15

Finding Sources and Listening to what they Say

15.1 Overview of Memory

Not everything Cicero had in mind when he elevated memory to the five rhetorical canons is relevant in a world where an entire library of information can fit in the palm of your hand. On the other hand, much of what they considered memory can, with very slight modification, be applied to this modern world we live in. For our very practical purposes, the most important components of memory include intertextuality, proofreading, revision, and reflection.

In the following three chapters, you can find information about three important types of intertextuality, including 1) listening, 2) forgetting, and 3) remembering.

15.2 Research and Writing as a Conversation

In addition to proofreading and revision, the rhetorical canon of memory includes a capacity to recall the other participants in a conversation and the points they have brought up. Some of you might remember Ten-Second Tom from the movie 50 First Dates, who had a memory disorder resulting from a traumatic head injury (as did the main character) that allowed him to remember only about ten seconds of a conversation, at which point he would sort of reset, without any understanding of the conversation he was involved in ten seconds earlier. As the ancient Greeks conceived of it, memory was not only the ability to memorize a speech, but also an ability to recall the most important parts of an ongoing conversation about the topic they were speaking on. When applied to writing, you must imagine a lengthy and ongoing conversation taking place over centuries and across national borders. When you[GU1] sit down to write a paper, you are effectively joining a conversation that has been going on for an awfully long time, so you must take care to recall the major elements, as Aristotle might have remembered what Plato said a few days ago in regard to truth and sophism. To join a conversation without a nod to the most important contributions to the topic is to put one’s ignorance on display and is ultimately rhetorically ineffective.

One of the reasons to conduct thorough research before writing an argumentative research essay is to avoid such a display. By the time you get ready to contribute to the conversation you are joining (And you are inevitably joining a conversation whenever you put pen to paper, or fingers to the keyboard) you should, by conducting objective research, have a fairly good idea of what has already been said about the topic. In this endeavor, it is important to identify multiple perspectives, otherwise your understanding of the conversation might be similar to your understanding of a telephone conversation we only hear one side of. Worst of all, if we make it to our final argumentative research essay and forget to address opposing arguments, your arguments will fall as flat as a straw house in a hurricane once anyone brings up any points you fail to mention.

Intertextuality has to do with all those notecards that a speaker with a good memory can set aside. It concerns the ability to successfully join an existing conversation, as all writing and speaking requires. That is, very rarely are you the first person to mention anything about a topic, and thus it is particularly important to engage with what has already been said. A paper or project like an argumentative research essay does not exist in a vacuum. It is both a response to and an entry into an already existing conversation, and if it is original and thought-provoking, it will likely be responded to as other people join the conversation. Intertextuality is simply the ability to include the important points that have already been made, identify how they inform one’s topic, and document their sources. Think of the library and the internet as extensions of your own memory, in the same way that a car or bicycle is the extension of your legs. It is important that these sources be relevant and credible, and the more they are, the more they contribute to your own credibility, or ethos.

15.3 Actual Conversation

Actual conversation is really just a genre of communication, most commonly referred to as face-to-face conversation. While telephone calls, ZOOM calls, and Facetime sessions count, they really aren’t a substitute for the nonverbal and context clues that some researchers suggest make up seventy percent of face-to-face communication. In other words, if you aren’t right there, you are only really getting about thirty percent of the conversation.

15.3.1 Informal Conversations

If researching and writing an essay is like a conversation, then doesn’t it seem like the best researchers and writers should also be the best conversationalists? That sounds right, but it just isn’t always true. Any writing teacher can tell you that sometimes the most able conversationalists in a class struggle to transfer all that eloquence to the written page, while the back row introvert turns out to be the life of the party.

If you aren’t a conversationalist, no worries. There is no one-size-fits-all formula to being a great conversationalist, but like writing, practice always makes you better. And like writing, with practice we all develop our own style as we go. Here is one formula that distills a thousand pages of skimming books and Googling on the topic:

15.3.1.1 Ask questions

If you aren’t curious about what your conversation partner or partners have to say, it is hard to fake it. To ask genuine questions, you have to have curiosity. If you don’t have it, you can cultivate it, and because it is such a fundamental part of human nature, you will probably like it.

15.3.1.2 Listen

Some of us are really good at this part, to the point that it is the main thing we do in a conversation. We tend to attract our opposite: those who are just as good at talking as we are at listening. This explains why, for introverts, who are usually really good listeners, conversation can be exhausting.

15.3.1.3 Talk

Unless you are one of the rare extreme talkers who seem to love nothing more than the sound of your own voice, it can also be exhausting to be involved in a conversation with an extreme listener. Most people, though, fall somewhere between the two extremes, and even then, they may be more or less talkative in different rhetorical situations.

15.3.1.4 Ernate

Take turns. Taking turns is an art that can only be learned from practice with all sorts of different types of conversationalists and conversations. Subtle cues like lowering the pitch at the end of a sentence, a slight pause, or direct eye contact can indicate a talker is ready to switch roles and become the listener. What makes this even more difficult is that the types of cues differ between cultures and dialects. The good news is that even though psychologists and communication experts have all tried to encode these cues, you already know how to do it intrinsically. The real experts are those of us who learned to take turns talking the same way we learned to walk down a crowded hallway without bumping into each other. It all comes down to practicing and paying attention.

15.3.2 The Socratic Seminar

- A Socratic seminar is a more formal kind of conversation, often taking place inside a college classroom,but that doesn’t at all mean that it should be stuffy and academic. Socratic seminars can take all kinds of forms, but the most important rules include:

- The leader of the seminar can only ask questions. They can not answer questions or make statements, even to clarify the question.

