3

1.1 Understanding Audience

If you have seen a commercial for Mountain Dew, Budweiser, or Tostitos recently, don’t think that the copywriters don’t know exactly who you are. While you may think that anyone who watches these commercials is the audience, the highly paid writers and marketers don’t make that mistake. They have a target audience that consists of people they think are most likely to buy the product, and every second of every commercial is tailored specifically to that audience Unless you are 18-24, male, Caucasian, earn less than $20k per year, have little to no college education, have one or more kids, and buy the product primarily at Dollar stores or convenience stores in the afternoon, then you are not part of that target audience. You may be hearing the writers, but they really aren’t talking to you.

Not only do the writers of Mountain Dew advertisements know the demographics of their audience, but they also know a tremendous amount about the psychographics of their audience, or their beliefs, attitudes, opinions, and behaviors. They figure this out in numerous ways, including direct observation, surveys, interviews, focus groups, Google search term monitoring, and social media monitoring. Marketers and advertisers also have a good idea of how to analyze their audience in terms of the purpose and occasion, which is sometimes called a situational analysis. The goal is to have their audience reach out and buy Mountain Dew, so the best genre and message is going to reach potential consumers where and when they are the most thirsty: mid-afternoon, on the road, in front of  the television, snapchat, www.mensjournal.com, and www.snowboarder.com. Knowing where the audience is, what they are doing, and what media they are using is essential to Mountain Dew’s advertising campaign. This audience-savvy approach has proved to be extremely effective, otherwise they wouldn’t be spending millions of dollars a year on it.

the television, snapchat, www.mensjournal.com, and www.snowboarder.com. Knowing where the audience is, what they are doing, and what media they are using is essential to Mountain Dew’s advertising campaign. This audience-savvy approach has proved to be extremely effective, otherwise they wouldn’t be spending millions of dollars a year on it.

The question is, when writers say their audience is all Americans, people in general, or anyone who reads my paper, how can they possibly know what might be compelling or persuasive to that audience? Budweiser puts trucks in their advertisements because they know their audience likes trucks. Mountain Dew shows people jumping off cliffs because they know their audience likes extreme sports. A life insurance company shows two young mothers at a playground with their two-year old children, and one of them says “It is so brave of you to leave all your family with your debt when you die.” Guess what – all three of these tropes have proven highly effective for particular audiences, but a Ford truck doesn’t belong in a life insurance commercial any more than a worried mother belongs in a Mountain Dew commercial watching twenty-year old men jumping off cliffs. The point is, an essay addressed to all Americans, people in general, or anyone who reads my paper is doomed from the start because it cannot avoid the inclusion of conflicting arguments. Arguments that work well for one group can serve exactly the opposite purpose for another. Jumping off cliffs seems fun to some, dangerous to others. Arguing that your product or idea is safe will fall flat if you address it to an audience that just wants to have fun, since it is common knowledge that something can’t be safe and fun at the same time. A failure to understand their audience would have copywriters writing a script that has a worried mother driving up in a Ford truck with a life jacket in her hand, insisting that the cliff diver put it on before he jumps. Nobody is going to go out and buy a Mountain Dew after seeing that.

1.2 Understanding Discourse Communities

Before going on to think about a particular audience, it is important to consider the concept of discourse communities, since it is likely that you and your audience belong to the same discourse community, and equally likely that your general purposes align to some degree. That is to say that the rhetorical situation, including the writer, purpose, and audience, is already defined by a community of interested stakeholders.

According to John Swales, a discourse community has these characteristics:

- A discourse community has a broadly agreed upon set of common public goals.

- A discourse community has mechanisms of intercommunication among its members.

- A discourse community uses its participatory mechanisms primarily to provide information and feedback.

- A discourse community utilizes and hence possesses one or more genres in the communicative furtherance of its aims.

- In addition to owning genres, a discourse community has acquired some specific lexis.

- A discourse community has a threshold level of members with a suitable degree of relevant content.[1]

Some examples of discourse communities include the following:

- Nurses

- Prison Guards

- A Sorority

- Republicans

- Firefighters

- Parents

Discourse communities can be nested within other discourse communities or overlap with others. Think about those discourse communities listed above. Nurses could be an umbrella discourse community over emergency room nurses, with nurses in the Springfield General Hospital emergency room being still another sub-community. At the same time, any of these nurses might belong to the larger community of parents, fathers, and fathers of children in 5th grade at Springfield Elementary.

