, Postcrossing, Pottery, Powerlifting, Practical jokes, Pressed flower craft, Proofreading and editing, Proverbs, Psychology, Public speaking, Puppetry, Puzzles, Pyrography,

Q

Quilling, Quilting, Quizzes

R

Radio-controlled model playing, Rail transport modeling, Rapping, Reading, Recipe creation, Refinishing, Reiki, Relationships, Reviewing Gadgets, Rocks, Robot combat, Rubik’s cube

S

Sailing, Scrapbooking, SCUBA Diving, Sculpting, Sewing, Shoemaking, Singing, Skatebboarding, Sketching, Skipping rope, Slot car, Soapmaking, Socialism, Social media, Space Travel, Spreadsheets, Stamp collecting, Stand-up comedy, Storytelling, Sudoku

T

3D[SGE1] -printing Tattooing, taxidermy, telling jokes, thrifting, tiny houses, traveling, television, Table tennis playing, Tapestry, Tarot, Tattooing, Tatebanko, Tattooing, Taxidermy, Telling jokes, Thrifting, Tiny houses, Traveling,

V

Video gaming, Video editing, Video game developing, Video gaming, Video making, VR Gaming,

W

Wargaming Waxing, Weaving, Web-design, Webtooning, Weight training, Welding, Whittling, Wii sports, Wikipedia editing, Wine tasting, Winemaking, Witchcraft, Wood carving, Woodworking, Word searches, Worldbuilding, Writing, Writing music

X, Y, Z

Xylophones, Xenophobia, Yoga, yoyoing, Zumba

Whatever your interests may be, making a list of 10-20 of them is a great place to start when you are given the option to write about anything. And remember, at the beginning stages of invention you are just looking for broad categories of interest. Later, you may already have a narrowed topic, in which case you can use some of the more advanced techniques of invention to discover distinctive perspectives for your topic. Working from a unique angle affords you a chance to add something new to the conversation you are joining through your writing.

9.2.1.2 The List

The most basic form of brainstorming or invention is the simple list. There is nothing fancy here – just make a list of all the ideas you have regarding a general topic. You no doubt have more subject options now that you have made a list of your interests. It just so happens that you can choose any one of those interests and make a list of items or topics that you associate with that particular interest. Now is a good time to choose three, and then maybe make a list of associations or possible topics that come out of each of the interests you listed. Take your list of interests and put them in order leading with the things that at this moment interest you the most to the things that at this moment interest you the least. Take the top three and make a list of topics from each of them.

Here is how it is done:

- Take out a sheet of paper, open your favorite notetaking app, or make an entry in a notebook you keep for the purposes of recording your ideas.

- Make a list of all the ideas you have about your topic.

- Remember, anything counts, so if “Fruity Pebbles” ends up on your list, that’s okay. You are trying to come up with as many items as you can, so for the moment, “Fruity Pebbles” counts. You might consider, as a matter of course, inserting “Fruity Pebbles” into any list you make just to remind yourself that anything goes at this stage.

- See what you can use and either run with it or bring it with you to the next stage of the invention process.

List Example

9.2.1.3 Concept Map

The concept map is really just a more visual way of making a list, and as such it does two things better than the list: (1) It shows the associations between list items, and (2) it allows for nearly endless branches of associations. There are several websites, apps, or computer programs that allow writers to create concept maps electronically, including Mindmeister, Mindmup, Freemind, and Wisemapping, but there is always that standby, pencil and paper, which works extraordinarily well for this purpose.

To create a paper-based concept map:

- Identify a central concept in one word which will serve as the primary node for your idea map. You can build upon your list by taking your central concept from there.

- Put your central concept or word in the center and draw a circle around it.

- Use free associating to think of the first word you associate with the central concept. In other words, look at the word and say the first word that comes to mind (this works well in groups, also). Write that word in a circle and connect it with a line to the central concept. Maybe you will repeat this several times before creating a branch, which is where the real power of this technique exists.