- The participants need to take orderly turns answering the questions, but they can also add questions of their own. (Use of a talking stick or raising of hands can facilitate this in a formal way if organic turn-taking mechanisms have broken down)

- Yes or no answers are not allowed.

- Participants should take every opportunity to ask for clarification and build upon answers provided by other participants.

15.3.2.1 Socratic Questions

The Socratic seminar begins with Socratic questions. What are Socratic questions? you might ask. A Socratic question, named after Socrates, whose conversational skills never really went beyond asking questions, should:

- Be open-ended questions, with no yes/no answers allowed

- Invite responses that grow from the thoughts of others

- Invite responses that continually ask for clarification

- Foster a communal spirit of inquiry

15.3.12.1.1 Types of Socratic Questions

According to Richard Paul, the Socratic questions fall into the following categories. Note that many of the examples in the table below are taken directly from the topoi questions in the chapter “Invention: Advanced Techniques.” The topoi questions are nearly all Socratic in nature, aside from How does the dictionary define x?

| Type of Question | Example |

| Clarification |

|

| Assumptions |

|

| Reasons and Evidence |

|

| Alternative Perspectives |

|

| Implications/Effects |

|

| Questioning the Question |

|

The possibilities for questions are endless. You can either use questions from this list or use them as a template to create your own. Just remember that the main feature of the Socratic question is that it has no “correct” answer.

15.4 Listening in to the Bigger Conversation

Unlike an actual conversation, listening to the whole conversation doesn’t have to be done at Denny’s or in a classroom. It can be done in your own home with a computer or other device, or in the library. In this larger conversation you will be listening to books, reading scholarly articles, perusing newspaper articles, finding web pages, evaluating studies, discovering government reports, and looking at other sources information like those described in section 15.5 “Who Can I Ask? (Types of Sources),” but you will still need to start with questions.

15.4.1 Research Questions

Closely related to the Socratic question is the research question. With the formulation of a research question, you begin to listen in a more targeted way to everything that has been said and is currently being said in the conversation you are hoping to join. You might feel like you are heading back to the house of invention at this point , and in a way you are. Even though now you have decided on a general topic, you are still trying to figure out what has already been said in this great conversation so you know exactly what you can say that hasn’t already been said.

And what is good, Phædrus, And what is not good…Need we ask anyone to tell us these things? -Socrates

With your research question, you are trying to figure out what to read. If you aren’t sure what your question is, you might do some general reading without a specific question in mind. This kind of reading is both invention and memory and is like a child of a split household who spends part of his time at the House of Invention and part of his time at the House of Memory. Once you figure out your research question, you will need to do some focused inquiry in order to answer it. After you have determined your thesis, your reading is likely to be even more focused on sources that can be used to support your reasons and refute alternative arguments. That is not to say you won’t still be answering questions, but these questions will be limited to the kinds of questions that come up while making the argument. For example, if you find yourself arguing that Kent Brockman is trying to create a health scare with a headline like “Due to the Krusty Burger Virus Springfield General Hospital is already at 99% Capacity,” you might need to do some additional reading to answer the question “How unusual is it for Springfield General to be at 99% capacity?” The point is, real world argument writing requires the reader to alternate between asking questions and making claims, and therefore between reading and writing.

15.4.1.2 Qualities of Research Questions

Research questions should be focused, researchable, feasible, specific, complex, value-free, and relevant.

15.4.1.2.1 Focused

A research question should be focused on a narrow topic. This just means that it is important to have already applied some of the techniques of invention listed in “Invention: Basic Techniques” and “Invention: Advanced Techniques” to arrive at a topic less general than, for instance, the meaning of life or how big space is.

15.4.1.2.2 Researchable

A research question should be answerable with research obtained from primary and secondary sources. However, don’t despair if you don’t find a single source that handily answers your research question. You might have to pretend to be Sherlock Holmes and piece clues together to answer the question. That isn’t a problem, it just indicates you have a research question that few people have attempted to answer. That is a good thing in terms of originality. If you can answer it, you have found an opening in the conversation, and a possible space for a new argument. If, after some patient research, you deem the question unanswerable, you can adjust the scope of the question to something easier to answer.

15.4.1.2.3 Feasible

You may be able to answer your research question, but not be able to do it in the time you have allotted. If this is the case, you may have to modify your question accordingly.

15.4.1.2.2.4 Specific

If you have already narrowed the umbrella topic your research question falls under, it should be fairly easy to make the question more specific.

The questions What is the meaning of life? or How far does space go? Are probably too general. More specific questions might include What does the Western Branch of American Reform Presbylutheranism teach about the meaning of life?, or What are the chances of a manned mission to Mars occurring in the next twenty years?

15.4.1.2.2.5 Complex

While you need a specific question, it should still be complex enough to be interesting, engaging, and valuable to the audience you will be addressing. You want a question that, when answered, does not provoke a “duh.” It should not be a yes/no question.

15.4.1.2.2.6 Value-Free

For the most part, you will want to avoid value judgements in your research questions because they will reduce your angle of vision. The angle of vision is narrow if it is only looking for a particular answer that you have either consciously or unconsciously predetermined. You want instead to build in an open-mindedness, or a wide angle of vision, into your research question so you don’t ignore research, knowledge, or arguments that disagree with some preconceived notion. In other words, make sure you are starting with the question and not the answer. Genuine curiosity is central here. Words that can alert you to a value-based question are should, better, worse, etc.

15.4.1.2.2.7 Relevant

The question should be relevant to the topic you have chosen. If you are writing about cats, your central question probably shouldn’t be about dogs.