1.3 Understanding your Audience

The audience you are addressing is a thread that runs through every aspect of rhetoric. Every rhetorical choice you make while writing your essay, from invention to delivery, is driven primarily by your choice of audience. Understanding who your audience is in terms of beliefs, attitudes, opinions, and behavior, in conjunction with understanding your purpose, will help you make the most effective choices regarding purpose, genre, arrangement, style, reasons, memory, delivery, and use of persuasive appeals.

1.3.1 Purpose

Sometimes the purpose determines the selection of your audience, and sometimes the selection of your audience determines the purpose. If in the Invention phase you consciously considered topics that are relevant to a discourse community you belong to, then your claim is more likely to be appropriate or of concern to that audience. If you discovered a claim by thinking first about what things interest you, there is still a good chance it is also of concern to a discourse community you belong to. In either case, as you refine your claim and tailor it to a specific audience, you may have to use qualification to make it more likely to be accepted.

1.3.2 Genre

Your purpose and audience will determine your genre and your medium. The first examples of genre that come to mind are literary and film genres, like horror, comedy, or fantasy. If these are the first examples you think of, you aren’t wrong, but genre can be much more than that. Genre has not only to do with the purpose and the audience, but also the chosen medium. Take the Mountain Dew case as an example. If their purpose is to sell Mountain Dew to Snowboarders on their way to or from Vail, the obvious genre and medium is a billboard near a convenience store, especially since Mountain Dew is purchased mostly at convenience stores. If your audience is the Congress of the United States of America, the genre might be a letter to your congress person proposing a piece of legislation, with the medium being either an email or a sheet of paper in an envelope. Genre and medium are codependent, so the medium can very much determine the rules for the genre. In the case of the letter to Congress, the constraints, limitations, and capabilities of each dictate slightly different formatting conventions, while the wording and general style remain the same. It could be argued that other differences between the letter and the email are becoming more distinct, such as the formality of each. It seems an email with one or two typos is acceptable, while a typed letter is considered more formal and has to be exact.

Some examples of genres include:

| memos | business letters | street signs | billboards | parking tickets |

| wills | job applications | resumes | text message | bumper stickers |

| personal essays | academic essays | blog entries | news stories | family newsletters |

| song lyrics | limericks | t-shirts | class notes | lab reports |

| pool rules | classified advertisements | cartoons | instructions | posters |

If you are in an advanced research or composition class, your genre might be predetermined for you, and is likely to be the academic essay. This limits your audience to some extent, as you wouldn’t really be writing an academic essay to, say, the “Dew Culture,” but you still have quite a bit a room to customize your message for a particular group.

1.3.3 Arrangement

If an audience is highly resistant, you might want to use a Rogerian, invitational, or delayed-thesis model of arrangement. If they are undecided or only slightly resistant, the more aggressive classical model, with the thesis up front, might be more effective. If they already agree with you, then you might want to question why you are making the argument in the first place.

1.3.4 Style

The audience you are addressing should determine the style that you use, especially in terms of grammatical and lexical usage. In her essay “Mother Tongue,” Amy Tan suggests that we all use several different Englishes in the course of a day or week, depending on who we are talking with. Whether you realize it or not, you adjust your language to fit the needs of the occasion and the audience on an almost minute-by-minute basis. For example, you may be in class one minute asking a question like “How do you imagine the ascendance of Capitalism affect the linguistic practices in Early Modern England?” and then the next minute sending a text to your friend that says “idk – maybe ladder – in class right now – board! LOL” Later you might use other “englishes” when you buy a Mountain Dew from a convenience store clerk, tell your mother about your day, or tell your teammates how well they are playing.

Writing an argumentative research essay requires a more formal tone, usually achieved by employing Standard American English, avoiding contractions, avoiding second person, avoiding slang, avoiding idiomatic expressions, avoiding shortened words or abbreviations, and always referring to the authors of your sources by last name. Even with these expectations, you still have a lot of wiggle room to adjust your language to the conventions of the discourse community you are addressing. Also, to some extent the genre dictates the style, even for identical audiences.

