18

Remembering, Referencing, and Integrating Source Material

17.1 Integrating Source Material

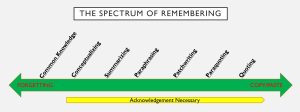

There are three primary ways of integrating source material into an essay: summarizing, paraphrasing, and quoting. Although these are the primary modes of referencing source material, it is also sometimes useful to think of this referencing on a spectrum on one end of which is forgetting the material completely, and on the other end of which is copying it word for word. At most of the stages, it is important to acknowledge where the information came from, especially in societies where scholars and writers depend on their ideas for their livelihood.

17.1.1 Forgetting

Really, what you forget is just as important to your final essay as what you remember. If you purposefully forget valid information that is contrary to your argument, then that is a red flag for some audiences and will negatively affect your ethos. On the other hand, if you forget the spurious, the invalid, and the strongly biased, retaining only the most credible and fair-minded sources, then this will positively affect your ethos. Refer to the previous chapter for systematic methods to determine what to remember and what to forget for the purposes of a particular argument.

17.1.2 Common Knowledge

Most people remember that water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit and that water boils at 212 degrees, but not everyone remembers where they learned that at. Such things are common knowledge, so you no longer need to explicitly note who originally discovered them. Common knowledge includes information that most people know, or information that is widely known and accepted within your audience. Below are three wisely used tests for common knowledge:

- Quantity: Can I find this fact in 3-5 independent sources? (Or 5-7 if your sources are web-based)

- Ubiquity: Is this fact acknowledged across disciplines, or it is held to be true only by a specific group, organization, profession, or academic discipline?

- Generality: Can I find this fact listed without attribution in one or more general reference sources? General reference sources include dictionaries, encyclopedias, atlases, and almanacs. For some purposes and some audiences, Wikipedia could be considered a general reference source.

17.1.3 Conceptualization

This occurs when a writer borrows a concept from another source. Sometimes it is easy to remember where the concept came from, in which case it should be formally remembered in the form of a citation, but other times the origin might be murky. When that happens, it is still okay to make use of the concept without attribution, as long as you remember that the goal is always to give credit wherever credit is due and whenever it is possible.

17.1.4 Summarizing

Summary is part of the trinity of remembrance, along with paraphrasing and quoting. Summary is a process of distillation, or filtering out the unnecessary to express a more complex idea in the simplest terms, so it is a movement from something bigger to something smaller:

Summarize when you want to:

- Provide context

- Provide background

- Simplify a complex text

- Get quickly to the main point

In a summary, make sure to:

- Use plain language

- Be objective

- Avoid analysis

- Avoid interpretation

- Don’t include opinion

Remember that summary distills information, so you are working to filter the the information and condense it to about 20% of the size of the original.

Summarizing and paraphrasing are both best accomplished by following the process below, with the goal of summary being to condense and distill the information, and the goal of paraphrase being to retain and reword the information.

17.1.4.1 Put it in

For summarizing, read the text to be summarized for understanding. You may need to read it several times:

- Read it straight through the first time without pausing to make notes

- Read it through a second time. Look up any words you don’t know the meaning of. Take notes about any ideas or associations you make while reading it. Highlight the concepts or ideas that seem the most important. Cross out the parts that seem unnecessary. Jot down any additional ideas that occur to you as you are reading it.

- Read it through a third time. Use any research tools at hand to further explore the points you find to be the most interesting. Wikipedia works well for this purpose.

17.1.4.1.1 Levels of Reading Comprehension

Consider these four levels of reading comprehension – the goal is to get to the fourth level before even making an attempt at summarizing the text:

17.1.4.1.1.1 Conjectural

The reader has not read the text, but is able to make intelligent guesses about the content based on the title, things other people have said about it, what they know about the author, or other contextual clues.

17.1.4.1.1.2 Literal

The reader understands the facts, data, and the definitions of the words. She understands what the text says, literally, but may not understand some of the subtle connotative meaning that is established through internal context; internal relationships between concepts, ideas, and characters; the use of tone, and the use of rhetorical or literary devices like metaphor, simile, and sarcasm.