15.4.1.2.2.8 Exception: The Paired Research Question/Thesis Statement

Now, to contradict everything that has been said above, if you plan on writing a quality argument or a proposal argument, some sources suggest that you should use the word should in your research question even though using it transforms it into a yes/no question with value implications. The benefit of using the word should in your research question is that once the research is in, you can change it into a thesis statement simply by moving the word should. For example:

Research Question: Should the Springfield Sanitation Commissioner institute 24-hour curbside garbage pick-up.

Thesis: The Springfield Sanitation Commissioner should institute 24-hour curbside garbage pick-up.

15.5 Who Can I Ask? (Types of Sources)

Writing makes it possible for conversations to be preserved for years, and for that reason the mountain of what has already been said continues to grow. Digital storage capabilities make possible massive archives of information that allow great portions of that mountain of previous conversation instantaneously accessible.

How can you make the information manageable when faced with this huge mountain of what has already been said? One thing you can do is look for the best parts of what has already been said, because there is a lot of that mountain that’s just landfill. There’s a little bit of mountain on top of a whole lot of trash (To some, this might sound suspiciously like the internet!) Once you have decided on a research question, or a set of research questions, the next step is to find the answers. One strategy when looking for answers is to start with the general and follow the trail to the more specific.

15.5.1 Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

Of the general types of sources described below, most can also be categorized along the lines of originality or proximity to some original material. Primary sources include sources that were created in close conjunction with an actual event or that were an event in themselves, like a speech or novel. Secondary sources comment on, analyze, or interpret primary sources. Tertiary sources index, catalog, compile, or summarize primary and secondary sources.

15.5.1.1 Primary Sources

- reports

- poems

- novels

- speeches

- photographs

- original manuscripts

- journals

- letters

- diaries

- scrapbooks

- eyewitness accounts

- marginal notes in books

- artifacts

- audio recordings

- video recordings

- films

- some documentaries

- historical newspaper accounts

- business records

- original art

- architecture

15.5.1.2 Secondary Sources

- textbooks

- histories

- biographies

- literary criticism

- film criticism

- art criticism

- book reviews

- political commentaries

- biblical commentaries

15.5.1.3 Tertiary Sources

- almanacs

- encyclopedias

- bibliographies

- manuals

- handbooks

- indexes

Note that these categories are not set in stone. For instance, if you are using a manual for a John Deere tractor from 1967 to talk about the history of agriculture, then it is being used as a primary source.

15.5.2 Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Qualitative data consists primarily of words, while quantitative data consists primarily of numbers. A field observation, ethnography, or interview will probably contain mostly qualitative data, while a survey or experiment will probably contain mostly quantitative data. Both types of data are important to support a strong argument.

The spreadsheet below is an example of quantitative data. The data records the responses of 21 students in an Advanced English Composition Class when asked to rate whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement: College athletes should get paid a salary just like professional athletes do. Column A represents their opinion one day before they either participated or observed a reasoned debate on the topic. Column B represents their opinion after discussing the issue only with people who agree with them, and Column C represents their opinion immediately after participating in or observing the debate. Currently, the table is sorted from top to bottom from those who strongly supported the claim to those who strongly opposed it (column A).

If you analyze it closely, you will see that the numbers tell a story, and can be used to confirm or deny claims or hypotheses. This interpretation of statistical data is an important skill to employ when using it to support your argument. Here is one way of interpreting this data:

Consider these claims:

Claim 1: Discussing an issue only with people who agree with you will result in your preexisting opinion becoming even stronger, and thus more polarized due to confirmation bias.

Quantitative Analysis:

Now look at the data, and decide whether it supports or proves this claim. After looking closely, you will see that out of the participants who initially indicated the supported the claim (Joe, Margaret, Jamie, Marylin, Bob, Wilma, Monica, Phoebe, Fred, and Karson), 3 became more convinced after discussing it with only participants who agreed with them (Bob, Phoebe, and Fred), while 3 actually became slightly less convinced (Joe, Monica, and Karson). Out of the participants who initially indicated they disagreed with the claim (Joey, Mack, John, Bonnie, Susie, Donald, Mindy, Jane, Trinity, Lila, and Maria), only 2 (Mack and Bonnie), became more convinced of their initial stance, while 1 became slightly less convinced of their original stance and moved closer to the middle, and another (Donald) switched sides completely.

In terms of individual participants moving towards polarization or toward consensus after the discussion with others who agreed with them, this data is rather inconclusive. Here are the percentages:

24% became more polarized after discussing an issue with only people who agreed with them.

24% became less polarized after discussing an issue with only people who agreed with them.

52% didn’t change their minds at all after discussing an issue with only people who agreed with them.

Maybe considering the data in terms of degree, or how far each participant moved on the scale away from their initial stance, would provide more conclusive results. In other words, while most participants only moved 1 point on the scale of 1 to 10 in any particular direction, a few of them moved a lot of points on the scale in a particular direction, and the extent of that movement might reveal something significant. Here are the percentages:

Overall, after participating in discussions with only people who agreed with them, participants became 55% less convinced of their initial stance in terms of degree, compared to 45% more convinced.

This data is a little bit more conclusive, and seems to cast some doubt on Claim 1. However, since this sample size only includes 21 college students, it can’t yet be generalized to a larger and more diverse population. If we extrapolated this to a larger sample, then maybe there is an identifiable trend that warrants further exploration with larger and more diverse sample sizes.