1.3.5 Reasons

Reasons are highly sensitive to audience beliefs, values, opinions, attitudes, prejudices, biases, fears, and behaviors. Reasons that work for one audience won’t work for another, so it is singly important to have an idea of who your audience is before settling on the reasons you want to include in your argument.

1.3.5.1 Beliefs

Although beliefs can be based on facts, they can also be based on faith, moral principles, cultural beliefs, gut feelings, or even dreams. By definition, beliefs are subjective. The primary difference between a belief and an opinion is that a belief is inarguable , while an opinion is arguable or up for debate.

1.3.5.2 Values

Values are strong beliefs about what it good, desirable, and worthy. Because they are strong beliefs, they are more likely to influence one’s behavior. Examples of values include the following:

- Honesty

- Safety

- Financial Security

- Family

- Loyalty

- Happiness

- Human Life

- Relaxation

- Leisure

- Enjoyment

- Exercise

- Health

Values often come in conflict with each other, as honesty and loyalty, financial security and relaxation, or safety and enjoyment often do. So too, values can change as they are tested by experience.

1.3.5.3 Opinions

Opinions, unlike beliefs, are always more or less based on experience, fact, or empirical understanding. When someone says, “that’s just my opinion,” they don’t mean it isn’t factually based. They mean it is debatable, arguable, or that you are free to disagree. Opinions can usually be tested with the I think test: I think that, therefore it is an opinion. Some examples opinion include the following:

- Too much sugar is bad for your health.

- Krusty’s Burgers taste good.

- It should not be against the law to wear seat belts.

- The legal drinking age is too high.

- Being trendy isn’t as cool as being right.

- The Griddle Driven coffee at Skip’s diner is a lot better than the regular.

- Buzz Cola tastes good.

- It is not fair for North Haverbrook to hoard all the water.

- The Springfield Glen Golf Club is too pretentious to belong in Springfield.

- The wealthiest one percent don’t need to have as much money as they do.

- Absolute power corrupts absolutely.

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

Many of the aphorisms in Appendix A could be either opinions or beliefs.

1.3.5.4 Attitudes

Attitudes are unstated opinions that may manifest themselves in other behaviors. People aren’t always aware of their attitudes or where their attitudes they originated. They consist of likes, dislikes, affinities, aversions, trusts, and distrusts.

1.3.5.5 Prejudices

Prejudices are like attitudes in that they involve assumptions about someone or something that are not based on experience or reason. A prejudice is a form of the hasty generalization fallacy, since it often involves making a generalization about a class of ideas, things, or people based upon very limited experience. If you assume when you meet a skateboarder that he is rude based only on one experience you had with a rude skateboarder, that is prejudice.

1.3.5.6 Biases

A person becomes biased when they settle on one explanation, idea, or truth and allow it to persist even as new evidence becomes available. A bias may develop through experience or reasoning that once seemed to support it, but has since been forgotten or discarded.

1.3.5.7 Fears

Knowing what your audience fears can guide your use of pathos and logos. You might find that unspoken fears cause your audience to be reluctant to concede to your argument regardless of how logical it seems. Fears are not always logical, but if you are aware of what your audience fears you can reassure them that your product or idea will help them avoid those things. The health and beauty industry, for instance, uses its audience’s fears of not being liked, wanted, manly, or desirable to convince them to buy all sorts of gadgets, powders, pills, creams, and other products all the time.

1.3.5.8 Behavior

Everything on the list above drives human behavior, and behavior is, in the end, the target of most rhetorical endeavors. Changing opinions, beliefs, and attitudes ultimately has implications for behavior, whether that behavior be casting a ballot or not casting a ballot, buying a Buzz Cola or not buying a Buzz Cola, or implementing a program to end racial profiling by the City Police force. Not only is it important to know what behavior you are hoping for, but it is also important to know the behaviors your audience already has. Even more importantly, as you construct your argument, you must know whether your audience’s behavior even lines up with their current opinions and attitudes. Often it does not, and when that is the case your argumentative task is different. Rather than changing opinions, you may only need to convince the audience to act on the opinions they already hold. You need to know not only what your audience thinks, but also how they act in order to choose the right reasons.

You might sum up all of the above in the two questions routinely asked by Lucifer and his twin brother in the Netflix series Lucifer:

- What does your audience fear?

- What does your audience desire?