17.1.4.1.1.3 Inferential

The reader is able to infer meaning by paying attention to the subtle connotative meaning that is established through internal context; internal relationships between concepts, ideas, and characters; the use of tone, and the use of rhetorical or literary devices like metaphor, simile, and sarcasm.

17.1.4.1.1.4 Evaluative

The reader understands the broad implications of the text and is able to situate it in the context of the conversation or discourse community it belongs to. By comparing it to other texts and authors, she understands whether it is a departure from the main current of thought, a reiteration, or an outright opposition.

Take the following passage, for example:

The Indian tribes of North and South America do not contain all the blood groups that are found in populations elsewhere. A fascinating glimpse into their ancestry is opened by this unexpected biological quirk. For the blood groups are inherited in such a way that, over a whole population, they provide some genetic record of the past. The total absence of blood group A from a population implies, with virtual certainty, that there was no blood group A in its ancestry; and similarly with blood group B. And this is in fact the state of affairs in America”[1]

A list summary could be created for this passage without moving beyond a literal understanding of it:

While this summary does condense some of the information, it doesn’t necessarily pull out a main thread, or the one thing that makes it interesting and useful for your purposes. For that reason, it doesn’t really suggest anything interesting to the reader either. Once you yourself have come to a fourth level, or evaluative understanding of it, the main point begins to crystallize. If you understand, for example, how this information fits into theories of how the continent of North America was first populated, you understand how this information is situated, and how it informs or relates to, say, the land bridge theory or to Native American mythology. To be clear, this is not information that you will include in your summary (save it later for synthesis), but it does help keep focus focus on the most important elements.

Knowing the implications of the author’s words, that the absence of other blood groups in Indian tribes on the North American continent to some extent refutes the short chronology land bridge theory might prompt a different focus for the summary:

This short summary doesn’t yet go into the implications. It remains objective. It doesn’t mention any counterarguments or alternative viewpoints. It offers no opinions. All that can be saved for a response or synthesis. What it does do is pull out a main thread that can later be responded to or placed in conversation with other texts.

17.1.4.2 Put it Down

This is the most important step: don’t look at the original text while you write your summary, otherwise you will end up with a list summary – just a list of things the author said – which will bore your audience. So the idea is to put the original source down or minimize it on your computer screen now that you have put the information in your head.

17.1.4.3 Spin it Around

Spin the information around in your head for a minute and let it interact with all the other stuff that is in there, including your existing knowledge on the subject, your familiarity with other texts, and even your own beliefs, values, and opinions. Yes, you want to remain objective, but colliding with and being weighed against your own pre-existing knowledge and opinion is what will give your factual summary its unique character. Let it simmer. Let it marinate. Then, before your mind wanders too far, move to the next step.

17.1.4.4 Write it Down

Without peeking at your source, write your summary straight from your head. Even if you aren’t sure about a point, keep writing, just like you would if you were freewriting.

17.1.4.1.5 Pick it up

Turn the original text over or maximize the window on your screen so you can now compare your summary and the original side by side.

17.1.4.1.6 Check it Out

Make sure your summary aligns in fact and spirit with the original. Now is the time to make sure your own opinion didn’t color your summary too much or blind you to important pieces of information. Here you can make some slight modifications, but if you did the reading thoroughly, the chances are you got the summary right too.

17.1.4.1.6 The “Feynman Technique”

The Feynman technique is similar to the above technique, but…

1. Study

2. Explain in the simplest terms.

3. Revisit the elements you can not explain in simple terms. Reread. Fill in the gaps.

4. Write the summary in the simplest and most concise terms possible.

17.1.5 Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is saying what someone else said originally in your own words. Typically you use about the same number of words in your paraphrase as were in the original, so it is a 1:1 relationship, and a parallel movement. Parallel, in that the words used to express the singular meanings are just slightly different.