Qualitative Analysis

But that isn’t the whole story. More can be learned by collecting qualitative data, perhaps in the form of interviews with each participant about why they changed their mind. In the course of interviewing the participants, perhaps we discovered that Donald and Trinity did not like each other, and that they disagreed on almost every other point, which caused Donald to switch sides immediately when he saw Trinity had similar opinions. This is an example of cognitive dissonance, or the discomfort people feel when holding two incompatible ideas. Since it was psychologically uncomfortable for Donald to both dislike Trinity and hold the same opinion as her, he resolved the cognitive dissonance by changing his opinion.

Does this new qualitative evidence invalidate the quantitative evidence? Can both Donald’s and Trinity’s reported opinion changes be thrown out as aberrations? Not really. Any good qualitative study will take into account other factors, including instances where the respondent was just confused and marked the wrong choice. In this example, the researcher can learn that their might be a confounding variable that she didn’t consider – the relative ethos of the participants of the discussion. That is, if an individual finds that they don’t like the people who they agree with, they might change their mind.

Claim 2: A reasoned debate will bring the two opposing sides closer to consensus on a topic.

Quantitative Analysis

Aristotle believed that the goal of deliberative rhetoric was ultimately consensus, so that if he was right, the above claim should be supported by evidence. Is it? The same interpretive techniques can be applied to the same data to see if it does indeed support this claim.

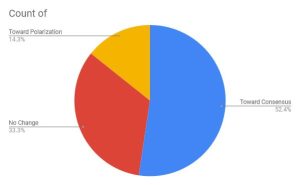

The numbers are much more conclusive in this instance, as 60% of the participants actually changed their minds one way or the other post-debate. Of these, 25% became more polarized in their opinion after the debate, while 75% became less polarized, or more toward the middle. For all participants, 33.3% didn’t change their minds at all, 14.3% became more polarized, and 52.4% moved toward consensus. This data, represented in a pie chart, would look like this:

This seems to support Aristotle’s best hopes for deliberative rhetoric, but again, the sample size is small and not representative. To generalize these results to the population at large would be an example of the logical fallacy of hasty generalization.

Qualitative Analysis

The experience of the researcher has been that these numbers are less consistent across debates, and that debates that turn emotional seem to actually have the opposite effect. A pack mentality sometimes takes hold when enough students are highly invested in the claim, and results in much higher rates of polarization. In this debate, interviews with the participants suggested that the biggest factor in their change was that”both sides had good points,” and that both sides appeared willing to consider the opposing points of view presented to them in a fair and deliberative manner.

15.5.3 Triangulation

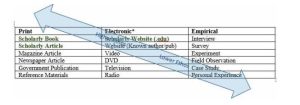

To keep your research balanced you should use a variety of different types of sources, including electronic, print, and empirical sources. See the table below for types of sources that can be used and their relative value in terms of providing ethos to you as an author and your argument paper:

15.5.3.1 Print Sources

15.5.3.1.1 Scholarly Books

Scholarly books can be found in libraries, on library websites, through Google scholar, and through Google books. Here is some evidence that a book is scholarly:

- The author’s credentials show they are a scholar and an expert in their field.

- The publisher is a scholarly publisher or university press. Some examples include Oxford University Press, Duke University Press, and University of New Mexico Press.

- The text contains in-text citations that refer the reader to a source contained in a references or works cited section, footnotes, or endnotes.

- The book includes a bibliography that contains known scholarly sources.

15.5.3.1.1.2 Scholarly Articles

Scholarly Articles can be found in databases provided by your library, on Google Scholar, on the internet, and at the library in bound volumes.

- The author’s credentials show they are a scholar and an expert in their field.

- The publisher is a peer-reviewed, scholarly journal. Examples include Cultural Anthropology, International Economic Review, and Theoretical Linguistics.

- If you are searching a research database on your library’s website, the database will likely have a way to limit any search to peer-reviewed articles only.

- Academic Search Premier

- Some useful general research databases include:

- Academic Search Premier

- JSTOR

- Project Muse

- Proquest Research Library

- Web of Science

- The text contains in-text citations that refer the reader to a source contained in a references or works cited section, footnotes, or endnotes.

15.5.3.1.3 Magazine Articles

Popular magazine articles can be found on the internet, in bound volumes in libraries, and in databases provided through your campus or local library.

Some popular newspaper and magazine databases include

- Academic Search Premier

- Proquest Current Newspapers

- MasterFile Premier

- CQ Researcher

- Infotrac Newsstand

15.5.3.1.4 Newspaper Articles

Newspaper articles can be found on the internet, in library archives, and in databases provided through your campus or local library.

- Reader’s Guide Retrospective (Good for finding historical articles from 1890-1982. This is a good source for locating primary source materials.)

- CQ Researcher

- Google News

Of course, if you are looking for information related to a particular geographical area, then the website for that news paper or libraries close to that area are the best sources.

15.5.3.1.5 Government Publications

Government publications are a rich source of information on a diverse range of topics. These often go ignored, just because they are not the first place a researcher thinks of going unless their topic is related to some specific government operation, like the U.S. Forest Service for information on forest fires.

A few places you can go to find government publications include:

- Catalog of U.S. Government Publications (https://catalog.gpo.gov/F?RN=231207942)

- FDSys (https://www.govinfo.gov/). Here you can find presidential executive orders, congressional bills, etc.

- Campus or local library

- The website for a specific government agency

15.5.3.2 Electronic Sources

15.5.3.2.1 Scholarly Website

Scholarly websites can be a highly credible source of information. Look for the same information you would be looking for in scholarly books and articles plus a .edu extension. Places to find scholarly websites include

- Google Scholar

- Google (Using the advanced search settings at https://www.google.com/advanced_search, choose .edu websites only.)