Once you have figured out the beliefs, values, and opinions of your audience, you can choose effective reasons. Consider the following reasons to drink Buzz Cola. See if you can figure out which one worked for Abe Simpson, an 83-year-old resident of Springfield:

You should drink Buzz Cola because:

- Britney Spears likes it

- It has twice the sugar, and twice the caffeine of other colas.

- It will put the boogie back in your body.

- It will help you pull all-nighters when writing papers for English Class

Abe’s Answer: 3

1.3.6 Memory

Your audience will also determine 1) the types of sources you use, and 2) the origin of the sources you use. An academic audience will be looking for scholarly articles, books, and empirical evidence, while a popular audience will be looking for fewer and easier to read sources like other popular magazine articles, interviews, and perhaps blog posts. In regard to the origin of the sources, they should be located somewhere in the network of the discourse community you are speaking in and to.

1.3.7 Delivery

The format of the paper should reflect the needs of the audience. If your audience belongs to the Education, Psychology, Health, or Sciences discourse community, you should choose APA format. If your audience belongs to the Humanities discourse community, you should use MLA formatting. If your audience belongs to the Business, History, or Fine Arts discourse community, then you should use Chicago format. You will notice that the formatting and documentation styles reflect the values of the disciplines that use them.

1.3.8 Use of Persuasive Appeals

Your audience will also determine how you combine the persuasive appeals most effectively. A scholarly audience will respond more positively to ethos and logos, with kairos and pathos taking secondary roles.

1.4 Audience Analysis

While audience analysis does not guarantee against errors in judgment, it will help you make good choices in topic, language, style of presentation, and other aspects of your speech. The more you know about your audience, the better you can serve their interests and needs. There are certainly limits to what we can learn through information collection, and we need to acknowledge that before making assumptions, but knowing how to gather and use information through audience analysis is an essential skill for successful speakers.

1.4.1 Demographic Analysis

As indicated earlier, demographic information includes factors such as gender, age range, marital status, race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Whatever method you use to gather demographics, exercise respect from the outset. For instance, if you are collecting information about whether audience members have ever been divorced, be aware that not everyone will want to answer your questions. You can’t require them to do so, and you may not make assumptions about their reluctance to discuss the topic. You must allow them their privacy.

1.4.1.1 Age

There are certain things you can learn about an audience based on age. For instance, if your audience members are first-year college students, you can assume that they have grown up in the post-9/11 era and have limited memory of what life was like before the “war on terror.” If your audience includes people in their forties and fifties, it is likely they remember a time when people feared they would contract the AIDS virus from shaking hands or using a public restroom. People who are in their sixties today came of age during the 1960s, the era of the Vietnam War and a time of social confrontation and experimentation. They also have frames of reference that contribute to the way they think, but it may not be easy to predict which side of the issues they support

1.4.1.2 Gender

Gender can define human experience. Clearly, most women have had a different cultural experience from that of men within the same culture. Some women have found themselves excluded from certain careers. Some men have found themselves blamed for the limitations imposed on women. Relationship status can also inform and influence gender experience. While marriage can create a sense of social and financial security, it can also impose additional roles on both men and women. Divorce is even more demanding, especially if there are children in the mix. Even if your audience consists of young adults who have not yet made occupational or marital commitments, they are still aware that gender and the choices they make about issues such as careers and relationships will influence their experience as adults.

1.4.1.3 Race and Ethnicity

Now that it is generally accepted that race is an artificial construct, lots of people want to forget about it and become colorblind. At the risk of oversimplifying, this is the fundamental opposition in the conflict between the statements “all lives matter” and “black lives matter.” The proponents of the idea that all lives matter hope that the world can erase the lines between races, while the proponents of the idea that black lives matter hope to remind the world that, for now anyway, race matters. Because this game has been played unfairly for so long on the basis of racial stereotyping and the resulting oppression, people of color have radically different experiences and limited access to the privileges others take for granted. This makes race just as important as gender and other demographic information when considering an audience. Advertisers and political strategists haven’t forgotten it, and neither should rhetoricians.

1.4.1.4 Culture

In past generations, Americans often used the metaphor of a “melting pot” to symbolize the assimilation of immigrants from various countries and cultures into a unified, harmonious “American people.” Today, we are aware of the limitations in that metaphor, and have largely replaced it with a multiculturalist view that describes the American fabric as a “patchwork” or a “mosaic.” We know that people who immigrate do not abandon their cultures of origin in order to conform to a standard American identity. In fact, cultural continuity is now viewed as a healthy source of identity.