Use paraphrasing when you want to:

- Say it better

- Simplify it

- Clarify it

- Maintain your own voice

- Assert your own authority

In a paraphrase make sure to

- Use your own words

- Use your own sentence structure

- Refrain from adding anything extra

The same process described under the summary section also works best for paraphrase…

- Put it in

- Put it down

- Spin it around

- Write it down

- Pick it up

- Check it out

…with the most important part being to put the original down while you rephrase. If you don’t, you will likely to end up with patchwriting, which is the practice of just plugging words into someone else’s phrasal pattern.

17.1.6 Patchwriting

Patchwriting is the practice of strategically replacing words or phrases in a quote without altering the underlying sentence structure or word order. It is a practice to be avoided in most writing, especially if you want to claim the words as your own. Consider the following two sentences. The first is a quote from Abe Simpson, and the second is a rendition of the same quote using patchwriting:

- “The important thing was that I had an onion on my belt which was the style at the time. They didn’t have white onions because of the war. The only thing you could get was those big yellow ones.”

- The significant item was that I had an onion on my sash which was the fashion of the day. They didn’t have colorless onions because of the armed incursion. The only item you could obtain was those large yellow ones.

- It is tempting to use this word replacement strategy when paraphrasing, but what you end up with is not really a paraphrase at all – it is a Frankenstein-like monster instead.

17.1.6.1 Avoiding Patchwriting

To avoid patchwriting:

- 1) Read the text to be paraphrased for understanding.

- 2) Put the original text face down on the desk or close the window on your device.

- 3) Wait 30 seconds for it to percolate in your head.

- 4) Write down what it said in your own words.

17.1.7 Para-quoting

Including a quote from a research source in an academic paper is like inviting a friend to a family dinner. While you may know them well, the rest of your family may not, so if your friend just barges in  through the door without first being introduced, they might seem rude and obnoxious. Some people call these kinds of unintroduced guest sentences “floating quotes” because they really don’t have a reference or anchor that ties them to your work, and they seem like they just kind of floated in from somewhere. Other people call them dropped quotes because they seem like they just dropped in out of nowhere. But is there a kinder, gentler way to get a quote into your essay? A way that is less disruptive, but that still makes it seem like it belongs? One technique for accomplishing this is called paraquoting.

through the door without first being introduced, they might seem rude and obnoxious. Some people call these kinds of unintroduced guest sentences “floating quotes” because they really don’t have a reference or anchor that ties them to your work, and they seem like they just kind of floated in from somewhere. Other people call them dropped quotes because they seem like they just dropped in out of nowhere. But is there a kinder, gentler way to get a quote into your essay? A way that is less disruptive, but that still makes it seem like it belongs? One technique for accomplishing this is called paraquoting.

If you want to para quote, start by putting some quotation marks around the quote. You don’t want that great quote you found to look like it just got out of bed and dropped in without even getting dressed first.

Be polite and introduce the quote. Find an appropriate signal phrase or signal verb. In this case, “Yoda says” may be the simplest and most appropriate. Put a comma in front of the quote unless you are using the word that to introduce it or otherwise integrating it into your sentence.

Is it done? Well, not really. The quote has been introduced, but only by name. The audience has no idea where it came from, where it works, where it lives, or what it wants to be when it grows up. They have yet to learn all that stuff that parents want to know when you bring a quote home for dinner. Let’s assume it came from an imaginary book written by Yoda called “There is Only Try.” In the works cited page, your entry would look like this:

If you don’t use the author’s name in the in-text citation, you’ll need to put the author’s last name, followed by the page number. Remember, you don’t need a comma between the name and the page number. And since Yoda doesn’t have a last name, just use his first name as his last name. Don’t forget to move the period after the parenthetical citation. If you do use the author’s name in the signal phrase, or if you haven’t cited another author since the last time you cited the first one in the section, you only need to put the page number in the in-text citation.