15.5.3.2.2 Website (with known author, publisher)

Just because a website is not scholarly doesn’t mean it can’t be used as a source for a scholarly paper. It is good to have a mix of popular and scholarly sources, so as long as your research is grounded in scholarly research, you can certainly include other sources without harming your ethos.

15.5.3.2.3 Video

Video is a great source of information. Even popular movies or television shows can be used to inform your topic. You can find video resources in the following places:

- YouTube

- Ted Talks

- Netflix

- Cable Subscriptions

- Amazon Prime Video

- Hulu

15.5.3.2.4 Radio

By using the radio, you can conduct research while driving or riding your bike! You just have to remember what you were listening to so you can document or locate it later. Most public radio stations and community radio stations keep audio archives and transcripts so accessing those later is easy. Others don’t, so you might have to find the website of the program if it is syndicated. Otherwise, so you might have to create an audio note on your digital audio recorder or ask Siri to send an email or text message to reference later.

15.5.3.3 Empirical Sources

Empirical sources are sources that rely on direct observation or experience.For that reason, they are most often considered a primary source. Empirical sources can either be original, meaning you, as the writer, collected the information, or they can be referenced by you. Original empirical sources used in combination with referenced empirical sources can ground your argument in the real world. This kind of information is what Aristotle refers to as inartistic proof – it is evidence that already exists, it just needs to be uncovered, revealed, or cited by the researcher.

15.5.3.3.1 Interview

An interview provides primarily qualitative data. If you are interested in conducting an interview, the steps are listed below.

15.5.3.3.1.1 Request the Interview

- Identify an expert, witness, or other participant in the area you plan to research.

- Request an interview as soon as possible so that you can offer the interviewee flexibility in terms of dates and times.

- In your request, introduce yourself and the purpose of the interview.

- Provide an estimate of how long you think the interview will take.

15.5.3.3.1.2 Prepare for the Interview

- Watch or listen to skilled interviewers (talk show hosts, journalists).

- Research the field or discipline the interviewee works in.

- Research the work of the interviewee.

- Research the area of your inquiry so you can 1) appear prepared, 2) couch your questions in terms of the discourse community the interviewee belongs to, and 3) ask intelligent and productive questions.

15.5.3.3.1.3 Create Questions

- Start with the research question or questions you developed in section 14.4.1 “Research Questions.”

- Questions should be organized in some sequence that makes sense, with a clear beginning, middle, and end.

- Group questions like you would paragraphs so you don’t end up meandering from topic to topic.

- Avoid closed questions unless they are necessary to clarify something.

- Avoid leading questions, or questions that push your own agenda.

- Create possible follow-up or contingency questions for each question. A follow-up question asks for more details, additional information, or further elaboration; a contingency question is a follow-up question that depends on the answer to a previous question i.e., if the interviewee answers Question A favorably, I will ask her X; if she answers it unfavorably, I will ask her Y.

15.5.3.3.1.4 During the Interview

- Be sure to exchange the usual pleasantries at the beginning of the conversation; identify common interests (the topic at hand is probably one of them!)

- The interview should be a conversation, not an interrogation.

- Don’t be afraid of silences. Allow the interviewee time to compose their answers. Sometimes, remaining silent after their answer can encourage further elaboration.

- Avoid interrupting the interviewee.

- Before ending, ask the interviewee if they have anything more to add.

- Be sure to thank the interviewee for their time and indicate how their answers will be valuable for your work. If you really want to present yourself as a professional, send a note of thanks for the interviewee’s time.

15.5.3.3.2 Survey

A survey can provide the creator with both qualitative and quantitative data.

15.5.3.3.2.1 Writing Survey Questionnaire Items

Types of Items

Questionnaire items can be either open-ended or closed-ended.

Open Ended Questions. Simply ask a question and allow participants to answer in whatever way they choose. The following are examples of open-ended questionnaire items.

- “What is the most important thing to teach children to prepare them for life?”

- “Please describe a time when you were discriminated against because of your age.”

- “Is there anything else you would like to tell us about?”

Open-ended items are useful when researchers do not know how participants might respond or want to avoid influencing their responses. It is best to use open-ended questions when the answer is unsure and for quantities which can easily be converted to categories later in the analysis.

Closed-Ended Questions. Closed-ended items are used when researchers have a good idea of the different responses that participants might make. They are also used when researchers are interested in a well-defined variable or construct such as participants’ level of agreement with some statement, perceptions of risk, or frequency of a particular behavior. Closed-ended items are more difficult to write because they must include an appropriate set of response options. However, they are relatively quick and easy for participants to complete. They are also much easier for researchers to analyze because the responses can be easily converted to numbers and entered into a spreadsheet. For these reasons, closed-ended items are much more common.

All closed-ended items include a set of response options from which a participant must choose. For categorical variables like sex, race, or political party preference, the categories are usually listed and participants choose the one (or ones) that they belong to.

Types of closed end questions include multiple choice, true/false, yes/no.

15.5.3.3.2.2 Writing Effective Items

A rough guideline for writing questionnaire items is provided by the BRUSO model (Peterson, 2000)[9]. BRUSO stands for “brief,” “relevant,” “unambiguous,” “specific,” and “objective.”

Be Brief. Effective questionnaire items are brief and to the point. They avoid long, overly technical, or unnecessary words. This brevity makes them easier for respondents to understand and faster for them to complete.

Be Relevant. Effective questionnaire items are also relevant to the research question. If a respondent’s sexual orientation, marital status, or income is not relevant, then items on them should probably not be included. Again, this makes the questionnaire faster to complete, but it also avoids annoying respondents with what they will rightly perceive as irrelevant or even “nosy” questions.