We also know that subcultures and cocultures exist within and alongside larger cultural groups. For example, while we are aware that Native American people do not all embrace the same values, beliefs, and customs as mainstream white Americans, we also know that members of the Navajo nation have different values, beliefs, and customs from those of members of the Sioux or the Seneca. We know that African American people in urban centers like Detroit and Boston do not share the same cultural experiences as those living in rural Mississippi. Similarly, white Americans in San Francisco may be culturally rooted in the narrative of distant ancestors from Scotland, Italy, or Sweden or in the experience of having emigrated much more recently from Australia, Croatia, or Poland.

Not all cultural membership is visibly obvious. For example, people in German American and Italian American families have widely different sets of values and practices, yet others may not be able to differentiate members of these groups. Differences are what make each group interesting and are important sources of knowledge, perspectives, and creativity.

1.4.1.5 Religion

There is wide variability in religion as well. The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found in a nationwide survey that 84 percent of Americans identify with at least one of a dozen major religions, including Christianity, Judaism, Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, and others. Within Christianity alone, there are half a dozen categories including Roman Catholic, Mormon, Jehovah’s Witness, Orthodox (Greek and Russian), and a variety of Protestant denominations. Another 6 percent said they were unaffiliated but religious, meaning that only one American in ten is atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular” (Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, 2008).

Even within a given denomination, a great deal of diversity can be found. For instance, among Roman Catholics alone, there are devoutly religious people who self-identify as Catholic but do not attend mass or engage in other religious practices, and others who faithfully make confession and attend mass but who openly question Papal doctrine on various issues. Catholicism among immigrants from the Caribbean and Brazil is often blended with indigenous religion or with religion imported from the west coast of Africa. This blending is vastly different from Catholicism in the Vatican.

The dimensions of diversity in the religion demographic are almost endless, and they are not limited by denomination. Imagine conducting an audience analysis of people belonging to an individual congregation rather than a denomination: even there, you will most likely find a multitude of variations that involve how one was brought up, adoption of a faith system as an adult, how strictly one observes religious practices, and so on.

Yet, even with these multiple facets, religion is still a meaningful demographic lens. It can be an indicator of probable patterns in family relationships, family size, and moral attitudes.

1.4.1.6 Group Membership

In your classroom audience alone, there will be students from a variety of academic majors. Every major has its own set of values, goals, principles, and codes of ethics. A political science student preparing for law school might seem to have little in common with a student of music therapy, for instance. In addition, there are other group memberships that influence how audience members understand the world. Fraternities and sororities, sports teams, campus organizations, political parties, volunteerism, and cultural communities all provide people with ways of understanding the world as it is and as we think it should be.

Because public speaking audiences are very often members of one group or another, group membership is a useful and often easy to access facet of audience analysis. The more you know about the associations of your audience members, the better prepared you will be to tailor your speech to their interests, expectations, and needs.

1.4.1.7 Education

Education is expensive, and people pursue education for many reasons. Some people seek to become educated in a university setting, while others seek to earn professional credentials. Both are important motivations. If you know the education levels attained by members of your audience, you might not know their motivations, but you will know to what extent they could somehow afford the money for an education, afford the time to get an education, and survive educational demands successfully.

The kind of education is also important. For instance, an airplane mechanic undergoes a very different kind of education and training from that of an accountant or a software engineer. This means that not only the attained level of education but also the particular field is important in your understanding of your audience.

1.4.1.8 Occupation

Often people choose occupations for reasons based in motivation and interest, but their occupations also influence their perceptions and their interests. Most occupations encounter numerous misconceptions. Many people believe that teachers work an eight-hour day and have summers off. However, when you ask teachers about this, ,you might be surprised to find out that they take work home with them for evenings and weekends. Duringthe summer, they may teach summer school as well as taking courses in order to keep up with new developments in their fields and for recertifications.. Without knowing the truth about teachers and time off, you would still know that teachers have had rigorous generalized and specialized qualifying education because they have to go to college and pass exams to enter the profession. You would also know, that they have a complex set of responsibilities in the classroom and the institution. Further, you would understand that, to some extent, they have chosen a relatively low-paying occupation over such fields as law, advertising, media, fine and performing arts, or medicine.