Remember, the quote is only there to support the author’s points, not to take over the whole conversation. That would be rude. When integrating a quote like this into a sentence of your own, MLA Format allows you to decapitalize the first letter in order for the newly formed sentence to fit together seamlessly.

Framing, finally, tells the reader exactly why you are using the quote and how it relates to your essay. Framing requires a more detailed introduction before the signal phrase, and a short explanation after the quote, like this:

Now this quote seems happily integrated into the conversation. Using this technique of para-quoting, citing, and framing not only improves the flow of a paper, but it also boosts the credibility of the author by keeping his or her voice primary.

17.1.8 Quoting

At the far end of the spectrum of remembering is direct quoting. Generally, it is better to quote directly only when absolutely necessary. Quoting has a 1:1 relationship from the original to the quote. That is to say, what is in between the quotation marks should match up with the quote exactly, with a few minor exceptions.

Use direct quoting when you want to:

- Preserve the integrity of the original

- Borrow authority from the original (see borrowed ethos)

- Highlight the style and word choice of the original and can’t say it any better yourself

- Closely analyze or explicate the original.

When quoting, make sure to

- Frame the quote with an introductory sentence that explains where the quote is coming from and explains why you are using it and with a followup sentence that clarifies, restates, or otherwise comments on it.

- Use a signal phrase, with or without the name of the author, to introduce the quote rather than just dropping it as a complete sentence.

- Enclose all directly quoted material in quotation marks

- Use an in text citation to cite the quote and refer the reader to a corresponding source in the Works Cited or References page.

- Integrate the quote into your sentence, using either a signal phrase, a paraquote, or a combination of both.

- Replicate the quote word-for-word, unless you want to leave out some words or slightly change the form of any of the words. If you leave words out, represent that with ellipses to replace the missing words. If you need to change the form of the word in order to integrate the quote into your own sentence, enclose the modified word in brackets.

17.1.8.1 Signal Phrases

A signal phrase is usually the name of an author + a verb. It might be something like

Simpson acknowledges that “hitting rock bottom is not what it always was.”

As Simpson acknowledges, “hitting rock bottom is not what it always was.”

In both of these sentences, the portion highlighted in yellow is the signal phrase, the most important components of which are the name of the author and the signal verb. You can find a fairly comprehensive list of signal verbs below. As you can see, the signal verb can cast a number of different lights on the quote that follows it, so choosing the right verb can make all the difference. Try replacing “acknowledges” in the above examples with a different signal verb from the list below to see what different rhetorical effects can be achieved by something as simple as changing the signal verb.