Be Unambiguous. Effective questionnaire items are also unambiguous; they can be interpreted in only one way. For instance, if you were to ask the question “How many alcoholic drinks do you consume on a typical day” different respondents might have different ideas about what constitutes “an alcoholic drink” or “a typical day.”

Be Specific. Effective questionnaire items are also specific, so that it is clear to respondents what their response should be about and clear to researchers what it is about. A common problem here is closed-ended items that are “double barrelled.” They ask about two conceptually separate issues but allow only one response. For example, “Please rate the extent to which you have been feeling anxious and depressed.” This item should probably be split into two separate items—one about anxiety and one about depression.

Be Objective. Finally, effective questionnaire items are objective in the sense that they do not reveal the researcher’s own opinions or lead participants to answer in a particular way. Table 9.2 shows some examples of poor and effective questionnaire items based on the BRUSO criteria. The best way to know how people interpret the wording of the question is to conduct pre-tests and ask a few people to explain how they interpreted the question.

| Criterion | Poor | Effective |

|---|---|---|

| B—Brief | “Are you now or have you ever been the possessor of a firearm?” | “Have you ever owned a gun?” |

| R—Relevant | “What is your sexual orientation?” | Do not include this item unless it is clearly relevant to the research. |

| U—Unambiguous | “Are you a gun person?” | “Do you currently own a gun?” |

| S—Specific | “How much have you read about the new gun control measure and sales tax?” | “How much have you read about the new sales tax?” |

| O—Objective | “How much do you support the new gun control measure?” | “What is your view of the new gun control measure?” |

15.5.3.3.2.3 Formatting the Questionnaire

The introduction should be followed by the substantive questionnaire items. But first, it is important to present clear instructions for completing the questionnaire, including examples of how to use any unusual response scales. Remember that the introduction is the point at which respondents are usually most interested and least fatigued, so it is good practice to start with the most important items for purposes of the research and proceed to less important items. Items should also be grouped by topic or by type. For example, items using the same rating scale (e.g., a 5-point agreement scale) should be grouped together if possible to make things faster and easier for respondents. Demographic items are often presented last because they are least interesting to participants but also easy to answer in the event respondents have become tired or bored. Of course, any survey should end with an expression of appreciation to the respondent.

15.5.3.3.3 Experiment

An experiment uses the scientific method to find real world cause and effect relationships. If you start with observation, here is how it goes:

15.5.3.3.3.1 Observation/Research Question

An experiment is designed around a question that arises from observation. For instance, let’s say you noticed that your plants seemed to grow better in the room where you listened to classical music, your research question might be:

15.5.3.3.3.2 Hypothesis

Your hypothesis functions almost like a thesis in that it can be formed directly from the question. It is important that it be falsifiable, or in other words, able to be proven or disproven. A suitable preliminary hypothesis for the classical music theory might be:

Note that once you identify the independent and dependent variables, this hypothesis will become more specific.

15.5.3.3.3.3 Independent Variables

The independent variable is the variable you suppose is the cause of something. In this case it is:

15.5.3.3.3.4 Dependent Variables

The Dependent Variable is the effect or effects you suppose might be the effect caused by the independent variable. In the proposed plant experiment, it is:

15.5.3.3.3.5 Confounding Variable

A confounding variable is a variable that is correlated somehow to one of the independent variables that could also explain the effect. In the proposed plant study, a confounding variable could be noise. Perhaps plants grow better when any noise is present, as opposed to when no noise is present.

15.5.3.3.3.6 Operational Definitions

In a well-designed experiment, the variables must be very specifically defined. These definitions are called operational because they aren’t the dictionary definitions but rather the definitions you will be operating under within the confines of the experiment.

Classical Music is defined as symphonic renditions of works by the core canon of classical composers, including Bach, Chopin, Schubert, Mozart, Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, Shuman, Liszt, and Grieg.

Plant Growth is defined as measurable height.

Other dependent variables might include weight, spread, and vibrancy of color. The important feature of the dependent variable is that it is measurable.

Noise is defined as any sustained sound disturbance above sixty decibels.

15.5.3.3.3.7 Experimental Groups

An experimental group is any group upon which a treatment is applied. A treatment is the application of the independent variable. In the proposed plant experiment, the main treatment would be classical music played at sixty decibels.

In order to filter out the possible confounding variable of noise, you could introduce another possible independent variable and treatment that includes Death Metal music played at the same volume as the classical music.

You would then have two experimental groups: Group A, which receives the treatment of classical music played at 60 decibels continuously for six weeks, and Group B, which receives the treatment of Death Metal music played at 60 decibels continuously for six weeks.

15.5.3.3.3.8 Control Group

A control group is a group that receives no treatment at all. In the proposed plant experiment, this group of plants would sit in a quiet room with no music at all played for six weeks.

15.5.3.3.3.9 Random Selection

The subject of your experiment are people, plants, petri dishes, etc. They should be similar in all respects across all experimental and control groups. For the proposed plant experiment, the ideal subjects would be a hundred seeds chosen at random from a larger pool of subjects.

15.5.3.3.3.10 Results/Conclusions

In the results, the hypothesis is either confirmed or denied. You, as the experimenter, determine what measurement is required for the hypothesis to be confirmed. For instance, if the average height of the plants exposed to classical music is >1cm after six weeks than both Experimental Group B and the control group, then the hypothesis is confirmed and your question is answered.

15.5.3.3.4 Field Observation

15.5.3.3.5 Case Study

A case study is a detailed and focused study of a particular subject. That subject can be a person, group, place, event, or phenomenon. Follow the steps below to conduct a case study:

- Identify a representative case.

- Articulate a theoretical framework.