If your audience includes doctors and nurses, you know that you are addressing people with differing but important philosophies of health and illness. Learning about those occupational realities is important in avoiding wrong assumptions and stereotypes. Do not assume that nurses are merely doctors “lite.” Their skills, concerns, and responsibilities are almost entirely different, and both are crucially necessary to effective health care.

1.4.1.9 Dialect

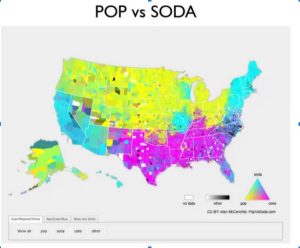

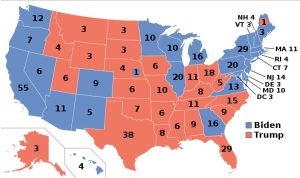

Dialect is an important marker of identities, and in addition to having implications for word choice and sentence construction, it often correlates with other demographic and psychographic data to give you a clearer picture of your audience. For example, imagine that you are arguing that Weld County School District 6 should spend more money on music programs, but the only information you have on the School Board is that 6 out of 7 of them refer to a carbonated beverage as either “pop” or “coke,” and only one of them refers to a carbonated beverage as a “soda.” After comparing the maps below, what can you infer about the political views of the school board?

The first thing you may notice is that the middle and southern states use “pop” and “coke,” with a few isolated pockets of people who say “soda,” usually in metropolitan areas. After looking at the second map, you may notice that with some exceptions, the states who gave their electoral votes to the Republican candidate mostly say “pop” or “coke,” while the states who gave their electoral votes to the Democratic candidate. If you were to zoom in on Weld County on both maps, you would see the same correlation: the county has a lot of people who say “pop” and a lot of people who voted for the Republican Candidate. The generalization could be made, then, that people who ask for a “pop” when they want a carbonated beverage are more likely to have conservative political views.

If this holds true for the members of the school board, and you know that political conservatives are hesitant to raise taxes, you might want to avoid arguing that taxes should be raised to pay for more music programs, and suggest other methods of raising the funds.

Now, qualitative data from individuals who know the members of the school board suggests that this generalization might not be completely accurate, so it is important to balance it with both other demographic data as well as more qualitative psychographic data, if available.

1.5 Psychographic Analysis

Psychographic information includes such things as values, opinions, attitudes, and beliefs. Authors Grice and Skinner present a model in which values are the basis for beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors. Values are the foundation of their pyramid model. They say, “A value expresses a judgment of what is desirable and undesirable, right and wrong, or good and evil. Values are usually stated in the form of a word or phrase. For example, most of us probably share the values of equality, freedom, honesty, fairness, justice, good health, and family. These values compose the principles or standards we use to judge and develop our beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.”[2]

It is important to recognize that, while demographic information is fairly straightforward and verifiable, psychographic information is much less clear-cut. Two different people who both say they believe in equal educational opportunity may have very different interpretations of what “equal opportunity” means. People who say they don’t buy junk food may have very different standards for what specific kinds of foods are considered “junk food.”

Furthermore, people inherit some values from their family upbringing, cultural influences, and life experiences. The extent to which someone values family loyalty and obedience to parents, thrift, humility, and work may be determined by these influences more than by individual choice.

Psychographic analysis can reveal preexisting notions that limit your audience’s frame of reference. By knowing about such notions ahead of time, you can address them in your essay. Audiences are likely to have two basic kinds of preexisting notions: those about the topic and those about the writer.

Licenses

The sections “Demographic Analysis” and “Psychographic Analysis” contain derivative material from “Preparing for Public Speaking: Audience Analysis” at https://experientiallearningininstructionaldesignandtechnology.pressbooks.com/chapter/8-1-audience-analysis/ from Experiential Learning in Instructional Design and Technology by Joshua Hill and Linda Jordan and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, used under CC BY. “Both sections are licensed under CC BY by Ty Cronkhite.

The image “Map of Pop vs. Soda usage in the U.S.” is located at www.PopVsSoda.com and is licensed under CC BY by Alan McConche.

The image “Final Electoral Results for 2020 Presidential Election” is located at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_United_States_presidential_election and has been released to the public domain.

A person who has something to lose or gain in the outcome of a particular discussion.