17.1.8.2 Signal Verbs

| accepts | accounts for | acknowledges | addresses | adds |

| admits | advises | affirms | agrees | alleges |

| allows | analyzes | announces | answers | argues |

| ascertains | asks | asserts | assesses | assumes |

| believes | categorizes | cautions | challenges | charges |

| cites | claims | clarifies | classifies | comments |

| compares | complains | concedes | concludes | concurs |

| condemns | confesses | confirms | confronts | confuses |

| considers | contends | continues | contradicts | contrasts |

| convinces | counters | criticizes | critiques | deals |

| decides | declares | deduces | defends | defines |

| defines | delineates | demands | demonstrates | denies |

| describes | determines | develops | diminishes | disagrees |

| discovers | discusses | disproves | disputes | disregards |

| distinguishes | editorializes | emphasizes | endorses | ends |

| envisions | establishes | evaluates | exaggerates | examines |

| exemplifies | experiences | experiments | explains | explores |

| exposes | expounds | expresses | facilitates | feels |

| finds | finds | formulates | furnishes | grants |

| guides | highlights | hints | hypothesizes | identifies |

| illuminates | illustrates | implies | indicates | infers |

| informs | initiates | inquires | insinuates | insists |

| interprets | intimates | introduces | investigates | iterates |

| lists | maintains | makes the case | marshals | measures |

| mentions | negates | notes | notices | nullifies |

| objects | observes | offers | opposes | out |

| outlines | perceives | persists | persuades | phrases |

| pictures | pleads | points | points out | portrays |

| posits | postulates | praises | presents | proclaims |

| professes | pronounces | proposes | propounds | protects |

| proves | provides | purports | qualifies | questions |

| ratifies | rationalizes | reaffirms | realizes | reasons |

| reconciles | reconsiders | refers to | refines | refutes |

| regards | reiterates | rejects | relates | relinquishes |

| remarks | reminds | replies | reports | repudiates |

| resolves | responds | restates | retorts | reveals |

| reviews | says | sees | shares | shifts |

| shows | specifies | speculates | states | stipulates |

| stresses | submits | substantiates | substitutes | suggests |

| summarizes | supplements | supports | supposes | surveys |

| synthesizes | tells | tests | theorizes | thinks |

| traces | uncovers | urges | uses | utilizes |

| verifies | verifies | views | wants | warns |

| with | writes |

17.1.9 Synthesizing

One well-known example of synthesis is the process of combining two molecules of hydrogen and one molecule of oxygen to create two molecules of water. Put the molecules together, add a spark, and abracadabra – you have water! In the simplest terms, synthesis is creating something new from existing pieces. The synthesized thing is so new and different that it bears little resemblance to any of its parts. We know how to do this with water, but how do we do it with texts?

17.1.9.1 Dialectical/Dialogical Thinking

The best essays require the author to utilize dialectical and dialogical thinking to put texts into conversation with one another. [2]

17.1.9.1.1 Dialectical Thinking

According to the Foundation for Critical Thinking , dialectical thinking is:

Thinking within more than one perspective…to test the strengths and weaknesses of opposing points of view. (Court trials and debates are, in a sense, dialectical.) When thinking dialectically, reasoners pit two or more opposing points of view in competition with each other, developing each by providing support, raising objections, countering those objections, raising further objections, and so on. Dialectical thinking or discussion can be conducted…by conceding points that don’t stand up to critique, trying to integrate or incorporate strong points found in other views, and using critical insight to develop a fuller and more accurate view.[3]

While the term dialectic has evolved somewhat since Aristotle used it, the idea is still roughly the same. In Hegelian dialectics a thesis provokes an opposing thesis, or antithesis, and the resulting tension between the two ideas eventually leads to a synthesis of them, incorporating perhaps their best and most salient features in the new creation. This synthesis then becomes a new thesis, which provokes a new antithesis, and this evolutionary process begins again. The idea is that the synthesis is more than the sum of the thesis and the antithesis, but something new altogether that continues to evolve. Dialectic thinking, then, is thinking that is driven by conflict between opposing ideas. It is beneficial to think dialectically, then, when considering the opposing viewpoints you are likely to encounter when researching any topic. Welcoming opposing or alternative viewpoints and playing them against each other can effectively generate new ideas and forward thinking.

17.1.9.1.2 Dialogical Thinking

According to the Foundation for Critical Thinking opens in new window, dialogical thinking is:

Thinking that involves a dialogue or extended exchange between [multiple] points of view or frames of reference. Students learn best in dialogical situations, in circumstances in which they continually express their views to others and try to fit other’s views into their own.[4]

More often than not there exist more than two competing voices in the “conversation” surrounding an area of interest to you. Additionally, not all of the voices in a particular conversation are diametrically opposed to one another. Some of them may agree with one another in ways that differ in their fundamental approach, some of them may disagree with one another in theory, but not in practice, some may like the author of an idea but dislike the idea, some may disagree, but not care that much, while others may agree, and care a lot. The fact that there are so many more relationships among ideas than symmetrical opposition is what prompted the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bahktin to suggest that the idea of “many voices,” or dialogical thinking might be more inclusive way of thinking about texts (See The Dialogic Imagination).

17.1.9.1.3 Putting Texts into Conversation with One Another

Unfortunately, while dialectic thinking and dialogic thinking are very similar, one can’t be neatly subsumed in the other. While among the many relationships and voices in the larger conversation (dialogical) you might discover a neatly opposing relationship that could generate a synthesis, once that has happened that particular dialectical relationship breaks free and becomes its own thing, often uninfluenced by the multiple voices surrounding it. Consider the two ways of thinking as closely related, but necessarily separate.