- Observe and collect information.

- Describe the case in objective terms

- Analyze the case using the theoretical framework you identified in step 2.

Case studies are useful for looking at a particular subject in depth. Their limitation is that they are not as generalizable to a larger population in the same way that a survey or experiment with a random sample might be.

15.5.3.3.6 Personal Experience

Note that even though table 15.5.3 makes it look like empirical evidence, especially personal experience, is never useful, it really depends on the rhetorical situation. If the author is an expert on the topic, obviously their personal experience is going to be highly credible. Also, some English instructors might encourage you to include personal experience in order to make a more personal connection with the audience. In cases where it is presented in conjunction with highly credible, scholarly sources, personal experience can be very powerful and persuasive.

15.5.3.3.6.1 Point of View

If you do use a personal anecdote, you don’t have to cite it. You signal you are relating a personal experience by switching to the “I” point of view. Once you do, the strategies of the personal narrative apply:

15.5.3.3.6.2 Setting

Use vivid language and concrete details. Include references to all five senses, including sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell.

15.5.3.3.6.3 Character

In most personal experience, there are other people involved. Make them real, with recognizable personality traits.

15.5.3.3.6.4 Dialogue

Include some real dialogue if you can.

15.5.3.3.6.5 Plot

Think of buildup, climax, and resolution.

15.5.3.3.6.6 Conflict

A story without conflict is hardly interesting. In your short rendition of a personal experience, some element of conflict and resolution should be incorporated.

15.5.3.3.6.7 Theme

This, of course, should relate somehow to a point you are making in your essay.

15.6 Documentation

It is important to document what you see and hear along the way, for every conversation and for every experience, because our memories, as a result of the invention of writing, and just as Plato feared, are not what they used to be. Once we learned how to write lists of things to remember, we lost some of our natural ability to file important items in our head. Even now, you may not even know your best friend’s phone number because your phone does it for you.

We can’t really go back and un-invent writing, but now that it is here, we can use it to our advantage. And although methodical note-taking seems intrusive – like it gets in the way of actual experience – it can prove invaluable later on as we attempt to reconstruct what we heard and where we heard it from. It is worth noting that Jane Goodall, who recently “blamed a ‘hectic work schedule’ and her ‘chaotic method of notetaking'”[1] for plagiarized sections of a revised edition of her book, Seeds of Hope. She took a lot of notes, but she had no system for recalling where they came from.

15.5.1 Note Cards

Here is one old-school way of keeping track of notes: 3×5 Index Cards. It is bulky, but effective. It also helps some people feel more grounded to have a physical location for each idea, and can help create an environment for spatial memory to thrive. The following are some basic guidelines, but as you do more research, you may develop your own system.

15.6.1.1 Source Cards

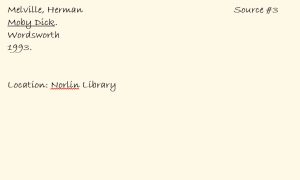

It is a good idea to create a source card for each source you use. You can then assign a number or symbol to that card, so that you can quickly refer to it on each individual note card. If you have multiple ideas or quotations from a single source, this saves you from having to write the source information on each card.

If you are using MLA format, the source card should include all nine elements of the MLA container system, if they are available, including author, title of source, title of container, other contributors, version, number, publisher, publication date, and location.

Here is an example source card, with the linked note card appearing later.

15.6.1.2 Note Cards

Rule #1: Each note card should contain only one idea or quote!

Rule # 2: Any other rules are guidelines, really, so you can modify them as you please. But never, ever break the first rule!

Here is how it works:

- Some researchers use note cards for their preliminary research, while others use them in conjunction with an outline. If you are in the preliminary research stage, write down a description or tag for the idea, fact, or quote in the upper left-hand corner of the card. If you are using the note card in conjunction with an outline, use the corresponding outline heading to indicate where the card belongs in the essay you have planned.

- In the upper right-hand corner, write down the number or symbol of the source card that has the information for the source of the idea, fact, or quote.

- In the body of the card, write down a paraphrase of the idea, the fact, or quote that you want to use. Make sure to put quotation marks around any directly quoted material!

- In the bottom right hand corner, write down the page number where the idea, fact, or quotation is located. If no page number, try a paragraph number or other description that will help you or reader locate it later. If it is a video or audio recording, write down the time stamp in hours:minutes:seconds.

- If you do this a lot and have multiple projects, consider writing a code word for the project the card belongs to in all caps in the bottom left-hand corner.

- Modify as necessary, but once you have committed to a scheme, don’t change midstream. That will just confuse you.

Some free online note card applications exist, the most notable of which is SuperNotecard at https://www.supernotecard.com.

15.6.2 Notebooks

15.6.2.1 Note-Taking Systems

Each of the following methods have advantages and disadvantages, as some are more appropriate in certain situations, while others are more appropriate in other situations. Each one uses a chronological, hierarchical, or spatial scheme for organizing your notes. Some are better for capturing information quickly, and others are better for organizing information so you can find it later. Some are better for taking lecture notes, some are better for taking conversation or interview notes, while others are better for taking reading notes. Carlos Castaneda, who his known for his ethnographic research (now known to be largely fiction) of the Yaqui Indians, claimed to have developed a note-taking system using a short pencil or pen and a pad of paper that never left his pocket in order to take notes surreptitiously while in sensitive situations where the speakers might not take kindly to his note-taking activity. Call it the Castaneda System, if you like, and see if you can develop the skill of writing legible notes in your pocket.

15.6.2.1.1 Cornell Method

- Use a rule to draw a vertical line in your notebook about two inches from the left side of the paper, leaving a wider space on the right side. Create a space at the bottom of about two inches, where you will summarize or synthesize the information above.