- To create a branch, take one of the words you have associated with the central concept and use it as a new starting point, trying to think of words you associate with that concept instead of the one you started with originally. Always draw a circle around the word and connect it to the associated word circle with a line.

- To create another level of branching, use one of the words you associated with the new starting point as a new starting point. Just imagine it like a word tree, with your first central concept as the trunk, each new starting point as a branch, and additional starting points as branches from branches. You could even draw it like a tree if that helps. Keep going until you have filled the page.

- Draw some arrows between words that seem related to one another, even though they may be across the page and come from very different branches. This is called cross-branching, and it can yield some surprising relationships related to your original central concept. You also may find that the further you branch out, the weirder it gets, and you may wonder how you ever got from Fruit Loops to the Nile River. But this is precisely the power of the concept map. In the stage of invention, weird is what you are looking for.

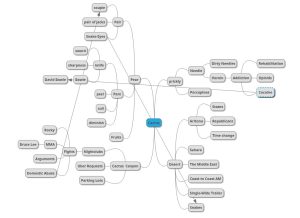

Example: Concept Map

In the above illustration note that some concepts captured on the map are related in some way, despite their having come from different branches. Three examples are domestic abuse/couples, David Bowie/cocaine, and snakes/snake eyes, but there are likely many more. You may also note that the further away the branches get, the less explainable their connection. For instance, how the heck did we get from cactus to Bruce Lee? The true generative power of the concept map is in these weird connections. Often, they prove to be dead ends, but just as often you will discover something new about your topic by following them.

9.2.1.4 Freewriting

The use of freewriting as a single word indicates a specific technique belonging to the larger category of free writing. That is, there are other types of writing that are free. Poetry comes to mind. But freewriting is not poetry, necessarily, nor is it nonsense writing or any of the other forms of writing with minimal rules. Freewriting is something much more specific, and it only has one directive: don’t stop writing.

To Freewrite:

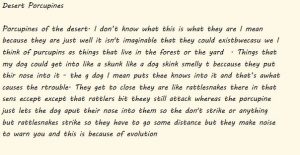

- Find a prompt that is related to a topic you want to be thinking about. This could be a word from your list, a word from your concept map, a phrase, or a question. One especially powerful prompt is to piggyback your freewriting on the concept map and pick two of the most unusual or particularly interesting concepts that you discovered there for your prompt. From the above map, it might be “desert porcupines” or “single-wide trailer Uber request.” Random word pairs you can find that are in the territory of your idea map are sometimes the best.

- Stop thinking.

- Set a timer.

- Start writing.

- Don’t stop writing for any purpose until the timer expires. Don’t stop to think, revise, or correct anything.

Example: Freewriting

9.2.1.5 Looping

Looping is an extension of freewriting that builds upon a previous freewrite and expands on any particularly interesting or salient concepts that the writer might have noticed in the first freewrite. Notice in the below example that we somehow have returned to the rattlesnake by discovering similarities between the porcupine and the rattlesnake, particularly their pointy defense mechanisms, and maybe more importantly, the relative passivity of their defense mechanisms:

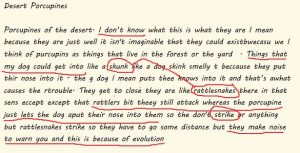

Example: Freewrite with Interesting Phrases Underlined

This example shows the underlined phrases that seem particularly relevant or interesting and circled words that might be relevant. Some words that are in some way complementary have been connected as well, particularly, rattlesnakes and skunks, who also have similar defense mechanisms in common with the porcupine. None of these creatures is likely to aggressively seek out a victim to ply their defensive mechanisms; in fact, all their defense mechanisms aren’t triggered until a potential threat is too close. If I chose then to use “[Rattlesnakes] make noise to warn you” as a prompt for my next freewrite in a series, I might get closer to the message behind the Gadsen Flag and it’s coiled rattlesnake captioned “Don’t Tread on Me,” which turns out to be important to my understanding of the Rattlesnake Buttes and the Colorado Militia that in James Michener’s novel, Centennial, attacked a defenseless Indian camp there.