To put sources or texts in conversation with one another dialectically, use the contrasting method. Imagine the two texts as if they were two different people who could be put in a room together to “hash it out.” What would the texts, if they were people, say to each other? This imagined conversation, which you can relate in your writing through inference, summary, and paraphrase, can help you discover a resolution that would involve some concessions on both sides. However, don’t limit yourself to finding only concessions. Here is a chance to think of original solutions that re-imagine the shared problem in creative ways. That re-imagining is where true synthesis happens.

Imagine, for example, that Text A and Text B both want to cross a river. Text A wants to cross the river by using poles to anchor them against the current, and Text B wants to cross the river by throwing a rope across the river and balancing on it. Text B says the current is too strong, that the pole would break, and they would be washed away. Text A says that neither one of them can balance well enough to cross the river by walking a tightrope. Through their argument it is possible for them to come up with the idea to either use the pole as a balancing device to cross by foot on the tightrope or use the rope to anchor them to a tree while using the pole as additional support. Or they might arrive at true synthesis and find that by climbing the tree and anchoring the rope to it, they can see far enough to spot a footbridge around the bend. Note that they would have to climb the tree in either solution, and the argument itself proved to contain the elements necessary for an inventive resolution.

Conversely, to put sources in conversation with one another dialogically, imagine a roomful of people talking about different aspects of the topic, from different points of view, utilizing different current and historical frames of reference. Some of them are speaking loudly, some of them softly; some of them have a large circle of conversationalists, while others have smaller circles of people.

In terms of the previous example, imagine several other travelers showed up, and all wanted to cross the river. Maybe one of them shows up with a cartload of tree branches, suggesting they use the tree branches as flotation devices. Then someone gets the idea to lash the tree branches together to make a raft, and another person gets the idea to use the pole to navigate the depths of the water while they cross the river on the raft. Dialogic thinking affords synthesis through incorporation of many parts to create a solution.

You can use quotations sparingly to recreate such a conversation in your writing. To successfully create the conversation, however, you will have to rely heavily on your own words to distill the complex ongoing conversation for the reader.

17.1.9.1.4 Questions

The questions below for dialectical thinking are in Writing Arguments by John Ramage et. al. The questions for dialogical thinking are adapted from the same questions.

17.1.9.1.4.1 Questions to Promote Dialectical Thinking

- What would writer A say to Writer B?

- After I read writer A, I thought______; however, after I read writer B, my thinking had changed in the following ways:_______.

- To what extent do writer A and writer b disagree about facts and interpretations of facts?

- To what extent do writer A and writer B disagree about underlying beliefs, assumptions, and values?

- Can I find any areas of agreement, including shared values and beliefs, between writer A and writer B.

- What new, significant questions do these texts raise for me?

- After I have wrestled with the ideas in these two texts, what are my current views on the issue?

17.1.9.1.4.4 Questions to Promote Dialogical Thinking

- What would writer A say to Writer B? How would writer C complicate that conversation?

- After I read writer A and B, I thought______; however, after I read writer C, my thinking had changed in the following ways:_______.

- To what extent do the writers engaged in this conversation disagree about facts and interpretations of facts?

- To what extent do do the writers engaged in this conversation disagree about underlying beliefs, assumptions, and values? Are there any groupings evident in this regard?

- Can I find any areas of agreement, including shared values and beliefs, between the writers engaged in this conversation? Are there any groupings evident in this regard?

- What new, significant questions do these texts raise for me?

- After I have wrestled with the multiple ideas in these texts, what are my current views on the issue?