- On the left side, include short cues to help you remember the more detailed information you will include in the larger right column. This is often called the recall column.

- On the right side, include more detailed information, including ideas, facts, or quotations, author names, and page numbers. This is often called the notes column.

- When finished with a lecture, interview, or section of a book, use the space at the bottom of each page to summarize everything on the page. This is often called the summary area.

This method works well for lectures, conversations, or interviews, when you aren’t aware of the organization of the material beforehand. It organizes primarily by chronology.

15.6.2.1.2 Outlining Method

- Use standard outline headings to organize your notes as you read or listen to an well-organized lecture. (I, A, 1, a, i, or 1.,1.1,1.1.1, etc.)

- Remember the outlining rule No A without a B? That doesn’t always apply here because you are trying to sort out the outline as you go, and your lecturer or author might take an unexpected turn.

- Keep track of page numbers or timestamps in parentheses at the end of each line. One way of keeping track of where you are on a page is to use page numbers with decimal points to indicate how far down on the page the note you are referring takes place, so if it is halfway down on page 34, you might write (34.5) at the end, so you know exactly where to look if you need to find the original material again.

This method works well for taking notes on written materials. It organizes the information by hierarchy. Chapters, headings, and subheadings can transfer directly over to your notes. If headings or subheadings don’t exist, you can usually figure out where things go. Each paragraph likely has a hierarchical structure.

15.6.2.1.3 Sentence Method

- Write down thoughts, ideas, quotations, facts, dates as they are presented to you.

- Number each one sequentially or by time. Numbering them sequentially is faster because you don’t have to look at a watch or clock each time you make a note.

- Keep track of page numbers or time stamps in parentheses at the end of each line. One way of keeping track of where you are on a page is to use page numbers with decimal points to indicate how far down on the page the note you are referring takes place, so if it is halfway down on page 34, you might write (34.5) at the end, so you know exactly where to look if you need to find the original material again.

This method is pretty basic, and therefore applicable to multiple note-taking situations. It might be slightly better for reading and listening to lectures, since it takes some thought to compose each sentence. This note-taking strategy uses chronology to organize notes.

15.6.2.1.4 Word Mapping Method

- Draw a bubble or square at the center of your notebook page.

- Write the author, event, or topic in the bubble or square at the center of your notebook page.

- Create additional bubbles or squares, writing keywords or phrases inside them, and connect them in ways that seem meaningful or seem to represent the connections the author, lecturer, or interviewee seems to be making.

- Keep track of page numbers or time stamps in each bubble or square, whenever possible.

This method is really just a visual outline. It is a variation of the brainstorming method described in the Invention chapter, only now you are using it to map someone else’s mind and not your own. This note-taking strategy used spatial and hierarchical reasoning to organize notes.

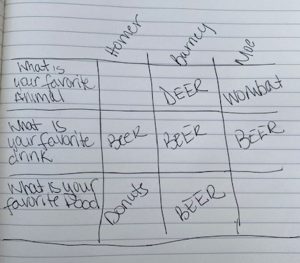

15.6.2.1.5 Charting Method

- Create a chart or table with columns on a sheet of notebook paper.

- Once you have created the chart, there are many different ways to organize it. If it is a book, then it could be organized by chapters horizontally, across the top, and then subjects that cut across chapters arranged vertically. If you plan on interviewing multiple people then you can put the people horizontally across the top, and then questions vertically, so one square in the matrix is Groundskeeper Willie’s answer to Question 2, while another square represents Side Show Bob’s answer to the same question.

The chart method of note-taking would be good for taking notes on a live conversation or interview. It takes some creativity to determine the values of the horizontal and vertical axes, but once you have done that, the relationships among the squares in the matrix might shed new light on the information. It is also rather easy to fill out quickly, so it has the advantage of being both easy to put information into and easy to interpret the information at a glance.

15.6.3 Digital Notebooks

Most of the above methods can be used with digital notebooks. Evernote and Microsoft OneNote both have options for stylus entry, so that the user can either type information in or input drawings and handwriting with a stylus. Text-to-speech is available with both, which makes entering information fairly easy in the right circumstances.

Just remember, batteries still run low much more often than ink pens run out of ink.

15.6.4 Digital Audio Recorders

Digital Audio Recorders are ideal for recording interviews or important conversations, but they can also be used to take reading notes or capture ideas you have while driving down the road. You can use a speech-to-text converter like Dragon, or use one of the many available automated transcription services to transcribe your audio notes into text entries. This method is easy to input, but a little more difficult to catalog an access. It is easy to get hours and hours of recordings that never make it to the written notebook if you aren’t diligent at transcribing.

Licenses

The section, “!@# Survey” is a derivative of “Constructing Survey Questionnaires” in Research Methods in Psychology – 2nd Canadian Edition by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, used under CC BY. “!@# Survey” is licensed under CC BY by Ty Cronkhite.

The section “!@# Field Observation” is a derivative of “Field Research: What it is?” in Research Methods for the Social Sciences: An Introduction by Valerie Sheppard and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, used under CC BY. “!@# Field Observation” is licensed under CC BY by Ty Cronkhite.

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/apr/01/jane-goodall-seeds-of-hope-plagiarism ↵

A made up word to complete the acronym: AskListenTalkERNATE. It just means to take turns asking questions, listening, and talking.

To infer the unknown from the known by identifying a trend in the data.

A deviation or departure from what is normal, usual, or expected, typically an unwelcome one. Also as a mass noun: deviation, abnormality, departure from the norm (OED).