Here’s how it’s done:

- Take an existing freewrite and underline the phrases that seem interesting to you or relevant to your thinking on a topic. Circle words that stand out, and if possible, draw a line between words that seem like they might be related.

- Choose one of these phrases, words, or word pairs to use as the prompt for another freewrite.

- Repeat the freewriting process described above until done.

9.2.1.6 The Key Drop (or the Bucket Drop)

Salvador Dali is reported to have used the key drop technique to come up with ideas for new inventions while EInstein, Edison, and other inventors used similar techniques. The key drop method takes advantage of the theta brainwaves we usually enjoy on the fringes of sleep, either as we are just falling asleep or just waking up. These are often very creative times, and nearly as often ignored. The moment the key drops from your fingers, you may be sure that the noise of its fall on the upside-down plate will awaken you, and you may be equally sure that this fugitive moment when you had barely lost consciousness and during which you cannot be assured of having really slept is totally sufficient, inasmuch as not a second more is needed for your physical and psychic being to be revivified by just the necessary amount of repose. -Salvador DaliThe key drop method involves sitting in a chair and holding a key loosely in your hand above a china or metal plate and letting yourself doze off. When you doze off, you will relax your hold on the key and it will fall onto the plate, creating a noise that will wake you. Depending on your unique physiology, you will then enjoy 3-5 minutes of your most creative state of mind. If you have a pen and notebook handy, you can write down your most ingenious thoughts and impress your friends and neighbors later with your creativity. Or sometimes not. Here is how it is done:

- Gather your materials: a chair, a pen, a notebook, a key, and a china plate (or alternately, a rock and a metal pail if you find yourself not waking up to the key dropping against the plate. Ball bearings or marbles, according to Thomas Edison, might work as well)

- Sit down in the chair and write a word you want to focus on in your notebook. This could be a single word from one of the basic invention techniques you tried earlier, a two word combination, or even a sentence.

- Place the notebook and pen safely on your lap or on a nearby surface.

- Place a plate on the floor and hold a key loosely in your hand while you doze off.

- When the noise of the key dropping onto the plate wakes you up, pick up your notebook, look at the word or words you wrote down earlier, and write whatever comes to mind.

9.2.1.7 Freedoodling

Here is a way to attack a linguistic problem with a non-linguistic tool. Sunni Brown, in her book The Doodle Revolution, calls doodling a “visual language.” She makes a great case for using doodling to come up with great ideas and provides some practical advice on how to implement specific strategies including atomization, game -storming, and process mapping. To these can be added cartographical ideation, which is just a fancy phrase for drawing a map of your ideas like they were cities, rivers, mountains, bridges, and so forth.

9.2.1.7.1 Atomization

Atomization involves drawing the most basic parts of an idea without putting them together to make a consistent whole. If I were to atomize a rattlesnake, for instance, I might draw a baby rattle, a pair of dice with snake eyes, some thorns for the fangs, a snakeskin belt, and whatever else I could think of – maybe a pit for the pit in viper. The representations don’t have to be metaphorical like that. You can draw a real rattle, real snake eyes, real fangs, and so on, if you are inclined. You can also draw the components of abstract concepts like “spirituality” or “fear.”

9.2.1.7.1 Game-Storming

What Brown calls “Game-Storming” is the creation of a kind of chimera. Basically, atomize two different concepts and then combine them in new and fanciful ways just to see what you come up with. An example that is animalistic in nature creates a clear picture of the concept. Visualize an animal that is a striped rattlesnake with a skunk’s tail and porcupine quills all over it. This can be done with abstract concepts as well. For instance, try to draw “spirituality” and “erosion,” then recombine them in unusual ways visually.