17.2 Elaboration

After all is said and done, nothing is actually said and done. Once you have narrowed your focus to a particular conversation, listened to that conversation as much as you can, systematically To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven: A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted; a time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up; a time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance; a time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing; a time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away; a time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak. Ecclesiastes 3: 1-7forgotten everything but the best parts of that conversation, and formally recognized and remembered those parts in writing, then it is time to elaborate on them and/or respond to them. Elaboration is very much a kind of invention, but its starting point is a particular source, a set of sources, or a particular point made by any of those sources.

Use elaboration to:

- Answer questions

- Solve problems

- Pose solutions

- Make predictions

- Identify implications

- Extrapolate: Infer the unknown from the known

- Add meaning

- Provide examples

17.3 Common Ground/Opposing Arguments

17.3.1 Common Ground

If you are writing a Rogerian or Invitational argument, you will be devoting a lot of time and space to common ground. Even if you are following the classical or CARS organizational scheme, common ground must be acknowledged either implicity or explicitly. The warrant in the Toulmin argument is constituted by common ground you share with the audience, and going back to the Audience Analysis section in “The Audience” can help you find beliefs, values, and opinions you share with the audience.

17.3.1.2 Opposing Arguments

Yet another component of memory includes identifying and addressing opposing arguments. Failure to do so can single-handedly bring down an argument, just like a lack of defense can lose a championship game. Once you have identified an opposing argument, you will want to begin by summarizing it.

17.3.1.2.1 Summarizing

One of the first steps to handling an opposing argument is to summarize it fairly. Sometimes it is tempting to cast the opposing argument in a poor light, but in the end that has the potential to work against you by casting a doubt on your fair-mindedness. Using plain language to describe the opposing argument briefly makes you appear willing to consider the argument, so when you refute it you appear that much more credible.

17.3.1.2.2 Refuting

Writing Arguments offers the following 6 ways you can refute an opposing argument or alternative point of view:

- Cite counterexamples and counter testimony

- Cast doubt on the representativeness of sufficiency of the examples

- Cast doubt on the relevance or recency of the examples, statistics, or testimony

- Question the credibility of an authority

- Question the accuracy or context of quotations

- Question the way statistical data were produced or interpreted.[5]

Items 1, 2, and 6 clearly concern logos, 3 concerns kairos, and 4 and 5 concern ethos. Number 2 is very specifically related to the “Hasty Generalization” fallacy. You can also return to Rhetorical Source Analysis, in “Memory: Intertextuality II” and use the questions there to refute arguments.

17.4 Reducing Dependency on Sources

Depending on your purpose, you may need more or fewer sources. Ideally, you will incorporate mostly summary and paraphrase to recall your sources, while using direct quotes only when there is a very good reason to do so. The rule of thumb is that no more than 20% of an academic essay should be quoted material. If your school uses Turnitin or Vericite, then you will see an originality score that shows how much non-original material your essay contains, and that should be less than 20% even with the Works Cited or References pages.

Other free online originality checkers include:

17.4.1 Use Summary, Paraphrase, and Para-quoting

Rumi is sitting by a fountain in a small square in Konya reading to students from his father’s dazzling spiritual diary, the Maarif. Shams breaks through the group and throws the invaluable text, along with other books on the pool’s edge, into the water. ‘Who are you and what are you doing?’ asks Rumi.”It is time for you to live what you’ve been reading,’ replies Shams.If you see that you have a high percentage of directly quoted material, use summary, paraphrase, and para-quoting to reduce your dependency on quoted material. Keep in mind that the sources are only there to support your original argument. Summary, paraphrase, and para-quoting are often intertwined with one another. When you intersperse summary, paraphrasing, and para-quoting you can create meaningful rhythms in an essay.

17.4.2 Start Without Sources

One method to ensure you don’t become too dependent on your sources is to write your first draft without sources at all. This is a large scale implementation of the same technique advocated for summary and paraphrase. Once you have immersed yourself in the research, set it all aside to begin writing your first draft. When you have the first draft, you can add them back in as necessary to support your own argument.

Not really proceeding from its reputed origin, source, or author; not genuine or authentic; forged (OED)