9.2.1.7.2 Process Mapping

Process mapping is a way of diagramming social, geological, economic, or other operations visually. Flowcharts with shapes representing various actions or logical operators can alsoThe whole world is a series of balanced antagonisms. -Ralph Waldo Emerson be created. Circles representing cyclical movements can often be helpful. A “balanced antagonism” could be represented by a flat line perched atop a triangle to represent a teeter-totter.

9.2.1.7.3 Cartographical Ideation

This doodling technique, like many of the others, uses spatial thinking to inform the more linear process of writing. Cartographical Ideation is the drawing of a topographical map that uses symbols for mountains, rivers, highways, bridges, cities, farms, fields, lakes, and the like to represent concepts, ideas, data, and flows in a scale that can show their relative importance to one another and relative solidity of the connecting ideas in a way a simple outline cannot. You can, for instance, use major cities to indicate main ideas, smaller outlying cities to represent smaller, connected ideas, bridges to represent connections between ideas, and rivers or highways to represent flows from one idea to the next.

One interesting variation on this is to take an existing map, like a map of ancient Egypt for instance, and just replace the names on the map with concepts or ideas related to your topic. Like the concept map and the list, this technique can grow with your project, taking you from the House of Invention to the House of Arrangement and beyond.

9.2.1.8 Walking

William Wordsworth’s collection of poems is said to have cost him somewhere around 180,000 miles on foot. That’s some serious walking, but Wordsworth also had some serious and prolific creativity. Sweet was the walk along the narrow lane/At noon, the bank and hedge-rows all the way/Shagged with wild pale green tufts of fragrant hay/… Musing, the lone spot with my soul agrees. -From “Sweet was the Walk” by William WordsworthNote Wordsworth’s line about “musing” – what is that? I’ve mentioned the muse, which is a singular version of the nine muses in Greek mythology, but Wordsworth uses it here as a verb: musing. It is interesting to note that, as a noun, it can refer to the nine Greek goddesses, all daughters of Zeus, who are charged with putting ideas into people’s heads, but as a verb it is roughly comparable to wasting time in thought, which is, counterintuitively, a more active way of coming up with ideas than waiting for some mythological goddess to put them there. The long and short of all this is that there is much to recommend actively musing, and this is what we should be doing when we go for this kind of walk , which by its own nature leads us nowhere.

To be brief, here is how it is done:

- Take a twenty minute walk with no set destination.

- Muse.

Like the other methods of invention, the rewards that come from walking aren’t always immediate. Going for a walk doesn’t mean you will come back with an idea. Even for Wordsworth, who was known as “the walking poet,” not every walk translated to some stroke of genius. However, a recent Stanford University study suggests that walking can boost creativity by up to sixty percent – and the benefits of divergent thinking gained from walking don’t stop when you stop walking.[1] The benefits continue long enough to carry you through after you have sat down in front of your computer screen again. Now, while this study suggests that walking jump starts creativity whether you do it on a treadmill in front of a blank wall or outside in a park or on a trail, there is always the added benefit of seeing new stuff once you head outdoors.

9.2.1.9 Water-Gazing

I mention this here because it is so closely related to walking. The principle is the same: If I muse but two houres on the bankes of the Tyber, I am as understanding as if I had studied eight days. – J.L.G. de Balzacset aside a block of time to actively do nothing. In this case, do it by a river or other body of water. If you find it difficult to find the time to do nothing in your schedule, consider de Balzac’s formula: 2 units of water-gazing = 64 units of studying (assuming 8 hour days).

Briefly, here is how it is done:

- Procure a chair (optional).

- Find a river or body of water.

- Face the water and sit down.

- Muse.

Fire-gazing, star-gazing, and rain-watching are all variants of this technique.

9.2.2 Community Brainstorming

9.2.2.1 Overview of Community Brainstorming

Any of the preceding methods of invention can be used effectively in a group setting. It is good to have one person, ideally the writer, taking notes on a device, on a sheet of paper, or on a whiteboard. It is important to foster a mood of non-judgement in this community, whether it be a small community of 3-5 people or a larger community At this stage in the creative process it is counterproductive for any participants to comment, sneer, roll their eyes, or otherwise denigrate any idea that comes up, even when it may sound weird or unrelated to the topic. As with all modes of invention, criticism is poison gas – it will stall the process where it stands. At its best, group brainstorming is like that moment when you[link to general you in style] are cooking microwave popcorn, or any other sort of popcorn, really, and the kernels are popping so frequently that it creates a general roar. At the beginning, a few people might spit out ideas, but when the process gets going the ideas should be coming faster than you can write them down. For that reason, it might be a good idea to record the session with a digital audio recorder or a smart device.

9.2.2.2 Alphabet Game

- Choose a word or phrase to serve as a prompt.

- Gather a group of 3-5 people.

- Each participant, including the rhetor, should take out a sheet of paper and write the letters of the alphabet in a column or two.

- Each participant should take five minutes to match each letter with a word they associate with the prompt.

Example: Alphabet Game

9.2.2.3 Two-Word Invention

- Choose two words relevant from your topic. This works best if you choose words from one of the other invention techniques like list-making, idea-mapping, or even the alphabet game above.

- Collaborate with a partner to create an invention based on the two random words you have chosen. For example, if I chose “warning” and “mouse” from the above example, I might invent either a warning mouse or a mouse warning, both useful inventions with similar purposes. Note that if you want to, you can change the form of the words to suit your purposes. So if you have two nouns, you could change one to an adjective, or you could change a noun to a verb, or you could change adverb to an adverb – you get the idea. In the previous example, for instance, I could change mouse to mousy, thus creating a whole new kind of invention that might warn someone of a break-in with a high-pitched squeaking noise.

- If you can, try to pitch your invention to a willing audience.

Example: Two-Word Invention

This may seem rather farcical at first, but as with all invention techniques, the point is to purposefully see your topic in a different light. It might cause a light bulb to turn on inside your head. If it doesn’t, try another technique!

9.2.2.4 Freewrite and Share

- Find a group of 3-5 willing participants.

- Assign every participant the same word selected the list, idea-mapping, or alphabet game techniques of invention. Ask each participant to use the freewriting technique to write for five minutes using the provided word as a prompt. Alternately, you can give each participant a different word from the list to use as a prompt.

- Ask each participant to read their freewrite just as the wrote it.

- Discuss the results. What were some similarities in the freewrites? What were some differences? Try using the synthesis techniques described in the Memory chapter to bring everything together. If the participants are willing, have them each write their own synthesis of the freewrites.

- Collect all the writings of your group members to refer to as you continue to cultivate ideas.

Ethos: Fair-mindedness. Understanding and engaging with multiple voices from the outset will make you appear more fair-minded to the audience.

Invention: Angle. Community brainstorming activates a dialogical process by engaging many voices and unique experiences to add a depth of originality to your thinking at the outset, and can alert you to unusual or interesting angles on the topic. This, in turn, is more likely to engage diverse audiences.

Memory: Dialogical Thinking. Hearing many different ideas from different people engages your own dialogical thinking on the idea. Even if the idea you finally settle on seems straightforward, it is [a product of…].

- https://www.healthline.com/health-news/walking-indoors-outdoors-increases-creativity-042814#Walking-Increased-Creativity-by-60-Percent ↵

Drawing a topographical map of geographical features like mountains, rivers, highways, cities, bridges, etc., to represent concepts, ideas, and flows of information.

A fabled fire-breathing monster of Greek mythology, with a lion's head, a goat's body, and a serpent's tail (or according to others with the heads of a lion, a goat, and a serpent), killed by Bellerophon, or more figuratively, An unreal creature of the imagination, a mere wild fancy; an unfounded conception (OED)

Contrary to intuition; that is opposed to or not what would be expected intuitively; apparently improbable. Also, that acts or responds in such a way.

Thinking about or solving a problem in a way that is uncommon or differs in important ways from the usual solutions.

Resembling farce; extremely ludicrous; that is matter only for laughter; absurdly futile.